Al-Muʿiz Lidīn Allāh al-Fāṭimiy Street Development Project (The Outdoor Museum)

Cairo is recognized as having one of the most distinctive urban experiences in the world. Throughout the city, the streets and buildings are architectural masterpieces, representing various periods of the city’s history. Unfortunately, the very heritage of the city is now threatened by encroachments, demolition, and theft.

Historic Cairo was added to the World Heritage List in 1979, in recognition of its historical, archaeological, and architectural significance. In 1980, a UNESCO consultant undertook one of the earliest studies of Historic Cairo to define a strategy to preserve the historic city. In the same year, a development project in the Darb Qirmiz Quarter of Historic Cairo was implemented by the Egyptian Antiquities Organization and German Archaeological Institute, winning the 1983 Aga Khan award for Architecture.

In 1997 the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA), conducted a rigorous study to define a coherent urban conservation strategy within Historic Cairo. The UNDP proposed urban policies that would ensure the meaningful implementation of development and rehabilitation as well as comprehensive conservation strategies, and the UNDP report was used as the primary reference for the “National Project for Historic Cairo” (NPHC). The NPHC project included the “Development of al-Muʿiz Street,” which was subsequently implemented by the Ministry of Culture.

In 2002, the Ministry of Culture and the World Heritage Center organized an international urban conservation conference to preserve the Islamic monuments of Cairo. The conference made several recommendations related to the historical city, including the recommendation to strengthen and support the institutional framework and coordination mechanisms among various stakeholders in Historic Cairo. Professionals at the conference also stressed the need to prepare a comprehensive urban plan to preserve and develop the historic city, as well as to improve the conditions of the infrastructure networks, the decay of which is a significant cause of the deterioration of the historic city (UNESCO, 2012).

List of the monuments on al-Muʾiz Street1

-

Bāb al-Futūḥ: Fatimid Era, 1087 AD, built by Badr al-Dīn al-Jamālī

-

al-Ḥākim Bi ʾAmr Allāh Mosque: Fatimid Era, 990-1013 AD, was started by al-ʿAzīz Bi Allāh and completed by his son, al-Ḥākim Bi ʾAmr Allāh.

-

Zāwiyat Sīdī Abū al-Khair al-Kulaibātī: Circassian Mamlūks Era, 1503 AD, built by Judge Sharaf al-Dīn Mūsā Bin ʿAbd al-Ghaffār

-

Mosque, Sabīl, and Kuttāb of Sulaimān Āghā al-Salaḥdār: Muḥammad Alī Bāshā Era, 1837-1839 AD, built by Sulaimān Āghā al-Salaḥdār Bik

-

Waqf of Muṣṭafā Jaʿfar al-Salaḥdār: Ottoman Era, 1713 AD, built by Muṣṭafā Jaʿfar al-Salaḥdār

-

al-Aqmar Mosque: Fatimid Era, 1125 AD, built by the Caliph al-Āmir bi Aḥkām Allāh Abu Alī al-Manṣūr bin Al-Mustaʿlā bi Allāh

-

Sabīl and Kuttāb of ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Katkhudā: Ottoman Era, 1744 AD, built by the prince ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Katkhudā

-

Palace of al-Amīr Bishtāk: Bahriyya Mamlūks Era, 1334-1339 AD, built by al-Amīr Sifāldīn Bishtāk al-Nāṣirī

-

Ḥammām of Sultan al-Ashraf Īnāl: Circassians Mamlūk Era, 1456 AD, built by Sultan Īnāl bin ʿAbd Allāh al-ʿAlāʾiy

-

al-Kāmiliyyah School: Ayyubid Era, 1225 AD, built by Sultan al-Kāmil Nāsir al-Dīn Muḥammad Bin al-Malik al-ʿĀdil Abī Bakr al-Ayyūbī. During the Ottoman Era, al-Amīr Hasan Katkhudā al-Shaʿrāwī Zāwiyat for praying at the area that was occupied by Eastern Īwān.

