What Egyptians go through to find pure drinking water!

“I know a thing or two about the international distribution of Coca-Cola, and I am also aware of the habit of Egyptians (unlike more civilized nations) to drink water right out of the tap. All of which made me wonder if there is a link between the return of Coca-Cola to Egypt and the fact that our tap water has acquired a darker shade than usual.

On closer examination of this issue, I realized that deterioration in our drinking water preceded the return of Coca-Cola to our market by years. Through further examination, I discovered that tap water used to be, as of the 1960s, the main source of drinking water for this nation. Then the government introduced a policy of diversification and that’s when imported mineral water made its debut. Almost simultaneously, I found out, the tap water went through a change.“

Son’allah Ibrahim, Al-Lagnah (The Committee), 1981

In 2007, an uprising that can be termed “the Revolution of the Thirsty” broke out. It was one of the most astounding popular protests in Mubarak’s time, and one the likes of which this country hadn’t seen since the 1977 protests. The inhabitants of Burg Al- Burullus, a village in Kafr Al-Sheikh Governorate, cut off the coastal road in protest against the shortage of water in their village, a shortage that forced them to drink polluted water, a shortage they had complained about to officials to no avail.

The action by the Burg Al-Burullus inhabitants was one among several protests that have prevailed across the country, most of which focused on the daily needs of millions of Egyptians. Protests like this persisted for years, spread across the country like a chain reaction, until eventually the revolution of 25 January 2011 was sparked. The central demand of this revolution, which ended Mubarak’s rule, was social justice.

Drinking water is at the heart of social justice.

The Egyptian government made undeniable achievements in this regard, especially between 1990 and 2010, when the proportion of households connected to the drinking water network increased from 89% to 100% in urban areas and from 39% to 93% in rural areas. However, this achievement was one of quantity rather than quality. Government officials gauged their success in terms of the network’s reach and the number of households it served, not the quality of the water provided.

The issue of drinking water still makes the headlines from time to time. In the media, one often comes across headlines announcing, for example: “A woman in Burg Al-Burullus was run over by a water truck as a crowd of women struggled to fill containers with water,”1 or “4,000 poisoned after drinking polluted water in the village of Sansaft in Monūfiyya,”2 or “The village of Sarw near Damietta declared it would secede from the governorate to avoid Sansaft’s fate.”3 The issue of water quality is not confined to the countryside alone, but affects Cairo and its suburbs, as well as other cities. The inhabitants of Saft Al-Laban, a village in Gizah, picketed and then occupied the governorate’s administrative building in 20124 to protest water shortages that lasted for the entire summer, including the holy month of Ramadan. While in control of the governorate’s building, the inhabitants of Saft Al-Laban took turns using its toilets and showers.

What is the nature of the problem? And why is there such a gap between the government’s achievements and this painful reality?

Water treatment stations in Egypt are all run by the Holding Company for Drinking Water and Sewage Disposal (HCDWSD). The water these stations use comes from three main sources: the Nile and its canals (86%), artesian wells (14%), and desalination (negligible so far). After the water is purified, HCDWSD pumps it into its networks of pipes and delivers it to the end users. This system leaves much to be desired.

First, the Nile and irrigation canals have become so polluted that the purification stations are no longer capable of removing the entire range of pollutants and toxic substances from the water, which means that some harmful residues are left in drinking water. The conventional methods used to this day to purify water are not designed to remove industrial pollutants. The total of industrial pollutants in Egypt is estimated 4. 5 million tons per year, of which 50,000 tons are toxic. In addition, some sewage stations pump their refuse straight into the canals. And ordinary people often dump garbage and dead animals into the same canals from which the purification stations draw water for treatment.

Secondly, underground water is known for its high salinity, and is often polluted through mixing with sewage, industrial waste, and drainage water. According to the Central Authority for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS), in 2011 half of Egypt’s households were not connected to the sewage systems. The percentage was much higher in rural than in urban areas. Households not connected to public sewage systems use septic tanks to dispense of their liquid refuse. These septic tanks often leak into the ground thus polluting underground water. Water sources available to government-run water treatment stations are, therefore, often polluted with sewage. For lack of other options, some citizens end up drinking untreated underground water, which they draw by Hand pumps.

