Al-Karāma Libraries Initiative, Khatwa Library, Dār al-Salām

A gap between residents of “informal” areas in Cairo (estimated to make up over half of the city’s population) and those living in “formal” areas is widening due to decades of discourse and policies that have entrenched prejudice and exacerbated inequality. Cairo’s urban poor have been deprived of access to adequate housing and basic services. They have also been deprived of a less obvious right and what some may consider only secondarily important: access to culture, in the form of educational materials, books, literary expression, and sufficient cultural spaces and activities. In attempts to address this gap, various initiatives have been founded with the aim of improving cultural life and education outside of schooling, and offering multi-level life-long learning opportunities. One of these is Al Karāma Libraries Initiative, launched by the Arabic Network for Human Rights Information (ANHRI). It proactively tries to improve the educational and cultural resources of informal areas by creating and managing small public libraries and interacting with local communities to promote a reading culture among youth and adults alike. The Initiative’s first library, named “Khatwa” [Step],opened in the Dār al-Salām area, south of Cairo on May 14, 2012.

The Situation before the Initiative

Dār al-Salām is an unplanned area in the larger Dār al-Salām district, neighboring al-Ma`ādī, al-Basātīn and Miṣr al-Qadīma that suffers from a lack of public facilities and basic services. As is the case in many of these areas that lack basic amenities, there are also no local public libraries or public spaces, where people may engage in different educational and cultural activities. Most spaces and activities in the area are commercial.

The only cultural service provided was through a mobile library, which used to stop by the metro station in Dār al-Salām on a weekly basis, allowing people to purchase or borrow books.1 Since the January 25 Revolution, however, Dār al-Salām’s residents no longer spot this mobile library in their area. Therefore, Khatwa library is, in effect,the only space of its kind in the area, providing its services daily and free-of-charge.

The Beginnings of the idea and its Development

ANHRI’s Al-Karāma Libraries Initiative decided to establish five public libraries in five different areas in the hope that these spaces would enable individuals to read, learn and expand their horizons and empower them to bring about change in their communities.ANHRI believes that “a well-informed and educated person has the ability to understand and defend his rights and to help develop his community”. Areas selected were marginalized, disadvantaged areas where ANHRI had contacts willing to cooperate in setting up the libraries.

Finding a “conventional” space to house the initiative’s first library proved difficult in the chosen area of Dār al-Salām. ANHRI transformed a ground floor cafe in one of the area’s most crowded streets into the Khatwa library. Despite its limited space, the design accommodates different types of users and accommodates talks and discussions, film screenings, and theater performances for children. The staff reached out to students and youth in neighborhood schools and computer centers and teachers were invited to visit the project. The project also contacted and solicited visitors from community associations, political parties and local authorities in addition to distributing flyers and hanging banners in the neighborhood.

Towards the end of 2012, ANHRI opened the second branch of al-Karāma libraries in the city of Zaqāzīq, and three other branches in Ṭura, Būlāq al-Dakrūrand Khanka between February and July 2013. With the establishment of each library, ANHRI has sought to extend the initiative’s geographical reach.

Resources and Sources of Funding

In November 2011, the Roland Berger Foundation in Germany awarded Mr. Gamal Eid, founder and Executive Director of ANHRI, the “Roland Berger Human Dignity Award” for his human rights activism. He dedicated the prize money to the initiative to cover founding costs, rent,utility bills and salaries.The libraries set up by the initiative employ a limited number of paid staff and seek the assistance of volunteers from the community to organize workshops and talks for the library users. As for books and stationary, the libraries depend on donations in kind and request of people wishing to make monetary donations to provide the libraries with books instead.

Assistance and Obstacles

In order to improve its services to library users, the initiative worked with civil society organizations such as Bāshkātib and the Ministry of Youth and Sports to expand its activities. The initiative had previously sought to offer its support and renovate the Al-Baḥr al-A’zam library, with the vision of transforming it into a culture center similar to the popular Sāqyat al-Ṣawī Cultural Wheel (a culture center in Zamālek founded in 2003), but they did not receive a response from the Ministry of Culture. In light of this experience and longstanding cultural policies (or the lack thereof), the initiative neither expects nor wishes to have substantial support from the Ministry of Culture or other governmental bodies as such support, it is thought, will come at the expense of the its independence and efficiency.

With regards to obstacles, the initiative faced a few at the beginning of the project. Members of the community were somewhat suspicious and questioned the project’s purposes, its sources of funding and whether the services provided were really free of charge. Given the dominant discourse after the January 25 Revolution that labels dissident voices as “foreign agents” and problematizes initiatives’ foreign funds, ANHRI fully expected their effort to be met with skepticism. To gain the communities’ trust, they made sure that they had contacts in the different areas before setting up the libraries and when faced with queries, they answered them honestly and in clear and simple terms. The initiative’s political and religious neutrality and the availability of many different types of books conveyed that the libraries were established for the benefit of everyone and as a result, the libraries have drawn in many people. Some community members in Dār al-Salām did not initially welcome the idea that boys and girls would be using Khatwa at the same time but the library has, through its service to the community, earned itself a reputation for being a respectable place.

