Mīt `Uqba

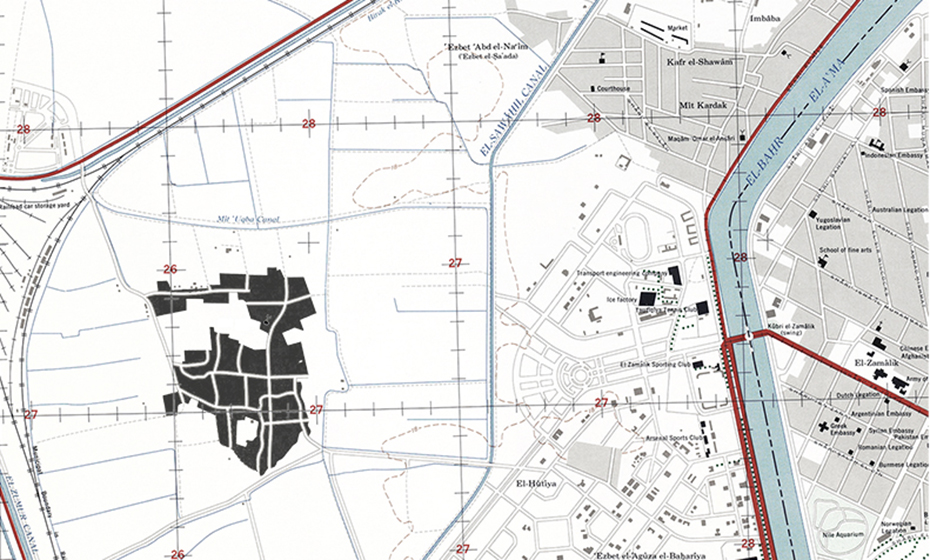

Every day, thousands of cars travel along the 26 July Axis, the “Miḥwar” link between the heart of Cairo and its outskirts, the sprawling satellite cities of 6th of October and Sheikh Zāyid. The Miḥwar then cuts through the area between Zamālik and Tirsāna sporting clubs from one side, and Lebanon Square and Mīt `Uqba from the other. Many see Mīt `Uqba as they pass over it or hear about it in the newspaper; they might consider it one of Gīza’s informal areas that has grown recently in flagrant defiance to the modern Muhandisīn neighborhood and its organized urbanism. What is not understood, however, is that they are crossing over one of the oldest urban communities in the Gīza Governorate, one which was established more than a century ago to manage the surrounding agricultural land. In short, Mīt `Uqba was never a ‘random’ or ‘informal’ area or a flaw in the existing urban order, but rather the original urban order itself which the Muhandisīn district gradually grew around. Muhandisīn itself was only established in the 1950s as an area of single-story villas, and grew rapidly in the early 1970s until Mīt `Uqba was completely surrounded by it.

Area: 460,800 square meters

Population: 96,000 (according to CAPMAS’ 2006 estimates)

The Story of Mīt `Uqba (Founding and Development)

Mīt `Uqba was originally a rural village, just like many other areas in the area of the Gīza governorate. Mīt `Uqba was surrounded by agricultural land until the first half of the twentieth century. The majority of these fertile areas, which grew wheat and corn, were transformed into high rise apartments and subdivided into an upscale residential area starting at the 1950s. Mīt `Uqba was at this time known as Minyit `Uqba, named after `Uqba bin `Amir bin `Abs al-Guhanī, one of the Companions of the Prophet Muḥammad and governor of Egypt during the reign of Mu’awiya bin Abi Sufyan. `Uqba lived in Cairo, died in the year 58 AH (677 CE) and was buried in Muqaṭṭam. During his reign, as stated in al-Maqrīzī’s description, he was given land by Mu’awiya totaling “one thousand arms by one thousand arms” (equivalent to roughly 55 hectares) for his benefit and to build a home for himself and his children.

Despite the substantial changes and successive uses that surrounded the neighborhood, Mīt `Uqba has nonetheless retained the unique architectural attributes of a village with narrow streets and abutting dwellings. The neighborhood has also retained the original street names honoring its prominent families and mayors who have served there; to this day many of the residents can still trace their lineage to these old families. Mīt `Uqba continued to hold on to this urban and social character and to its traditional management arrangements wherein the “`Umda”, or mayor, was in charge of the majority of village affairs, including maintaining order, security, and negotiating conflicts. The mayor also had the power to punish criminal acts at one point. In the 1960s, however, this has changed and the system of `Umdas was done away with, and Mīt `Uqba became party to the system of municipal administration of Gīza city according to national municipal divisions. Initially, it was part of the Imbāba district, but was later redistricted to become part of the `Agūza district which is still the case today. Gradually, the neighborhood was affected by the urbanization around it.

