‘Izbit Awlād ‘Allām

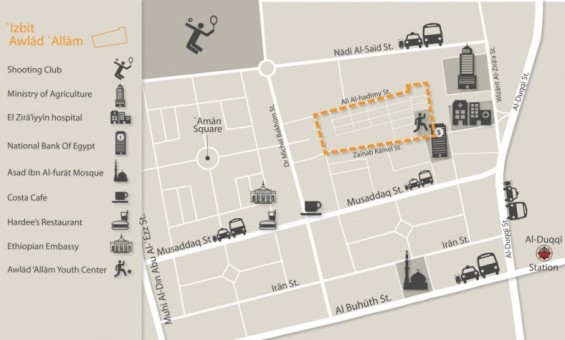

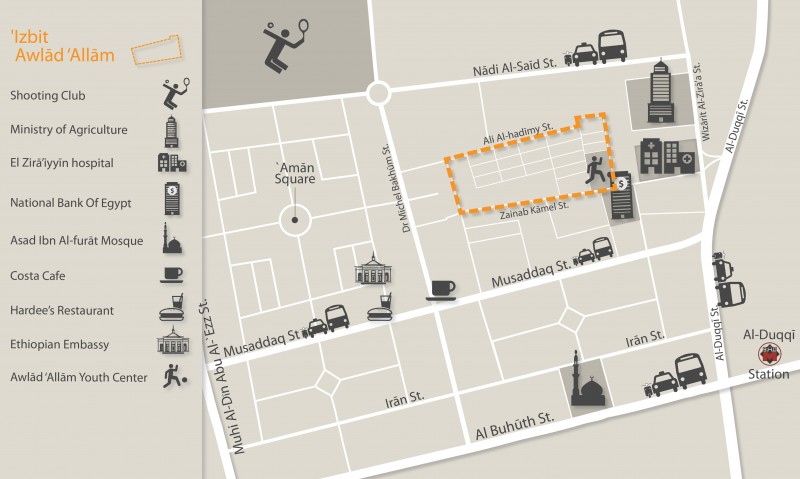

Al-Duqqī is an upscale district in al-Gīza governorate with many foreign embassies, investment banks, chic coffee shops, and government offices. It is a well-planned area with wide, straight roads and proper traffic circles. At the heart of al-Duqqī, a short walk from the Shooting Club – an upscale sports club frequented by upper-middle-class Egyptians – lies a neighborhood obscured by high-rise buildings and cut off from the main roads called ‘Izbit Awlād ‘Allām (hereafter referred to as Awlād ‘Allām or the ‘Izba).1 Despite the popularity of the surrounding area and its central location in the district, many al-Duqqī residents do not even know Awlād ‘Allām exists. Many of those who have heard of the area simply know it as one of al-Duqqī’s four informal areas or “mantiqa ‘ashwaeya,” a label that many of the ‘Izba residents dislike.

‘IzbitAwlād Allām (‘Izbit Fatima Hanim) – 1920 General Map of Cairo, United States Library of Congress

Contrary to being a “haphazard” area as the Arabic term for informal area (mantiqa ‘ashwaeya) implies, Awlād ‘Allām dates back over 100 years and is included in official maps from the early 1900s (see the map from 1920). It is said that during this time the area was much larger, but as land parcels were repeatedly sold, the area progressively shrank to become what it is today: a small square of informality – or perhaps semi-informality might be a more accurate term – in the heart of one of Greater Cairo’s more affluent neighborhoods.2

Awlād Allām in Numbers

Governorate: al-Gīza

District: al-Duqqī

Area: Approximately 6.6 acres (0.03 km2) according to the ISDF (The Informal Settlements Development Facility, 2013).3

Population: Approximately 10,000 according to a 2008 study of informal areas by Egypt’s Information Decision Support Center (2008), while residents and various news articles estimate it to be between 35,000 and 40,000 residents.4

The Story of ‘Izbit Awlād Allām

The ‘Izba was originally agricultural land that belonged to the paternal aunt of King Farouk, Princess Fatima Ismail (1853-1920). Princess Fatima owned large parcels of land in al-Gīza governorate and habitually donated pieces of property as endowments for various causes, including the land on which Cairo University was built. Awlād Allām and several of its surrounding areas were part of an endowment Princess Fatima gave to host the peasants that farmed her land. The process of endowing the land to her peasants took place through the official channels of the Ministry of Awqāf (Religious Endowments) and such lands thereafter became part of the lands administered by the Egyptian Awqāf Authority (EAA). Over time, the area grew to accommodate the growing population and the newcomers who arrived from outside the area to rent inexpensive apartments. The ‘Izba is named after Sheikh ‘Allām, one of the area’s early residents. On official maps, it is known as ‘Izbit Fatima Hanim. Awlād Allām is surrounded by the Agricultural Museum and the Ministry of Agriculture to the East, the shooting club to the North West, and the popular Musaddaq Street to the south.