-

School of Sultan Barqūq: Circassians Mamlūk Era, 1384-1386 AD, built by Sultan Barqūq

-

Sabīl Muḥammad Alī Bāshā at al-Naḥḥāsīn: Muḥammad Alī Bāshā Era, 1828 AD, built as a charity in memory of his son Ismāʿīl Bāshā

-

School and Bimaristān Sultan al-Manṣūr Qulāwūn: Mamlūk Era, 1284 AD, built by Sultan al-Manṣūr Qulāwūn

-

Kuttāb of al-Nāṣir Muḥammad bin Qulāwūn: Bahriyya Mamlūks Era, 1295-1303 AD, built by al-Nāṣir Muḥammad bin Qulāwūn

-

al- Ẓāhir Bībars al-Bindiqdārī School: Bahriyya Mamlūks, 1262 AD, built by Sultan al-Ẓāhir Bībars al-Bindiqdārī

-

Khasrū Bāshā Sabīl and Kuttāb: Ottoman Era, 1535 AD, built by Khasrū Bāshā

-

al-Sāliḥiyya School: Ayyubid period, 1243-1249 AD, built by King al-Sāliḥ Najm al-Dīn Ayyūb to teach the four Islamic books of thought. Shajarat al-Durr, his wife, later added a shrine to it.

-

Mosque of al-Sheīkh Muṭṭahar: Ottoman era, 1744 AD, built by al-Amīr ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Katkhudā

-

Sultan al-Ashraf Barasbāy al-Ẓāhirī School: Circassians Mamlūk Era, 1425 AD, built by Sultan al-Ashraf Barasbāi al-Ẓāhirī

-

Sabīl, Book, Dome, and House of al-Ghūrī: Circassians Mamlūk Era, 1503 AD, built by Sultan Qānṣūh al-Ghūrī

-

Sultan al-Ghūrī Mosque: Circassians Mamlūk Era, 1504-1505 AD, built by Sultan Qānṣūh al-Ghūrī

-

Saqīfat al-Ghūrī: Muḥammad Alī Bāshā Era, the nineteenth century, named after al-Ghūrī since it was close to al-Ghūrī Mosque

-

al-Fākahānī (al-Jāmʿ al-Afakhar) Mosque: Fatimid Era, 1148 AD, built by the Caliph al-Ẓāfir Bi ʾAmr Allāh. Aḥmad Katkhudā al-Kharbuṭlī then renovated it during the Ottoman Era, adding a Sabīl and a Kuttāb. He also built a fruit trading agency next to it.

-

Sabīl Muḥammad Alī Bāshā in al-ʿAqādīn: Muḥammad Alī Bāshā Era, 1820 AD, built by him as a charity in memory of his son al-Amīr Ṭūsūn

-

al-Sukkariyyah Ḥammām: Ottoman Empire, the eighteenth century, built by Judge al-Fāḍil ʿAbd al-Raḥīm Bin Alī al-Bīsānī

-

Nafīsah Al-Baīḍā Agency Façade: Ottoman Era, 1796 AD, built by Nafīsah Khātūn

-

Sabīl of Nafīsah Al-Baīḍā: Ottoman Era, 1796 AD, built by Nafīsah Khātūn

-

Sultan al-Muʾayyad Sheīkh Mosque: Circassians Mamlūk Era, 1415-1420 AD, built by al-Muʾayyad Sheīkh al-Maḥmūdī

-

Bāb Zūaylah: Fatimid Era, 1092 AD, built by Badr al-Dīn al-Jamālī

-

North Cairo Wall: Fatimid Era, 1087 AD, built by Badr al-Dīn al-Jamālī

The condition of al-Muʿiz Street before the project2

The Commercial Activities: The design patterns of the buildings and historic retail shops, as well as the commercial activity illustrate the historical importance of al-Muʿiz Street. Street vendors sit in front of these historic buildings, offering their goods. Roughly 630 shops operate between Bāb al-Futūḥ and Bāb Zūaylah with business activities ranging from onion and olive markets, coffee shop supplies, copper and stainless-steel utensils, goldsmiths, perfume, spice, clothing, fabrics, shoes, and furniture shops.

