Nahia Village Solid Waste Management

Despite its spot along fertile soils, near to Cairo with its services and job opportunities, and next to the town of Kerdassa with its carpet making industry and stonemasons, the village of Nahia (Kerdassa district, Giza governorate) nonetheless is completely neglected by the government. The village, despite the opportunities made available by its location in greater Cairo, proximity to the vital circulation of the ring road and connection with neighbourhoods like Boulaq al Dakrour through the long thoroughfare of Nahia St., suffers from polluted drinking water that has plagued its nearly 100,000 residents with high rates of kidney failure. Were you a resident of Nahia Seeking treatment for this, moreover, you would find a hospital that is itself swimming in sewage overflowing from faulty sewer pipes.

But where you would need to talk to the residents and learn about their lives to discover this, the problem that one cannot mistake even from brief inspection is the problem of trash spread and piled about throughout the village. The village of Nahia is not alone in this, it resembles in this problem the vast majority of other areas in egypt, particularly those rural areas falling along the edges of cities.

The residents of Nahia, however, haven’t sat waiting for someone to come and offer them the promise of clean streets; they have successfully demonstrated that management, treatment and recycling of solid waste doesn’t require substantial resources from the government or technical knowledge from academic experts; rather, all it takes is some organisation, effort and cooperation with the various parties involved, yielding practical lessons for those willing to learn them.

The initiative started by Nahia village for dealing with their trash and solid waste problem is worthy of serious respect and study, as they were able to devote the scarce resources of the village–both public and private–to the implementation of a sustainable project. Their success, moreover, does not end at the borders of their village, but they continue to extend their work to serve neighbouring towns.

The Situation Before the Initiative

Despite the fact that collection of solid waste is the clear responsibility of the government, in the countryside this role is neither carried nor are there even the mechanisms in place to do so. Garbage collection and transportation requires several stages that require planning from whoever would seek to do so. Dealing with trash requires an organised means of taking it from the house to the street and from the street to a collection point where it needs to be sorted and recycled. Besides those cities where the government has contracted private waste management companies (which have proven completely ineffective so far) to collect trash from dumpsters in the street, such companies do not operate in the countryside. In these areas, the role of the government is little more than providing trucks and bulldozers to pick up trash that has accumulated in the streets and canals, and this only when it reaches crisis levels hindering traffic.

Nahia village has been confronted by this trash problem just as every other village in the absence of a working system, with no other option but to throw their trash into the streets and canals until it reaches such a bad extent that the bulldozers are dispatched to remove the worst of it, the most that the local governmental unit would do. In order to fill this organisational and regulatory vacuum, the “Nahda [Renaissance] Foundation” of Nahia village undertook planning and implementation of a project to collect trash from homes to a duping site outside the village limits for collection and sorting. These are precisely the steps missing from the government’s system, and the initiative has been so successful that the government has perhaps realised this and conceded the use of its own bulldozers at this dumping site.

The Idea and its Implementation

The Beginning of the Initiative and its Development

The “Nahda Foundation” is a community organization in Nahia that was founded in 2011 that has organized the “Nahia Garbage Project” to collect and recycle solid waste on the level of the entire village. The project’s operations began 27 January, 2012, but the idea came much earlier. The idea itself arose immediately after the start of the revolution, amidst the formation of Popular Committees and fervor by ordinary people to participate in popular projects seeking to solve problems irrespective of the government’s involvement.

It was against this backdrop that a group of friends and acquaintances decided to start a community project for cleaning up Nahia, and so they instituted the Nahda Foundation (they claim that the similarity to the Muslim Brotherhood’s development plan, the Nahda Project, is purely a coincidence), and these friends became the steering committee of the Foundation. Despite the fact that the project is not tied directly to any political organization except for the individual affiliations of its members، perhaps what contributed to this establishment was that most of the members were tied to islamist poltiical parties and movements, or to the Muslim Brotherhood.

The Foundation decided on trash collection as a starting point upon realizing that this intervention, unlike most other projects related to infrastructure, would not require government intervention or significant resources. Currently the project serves the entire village and some neighborhing areas, and the Foundation additionally provides technical and institutional support to other villages seeking to repeat the project. Furthermore, the project has improved quality of life across the village (subscribers and nonsubscribers alike) and it would appear that even business owners are benefitting from the new system.

