`Izbit Khayrallah

When driving along the Ring Road between the Autostrad and the Maʿādī Corniche, westward towards al-Munīb, or towards New Cairo on the city’s eastern edge, you will notice the many billboards advertising this product or that television show. You may also notice people standing on the sidewalk of the road waiting for a microbus, and truck drivers unwinding from their long drive at one of the small roadside cafes. Beyond all these daily scenes, is one of the hidden areas of Cairo, an area that one might pass by daily without wondering: What is this area? What is its history? How are its people living? This area is `Izbit Khayrallah and it has a story filled with struggle and determination worthy of telling.

`IZBIT KHAYRALLAH IN NUMBERS

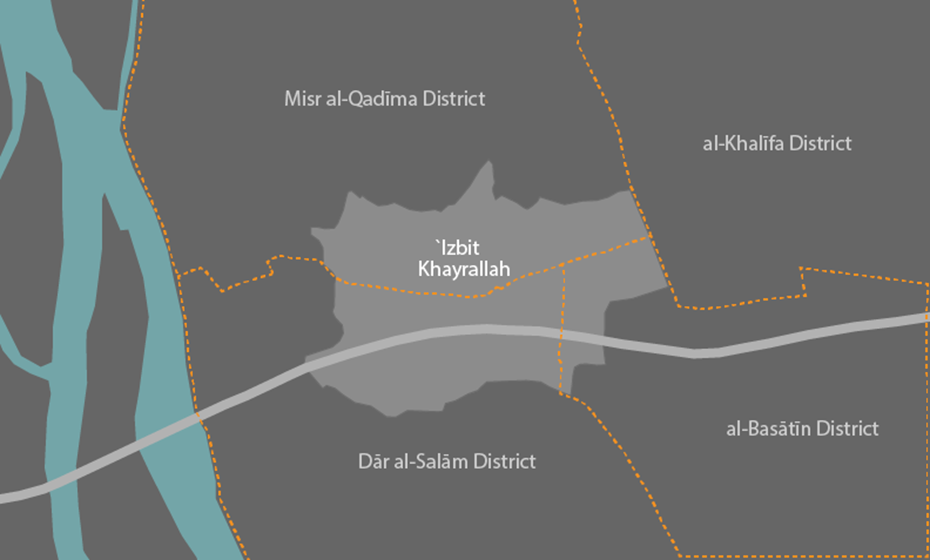

Governorate: Cairo

District: `Izbit Khayrallah falls under four different districts: Miṣr al-Qadīma (Old Cairo), Dār al-Salām, al-Basātīn, and al-Khalīfa

Area: 480 acres (2 km2)

Population: Approximately 650 thousand inhabitants according to the estimates of Peace and Plenty “Khayr wa Baraka” Association. CAPMAS has no exact figures exclusively for the area of `Izbit Khayrallah, but the population estimate for the whole district of Miṣr al-Qadīma (which contains a large portion of `Izbit Khayrallah’s area) in 2006 was only 250,000 inhabitants.

THE STORY OF `IZBIT KHAYRALLAH

Forty years ago, the area currently known as `Izbit Khayrallah was an empty rocky plateau north of Maʿādī. In the mid-1970s, poor migrants from Upper Egypt and Delta cities settled on this vacant land. There were no roads, infrastructure, or services. The migrants came to Cairo looking for work, but could not afford to buy or rent housing in the city, so they built their homes from the stones available on the site.

The name “Khayrallah” emerged in the early days of the settlement. Some say it is in reference to one of the first families that settled in the area. However, the Khayrallah family was not the primary settlers in the area. The Shalahba family, believed to be from a Bedouin tribe, had been living in the area even before the first migrants arrived. To this day, the Shalahba’s family guesthouse still stands surrounded by the family’s group of houses, in the southern tip of `Izbit Khayrallah.

