“Land & Services” Policy: What We Need to Learn from the Experience of the al-Salām District in Ismāʿīlīya

With a tall minaret in its main square, surrounded by trees, the al-Salām district is located in the northern part of the city of Ismāʿīlīya. Around the mosque, movement is slow. A bean cart is located next to a local coffee shop. Across the street, some pick-up cars park and form a taxi stand. On the other side, there is a kiosk where an outlet sells products and meats of the army.

The al-Salām district is a systematically-planned neighborhood inhabited by middle-class people with all the necessary utilities, services, and infrastructure. The district’s main square houses the al-Salām Mosque and many trees—a site we are hardly able to see in many districts inhabited by low-income groups. Thirty-eight years ago, however, this was not the case, as the area was considered to be an “informal area” by specialists; an informal area is one that lacks all formal services, facilities, and planning. Nevertheless, in 1978, the al-Salām district witnessed its first urban development project, using the “Land & and Services” approach, which led to the improvement of the living conditions of its residents, officially making the al-Salām district a “formal” area.

Despite the numerous development projects that have taken place in the Greater Cairo region and other Egyptian cities after the development of al-Salām district, the latter is still considered to be one of the most sustainable development projects. The al-Salām district development plans were based on two principles: firstly, that people are the real “owners” of development, and they have more significant roles in the development of their neighborhood, and secondly, that land is a resource that must be harnessed to meet the needs of the people, not a financial source used to increase state resources.

This article seeks to shed light on this project as one of the great examples in the field of urban development and projects targeting the poor areas in Egypt, by recognizing the factors that led to its success and the mechanisms of transferring theory to practice. Additionally, this article aims to deduce the factors of how the state determines the way it deals with unplanned areas, in an attempt to understand why this model has not been replicated again in other districts.

This project is significant because it was one of the first projects that recognized the poor urban areas in Egypt built by people themselves, where the residents have the right to a decent life and adequate housing. This project also directly identified the main problems facing those areas after defining them as an “unplanned progressive urban settlement.” Accordingly, the physical components of the project became clear: housing, road network, infrastructure, and services. The other addition of the project, in the urban development field, was the concept of “adequate housing,” where a ‘house’ was considered more than just four walls and a roof. This idea stems from the “natural housing” process, that is, the ability of the residents to formulate and build their housing gradually in line with their daily and future needs, as well as resources available to them.1 Project consultants saw the “natural housing” process as a valuable asset that can be maximized upon developing unplanned areas.

On this basis, the project presented the “Land & Services” approach as a development strategy to gradually improve the living conditions of the residents in unplanned areas, using the value of natural housing in a formal setting. This model relies primarily on a genuine partnership between the residents—as actors rather than recipients—and local authorities. In this model, the role of the government is limited to the allocation and sale of the land to the beneficiaries at prices commensurate with their income levels, and to gradually equip that land with infrastructure and services through the proceeds of land sales at a level that suits the needs and preferences of the residents, on the condition that residents to bear the cost of establishing their housing (Clifford Culpin and Partners 1983). Therefore, this project’s uniqueness is thanks to its successful use of the theoretical framework under the existing laws and legislation.

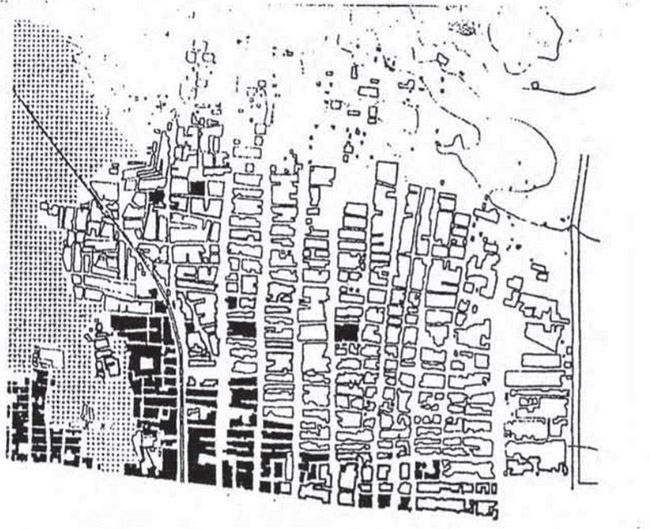

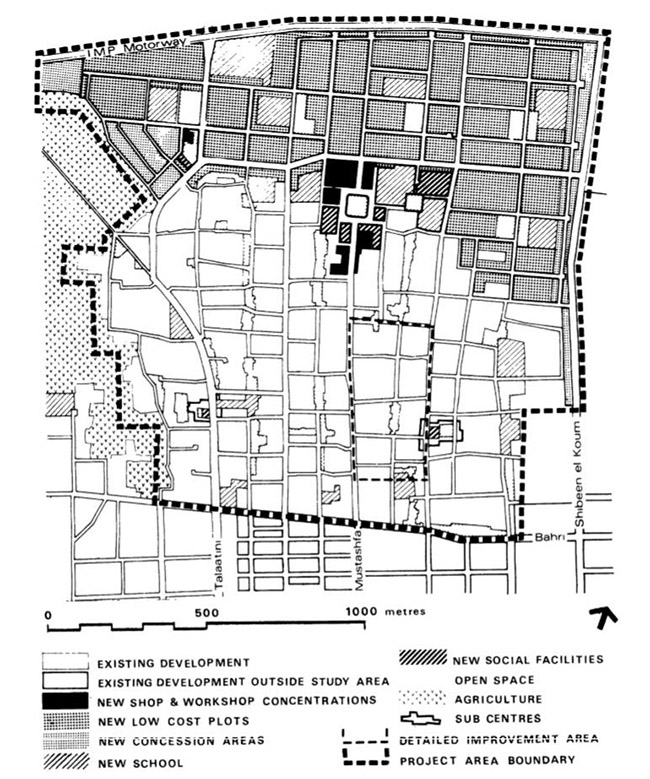

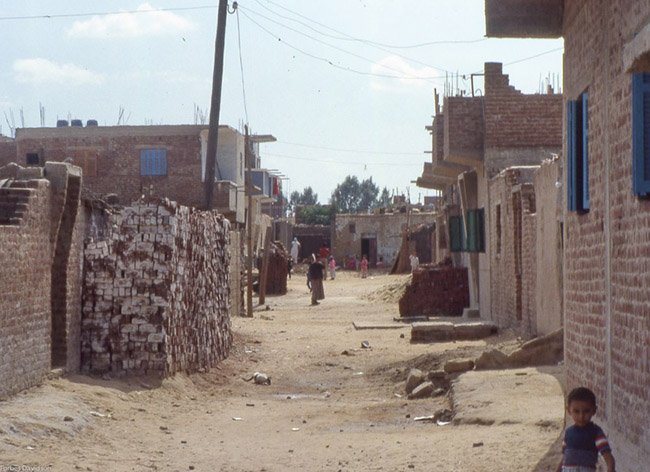

The current urban fabric of the al-Salām neighborhood inside the urban block of Ismāʿīlīya. Source: Tadamun 2016

