52 Fouad Street: How did the Sigma company shift this property from the past to the present?

By: Aya Samir Badawi

This article is an outcome of the “Know Your City-Alexandria” workshop organized by the Tadamun Initiative in January 2017. The views published in this article are the author’s and do not reflect the opinions of the Tadamun Initiative.

In December 1999, Alexandria became the first governorate to prepare a list of its heritage buildings and areas. Seven years later, complementing this effort to preserve its history, the governorate of Alexandria formed two committees as well as working groups of professors and researchers to review this list and provide detailed data on buildings with a unique architectural style. This effort resulted in the “Preservation of the Heritage Buildings of Alexandria Governorate List,” which includes 1,135 heritage buildings. Law 144 of 2006 (on the regulation of the demolition of in-good-standing buildings and installations and the preservation of the architectural heritage) forbids the demolition of the buildings on this list.

This bright start to the preservation of the Alexandrian heritage, however, took a turn when many of these buildings did not receive the necessary attention, restoration, or maintenance. The story of each building was the same: a lawsuit requests the removal of this building from the heritage list. Then, demolition takes place to make way for a new-multi-story building, which generates higher profits for its investors. Despite increasing calls for severe legal actions, these protected buildings continue to be demolished and vandalized, posing a grave threat to Alexandria’s heritage.

This paradox—the preservation of the buildings vs. rapid financial returns—opened the window for Sigma Real Estate Investments to enter the heritage preservation arena. The heritage value of these buildings is an asset that can be exploited for sustainable financial returns. When managing heritage buildings, Sigma follows the “Build-Conserve-Operate” approach: the company buys a building from its owners, renovates it, and then proposes the most appropriate activity to be conducted in that building, in terms of both economic and heritage value (adaptive reuse), within the relevant legal requirements. This article sheds light on one of the conservation projects Sigma Real Estate Investments Company has carried out: The El-Passage Project, implemented at 52 Fouad Street. We discuss the specific project’s success and sustainability as we attempt to understand the role of the private and public sectors in the process of heritage preservation.

The situation before development

One of the main reasons behind the infringement of heritage is that the heritage value of a registered building does not give its owner any tangible, economic benefits. This makes some of owners feel that registering their properties on the heritage list is a burden rather than an advantage. Changing legislation or tightening demolition penalties will not solve this issue, since those solutions do not address the economic aspects of the problem. Even if the state finds a balance between heritage preservation and financial return, it is not feasible to compensate owners of all registered buildings or purchase all heritage buildings from them to ensure their preservation, hence the need to consider another method to solve this dilemma: can the partnership between the public and private sectors help to conserve Alexandria’s heritage?

In addition to creating opportunities for sustainable development through the participation of both the public and private sectors, previous experiences—in countries like England, Australia, Italy, and Lebanon—show how the private sector can contribute to heritage preservation. Even in Egypt, there have been successful examples, such as the projects of the Ismailia Real Estate Investment Company in downtown Cairo. There is no doubt that the primary goal of the private sector is to profit. A model that makes investment in heritage financially sustainable, therefore, will undoubtedly attract the private sector. In other words, the maintenance of registered buildings can be the investment and the means to make a profit. Sigma Real Estate Investments has already applied that concept in its Fouad Street project. Fouad street is one of the oldest streets in the city and it is included on the Heritage List. The building dates back to 1928, and it was designed by the Greek architect N. Gripari. Initially, the building was used as a venue for the meetings of the elite Alexandrians. Before Ismailia’s development project, Al Nasr TV owned the ground floor of building 52.

The inception of the idea

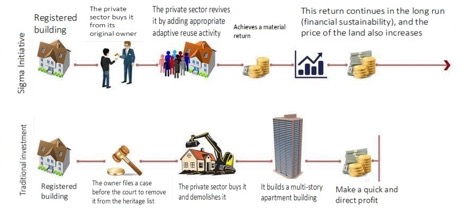

Founded in 1959 by a group of brothers, Sigma Group was initially a small company. It then expanded over the decades to include five separate areas of business: petroleum services, logistics, marine equipment, chemical industries, and real estate (especially heritage properties, where the brothers saw distinct opportunities for profit and investment). The company’s founders decided to establish “Sigma Real Estate Investments” to manage the Group’s real estate assets. More recently, when the second-generation of the family took over management, the goal evolved from mere asset management to the reuse and revitalization of those assets. On its website, the company summarizes its vision in this domain: “Adding the needed elements and activities for the revival and restoration of heritage buildings to bring them back to the present while preserving their identity and originality.” The goal is to transform these buildings into essential elements of the urban fabric. Also, the Group hopes to spread the idea of preserving heritage among the community, as well as to construct a bridge between the past and the present. This vision undoubtedly meets urgent societal and urban demands. But because the Group is a private-sector company, there is no doubt that it seeks economic returns when investing in heritage. Muṣtafā Alī Abu-‘ulā, an architect who works in the engineering department of the company, explained that investment in heritage properties is a win-win business model. The reuse of the building through economically and architecturally appropriate activities makes it profitable for the investor while serving the community by preserving its architectural heritage. The operation of heritage properties increases the long-term value of the land, achieving financial sustainability and increasing investment opportunities. Clearly, this model differs from conventional real estate investment, which aims to make a quick profit that benefits one side, i.e. the investor, who demolishes the old building and replaces it with a multiple-story residential one.