The conflict about `Izbit Khayrallah land ownership started when President Anwar Sādāt issued an Executive Decree in the early 1970s allocating the land to the Maʿādī Company for Development and Reconstruction (MCDR) to build new housing units.1 This made the MCDR an invisible party to the conflict, with the real conflict between the residents and the Governorate of Cairo (GOC). Initially there were many confrontations between the government and the residents during the governorate’s many eviction attempts, but the residents were unwavering and stayed in the area since they could not afford renting or purchasing land to build another home somewhere else.

Early on, residents started organizing themselves to take legal action to ensure their land rights and to resist the state’s attempts to evict them and demolish their homes. The residents filed the first lawsuit in 1984 to claim their right to acquire the land underneath the homes they had constructed. The case dragged on for almost fifteen years and in 1999 a final verdict from the Supreme Administrative Court was issued in favor of the residents, rescinding the governorate’s executive Decree that prohibited the sale of the land to them. Essentially, this verdict made residents eligible to own the land by purchasing it from the governorate. The 1999 verdict has yet to be implemented as the residents still do not own their land, nonetheless the verdict proved the legitimacy of the residents’ land rights and the fear of being evicted and displaced is now behind them. (more about the case of land tenure)

During these years residents started another struggle to introduce essential infrastructure and services, such as water, electricity and sanitation. Residents started to raise funds and through collective action installed water, electricity and sanitation connections to the main network. Residents coordinated with different entities like the governorate, water, electricity, and sanitation companies, and sometimes with the Supreme Council of Antiquities to issue permits to drill in some areas, and later with the district to request street paving and lighting. At the same time, civil society organizations started developing an interest in the area, and collaborated with residents to provide some essential services. Parliamentary candidates as well, in attempts to gain residents’ votes, used their influence with officials and politicians to facilitate the introduction of some services and facilities.

After the 1992 earthquake, population density increased in `Izbit Khayrallah, as many people, whose houses had been destroyed or critically damaged had to search for affordable housing in neighboring areas. The state could not provide enough alternative housing to those in need and thus they turned to the less expensive informal areas to find affordable housing.

In the late 1990s, the Ring Road was constructed and consequently split `Izbit Khayrallah into two: the northern part which comprises the majority of its area and the southern part which includes Istabl ʿAntar. Despite this division, the Ring Road increased real estate values in the area. The state compensated residents whose homes were demolished during the road construction. Residents who did not wish to relocate outside the area purchased new properties inside `Izbit Khayrallah. The completion of the Ring Road, one of Cairo’s primary transportation corridors, increased accessibility and connected `Izbit Khayrallah to other regions of the city. These factors were incentives for residents to improve the quality of construction to further increase the real estate value of their properties. (Listen to the views of some of `Izbit Khayrallah residents)

