Zinhum Housing Development… The Dream of Slum Dwellers

The place here is very quiet. The houses are widely spaced. Some of the boys are playing with a ball, while others are jumping on the trampoline. Some women sit under a wooden umbrella chatting, while close by a man passes with a broom and a wheelbarrow. Here, you will see no cars, but you can see the Mosque of Muhammad Ali clearly, which is closer to here than it is to Al-Azhar Park. Welcome, you are in Zinhum.

In order to persuade rich people to buy homes in exclusive enclosed residential developments, advertisers resort to phrases such as “Live in the heart of the city, but away from its problems,” “Living above it all,” or focus on the amenities such as schools and kindergartens and the overall cleanliness. They might also market their general spaciousness, large open areas, and the views that you can see from your home. All this could have been said about Telal Zinhum (the hills of Zinhum). Had it been an exclusive residential development, it might have even been called “Zinhum Heights” and the advertising slogan could have been: “Live in the heart of Cairo … for real.” But this is not an exclusive development; there are no fences and no rich people. This is not New Cairo, but an area in the al-Sayyidah Zaynab neighborhood, a low-income blue collar area with governmental schools and ordinary cafes rather than chic coffee shops. There are no golf courses or shopping malls on the outskirts of the district, but instead amateur pigeon breeders and grocers on the border with al-Sayyidah Zaynab.

Telal Zinhum represents a unique case of in situ development, or development without displacement. Residents of other districts often point to Zinhum as their ideal model for developing and improving their homes and communities since it strengthens their economic assets and social ties, as their most pressing problems are addressed and largely resolved. The government typically has characterized informal areas as undesirable, and dealt with them harshly. Typically, they “develop” informal areas by demolishing them and displacing residents to homes on the outskirts of the city, quite far from their original residential area. If you live in an informal area in the center of Cairo and the government wants to “develop” your neighborhood, you might be given a new home in al-Salām City, el-Nahda, or the Sixth of October City, and you will have no other choice. This will result in new hardships. There are fewer job opportunities in the exurbs of Cairo and the breadwinner of the family risks losing their job that is close to their previous home. The family will suffer from losing the network of social relationships and the children will be obliged to leave their schools. Maintaining jobs and social networks in the center of city would require spending a higher proportion of family income on transportation to travel to and from the center of the city as well as a great deal of time.

The development of Telal Zinhum is special for two reasons. First, as the project was completed, residents were rehoused in the same place. Second, government officials, civil society organizations, residents and businessmen cooperated with one another in the development process and formed fruitful partnerships while sharing responsibility for the project. Such collaboration in neighborhood development is unfortunately, rare.