Historic Buildings: The Ministry of Awqaf has leased a large number of historic buildings for commercial activity. Many tenants of the historical buildings misused their leases, modifying the original design. As a result of the misuse of these buildings, many were closed, no longer periodically inspected, and began to deteriorate. The SCA implemented restoration projects for many monuments to restore the damage caused by the 1992 earthquake. The Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development (AFESD) provided a grant for the development of the al-Darb al-Asfar neighborhood of al-Muʿiz Street, dedicated to the restoration of three historic buildings: Baīt al-Saḥīmy, Baīt al-Kharazātī, and Baīt Muṣṭafā Jaʿfar.

Infrastructure: Massive neglect in the area caused the sewage system in the area to deteriorate, which led to leakage and sewage overflow in the streets. The excessive moisture leached the soils of their nutrients, filling facades with salts and deteriorating health equipment inside the building. This destruction put the safety of historic buildings at risk, forcing some residents to leave the area.

Street Level: In an attempt to refurbish the streets, the government oversaw the paving of the historic streets. However, these renovations were conducted without taking into account the historical value of the street, causing the basalt road to vanish and the street levels to rise. This led to uneven levels between streets, entrances, and buildings, and even caused some historic building facades to disappear.

Building Conditions: Over 50 percent of the existing buildings were in poor condition and required significant repairs and facade improvements.

Nature: The natural aesthetic and architectural integration of elements of al-Muʿiz Street and the historic city were adversely affected by shops that used contrasting advertising banner materials.

Traffic: The lack of traffic control in the streets adversely affected the streets and the health of the buildings. Large vans park in these busy streets, causing traffic jams and impeding movement in the streets.

The Cleanliness: Garbage buildup proved to be clear problem, as waste management facilities were insufficient. Waste built up everywhere in the streets and piles of garbage accumulated in the front entrances of the buildings.

Public Utilities: Public utilities represented less than 2 percent of the total street activities. In total there was a local administration office, two post offices, one medical clinic, and an ophthalmology hospital behind the Qalāwūn Group; however, the road lacked many of the services and public utilities necessary for its tourist and commercial nature, such as public restrooms and tourist information centers.

The development project

The UNDP study catalyzed the start of the NPHC, and in turn the Egyptian government showed great interest in the NPHC. In 1998, a “Center for Development Studies of Historic Cairo” (CDSHC) was established, which included an urban and architectural design unit as well as a documentation unit; the CDSHC was assigned to conduct the needed studies, supervise the work, and coordinate between the authorities. The CDSHC then developed a plan of action within the NPHC which included the rescue of historic buildings after the massive damage caused by the 1992 earthquake as well as the rehabilitation of the Historic Cairo area (UNESCO 2012).

The UNDP study presented proposals as part of the NPHC related to tourism development in al-Muʿiz Street. The proposal aimed to emphasize and protect the historic aspects of al-Muʿiz Street, which was taken over by Al-Azhar Street upon its establishment in 1845. The primary plan was to turn the street into a pedestrian-only road and establish a new pedestrian bridge across al-Azhar Street. The proposal also suggested redesigning the facades to suit the style of the historic street, providing signs and shaded places, and re-purposing certain landmark buildings to create new space for urban activities, all in an attempt to improve the area’s social and economic conditions.

800 million Egyptian Pounds were allocated to the three-part NPHC project: the restoration of almost-falling monuments, the conservation activities and the comprehensive urban development (including upgrading the infrastructure), and the reuse of the historic building.

The restoration projects were divided into four phases, aimed to restore 143 registered monuments. The first and second phases were aimed at the restoration of the monuments of al-Muʿiz Street. The first phase included the al-Ghūrī monuments, al-Muʾayyad Sheīkh Mosque, the Northern Wall, and Bāb al-Futūḥ, and the second phase included the Kuttāb and the Dome of Najm al-Dīn Ayyūb, Sabīl Kuttāb Khasrū Bāshā, al-Ẓāhir Bībars School, Bishtāk Palace, Īnāl ḥammām, al-Kāmil Mosque, Sultan Barqūq Mosque, the Dome of al-Nāṣer Qulaūūn, Muṭahar Mosque, and al-Ashraf Barasbāi School and Mosque. The restoration work of the monuments of al-Muʿiz Street ended in 2008.