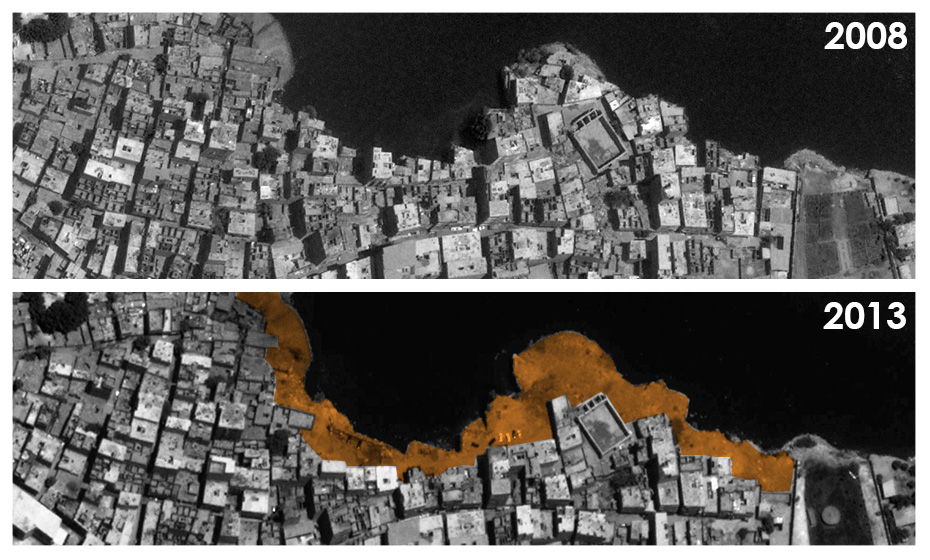

In 2008, after the rockslide in the Duwayqa district caused the death of more than 100 residents, the GOC formed a technical committee to examine similar areas in `Izbit Khayrallah and Istabl `Antar to avoid another tragedy. The committee indicated that a number of houses on the plateau’s edges were unsafe for habitation and strongly recommended eviction and transferring residents to alternative housing in 6th of October City. A number of other problems appeared during the relocation process as a result of the refusal of some residents to be evicted, not providing alternative housing to all those affected, the lack of an accurate record of all beneficiaries, and the desire of some who were unaffected by eviction to abuse the system to receive a housing unit.

Today `Izbit Khayrallah has a very high population density and it continues to attract people looking for an affordable home close to the urban center.

The areas which were removed based on the recommendations of the technical committee that was formed to assess the vulnerable areas in `Izbit Khayrallah 3

THE PLACE AND THE PEOPLE

According to field studies conducted by Peace and Plenty Association, the population of `Izbit Khayrallah is estimated to be close to 650,000 living on approximately 480 acres (2 km2). However, residents estimate the population to be closer to one million. Most residents are working class, and some have found jobs inside `Izbit Khayrallah while others travel daily to other districts in Cairo. Because land ownership issues are not yet resolved, landlords pay the governorate 7% of the land’s value annually for the use of the land, since it is considered state-owned land. The value of the land is determined by the GOC to be 200 EGP per square meter, which sets the annual land use rate at 14 EGP per square meter. On the other hand, rents range from 300 to 500 EGP per month for new lease agreements, as indicated by the residents.

Most buildings are residential with commercial activities on the ground level. There are also many small workshops across the area, such as marble, foundry, and mechanics workshops. The most important and widespread craft is the timber industry, particularly wood boards, known in the markets as “`Izba wood boards.” There are about 170 wood board workshops in `Izbit Khayrallah, between small and medium scale workshops, some of which have been in operation for 25 years. There are also workshops that recycle old wood.

WHAT IS IMPORTANT IN `IZBIT KHAYRALLAH?

Social cohesion and cooperation are two of the most important characteristics of the area’s residents, perhaps due to their experience in overcoming communal challenges. As a community, they have responded to the government’s eviction attempts, they have fought for their right to own their property, and worked to bring infrastructure and public services to their community. According to the residents of `Izbit Khayrallah, many of them are educated.

Contrary to the stereotypical perception of informal area residents, employees and the self-employed constitute a sizeable percentage of `Izbit Khayrallah’s residents including engineers, doctors, lawyers and craftsmen, while others are workers or workshop owners. This social, cultural, and economic diversity contributed to the different development efforts.

The Khayrallah Lawyers Association for Rights and Liberties which was established in 2011 right after the revolution includes many young lawyers interested in public issues and defending the rights of the residents. They have taken it upon themselves to continue the land ownership lawsuit case that began nearly 40 years ago. There are also more than 20 registered NGOs working in `Izbit Khayrallah, such as the Local Community Development Association in Abū Bakr al-Siddīq Mosque, Peace and Plenty Association, Tawasol, and many others. A few years ago, eight community organizations collaborated to establish Iʿmār Khayrallah Association to coordinate between different development efforts.

