‘Izbit Al-Haggāna

“If there is a problem with one of the teachers they punish them by sending them here.”

“Our children are embarrassed to say they are from ‘Izbit Al-Haggāna. And if they do say it, their friends mock them and say, ‘Where is this strange place?!’”

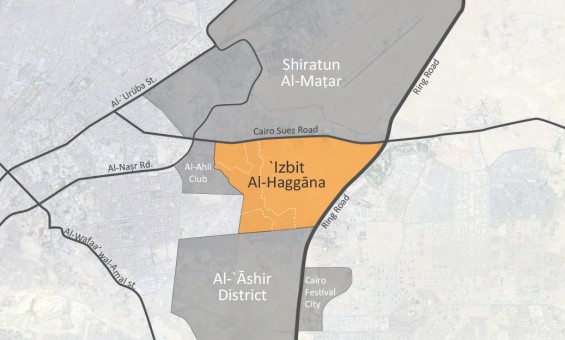

Such sentiments are not uncommon in Cairo’s informal areas, which are depicted too frequently in popular culture and elsewhere as havens for criminals and deviants. When President Gamāl Abdul Nāṣer and his urban planners established Naṣr City in the 1960s, it is doubtful that they expected it to include an area like ‘Izbit Al-Haggāna (hereafter referred to as Haggāna). Today, Naṣr City is home to numerous ministries, upscale shopping malls, and some of Cairo’s biggest luxury developments are nearby. It is not, however, a purely upper-class district by any means. East Naṣr City district consists of twenty-one sub-districts (shiākha) that host around 570,000 residents from across the socio-economic spectrum.1 One of these sub-districts is Haggāna, which arguably constitutes the most marginalized sub-district in East Naṣr City.

Haggāna is one of Cairo’s more well-known informal areas, perhaps because millions pass by it every day on their way from Heliopolis (Miṣr Al-Gadida) and Naṣr City (Madīnat Naṣr) to the Ring Road via the Suez Road. Located under the well-known Kilo 4.5 bridge, it is commonly known as the 4.5 Area.2

Most people hear about Haggāna before they see it and these rumors usually keep people away, fearing the supposed safety risks of visiting “the worst informal area in Cairo.”3 In an attempt to steer clear of such stereotypes, this article tries to answer the question: What is Haggāna actually like from the perspective of its residents?

‘Izbit Al-Haggāna in Numbers

Governorate: Cairo

District: East Naṣr City

Area: Approximately 750 acres (3 km2) (Bremer and Bhuiyan, 2014)

Population: Estimates vary from the grossly underestimated 39,432 by Egypt’s statistical agency CAPMAS (2006) to over one million by local non-governmental organization (NGO) Al-Shihāb Institution for Comprehensive Development.4 Today Haggāna is considered by author Mike Davis to be one of the world’s “mega slums” who estimates the population at one million (2005).5

The Story of ‘Izbit Al-Haggāna (Founding and Development)

The Armed Forces owned the piece of vacant desert land which became ‘Izbit Al-Haggāna and used it to house the army’s camel corps (which is the translation of the word ‘Haggāna’). Some researchers claim this arrangement occurred as early as the 1930s (Bremer and Bhuiyan, 2014). Settlement was concentrated in the northern part of the area adjacent to the Cairo-Suez Road.

Many of the camel corpsmen were originally from Upper Egypt and Sudan and they built one-story stone structures with mud ceilings, which were typical of their former homes (Al-Shihāb, 2006). Eventually the Haggāna soldiers were allowed to pay a fee in exchange for building additional dwellings for their families, but the area remained a military zone. The British largely housed their soldiers in Naṣr City during the British occupation of Egypt (MNHD, no date). After Egypt’s 1952 revolution, a new real estate boom in Cairo developed vacant land for residential and commercial purposes. In 1959, President Gamāl Abdul Nāṣer established the General Organization of Madīnat Naṣr by decree (later renamed Madīnat Naṣr for Housing and Development [MNHD]) and transformed the desert area between Heliopolis and the rest of Cairo into what it is today.6

