Painting Initiatives: Can They Make Egyptian Cities Better Places to Live?

Over the past few months, Egyptians using the social media platform Facebook have witnessed the emergence of many “painting” initiatives, such as Color Zone in Suez, Coloring a Grey City, Hanlwenha, Cairo Dish Painting Initiative and Mashrou al Saada.

Most of these initiatives were led by students interested in beautifying Egyptian cities by adding color and images to public space such as walls, staircases, infrastructure, or fences. Other painting initiatives have emerged since 2011: the Cairo Dish Painting Initiative, for instance, is a project which focuses on painting privately-owned objects such as satellite dishes and views painting as an opportunity for self-expression. Another initiative, Paint Cairo, is not only interested in painting facades of informal settlements situated at the outskirts of Greater Cairo, but also in plastering them in order to challenge the stigma associated with their unfinished look.

This article will discuss three initiatives that attempted to make a difference in how residents visually experience their city namely Cairo Dish Painting Initiative, Coloring a Grey City and Paint Cairo. The article will then explore the potential of implementing these types of projects at a larger scale.

The Situation Before the Initiatives

To many people, Cairo is a “grey city” whose aesthetics are compromised by air pollution and the many run-down buildings in the urban core or the unfinished red brick and concrete buildings in informal settlements, which encompass more than 60% of Cairo’s population. By changing the physical aspect of Egyptian cities through color, painting initiatives are designed, not only to have a positive impact on people’s well-being and quality of life, but also to inspire people to improve their environment.

The Beginning of the Idea and its Development

Cairo Dish Painting Initiative: Artellewa – an art space located in the neighborhood of ‘Arḍ al-Lewā which provides cultural education in form of art exhibitions, lectures, film screenings and workshops to local residents – invited Jason Stoneking, a Paris-based American artist and author, for a three-month residency in late 2014. Stoneking saw the dusty satellite dishes of Cairo’s rooftops as a beautiful metaphor for “an individual communication channel from one family’s home to outer space” (!) and an opportunity for Cairenes to express their own individuality and creativity.

Coloring a Grey City: A group of ten students from the Faculty of Fine Arts, Helwan University launched this initiative and other students and volunteers from outside the university soon joined them. They wanted to add a splash of color to the overwhelmingly grey city in an attempt to combat the visual impact of pollution and the desert climate. By beautifying the city, they hoped to improve people’s mood and inspire them to take care of it.

Paint Cairo – Maṣrbel-’Alwān (Egypt in Colors) was launched a few months after the 2011 Revolution by architects from the consulting firm Takween Integrated Community Development.1

Takween’s founders began the initiative as a way to give back to communities such as `Izbit Khayrallāh, volunteering their time and resources to improve the aesthetics and conditions of informal areas. Using the skills gained through their experience working on the al-Darb al-Āḥmar Revitalization project initiated in 2000 by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC), the Takween team beautified many building facades, using limestone to plaster them (instead of cement) and painted them in light colors with lime wash to reduce heat absorption.2

Requirements for Implementation

Sources of funding:

The Cairo Dish Painting Initiative and Coloring a Grey City required little financing, just enough to buy a few cans of paint. For the former, Jason Stoneking purchased painting supplies when he was involved in the painting and when he was not, residents purchased supplies themselves.

For Coloring a Grey City, the first projects were self-funded by the team, but as the initiative grew, they received support from a professor at Helwan University who helped the students contact paint companies to sponsor their work. They found a sponsor – the painting company SCIB Paint – who not only provided the paint, but also advised the team on color choices.

Due to its bigger scope, Paint Cairo required a larger budget. The Takween team estimates that the average amount needed to scaffold, plaster and paint the facade of a four-story building (which has an average 14-meter height) is 11,000-15,000 EGP. Due to the limited funds available, structurally deteriorated buildings that required significant structural rework were not selected.

Interaction with Government and Residents:

The painting initiatives required authorization from both private residents and public officials. Coloring a Grey City required a permit from the Giza and Cairo Governor as well as the support of district chiefs, who not only authorized the projects, but helped implement them as well. For example, Coloring a Grey City painted a public staircase and the district chief ensured that the stairs were cleaned before the group painted them. The Dean of the Faculty of Fine Arts, Sayed Kandil, helped the students obtain the necessary permits.