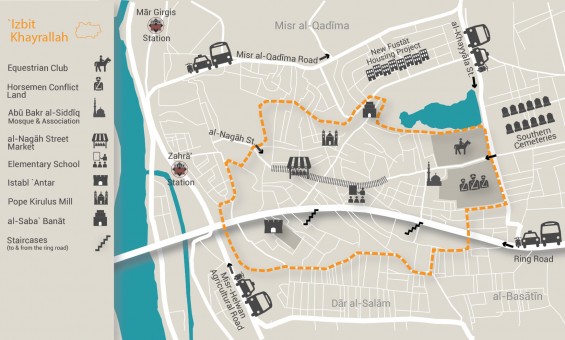

`Izbit Khayrallah is in a prime location. It is bordered by Maʿādī, al-Basātīn and cemeteries to the south, al-Fusṭāṭ and Old Cairo to the north, Autostrad, `Izbit al-Naṣr and more cemeteries to the east, and Dār al-Salām to the west, beyond which lies the Nile. It lies on an elevated plateau, and as a result most rooftops in the area enjoy a view of the Citadel and Pyramids, or even the Nile from the western edges. The area is also directly connected to, or in close proximity to other major road axes, such as the Ring Road.

`Izbit Khayrallah is close to several historical sites and touristic attractions, such as `Ayn al-Ṣīra, the excavations of al-Fusṭāṭ City, the Churches of Old Cairo, the pottery centers, and the Civilization Museum, most of which are concentrated in al-Fusṭāṭ district. However, what really distinguishes `Izbit Khayrallah and is unknown to many, are its historical sites and attractions dating back to the Coptic and Islamic eras. Unfortunately, these sites do not receive adequate attention from the governmental authorities and suffer from neglect, inappropriate use, trespassing, and the absence of any publicity or promotion, despite being in the heart of Cairo. This could be related to the fact that these sites are in what the authorities consider “slum areas” or ‘ashwa’iyyāt that some assume could pose a threat to visitors.

One of the most important of these sites is the Muhammad `Ali Gabakhānā (“Gabhakhānā” in Turkish), commonly known as Istabl `Antar. It is an armory after which the southern area is named. Istabl `Antar is a large armory, some 180 meters high and has a large courtyard. The armory was built by Mohamed Ali in 1829 AD/1245 AH as a replacement to the armory in the Citadel which twice caught fire, first in 1819 and again in 1823, significantly damaging the neighboring Gawhara Palace. Muhammad `Ali ordered its construction in Zahrā` Miṣr al-Qadīma area, far removed from the Citadel and other populated areas. The armory included four towers and a military hospital. Despite its historic status as a registered monument2, it is used today as a garbage dump. The space could potentially provide sorely-needed public space in the heart of the community and be utilized for cultural activities and public services, though the antiquities authorities rarely concur with such ideas from local residents; rather they are far more interested in the needs of tourists.

The northern region of `Izbit Khayrallah is home to another important historic landmark: Qibāb al-Sabaʿ Banāt (Domes of the Seven Girls), which dates back to the Fatimid era. According to historical resources, its name is al-Qibāb al-Sabʿ (Seven Domes). Historical resources narrate that the Fatimid Caliph, al-Ḥakim bi-Amr Allah killed several members of Minister al-Ḥussayn bin `Ali al-Maghrabī’s family after fleeing Egypt. When he tried to reconcile with the minister, the Caliph built six domes on their graves. Other sources suggest that the domes were built after the era of that Caliph. In later years, an unknown person built another dome nearby, thus the area was called the Seven Domes. Currently there are only four domes remaining, in addition to the excavations of the foundations of two others. All the domes are in close proximity to each other, and the seventh dome that was probably built after the other six, has been lost altogether. Like the armory, these domes suffer from neglect and lack of use, and many Cairenes are not even aware of them.

Qibāb al-Sabaʿ Banāt (Domes of the Seven Girls); one of the neglected historic sites in `Izbit Khayrallah. Dates back to the Fatimid era.