The Situation Before Development

Before the project, the al-Salām District was called “al-Ḥikr” because the residents were paying the governorate in order to use the land. It was inhabited by about 37,000 inhabitants.2 The al-Ḥikr District was established around 1967 thanks to the efforts of the residents (like many other unplanned areas) on state land as an extension of the pre-existing city (Housing and Building Research Center 1998).3 The urban fabric of the area was semi-organized, as residents built their homes along the existing road network north (Davidson 2016). The 1967 war affected urbanism in Ismāʿīlīya and al-Ḥikr, as they were converted into military barracks. ʿAm ʿādil, a resident of the area, told us that their house became “al-Mīz,” a place for soldiers to eat. In the aftermath of that war, most of the residents of Ismāʿīlīya were displaced, the fate of many residents of other cities across the [Suez] Canal. Normal life gradually returned to the city after the war in 1973, when residents were allowed to return to their homes. During that period, Ismāʿīlīya witnessed a steady increase in residents and high rates of migration from other governorates. In light of the increase of residents, which had not been taken into account by the government’s development and housing plans, unplanned areas became the only source of alternative housing for the increased number of people. Consequently, the urban character of Al-Ḥikr was generally straightforward, with unpaved roads and a lack of utilities and services. The north of the district, however, differed from the south in terms of building materials and building elevation. In the north, most of the houses were one-story buildings built using mud or mud bricks and cheap local materials, at a distance from each other. The interstitial spaces between houses increase heading north as buildings were scattered across the land. In the south, three-to-five-story buildings can be found, made of concrete. Generally, there were no utilities or services in the area except for some public water taps (Housing and Building Research Center 1998).

The general location of al-Ḥikr before the development project. Source: Housing and Building Research Center 1998.

The Idea’s Inception

Sadat wanted to rebuild the country quickly after the end of a challenging period in Egypt. One of the pillars of the state’s development strategy was the reconstruction of the Canal’s cities because of their economic importance. A general scheme was therefore prepared for the Governorate of Ismāʿīlīya in 1976 with the aim of accommodating about 1.3 million residents by the year 2000. The number of the governorate in the year of the scheme was estimated at 353,000 inhabitants. The scheme was prepared by the British consulting firm “Clifford Culpin and Partners” under the supervision of the Ministry of Housing and Construction. It was funded by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) (Housing and Building Research Center 1998).

The main idea of the scheme was to put the informal private sector in charge of the provision of the housing units. Consultants realized that this sector adds more occupied units to the national housing stock than what the state can add. Field studies showed that if people own land legally, provided with the services they need, they will be more likely to build their own houses. On this basis, the consultants—including John F.C. Turner—proposed a realistic approach to support and regulate what they called the “Natural Housing Ecosystem” (Davidson 2016).4

The basic idea was to select an existing, unplanned area adjacent to a new, empty area, and then create a detailed scheme that combined both areas. The scheme was based on the “Land & Services” approach used in international projects to develop unplanned areas (Clifford Culpin and Partners 1983). In 1977, the Governor of Ismāʿīlīya asked the Consultative Group to select several unplanned areas for pilot projects, to lead the path for implementing the policies proposed in the 1976 scheme (Davidson 1981).5 The al-Ḥikr area was chosen as the area where a pilot project can be implemented. This selection was made based on several criteria in addition to the area’s need for development: the existence of a catalyst for development, the absence of obstacles to development, and the availability of adjacent empty areas. The al-Ḥikr neighborhood fulfilled all of these requirements. The consultants found that the desire of the residents to invest some of their time and income in improving their housing was a significant catalyst for the success of the project. As al-Ḥikr was located in the far north of the city, there was enough land to carry out the project; accordingly, in 1979, the Governor issued a decision to allocate lands for the project. The development of the area depended on two main factors: first, the ability of the residents to afford it, from the purchase of the land to provisioning it with utilities; and second, the needs of the residents during the development stages of the project, linked with their ability to save and invest.

Phases and Steps of the Project

To assess the realistic possibilities of this approach required a detailed examination of the living conditions of the families, their ambitions and obstacles, and an understanding of how an urban planner could help these families. The project began by studying a random sample of households to understand the housing system and people’s actual needs and problems. The consultants then developed several objectives to move the scheme into effect through the “Land & Services” approach, which was mainly self-financed by the residents

The objectives of the pilot project in the al-Salām district were:

1. The project should be realistic, not require radical changes in the governing institutions and legislation.

2. Development should be based and dependent on the living conditions of the residents, taking into account the social ties, economic activities, and urban nature of the area.

3. The project aims to create an internally integrated society that includes and ensures opportunities for all its groups which is externally integrated with the surrounding environment.