The traditional model of real estate investment versus the model adopted by Sigma (via the investment in heritage)

Phases and steps of the project

According to Abu Al-’ulā, the company focuses on what is called “the area between the two statues.” He was referring to the area located between the statue of Alexander the Great near Bāb Sharq and Wābūr Al-Miyāh, and the statue of Muhammad Alī Bāsha in Manshiyya Square. Alexander the Great is the founder of the city, while Muhammad Alī Bāsha revived the city, transforming it into a cosmopolitan one. The area between the statues contains many unique buildings. Sigma, according to its website, also owns some heritage buildings in Cairo.

The company’s approach consists of several stages, as follows:

1) Searching for a heritage property with a unique investment opportunity: This stage depends on a careful and deliberate search for properties with the potential for high returns on investment.

2) Property assessment: The property is examined to assess its status and value.

3) Feasibility study: The company’s departments (engineering and financial) then conduct a study to determine the best and the most profitable use of the building (commercial, administrative, hotel, etc.). The study aims to answer two questions: What does the market need? Can this be implemented in this building?

4) Legal Study: The legal team determines and evaluates the legal status of the building.

5) Purchase of the property: The company negotiates with the tenants (especially the tenants on the ground floor) who then move out.

6) The restoration of the property: Conducted by the engineering department and consultants. Renovating the ground floor, however, is the responsibility of the new investor.

7) The promotion of new activities

“What drives the private sector to invest in heritage is that this investor has a vision and the means to implement its vision,” said Dr. Dīnā Sāmaḥ, an assistant professor in the architecture department of Alexandria and a member of the task force that prepared the heritage list in 2006. Since Sigma operates in other domains beyond real estate, it has lawyers and financiers who can implement the different steps of the process, from dealing with tenants to suggesting the best use of the building. For the private sector, heritage preservation achieves not only financial sustainability, but also grants ownership of that property. Many of these properties are currently subject to the old rent law; therefore, the main profit comes from the added activities after development. However, the yield of these properties may increase in the future. Engineer Abo Al-’Ulā, during an interview, pointed out that the company targets both the middle- and upper-class. It does not want to replicate what Solidere has done in Beirut,1 where the old city practically became an open museum limited to the wealthy. Sigma owns several heritage buildings in both Cairo and Alexandria (up to 30 buildings, according to the website). Société Immobilière, on 52nd Street, Alexandria, is one of the company’s most famous ones.

The company saw Société Immobilière as an excellent investment opportunity. The property was “item 33” on the Heritage List, with a unique Neo-Renaissance architectural style. Moreover, it was located on Fouad Street, one of Alexandria’s oldest streets. The company bought it from its owner. When studying economic opportunities of the area, Sigma found that the city center lacked attractive and upscale restaurants; therefore, it decided to lease the ground floor to an investor. The investor then created what is now known as L-Passage to the residents of Alexandria which has Egyptian, Japanese, Italian, Lebanese and other cuisines all in one place. The investments in the area created a much more cosmopolitan city. The Al-Līthī Architectural Office designed the interior and exterior of the project. The place became a destination for many and managed to attract other commercial activities via redesigning the ground floor and leasing it.

Results and impact

When asked about L-Passage, Dr. Sāmaḥ said that the new uses Sigma added did not cause any harm to the building nor Fouad Street. However, experts disagree about the impact of the new development. One specialist explained that the private sector must operate within the laws and regulations of heritage preservation that explain how and what should be done upon reviving the building. It should not be left to the company to decide that. For example, there are banners and external design elements in L-Passage; this specialist believes that Sigma did not adequately consider the unique architectural style of the building.

Sustainability

The Sigma Group has been very successful in achieving social and economic sustainability. Through its real estate investment methodology, Abu Al-’Ulā said, Sigma makes all parties “partners” in its development. The new tenant is responsible for the design of the ground floor and presents the design to Sigma’s engineering department. When all parties are partners, this increases the chances of community sustainability as the new tenants, as well as residents, are connected to the activities and the place. Economic sustainability, on the other hand, is achieved through continuous financial returns resulting from leasing the property to an investor who carries out the agreed upon activity. The preservation of heritage, as Dr. Sāmaḥ explains, will not be achieved by turning heritage buildings into museums (meaning simply restoring the facades without considering the economic aspects or uses, as what happened in Cairo) because this intervention is not sustainable. Restored buildings will revert to their old conditions when there are no funds for future maintenance; thus, the building must remain self-sufficient financially. This self-sufficiency is maintained through the addition of appropriate uses of these buildings, thanks to the public-private partnership.2 As for environmental sustainability, there is currently no data on the impact of the added activities. However, the new developments have helped to preserve the urban and cultural environment of the city, enhancing the environmental sustainability of the initiative.