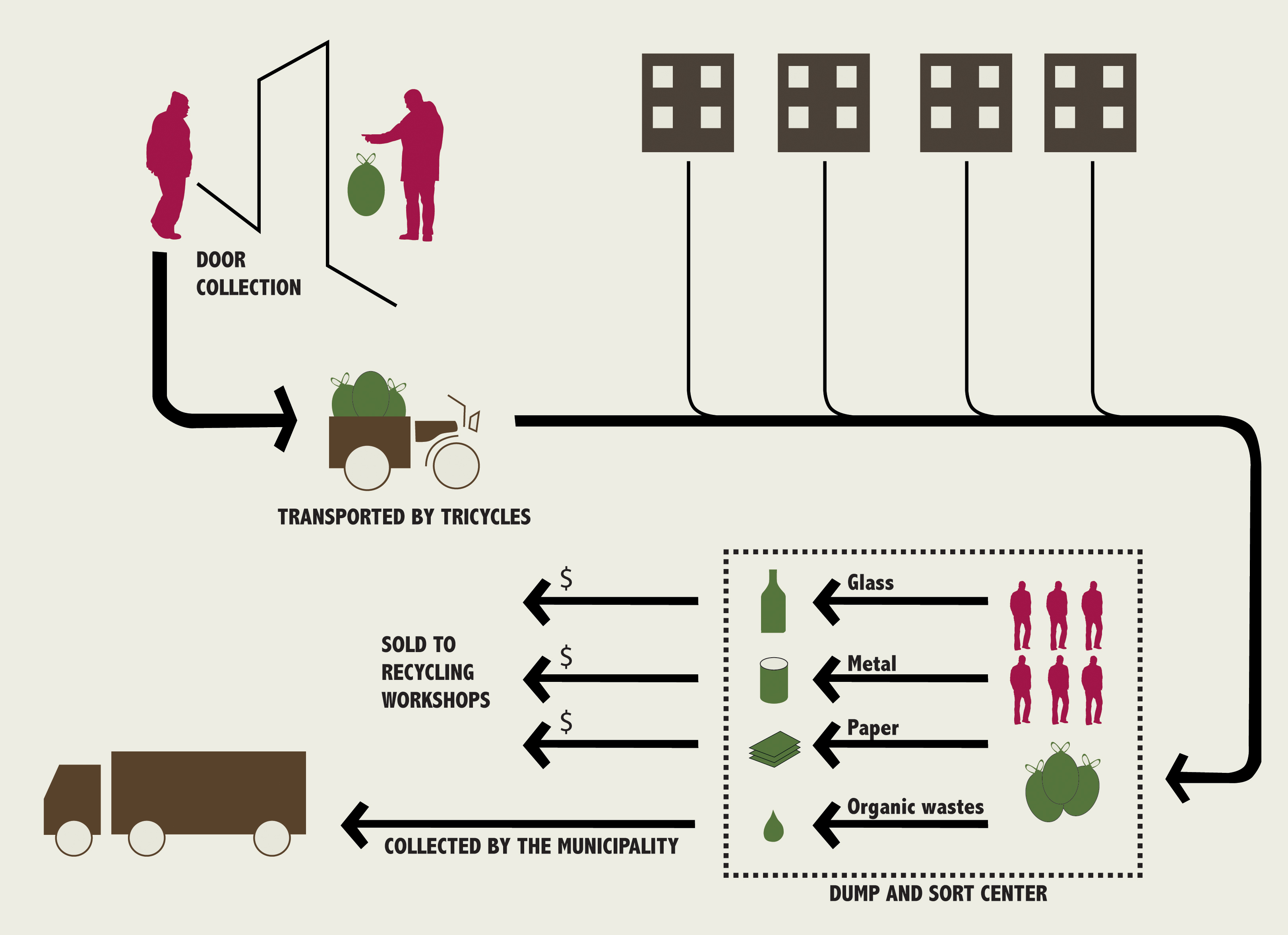

The project operates, in short, by using motorized tricycles sent along daily pickup routes, passing by each of the subscriber homes to collect trash and take it to the dumping site for sorting and separation of any items that have resale value or are recyclable, such as organic waste. Recycleable materials such as metal, glass and cardboard are sold to recyclers in order to raise revenue to supplement the project; the rest is removed by a truck sent at least once a day by the local municipal unit.