4. Development should provide plots of land with multiple areas and services to suit different income levels.

5. The project should be implemented quickly with minimal external financial support.

6. The project is managed by local authorities with the help of external experts.

7. The development project is replicable in other areas.

The al-Salām District Scheme

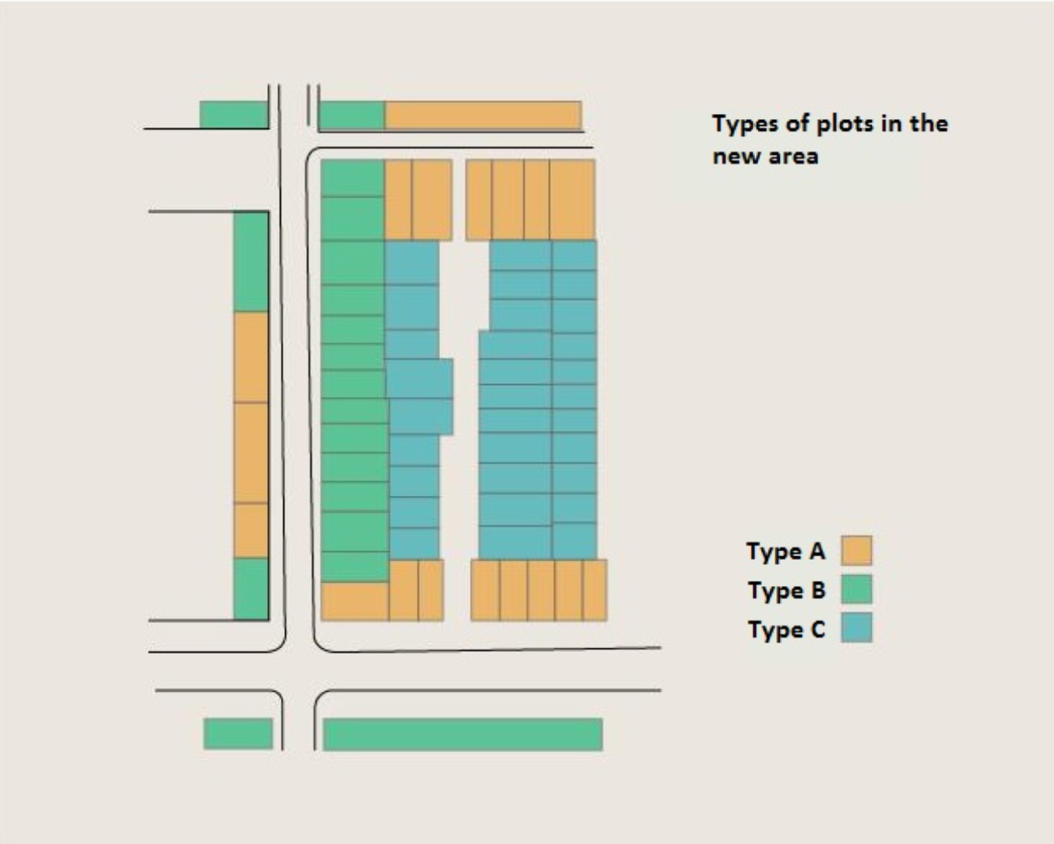

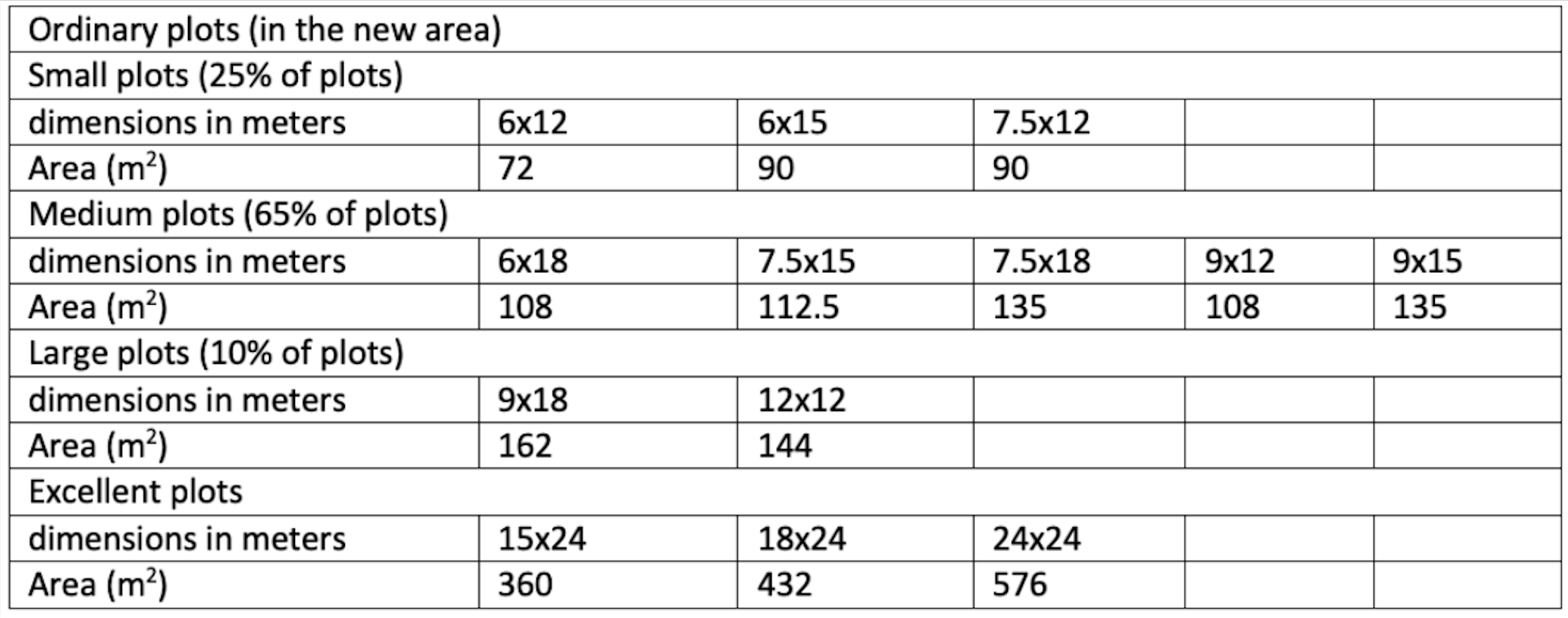

The al-Salām District was divided into two integrated parts; the first part was the improvement of the existing area of 312 acres, and the second was the development of the new, 222 acre plot of land which was north of the existing area (Clifford Culpin and Partners 1983). In the existing area, the land was re-planned and subdivided. Then, the lands of the existing area were sold to the residents as the first phase of the project. The aim of the re-planning and partitioning was to facilitate and reduce the cost of supplying the area with infrastructure as well as to create areas for localization of services, without having to remove many buildings. ʿAm ʿādil explained that the project team did not demolish any building made of concrete because the owners had invested all of their capital to build them. The project team made sure that the first beneficiaries of the project were the ones most affected by the re-planning process (Davidson 2016). In the new area, on the other hand, plots were divided in order to serve different groups of families according to an estimation of their average income. On this basis, the team developed a phased plan to provide the combined area—comprising both the existing and new areas—with public infrastructure upon completion of the project, as long as these facilities were connected at the start of the project, even if they were rudimentary, such as public water taps and cisterns (Davidson 2016). The cost of supplying utilities based on the size of the plot and the level of related services was divided into seven levels; therefore, land prices were determined based on their location and connected utilities, as shown in the following table (Clifford Culpin and Partners 1983).