‘Izbit Al-Haggāna’s strategic location attracted construction workers, domestic workers, and many other working-class groups seeking to benefit from the new employment opportunities offered by the booming Naṣr City district (Al-Shihāb, 2006). Egypt’s informal sector then grew quickly in the 1970s and 1980s due to internal migration to the urban areas, oil remittances from Egyptian workers in the Gulf, and the paucity of affordable housing. Haggāna’s lower-priced housing and easy access to the rest of Cairo continued to attract new residents, as did the eventual establishment of a public bus station at the area’s northern border.7 The settlement process began initially through squatting and later progressed into a complex system of illegal subdivision and sales, resulting in conflicts and physical altercations and the emergence of what some called a ‘land mafia.’

The Place and the People

While the Naṣr City district was built on a grid network of streets, Haggāna has narrow, winding roads and buildings in close proximity to each other. Although Haggāna is an informal area, it is listed as one of the sub-districts of East Naṣr City district on the Cairo Governorate website. A visit to the area shows that there are many street signs, but Al-Shihāb NGO claims that the residents named all the streets and financed and erected the signs themselves.

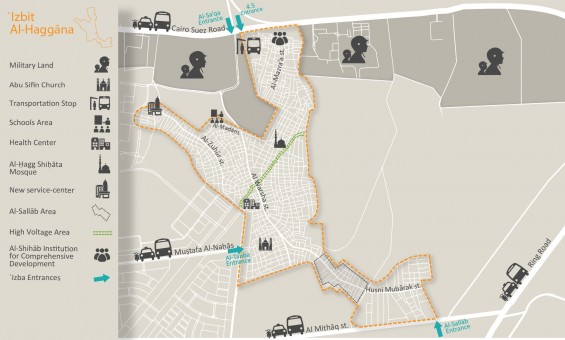

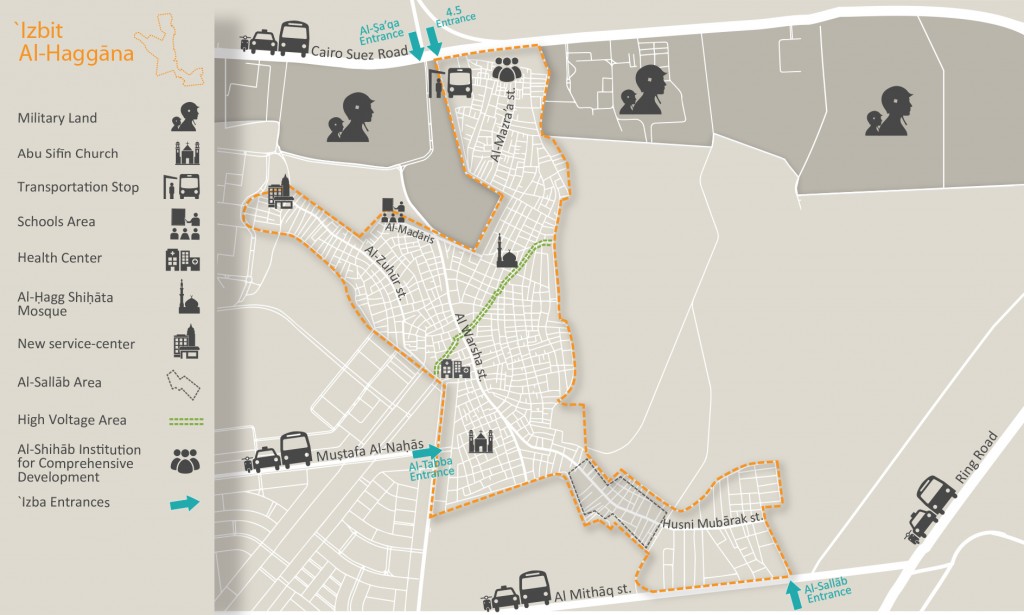

Geographically, the area is surrounded on all sides by military land and facilities (Bremer and Bhuiyan, 2014). The area has four main entrances, two at the area’s northern border (on the Cairo-Suez Road) called the 4.5 entrance and the Al-ṣa‘qa entrance, one at its western border called the Al-tabba/District 10 entrance, and one at the south-east border called the Al-sallāb entrance (see map below). There are a number of points through which one can enter Haggana but they are not well-known and tend to be used only by residents or people who know the area very well.