Just like many other areas in the al-Gīza governorate, Awlād ‘Allām was originally surrounded by agricultural land that was later transformed into urban residential and commercial areas. Al-Duqqī, the district within which Awlād ‘Allām lies, was officially incorporated into al-Gīza’s urban cordon in 1964. This, along with its proximity to downtown Cairo, made it a highly-demanded residential location. Al-Duqqī began as a place where people built upscale villas, but over the years most villas were destroyed and replaced by high-rise apartment buildings, as was the case in many Greater Cairo neighborhoods.

The area surrounding Awlād ‘Allām has undergone many changes throughout the past few decades and yet the ‘Izba itself has retained much of its original character. Its narrow streets and the close proximity of neighboring homes are characteristic of many areas in Egypt that grew organically. Many of the streets are known by the names of prominent families who once lived there such as Mahmoud Al-Shīmi and Gamāl Fouʾād, even if their official names are different and very few of their descendants still live there.

The area witnessed some physical and demographic changes largely linked to the construction of the 6th of October Bridge, which started in 1969. This massive bridge, which today extends from al-Duqqī to Heliopolis and Nasr City in Eastern Cairo, further highlighted the strategic location of Awlād ‘Allām. As Egyptian internal migration increased, more people flocked to the ‘Izba in search of affordable housing, and by the 1970s residents had built up most of the area, and even managed to provide many basic services.

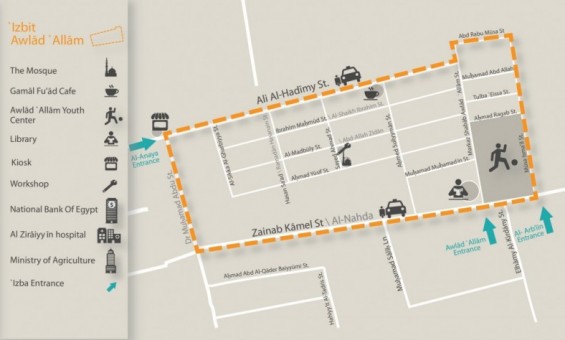

Today, according to residents, the ‘Izba is divided into three parts called al-Arba’een, al-Inaya, and Awlād ‘Allām. The al-Arba’een area constitutes the original part of the ‘Izba where the peasants of Princess Fatima lived, while the other parts were farmed by the residents. By the 1970s the ‘Izba had lost its agricultural character and, as mentioned above, had become almost completely built-up, and encompassed a wider area than what is today considered Awlād ‘Allām. Some of the most popular landmarks pointed out by residents include the library, the youth center, the mosque, the coffee-shop, and the area of workshops.

Residents insist that they do not live in an informal area. The area pre-dates any formal planning activities in al-Duqqi and was included in the governorate’s early official planning schemes. However, the website of the al-Gīza Governorate refers to the area as a manteqa ‘ashwaeya “haphazard/informal area,” and includes it in its five-year informal area development plan. The district manager of al-Duqqī, Azza El-Sherif – who also happens to be the first woman to become a district manager in al-Gīza governorate – has also used the same term to describe the area in her statements to the media.5

Despite the fact that official statements to the media refer to the area as informal, its status is actually much more complicated. Awlād ‘Allām cannot easily be described as an informal area since it is included in official maps from the early 1900s. It also cannot be easily described as illegal since the area’s original residents had the legal right to be on the land.

Awlād ‘Allām lies on a plot of land that falls under the waqf system which is similar to the Western concept of trust laws. 6AUSAID report (2010) on property rights in Egypt describes how the waqf system applies to land as follows:7

Trust land is land set aside by the state for charitable or religious purposes and is usually administered by the Ministry of Awqāf. The purpose for categorizing land as Waqf is to prevent subdivision and to eliminate conflict among descendants. The revenues from the land belong to the beneficiary; Waqf land cannot be sold or mortgaged.

