Masākin `Uthmān

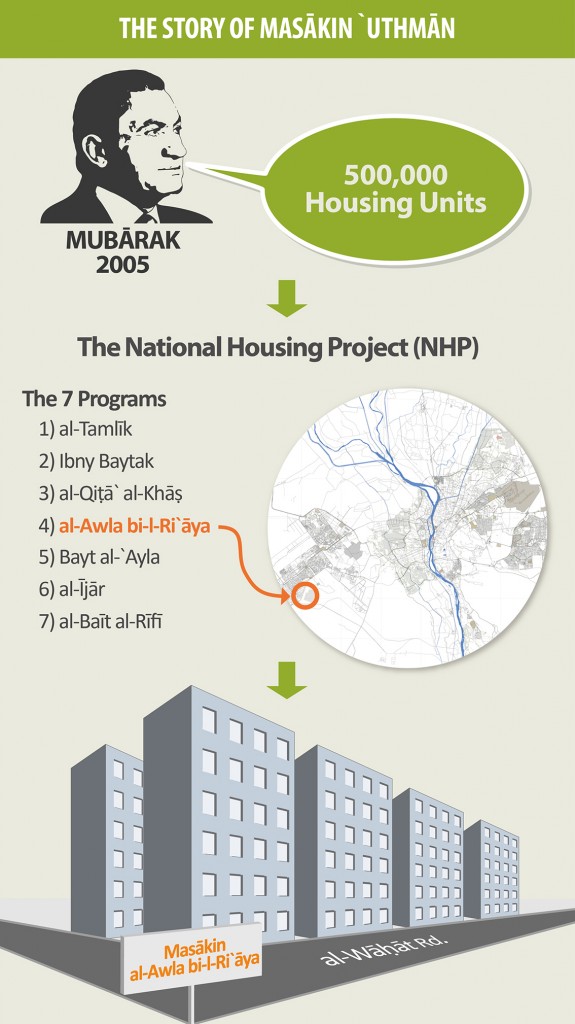

Gamāl Mubārak: Program to provide half a million housing units―Al-Ahram, 2005

Cairo slum residents to be relocated within four years―Al-Ahram,2010

‘Cairo’: We moved around 17,000 families from ‘dangerous places’ into new housing–Al-Masry Al-Youm, 2013

Maḥlab visits ‘Awla bi-l-Ri`āya’ housing in October and affirms: ‘We won’t leave whoever messes around with people’–Al-Masry Al-Youm, 2015