Local NGOs have divided the geographical area into four parts referred to as Area 1, Area 2, Area 3, and Area 4. This division is unofficial but is widely used by researchers and the NGO community.

However, the different parts do not serve any particular administrative function, and do not have clearly delineated boundaries that are agreed upon by all, and different parties often disagree as to where one area ends and another begins. The areas with the most consensus among local NGOs and residents are Area 1 which lies at Haggana’s northern boundary and encompasses the 4.5 area, and Area 4 which lies at Haggana’s southern boundary and encompasses the Al-Sallab area. High-voltage electricity cables cut through Haggāna (see map below) and some residents live under these cables, and this is one of the few areas in Haggāna where one can still find shacks. The area under the cables is referred to locally as the Al-ḍaght Al-‘āly (the Arabic term for high voltage) and it is the poorest area in Haggāna.

Residents often describe Haggāna’s geography is using its main streets. These include Al-warsha Street (north-south), Al-mīthāq Street (east-west), Al-madāris Street/area (northwest-southeast), Al-mazra’a Street (north-south), Al-ẓuhūr Street (east-west), ʾUhud Street, Al-ṣa‘qa Street (which is adjacent to vacant land owned by the armed forces and is also the site of the schools area), and Husni Mubārak Street (north-south).

Haggāna has many landmarks that are important to its residents, perhaps the most important of which are Haggāna’s bread-distribution kiosk and the bus station at the Kilo 4.5 area next to Haggāna’s main entrance. This busy station, established in the 1970s, is the terminus for many official bus lines, as well as informal microbuses and minibuses, making it convenient for travel around Cairo. There are bus stops at other parts of Haggāna’s borders, such as the Al-tabba stop at the western border, but none are major stations like the Kilo 4.5 station. The main mode of transportation within Haggāna is via tuk-tuk (motorized rickshaw) or pick-up trucks.

Important landmarks for the residents include a health center near the Al-tabba area in the west of Haggāna, and its three schools: one small private school on Al-ḥudūd Street near an army camp (Al-ḥigāz Primary School), and two public schools in the Al-madāris area (Al-mo’taz Billāh Primary School and Salāḥ Al-dīn Preparatory School). All three schools are to the east of Haggāna, and there are no high schools (secondary schools). Moving towards the south-east we find Haggāna’s main bakery called Furn ’Ali Sālim and a well-known coffee shop called Qahwat Filfil. In the south-eastern part of Haggāna are warehouses belonging to prominent businessmen Moṣṭafa and Aḥmad Al-sallāb. The Al-sallāb family is well-known throughout Cairo for their pseudo-monopoly of the building supply sector. A number of their outlets are situated in the Naṣr City district and two of their main warehouses are in Haggāna. Moṣṭafa Al-sallāb was a Member of Parliament (MP) in 2010 from the East Madīnat Naṣr district and much of his campaigning capitalized on Haggāna as a voting bloc.

Most buildings in Haggāna are residential with some commercial activities on the ground level such as workshops, coffee-shops, and convenience stores. Building density is high and the side streets are very narrow, but main streets average about five meters wide. The area includes shacks made from basic materials, ten-story high-rises made from reinforced concrete, and everything in between. Shacks are mostly concentrated in the high voltage area. A new service-center run by the armed forces was recently set up to serve Haggāna’s residents in the area’s Western part.