Beginning in the 1990s, Mīt `Uqba saw a series of changes in its urban and demographic composition, particularly after the collapse of several buildings in the 1992 earthquake. Subsequently, many people moved from the neighborhood to others like Muqaṭṭam or the former Imbāba Airport area. In 1999, a large portion of the neighborhood (250 by 40 meters) was demolished (taking with it over 400 apartments) in order to build the 26 July highway axis, connecting downtown Cairo with the 6th of October and Sheikh Zāyid satellite cities. The Miḥwar resulted in splitting the entire area in half. As a result, many of the residents–who were born and raised in the neighborhood–were forced to move to neighboring areas like Barāgīl or the Imbāba Airport.

The Place and its People

At first glance, the boundaries between Mīt `Uqba and neighboring areas like Muhandisīn are surprising. How did this tiny neighborhood with its adjacent buildings and narrow, winding streets come to be in the middle of the wide avenues and high-rises of Muhandisīn? This urban phenomenon cannot be explained without being aware of the nature of the social fabric and composition of the neighborhood. The families of Mīt `Uqba have deep histories and longstanding connections between them and they typically chose the village mayor, who at one time managed village affairs.

The Shāhid, Di`bis, Gūhar and other families in the area can trace their lineage to the beginning of the neighborhood and many of the streets are named after them. Due to the number of families and even greater number of mayors as time went on, there were a number of estates in the area whose locations are still known to the residents. One relevant example is the Shāhid Estate, whose original building still stands because of the family’s desire to maintain and renovate the old building from time to time. Despite the fact that this estate has not served its original purpose since the 1960s, the family remains protective of the building and keeps it open to the neighborhood for social events, funerals and weddings, all free of charge. Likewise, the Di`bis and Gūhar estates are still in their same traditional locations even though the original buildings were demolished. Both families were interested in building a new building in place of the old.

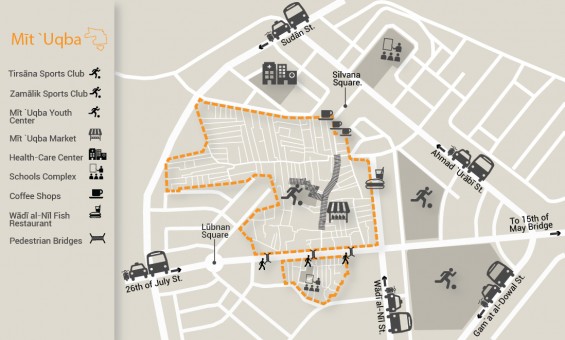

Another striking feature in the architecture of Mīt `Uqba is the 26th of July axis—mentioned above—which cuts the entire area in two. Residents have dubbed the southern, smaller area “Mīt `Uqba Island” and it is there that most of the neighborhood services, such as bakeries, the fire brigade and the school, can be found. The northern part is the larger of the two, and the more dynamic and densely populated; here one can find the youth center and the market. This territorial split has been negative for residents since they often have to cross this very busy thoroughfare on daily errands or to bring their children to school. For example, the Mīt `Uqba market has suffered economically since it used to serve all of Mīt `Uqba and the neighboring areas, including Muhandisīn. The market has come to play a much smaller role after the construction of the Miḥwar made it less accessible. Despite this, the Mīt `Uqba market remains vibrant and one of the most focal points in the neighborhood as vendors and shoppers still flock to it.

A quick survey of neighborhood architecture shows that most of the buildings are residential with some commercial usage on the ground floor. The streets of the neighborhood are full of life and in the evenings people come to sit and visit until late at night. At the edges of the neighborhood are several auto repair shops frequented by residents of neighboring areas. Along Wādī al-Nīl Street, which borders the neighborhood on the East, there are also many popular fish restaurants frequented by residents of Mīt `Uqba and Muhandisīn alike. Most of the other services inside the neighborhood are concentrated around the market and the youth center and along either side of the Miḥwar.

Nonetheless, the area lacks several basic services; particularly a health center or clinic. This led some people in the Mīt `Uqba Popular Committee to try to provide one by converting an unused office building on Sudan Street, which defines the northwest boundaries of the area. Indeed, their efforts were successful and the Mīt `Uqba Comprehensive Health Center opened in November, 2011. It is worth mentioning that there was a public health clinic in Mīt `Uqba, but the building was severely damaged and officials decided to demolish and rebuild it ten years ago. Residents however were shocked when upon rebuilding it was commissioned as a private hospital for children, whose services were too expensive for most of Mīt `Uqba’s residents, leaving them without any public health services.