One of the oldest and most valuable sites adjacent to the border of `Izbit Khayrallah at the southeastern edge is the Aḥmad Ibn Ṭūlūn Aqueduct, which is also subjected to extreme damage and neglect. The aqueduct dates back to 870 AD/ 256 AH and is known locally as Magra al-Imām (the Imām’s Aqueduct). It is believed that it was built by Sa`īd bin Kātib al-Farghāni, a Coptic engineer who also built the famous Aḥmad Ibn Ṭūlūn Mosque, on commission from Aḥmad Ibn Ṭūlūn (the founder of the Ṭūlūnid era). The facility was built to bring in large amounts of water from the Nile to the newly constructed city: al-Qaṭaʾiʿ. All that is left of this structure is the Ma’khaz Tower, built of red bricks, inside which is an open empty well, known as Bīr Um al-Sulṭān (the Sulṭan’s Mother’s Well), with adjoining rooms covered by domes. The aqueduct extends to al-Qaṭaʾiʿ through an arched wall similar to the Magra al-`Uyūn wall in Old Cairo.

Despite its historical significance, the Aḥmad Ibn Ṭūlūn Aqueduct has deteriorated severely and is on the verge of collapse. Tons of garbage are now piled against the Aqueduct’s wall threatening its structural stability. Microbus drivers collected money to remove the garbage once, but unfortunately, a large part of the wall was removed as well during this process due to ignorance and absence of supervision. Although authorities have made attempts to remove the garbage, it persists, and several fires have erupted, exposing the wall to more danger. As for the well, someone turned it into a fruit stall and a kiosk was built in front of it preventing garbage disposal (and burning) at the well’s entry.

`Izbit Khayrallah is also home to Coptic monuments, such as al-Ṭaḥūna Church (the Windmill Church), which includes a historical windmill where Pope Kerlis VI, then known as Reverend Mīnā the Hermit, lived and worshiped for six years from 1936 to 1942. The windmill was restored and is currently inside the church. The mill is a cylindrical limestone building, 6 meters high and 3 meters in diameter. The area was previously known as the Tall al-Tawāḥīn (the Hill of the Windmills), as fifty windmills were built in the area during the French Campaign in Egypt (1798-1801 AD). This windmill is in good condition, as it is under the care of the church and is visited by congregants as a religious monument.

What are the Problems of `Izbit Khayrallah?

The absence of adequate potable water and sanitation networks are two of the most crucial problems facing residents of `Izbit Khayrallah. In 2007, the Ministry of Housing allocated 100 million EGP to create potable water and sanitation networks in the area, with the sanitation project alone estimated to have cost 70 million EGP. By 2010, 70% of the sanitation network was connected according to estimates of the Cairo Governorate, but in reality, sanitation networks are not complete to this day (June 2013). Accidents associated with the project claimed the lives of some of the residents. In 2012, one of the sewage pipes exploded, flooding parts of the area. As a result, sewage mixed with the potable water supply, making the lives of the residents very difficult. In addition to the regular problems of sewage networks in Egypt and especially in informal areas, the rocky terrain on which `Izbit Khayrallah is built forms another challenge, and makes it difficult to drill deep enough for pipe installations. As such, most of the networks are connected at shallow depths, lowering their performance and making them prone to damage. Drilling at great depth requires expensive special equipment that neither the residents nor the government can afford. Unconventional technical solutions are needed to deal with this problem.