The development of the northern part of al-Muʿiz Street was the first phase of comprehensive conservation and urban development; the total cost was 40 million Egyptian Pounds, divided between infrastructure upgrades, paving, and aesthetic improvement. Since the project was interrupted several times, the first phase took eight years to be completed. The project started in 2002 and ended upon completion in February 2010. The second phase of urban conservation works included the completion of al-Muʿiz Street from Al-Azhar Street to Bāb Zūaylah, as well as Al-Jamālīya Street parallel to Bāb al-Naṣr and al-Mashahad al-Ḥusaini. The head of the NPHC, Professor Mohamed Abdel Aziz, said in an interview that the project was halted between 2007 and 2011 due to administrative problems; the project, however, was resumed in 2012.

Project implementation

Commercial Activities: Certain activities were identified as inappropriate for the nature of the street, then, alternative places were allocated to them or owners were encouraged to switch businesses. For example, those who sold onions, lemons and olives were relocated, from the al-Ḥākim Mosque to the Sūq al-ʿBūr, workshops and copper artisans were encouraged to switch businesses.

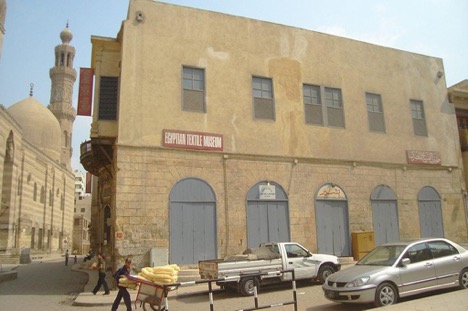

Historical buildings: The restoration works of al-Muʿiz Street were completed during the first and second phases of the restoration of the Historic Cairo monuments. The concept of reuse was applied at Sabīl and Kuttāb Muḥammad Alī Bāshā at al-Naḥḥāsīn by converting it to an Egyptian Textile Museum for the total cost of 12 million pounds.

Sabīl Muḥammad Alī Bāshā at al-Naḥḥāsīn after its conversion to the Egyptian Textile Museum (Source: Tadamun)

Infrastructure: The project included replacing the decrepit networks. For example, water, sanitation, and electricity networks were renovated and rain drainage networks were added to the street. Gas pipes were further added to mitigate the need to re-dig and install future pipes.

Street Leveling: The street was leveled back to the standards of the 1920s with remnants of black basalt found at a depth of about 70 cm below the pre-commencement level. Granite blocks were used to pave the street, pavements, and bridges and the original basalt was used to pave some side alleyways.

Buildings Condition and the General Nature: Modifications have been made to the facades of some buildings through adding wooden elements, repainting the premises, and restoring doors, windows, whites, and cracks. Additionally, shops signs were remodeled and night lighting was added to the street.

Traffic: Only bicycles and motorcycles were allowed to enter the street during the day, as well as police cars, fire trucks, and ambulances. Electronic gates were inserted at both ends of the street to regulate cars and prevent them from entering during the day.

Hygiene and public facilities: Two public toilet units were added, in addition to the allocation of a private cleaning company responsible for collecting garbage and cleaning the street periodically.

Project funding

The NPHC project was primarily funded at the beginning by its allocated budget of 800 million Egyptian pounds. By the opening of al-Muʿiz Street in February 2010, LE 250 million had already been spent on renovations as well as building and developing the infrastructure, after the separation of the SCA from the Ministry of Culture.