Thirdly, even the luckiest of households, those that are connected to water networks, often suffer from irregular supply and weak water pressure. The water network itself is worn out. Fifty percent of the water is lost through leakage. What is worse is that the worn-out pipes allow the sewage water to mix with drinking water during the distribution process. As a result, households, especially those using pumps to improve their water supply from the system, have a substantial chance of drawing polluted water.

Finally, the responsibility for checking the water quality in Egypt is divided between the Regulation Agency for Drinking Water, Sewage, and Consumer Protection (RADWSC) and the Ministry of Health. Both agencies are underfunded and the overlap in their responsibilities hampers their work. As a result of the poor infrastructure and inefficiency, nearly 56% of rural inhabitants are deprived of their right to a regular supply of clean drinking water, which exposes them to detrimental health hazards such as renal failure, cancer, and high child mortality. Realizing the state’s inability to address this multi-faceted problem, citizens began to search for solutions on their own. This case study focuses on the manner in which citizens in one Egyptian village addressed the issue. The initiative is fraught with questions regarding legality, ownership, the right to water, and the state’s policies, but it is relevant and worthy of documentation and discussion.

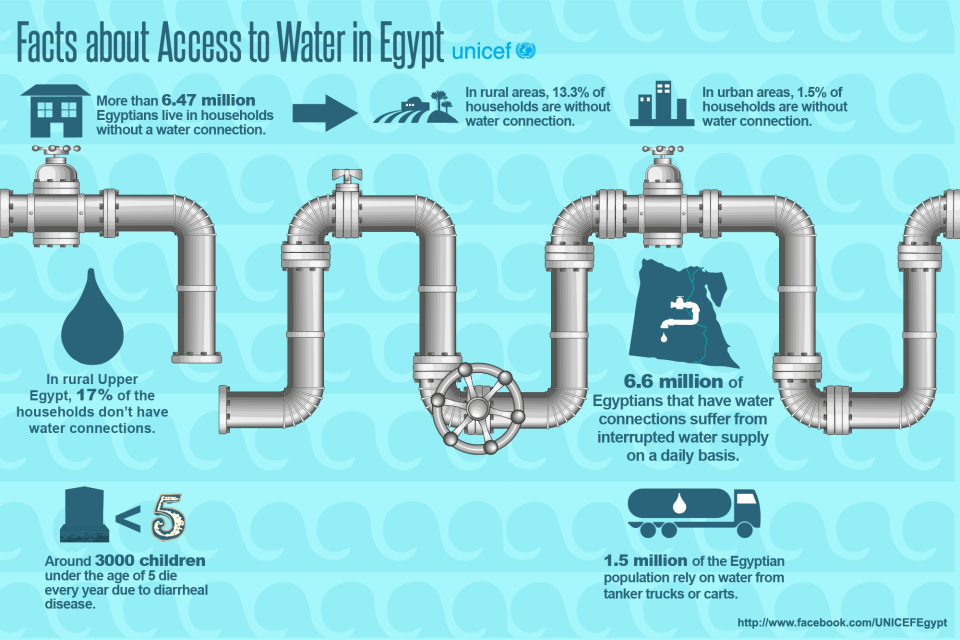

Facts About Access To Water in Egypt. Shared with public on UNICEF Egypt facebook page.

Situation Before

The village in which the initiative took place is home to 100,000 people who, like many other inhabitants of Egyptian villages, had a problem with drinking water.5 Despite the diversity of social and economic backgrounds among the inhabitants, they all agreed that clean drinking water was a priority. The water that reached the village through the government pipes was of poor quality, although it may have been clean at the source before being pumped into the outdated and leaky distribution system.

On account of the low pressure of water, the poor condition of the water pipes, and the consequent blending of drinking water with sewage, tap water in this village posed a real threat to the health of the inhabitants. They decided that if they invested more of their resources in clean water, their health and well-being would improve. Some of the poorer inhabitants resigned themselves to the situation and continued to drink water from the intermittent supply that comes through their taps for a few hours just before dawn. Other inhabitants installed Hand pumps into their yards or bought water from water trucks that transported water from less polluted sources.

The affluent people purchased home filtering devices costing up to 1,000 EGP and installed these at home. The filters are costly to operate as they require replacement every month at a cost of 100 EGP. The devices are hard to maintain, and the outcome is less than satisfactory as some pollutants still passed through the filters. Another part of the population resorted to an even more expensive solution, which is to buy bottled water for their domestic use. One liter of bottled water costs approximately 2 EGP. Some also began buying purified water from privately-run water treatment stations that are becoming more common in Egypt’s countryside.