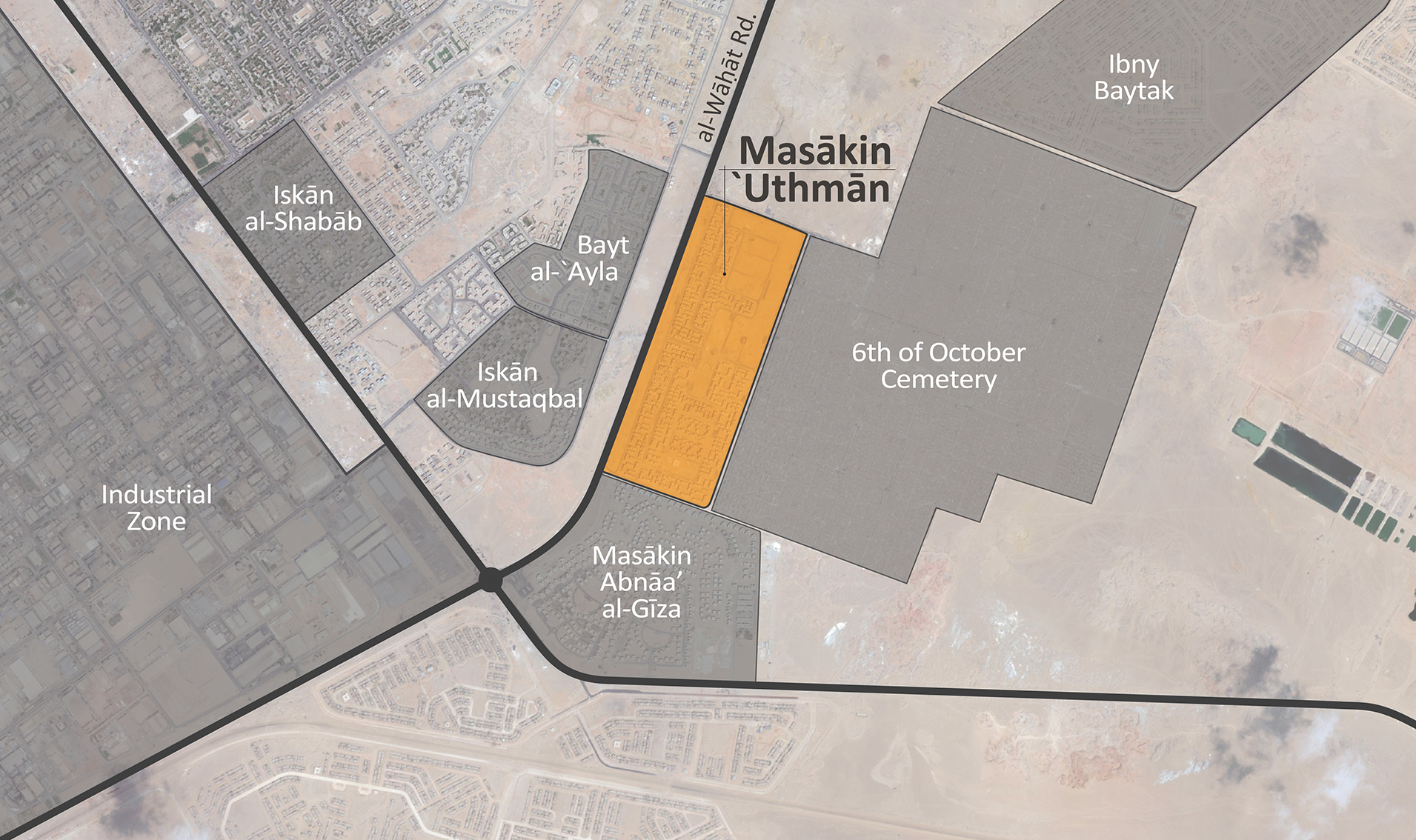

Masākin `Uthmān’s location in relation to the other areas in 6th of October such as the Industrial Zone, al-Ḥuṣary Square, and al-Shaykh Zāyid City.

Masākin `Uthmān in Numbers

Governorate: NA*

District: NA*

Area: 200 Feddan

Population: 14,0001*

Masākin `Uthmān, originally a social housing development aiming to provide housing for very low-income individuals or small families, has witnessed several changes since its development. Today, Masākin`Uthmān’s current residents live under different tenure terms and constitute quite a diverse population. Its residents, having come from different areas and countries, have almost nothing in common but their need for affordable housing and hence their current place of residence. This development can be attributed to a number of factors and events. In 2008, a rockslide occurred in al-Duwīqa, an area in Manshiyāt Nāṣir, killing 119 people. This crisis prompted authorities to action and led to the establishment of the Informal Settlements Development Facility (ISDF), now under the jurisdiction of the recently founded Ministry of Urban Renewal and Informal Settlements (MURIS). In attempts to remedy the situation, the ISDF developed a classification scheme to distinguish “unsafe” from “unplanned” areas and identify the most life-threatening areas requiring immediate intervention and the evacuation of inhabitants. Fearing another disaster, the governorate of Cairo started evicting people living in the vicinity of al-Duwīqa from their homes as well as inhabitants of other unsafe areas and resettling them in the completed “Awla bi-l-Ri`āya” units in 6th of October City.3