The people of Nahia do not pay a fee for trash collection as part of their utility bills, such as residents of cities like Cairo and Giza, rather members of the organisation collect the subscription fees as they pass by houses on their collection routes. The project, furthermore, also collects garbage from in front of several public and government buildings, such as the schools and hospital, at no charge.

Before it became well known locally, The Nahda Foundation began by first planning the project and undertaking feasibility studies and setting steps for implementation, and then subsequently decided to legalize its status as an Foundation in order to facilitate better coordination with the government. Legalization was particularly useful, perhaps necessary even, when the Foundation sought to obtain land for the dumping site, one of the essential components of the project. Initially, they used land in a canal floodplain owned by the Ministry of Irrigation informally; after negotiations and some pressure they reached a formal agreement with the Governorate to take control of this plot of land land for the use of the Foundation, not the project. It would not be possible to allocate the land directly to the project, as there is no legal framework for allowing an institution to contract with the government for a private initiative. After the allocation of the land they were compelled to build a perimeter wall around the area, as people had begun littering their own trash all around the site.

To this point, the Foundation remains the sole administrator and decision maker of the project, with a project manager from within the Foundation overseeing daily operations without any participation of neighbourhood residents in decision making processes.

Resources and Sources of Funding

The project’s startup required an initial plot of land for the dumping site to begin operations, the capital costs of walling in the land and purchasing equipment in addition to hiring about 23 workers to cover the 5000 subscribed homes, making up roughly 70% of the entire village. There was also, of course, the social capital needed to market and advertise the project locally. The management of resources began with a meeting of the foundation board and distribution of duties between them, subsequently seeking funding sources, loans and donations, and then outreach to other local organisations likely to cooperate.

Initial costs for the project were roughly 185,000 EGP, which the Foundation raised partially through zero-interest personal loans. Another large source of the initial costs came from in-kind donations, notably, the tricycles, which were donated by two charitable organizations who sought to participate (another four charities within Nahia refused, possibly for political reasons). It is worth mentioning that the price of the land is not included in the initial capital, as this was itself an in-kind concession by the government.

Currently the project does requires only its operating expenses, a monthly budget of approximately of 40,000 EGP, which is includes 27,600 in salaries for 23 workers earning 1200 EGP each (taking into consideration the adequacy of this amount to the worker so as not to have to sort garbage for him), stipends for the 6 workers of the municipality, a salary for the manager, and finally some money for maintenance and repair of the machinery. This amount comes from the monthly subscriptions (10-15 pounds per building per month depending on the size of the building) which total roughly 45,000 EGP monthly, meaning a 5,000 EGP surplus; this surplus is deposited into the foundation accounts directly, which are monitored and reviewed internally.

The primary funding for the project thus comes from the subscriptions; additionally, some revenue is made from selling recyclable materials but the type of household and agricultural waste produced in Nahia, as opposed to paper, glass or metal, is not terribly profitable in itself.

The project thus finds itself financially sustainable in its current form, not suffering from any material deficiencies, actually making money over expenses. This is in contrast to the first month of operation, however, where the project lost 11,000 EGP due to an insufficient number of subscriptions and having set the cost of subscription too low (initially half of current rates); the issue was quickly resolved however by leading a subscription drive in the community and adjusting the rates, leading to the current sustainable budget.

Assistance and Obstacles

The project does face several challenges, however, namely the reluctance of some to participate, preferring to throw their trash into the streets or the village canals, whether from unwillingness to pay or lack of awareness or apathy towards the health and environmental concerns this raises. Bizarrely even, the Foundation reports that nonsubscribers have even attempted to bribe the workers to take away their trash, offering more than the cost of a monthly subscription. Some of the lack of participation may be related to negative publicity that the Foundation has received due to its perceived ties to the Muslim Brotherhood. The project managers have attempted to curb littering in the village by filing legal complaints against people they find dumping trash in the canal or the street, but also less adversarially through awareness-raising and direct communication through village social networks. They have sought to point out the change in the level of cleanliness since the project has started to convince residents of the value of the project and clean streets.