Idea and implementation

In the absence of government action on the problem, the inhabitants decided to act. In 2012, one of the inhabitants started a for-profit water purification unit which he sold in jerry cans. He wasn’t the first one to start such a business. Before him, ten other private water treatment stations started production, the earliest of which was in 2007. The same thing was happening in other governorates. The eleven stations were all competing to provide the village with service.

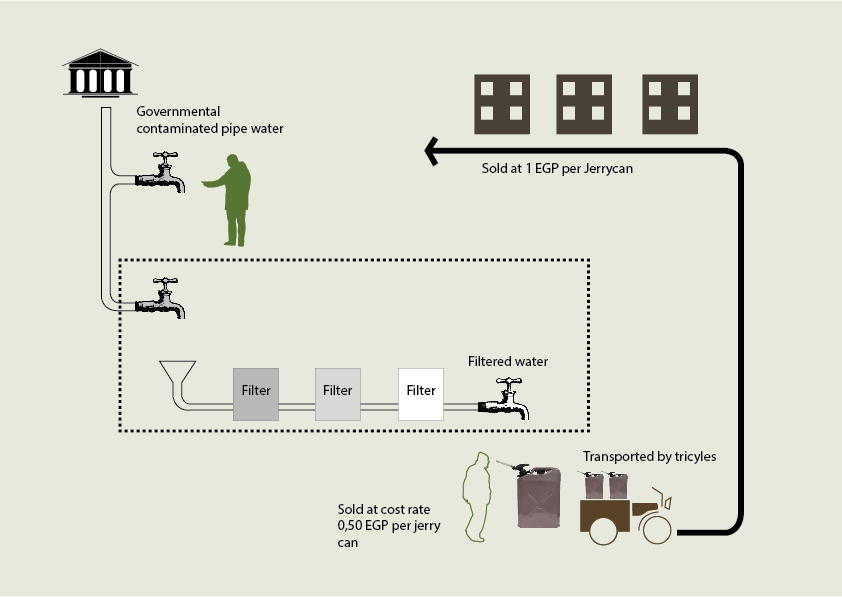

The idea of the project was simple. The owner of the project rented a small shop containing a source of water and electricity. Then he bought filtering devices to purify water from a specialized company and installed these in the shop. The activity of a private water treatment station is remarkably similar to that of larger public stations. The main difference is that the public water stations draw water at the source from the Nile or the canals and wells, whereas the private station draws water from the tap, water that had at some point been treated at a public station but became polluted once again during the delivery through the government’s outdated network of pipes.

The water is first stored in an initial tank to allow sediments to settle. Then the water is run through a variety of filters to remove sediments and any alteration in taste or smell. The water is then subjected to reverse osmosis, to clean it from salts and other minerals and exposed to ultra-violet rays to kill the bacteria. Then salt calibration is conducted, a process in which natural salts are restored to the water. This is because the treated water, right up to this point, had lost most of its mineral content during the purification process, and salt-free water can cause health problems.

After the purification, water is stored in special tanks and then sold to the public in 12-liter jerry cans. The operation uses two tricycles for delivery, each with a capacity to carry up to 40 jerry cans. When the jerry cans are empty, the station collects, cleans, and refills them. The station produces about 8,000 liters per week, enough to fill about 640 jerry cans. Customers can buy the jerry cans at the station or have them delivered at home.

The station is a for-profit private operation that charges its customers for clean water that is suitable for drinking and cooking, at a relatively reasonable price, compared to the other available alternatives. It also takes health precautions, such as monitoring the minerals in the water and sending samples for analysis in scientific labs. The station is serviced monthly by agents of a company which provides the filtering equipment. The filters and other spare parts are changed regularly as a result.

The owner, who studied commerce at college, had no previous experience in the field. He overcame this disadvantage by receiving training at the company that supplied him with the equipment. Before starting the project, the owner signed a contract with the company and asked it to estimate the equipment he needed and told him how to manage the operation and maintenance. The company gave him a one-year equipment guarantee. He is now following the instructions of this company regarding maintenance and the replacement of filters and spare parts. This is a mutually beneficial arrangement, as it guarantees the quality of the product for the operation, while allowing the supplier to make money from maintenance and sale of spare parts.