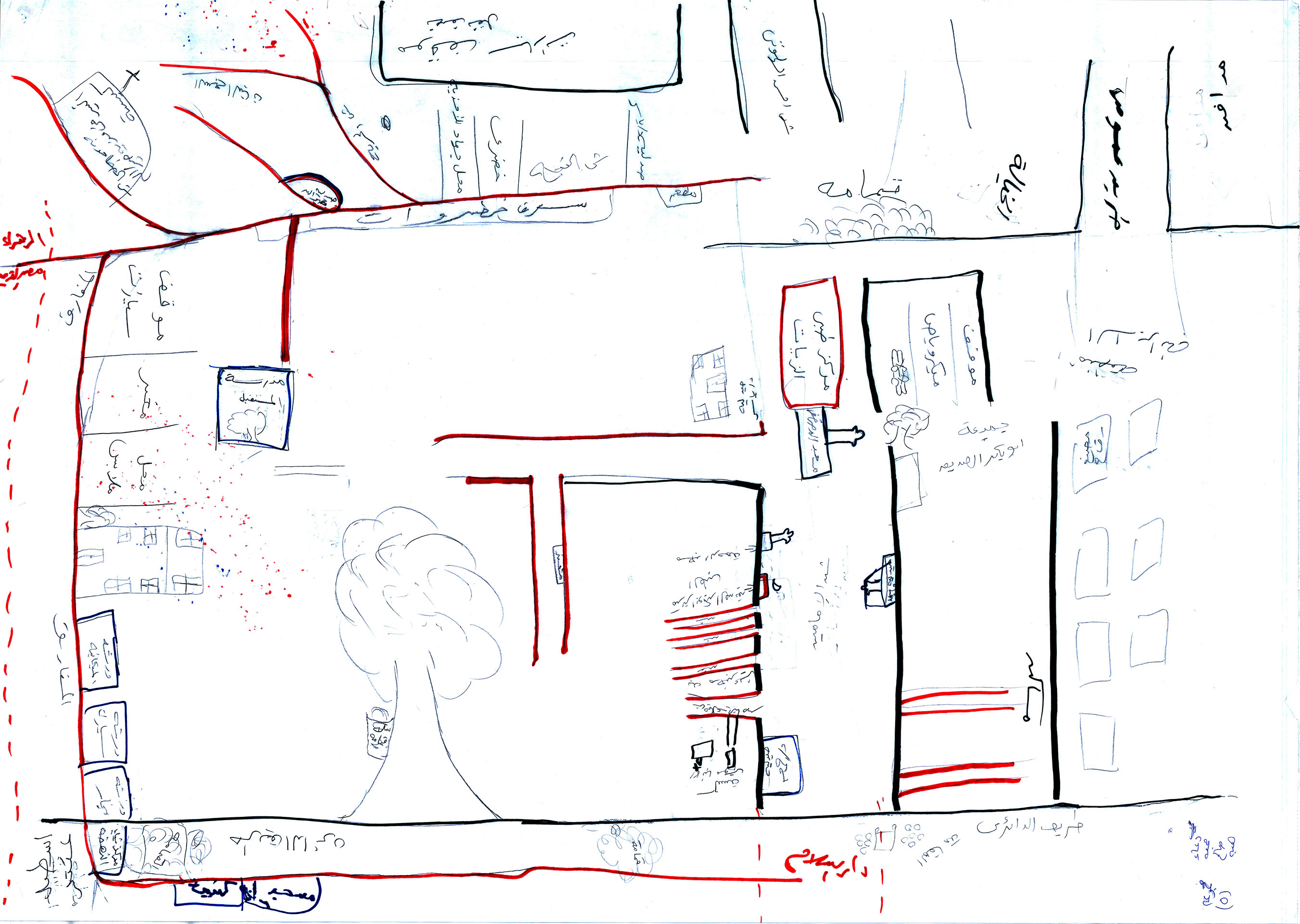

The area suffers from poor street conditions, which relates to repeated drilling for infrastructure networks and sanitation overflow. Even the paved streets are rapidly deteriorating due to these recurring problems. There is no street lighting; and although some residents provide exterior lighting at the facades of their houses, many areas are still completely dark at night. Streets are almost completely void of trees and residents expressed their desire for green space. (Listen to clips from the community workshop with `Izba residents)

Illustration showing trees in the streets of `Izbit Khayrallah. The sketch was drawn by residents of the area during the community workshop.