The Place and its People

Marking the entrance to Masākin `Uthmān is a large sign ironically reading “Mashrū` Iskān al-Muwātinīn al-Awla bi-l-Ri`āya” [Housing for the Most Care-Worthy Citizens]. Once inside the area, it becomes clear how little care the place and its people have been given and how forgotten they are. The site includes nothing but almost identical six-story blocks and a handful of shops and coffeehouses dotted around. The uniformly designed blocks – varying only in façade color – are tightly packed together in groups and separated by wide corridors and sizeable plots. These in-between spaces were intended to serve as community gathering nodes and child-friendly play areas. In reality, however, many of these spaces are flooded with sewage and household solid waste, while others are occupied by residents, who have set up makeshift tent homes and/or used to rear livestock. These spaces also attract the children in the area, who are often found loitering and playing unattended amidst the garbage heaps and stray dogs. Although Masākin`Uthmān has an open layout and is very walkable, the suboptimal use of the aforementioned spaces along with the overwhelming uniformity of the blocks, the emptiness of their surroundings, and the lack of signs and distinguishing characteristics make the place feel dull, uninviting, and a little intimidating.

The only area within Masākin `Uthmān resembling a traditional neighborhood, in terms of its features and vibrancy, is a wide and long passageway, which, unlike most parts of Masākin `Uthmān, has a name. On either side of this passageway, known as “Shāri` al-Arba`īn” [Street No.40], residents have set up various businesses in ground floor blocks or in the spaces in front of the blocks, essentially creating a commercial space and a main street. With the nearest markets all being outside Masākin `Uthmān, Shāri` al-Arba`īn is close and convenient for daily household needs.6 Along the street one finds a bakery, a grocery, a fish stall, a hairdresser’s and a couple of coffeehouses, among other shops and services. With vendors always out by their storefronts, children playing, teenagers whizzing around on motorbikes, and “mahrajānāt” music ringing in the background, “Shāri` al-Arba`īn” is without a doubt Masākin `Uthmān’s liveliest area.7

“Sūrī wa-Aftakhir wa-bi-Masākin `Uthmān Sa’ntaḥir” [Syrian and Proud, and Suicidal in Masākin `Uthmān]

Such feelings of alienation and despair, brought about in part by the physical environment and living conditions in Masākin `Uthmān, are also the result of a weak and fragmented social fabric. Most of Masākin `Uthmān’s residents had come to the area alone or knowing only a handful of people and have chosen, due to various reasons, either to remain solitary or to socialize within a small and familiar group. Refugees, in particular, being subject to verbal harassment and abuse, prefer to keep interactions with others in the area to a bare, utilitarian minimum and to interact within their own separate communities. Differing socio-cultural levels and the proliferation of crime and drugs in the area are additional factors that motivate people to keep to themselves and mind their own business. Some parents (mostly non-Egyptians) keep a close eye on their children and forbid them from playing in the street, lest they pick up bad manners from other children and naturally, out of concern for their safety. Syrians and Sudanese also tend to self-segregate by sending their children to community-founded Syrian and Sudanese schools located within Masākin `Uthmān or close by. These schools provide familiar and safe environments and deliver a sound education, especially compared to that delivered in Egyptian public schools. The glaring lack of cohesion, let alone neighborly relations, among the residents and between the different groups further makes life in Masākin `Uthmān unpleasant and unenjoyable for its residents and does not enable them to unite and work together towards finding solutions to their common problems.

What are the Problems in Masākin `Uthmān?

In their day-to-day lives, people living in Masākin `Uthmān face a myriad of problems, which can be summarized as follows:

Housing Unit Size

The standard 42m², two-bedroom apartments are much too small for many families. Families composed of more than four members and children from both genders complain of crowding and of having to put up with inappropriate and unhealthy sleeping arrangements. Furthermore, residents find their 2m² bathrooms uncomfortable and physically challenging.