There has been no coordination between the owner of the project and the government. This entire operation is not regulated in any way by the government. The operation is not licensed by any regulatory authority, but the village inhabitants view the project as a useful service. Because the project owner comes from a well-known family that has a good reputation in the village, he has been able to operate safely and without interference from the authorities. The project owner sells the water jerry cans at cost to the poor when they buy it from the station, which he says, is a moral duty.

There is no societal participation in this project. The owner of the project makes all the decisions and assesses the performance and the quality of work. He determines the prices of the final product in light of the market needs.

Resources and Funding

To start the project, the owner had to raise the capital, find an appropriate place to operate, then buy the right equipment and install it. He also needed to buy tricycles for the delivery side of the operation. To raise the capital, the owner used his own savings plus easy credit from family and friends. He rented a 30 square meter shop on the ground floor of a building. Then he bought the tricycles on an installment plan.

He received technical support from the equipment supplier, which is one of several companies working in the field. The company is used to training those who want to create such projects, which are now fairly common in the countryside and peri-urban areas.

The owner employs four workers, two for operating the equipment and two for delivery, all of whom work under his direct supervision. Delivery doesn’t require any special skills, whereas operation requires a level of training that he was able to provide to the workers himself.

The project required an initial capital of about 80,000 EGP to buy the purification equipment and filters, set up the shop, and pay for overhead and other recurrent costs. Another 7,000 EGP provided a down payment on the two tricycles. At the current volume of business, the monthly operating cost is about 8,000 EGP, which includes rent, salaries, electricity, and maintenance. The top capacity of the purification station is 640 jerry cans a day or 7,680 liters. The jerry cans of purified water are currently sold for 0.5 EGP if collected at the station and for 1 EGP if delivered. The owner of the station makes most of his money from home delivery, and he says that some families consume nearly 4 jerry cans per day.

The project utilizes electricity, charged at the commercial rates, which is the highest bracket for electricity. The water that is being purified is free, as it is obtained through an improvised connection to the water network. Since the project is operating without a license, the owner doesn’t pay any operational or other fees to the government. The project is therefore profitable, but its profitability hinges on its continued use of government water for free. The owner says that if he starts paying for the government water he will have to raise prices. However, competition from rival operations would force him to keep his price down and he may not be able to stay in business. This statement is one that we will revisit at a later point.

Survival and hindrances

The commercial aspect of the operation depends on three things: capital, technical and administrative expertise, and marketing. The owner didn’t have much trouble raising the capital, which he obtained as soft loans from his family and friends. The technical expertise was provided by the company that supplied the equipment and is still supplying the maintenance services. As for the marketing, the demand was already there. The fact that the owner is someone known personally to the consumers not only helped his business, but protected him against government interference so far. The owner is currently trying to branch out into selling bottled drinking water, although he would need a license to do that. The production of bottled water is a more specialized business that is confined to major companies.

The owner’s current status is vulnerable from the legal point of views. His business is run without a license and he obtains water illegally. These matters, plus the level of competition from rival operations, are causes of concern for the owner.

Outcomes and Impact

The owner says that his project has achieved its main aim, which is to provide the local population with clean water at an affordable cost. But he still hopes to operate legally, with government support and a legal license. Many of the village inhabitants now rely for their supply of clean water on the services of this project and on similar services provided by competitors.

Aside from the testing done by the owner, there is no independent or official confirmation of the quality of water. In brief, the state is absent not only from the production aspect, but also from the regulation side of the business.

Sustainability

The project is viable in the strict economic sense of revenues exceeding the operating costs and overhead. But its profitability is contingent on a free supply of water and on the degree of competition posed by rival operators. If the market gets saturated, the current margins of profit may dwindle, thus squeezing at least some operators from the field. In addition, such operations can only remain profitable as long as the government remains incapable of providing the public with clean drinking water.

From the social point of view, the station’s owner says that he is trying to sell water at near cost for those purchasing his product at the shop. His services, he claims, saves lower income households from having to drink polluted water without putting much strain on their finances. The owner, it must be said, has benefited from his network of relations in the village, which is his main protection from government harassment. The community is benefitting from his services and is willing to protect his business.

But how sustainable is this project?

The internal organization of the project is simple, and it all revolves around the owner. There is no institutional structure to the project that may guarantee its continuation in case the owner loses interest or is unable to run the project for any reason. Also of consequence is the fact that project lacks the formal recognition of the state. It has no license to operate, doesn’t pay for the water it is using, and has no health supervision whatsoever. Still other people are starting similar projects in other areas, and they do so in response to a clear and immediate need.