Most of the properties that were donated to the Ministry of Awqāf were plots of land that needed to be farmed or maintained in order to continue to generate income. In light of this, the Ministry of Awqāf made use of a form of tenure called “ḥikr” which allows individuals to pay a rent to the Ministry in exchange for making use of a plot of waqf land.8 Awlād ‘Allām falls under this system, however, ḥikr tenure is no longer legally recognized and residents living on such ḥikr lands are expected to use certain legal provisions that allow them to purchase the land and legalize their situation.9 Law No. (43/1982) states that a ḥikr committee should be established and charged with identifying, pricing, and selling ḥikr land. This committee would also be responsible for solving all disputes related to such lands; however, there are still several ongoing disputes over this type of land, usually related to pricing.

Residents of Awlād ‘Allām have been trying to legalize their situation with the EAA, for the past few decades, but all attempts so far have failed. According to residents, this is due to the ʿIzba’s strategic location which makes it quite valuable and a prime area for investment. They claim that the Minister of Awqāf tried to obtain an eviction notice for the area during the 1950s but lost the case and the appeal, meaning he could not file the case again. However, unwilling to give up such a valuable location, the EAA is insisting on demanding today’s market prices for the land. In the early 2000s a new series of informal negotiations began between some residents and the EAA, revolving around the price since market forces and inflation had greatly raised the value of the land. These negotiations are still taking place today, yet according to residents, negotiations have reached a standstill as the Ministry refuses to lower the price and the residents refuse to pay the high market price.

This ongoing dispute places Awlād ‘Allām’s residents in a legal grey-zone since some of them (the descendants of Princess Fatima’s peasants) claim they have documents to prove their legal right to be on the land, but this legality is invisible in the eyes of the law.10 Other residents (those who arrived later) have no form of legal tenure since they settled on the land through an informal subdivision process that was not recognized by the official housing and finance institutions. However, the area cannot be simply dismissed as ‘informal’ or ‘illegal’ since it exists on official maps and actually constitutes part of al-Duqqī’s historic core.

Unfortunately, such legal ambiguity is not unique to Awlād ‘Allām and continues to affect many areas around Egypt. Yet, nobody seems to be able to figure out a solution to this chronic problem.

The Place and the People

Most buildings in Awlād ‘Allām are residential, but some include ground-level commercial uses such as workshops, coffee shops, and convenience stores. The building bulk, height, and quality vary greatly in Awlād ‘Allām. Building heights vary from one-story homes to multi-story buildings. There are many new buildings, several of which were built within the last three years in the wake of the 2011 revolution and the subsequent absence of the rule of law. There are many old buildings, some of which are built with brick rather than concrete, and others that are severely dilapidated and are susceptible to collapse.

The population of Awlād ‘Allām includes a small percentage of people who are – or are descendants of – owners, meaning that they constructed buildings themselves and have informal documentation proving their ownership. But according to residents, the majority of the area’s inhabitants are actually renters. While no formal studies have been done to confirm this, some estimate that up to 90% of residents are renters, some of whom follow the old rent law (permanent contracts with fixed rents), and some of whom follow the new rent law with one to two year contracts. Most owners are concentrated within the al-Arba’een part of the ‘Izba, which hosts the forty homes where Princess Fatima’s peasants were originally housed. That is the area where the people who constructed the buildings continued to live there. The rest of the ‘Izba is mostly composed of renters as many of those who constructed the original buildings moved to other parts of the city and now rent to tenants.

While in many of Egypt’s informal areas one tends to find clusters of residents from the same village or governorate, Awlād Allām’s residents come from different parts of the country including the Abū Sreea’ family from Aswan governorate, the Shindi family from al-Munūfeyya governorate, and the Abdel Latīf family from al-Saff village in al-Gīza governorate. While there are not a large number of residents that are related by blood, many of the ‘Izba’s residents today are related by marriage, thus increasing the area’s social value for its population due to its strong social capital.

The majority of residents of Awlād ‘Allām are part of the working class, but the ‘Izba is home to people from various parts of the socioeconomic spectrum, including construction workers, lawyers, engineers, and politicians. This is something the residents are particularly proud of, as the ‘Izba has produced some prominent figures such as Ramadan Hassanein who was head of the Appeals Court in Assiut governorate, Hussein Shukry who is a former football player in Egypt’s most prominent team al-Ahly, Hisham Mubarak who was a prominent lawyer and human rights activist, and Ahmed Sharaf al-Din who was also a prominent lawyer.