Remote Location and Poor Infrastructure and Service Provision

Masākin `Uthmān’s distant and isolated location is not merely an inconvenience to its residents but a major hardship, especially since the area is devoid of basic amenities, functioning services and employment opportunities. A “basic education”8 school is now under construction and although a family health unit is in place, it is yet to be adequately equipped.9

Making matters worse is the lack of public transportation. Tuktuks (motorized rickshaws) and minibuses are the only modes of transportation available to Masākin `Uthmān’s residents. To do the most basic of things such as buying affordable food, going to work/school, or getting medical attention, people with already modest incomes have to incur substantial transportation costs. For children particularly, reaching the closest schools (located in the housing developments of Bayt al-`Ayla and Iskān al-Mustaqbal) is not only a costly endeavor but a dangerous one too, since the children have to cross the Wāḥāt al-Baḥariyya high-speed road: a highway with no pedestrian crossing provisions. This road is of major concern for Masākin `Uthmān residents as it has been the site of numerous accidents, which have tragically caused the death of children from the area.

Another problem seriously affecting the residents’ living conditions is the irregular and unreliable water supply. Although water reliability issues have impacted many around the city, Masākin `Uthmān residents have had it worse than most. On an almost daily basis, residents experience water cuts for several hours. Sometimes, the cuts last longer. People living in the area say they had no water for an entire month during the summer of 2014. The water supply issues, which had begun in June 2014, led some to block the Wāḥāt al-Baḥariyya road on June 11, 2014.10 In response, the police arrested a number of the protesters and referred them to prosecution. The 6th of October Misdemeanor Court did ultimately acquit the defendants, yet the water supply problem persists and remains unaddressed.

Limited Economic Opportunities

The entire country has been facing an economic recession over the past few years, making it more difficult for individuals living in remote areas to secure a job. To earn their livelihoods, Masākin `Uthmān’s residents generally either set up kiosks and small businesses within the area or seek employment in nearby areas as factory workers, cleaners, and mall security personnel, among other blue collar occupations. Employment-seeking women, in particular, are generally constrained to informal, home-based jobs. Yet, even with a source of income, most of Masākin `Uthmān’s residents struggle to make ends meet. While those running informal local businesses complain of the lack of business in the area, those employed complain about poor pay.

Lack of Safety

Besides all of the above-mentioned problems, people in the area generally feel threatened and are uneasy. This feeling is a result of a number of reinforcing factors. The desertedness of the area combined with the lack of a police station and the authorities’ general abandonment of the area has helped make thuggery and violence commonplace in Masākin `Uthmān. Moreover, as people do not know and do not trust each other, simple everyday interactions often flare up into disputes, which are almost always settled violently. An additional and significant cause of insecurity for the residents is their tenure status. Those living in allocated units do not feel secure in their housing as the lease contracts that the Cairo governorate has granted them are only temporary and also because they have found difficulty in making their rent payments, ever since the relocation of the payment point outside Masākin `Uthmān, following a violent clash. Also concerned are those living in illegally sublet units, who are not officially eligible for the units in the first place.

Negative Perception and Attitudes toward the Area

Although drug dealing and crime do exist in the area, as reported by interviewed residents, the blanket perception held by outsiders that all of Masākin `Uthmān’s residents are drug dealers and criminals is illogical and harms an already disadvantaged group and leads to further marginalization of the area and its people. According to interviewed residents, the area’s reputation is so poor that tuktuk drivers often refuse to take people heading there.

Why is it important to examine Masākin `Uthmān?

The importance of this problem-ridden place lies in the crucial lessons it offers. Although this housing estate was intended to be a solution to existing problems, it has become a problem in its own right. Building blocks upon blocks has not solved the housing shortage and while resettling people from unsafe areas may enable authorities to wash their hands of a potential Duwīqa-like crisis, the execution of the resettlement process and the lack of follow-up have essentially contributed to the development of a real and felt crisis. Signs of failure abound in Masākin `Uthmān:

- Construction and finishing works are still ongoing, surpassing the NHP’s six-year time frame (2005-2011).

- The completed units do not exclusively house the “Awla bi-l-Ri`āya” program’s original target beneficiaries and those whom the Cairo governorate resettled from unsafe areas.

- Residents resort to other areas for basic services.

- The housing estate, though originally designed to exude a sense of order and tidiness, now increasingly exhibits features of informal areas -the very areas whose growth the state aims to control.

- The social fabric is fragmented and volatile.

- Residents across the board consider the place uninhabitable and want to escape.