A Letter Signed by the Dean Sayed Kandil Sent to the Qaṣr An-Nīl District Chief (Source: Coloring a Grey City Facebook page, 2014)

Paint Cairo received support and authorization from the Informal Settlements Development Facility (ISDF), a public agency dedicated to upgrading informal areas, and it also had to work closely with residents to obtain their permission and cooperation to implement the project.

The Cairo Dish Painting Initiative focused exclusively on private properties and therefore only required the approval of their building inhabitants/owners. Artellewa’s close partnership with the neighborhood’s local community was a critical factor in residential trust and support for the American artist, Stoneking.

Participation:

Painting initiatives usually welcome the participation of residents and/or volunteers during the implementation phase.

Coloring a Grey City and Cairo Dish Painting Initiative made use of social media platforms to gather volunteers. However, the latter gave priority to resident involvement considering the difficulty of gathering more than a dozen people on a single roof. The initiative’s ultimate goal was to encourage residents to express their creativity by the painting of their own satellite dishes. However, many residents expected the artist Jason Stoneking to paint their satellite dishes himself.

The Paint Cairo team required the participation of the local community in the implementation process, not only in the choice of treatments and colors, but also through in-kind contributions to the project cost. By training residents about the different uses of lime in building techniques, they raised awareness among residents about the positive environmental effects of using lime-based plastering techniques.

Initiatives Outcomes

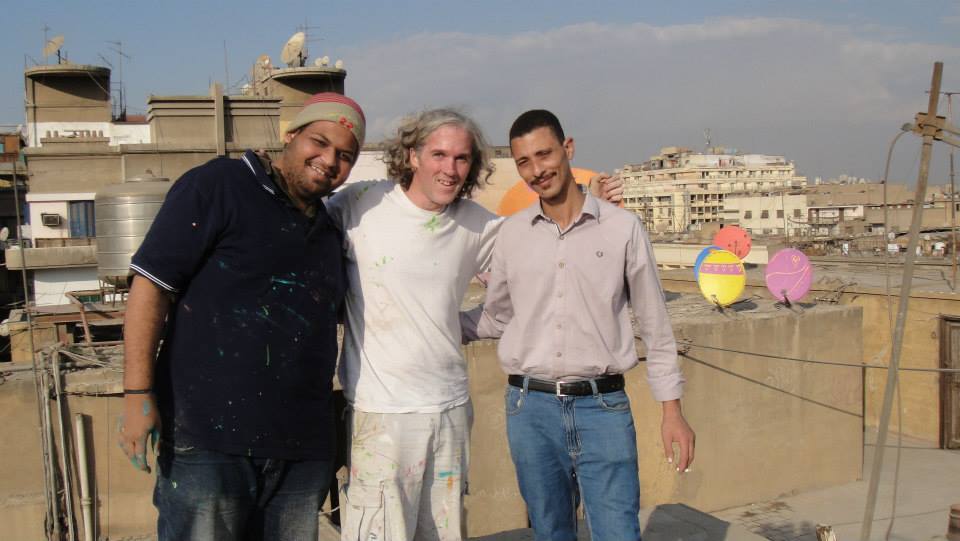

Cairo Dish Painting’s artist, Jason Stoneking, began by painting the satellite dishes situated at the top of the Artellewa Art Space building before expanding his work to other rooftops within the ‘Arḍ al-lewā neighborhood and other neighborhoods throughout Cairo. In most of the buildings, local people joined him in the painting. More than a hundred dishes were painted on about eleven rooftops, seven of them by Stoneking himself with the help of residents in the neighborhoods of ‘Arḍ al-Lewā, al-Marg, al-Duqqī and Downtown Cairo (Kodak building). The dishes on another three to four buildings were painted without Stoneking’s involvement.