Other landmarks used by residents include the area’s many NGOs, civil society organizations (CSOs), and charities. Al-Shihāb Institution for Comprehensive Development is a Cairo-based NGO that has been active in Haggāna since 2001, in Area 1. Caritas, another NGO is located in Area 2, and Al-Mo’ez NGO, which is better known for its popular chairman and local resident Samīr Duko, is in Area 3. Other well-known NGOs include the ‘Imarat Al-insān Foundation and the Nūr Al-mashriq Organization. Mosques also sponsor many charities throughout Haggāna, as do other organizations.

The religious make-up of Haggāna’s residents reflects that of Egypt. The majority are Muslim and about 10% of the population is Christian. Most of the area’s Christians originally come from Al-minyā governorate in Upper Egypt and for a while lived in semi-closed groups near the church. However, integration with the greater community has increased over the years.

Mosques and churches constitute well-known landmarks in Haggāna. The most prominent mosques in Haggāna are Al-ḥagg Shiḥāta Mosque, Al-Hedāya Mosque, Suhaib Al-Rūby Mosque, and Shaykh Nazīr Mosque. The main church in al-Haggāna is the Abu-Sifīn church which follows the Eastern Orthodox (Coptic) denomination of the majority of Egypt’s Christians. According to one study there is another church referred to simply as “the Sudanese church and school.” This is a Catholic church and serves the population of Sudanese refugees in Haggāna.

The influx of thousands of Sudanese refugees began during the mid-2000s. Al-Shihāb NGO estimated that they included 4,500 families by 2009, concentrated around the church in the southern part of Haggāna. The area also hosts a small number of Somali refugees and has recently become home to hundreds of Syrian refugees in the wake of the war in Syria.

While it may seem that Haggāna is a melting pot of sorts, many communities are somewhat isolated from others. The relatively recent demographic changes have caused some tensions in the area. One researcher described the occurrence of disputes between Egyptians and Sudanese in 2007 in Haggāna as relentless (Le Houérou, 2007). These tensions prompted some NGOs to undertake projects to foster integration and address discrimination. According to Al-Shihāb NGO, relations have calmed in recent years, but there is always the concern that they may be reignited with the arrival of other groups of refugees and the economic downturn facing the country.

As for Haggāna’s Egyptian population, there are many tightly-knit communities of people that come from Upper Egypt, particularly the Al-‘Awāmeya and Al-Ghawaṣa families which constitute the two largest clans in the area and hail from the Upper Egyptian governorates of Suhāg and Qina. In Haggāna’s early years, many residents associated with others that came from the same village or governorate, but today, due to inter-marriage between families, social relations are much more integrated.

In Haggāna there are not many places to socialize. Many youth prefer not to socialize in certain local coffee-shops, since they perceive them as hubs for delinquents. Thus, it is common for youth to spend their leisure time outside Haggāna. Women have even fewer public spaces in which to socialize, but sometimes can be found in a small garden outside the area across from the 4.5 entrance or outside the local public schools while waiting for their children.

Residents of all communities typically value parts of their communities more highly than others and Haggāna is no different. Generally, they consider Area 1 the more prosperous part of Haggāna perhaps because it constitutes Haggāna’s original settlement. It is better-serviced with higher quality housing units, wider streets, and is safer (although residents generally consider Haggāna to be safe except for a few pockets in the community). Area 1 is also the most stable area regarding family conflicts as it has a higher concentration of older families who play a role in conflict resolution (Al-Shihāb, 2007). Other favored areas are Al-ẓuhūr and Uhud streets in Area 2 because contractors recently tore down older buildings and replaced them with high-rise apartment buildings, populated by more prosperous and “respectable” people. It is clear that many residents associated the respectability and safety of a particular area with the social and educational background of its residents, highlighting some internal class dynamics and stigmatization. Another factor that is associated with personal safety is proximity to army facilities, since nearby military personnel provide a sense of security to residents when walking through such areas. Outside Area 1, the remainder of Haggāna includes areas with poorer services, narrower streets (some are as narrow as 1-2 meters wide), and a larger number of one-story traditional homes.