The current state of the area and its residents’ daily struggles reflect poorly on the urban planning and governance processes in place as well as the state’s ability to cope with emergencies. The unsuitability of the area is glaringly clear. At the root of this is a series of flawed plans and decisions, mainly driven by political and economic interests, as well as the authorities’ inaction in recent years.

Looking at the design and planning of the area reveals their failure to address the prevailing problems and concerns they should have solved. The architects of the NHP’s “Awla bi-l-Ri`āya” program seem to have decided that 42m² is a reasonable unit size, despite that many households include extended family members beyond the nucleus parents and children. The pursuit of this approach continued as the Cairo governorate moved people from their life-threatening habitats and resettled them in Masākin `Uthmān, assuming that housing was sufficient to make a deserted area habitable. Causing further harm was the resettlement process, which, according to the residents interviewed, was conducted in haste and with little consideration. Interviewed residents said that they were given only a couple of days’ notice to move out, selective information about where they would be resettled, and left to cover the costs of transporting their belongings themselves. Upon arrival at the site, they were shocked to find themselves, not in 6th of October City, as promised, but in the middle of nowhere, and to find the apartments smaller than those promised. This was rather distressing especially since they had seen their homes demolished to the ground and were, as of then, without a place to turn back to. They were also made to wait long hours before receiving the keys to their apartments, further adding to their distress. Even when it came to the allocation of apartments, authorities showed no regard for people and their needs. For instance, they allocated an elderly woman a unit on the sixth floor (the highest floor) rather than a ground-floor unit. Unfortunately, these relocation stories are not exclusive to Masākin `Uthman.

For the area’s now long-time residents, the situation has not improved with time. Although several years have passed since their resettlement, most planned services have not been implemented and the area is nowhere close to being an adequate alternative to their former places of residence. As the country underwent major political changes in 2011, Masākin `Uthman fell further into neglect and as the resident population of the area became more diverse, a host of new social problems emerged. Even though the ISDF had conducted an area needs assessment towards the end of 2011 and developed a number of recommendations to improve the area such as installing police and social security units in the area, the vast majority of these recommendations have not been implemented.

Opportunities for Neighborhood Development

As we saw earlier, the residents’ grievances mostly revolve around not having services in the area. Now that work is ongoing to equip the existing health unit, as per the Health Minister’s statement, and that a school is under construction, residents will hopefully witness an improvement in their day-to-day lives. Of course, nothing can be said in the meantime about the significance or magnitude of such an improvement; that will depend on the ability of the provided services to quantitatively and qualitatively fulfill the needs of the residents of Masākin `Uthmān. Nevertheless, ensuring that basic public services such as health and education are, at the very least, locally available and operational would steer Masākin `Uthmān onto a more sustainable path. The provision of public transport services is also crucial. Plans for a public transportation network do exist. The planned fourth metro line will service 6th of October, connecting it to Gīza and Cairo. Also, plans to build a monorail and extend buses to service 6th of October were announced recently (GOPP, UN-HABITAT, & UNDP, 2012). Successful and timely implementation of this network would alleviate the transportation costs incurred by residents of Masākin `Uthmān and increase their mobility and access to educational and employment opportunities. Also, as the area becomes better connected physically, residents would feel more secure.

That said the provision of various services will not magically transform Masākin `Uthmān into a problem-free neighborhood. Service provision is by all means necessary, but Masākin `Uthmān is in desperate need for a vision, not patching-up. There are fundamental questions in need of answers: Should Masākin `Uthmān be a social housing area as envisioned in the NHP’s Awla bi-l-Ri`āya program, a temporary resettlement area, or a regular residential area? Or could it be all three? What kind of regulations should be applied, if any? What is feasible given the current state of affairs? What shape should interventions take?