On the Rooftop of the Artellewa Art Space (Source: Cairo Dish Painting Initiative Facebook page, 2014)

Stoneking and Other Volunteers at the Top of the Kodak Building (Source: Cairo Dish Painting Initiative Facebook page, 2014)

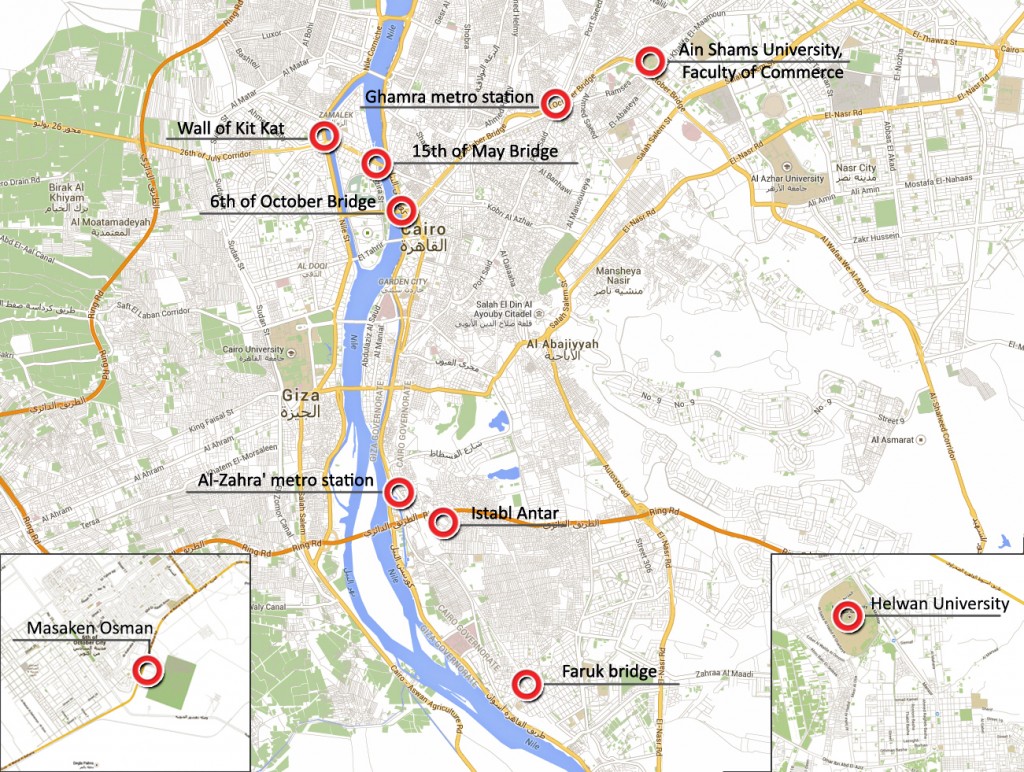

In January 2015, Coloring the Grey City painted more than ten areas including the stairs of 15th of May bridge, 6th of October bridge, Ghamrah metro station, Helwan University, Faculty of Business at Ain Shams University, Isṭabl Antar in `Izbit Khayrallāh and Masākin `Othmān in 6th of October City and walls of Kīt-Kāt, Fārūq bridge in Ma`ādī, and next to al-Zahrā’ metro station. The team also claims that their initiative inspired similar efforts in Shubrā al-Khaymah (the northern suburb of Greater Cairo), as well as in cities across several governorates such as al-Minyā, Manṣūrah, Alexandria, Suez, and Luxor.

The Stairs of the Ghamra Metro Station before and after Coloring a Grey City’s intervention (Source: Coloring a Grey City Facebook page, 2015)

A Wall of the Fārūq Bridge in Ma`ādī Painted in Partnership with Cairo Dish Painting Initiative (Source: Coloring a Grey City Facebook page, 2014)

Paint Cairo plastered and painted five buildings in `Izbit Khayrallāh in November 2011. In addition, following the completion of the pilot project, during the same year, 13 buildings were plastered and painted in Manshīat Nāṣir in partnership with Nebny Foundation.