The NPHC received a diverse array of sources for funding. From the government, they received financial support from the Ministry of Tourism, Housing and Awqaf. The Ministry of State for Antiquities received two grants totaling LE 9 Million from the Ministry of International cooperation to assist in completing the second phase. The political turmoil and economic crises led to a reduction in allocated funding to assist in the completion of the project. Various entities including the Kuwait Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development, the Aga Khan Foundation, the European Union, the American Fund, American Research Center, and the Ministry of State for Antiquities are also working to increase its resources. The NPHC is currently conducting feasibility studies to convert some of Cairo’s historic shops into heritage hotels, where traditional crafts bazaars are opened at the ground floor while rooms are placed on the upper floors.

Opportunities and constraints

Historic Cairo has several remarkable elements of attraction, including an urban texture that can be seen in its narrow streets as well as huge mosques and high minarets in the background. Al-Muʿiz Street, in turn, represents this concept in full. It is a street with small alleyways branching out of it. At its northern end is the minaret of al-Ḥākim Mosque, and at its southern end the minaret of al-Muʾayyad Sheīkh Mosque. All of that gives the street huge potential. In 1998, the French Egyptologist Veronica Cedro and her partner Youssef Takla decided to invest in Egypt by buying an existing residential building at al-Muʿiz Street from its residents, turning it into a boutique hotel with a design that reflects the history of the area. Its occupancy rates have been excellent since its opening, despite political turmoil and poor tourism.

Adding Historic Cairo to the World Heritage List is also an opportunity to benefit from the studies and recommendations made by UNESCO and UNDP.

Nevertheless, several obstacles face the NPHC. The area of Historic Cairo alone includes 313 registered monuments. Although the SCA is responsible for all the historic buildings, it owns less than 5% of them. The remaining 95% of the buildings are owned by the Ministry of Awqaf. Occasionally, this causes roadblocks for the project as a result of overlapping multiple actors in the decision-making process (UNDP and Supreme Council of Antiquities, 1997).

In terms of funding, the annual cost of restoration and maintenance of Islamic and Coptic monuments before the 1992 earthquake was about $2.4 million (8 million Egyptian pounds). It increased to 30 million pounds after the earthquake. As a result of inflation, it reached approximately 48 million Egyptian pounds by 1996. Currently, after the liberalization of the exchange rate, it is expected that the cost of some of the remaining projects will double from LE 450 million to more than LE 800 million. In addition to limited financial resources, the SCA’s experience in intricate restoration work is also limited; therefore, much of the restoration and maintenance work has been assigned to the private sector under the supervision of the SCA, which in turn led to varied final results in terms of standards and quality.

Outcome and impact

Upgrading the Infrastructure:

The replacement and renovation of the area’s infrastructure positively impacted residents, visitors, and shop owners. Many of the residents who had previously left the area decided to return thanks to the improvement of facilities, sewage systems, and the enhanced commercial and tourist climate of the street. Despite these improvements and the implementation of gas networks in 2009, the area has not yet been supplied with natural gas.

Status of Residential Buildings:

The small lanes and alleyways of al-Muʿiz Street did not receive the same attention as the main street. Many buildings are still poorly constructed, despite the occasional development of facades.

Rental Value:

The majority of the inhabitants of the area have been living there for approximately 25-50 years, and a large percentage of their housings are old leases. Before the project, the rental value ranged between 10-150 pounds; after the completion of the project; however, it rose to about 500 pounds.

Tourism and Commercial Activity:

Closing the street to cars during the day has had a positive impact. It gave pedestrians, tourists, and those wishing to navigate between al-Muʿiz Street’s monuments and shops greater freedom, causing an improvement in tourism as well as an increase in inbound tourism.

Traditional Crafts:

The majority of the workshops and crafts shops were transformed into bazaars and coffee shop supplies, beginning to move away from traditional handicrafts.

Automatic Movement Control:

Limiting the movement of cars in the street has led to a decrease in pollution and disturbance. It also helped to protect historic buildings from the threat of ground vibrations and car emissions.

Community Participation:

Community member’s voices were continually disregarded even though meetings were held between the neighborhood and the Ministry of State for Antiquities. These meetings were designed to increase transparency between the two groups. However, when residents of the area would express their opinions on the design proposals, their opinions were not considered. The residents and shop owners were not involved in the implementation of the project.