Building heights in Mīt `Uqba vary greatly from those of the surrounding areas. Given the age of the neighborhood and its original rural character with narrow streets, the buildings are no more than four or five stories high, particularly in the neighborhood’s core. Although some of the very old single or two story stone masonry buildings still remain, such buildings are usually in a poor structural state due to prolonged humidity and groundwater undermining their foundations. Nonetheless, they distinguish the area’s unique architectural character unmatched in neighboring areas. The buildings located at the boundary of the area are largely modern buildings of roughly ten stories each.

Most of the land in Mīt `Uqba is privately owned by residents from the large prominent families who hold on to their land generation after generation. Additionally, there is some land owned by the Authority of Endowments (Awqaf). There is hardly any vacant land due to high occupancy rates and demand for construction and housing in the neighborhood. The vast majority of residents are the owners of their homes, although a small number rent under the old or new rent laws. Most of the residents work outside of the neighborhood except for a few workshop and shop owners.

Mīt `Uqba is provided with basic infrastructure networks and natural gas lines are currently being extended through the neighborhood (March 2013) and work on this has neared completion. However, the general situation for the remainder of the infrastructure—drinking water, sanitary sewer and electricity—is significantly degraded, much as in many similar areas where these networks are in constant need of repair. Public street lighting is not installed in the majority of neighborhood streets, prompting residents to install lighting on the facades of their homes to illuminate the streets. Additionally, the ground floor level in many houses, particularly older buildings, has sunk below street level as a result of repeated repaving causing ground water accumulation in these houses. And even despite this continued repaving, the roads remain in poor condition leading to problems for pedestrians and cars. Due to this situation, aggravated in the smaller streets, the Popular Committee of Mīt `Uqba decided to begin an initiative to repave streets with interlocking paving blocks using the limited resources of the district administration after their strenuous efforts to learn the details of this funding priority and secure these funds.

What is Important about Mīt `Uqba

Mīt `Uqba is distinguished by its central location and ease of access to and from the rest of the city. It sits near several different points of transit access to Cairo’s other districts, particularly after the construction of the Miḥwar, which placed the neighborhood along a major artery connecting the heart of Cairo to its extremities. The majority of transit options are located nearby, along Aḥmad `Urābī Street, Lebanon Square, and Sphinx Square. The low prices of rental housing in the area, likewise, make the neighborhood attractive to residents. Despite these distinguishing features, or perhaps because of them, increasing demand for housing in Mīt `Uqba has created substantial pressure on the urban environment as densities increased. This has led to rising real estate prices, leading many to sell older houses to be demolished and rebuilt as apartment buildings that place yet greater strain on the area’s public services and infrastructure. Nonetheless, this has not yet spun out of control and it is only a small percentage of owners who have sold in recent years, perhaps because—as noted above—the land and buildings are strongly connected to inherited family property.

There are strong social ties between residents; people know their neighbors whether they live on the same street or in the surrounding ones. Residents are aware of the history and origins of the area, including the younger generations. Streets, which form the social space, bring together young and old in their daily routines and social relations. These close social ties aided in producing and perpetuating many popular initiatives since the revolution. The Popular Committee of Mīt `Uqba, formed by a group of neighborhood young people should be considered one of the most prominent and successful of these initiatives. It has continued to provide services and undertake various activities and initiatives since the revolution, as opposed to many other popular committees—such as those from nearby Muhandisīn—which briefly came about in the security vacuum to protect homes and properties but did little else after that. Similarly, the residents, with the aid of the popular committee, have organized elected administrative councils from among the residents of each street in Mīt `Uqba to represent residents, propose initiatives for neighborhood development, and discuss various problems.

The Popular Committee of Mīt `Uqba played a major role in the development of the area since the Revolution

Architecturally, many of the old buildings remain intact and the neighborhood retains a distinct architectural style. This in particular distinguishes Mīt `Uqba from its surroundings, most of which originated in the 1950s. Mīt `Uqba is therefore one of the few areas in Greater Cairo that still retains its old buildings which were once at the fringes of the city, combining architectural vocabularies of the countryside (such as winding streets and mayoral estates) alongside Bandar (the urbanized city center) architecture and attempts to copy styles of wealthy neighborhoods. There are also multiple Maqāms in the area, dome-shaped shrines built for the righteous, which are popular with the residents of Mīt `Uqba even though they do not know when they were built or who occupies them. The transient visitor to such an area cannot easily take note of these unique features, unless they were to wander longer in the narrow back streets and alleys. Those buildings represent a rare architectural heritage, threatened to go extinct as a result of degradation, lack of maintenance, and rising groundwater.