Besides general issues of adoption, there are also issues related to the workers, who were for some time treated coldly or antagonistically by residents; this, according to the project manager, was most likely due to class reasons or stigma associated with dealing with garbage, yet the problem seems to solve itself gradually with time as residents become acclimated to the role that the workers are playing in keeping their streets clean of garbage. Moreover, the inadequacies and inconsistencies of the municipality in sending trucks and equipment to pickup the garbage has proven to be problematic; speaking to the head of the municipal unit, he attributed their deficiencies to a lack of diesel fuel rations from the Governorate. He noted as well the desultory pay given to employees of the municipality relative to the work asked of them, discouraging them from actually working and compelling the project to pay them stipends.

According to one of the foundation members, the organizational strengths of the project lie in the fact that it is run by a cohesive group of influential community members, able to provide the funding needed to run the project. The group is also characterised by its experience in management and administration, especially evident in their role in organising the work of the popular committee of the village that spread during the revolution in the wake of the security vacuum.

However, despite this experience, there are risks facing the project. For example, the Foundation has built strong bonds with the local municipal unit, but that relationship remains informal. There is no formal or institutional framework governing this relationship, and there would be nothing to stop the municipality from deciding to stop sending its trucks and equipment to pick up garbage from the collection point

Besides this, the perceptions of those who link them with the Muslim Brotherhood put them under the sway or risk of constantly changing political perceptions. This perception is related to one of the greatest potential weaknesses of the project in our view: the lack of community participation, both participation as pertaining to needs assesment (whether formal or informal) or any type of participation during the design and implementation phase (from the workers, for example). Furthermore, the organizers of the project have no intention to expand community representation nor do they see a problem with the current level of representation.

In order to internally assess the initiative’s activities and measure the extent of its success, the Foundation uses a tally of the number of subscribers and the amount of revenue generated by subscription. Additionally they are keen to measure project expenses and income, making sure that they will continue being financially sustainable. This assessment occurs internally and informally, without any regularised criteria or frequency.

Initiative Outcomes and Impact

According to the Foundation’s outlook, the project is highly successful, covering 70% of the entire village, and we ourselves noted an improvement in the cleanliness of the streets compared to images and videos from 2010. The entire village has benefitted from the project, and the more subscribers and fewer free-riders there are, the greater this benefit is to the village. Likewise, the project has benefitted the public buildings in the village by providing them with free cleanup services.

The village is cleaner today, and healthier, and relatively speaking there is greater coordination between the Foundation and the municipality; the police also have begun assessing fines against people littering and dumping in the streets at the behest of the Foundation, which is seeking to maintain the level of cleanliness in the village as well as encouraging people. The project initiators also have begun to consider the possibility of recycling their organic waste into fertilizer or fuel. Despite all this, however, until they are able to pressure or encourage the municipality to provide greater support, they will often be limited by a lack of equipment to remove the garbage from the dump site.

Sustainability

The project’s monthly revenues are paid directly into the accounts of the Foundation, and are currently being used to pay back the loans that were initially taking out. There are no threats currently to the sustainability of the project, as it has neither competition nor does it compete with any other economic activities activities, even providing employment opportunities for the unemployed of the village. Culturally, the project is relatively sustainable, however there remains the issue of the perceived goals of the Foundation and the political differences between its members and those who oppose them, which impedes the full support of the community and may have further negative impacts on the project. Environmentally, the project has not yet been able to inculcate a culture of separating recyclables from trash amongst members of the village, but thus far they have done this separation themselves.

However considering institutional sustainability, the Nahda Foundation directly manages the affairs of the project, and is itself composed of influential or well known community members. This gives it a certain amount of credibility and perhaps aids it in being sustainable, except if this preexisting social strata were to be shaken up it could easily threaten the project. That said the level of coordination with the government is promising, both in the deal that secured the land and in the arrangement for pickup of garbage from the main dump site, but even this remains uncontracted and informal, as opposed to the companies the government has otherwise hired to do the same job elsewhere.