While there are some jobs in the shops and workshops within the neighborhood, most residents work in the surrounding al-Duqqī district, and thus contribute significantly to the economy of al-Duqqī and al-Gīza governorate as a whole. But the contribution of Awlād ‘Allām’s residents seems to extend to political life as well, as many political parties and groups have been active in the area especially around elections time. For example, in 2010 during the parliamentary elections, the al-Wafd candidate for the al-Duqqī district launched a campaign centered around granting tenure security to Awlād ‘Allām’s residents. In 2011 a few months after the January 25th revolution, the 6th of April political group launched a political awareness campaign in the area related to constitutional and legal rights. And in early 2013 the Freedom and Justice Party (the political arm of the Muslim Brotherhood) coordinated with the municipality to conduct infrastructure maintenance and a general needs assessment for the area. Additionally, residents spoke of political parties distributing bags of basic foodstuffs such as rice and oil. Unfortunately, residents also claim that most political parties diverted their attention elsewhere as soon as elections were over and the area ceased to be a political priority.

What are the Problems of ‘Izbit Awlād ‘Allām?

Most problems in Awlād ‘Allām are linked in one way or another to the area’s pseudo-illegal status and the residents’ lack of tenure. The issue of tenure and legality is not simply about a piece of paper, but rather about every person’s right to have an adequate home. The right to adequate housing encompasses several factors such as security of tenure, physical safety, and access to services. The ‘Izba’s legal ambiguity has been an obstacle to the fulfillment of such rights, and as mentioned above, the majority of residents currently have no form of tenure and thus are potentially vulnerable to eviction if the government so decides.

Regarding physical safety, several buildings in the area suffer from deteriorated structures as a result of a combination of lack of maintenance and badly constructed water and sanitation networks that leak into the buildings’ foundations. Many residents have tried to obtain official permits from the municipality to renovate their homes but were not successful. In fact, because of the pseudo-illegal status of the area, a building moratorium has been in place for many years, making residents vulnerable to fines if they attempt to build or renovate. In the security vacuum that followed the January 25th 2011 revolution many residents decided it was time to take matters into their own hands, and renovated their homes without a permit. Of course, not all building owners did this; some unsafe buildings still remain and building collapses occur from time to time. However, today such buildings constitute a small percentage of the area.

Despite this, the latest (2013) report by the ISDF still includes Awlād ‘Allām in its list of unsafe areas (describing it as “level 2 unsafe” which refers to structural deterioration and buildings prone to collapse). The ISDF’s national plan states that level 2 areas are divided into areas that can be used for extracting funds and those that do not have this potential. Areas that can be used for extracting funds encompass those that include large swathes of vacant land that could potentially be taken advantage of, or areas like Awlād ‘Allām that are on valuable land due to their strategic location.12 Thus, according to the ISDF an area such as Awlād ‘Allām could be used to extract the cost of development or to extract additional resources that could be utilized to improve other areas that do not have the same financial potential. The ISDF plan specifically discusses areas that lie on Awqāf land and suggests “the great majority of these areas can be used for cost reclamation through their low density which allows for increasing construction and making use of vacant lands.” It is unclear whether such a statement is intended to be applied to Awlād ‘Allām or not, but the area can in no way be described as one of low density.

As for infrastructure and services, residents complained about the difficulties they face in accessing butane gas used for cooking in most Egyptian households as the country has experienced nation-wide shortages in recent months. The company distributing the gas canisters would only come to the area once every two weeks and would sell the canisters at a higher price than the official one. The alternative to using butane gas is to install a natural gas connection to the home. This requires the natural gas company to survey the buildings and determine whether the area is equipped to receive the service before they grant official approval. This process has not yet taken place in Awlād ‘Allām, but many informal areas are not able to get natural gas due to the narrow streets, in addition to the fact that applicants must present documentation of legal tenure to the utility company, something that the ‘Izba’s residents do not have.

Residents also complained about water and wastewater infrastructure. Residents say that the area has been receiving basic utilities (water, wastewater, electricity) since the 1960s, but as with many old neighborhoods in Egypt, the infrastructure has not been adequately maintained leading to severe dilapidation and sometimes leakage – which over time can erode building foundations making them prone to collapse. Burst water and wastewater pipes also take place regularly which can flood the streets and sometimes even enter the homes. While there have been many requests by residents to the district manager to update and renovate the network, nothing has been done.