Since the library offers all of its services free of charge, it does not have any revenue streams, making it completely dependent on in-kind donations for its resources. Their financial dependency on the monetary prize is one of the major challenges threatening the project’s sustainability.

Initiative Outcomes and Impact

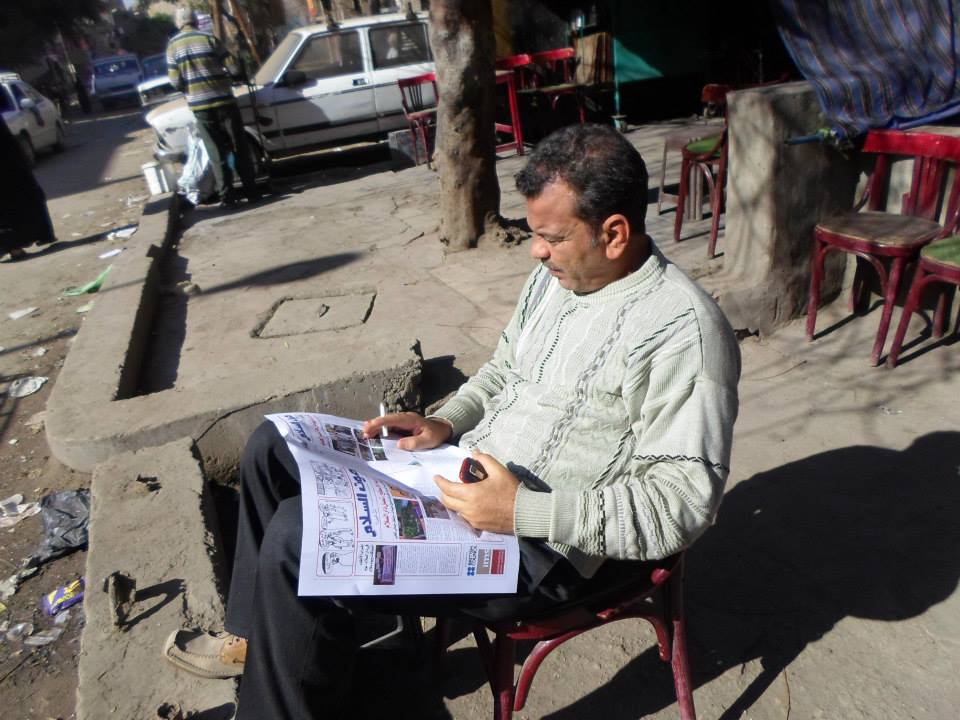

Khatwa library, in Dār al-Salām, now has approximately 60 daily visitors and more than 200 registered users. Since the beginning of the project, there has been an evident change in the social life of the community members. The library provided a much needed space, a forum for the community’s children and youth, where they can read books from various perspectives and participate in activities and communicate and share their ideas and aspirations for their area.In cooperation with Bāshkātib—an organization which empowers youth from marginalized areas byproducing and publishing local news—Khatwa held training sessions over a period of two months on journalism, creative writing, photography, and caricature drawing for twenty five of its users (aged between 12 and 17). In January 2014, equipped with their training, a group of youth launched “Ṣawt al-Salām” (Voice of [Dār] al-Salām), an occasional publication presenting the community’s news, opinions, problems and youth artwork. Ṣawt al-Salām was very well-received and the community appreciated that its editors were youth from the community. On the day of distribution, copies ran out in less than two hours, writes Maḥmūd Walīd, one of the youth who worked on the publication.

Community member reading youth publication “Ṣawt al-Salām”(© Khatwa Library)

The following month the library held a photography exhibition titled “Dār al-Salām through the Eyes of its Children.” The exhibition included several photos that had been taken by children and youth from the area to capture Dār al-Salām’s landmarks and details from its residents’ daily lives. The exhibition was also greatly appreciated by the community. A weekly cultural forum has also been a great success, attracting women and youth from the area.