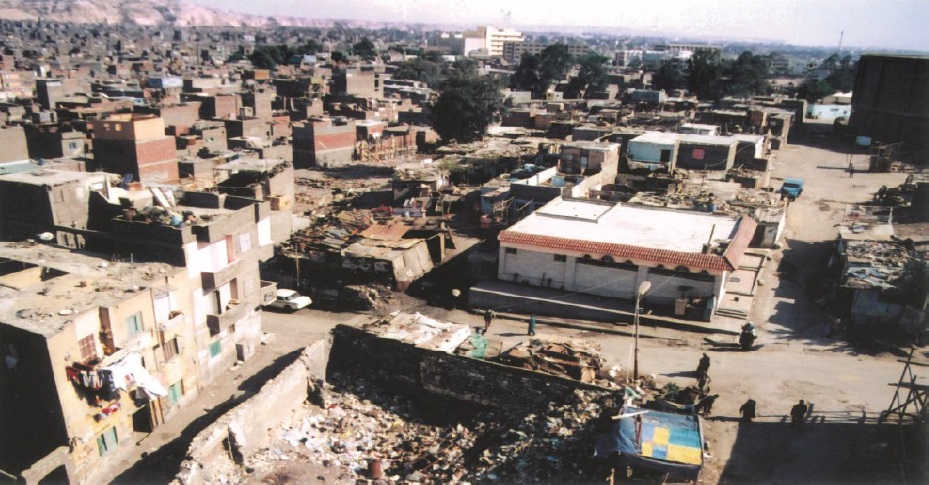

Situation before the Development

Many of those who heard or read about the project of the development of Zinhum knew that the area, before the intervention, was composed of a group of wooden huts in an extremely dilapidated state, structurally, environmentally and socially. But what many do not know is that many of those huts were actually constructed as temporary shelters by the Cairo Governorate more than 40 years ago, for those whose houses had collapsed in adjacent neighborhoods, as temporary refuge, until the governorate was able to build them new houses. ʿEīd, one of the elderly residents of the area, told us that he lived in Zinhum for 30 years in a wooden hut (3*9 meters) that was given to him by the governorate, after the collapse of his house which was in a neighboring area. He was finally given a newly built unit in phase two of Zinhum upgrading project in 2004. During the intervening years, others searching for shelter came to the area, and built more huts for themselves. In 1999, the number of inhabitants in Zinhum area had reached around 20,000 people, or about 4,000 families, in a total area of 50 feddans.1

History of the area

The area also has historical roots; Zinhum is in the same location that was occupied by al-‘Askar City, built by the first Abbasid governor in Egypt (A.D. 750) as a new ruling headquarters. The city was located north to its predecessor al-Fustāt (built in A.D. 641). In A.D. 869 Ahmed `Ibn Tūlūn came to power, and he built another town to the north of the Military City called Al Qatae’, where he built his famous mosque. Nothing remains from those three towns except the mosque of ’Amr `Ibn el-ʿāss in al-Fustāt and the mosque of `Ibn Tūlūn close to the northern edge of Zinhum. In spite of its historical location, Zinhum has no archaeological sites, perhaps because of the short life span of the al-‘Askar City. Those three cities merged later to become Cairo, the great city built by the Fatimids in A.D. 969.

In the modern era, Zinhum was mostly hills of rock and sand. Some of the older residents say that the hills were transformed into a nice park during the reign of president Gamal Abdel Nasser. That was when the area was given the name “Zinhum Gardens”.

The Project’s Idea

Political influence was the main driver for this project. It all started in 1988 when Mrs. Suzanne Mubarak, the wife of the former president Hosni Mubarak, decided to develop the area and commissioned the Egyptian Red Crescent Society to do so. Mrs. Mubarak made this decision during one of her visits to the headquarters of the Red Crescent Society, located in Zinhum, while she served as the President of the Red Crescent Society. It is likely that because Suzanne Mubarak’s name was linked to the project it drew the project in a direction that was atypical for redevelopment projects. There was considerable interest from many people to participate in the project in order to curry favor with Mrs. Mubarak to facilitate their own private businesses or careers later on. Governmental entities such as Cairo governorate jumped at the opportunity to assist, businessmen were eager to make donations to the project, and contractors volunteered to build the houses for free.