What are the Problems of Mīt `Uqba

Like many other less fortunate neighborhoods of Greater Cairo, Mīt `Uqba experiences many problems such as the failure of authorities to maintain basic infrastructure networks or lack of a garbage collection system (despite the fact that residents pay fees with their electricity bills for this service) which leaves streets littered with uncollected garbage, particularly along the wall separating the neighborhood from the Miḥwar. The deterioration of the sewage network is also one of the biggest problems facing the area and usually manifests itself in the form of an overflow of sewage or groundwater seeping into some houses below street level. Unfortunately, this problem has yet to be dealt with in a proper, structural fashion due to the lack of available public funds. In addition, Mīt `Uqba as a whole suffers, like many other popular neighborhoods in Cairo, from stigmatization and the misrepresentation of the area as an informal or slum area full of criminal activity and is perceived as a threat to neighboring areas. This false stereotype has been perpetuated by the media and exploited by the government to deprive the area of basic services.

Streets are littered with uncollected garbage, particularly along the wall separating Mīt `Uqba from the Miḥwar

The area is witness to growing political struggles in the neighborhood between parties and candidates to the parliamentary and local council elections, whether before the revolution or since, due to the presence of many different political tendencies and prominent families competing for office to represent the area. Therefore, many political parties are keen to have a presence within the neighborhood to gain votes and sometimes this encourages elected parties to provide services to the area once they are in office. However, this electoral competition may also lead to conflict among political parties and local families without benefitting citizens.

Opportunities for Neighborhood Development

With an increase in political consciousness and the spread of a political culture where citizens are vocally claiming their rights, there are more opportunities to develop the neighborhood. It used to be that the only opportunity for development and increasing public services in the area was during the election cycle, when candidates competed to provide services to the neighborhood. Now, in contrast, there are constant popular efforts articulating the needs of residents and making demands on the government and other actors. The efforts of the Popular Committee of Mīt `Uqba is the most prominent of these initiatives and members of the committee have succeeded in communicating with administrative agencies to provide real services to people and draw official attention to the needs of the area, pushing the latter to take note and respond to the demands of residents.

The current political and social mobilization surrounding candidates for Parliament and Municipal Councils, and their attempts to win the support of the people of Mīt `Uqba due to their voting power and interest in public affairs, may be locally useful. However, with the presence of the popular committee as a means of popular pressure and claims-making, and the political awareness of citizens, this attention could be turned to push parties to contribute effectively to the development of the area through improving the performance of local administration. Moreover, the Mīt `Uqba Popular Committee looks beyond the limits of their neighborhood to other initiatives working in various areas of urban and social development across Greater Cairo, providing a great opportunity to connect and take advantage of other experiences.

With a bit more effort and awareness, the resources of Mīt `Uqba can be put to use to develop the area as a whole

Finally, Mīt `Uqba possesses a variety of resources, including its social and political mobilization, a network of firm and solid social relations, an economic significance, and a unique architectural character preserved in the historic buildings that serve as a social link against the attacks of high modernity. With only a bit more effort and more awareness, these resources can be put to use to develop the area as a whole and to serve residents and neighboring areas. For example, the market can be developed into an important node and point of attraction for the area because of its dynamism and low cost. Likewise, repairing and maintaining historic buildings presents another potential opportunity to highlight the value of existing architectural heritage in Mīt `Uqba.

Were you to imagine how Mīt `Uqba looks from an airplane, or have seen a map of it amongst its surrounding areas, you may have thought that Mīt `Uqba represented a “glitch” in the “order” of the upscale Muhandisīn neighborhood. However, Mīt `Uqba is the origin. It stands as an island that still holds architectural attributes of an era never to return, sitting in a sea of modernist urbanism that devoured the fertile land surrounding it. Mīt `Uqba is an “order” of a different kind that we have stopped trying to understand. We have tried for many years now to eradicate these other “orders” within our cities under the pretext of high modernity, stigmatizing these populations indiscriminately, without realizing their long history, and their generational efforts to maintain what they see as a small homeland for themselves.

Comments