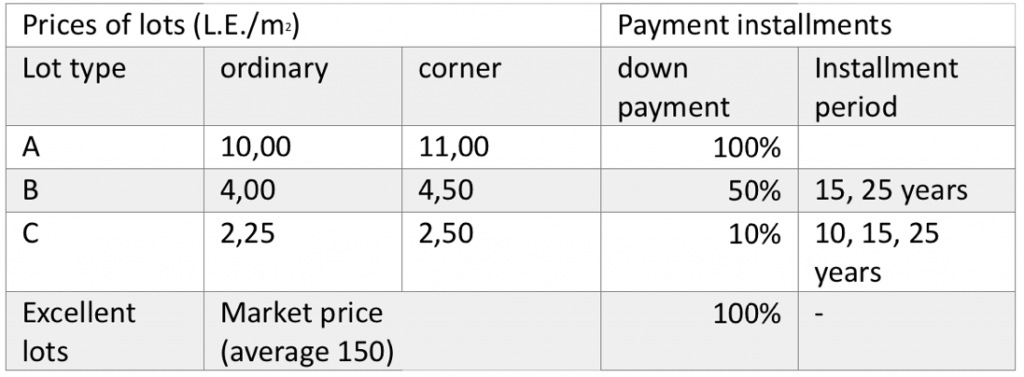

Types and prices of plots in the al-Salām District Scheme. Source: Clifford Culpin and Partners 1983

The land was sold at prices suited to the target groups, and to anyone who proved to be holding or leasing a plot of land or house prior to the start of the project in June 1977. In cases where unrightful claims were made to obtain unfair plots of land, reference was made to aerial photographs taken in April 1977; that is, just before the start of the project. In the new area, the land was sold to citizens via a lottery, and the priority of allocation was restricted to the residents of Ismāʿīlīya. Priority was given to families renting in the existing area, followed by those who were residents of Ismāʿīlīya before displacement. The applications of citizens who owned other units in Ismāʿīlīya were not accepted, whether private units or through any government agency such as the Suez Canal Authority. In addition to these limitations, and to ensure real development in the district, the beneficiaries were required to start building their homes within the first year of the date of receiving the plot.