Tadamun’s Vision

This initiative must be seen as a controversial one. Regular access to clean water is a basic right that the state must provide to its citizens. Still, there are many Egyptians, especially in the countryside and peri-urban areas who are denied this right. In view of the government’s inaction, or inability to address the issue, what else can the citizens do?

The citizens are faced with a dilemma: either they accept the status quo and drink water of questionable quality from Hand pumps or the tap (if such options are available) or drink filtered water which they produce at home or buy from various providers. Due to this lamentable reality, hundreds of private-run water treatment facilities have sprouted up in Egyptian villages and the outer rim of cities. In August 2012, the total number of these stations was believed to be around 2,000 across the country. Not all the stations are for-profit. Some have been set up by NGO’s as a charity service to the public.

The state’s role in the phenomenon is confined to its attempts to chase down the owners of these stations and try to close them down. The state is even asking citizens (who rely for their only access to clean water on such facilities) to report them so that they get closed down. Meanwhile, the government has failed to come up with any alternative solutions, not even in the short term.

Now, let’s consider the international agreements which established the right to water as a universal right. The 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights addresses the right to water from two different angles. The first is the right of citizens for a suitable living standard (Article 11). The second is the right of citizens for the highest possible level of health (Article 12). In 2002, the UN Commission on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights issued a document called “general comment no. 15 on Article 12 of the International Covenant.” Comment 15 states that “the human right to water entitles everyone to sufficient, safe, acceptable, physically accessible, and affordable water for personal and domestic use.”

The most pertinent thing about this comment is that it addresses other aspects of water aside from accessibility. These aspects should help us analyze the above initiative and shed light on the problem of drinking water in Egypt in general. These aspects are:

Water sufficiency

Water must be sufficient for the various needs of the population. Water poverty is currently defined at 1,000 cubic meters of fresh water per capita per year. Countries falling behind this level are considered water poor.

Egypt, with an annual per capita water supply of 700 cubic meters and likely to drop to 600 cubic meters by 2025, is considered water poor. In addition, Egypt suffers from a lopsided distribution of water between various governorates. The per capita share of drinking water in Egypt is 259 liter/day nationwide. But it is far higher in Cairo (752) and Alexandria (580) than in al-Menya (105) and Aswan (108). Such disparity is not confined to governorates but exists between one district and another in the same city. Surprisingly, Egypt’s per capita share of pure water is higher than that of Germany, but in Egypt, the problem is the uneven distribution, and the networks of pipes are so dilapidated that up to 50% of the fresh water is wasted or becomes polluted before it reaches the end user.

Water accessibility

People should have access to water without having to go through extraordinary efforts to obtain it. For this to happen, every household should have at least one tap of drinking water. According to a 2008 study conducted by the National Research Centre, nearly 40% of Cairo households receive water for less than 3 hours per day. A survey conducted in the Fayyūm Governorate eight years ago shows that nearly 46% of all households suffer from low water pressure, 30% suffer from irregular supply, and 22% get no water during daytime. The prevalent use of water pumps in various cities and villages offers further evidence of the scale of this problem.

Water quality

Water should be clean and suitable for drinking, cooking, and washing. It should be tasteless, colorless, and free from pollutants and other substances that pose a threat to health.

The scope of the current problem in Egypt is underlined by frequent newspaper reports of cases of poisoning by drinking water, especially in the countryside. In 2011, a newspaper report claimed that “80% of the inhabitants of Assyūt Governorate (that includes four million Egyptians) drink polluted well water.” Even government reports mention the poor quality of the drinking water produced by the government’s water treatment facilities run by the HCDWSD. A government report published in 2009/2010 notes that nearly one half of the water samples produced by government-run facilities in eight different governorates failed to meet the official health standards.

Affordability

Water should not be a commodity. It is a basic human right for every individual. Governments must provide it to all citizens without discrimination and regardless of their financial status. In Egypt, the government sells a cubic meter of purified water to households at a price ranging from 23 to 50 piasters (one Egyptian Pound = 100 piasters) depending on the volume of consumption. Meanwhile, a cubic meter of water actually costs 125 piasters to be produced. Subsidizing water is a common action by the governments worldwide, especially in developing countries. However, some countries use the rising block tariff in order to discourage the overuse of water. Providing an initial amount of water at a low tariff with an incremental rise aims to create a sustainable financial and environmental model for water provision while at the same time providing the basic needs for all citizens. In Egypt, despite the fact that a majority of citizens are deprived the access to clean domestic water, practices of overusing water resources is clearly notable (like for example washing cars and irrigating lawns in the upper class neighborhoods using clean water).