Project Phases and Steps of Implementation

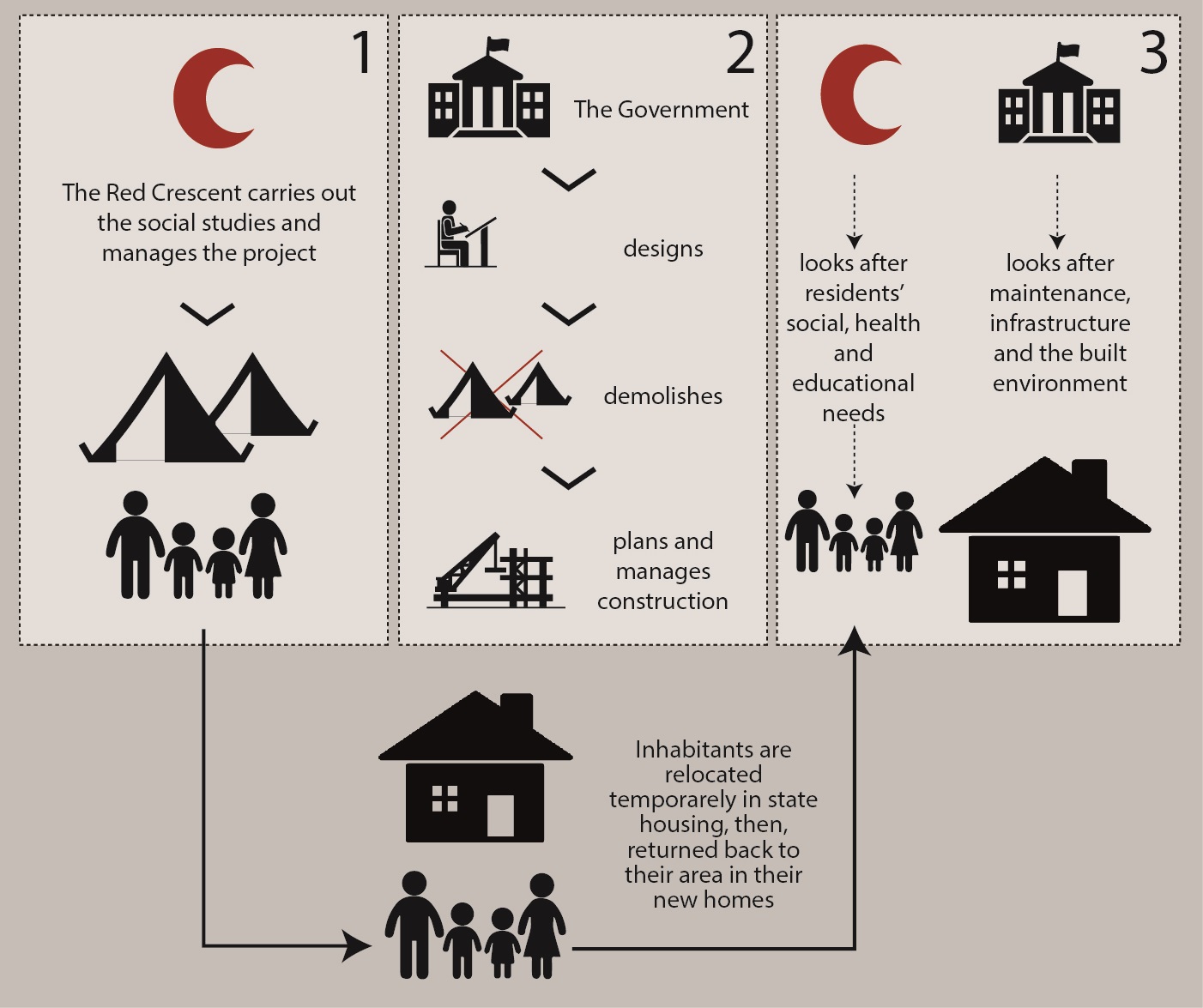

Initially, the Red Crescent Society conducted an assessment for the area, and created a complete survey for the social and economic profile of the residents. They divided the area into three segments, which would be redeveloped in succession. In each phase, the residents were transferred to temporary homes in el-Nahda and Mothallath Helwan until the old houses were demolished, the infrastructure was installed and the construction of the new buildings were completed. After that, they were returned back to their area in new houses.

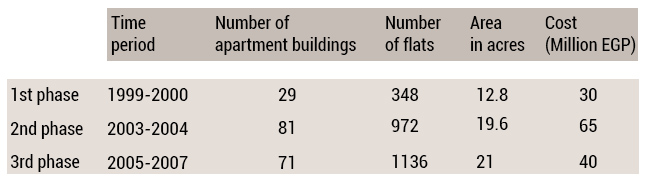

The first phase started in 1999 and was finished in 2000, while the second and third phases lasted between 2003 to 2004 and 2005 to 2007 respectively. The area of each flat is 67 square meters, consisting of two rooms, one living room, a kitchen and a bathroom. The footprint area did not exceed 30% of the total area.

Sources for the information in the table above: The website of the Egyptian Red Crescent، Report of the Center for Social Research the American University July 2011.

Based on a report by the Red Crescent Society, the project was organized along two main axes:

The first axis: Social development of the residents through education, healthcare and cultural programs provided by the RCS.

The second axis: Complete demolition of the huts, planning and reconstruction of the area with new modern houses, open spaces, green areas, services and facilities.