Project Management

Project Committee

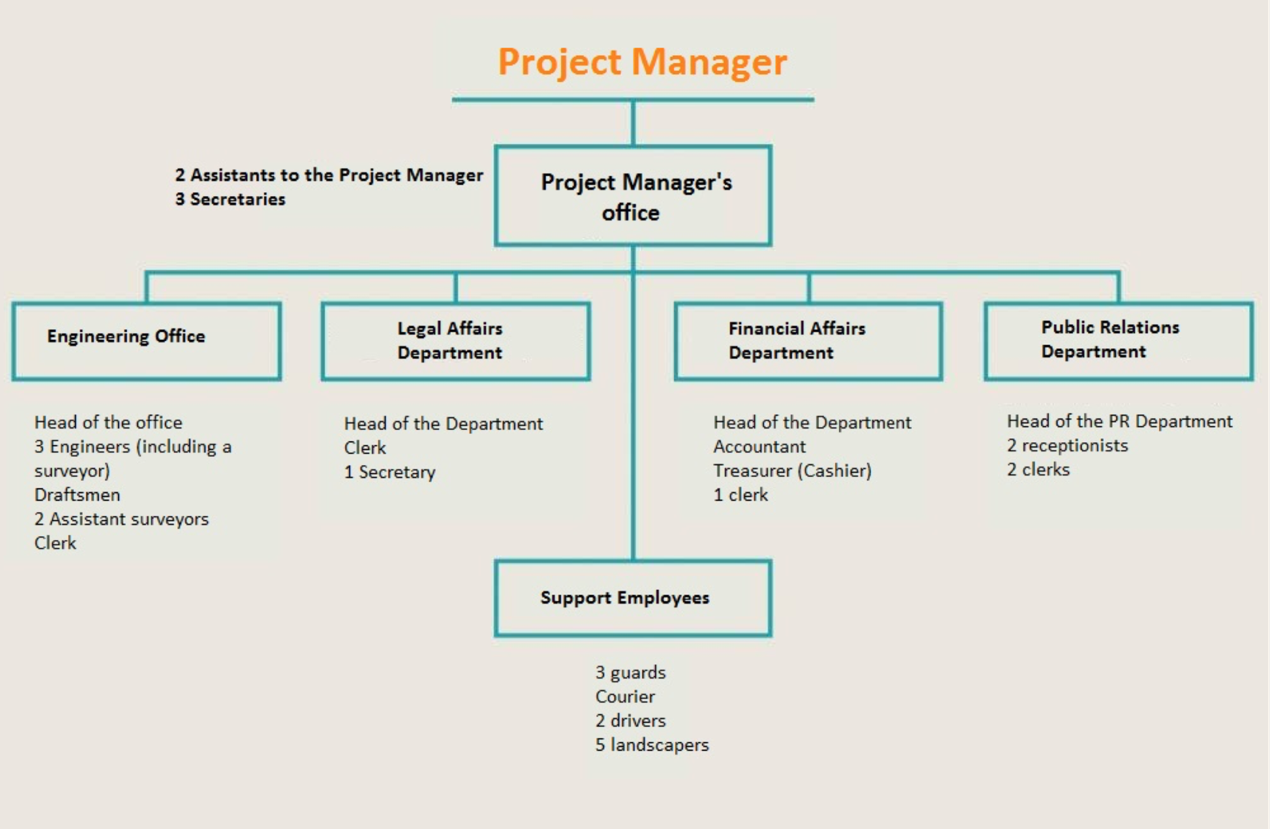

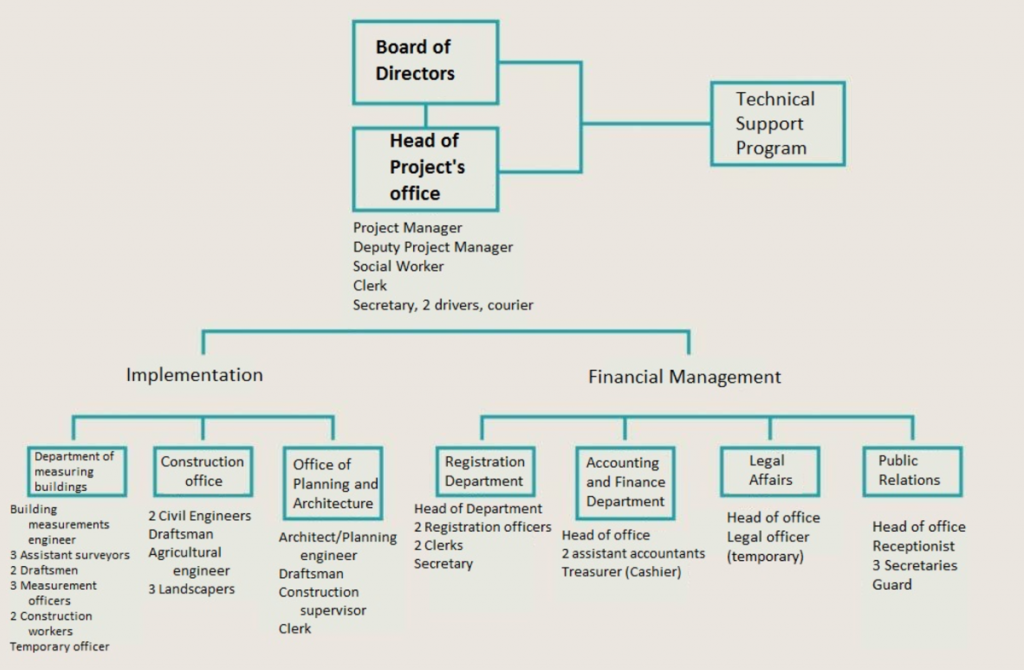

Most of the sources and evaluators of the al-Salām development project stated that one of the main reasons for its success was the Governor’s establishment of a competent committee to manage the project (Clifford Culpin and Partners 1983; Matteucci 2006; Research Center Housing and Construction, 1998; Davidson 1981; Blunt 1982). This committee had broad mandates. In addition to its primary mandate as the technical lead of the project, it also had administrative and financial mandates, which gave it the power to make decisions without consulting with local government authorities. The committee of the project had the mandate to buy and sell land, as well as manage the budget of the project and the conclusion of contracts. This precipitated the implementation of the project since the committee was not greatly affected by bureaucracy. However, those mandates did not go unchecked since the committee had to further report to a select committee headed by the governor to monitor the flow of funds. The committee was initially composed of five departments (as shown in Figure), in addition to the Office of the Project Manager, by 1980, it was expanded to include eight departments (Blunt 1982).

The organizational structure of the project committee in 1978. Source: Blunt (1982) and Graphics: Tadamun Initiative

The organizational structure of the project committee in 1980. Source: Blunt (1982) and Graphics: Tadamun

Project Committee Responsibilities:

1. Conduct the necessary surveys and studies.

2. Prepare all detailed plans for the project.

3. Provide technical support to the people in the construction of their homes.

4. Coordinate with the city council regarding the project.

5. Represent the residents and raise their demands and needs before the government agencies.

6. Allocate and sell land to the beneficiaries, conclude contracts with them, and collect the revenue.

7. Facilitate borrowing through the Microfinance System.

8. Coordinate and negotiate with the authorities responsible for providing the area with infrastructure.

9. Beautify the area’s sites; in other words, conduct the forestation of the area and plant green spaces.

Board of Directors

The Project Committee was responsible for coordinating with all stakeholders, to ensure the best and quickest communication possible. Furthermore, the Governor established a Project Board in 1978 (Wilbur Smith Associates 1990). On paper, this board included 23 representatives from local and government agencies concerned with urban development, such as the Ismāʿīlīya governorate, the city council, the housing and finance directorates in the governorate, the property management department, and the project manager. In reality, the board included representatives of the ruling National Democratic Party (NDP), the Survey Department, the Governor’s engineering adviser, and a legal adviser in addition to the aforementioned members. The Representatives of the Suez Canal Authority and the Electricity Company were added one year later to the board (Blunt 1982).

Responsibilities of the Board of Directors

1. To support the project authority, when needed, with the necessary competencies.

2. To ratify development proposals as well as project expenses.

3. To ensure cooperation between all parties involved in the project.

4. To decide how to implement the policies of the project.

Resources and Funding

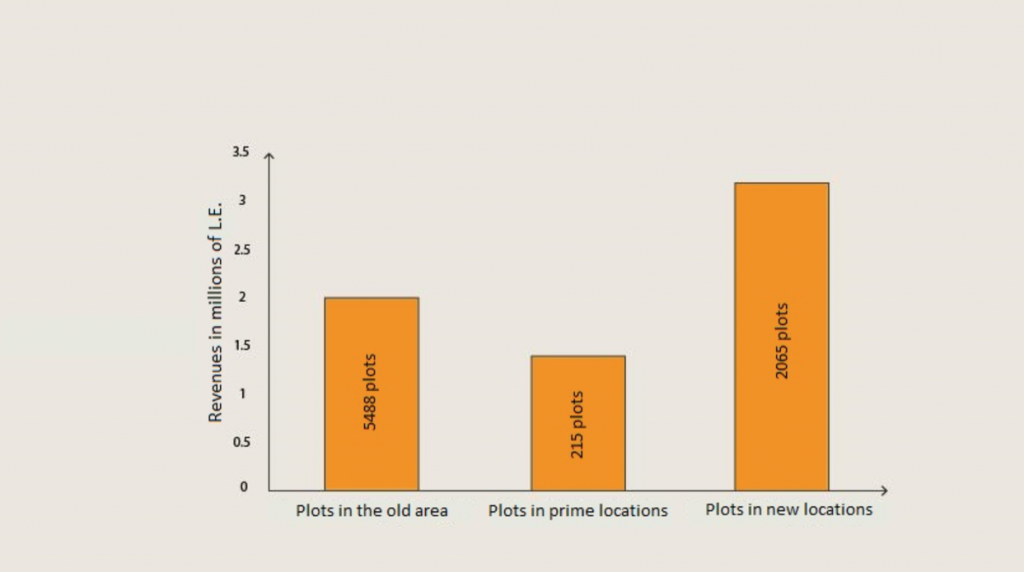

Self-financing is the primary source of funding for the “Land & Services” approach and has been the primary source of financing for development in the al-Salām District. Self-financing relies on the sale of land as a significant resource of income under the assumption that the legalization of land ownership would serve as a substantial incentive for people to invest in the construction and development of their homes. According to a study conducted by the Housing and Research Center, the number of added housing units was about 9,000 units by the end of 1985. The study estimated people’s investments at about 50-70 million Egyptian pounds at the time, depending on the cost for the state to build economic housing (Housing and Building Research Center 1986.) However, these investments are likely overvalued, as people are building their homes at a lower cost than the state can. This is in addition to the revenues from land sales, which supposedly returned to the area in the form of infrastructure and services, which in 1985 amounted to about 6.6 million Egyptian pounds (Housing and Building Research Center 1998).