Replicability and future plans

Can the Sigma approach be replicated elsewhere and in the future? The company will not be able to own all the heritage buildings in Alexandria. More importantly, the community itself will not be able to rely entirely on the private sector to preserve the heritage of the city. There are, for example, some registered buildings where the private sector may not see an investment opportunity, as mentioned by Karim Mahmoud, the company’s commercial development manager. Should we leave those properties for demolition and vandalism? Two main points are important when considering the applicability of this experience:

1) To disseminate knowledge through public-private partnerships, the state must have a role in monitoring interventions. Abu Al-’Ulā pointed out that there are many private sector institutions that want to profit quickly, without any future vision. Therefore, projects need a strategic plan and support from the state. Moreover, as Ahmed Mostafa, creator of the Save Alexandria Initiative, pointed out, the state’s participation will ensure that the heritage center of Alexandria will not be subject to gentrification if the private sector becomes the sole player in conservation. He added that the private sector is generally profit-oriented. If there is a discrepancy between the financial return and the method of preservation, and there are no regulations, the company will favor profit, which may pose a threat to the heritage value of the building.

2) Dr. Tāha pointed out that in order to replicate the revival of the city center elsewhere, the building’s uses should be diverse and not exclusive to a particular social class. In other words, the very wealthy or the upper-middle class should not be the only targets of the investor.

Conclusion: Critical vision

In light of this, Sigma’s Real Estate Investment approach is more mature than the traditional investment approach. With the traditional investment approach, the multi-story residential building that replaces the heritage property will be just “another building” among thousands of buildings in the area. Thus in these cases, the return is be limited to direct and rapid profit from the sale of apartments. However, the reuse and revitalization of a heritage building demonstrates its architectural excellence and become a distinctive landmark. This increases the value of the property and the value of the wider area, thus becoming a catalyst for new development and investment in the area. In other words, those who invest in heritage see the economy in a broader way, and they are conscious of ripple effects.

The company’s business mechanisms are close to the Buy-Conserve-Operate (BCO) approach, which is a method public-private partnerships often use in heritage preservation. It lacks, however, the involvement of the public sector (the state) in terms of setting the standards of intervention, maintenance, and conservation methods. Given that the Ministry of Finance is currently working on increasing private sector participation in several sectors, why is urban heritage not one of them? When it comes to increasing private sector participation and cooperation with the public sector, the modalities and aspects of involvement may vary. The private sector might participate through ownership, operation, and management, while the public sector ensures that preservation takes place in accordance with regulations (somewhat similar to the Sigma approach). The private sector might be responsible for the funding part only while the public sector is responsible for all other aspects.

While some have jumped into criticism of banner designs, this is akin to climbing to the top of Maslow’s Pyramid of needs before making sure the base is established. Many heritage buildings are being demolished and vandalized, but Sigma has worked to invest in heritage properties and protect them from demolition, following a deliberate approach comprised of several phases. Of course, we should not overlook the method of intervention and design of the added activities, but at the same time, there must be some flexibility to suit the reality of implementation.

In conclusion, Sigma has emphasized that the preservation of heritage is not simply restoring a building, but also making it practical and adaptable through engaging activities for the community. To mainstream such a model, we need legislation that not only defines demolition sanctions and conservation methods, but also lays out what public-private partnerships to preserve heritage should look like in the future.

Relevant resources

Knecht, Eric. 2015. “Cover story-Growing pain.” American Chamber of Commerce in Egypt Business Monthly, May 2015. https://www.amcham.org.eg/publications/business-monthly/issues/233/May-2015/3284/growing-pain

MacDonald, Susan. 2011. “Leveraging heritage: Public-private, and third-sector partnerships for the conservation of the historic urban environment.” ICOMOS 17th General Assembly, 2011-11-27 / 2011-12-02, Paris, France.

Said, Lama, and Borg, Yomma. 2016. “Public Perception and Conservation: The case of Alexandria’s Built Heritage.” Heritage in Action: Making the Past in the Present, edited by Helaine Silverman, Emma Waterton and Steve Watson, 151-166). Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Sigma Properties. 2015. “Sigma Properties.” Accessed January 2017, from http://sigmaproperties.net/about.html

1. Solidere is the Lebanese company for the development of downtown Beirut, which was utterly destroyed after the civil war in Lebanon. Solidere was established as a joint-stock company with types of shares: one for the owners of assets in downtown Beirut before the demolition, and the other for new investors. The project has been criticized because the development has targeted the higher-class and the rich. Even some public venues gave private security companies the right choose who is allowed to enter that venue or who is not. That is, it turned into a manifestation of isolation and class replacement.

2. Researcher Susan MacDonald identified, in conference research in 2011, five forms of public-private partnership. These types are categorized according to the role played by the partner. These roles include design, implementation, operation, maintenance, and financing. Each type of partnership exchanges and the responsibility of the public and private sectors in assuming these tools varies.

Comments