The Reuse:

The restoration of the historic monument of al-Muʿiz Street and the idea of the reuse led to the formation of several attempts to organize events, exhibitions, and cultural activities. One of those attempts was the Taṣmīm +20 Exhibition formed in June 2010 in Baīt al-Saḥīmy, Baīt Muṣṭafā Jaʿfar, and Sabīl al-Salaḥdār.

Sustainability

Social/Economic Sustainability

During the 1984 conference held in Cairo to discuss the urban growth of the city, the Aga Khan decided to give Cairo residents a park in the heart of the historic high-density city. While the site was being selected, and the project was under study, the implementation was delayed until the early 1990s due to the archaeological discovery of the historic Ayyubid Wall. In addition, the establishment of the Aga Khan Program to Support the Historic Cities caused the Aga Khan Foundation to re-think its concept on the park. The foundation believed that establishing the park and restoring the historic wall would serve as a catalyst for the physical rehabilitation of the neighboring areas of al-Darb al-Aḥmar. They also believed that a series of community-based projects would contribute to improve living conditions and provide cultural, social, economic and institutional support to the residents. In comparing the outcome of this project versus the development of al-Muʿiz Street Project, the latter may appear to be better in terms of look of the street, the shape of the facades of buildings and shops, and the lighting of historic buildings. However, the effect of the al-Darb al-Aḥmar Development Project on the local community far outweighs the effect of the al-Muʿiz Street Project. Not only did the al-Darb al-Aḥmar Development Project aim to maintain and increase the material efficiency of historical buildings, it also aimed to link physical interventions with social and economic development through the provision of microcredit, vocational and professional training, community participation and the creation of new job opportunities to maximize the financial impact. The mainstay of this strategy was the establishment of the “al-Darb al-Aḥmar Community Development Company,” a local association that acts as a tool to ensure sustainable development and continues participation for all stakeholders in the area (UNESCO 2012).

During the development project, the local community of al-Muʿiz Street did not receive such support to achieve sustainable socio-economic development as the al-Darb al-Ahmar project. Although Historic Cairo is one of the most traditional handicraft areas, the development strategy of the al-Muʿiz Street Project was not aimed at preserving these crafts and industries. It appeared that the project did the opposite, as many of these workshops have switched businesses to bazaars, gift shops, and coffee shop supplies, among others, at the encouragement of the project planners. The al-Muʿiz Street Project also moved the market of onions, lemons, and olives from the front of the al-Ḥākim Mosque to the Sūq al-ʿAbūr. Nevertheless, there are still some street vendors because the area has a wide reputation with tourists and locals alike.

After the opening of the project in February 2010, there was a boom in the rates of foreign and domestic tourism in the area. This short-lasting boom led to a tangible improvement in the incomes of shop owners, especially those who switched businesses into tourism products. A period of stagnation in sales started in January 2011 due to low rates of tourism coupled with the continuous increase in prices; this slowdown led to an unstable local economy.

Institutional Sustainability

Since its inception, many entities have been involved in the NPHC. Though there were various stakeholders involved, the Ministry of Culture was in charge of development projects and the restoration the historic monuments. It’s worth noting that 95 percent of the historic buildings were owned by the Ministry of Awqaf. After the January 25th, 2011 uprising, a decision was made to separate the SCA from the Ministry of Culture, turning SCA into an independent entity, the Ministry of State for Antiquities. Since that decision did not resolve the technical and financial overlaps between both ministries, the Ministry of State for Antiquities still oversees the NPHC.

After the completion of the project in 2010, a cleaning company was contracted to clean al-Muʿiz Street, which may have helped to maintain the cleanliness of the street; however, it is impossible to separate the street from the surrounding areas. The task of this company was to remove garbage outside the street without a comprehensive vision or coordination between this company and the municipality responsible for collecting waste from the other streets. Locations for garbage collection at the entrances of the street were not identified, nor were plans made detailing how to transfer the garbage from the cleaning company to the municipality in a sustainable manner.