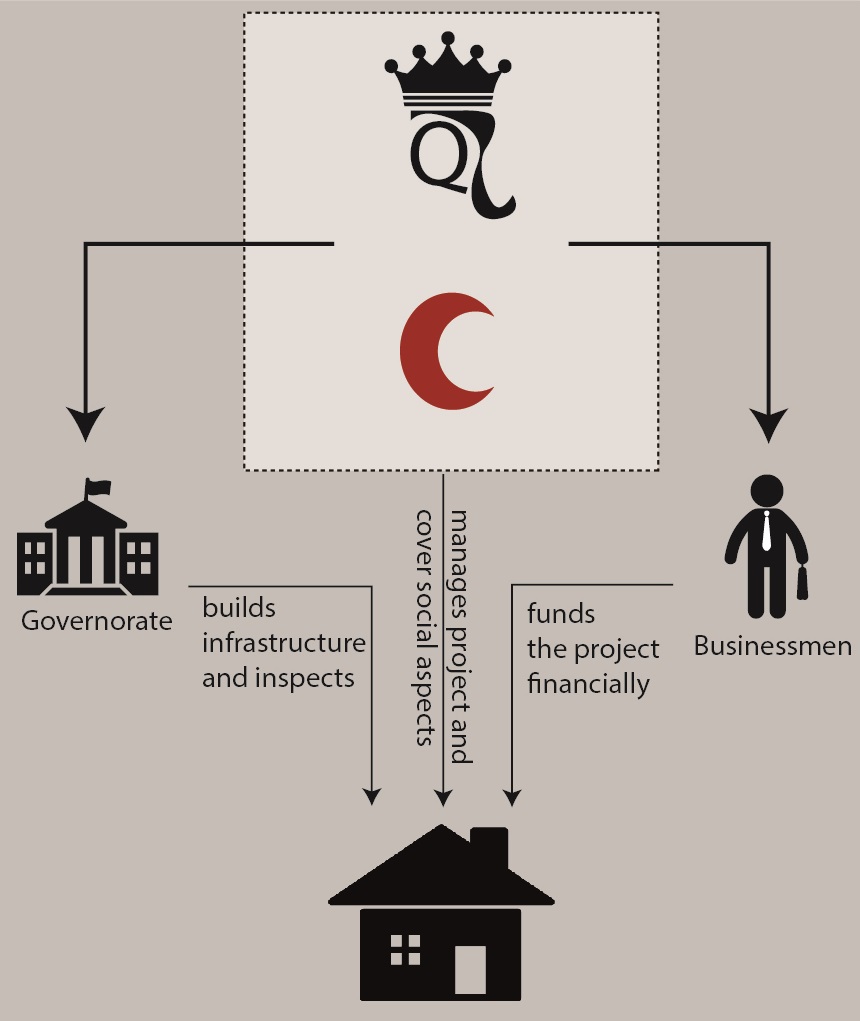

Resources and Funding

The project depended on a multiple funding mechanism, which included government entities, NGOs, and businessmen. The total cost of the project was 200 million Egyptian pounds. The government entities represented by the Cairo governorate funded the clearance operations, site preparation and the cost of supplying basic facilities for the three phases of the project (a total cost of 50 million pounds). The Egyptian Red Crescent Society collected and managed the civil and private funding (grants from businessmen, contractors, and NGOs) to construct residential buildings (142 million pounds) and service buildings (8 million pounds). The project also included the upgrading and replacement of the infrastructure network, namely water, sewage and electricity.

The project did not suffer from any financial impediments. The land was owned by the governorate, so it was given to the project for free. Construction costs were covered by donations from businessmen as mentioned above. The project does not generate any profit, as it was launched by the Red Crescent Society, which is a non-profit organization. Rents are supposed to cover the cost of maintenance and garbage collection.

Because several parties participated in the project, it was important to define roles and priorities. The RSC was responsible for managing the project and the resources, as well as fund raising and performing the necessary studies. The Cairo Governorate took the lead on urban and architectural planning, and hired a consultant (Associated Consultants) for this dimension of the project. The governorate also provided temporary housing and supervised the construction of the project. The construction companies built the houses according to the governorate’s plan. During and after the implementation of the project the Red Crescent Society provided social services, technical education, adult literacy programs, computer workshops, educational trips for children, and conducted health awareness campaigns. It built a cultural center, a center for maternal and child care and two day care centers for children and also provided furniture to the poorer families. In order to communicate with residents, it appointed coordinators from among the inhabitants of the area to learn about the needs of the people and help solve their problems and to inform the residents about the project’s schedule and its various activities.