Other complaints include the lack of transportation within the area, the lack of solid waste collection (a nation-wide problem), and the lack of lighting in several streets making them unsafe at night. Certain streets are known as a haven for drug-dealers, and residents feel that something as simple as installing street lights could greatly reduce the problem.13

Another issue residents mentioned is the perception of Awlād ‘Allām among the residents of the formal and more affluent neighborhoods of al-Duqqī. While the residents themselves are proud of Awlād ‘Allām’s history as the core of al-Duqqī, and its role in protecting the al-Duqqī area during the revolution, many al-Duqqī residents still perceive the area as isolated and unsafe. This is, unfortunately, a stigma many informal areas in Cairo have to face. Several residents of al-Duqqī have mentioned that they would never think of entering Awlād ‘Allām because they believe it is unsafe. Even the media often represents Awlād ‘Allām in that same harsh light. For example, one recent news article says the following:

We [the reporters] were warned not to enter the area due to the presence of thugs and murderers who will not allow anyone in who does not belong there. But we are used to entering such areas, even though they are like minefields, we like to give everyone a chance to voice their concerns and struggles, even if that person is a criminal or thug.

This kind of rhetoric only serves to increase the stigmatization of places like Awlād ‘Allām, and it also makes residents less open to trusting outsiders. This became quite evident during fieldwork conducted in the area as residents were uncomfortable with photos taken of deteriorated buildings. This, they explained, was due to past experiences with reporters who would focus on such deteriorated areas and showcase them as representative of the entire ‘Izba.

Many of the problems described above are common in informal areas, and can often be traced to the lack of coordination between the various government agencies involved the managing the area. This issue is a nation-wide one and not restricted to informal areas, but it is even more exacerbated in areas where the ownership is disputed or ambiguous, as different entities claim or disclaim responsibility for the area. In Awlād ‘Allām’s case this includes: i) the al-Duqqī district manager who is at times cooperative and at other times says there is nothing she can do for an illegal area; ii) the al-Gīza governorate’s Urban Upgrading Unit which includes the area in its plan but cannot really undertake any upgrading without the cooperation of the EAA; iii) the EAA which refuses to sell the land to the residents at a price lower than market value; and iv) the ISDF which describes the area as unsafe and may be planning to make use of the area’s financial value to cover the cost of upgrading it.

Opportunities for Neighborhood Development

Today, Awlād ‘Allām is a functioning community, where many basic services are available including basic infrastructure, a youth center, and a public library. However, the area suffers from deterioration and lack of maintenance and residents are in constant negotiation with local agencies in order to deal with these issues. It is the government’s duty to provide services such as maintenance and infrastructure upgrading to Awlād ‘Allām’s residents as it does in other neighborhoods.

Despite all the obstacles residents face, there are many opportunities to spur the area’s development. Although there are not many NGOs in the area, some residents have recently organized into a ‘popular committee’ (lagna sha’biyya) to take on the task of solving the area’s problems. The committee coordinated with an informal youth-led local development initiative called Mahaliyyat Al-DuqqīwaAl-`Agūza(which is part of a larger national umbrella group) to conduct a community needs-assessment and prioritize the issues that residents would like to solve. Implementation began with residents’ highest priority: access to subsidized bread. The committee set up a kiosk and negotiated with the Ministry of Supply to allocate 6,500 loaves of bread per day to the area.

The popular committee is currently addressing the issue of access to health services, another high priority of the residents. The group is in the process of making arrangements with the owner of a vacant building to host a health center, and arranging with a hospital to provide volunteers for the center.The group also periodically checks for infrastructure that needs upgrading or roads that need paving and then they approach the district manager for redress. When the district manager does not respond, the committee employs other pressure tactics such as visits, phone calls, etc.

Simultaneously, the popular committee is also working on reaching a solution regarding land ownership and tenure ambiguity. Currently the popular committee is preparing to undertake a comprehensive housing survey in cooperation with the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights to substantiate further negotiations with the EAA with accurate data. It is also exploring possible legal channels through which to pressure the still uncooperative EAA.

‘IzbitAwlād ‘Allām, as one of the residents said, is “an area filled with good-spirited people.” The residents take pride in the fact that despite all their struggles throughout the years and despite their stigmatization as a crime-hub during the 2011 revolution the residents left their homes to protect the surrounding embassies and buildings. Looking at the al-Duqqī area through a Google Earth snapshot, `IzbitAwlād ‘Allām seems to be a pocket of informality in the heart of a well-ordered neighborhood. But the reality is that Awlād ‘Allām is one of the earliest neighborhoods of today’s al-Duqqī. Such self-built communities constitute the norm in much of the city, as western style planning was initially only imposed on targeted areas. Ironically, one of the original areas of al-Duqqī is today depicted as an illegal community, undeserving of the same standards of government attention and finances as its surrounding neighborhoods.