In spite of the enormous spending on the project and the replacement of infrastructure networks, the blockage of the main water pipe in Al-Azhar Street on February 10, 2012 led to the flooding of al-Muʿiz Street with wastewater due to its low level compared with the surrounding streets. The Ministry of State for Antiquities informed the Sewerage Authority, which treated the blockage of the main pipe in Al-Azhar Street and then pumped water out of al-Muʿiz Street. The cleaning company then disinfected al-Muʿiz Street and cleaned it due to the unpleasant smell caused by sewage water. Although the problem of sanitation on al-Muʿiz Street was a tragedy for the residents and shop owners, many years before the development project, there is still no sustainable institutional system that protects the area from facing such an incident again. The development process should be accompanied by a strategy for coordination between the Ministry, the neighborhood, and the Sewerage Authority to carry out clearance and maintenance of the main pipes in the area and the drainage holes on the street periodically to ensure the safety of the area and to prevent a similar incident from arising.

In March of 2013, the Ministry of State for Antiquities announced a tender for the project “Raising the efficiency of al-Muʿiz Street” to upgrade the street and restore it to its original appearance. The project included the supply, installation, and repair of electrical barriers that prevent the entry of cars in addition to electrical maintenance. To maintain the lighting units in the area, repair the damaged ones, and re-install what has been stolen, the Egyptian Company for Audio and Lights was contracted. This meant re-spending money on projects that had already been completed, thus calling for a review of the institutional system responsible for the management, operation, and maintenance of NPHC at all stages.

Tadamun’s Vision

The development of al-Muʿiz Street is considered one of the essential experiences of Egypt in the field of urban conservation. The project went beyond the idea of just preserving the monuments to improve the area in full by also considering the preservation of the urban fabric. Yet this project could have achieved a more significant outcome if all aspects of the conservation plans of cities and areas had been taken into account.3 Some important points to consider when designing and implementing a project are listed below:

-

The purpose of the urban development projects in the historic areas is not only to achieve the physical development of buildings and facades, especially with the presence of forms of crafts and traditional industries that represent the historical heritage of the area. It is necessary to work through an integrated approach to preserve and develop these industries to ensure their continuity, improve their quality, and increase their competitiveness in local and global markets for sustainable economic/social development capable of improving the population’s living conditions. The work should be done in partnership with community institutions and local entities representing the residents of the area. Even though the project has succeeded in improving the urban environment, it neglected the socioeconomic development of the residents of the area.

-

There is a clear overlap in the mandates of the entities involved in the project (Awqaf, Antiques, Governance, neighborhood, utilities, urban coordination, and others), yet each body handles any project’s crisis separately without a comprehensive view. There must be an integrated vision and mechanisms for management and maintenance through an institutional framework. The solution is not to create new or alternative entities (such as contracting a cleaning company to clean only on al-Muʿiz Street), but instead coordinating the efforts of the government entities, and cease treating the area as an isolated part of the city. Investment to support and build the capacity of the authority responsible for maintaining the area should be made, as well as coordinating between the stakeholders regarding the infrastructure in the street and surrounding areas. All necessary measures should be taken to prevent the recurrence of such crises, and to develop a clear strategy for periodic maintenance to reduce re-spending on things have already been established, but then deteriorated as a result of a lack of follow-up.

-

The al-Muʿiz development project did not take into account the historical study of materials used in pavement and facades in terms of content, design, or dimensions. For example, the original road was built using black basalt slabs, and the dimensions of the original tiles were 10 × 20 cm. The paving, however, was made of granite slabs of different dimensions from the original design. Following the implementation of the project, the original basalt slabs were discovered under the repeated paving layers. These historic slabs were reused in paving some surrounding alleys, which gives incorrect future indications about the history of these streets, their design, and materials used. Moreover, in the development of the facades of the buildings, wooden elements have been added with a design similar to the historic Islamic nature, but it has no historical significance for the successive prosperous periods the street has faced.