The residents’ own financing was not the only resource of the project. Given the economic conditions experienced by the country after the state lost resources and people during the war, Sadat adopted a policy of openness to attract both internal and external investments in various fields (Khalifa 2015). The government could not continue to be the largest investor in the country as it used to be under Nasser, and these constraints were reflected in the project of developing and improving al-Salām District. The project did not rely on any public resources or plan to generate profit; rather, it planned to rely on external funding as a resource. The master plan of Ismāʿīlīya was developed with funding coming from the UNDP (Wilbur Smith Associates 1990). The British government also donated a grant of £65,000 as the founding capital of the al-Salām district project until the sale of the land yielded its proceeds. The grant was directly employed in the construction of the project headquarters as well as the preparation of surveys and studies (Clifford Culpin and Partners 1983).6 Additionally, the US Agency for International Development (USAID) provided funding to contribute to the area’s infrastructure (Wilbur Smith Associates 1990).7

Obstacles and Constraints

Despite the challenges faced by the development project of the al-Salām district, it was considered a success by many experts, studies, and residents interviewed by Tadamun. The main obstacles can be categorized into three groups. The first and main category was the ideological difference in the nature of the project between foreign consultants and local authorities in Ismāʿīlīya, especially regarding the new area (Davidson 2016). Although they agreed on key strategies, each side’s vision toward the project was different. Foreign consultants saw the project as developing the new area and allocating it to low-income residents, basing this approach on what they called natural housing. However, the local authorities wanted to profit from the new lands under the policy of openness, and use it as propaganda for the ruling party. From their perspective, the reconstruction of Ismāʿīlīya should be the first achievement and a reflection of the policy of openness (Matteucci 2006).

Secondly, the project initially faced some technical challenges in terms of specific competencies—both quantitatively and qualitatively. The nature of the project was new, therefore, the required skillsets to complete the project were not accessible in the community. Furthermore, not all the necessary specialties were available; for example, the project initially lacked a road and a sanitation engineer. Over time, the experience of the staff grew alongside the number of employees, bringing a new set of complications with it. The most prominent of these challenges was the tension between the Project Committee and the Project Board. The mandate of the Project Board—budget approval and staffing—was no longer sufficient to its members, compared to the broader executive mandate granted to the Project Board. Decisions that satisfied all parties became more difficult to reach, causing disruptions to the development process in the district, but the Governor of Ismāʿīlīya ultimately had the final say (Matteucci 2006).

The third challenge facing the project was the lack of resources, which impeded the rate of development in the area. The centrality of resource allocation had not provided the capital needed to enable the governorate to spend beyond the central plan (Matteucci 2006). On the other hand, the primary source of funding was land sale to the people, and with inflation, the proceeds of these sales were not enough to make the necessary development. Foreign consultants suggested a small increase in the price of lands, however, the local council did not approve it, and ultimately the use of external funding helped to overcome this obstacle (Davidson 2016).

Results and Effects

The development of the al-Salām District had consequences and implications that we should examine. According to a study conducted by the Building and Housing Research Center in 1986, the population in the area increased from about 37,000 to approximately 70,000 after the project contract ended in 1985. This contradicts the official census issued by the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics, which estimated the population at about 45,000 inhabitants.

In 1985, the al-Salām district witnessed both an increase in the proportion of occupied land as well as an improvement in building materials, shifting away from raw brick to reinforced concrete and red brick. Additionally, the percentage of buildings under construction decreased in the existing area despite the empty lands, which indicates that the project achieved its objectives. As the feelings of stability of residents increased, the buildings were later made of reinforced concrete. Some buildings remained under construction based on the available resources, and needs of the people. The housing demand in the new area was higher than in the existing area. The elimination of the limited income requirement for land allocation indicates that the groups that acquired the land were not likely among the low-income target groups, especially since construction in the new area was moving at a faster pace than in the existing area. This appeared to be because the buildings in the new area were purchased solely for investment purposes, and thus were occupied with tenants only (Housing and Construction Research Center 1986).

By the end of the 1985 contract period, the area as a whole was not served by the needed public infrastructure facilities. However, this did not prevent the increase in prices in the al-Salām district. Land prices in 1985 increased to 1,000 Egyptian pounds/m2 for plots on main streets, which were close to land prices in Ismāʿīlīya Center (Housing and Building Research Center 1998). This brings us to the question: who benefited from the project? What happened to those who bought the land from the project committee? Did the project succeed in improving the living conditions of the people? Did the people sell the land they received at the market price and settled in other unplanned areas?

It is clear that the beneficiaries of the project differ, both the original residents of the area, as well as the middle- and high-income groups, but not low-income ones. For the original residents of the area, a large percentage of residents witnessed improved living conditions as a result of the project. When we met with ʿAm ʿ ādil, (a resident of the area who had been displaced before the war and whose family bought the land on which the house is now located), he indicated that he is now benefiting from renting a pharmacy on the ground floor of the house. ʿAm Aḥmad, one of the original residents before the displacement, who also owns a house in the area, said that he used the ground floor to open a grocery store. As for the targeted groups from outside the area, the elimination of the limited income requirement for acceptance into the second lottery led to more applications from the middle- and high-income category. A Housing and Building Research Center study indicates that there is an “unofficial” estimate that 75 percent of the lands were resold from residents, which emphasizes the idea that middle- and high-income groups were targeted more heavily (Housing and Building Research Center 1986). These developments over the course of the project contributed to the creation of a homogeneous and integrated society of different income groups, which is in line with what the planners hoped. In addition, the income differences between the various classes were not significant and thus allowed homogeneity between those classes.

Currently, the al-Salām district, or shiyākha al-Ḥikr, as it is officially named, occupies an area of 632 acres of the land of Ismāʿīlīya. It is the home to more than 81,000 residents (Census 2006).8 Nearly four decades later, thanks to the project, the al-Salām district is currently a planned area with all of the needed infrastructure including electricity, drinking water, sewage, and telephone lines. It also has all the needed services including schools, hospitals, phone, and postal services.