Practically, however, the project is stable and sustainable right now, making a profit and not lacking in any material resources, but this could all be threatened without greater government recognition or formalization of their work which would give them both legitimacy and greater capacity for sustainability

Opportunities for Repetition and Future Plans

From the standpoint of their experience over the preceding period, those responsible for the project recognise the difficulty of their endeavour without accompanying awareness by the community in the village about the disadvantages of dumping garbage in the streets or nearby irrigation canals. Technically, the project managers now believe that that using trucks would have perhaps been better than the motorized tricycles, as the latter require constant repair. The project implementors realize now a possibility of recycling organic wastes into biofuel or fertilizer, and they plan to do so on their own site. The project managers have several desires going forward, including greater cooperation with the people of the village, and increased awareness toward environmental and public health issues. Additionally, they would like to see greater material support from the local municipal unit (more equipment), and would also like to obtain a formal contract with the government or municipality under which they would be the official body in charge of collection, allowing them to work across the entire village as a formally recognised entity. Finally, they would like more media attention to the project to help them expand their activities and obtain greater resources; some of the Foundation’s members have started trying to inform media of the importance to their experiences, but thus far they do not think there has been enough attention.

The initiative’s ambitions, furthermore, do not stop at the borders of Nahia alone; so far, the Foundation has transferred its own technical and institutional experience to neighbouring villages, including Birk al Khayam, at the request of residents of these areas who admired the experience of Nahia and sought to replicate it in their own communities. The Nahda Foundation has begun providing assistance to these neighbourhoods, either through directly implementing similar collection schemes or providing technical support to groups who would replicate the project themselves.

Beyond this, the project manager of the Nahia Solid Waste Project is himself considering starting a private trash collection company, for profit, in a new area (he notes perhaps a more urban area where there is more recyclable material thrown out). They believe that they can transfer their experience (technical and institutional) to other projects seeking to do the same in other areas, and according to the Project Manager, with the proper resources the initiative could easily cover entire governorates.

Tadamun’s Viewpoint

Doubtless, the Solid Waste Project in Nahia is not the only successful project in this area, without a doubt there are many similar initiatives in different regions in Egypt. Opinions within the village differ about the initiative, with some seeing it as an ideal solution to the garbage problem while others criticise it perhaps for practical reasons or due to competition between different political currents. Yet regardless of all this the experience is one worthy of attention and follow-up, due to the level of success it has been able to achieve in the village so far, not to mention the extent to which its initiators have been able to transport the idea to adjacent villages. Apart from the direct results of the initiative, there are several important points worthy of comment:

- The experience is characterised by the ability of those who initiated it with identifying the shortcomings of the government system of trash collection in the countryside and dealing with these shortcomings in order to reach a system which integrates the role of the Nahda Foundation with that of the state apparatus. Thus, the foundation has succeeded in shaping a role for itself that supplements the deficiencies in government performance, while making full use of the available capacities and resources of the local municipal unit They did so without competing with state institutions in performance of the service for the people of the village. This last point in particular contrasts in particular with many other initiatives that have failed to capture the available governmental resources and end up either competing with the state or facing shortfalls that doom these other initiatives. In the case of this initiative, the state has provided land necessary for the collection site, as well as dump trucks for taking trash to central landfills. All of these are resources that the initiative would otherwise be unable to obtain. For its part, the initiative has provided the collection of garbage from homes, and its community and administrative expertise in order to find a system that is financially sustainable, provides job opportunities to the people of the village, and, most importantly, is able to pick up the garbage in the streets of the village in a way that the government was never able to do.

- This point specifically calls on us to retying the relationship between the state and civil society institutions, and how each may supplement the other in the work of sound management of the few available resources that each is avail be to provide to the other. On the one hand, you do not need the state to the exclusion of the role of Civil society claiming the exclusive right to provide such services and then failing to do so due to lack of available resources. On the other hand, many civil society organisations make the mistake of trying to excusing the state of its responsibilities to society and citizens by creating institutions that are alternative, parallel systems to the role of the state, instead of trying to capture available state resources to fix a dysfunctional (but already existing) government system.