The two areas considered by many residents as the worst in Haggāna are the High Voltage and ‘Ghagar’ areas. The High Voltage area, as mentioned in the beginning of this article, is named after the high voltage electricity cables which tower above people’s homes (some are barely higher than people’s roofs). The close proximity of the homes to the cables have caused fires and electrocutions (especially when it rains), and some residents also blame the high voltage wires for certain diseases prevalent in the community. Residents consider the High Voltage area the most deprived part of Haggāna. This is due to two reasons: first, it is located in the middle of Haggāna and government utility network plans – such as water, sanitation, electricity and natural gas – start at the edges of Haggāna and progressively move inwards. According to residents, the servicing schemes either start from the north or south, but always stop right before they reach the middle of Haggāna, which is where the High Voltage area lies. The second reason is related to its designation as an “unsafe area” by Egypt’s Informal Settlement Development Facility.8 This classification implies that the government will forcibly evict and relocate the residents and destroy the buildings, and thus some government agencies are reluctant to service this particular area (or perhaps only use the ISDF classification as a pretext for ignoring the area). See, for example, this statement from the Cairo Governorate which declares that a certain maintenance service will not be provided to the homes around the high cables because the governorate is planning to ‘remove’ them.

The second area highlighted by residents as the ‘worst’ part of al-Haggāna is the Ghagar area. The Ghagar area lies in Haggāna’s north-west, near the schools area. Residents of this part of Haggāna are garbage collectors and other residents often claim they are “rough people who don’t trust anyone.” Ghagar is the Arabic term for ‘gypsies’ and is often used in Egypt as a derogatory slur against people considered petty thieves or vulgar. This is a common use of the term “gypsy” around the world and thus sometimes certain groups may be labeled as gypsies when, in fact, they have nothing to do with ethnic gypsies. The term “gypsy” actually refers to a set of ethnic groups including the more well-known Roma in Europe, and the lesser-known Dom gypsies who are found in the Middle East and North Africa. One local NGO claims that the residents of the Ghagar area are actually Egyptian ethnic gypsies who are descendant from the Dom ethnicity. According to the Dom Research Center for Middle East and North Africa Gypsy Studies, many of Egypt’s estimated 1 million Dom gypsies (over 2 million according to The Joshua Project) recently began migrating from Upper Egypt to Cairo in search for economic opportunities.9 They work in isolated or less respected occupations such as garbage collectors, street cleaners, beggars, and sometimes entertainers.10 Residents could not recall any negative experiences with the area, but simply explained that they preferred to avoid it due to the “unfriendly” nature of its people. This once again highlights the type of internal stigmatization that takes places among different groups in the community.

‘Izbit Al-Haggāna: The Good and the Bad

Cairo’s informal areas tend to be depicted in the media and official circles in solely negative terms, but the fact that these areas have attracted millions of residents indicates that there must be some advantages to living there.

For Haggāna’s residents, in addition to offering affordable shelter, something quite scarce in Cairo, one of the biggest advantages of Haggāna is its strategic location offering easy access to the rest of Cairo. Haggāna is also relatively well-serviced. There are water, sanitation, and electricity utilities, and as part of the government servicing plan, some parts of the area are also being provided with natural gas. This is not to suggest these utilities are perfect—there are many issues related to the quality and reliability of these services—yet they are considered reasonable especially when residents compare them to many areas outside of Cairo (particularly Upper Egypt, the former home of many Haggāna’s older residents).

Finally, the area’s strong social ties are highlighted by many residents as being a big advantage. Many extended families live near each other, as do clusters of people from the same village providing a sense of familiarity and security. There is not a single police station in the area, despite the residents’ continued demand for one, and thus they depend on self-policing, aided by the community’s social capital.