As for the road network, the difference between the old and new areas remains clear. The old area, south of al-Salām Mosque, is characterized by relatively irregular streets and unpaved side alleys. In contrast, the streets of the new area north of al-Salām Mosque have a regular grid pattern. Despite the fact that nearly four decades have passed, construction in the area is still thriving, with some 12-story buildings within sight, some under construction, and still others uninhabited. These buildings were constructed in violation of the decision of the governor to set a maximum of a 6-story building in Ismāʿīlīya, according to the head of the General Authority for Urban Planning in the Suez Canal Area. The al-Salām district remains one of the central areas in Ismāʿīlīya, where the price of buildings reaches 4,000 LE/m2 in the main streets.

Sustainability and Replicability of the al-Salām District

What happened in the al-Salām district is the implementation of the concept of sustainable urban development, which, according to the Unified Building Law No. 119/2008, is defined as “managing the process of urban development by optimizing the natural resources available to meet the needs of the present generation without affecting the opportunities of future ones.” The project planners took into consideration the lives and development of the residents and employed the land to meet the people’s needs through a flexible and realistic management process. This project gradually improved the residents’ living conditions according to their needs and resources. Additionally, public funds were used more effectively to serve the most target groups, as land was treated as a resource to improve the lives of the residents rather than as financial support to increase the state’s financial revenues. This method contrasts current housing strategies, which provide ready housing units that do not accommodate the different needs of families, and deplete public resources to build complete infrastructure networks that serve only a small number of citizens.

The project for the development of al-Salām district was not intended to develop only one area. The consultants hoped to create a system that would enable people—with their values, customs, and surroundings—to meet their needs and improve their living conditions how the residents themselves deemed most appropriate but also within the official entities’ agreed and accepted framework (Davidson 2016). In 1981, the Governor issued a decision to establish the Planning and Development Authority in Ismāʿīlīya—one of the proposals of the Master Plan—as a governing body with financial and legal discretion; this authority had a role similar to the al-Salām development project, but at the governorate level, where it was mandated to inject resources at will among various areas. This entity consisted of staff members who participated in demonstration development projects. The Ismāʿīlīya Planning and Development Authority (PIDA) followed, and updated, the 1976 scheme in the development of other unplanned areas in Manshiyyat al-Shahadāʾ, al-Qantara Sharq, and five other areas (Wilbur Smith Associates 1990.) These other projects were not developed with the “Land & Services” approach because of the challenges associated usually with that approach at that time, although the al-Salām district had overcome them. In addition, the al-Salām district was chosen in the belief that the implementation of the development process would be more straightforward. These challenges were limited to the lack of required human and financial resources and an insufficient transfer of executive expertise or the building of local cadres to undertake similar projects.

On the other hand, these projects have not been financially supported by donors, mainly since the provision of infrastructure in the al-Salām district has been significantly aided by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). However, newer projects have been funded and supported by third parties, preventing the al-Salām district experience from being replicated in Ismāʿīlīya, or in Egypt more generally.

Tadamun’s Vision

While there are always multiple perspectives, one may conclude from this situation that unplanned areas are areas with “natural housing,” while another may view them as “informal areas.” The Egyptian state’s assimilation of the unplanned regions has evolved from areas with “natural housing” to “slums,” evidenced by the evolution of Egyptian laws regarding land ownership and the abolition of certain types of ownership, such as al-Ḥikr.

Consequently, a modern state’s conception of areas which depend on residents’ efforts logically arrives at the term “slums.” These different perceptions of unplanned areas result in different ways of dealing with and developing them. The state’s continued support for new cities and social housing is linked to the state’s perspective on unplanned areas. In order to understand the difference between these two views, one must first understand two main factors.

The first factor is the value of the land. The development approach of the first perspective deals with land as a resource for the development of the project, with a social function, as in the al-Salām district project. The other perspective deals with the land as a source of income and investment, as a reflection of Egypt’s policies of openness and economic reforms. Yet some questions remain: what is the real value of the land, who determines it, and who has the right to enjoy this resource?

The second factor is the product or form of development, which is often seen in government agencies dealing with informal settlements. In the al-Salām district project, for example, local government agencies were not satisfied with the shape of buildings; they preferred modern building materials over their traditional counterparts. They were also not convinced of the idea of progressively supplying infrastructure. This was confirmed recently by President El-Sisi when he mentioned the “Build Your Home” project, which was based mainly on “Land & Services” Approach.

“You said the idea of ‘let your son built your home,’ correct? Take the youth to see that initiative … Take the youth to see that initiative … the randomness that exists. We do not do that… We do not do this; we do a well-integrated and respected work.”

When he references “randomness,” he is not referring to the behavior of citizens in construction, but rather to the randomness that accompanied the supply of infrastructure by the Ministry of Housing, which allocated land to the residents before providing the necessary facilities and services. President El-Sisi also pointed out that the goal is to build an integrated civilized society such as in Asmarāt, or social housing projects, which are still the main thrust of the state’s attempt to solve the housing problem in Egypt.9

The state’s perspective on the value of land and the form of development was reflected in urban policies in Egypt. In the view of the state, the new cities and social housing projects are the best solutions to the problems of Egyptian urbanization, despite the burdens caused by the state in return for not meeting the needs of ordinary people. The cost of increasing the size and numbers of new cities could be more than double Egyptians national spending on education and health combined. In contrast, the new cities did not achieve the desired number of inhabitants. In addition, a small proportion of land in the new cities has been allocated to medium and economic housing, and there is no data on whether the allocation of such land actually meets the housing demand for these groups or not. What is certain, however, is that these housing units do not end up in hands of the poor and middle classes and certainly do not meet their job, transportation, or education needs, among others.10

Many urban planning theories have emerged following this shift in the Egyptian perception of such areas. Some of those theories indicate that countries with their institutions and experts cannot, and should not, be the only actors in the process of urban development. This is not only due to the limited public resources, as in most developing countries like Egypt, but also to a theory called the “complexity theories of cities.” This theory suggests that cities are too complex to be comprehensively planned since the process of evolution is unpredictable and not fully controllable; instead, there must be a flexible system which stems from the dynamics of the city and its residents and that fits and ensures the needs of its citizens. The Egyptian state is thus contradictory in terms of development as it is no secret that Egypt has minimal resources and Egyptian officials have repeatedly confirmed that fact. In terms of the effectiveness of citizens in the planning and development process, the state does not appear to guarantee this one way or another. The legislative framework for planning and development, as found in Article 78 of the Egyptian Constitution and the Unified Building Law 119, always indicates that the sole actor for planning and development is the state.