In the case of the private water treatment station discussed above, the owner sells a cubic meter of water from the facility at about 40 EGP, while charging an additional 40 EGP for delivery. In other words, the privately-owned station is selling purified water for at least 80 times the price set by the government-owned HCDWSD. This fact seems to refute the argument, offered by the station owner, that he would have to increase his prices if he were to pay for the water he is using. Now consider the price of a 1.5-liter bottle of water, which is sold by the private companies at around 3 EGP each. This price is about 4,000 times what the government charges for its supply of water.

The case of Sansaft Village in Menūfiyya is worth noting here. In 2012, 4,000 citizens suffered poisoning in Sansaft after drinking polluted water. The government reacted to their ordeal by closing down the private water treatment station supplying this village (an operation that is similar to the one described earlier in detail), blaming it for the problem. In fact, the owner of the Sansaft station had closed the station for a few days at the time of the incident because he had to travel away for the Eid al-Fitr vacation. When he closed the station, the villagers drank the unfiltered government water and were poisoned as a result.

Who is to blame?

When there is a huge inequality between citizens living in different governorates inside the same country in terms of access to clean water, who is to blame?

When the only solution for millions of people is to dig their own wells or do the filtering themselves, who is to blame?

When the difference in cost between government-provided water and privately-purified water is immense, who is to blame?

When this situation continues and becomes a source of profit for many, who is to blame?

Should we blame the private stations and factories that are making incredible gains from selling a “public good” to the public? Should we blame the state for abandoning its role in this respect, and leaving citizens to their own devices?

Is it true that privatization is the answer?

Already, the government is privatizing segments of the sewage service.

In fact, the state doesn’t seem to have a problem with major beverage companies which sell bottled water in the Egyptian market. Yet, it is hell bent on stopping the micro-treatment companies from doing the same. The state wishes to shut down the small, private treatment stations, but it has yet to offer an acceptable alternative to millions of Egyptians who cannot afford bottled water.

Privatization is not the answer. Millions of citizens across the world, from Brazil to Germany and India are fighting for their governments to reclaiming public water. They want companies that had been privatized to be nationalized and they are experimenting with alternative ways for managing water production.

Where does Egypt stand?

Much of Egypt’s drinking water problems stem from mismanagement and the overlapping of authority. The entire water sector needs restructuring, but this is a time-consuming task. In the short term, the government can address the problem through regulating the privately-run water purification stations. Thus, it could supervise the quality of the product and ensure that it is priced in a fair manner. The government can also offer assistance to this sector so as to help it improve its performance.

Then again, is it true that the government supports privatization? What the government truly supports are the major companies that sell bottled water. The government has shown no desire to recognize or help the micro businesses that produce filtered water for the local market.

It would be helpful for the government to learn from the private water treatment facilities, from the decentralization of their services, and their ability to reach clientele in every part of the country. But relying on the private sector may not be the right answer for the medium- and long-term. At one point, the government must think of ways to supply clean water in adequate quantities to all citizens.

Egypt signed the International Covenant of Economic, Social, and Cultural rights in 1967. It is therefore under obligation to uphold all the rights this covenant entails, including the right to water. It is unlikely, however, that the government would move in this direction unless the citizens organize and pressure it to do so.

Lest we forget: water is not a commodity; it is a right.

Related Links

World Bank Indicators

Actualizing the Right to Water: An Egyptian Perspective for an Action Plan

CAPMAS warns of water shortages by 2017

Egypt National Rural Sanitation Strategy

Water Quality Protection in Rural Areas of Egypt

UNDP: Water and Sanitation: The Silent Emergency

Human Development Report 2013

Pipes but no water: A need grows in Egypt

1. “The revolution of Thirst”: Article in Newspaper↩

2. “4000 poisoned in Sansaft village”: Article in Newspaper↩

3. The village of Sarw declared it would secede from the governorate: Article in Newspaper↩

4. Article in Newspaper: Inhabitants of Saft al-Laban occupy the governorate’s building↩

5. The name of the village will remain anonymous since it is representative of a larger trend and operates in a grey legal space.↩

Featured Image by Nasser Nouri on flickr (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Comments