- This segues into another important issue, that of scale. The practice of government agencies in the last two decades has been to contract with large corporations from the private sector, both Egyptian and internationally, to carry out collection and management of solid waste. Many believe that trend arose from the framework of privatisation that the state adopted in recent decades. However, the truth is that the state seized this role from traditional garbage collectors (themselves private operators, but on a small scale). The state gave this role then to another private sector, the large scale, in clear prejudice against supporting small business and in favour of supporting large, capitalist companies . Though these companies may in fact have advanced techniques for management and collection of solid waste, this does not mean that these small entities, more numerous and more able to adapt to the needs of the community, should be crushed. We need both scales to work together, which is exactly what is being done in Nahia, and may be a main reason for their success.

- Another important point is the organisation’s ability to turn the problem of garbage into a source of continuous income, as well as to find suitable job opportunities for many of the young people of the village. Additionally, the ability of the Foundation to mobilise the necessary monetary resources for the project in such a short amount of time, whether through donations or charitable loans, demonstrate a clear use of social networks in the village. This is an advantage not enjoyed by large companies or government agencies, as there is little trust between these parties and the local communities, as a result of the former’s inability to work with little resources and at this scale. This in turn leads to a financial burden on citizens, the result of the ballooning size of administrative organs of these entities to deal with these scales, unlike the case of small organisations working on the lowest administrative costs possible. The Nahda Foundation is proud of its ability to successfully manage such a project and obtain financial sustainability for it, making this known in its commitment to working on and implementing successful projects that serve the community. Distinguishing itself from other institutions as well, it does not consider itself a charity or philanthropic activity.

There is no doubt that the Initiative is doing its work much better than the government had been performing, in terms of efficiency, interest, commitment, proximity to the ground and capability of evolving to meet circumstances. But the governments role cannot be simply repudiated. The duty of state agencies in such a case should go beyond providing resources which civil society organisations would otherwise be unable to obtain (which was already the case in Nahia), but should also be larger and include provision of technical support and training in areas of recycling and solid waste management, so as not to stop the role of civil society institutions at merely collecting the trash.

We must also extend the role of government agencies to supporting such smaller entities to provide such services directly to citizens. Likewise the state should work to provide financial resources to these entities directly through grants and soft loans, instead of having the state collect fees from citizens and passing those on to large companies that have proved unsuccessful. This, in turn, raises the issue of the financial resources that the state collects as fees for sanitation on electricity bills, whose inefficiency and constitutionality have both been causes of controversy.

This is impossible to achieve except through reconsideration of the role of the state with respect to such entities and small enterprises, turning it to recognise that its true role is to support and formally recognise such entities. The current institutional environment does not allow for such small entities to apply for contracts and tenders in solid waste management that are issued by the different district administrations. Such tenders currently are only available to large corporations, both due to the size of the areas covered or the prohibitive amounts of insurance required to enter the bidding. In this way, the state and its citizens are deprived of the active role that civil society and small businesses can play. Initiatives such as these remain under the framework of current jurisprudence, and constrained within the limits permitted by the state on the scope of their activities and whatever charities they might receive from the government depending on the amicability of their relationship with the state.

The success of the Nahda Foundation’s garbage collection project in Nahia poses a variety of questions about the possibility of successfully reproducing it in other areas. Is it possible for the foundation to continue working in such an amicable framework, which may be subject to the whims of officials who may at any moment withdraw their support for the project? Without a doubt, the review of such a relationship and the attempt to put it into a more institutionalised framework can ensure the rights and duties of the state, such small entities, and citizens, whether in terms of efficient management of resources or the level of services provided.

Perhaps this may in fact lead to paths to replicate the success of Nahia’s experiences in other places, dealing with a problem that has thus far defied solutions.

LINKS

Nahia Tomorrow

“Sawt Nahia” Newspaper

“Abo Treika exposes Nahia’s trash problem in pictures; citizens and the sanitation department support him, the head of Kerdasa district accuses him of lying”

“Under the slogan “Our village in our sights” revolutionaries clean the trash from Nahia’s streets”

“The Nahia Solid Waste Project: Between Criticism and Evaluation”

“The ‘Tricycle’ succeeds in removing Nahia’s trash”

Statement of the Popular Front for Abating Corruption (part of the Nahia Popular Committee) regarding the Nahia Garbage Project

The Popular front for Abating Corruption (Nahia Security Committee)

Comments