Results and Impact

The Red Crescent Society shares the residents’ enthusiasm for the project and their sense of its success. Although the residents have some reservations concerning the quality of some services like health facilities, as well as the issue of public space maintenance, they acknowledge the difference between their current homes and the previous ones, for at least now they have a roof to protect them, they have natural gas, potable water, a sewage system, electricity, and garbage collection services. The streets are clean and there is a lot of space for picnics and for the children to play. The whole district has been built soundly, there are more services from many NGOs for the residents and there has been a slight improvement in the percentages of poverty and unemployment.

There are other new amenities available in the district, such as a hospital, a nursery and a community center, which are all affiliated with the Red Crescent with the exception of the Talʿat Harb Cultural Center, which is affiliated with the Ministry of Culture. There is also a police station and an adequate number of schools. Transportation is not a problem for the residents because the area is close to the center of Cairo. The services provided by the RCS compensated for the absence of government services in some sectors. However, the residents complain about the service in the hospital claiming that the physicians are never present and it does not function efficiently. There is a private company responsible for garbage collection which was hired through the RCS during and after the completion of the project. The company collects solid garbage from the houses and also cleans the streets. Residents commend the performance of the company and indicate their satisfaction with the level of street cleanliness. It is obvious that the level of cleanliness in the area is very good, compared to the surrounding areas.

From the point of view of the RCS and the residents, what the project needs now is governmental attention, although they have different ideas about what that means. While both request better maintenance of the houses and public areas, the RCS wants the governorate to remove all encroachments (such as adding balconies or extensions to the flats) and shut down unlicensed informal economic or commercial activities. Yet, many residents articulate their need for shops, workshops and other economic activities, for, as they clarified that they do not wish to live in chaos, but they want the authorities to realistically address their pragmatic economic and employment needs.

Sustainability

Projects done at the behest of the former president’s wife were never hindered by bureaucratic procedures, the lack of resources, or any other barriers that usually impede government or private development projects. On the contrary, once the former president’s wife was linked with the project, many governmental entities, businessmen, and contractors vied to donate money and their expertise in order to gain her approval. Yet, this kind of patronage did not ensure the project’s sustainability. In an institutional state, urban development is subject to a governmental plan prepared by experts and specialists to identify priority areas, the most appropriate intervention, and how to achieve economic, environmental and institutional sustainability after the completion of the project. A project’s viability and sustainability is not supposed to depend on a single person, since once this person disappears, all interest in the project may end. Any possibilities to replicate the project elsewhere may also decline under a patronage model.

In Zinhum, the level of maintenance and services with which the project began in its early stages started to decrease, especially after the 2011 revolution and the loss of presidential support for the project. In addition, maintenance tasks were transferred to the local district council, which dealt with that area like any other one. This consequently led to the deterioration of the condition of public spaces such as green areas and street lighting. For example, as street lamps burned out and needed to be changed, and nobody maintains them. As a result, the streets are dark at night and residents have resorted to extending wires from their homes and attaching lamps outside the buildings for illumination. The gardens whose pictures had been seen in the earlier pre-2011 news and reports on the project are now barren. Our source at the RCS said that it is the responsibility of the residents to maintain the gardens. Before the revolution, they used to sit around the lawn, but now they sit on the lawn, which degraded it. While the residents said that the lawns were planted once at the beginning of the project and the local council sent workers for irrigation and maintenance, but it was neglected soon thereafter.

With respect to economical sustainability, most of the expenses of the project depended on the donations of businessmen, contractors and NGOs, which is commendable, but as mentioned above, their eagerness to donate was not entirely altruistic or due to their concern for the poor. Behind their generosity was the desire for privilege and future gains. As to long term economical sustainability, the monthly rent paid by the residents is used for regular maintenance work such as garbage collection and street cleaning, but other work, such as maintaining lamp posts, mowing the lawns, and tending the garden benches is not supported by the monthly rent. These tasks are supposed to be the responsibility of the city district within its allocated budget, but they are not being carried out.

When talking about sustainability, it is necessary to mention the design and planning aspects. There are several phases in any urban or architectural project. The first phase is the design, followed by the implementation phase, and is related to the criteria underlying the architecture and urban design for a project. The design has followed standard design guidelines that are implemented in any new compound or gated community built on the outskirts of Cairo: wide streets, with an abundance of parking spaces and green areas. The footprint area did not exceed 30%.

The next phase that comes after the project implementation is the post-occupancy evaluation. No urban or architectural project ends with the completion of the implementation stage, but the process of evaluation and follow-up should continue after occupancy to observe any flaws in the design and monitor usage patterns in the public spaces.