-

There is still no detailed study on the reuse of unused historic buildings, many of which have already been dedicated to cultural activities. In a previous experiment in the al-Darb al-Aḥmar district, the Aga Khan Foundation has re-used the Darb Shaghlān Historical School as a library to serve the people of the al-Darb al-Aḥmar area by providing books, training for children, and free periodic medical check-ups and awareness seminars. This initiative improved the social and cultural climate in the area, offering a clear and positive impact on children and adults. The study of unused historic buildings and the development of ideas for their reuse is vital when considering the needs of the surrounding community, while studying the design of the buildings. In addition to the transformation of historic and heritage buildings into cultural centers, the local community should be considered more carefully, taking into account its direct needs in terms of public services and spaces, as well as the balance between tourism and community services.

-

The security approach dominates the development of historic areas in Egypt. This approach is reflected in several previous proposals, such as the creation of electronic gates on the borders of the street, the intensification of security around the area, the limitation of uses to specific activities, the removal of street vendors and others without regard for the urban nature of the area and the daily life of its residents. Yet despite all of these attempts, these measures did not prevent theft or encroachment within the area.

-

In the wake of poor economic conditions, there are concerns surrounding the completion of the project’s future phases. Successful development projects within the historic city are therefore a critical factor in increasing resources, as they help to build confidence in the feasibility of the work being carried out, leading to the flow of financial aid. We must prepare by developing plans and future studies to determine the different types of partnerships, both public and private, as well as the willingness of the people of the area to contribute to the development work as before in the project to develop the community of al-Darb al-Aḥmar, whether material contributions, effort, or the provision of raw materials.

Finally, these experiences of urban conservation, such as the experience of al-Muʿiz Street, the complex of religions in ancient Egypt, and the experience of the Aga Khan Cultural Foundation in al-Darb al-Aḥmar should be commended as experiments and models. They deserve follow-up as development projects and evaluation to help those working in the future to avoid making the same mistakes when applying conservation concepts to new development projects.

References:

Jim Antoniou, Stefano A. Bianca, Sherif Mahmoud El-Hakim, Ronald Lewcock, and Michael Welbank. 1980. “Conservation of the Old City of Cairo.” UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000044624

Hossam Aboulfotouh. “Rehabilitation of Historic Cairo Final Report,” in Framework Plan. (Cairo: United Nations Development Program and the Supreme Council for Antiquities, 1997,) https://www.academia.edu/10945362/Rehabilitation_of_Historic_Cairo_Final_Report_Chapter-6_on_Framework_Plan_UNDP_Cairo_1997

Franco Miglioli, Daniele Pini, Frederica Felisatti, Mariam el Korachy, Ahmed Mansour, and Ingy Waked. “Urban Rehabilitation Project for Historic Cairo, First Report of Activities.” UNESCO World Heritage Center. 2010. http://www.urhcproject.org/Content/studies/EN_ActionPlan.pdf

The Great Street al-Muʿiz Lidīn Allāh al-Fāṭimiy Street, Historic Cairo, Ministry of Culture Publications, Supreme Council of Antiquities.

“Newsletter of the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities,” Ministry of Antiquities 14 (July 2017): http://www.egyptologyforum.org/MOA/MoA_Newsletter_14_English.pdf

Cairo Governorate. 2008. “About the Historic Cairo Project” http://www.cairo.gov.eg/information/DocLib1/القاهرة%20التاريخية.pdf

1. The monument of Islamic Cairo, Center for Archaeological Studies and Research

2. Source of information in this section: Report of UNDP and Supreme Council of Antiquities (1997) and publications of the Ministry of Culture, Supreme Council of Antiquities

3. According to The Washington Charter: Charter on the Conservation of Historic Towns and Urban Areas (1987), historic areas, in addition to their role as landmark documents, embody the values of traditional urban cultures. The conservation plan must be preceded by the phases of interdisciplinary studies covering all areas of construction. To ensure the effectiveness of the urban conservation plan for historic cities, it must be integrated into harmonious economic, social and planning development policies.

Comments