This highlights an important question that is relevant to almost every district in Greater Cairo: How should planners approach pockets of poverty in the midst of upscale areas? The approach in Cairo seems to be to segregate the city’s poor from the rich by pushing them out of upscale districts into areas where the land holds less value. In fact, this has been one of the core criticisms leveled against the Cairo 2050 plan, which has been developed as a future vision for Cairo. Viewing neighborhoods through the lens of their financial value rather than their social function seems to be the dominant strategy not only for Awlād ‘Allām but for the city as a whole, including – according to some analysts – downtown Cairo. Recognizing the social function of property entails acknowledging the impact of property use on the larger community, that property owners have obligations to serve the community, and that the burdens and the benefits of the urbanization process should be distributed in a just way.

Unfortunately, until the state decides to actively legalize the situation of ‘Izbet Awlād ‘Allām, its residents will continue to struggle for recognition of their right to adequate housing and their right to be part of the city.

Useful Links:

Awlād ‘Allām’s residents are yelling at Mahlab. أهالي عزبة أولاد علام يستغيثون بمحلب

‘Izbit Awlād ‘Allām got lost among embassies and towers عزبة أولاد علام تاهت وسط السفارات والأبراج

1.The word ‘’Izba’ means estate.

2.One scholar differentiates between informal, semi-informal, and ex-formal, and according to his definition of each category Awlād Allām should be defined as a semi-informal area. Ahmed M. Soliman. “Typology of Informal Housing in Egyptian Cities,” International Development Planning Review 24, no. 2 (2002).

3.The ISDF produces yearly reports that map all unsafe areas across the country.

4.It is not surprising that the Information Decision Support Centre listed the population as only 10,000 residents since the population of informal areas is often grossly underestimated in official figures.

5.El-Sherif stated that al-Duqqi hosts four haphazard/informal areas in total which are: Awlād Allām, Bīn Al-Sarayat, Dāyir Al-Nahya, and Masakin Al-Sikka Al-Hadīd.

6.More information about the concept of Waqf and its comparison with English trust laws can be found here, and more information about the Awqāf laws in Egypt can be found here and here.

7.The Waqf system can apply to various types of property and is not restricted to land, but this article will focus on land since it is of direct relevance to the case of Awlād ‘Allām.

8.Waqf property can be one of two types: i) The first is charity trust (waqfkhayry), and these are properties that the donor – known as the Wāqif – has donated to the Ministry of Awqāf and can generate income for charity purposes. The donor cannot specify a particular charity to which the property’s income would go, but rather the EAA becomes the sole entity responsible for distributing the income to different causes as it sees fit; ii) The second is private trust (waqfahly) which allows individuals to specify particular recipient(s) to receive the income generated by the endowed property, a process that takes place under the administration of the AwqāfAuthority. This type was abolished by Egyptian law in 1952, and thus the only type of Waqf recognized today is charity trust

9.This type was also abolished by Egyptian law in 1953. Until the late 1950s it was possible to gain tenure by adverse possession on land administered by the Awqāf if residents could prove they had lived there uninterrupted for 33 years. However, this was alsoabolished by Egyptian law in 1957. Eventually these laws were all compiled into Law No. (43/1982) which provided a legal basis on which residents living under ḥikr tenure could purchase the land and become legal owners.

10.The area is listed in the Informal Settlement Development Facility 2013 report as land owned by “central agencies.”

11.The ISDF has four levels of “unsafety” for different areas. Level one refers to life-threatening areas (such as those on a cliff prone to rockslides), level two refers to structural deterioration and buildings prone to collapse, level three refers to public health threats such as those that lack water and sanitation, and level four refers to insecure tenure.

12.A policy note on informality by the American University in Cairo (2014) explains Egypt’s slum development financing strategy as follows: “The current financial model for slum development is that the central government, through ISDF, finances the governorates with loans that should be repaid out of the slum development ‘revenue,’ which is expected to come out of land sales. It is assumed that there will be cross-subsidy; the revenue of projects for strategically-located slums can be used to fund projects where revenue is not expected.”

13.Documentation of a survey by the Mahaliyyat Al-`Agūzawa Al-Duqqī initiative which works in the area.

Comments