An unexpected effect of the project in `Izbit Khayrallāh was its influence on public service delivery. Shortly after the building rehabilitation was completed, the government extended the sewage system to that area of `Izbit Khayrallāh. The project also had a positive financial impact for the landlords of buildings as they were able to rent for a higher price – from 100-150 pounds per month to 200-250 per month. The original tenants were seemingly not affected sincethey had old rental contracts. Finally, the project encouraged other residents in the surrounding area to renovate their building facades on their own.

Sustainability

The sustainability of these three initiatives depends on the capacity of their initiators to popularize the idea, mobilize volunteers and secure funding.

The overall aim of the Cairo Dish Painting Initiative is to popularize the idea so that people will copy the idea, without external organizers. Stoneking hopes that in the next five to ten years, Cairo will be known as the city of the colored satellite dishes. Nevertheless, at the end of his three-month residency in Cairo in December 2014, Stoneking learned that only three or four people had painted their own rooftop satellite dishes. This small number contrasts with the very large number of people (over 200) who contacted Stoneking to join his initiative. This demonstrates that individual interest in an initiative does not always produce successful results and that it may be more effective to channel these interests into a collective endeavor.

Coloring a Grey City’s long-term sustainability is heavily based on volunteerism and the financial in-kind contributions of the paint company. The project organizers easily attracted volunteers as people unaffiliated with the university joined them in the painting. In addition, the company lowered the project’s costs by donating paint. It also helped to extend the sustainability of the painted areas by providing better quality paint than the group had initially used.

Due to its higher cost and the technical skills needed to implement it, the large-scale implementation of the Paint Cairo initiative is more complicated. Hence, this model could be adopted by urban upgrading government institutions working in informal areas but not by residents themselves, even though they can, and are often willing, to contribute to the effort.

TADAMUN’s viewpoint:

Over the last few months, the public has become very interested in painting initiatives. Such interest has to be understood within the emerging re-appropriation of public space that began with the 2011 revolution, where citizens attempted to take ownership of city spaces and politically-inspired graffiti covered walls and fences in many areas of Cairo.

In addition, painting initiatives should be seen within an international context, where street art has become a way to beautify marginalized neighborhoods of cities around the world. One of the most celebrated examples, by Dutch designers, Jeroen Koolhaas and Dre Urhahn, is the Favela Painting initiative in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil launched in 2005 as well as the ‘Return to Identity’ program launched by the mayor of Tirana, Albania, Edi Rama, in 2000.

Understanding the Context: Painting initiatives, Graffiti and the Street Art Movement

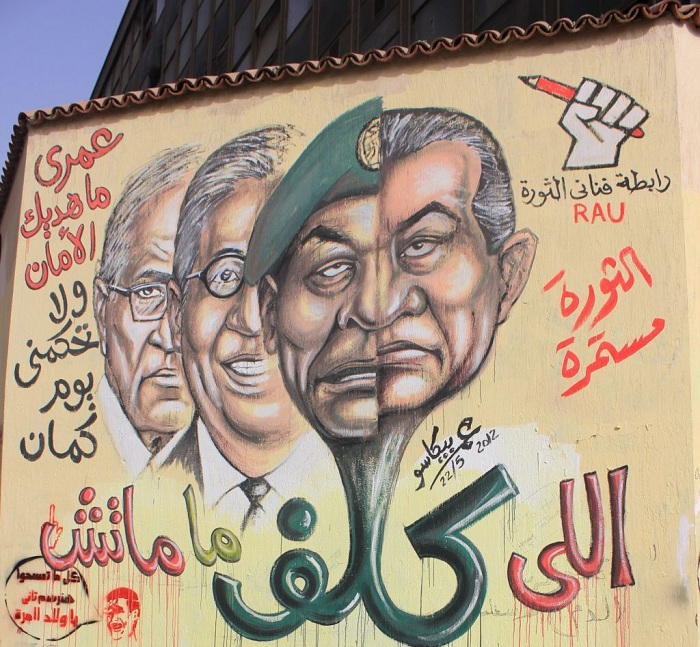

Before 2011, artistic forms of expression in the streets of Cairo were limited to professions of love (e.g. ‘Yassin+ Layla = ♥ ’), commercial stencils, religious pilgrims’ paintings and tags of one of the most popular Egyptian football clubs, El-Ahly (Klaus 2014). In these cases, capital “A” Art was not the first intention of the people who created these kinds of drawings or graffiti in public spaces. Urban art, understood as a deliberate artistic form of expression in public spaces outside traditional venues, emerged in Egypt following the 2011 Revolution. However, painting initiatives and graffiti are different in several respects.