However, according to its residents, the area suffers from many disadvantages as well. An outsider may assume that insecure housing tenure would be highlighted as the most problematic issue, but they complain the most about the stigma they face as a community, solely because of where they live. This stigma is manifest in two ways. First, outsiders view their community as a haven for criminals. Residents complained that not only are their children mocked for where they live, but they are sometimes rejected from schools outside Haggāna when the administrators discover where they live. This, needless to say, is an extreme form of discrimination and segregation where Haggāna children are seen as only fit for Haggāna schools. The school system exacerbates this even further by posting teachers in Haggāna’s schools as a form of punishment when a teacher commits a mistake. In response to such discrimination, some residents have been discussing the idea of choosing a new name for the area, despite the fact that Haggāna’s name is deeply rooted in its history. The alternative names being considered are ones that would inspire pride among residents, and some suggest removing the term “’Izba” altogether which is associated with slums throughout Cairo (e.g. ‘Izbit Khairallah, ‘Izbit Awlād ‘Allām).

The second way in which stigma is manifested through the distribution of public resources. As one of East Madīnat Naṣr’s sub-districts, residents of Haggāna expect to receive their fair share of municipal funds, particularly in regards to schools, health services, social spaces, police services, and better maintenance of infrastructure. Residents highlighted the example of the area’s educational needs, as Haggāna’s schools continue to suffer from severe overcrowding despite holding double sessions (morning and evening classes), and yet the district’s educational budget will usually be spent elsewhere and people from Haggāna will be told to wait until new funds are available. Residents have been demanding new school construction for years, but Haggāna rarely wins these budgetary battles. According to residents, they receive the leftovers of the district budget after all of the other sub-districts have used the funds for their needs.

The inequality in distribution of municipal funding is further exacerbated by the undercounting of Haggāna’s population. According to the Cairo Governorate website, the total population of East Madīnat Naṣr district (which includes Haggāna) is 571,465. This is quite odd because the population of Haggāna on its own is estimated to be between 500,000 and 1 million, far more than the population estimate for all of East Madīnat Naṣr. It is common for government agencies to undercount the populations of informal areas.11 The latest (2006) census data from CAPMAS states that Haggāna has a population of 39,432, and a government report about informal areas lists Haggāna’s population as 37,090 (IDSC, 2008).12 As a result of this gross underestimation, a neighborhood with potentially around 1 million people is receiving budget allocations for just 39,000 people, something that deprives it of its fair and equitable share of services and budget allocation, and exemplifies how it is treated as a second-class area.

Generally, residents feel that government officials are only concerned with Haggāna when there is a ministerial visit or during election times.

“When there is new funding coming to the municipality for education do you think they start with our schools? No! They start with Abbas Al-Akkad and other areas in Madīnat Naṣr and when it comes to our schools they say wait until next time we get funding.” – Haggāna resident

Some people within the community have been calling for the government to recognize Haggāna as a separate district in the same way that Madīnat Naṣr was divided into two after it grew tremendously. Residents feel the area’s size and population warrants its own municipality and dedicated budget allotment and that a separate municipality would attract more deserved attention to Haggāna. Creating a ‘Izbit Al-Haggāna district with a dedicated municipality office could potentially contribute towards the resolution of another important issue: tenure insecurity. Although the original corpsmen settled on the land legally, none of their descendants remain and none of the area’s current residents have any kind of formal tenure or documentation. In this sense, Haggāna’s legal status is similar to many of Cairo’s informal areas on desert land since those residents also hold no form of formal tenure. The Haggāna residents themselves are the first to admit that all settlement there was done via squatting.

However, this informal status is coupled by tacit acceptance of the area from government agencies who have not attempted to ‘regularize’ the situation. While there have been a few clashes with government security forces, there have been no official attempts to evict residents, nor have there been any attempts to legalize their situation. One reason why it has been so difficult to resolve this issue is related to the complex ownership of Haggāna’s land.13 Some of Haggāna’s land is owned by the armed forces, while another part is owned by MNHD. There are also parcels of land that these two entities have been fighting about in a court case since 2001. According to some local NGOs, there have been informal discussions with MNHD about the possibility of legalizing tenure in exchange for a fee, but these discussions have not yet resulted in any action. There have been no similar discussions thus far with the armed forces regarding the land it technically owns, which people have squatted upon. Solving the situation will require a great deal of negotiation among the stakeholders involved and the government should do its part to protect Haggāna residents’ right to adequate housing.