One of the problems facing the residents is the poor accessibility of the area despite its central location and proximity to main traffic arteries. This forces residents to rely on rickshaws to travel to the closest microbus or metro station which doubles the time, effort, and cost, especially for those who have to commute daily. Although the Ring Road runs through the middle of `Izbit Khayrallah, the government did not create an exit ramp or even pedestrian access to serve the community. As with all other occasions when their needs were ignored by the government, the community took matters into their own hands and built a staircase to access microbus routes on the Ring Road. And despite that this poses the threat of traffic accidents (particularly for young children and the elderly crossing these roads and bus routes), they were able to find decent solutions and built a pedestrian staircase and organized informal microbus stops, known to residents and drivers alike.

Garbage collection, or lack thereof, is creating a burden on the area’s quality of life. The responsible government agencies are not active and garbage continues to accumulate in the streets until residents burn it themselves or dump it on the Ring Road so that officials are forced to remove it to avoid traffic problems. A local NGO’s pilot program attempted to find a solution for the garbage problem by signing an agreement with the Ministry of Environment and the Cairo governorate in March 2008. However, this project is subject to debate between the inhabitants as they claim it only served a limited area and not the whole area of `Izbit Khayrallah.

`Izbit Khayrallah is known for its carpentry, wood, and marble workshops and although it is a point of pride for residents, and these workshops employ many workers and craftsmen from the area and from other districts, workplace safety measures are rare. This not only affects workers but also the residents since there are many flammable materials in these workshops and frequent fires erupt causing damage to the workshops themselves and nearby residences. Further, these workshops generate a great deal of waste exacerbating the garbage problem mentioned above.

Wood workshops are widespread in `Izbit Khayrallah, as it is one of the important and widespread crafts in the area.

Despite its high population density, its public services and facilities do not match other districts with far lower population densities. As mentioned earlier, `Izbit Khayrallah is deprived of all public services and there is no space available to build public buildings, except for a large vacant area (about 37 acres) on the east, owned by the governorate. In 1995 the governorate issued a decree to allocate 3,600 square meters of land to build a school and 6,000 square meters for a youth center. However, according to residents, the Mounted Police Department (al-Khayyāla) of the Ministry of Interior took over the land and obstructed the implementation of the decree. In 2005, the Ministry of Interior built a wall around the land to prevent ‘intruders’ from trespassing or settling on the property. The residents filed numerous complaints to the Governor, the Attorney General, and even to the President to no avail. The conflict is ongoing between the Ministry of Interior and the Cairo Governorate, yet the residents, deprived of the basic services entitled to them by law, are paying the price.

The residents of `Izbit Khayrallah were hoping that this 37 acres vacant plot will be used by the governorate to build facilities for serving the area. However, the ministry of interior took over the land.

Many of the problems facing `Izbit Khayrallah are related to its administrative and geographic boundaries. Despite being a homogeneous urban area which can be clearly distinguished on the map as an independent agglomeration, it falls within four different administrative districts. The area north of al-Nagāḥ Street falls within the Old Cairo district, the south is largely part of Dar Al-Salam district, a small eastern part is within al-Basātīn district, and its main entrance, a small part of al-Nagāḥ Street, falls under the jurisdiction of the district al-Khalīfa.

These divisions worsen and complicate local service provision, however minimal and inadequate it may be. Furthermore, it is nearly impossible to hold responsible parties accountable between the districts and inefficiencies abound. The consequent dependence of services such as police stations and prosecutors across four administrative districts confuses residents, especially when requesting official papers and national ID cards. Most importantly, this means there is no independent, dedicated budget to provide services to the area. Usually, the already limited resources allocated to these districts are directed to serve the areas which the officials consider more important than `Izbit Khayrallah. This financial marginalization prompted residents to file several requests to create an independent administrative district for `Izbit Khayrallah.

Despite being a homogeneous urban area which can be clearly distinguished on the map as an independent agglomeration, `Izbit Khayrallah falls within four different administrative districts.