The politically-saturated revolutionary graffiti was (and remains) subversive. It challenged authority and transgressed previous norms about discussing sensitive and controversial political, religious, and social issues. It usually carried a forceful political and social message, constituting a “home-made media” designed to challenge the conventional media (print and TV) (Sanders IV, 2012). Graffiti amplified and sustained the revolt by creating a public forum of opposition to political figures and institutions—former presidents Mubarak and Morsi, the security apparatus, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), the Muslim Brotherhood, etc. Graffiti from his period often supported certain public figures and memorialized martyrs, such as the victims of the Port-Said events where seventy-four ‘ultras’ of Al-Ahly football club died on February 1st, 2012 (Klaus, 2014).3

In contrast, much of the graffiti since 2013 has been supportive of the new regime and oppositional graffiti, when drawn, is quickly covered over by a new coat of paint.

Painted on the wall surrounding the American University of Cairo on Muḥammad Maḥmūd Street in September 2011, this Graffiti by Omar Picasso Criticizes the Mandate (taklīf) Given to the SCAF – and Especially its President, Marshal Tantawi – to Rule the Country after President Mubarak resigned (Source: Dawyer, 2012).

By contrast, painting initiatives are not subversive at all. Participants ask for authorization from public authorities to paint public property or restrict themselves to privately owned properties and cannot be misconstrued as acts of vandalism. Painting initiatives may have a social message as well, but the message is not a political challenge to authority, it is a challenge to society to see, understand, and improve the space around them. Hence, what is the actual effect of painting initiatives? The Favela painting initiative and the Tirana municipality experience provides us some insights in this regard.

The Impact of Painting Initiatives: Examples from the Favela Painting Project and The ‘Return to Identity’ Program in Tirana, Albania

The project developed by Jeroen Koolhaas and Dre Urhahn, or Haas&Hahn, began after they both first visited the neighborhood of Vila Cruzeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, to film a documentary about life in the favelas.4

Their original intent had little to do with the favela’s poor condition. They simply wanted authorization for a painting in a unique and challenging setting.

It was only after some time that they began seeing their project as a way to challenge the stigma these areas carry and address some of their most pressing issues, including poverty and crime.The public art projects, it was hoped, might attract other development projects and thus create new long-term sources of income for favela dwellers through increased tourism in the area, or possibly reduce the drug trade and crime, and in the long-term reduce social and economic inequality in Brazil.

In certain ways, the favela painting project was very successful. After producing a few paintings, Koolhaas and Urhahn started a crowdfunding campaign in the late 2013 through which they managed to raise over 100,000 US dollars in little over a month. Hence, they had the freedom and the opportunity to implement their initiative on a larger scale (Kolhaas and Urhahn, 2014).

This Painting Completed in Collaboration With Local Youth, Helped Teach Them a Creative and Employable Craft (Source: Design Boom, 2011)

Colorful Houses Painted by the Favela Painting Project in Santa Marta (Source: NY Post, 2014)

However, the expectations and overall effect of Favela Painting was contested. It seemed to offer fewer solutions to social and economic problems than it claimed. In the neighborhood of Santa Marta for instance, the sewage system problems have yet to be resolved. Likewise, not surprisingly, the drug trade and crime did not significantly decrease due to the initiative. Increased employment in the tourism sector has also failed to materialize. Romanticizing favelas by celebrating the life and vitality of their residents, the project may have had a counterproductive effect as residents are becoming increasingly disillusioned by such projects (Rahman, 2014).