Conclusion

There is no way to justify that a group of people are treated differently solely because of where they live. Unfortunately, this is the case for many informal areas in Egypt, where popular discourse in Egypt portrays informal/unplanned spaces as disorderly and dangerous, as opposed to planned, orderly, and, perhaps most importantly, modern. As Ismail (2006) explains, “within this frame of representation, the ‘ashwa’iyyāt [slums/informal areas] are produced as the city’s internal ‘other.’ They are the sites of crime, drugs, illness, degradation, immorality, decay, and decline.” The residents of ‘Izbit Al-Haggāna object to the stigma they face as part of an informal area. But whether or not others consider their neighborhood to be a legitimate part of the city, Haggāna’s residents will continue to fight for better treatment and a fair and equitable share of public services.

1. Founded by ministerial decree in 1987, the Naṣr City district split into East Naṣr City and West Naṣr City in 1999.

2. Heliopolis used to be at the boundary of Cairo during the 1960s and Haggāna was exactly 4.5 kilos from that original boundary.

3.The article opens with the statement: “Thuggery. Thievery. Drugs. Rape. You are Now in the Heart of ‘Izbit al-Haggāna.”

4.Researcher Sarah Sabry confirms that visiting the area is sufficient to deduce that the CAPMAS figure is a “severe underestimation” (2009). She provides an overview of the conflicting data regarding al-Haggāna’s population. Results from the CAPMAS 2006 census states that al-Haggāna’s population is 39,433. Estimates by other entities are much higher such as 200,000 (GIZ), 400,000 (Soliman, 2004) and one million inhabitants according to several local NGOs, which makes it the 14th largest slum in the world according to Davis (2006).

5.It is important to note, though, that Davis does not provide a source for this figure but rather simply states that “scores of sources were consulted.” (Planet of Slums, 2006, p.29)

6.Although MNHD began as a public company, it was offered on the Egyptian Exchange through an Initial Public Offering (IPO) in 1995, and Beltone Private Equity acquired 30.88% of the company in December 2006. Today, it is a major real estate company with projects all over Greater Cairo.

7.As with many public bus stations around Cairo, an informal minibus and microbus station eventually emerged next to the official station, making it a multi-service transportation hub.

8.The ISDF produces an annual map of unsafe areas in Egypt and classified the homes around the high voltage cables as “Degree 2 Unsafe” (i.e. the physical structure of the home is unsafe) and “Degree 3 Unsafe” (i.e. posing a threat to the public health of its residents) in its 2013 report.

9.More can be learned about Egyptian gypsies from this article.

10.Interestingly, the Ghagar residents are not the only gypsy group in Haggāna. As part of the influx of refugees from Syria into Egypt, groups of Syrian gypsies have made their way to Cairo and settled in al-Haggāna. One article claims that Syrian gypsies have come to Cairo in the hopes of eventually making it to Alexandria and finally to a European country that is more tolerant of the gypsy way of life). It is, however, unclear whether these Syrian gypsies have settled in the Ghagar community alongside their Egyptian counterparts, or if they are in other parts of Haggāna.

11.Government agencies are known to undercount the poor in general. For a deeper analysis of this see “Poverty Lines in Cairo: Underestimating and Misrepresenting Poverty” (Sabry, 2009).

12.The report states that area population data was retrieved from the governorates.

13.In academic slum typologies Haggāna is often grouped with areas that lie on “state-owned desert land” (cf. Sims, Soliman). But this label is misleading as it gives the impression that the state is simply one monolithic body, whereas the truth is that the Armed Forces, the Cairo governorate, and the formerly public MNHD all operate with varying agendas and stakes in Haggāna’s land.

Comments