“Dār al-Salām through the Eyes of its Children” Exhibition, January 31-February 6, 2014.(© Khatwa Library)

Sustainability

Social Sustainability

In light of the volatile political environment over the past few years, the initiative’s lack of political affiliation protects it from the stigma of being associated with a controversial political ideology or party. After the January 25 Revolution, libraries bearing Mubārak’s name or affiliated to the Integrated Care Society (ICS)were burnt, closed down, or they were forced to change their names.2 For example, in 2011, a mob set fire tothe ICS

Economic Sustainability

The prize money emanating from ANHRI’s work, which has been the initiative’s sole source of funding, was expected to cover the costs of the libraries for four years. Yet, since the beginning of the initiative, people have offered their support in a myriad of ways, stretching the resources of the original funding. On occasion property owners reduced rent prices andmaintenance workers volunteered to help the project.People have donated approximately 10,000 books to the initiative to date. Such immense support has lowered expected costs, meaning that ANHRI now has enough money to keep al-Karāma libraries open for an additional two years.

Opportunities for Repetition and Future Plans

ANHRI’s initiative has garnered wide interest from people across the country. Youth from al-Manṣura and Upper Egypt, who wanted to implement al-Karāma’s idea in their hometowns, contacted the initiative and ANHRI supported them by offering them guidance and donating books. Others contacted ANHRI, offering property to be transformed into libraries, such as those that the initiative had already established. If resources (financial and personnel) allow, the initiative hopes to establish its sixth library in Upper Egypt, in the near future.

The initiative believes that its libraries need not be grand and ostentatious to fulfil their role in the communities they serve. It is the libraries’ resources and the quality of service, which are of upmost importance. The libraries are simple yet active and effective. This non-materialistic, people-centered vision of what the libraries should look like has made the libraries relatively easy and cheap to establish and has played a great part in the project’s success. This vision coupled with continued enthusiasm from the greater public could certainly lead to the establishment of more libraries.

TADAMUN’s Viewpoint

Access to an active and dynamic public library (or a cultural space) may be overlooked as a secondary concern when discussing problems affecting communities in informal areas. However, as is shown by the impact of Khatwa in Dār al-Salām, encouraging young people to write, photograph their communities, express themselves, and produce local media in their own physical space empowers them to be agents of change, even if on a small scale. Khatwa has brought youth together and encouraged them to work as a team. In offering spaces that support acquiring knowledge and self-development, Khatwa along with the other libraries established by ANHRI could potentially inspire these communities to bring about change on other levels.

Moreover, demand for such spaces and resources in communities such as Dār al-Salām is only increasing as its youth are better educated, more connected to social media, and more mobile. Many Cairenes living outside of Zamālek regularly make an effort to attend Sāqyat al-Ṣawī’s events and to participate in its activities despite the center’s location. Sāqyat al-Ṣawī has, for a long time now, been one of Cairo’s few active and accessible cultural spaces. Initiatives other than al-Karāma such as Alwān w Awtār, Artellewa and the Darb al-Aḥmar Arts School also have become locally popular and successful, further proving that people appreciate access to cultural spaces and resources, which enable them to take up a wide range of enriching activities, whether reading or performing. The passion and commitment shown by various initiatives is praiseworthy and inspiring. However, the number of people living in informal areas and the magnitude of deprivation necessitates the planning and implementation of these types of projects on a larger scale.

During the Nāṣir and Mubārak administrations, projects aiming at improving access to cultural spaces and resources across the society and nation were indeed implemented. Tharwat ‘Ukāsha, the Minister of Culture (1958-62) and (1966 to 1970) during the Nasserist period established cultural palaces in different parts of the country. Another prominent example is Sūzān Mubārak’s highly publicized “Reading for All” campaign, launched in 1991, which made selected books affordable and as of 1993, had set out to establish “Libraries Everywhere” (“Maktaba fī kol Makān”). The Integrated Care Society (ICS) and Mubārak Public Libraries (now Miṣr Public Libraries) established public libraries in several areas including popular and informal areas. In March 2014, Al-Zāwya Al-Hamrā’ (a mixed lower income area of public sector, private sector, and informal sector housing) became home to Miṣr Public Libraries’ newest branch.

In spite of such efforts, access to cultural spaces and resources remains far from equitable. This failure could be attributed to the state’s attitude towards culture.The state conceives of culture as a means rather than an end in itself; its value lies in nation-building and legitimating the regime in power (arguably until today). The Ministry of Culture’s vision, articulated on its website, suggests that cultural policy should foster nationalism. It is worth noting that when the Ministry of Culture was first established in 1958, it was the “Ministry of Culture and National Guidance.” The state has shown a long-standing preference for mass media as the medium for culture dissemination as radio and television are more influential tools of mobilization and indoctrination compared to libraries and museums. In the recently proposed cultural strategy written by a committee headed by writer and researcher Al-Sayyid Yāsīn, the aversion to religious extremism is ranked as a priority.