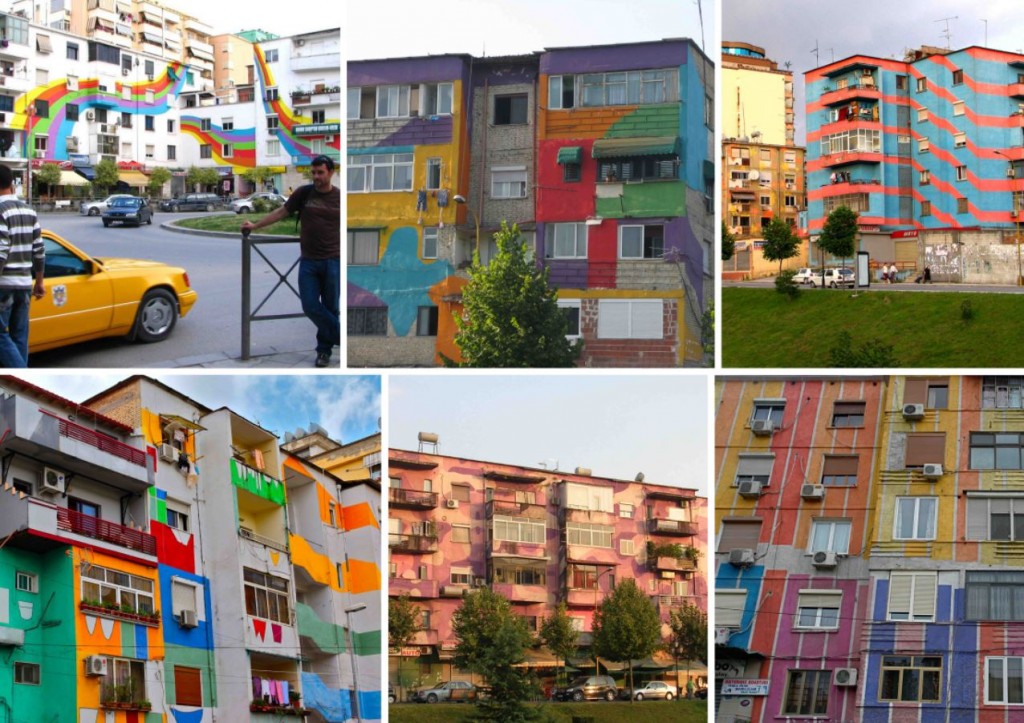

Overall, if painting walls, staircases, infrastructure, or fences may not have the social impact claimed, except as part of a comprehensive urban renewal policy, they are inexpensive low cost interventions that governments can use to demonstrate their presence to citizens and signal that there is positive change to come. Edi Rama, the former mayor of Tirana, Albania, utilized this approach with a facade-painting program in the early 2000s.

Albania was a communist country between 1946 and 1992 and one of the most isolated countries in the world. After the collapse of the socialist regime in 1992, and the weakening of the centralized economy and state, informal construction in Tirana exploded and people from the countryside began migrating to the city in large numbers. When Rama was elected mayor in 2000, the city’s public spaces had been swallowed up and the river that ran through the center of the city was choked with debris. The city was faced with many challenges, but since the Mayor had a very small budget a large-scale urban renewal project was out of the question.

Mayor Rama, a former art student, conceived the painting project as a temporary solution to “revive the hope that ha[d] been lost” as a result of years of communism, government neglect, and the degradation of the city and its public spaces (Rama, 2012). It was supposed to open a new kind of relationship between local government and residents by sparking a debate over the cityscape and its renovation (Triantis, 2010a and 2010b). Overall, the project attracted international recognition to the city and the Rama won the 2004 World Mayor Award (Pusca, 2008).

One of the First Repainted Buildings of Tirana, Albania (Source: Rudi.net)

Painted Buildings in the Albanian Capital (Source: Mynewcupofcoffee.com, 2014)