Thus we see that the experience of the al-Salām district is of great importance in the field of urban development in Egypt, not only because it created an integrated and homogeneous society of various groups, but because the consultants realized that no scheme is predictable nor is it controllable. In addition, this experience has confirmed that under a carefully structured formal system based on community action, citizens can be real actors and investors in the development process, not just as recipients—as they are in existing social housing projects. That is why we consider the al-Salām district experience to be another missed opportunity to balance the reallocation of public resources, like in the Zinhum Housing Experience—which we addressed in a series of Planning in Justice articles—as well as the needs of citizens as individuals in society.

The success of previous experiments remains conditional on their specific circumstances. Both projects have been politically supported; Zinhum Housing was supported by [The Former First Lady] Suzanne Mubarak, and the al-Salām district was endorsed by Sadat, in his strategy to rebuild the city of the Canal. Clearly, political support at all levels, from the President of the Republic to a parliamentary election campaign, is the first step to change the methods and strategies of development at these different levels. Social housing projects remain the most politically supported. What is the state’s view in continuing to support these projects despite their inability to meet the needs of citizens and these citizens resorting to “slums” or natural housing?

References

Archnet. 1983. Photographs of Ismailiyyah Development Project. Retrieved from http://archnet.org.

Blunt, Alistair. 1982. “Ismailia sites-and-services and upgrading projects – A preliminary evaluation.” Habitat International 6 (5-6), 587-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-3975(82)90026-1l.

Badr, Aziza. 2001. Informal Urbanization in Egypt. Cairo: Supreme Council of Culture.

Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS). 2006. The final results of the general census of residents and housing conditions – Ismā’ylīa.

Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS). 1986. The final results of the general census of residents and housing conditions – Ismā’ylīa.

Clifford Culpin and Partners. 1983. Urban projects manual (Liverpool University Press in association with Fairstead Press). Retrieved from https://www.ircwash.org/sites/default/files/205.42-83UR-18728.pdf

Davidson, Forbes. 1981. “Ismailia: From master plan to implementation.” Third World Planning Review 3(2), p. 161–178.

Davidson, Forbes and el-Hefnawi, Ayman. 2008. Evaluation of the project “Participatory Slum Upgrading in El-Hallous and El-Bhatini, Ismailia, Egypt.” Retrieved from erc.undp.org.

Housing and Building Research Center. 1986. Seminar of development projects in Salām District in Ismā’ylīa. Cairo: Ministry of Construction and Housing.

Housing and Building Research Center. 1998. Providing small plots for low-income people as part of an urban development pilot project. Cairo: Ministry of Housing, Utilities, and Urban Communities.

Ismāʿīlīya Governorate Website. 2014. Second District Data. Retrieved from http://www.ismailia.gov.eg/second_district/Pages/display_second_info.aspx

Khalifa, Marwa A. 2015. “Evolution of informal settlements upgrading strategies in Egypt: from negligence to participatory development.” Ain Shams Engineering Journal 6(4), p. 1151-1159. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2015.04.008.

Matteucci, Claudio. 2006. “Long-term evaluation of an urban development project: the case of Hai El Salam.” Unpublished paper presented at NAERUS conference, Darmstadt. Retrieved from http://n-aer/sat/workshops/2006/papers/matteucci.pdf us.net/web.

Wilbur Smith Associates. 1990. Local Development II: Urban Project. USAID.

Meetings

Ahmed Khairy. (July 19, 2016). Visit al-Salām District.

The worker within Al-Salām Mosque. (July 19, 2016). Visit al-Salām District.

ʿAm Ahmed. (July 19, 2016). A visit to al-Salām District.

ʿAm ʿādil. (July 19, 2016). A visit to al-Salām District.

A realtor. (July 19, 2016). A visit to al-Salām District.

Hisham Jauhar. (July 18, 2016). Al-Salām District between theory and practice.

Davidson. (July 25, 2016). What happened in the project of developing and improving al-Salām District.

Related Resources

Constitution of the Arab Republic of Egypt. 2014

Website of one of the project consultants

We want to thank Professor Forbes Davidson (one of the Al-Salām District project consultants) for accepting our invitation to meet with him. We have a great deal of appreciation for his experience and extensive knowledge which helped us in publishing this article.

Footnotes

1. “Natural Housing” is a term used by the consultants of the “al-Salām” project on the gradual construction method adopted in poor or unplanned areas.

2. Al-Ḥikr lands were an official type of land leased from government entities in accordance with Law No. 52 of 1940 on the division of land for construction and the Egyptian Civil Code. In the “Intermediary to Explain the Civil Code,” al-Ḥikr [Monopoly] was defined as “A sub-right of property. The monopoly contract gives the monopolist an in-kind right on unused land, which would allow him/her to use that land to build, farm, or perform any other purpose for a certain fare.” However, several successive legislations have been issued to end this form of land use, starting with Law No. 649 of 1953, Law No. 295 of 1954, and Law No. 92 of 1960.

3. It was not possible to know the actual history of the emergence of the area of ”al-Ḥikr,” but most probably the origin of the area dates back to the 1930s or 1940s. This is due to the circumstances of the emergence of the city of Ismā’ylīa, which was in the second half of the nineteenth century, and also that the law No. 52 of 1940 on the division of land for construction included dealing with the land like this, and that the issuance of the first laws limiting the monopoly was in 1953.

4. John F.C. Turner is one of the most important pioneers who have worked and considered the development of poor and unplanned urban areas.

5. The “Land & Services” approach – then – was the new methodology for the development of the world’s poor urban areas, as a parallel alternative to social housing programs aimed at redirecting public resources in their development. This approach was adopted by the World Bank in the post-1972 period in many development projects (Blunt, 1982; Davidson, 1981). For more information about this approach, visit this site.

6. In 1977, LE 1 ~ £ 0.75

7. Available sources did not say how much funding USAID provided

8. The al-Salām district is administratively affiliated with a second District in Ismāʿīlīya, which was established in conjunction with the project by decision No. 412 of 1979 by Dr. Abdel Monʿim ʿamara, the Governor of Ismāʿīlīya at the time. The Second District is considered the most high-density part of the city, according to the 2006 census. Ismāʿīlīya is administratively divided into three districts. The density of the second district is estimated at 133 individuals/acre compared to the first and third ones (~22 individuals/acres and 33 individuals/acres, respectively). These densities were calculated based on data on the area of Ismāʿīlīya districts from the governorate site.

9. The Asmarāt district is one of the state’s projects to resettle the residents of the Shahba area in Manshiet Nasser. This project differs from resettlement projects in that it is not far from the heart of the city.

10. To learn more about the New Cities Policy, please refer to the New Cities Policy in Egypt: Modest Impact and Absent Justice

Comments