There are several questions that arise in the case of the Zinhum project: are the textbook standards for architectural design suitable for implementation in any place and for any user? Have the residents been consulted regarding the areas they need for their flats and their various uses for the public spaces? Have the different and various needs been taken into account in the design, or it has been a one model approach that fits for all? A thorough register of the number of residents and their social and economic status had been compiled before starting the project, but has there been a study of the usage patterns of public and private spaces, the different needs of the residents and their daily habits?

When some of the residents were asked – randomly during the site investigation – about the degree of their satisfaction with the size of their apartments, many of them explained that it is small and does not accommodate their family size. This remark matches with the result of a study done after five years of the completion of phase one of the project, by a researcher in University of Bahrain. The researcher used a questionnaire to measure the degree of satisfaction of the residents about various design and planning issues of the project. The survey showed that although 58% of the residents were generally satisfied with the unit sizes, the space allocation for some of the activities were not satisfactory such as the sleeping area. The research showed that 55% of the families are not satisfied with the surface area allocated to bedrooms; this is due to the varying sizes of the families which range from 4 to 8 members. The flats are designed to accommodate a 4 member family; however, this is not the case for all Zinhum residents. Some families use part of the living room as a third bedroom for the children. As for the service areas, 72% expressed their dissatisfaction, according to the same study, due to the small areas of the bathroom and kitchen and the absence of a space for hanging the laundry. The issue of the laundry was solved later in the second and third phases by adding balconies.

There are some remarks also concerning the urban planning of the area. Referring to one of the wide inner streets in the district, which has large parking lots containing only one or two cars at the most – since most Zinhum residents do not own private cars – one woman commented that the space occupied by those streets could have been used to increase the areas of the flats, even by a small percentage. She also added that she and her daughters fear going out during the night because the streets are dark and devoid of any activity. This is in sharp contrast to the low-income, blue collar areas in central Cairo, where the streets are always bustling with pedestrians and people sitting at cafes or shopping, day and night. Very wide streets may sometimes lead to a sense of insecurity, in contrast to the relatively narrow streets which characterize the low-income areas. The narrow, intimate streets allow all the residents to see everything that is happening on the street, whereas the wide streets of Zinhum do not afford easy surveillance and illicit activities are easier to hide from plain view.

This woman also wondered why the walls surrounding the area aren’t used for activities like shops that would generate an income for the residents and make the area livelier and safer. Apart from evaluating this idea in particular, this shows that the residents might have a different point of view regarding the nature of the community in which they want to live; this may be different than the standard specifications of the enclosed residential developments found on the outskirts of Cairo. Some of the residents have made partial modifications to their flats such as adding a balcony or building a kiosk. This once more shows the absence of genuine community participation in the design process from the beginning, or the lack of understanding of the real needs of the residents, despite the registration process and initial studies carried out by the project team.

As for the public spaces, we noticed more than once that residents had fenced a particular green area and were taking good care of it, contrary to the other green areas that no one is caring for them. The fence which the residents are constructing does not impede entering the area; it only outlines its imaginary boundaries. This observation raises a very important point that is often observed in housing projects, who owns the public spaces or the common areas, and who is responsible for taking care of them?

The RCS thinks poorly of the modifications done by the residents to their units such as building poultry coops and huts on top of buildings, converting their ground floor windows to shops selling food, detergents or stationary. They argue that the residents are inclined to live in a disorganized way, spoiling the ideal image of the project. The RCS also complains about the lack of cooperation from the city district council. The administration at the RCS fears that the delay in removing the encroachments will create a snowball effect of problems, making it impossible to solve later on.

The residents view the situation from another perspective. The ground floor windows are very low, which allow people to see into the units when passing by. They build walls for privacy and to prevent people from urinating under their windows. With respect to the kiosks they say that the area lacks commercial services and they are filling this need. There has been an initial plan to build a commercial market in the area, but it never materialized. Without these kiosks and shops, the residents would have to go to al-Sayyidah Zaynab district to buy their goods. People said that the local district council does not harass them, and only prohibits them to build any permanent structures.

Official reports identify the Zinhum project as a model of community participation, but reality says something different. Although the representation of the residents was greater than in similar housing projects, it still was at the level of informing, or at most at the level of consultation. The project was not devised to meet the needs of residents, but to meet the needs of residents as the RCS and the governorate perceived them.