As long as issues of identity and religion dominate the discussion of culture and culture continues to be seen as a tool for political control and ideological hegemony, it is highly unlikely that government projects will bear fruit. The perception of culture is key. If culture is a tool to achieve aparticular aim, it would make sense for governments to establish and maintain a monopoly on its production. Policies which promoted cultural diversity via books, photos, or theater would probably be discouraged in that case. On the other hand, if culture is perceived as a human right, the question will change from “How do we achieve this aim?” to “How do we ensure that citizens enjoy their right?” and how can communities provide both resources for rich, diverse, cultural and educational environments, as well as places to house them.

In previous Egyptian constitutions, culture was acknowledged as a “service” to be provided. The issue of access was first addressed in the 1971 constitution but only in geographic rather than socio-economic terms. In the 2014 constitution, however, Article 48 identifies culture as a “right” and emphasizes culture’s accessibility. Article 16 of the 1971 constitution dealt with inequality within the country, whereas, Article 48 is more comprehensive because it implies that inequality must be redressed, within the country or within the city, for those with means and without them.

Article 48 of the 2014 Constitution:

“Culture is a right for every citizen. The State shall secure and support this right and make available all types of cultural materials to all strata of the people, without any discrimination based on financial capability, geographic location or others. The State shall give special attention to remote areas and the neediest groups.

The State shall encourage translation from and into Arabic.”

Building on the notion of culture as a “right”, the National Culture Policy Group (NCPG)’s outline for a new cultural policy proposes several changes, necessary for a rich and dynamic cultural life, accessible to all Egyptians. The NCPG, set up in 2010, had presented its outline to the parliamentary Committee on Culture, Media and Tourism in March 2012, a few months before the parliament’s dissolution. The outline’s recommendations include an increased budget for the Ministry of Culture, the decentralization of culture and the revision of laws constraining cultural activities. The NCGP also recommends that the government should support and encourage the establishment and work of independent organizations.

Khatwa’s success lies, to a large extent, in how the initiative views the beneficiaries, its understanding of their needs, and its perception of culture as a right. Dār al-Salām’s residents (or those living in other areas where al-Karāma has established libraries) are not seen as an illiterate and uneducated mass that should be culturally “reformed” to contain a potentially threatening political or religious ideology but instead as individuals who have the right to a public space and to resources that allow them to explore the meaning of their lives, imagine and create their cultural worlds, in a variety of ways. This view, which is very much grounded in a human rights framework, led to the creation of a new accessible, inclusive, and vibrant cultural and educational space, personified by al-Karāma Library Initiative, but there is still room for many more philanthropic and community efforts.

USEFUL LINKS:

Cultural Policies in Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Palestine, Syria and Tunisia: An Introduction. (2010). Boekmanstudies, Culture Resource (Al Mawred Al Thaqafy) and European Cultural Foundation (ECF).

http://www.racines.ma/sites/default/files/Arab%20Cultural%20Policies%20by%20Al%20Mawred%20.pdf

El-Gamal, Mahā. (2014, February 4). “Bāshkātib”: Saḥāfa Mujtama’iyya fi Al-Aḥia’ Al-Sha’biyya b Miṣr. [“Bāshkātib”:Community Journalism in Popular Areas in Egypt]. BBC.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/arabic/middleeast/2014/02/140203_egypt_bashkateb_journalism.shtml

Khatwa:storefront library. (2012, August 6). Cairobserver.

http://cairobserver.com/post/28828325897/khatwa-storefront-library#.VBb0mPmSygY

Kitāb lil-Mufakkir al-Miṣry ‘Abd Al-KhāliqFārūq [A book by Egyptian Thinker ‘Abd Al-KhāliqFārūq]. (2010, December 10). ANN.

http://www.anntv.tv/new/showsubject.aspx?id=17340#.VAwH0vmSygZ

Maktabāt Al-Karāma Al-‘Āma [Al-Karāma Public Libraries]. Video Al-Karāma.

http://elkarama.anhri.net/?page_id=241

Wahba, Magdy. (1972). Cultural Policy in Egypt. UNESCO.

http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0000/000011/001193eo.pdf

1. The mobile libraries project is a project of Dar al-Kutubwa-al-Wathaʾiq al-Qawmiyya[ Egyptian National Library and Archives], which started in 1984 and came to a halt in recent years, mainly due to security concerns.

Ahmed El-Hawary.(2013, April 17). “Al Maktabāt al-Mutanaqela”..Mashru’ mohm [Mobile libraries..an important project stopped out of fear over“responsibility”]. Al-Maṣry Al-Yawm.

http://www.almasryalyoum.com/news/details/305219

2. The Integrated Care Society (ICS) is a non-governmental organization founded in 1977, which was chaired by Suzanne Mubarak.

State Information Service. 2009. Integrated Care Society.

http://www.sis.gov.eg/Ar/Templates/Articles/tmpArticles.aspx?ArtID=2463#.U8ZQrPmSygZ

Featured Photo from Khatwa Library

Comments