Interests and Limits of Government’s Involvement

Since 2013, the Egyptian government has been keen to upgrade the physical condition of some areas in Cairo. Over the past several months, the governorate has embarked on an urban renewal project in downtown Cairo, “the development project of Khedive Cairo”. Several buildings overlooking Tahrir Square in downtown Cairo, including the Mugamma` building (the biggest government administrative building in the country), have been repainted and others in downtown are underway. Following the creation of the Ministry of Urban Renewal and Informal Settlements (MURIS) last June, Minister Laila Iskandar announced that MURIS will begin painting building facades in several informal neighborhoods in the Cairo and Giza governorates including Manshīat Nāṣir, `Izbit Khayrallāh and al-Baḥr al-’A`ḍham. Finally, on December 8th, 2014 Egyptian President Abd Al-Fatah Al-Sissi met with Christine Zarif, the leader of a student painting initiative called Hanlwenha (which means literally “we will paint it”) together with a number of youth development associations. During the meeting, President Sissi praised the initiatives and stressed the importance of strengthening the role of civil society.

The government’s embrace of painting projects is not surprising since they are more visible and expressive projects and they are less expensive than installing or renovating infrastructure or improving public services. Some may find the government’s interest in these programs paternalistic while others may worry about the government’s appropriation of ongoing civil society projects. In addition, state involvement in painting initiatives may be counterproductive since they could lose their spontaneity and dynamism, which some argue guarantees their long-term sustainability. Coloring a Grey City, which depends on volunteers and the Cairo Dish Painting Initiatives whose ultimate goal is to allow residents to express their creativity, might lose their raison d’être if they become government-led projects. The Paint Cairo initiative differs since it was launched by architects who welcome state involvement in order to expand the scale of the project.

Overall, whether initiated by the government, volunteers or residents, painting initiatives can have a very positive social impact of painting initiatives: they represent an acknowledgement that the space or building is “worthy” of ornamentation and can be a vehicle for visual beauty—while helping to transform the ‘grey,’ dusty city. In short, these initiatives can expand the diverse ways residents experience their city and make it their own.

Works cited:

Klaus, Enrique. 2014. “Graffiti and Urban Revolt in Cairo“. Built Environment, 40(1), 20 pages.

Pusca, Anca. 2008. “The Aesthetics of Change: Exploring Post-Communist Spaces“, Global Society, Vol. 22, No 3, pp. 369-386.

Rahman, Fariha. 2014. “The Impact of Favela Painting“. Senior Inquiry High School Program, Paper 11.

Sanders IV, Lewis. 2012. Chapter 4: “Reclaiming the City: Street Art of the Revolution“. In Mehrez, Samia, Translating Egypt’s Revolution. The Language of Tahrir, The American University in Cairo Press, 143-182.

Takween. 2012. Paint Cairo Project. Concept Note, 15 pages.

Triantis, Loukas. 2010a. “Urban Change and the production of space: The case of urban renewal in Tirana (2000-2008)“. Tirana Workshop II: Interventions in former-state residential complexes, University of Athens in partnership with Polis University, 10 pages.

Triantis, Loukas. 2010b. “Colour politics and urban identities. A critical evaluation of the facade-colouring project in Edi Rama’s Tirana“. 10 pages.

TED Videos:

Koolhaas, Jeroen and Urhahn, Dre. 2014. “How Painting Can Transform Communities”. TEDGlobal, October.

Nasser, Marwa. 2014. “Coloring a Grey City”. TEDxPortTawfik, December 6th.

Rama, Edi. 2012. “Take back your city with paint“. TEDx Thessaloniki, May.

Related websites:

http://www.favelapainting.com/

http://www.jasonstoneking.com/

1. Takween Integrated Community Development is a partner of “TADAMUN: the Cairo-based urban solidarity initiative” along with the American University (Washington, DC). For more information, do have a look at the Partners page.

2. This project aimed to rehabilitate, through a participatory design approach, the al-Darb al-Āḥmar neighborhood, thereby complement the creation of Azhar Park, a 30-hectare park on the outskirts of Historic Cairo. For more information, please consult the article entitled “Post-revolutionary Urban Egypt: A New Mode of Practice”.

3. ’Ultras Ahlawy’ is a fan group of El-Ahly Football Club, the most prominent in Egypt, founded in 2007.

4. Favelas are shantytown located within or on the outskirts of Brazil’s large cities, especially Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. As in Cairo, houses have been built informally and few houses are finished i.e. plastered and painted

Feature Image from Coloring a grey city

Comments