Replication and Future Plans

It is difficult to predict the possibility of replicating the Zinhum development project because of the special circumstances surrounding the project and its level of political support. Given the current political changes, we do not know if it is possible to replicate the success of the experiment without the support and pressure from an institution such as the Presidency.

Tadamun’s Vision

Officials in Egypt often talk about the problems of informal areas and/or State plans to develop them, or according to their expression “eradicate them.” But what are the policies of the State to improve those areas? What are the various interventions or policies that the State must pursue to develop these areas, while recognizing their urban problems? What are the criteria according to which the decisions are made to follow a particular policy in developing this area or that?

According to the guide for decision makers for the participatory development of informal areas issued by the German Society for International Cooperation (GIZ) in 2010, there are five general approaches to improving informal areas:

- The supply of public utilities: this pattern targets areas whose built environment is in a good condition.

- Sectorial development: focusing on the supply of services within one particular sector, such as roads, education or health facilities, or any other sectors.

- Planning and partial restructuring of the area: This is done by developing a plan that proposes to widen the main streets and create some empty territory for services.

- Complete redevelopment of the site (in situ): by the gradual demolition and construction of alternate housing in the same location.

- Complete redevelopment with relocation of residents to other remote areas.

In contrast to the displacement and resettlement of residents to the outskirts of the city, Zinhum represents one of the few good models for in-situ development, where residents are rehoused on the original site. People believe that this model is successful because it maintains the network of social relations among the residents of the region, and resettles residents in the same area again, next to their businesses and schools, which rarely occurs in most government plans and projects for deteriorating informal areas.

Although everyone agrees on the success of the project, the disparity between the visions of the various parties is apparent. There was an ideal of what a residential area for low-income people should look like in the minds of those in charge of the project. They considered any deviation from this ideal a result of the disorganized, chaotic habits of residents and believed these deviations must be confronted. However, this ideal model ignores some of the needs of the residents who are not at all concerned with the ideal of the “experts.”

The housing plan for Zinhum seems to be influenced by two sometimes conflicting patterns for housing: the socialist, public housing model, and the residential enclave model. The influence of the socialist planning style can be seen in the similarity of buildings, their orderly stacking, the assumption of the universal needs and circumstances of the residents (one size fits all), and the assumption of greater knowledge regarding what is suitable for the residents. For example, all apartments are the same size (67 square meters) regardless of the number of family members. This contradicts the variation already found in Cairo’s neighborhoods, which is a natural response to the social needs inside the same community.

At the same time, the vision of the RCS was influenced by the exclusive residential enclaves similar to Northern Coasts resorts. This ideal image for what the area’s urban image should look like, which was mainly produced through a top down decision from the first lady or the RCS, is absolutely contrary to Cairo’s complex urban fabric and its layers of history and high urban densities. The low-density urban fabric of Zinhum may have positive impacts on the quality of life but it is simply infeasible to replicate the model in other neighborhoods of Cairo.

The most important challenge facing Zinhum now is the ability to manage the same quality of public services that was proposed at the beginning of the project. This challenge now must be met by the administrative capabilities of the local council of al-Sayyidah Zaynab district. This opportunity can be used to work on raising the efficiency of the local administration which will be beneficial not only to the Zinhum area but also on the rest of the areas in the neighborhood.

Still remains the question about the real driver behind the decision to develop the area of Zinhum in this special way, apart from eviction and permanent relocation of residents. It was done on a top-down approach without a pressure from the people.

In conclusion, the project presents a positive experience to how the government can deal with the informal areas without relocation of its residents, even if political patronage aided its success. However, the project did not move ordinary urban development policy closer to integrating, distributing, and mobilizing or enhancing capable and representative local government.

further readings

Archnet Digital Library: Zeinhom Slum Area Rehabilitation

Fire in Zinhum area

Egyptian Red Crescent: Summary of the Annual Reports During the period 2003 – 2009

Gardens instead

1. the Egyptian Red Crescent

2. Zeinab Khadr and Lamia Bulbul, 2011, Egyptian Red Crescent in Zeinhum: Impact Assessment of Comprehensive Community Development Model for Slums Upgrading

Featured Photo by Rehab Sobhi, used with permission.

Comments