Opportunities for Neighborhood Development

Today, `Izbit Khayrallah is an integrated community where most basic services are available due to the efforts of its residents. However, self-help efforts can only go so far and the community cannot self-finance all their needs especially with its growing population. It is the government’s duty to provide public services to residents as it does in other districts. Despite this hindrance, there are many advantages that can push forward development in the area, such as the numerous active NGOs and civil society organizations run by local leaders who are passionate about public wellbeing. This public service spirit is a long and prized tradition in the area and can be transformed, with good coordination and collaboration, into public pressure on the government agencies to pay attention to the area and cooperate with the community according to their own priorities.

Improving accessibility to the area and linking it to the surrounding road networks is of high importance, as well as public transportation. Infrastructure needs upgrading, the roads need paving, and garbage collection needs to occur regularly. There is much to be said about public services, but first among many priorities is that the government should resolve the dispute over the Governorate land currently occupied by the Ministry of Interior. Solving this conflict will allow the Governorate to develop the land to provide some of the needed public services to the community. Lately, there have been some initiatives geared toward developing the residential buildings, which attracted the attention of the “Paint Cairo” Initiative” spearheaded by Takween Integrated Community Development in 2011. In partnership with the community, Paint Cairo upgraded and painted a number of buildings facing the Ring Road using lime as an environmentally friendly material. The results of this initiative attracted more associations to repeat the project. For example, in 2013, Catholic Relief Services painted another series of buildings on the Ring Road.

Two key aspects remain that must be addressed for a more comprehensive development of the community: the first is the industrial base and craft presence in `Izbit Khayrallah that requires economic development through funding small and medium-sized businesses in the marble, carpentry and wood board industries. These businesses face the same problems that most informal economy industries do: lack of investment and development opportunities, no minimum social insurance or workplace safety regulations for workers, and problems with tax authorities and administrative corruption. Small and medium-sized businesses face all of these setbacks despite the informal economy’s significant contributions to the national economy and providing millions of jobs to citizens in many areas across the country.

Historical and cultural assets are another factor that can be utilized for comprehensive community development. The purpose is not to turn the area into a conventional tourist attraction, bussing in thousands of tourists, building walls around the monuments and filling the area with Tourist Police to limit the movement of the community so the tourists do not have to witness their sad reality. What is needed is a different approach, one that develops the monuments in collaboration with the community. This could be an adaptive reuse of some of these monuments (e.g. al-Gabakhānā and Um al-Sulṭan’s Well) to provide services and activities that can serve the residents. The government should consult with the community and support them financially and technically to establish services related to potential visitors and tourists and to encourage local tourism so that Cairenes and Egyptians across the country, who would generally go about their life without setting foot in `Izbit Khayrallah, would be interested in learning more about the parts of history landmarked there. The initiative should promote responsible cultural tourism so that visitors can interact with the community without barriers at cafes and restaurants and not just learn about history but also see how a large segment of Egyptians live.

`Izbit Khayrallah, as one of its residents said, is “a long story filled with struggle.” Over generations, the community turned it from an uninhabited desert to a vibrant place filled with life and value. Its residents bore the burden of the harshness of the environment, discrimination and state negligence, and society’s negative perception of the area, until `Izbit Khayrallah became what it is today. When will the time come when the state recognizes these residents and their strong community, and other communities like theirs, as full-fledged citizens with rights equal to the rest of the city’s residents? When will the state acknowledge its obligations towards them?

Related Readings

Environmental Voices: Of biohazards, 1100 year old monuments and participatory planning

Destruction Alert: Ibn Ṭūlūn Aqueduct in Basātīn

1. Republican decrees number 1197 in 1972 and number 1420 in 1974.↩

2. The registered monument is a building which is granted a special protective status by the Ministry of Antiquities↩

3. Source: Amnesty International Ltd↩

Featured Image source: AKDN, used with permission.

Comments