In answering these questions, the concerned authorities, namely, the Ministry of Housing, the Ministry of Urban Renewal and Informal Settlements (under whose jurisdiction the ISDF now falls), the Giza governorate, and the 6th of October City Authority, will have to balance the need to clamp down on the lawlessness of the area with the need to avert further deterioration of the situation. For example, a reasonable first step towards establishing control over the area might seem to be the eviction of those living in unallocated units, but this is likely to do more harm than good. Most of those living in unallocated units have the same socio-economic profile as their counterparts in allocated units and have settled in the area for lack of affordable housing options. Eviction, therefore, would plunge a vulnerable group into homelessness and push it to informal areas – the very areas whose growth the state aims to control.

Instead, decision-makers should look to set new, context-relevant criteria to determine eligibility for apartments in the area. The original criteria set out for the “Awla bi-l-Ri`āya” units are too ambiguous to be of much help in the case of Masākin `Uthmān, nor is the now defacto criterion of having been relocated by the Cairo governorate from an unsafe area. A number of people residing today in Masākin `Uthmān may not fit the established criteria, yet most are, arguably, in legitimate need of government aid. Among this number would be people living in sublet units, for example. The prevailing situation necessitates that entitlement be determined with reference to people’s economic capabilities, and where relevant, also with reference to the extent of their liability. Determining liability in the case of Masākin `Uthmān will, of course, be difficult, especially since the only piece of legislation in place with regards to social housing applies only to the Social Housing Program. The Social Housing Law, passed in May 2014, obliges beneficiaries of units under the Social Housing Program to house themselves and their nuclear families in allocated units and does not permit any other use of the allocated units, except with permission from the Social Housing Fund. The question that arises is how should the government deal with the unlawfully sublet, sold or occupied units in Masākin `Uthmān, particularly that these beneficiaries are low-income individuals in need of affordable housing?

Moreover, people whom the Cairo governorate allocated units feel that they are always at risk of losing their apartments to thugs in the area. Thus there is a need to secure the area and crack down on thuggery, but besides that the Cairo governorate needs to extend the lease period and make the necessary arrangements to allow tenants to pay their monthly rent.

To improve the situation in Masākin `Uthmān, decision-makers may also need to look towards a different decision-making process. Masākin `Uthmān illustrates how rash, top-down decisions can culminate in disasters so why make more such decisions? 11 To effectively address the issue of tenure or any other issue for that matter, decision-makers need to develop an understanding of the area and acknowledge the developments, of which the concerned authorities have been long unaware or dismissive. In efforts to do so, they should continually seek and welcome the involvement and cooperation of on-the-ground actors heavily involved in the area. Local NGOs such as Sha`rāwy Foundation for Development and issue-specific actors are an untapped resource who often invite and attempt to cooperate with entities interested in developing the area. There is a undeniable need to strengthen the social fabric in the area and create a safer and more hospitable environment for refugees, in particular. UNHCR had, in 2014, initiated a project, which demanded the cooperation of a number of actors, including the 6th of October City Authority, Sha`rāwy Foundation, and local residents to address this problem. Thanks to such a cooperation, the project – an open play area for children – has come to fruition, and in February 2015, the space named “Geneina” [Garden] was inaugurated in the presence of representatives from the 6th of October City Authority.12

It is important to keep in mind that the development of any area, and Masākin `Uthmān is no exemption, is impacted by its surrounding. The future of the area lies not only in the decisions issued for it, but also in the national vision guiding urban development. At the Egypt Economic Development Conference (EEDC) held in Sharm al-Shaykh on March 13-15, 2015, 6th of October City (where Masākin `Uthmān is located) was one of the locations spotlighted by the Egyptian government for investment. Projects proposed for the area included “October Oasis Mega Urban Development Project”, “6th of October Urban Oasis”, “Marabet Equestrian & Sport Facilities Complex”, and “6th of October Touristic City”.13 During EEDC the Ministry of Housing signed a memorandum of understanding with Palm Hills and Aabar for the “October Oasis” project and another with Arabia Group for the “6th of October Touristic City”. Plans drawn up by Archplan for the “October Oasis” include water features, lush greenery, golf courses, and Dubai-esque skyscrapers. The vision for the touristic city (to be built in the vicinity of the Great Pyramids and the Grand Egyptian Museum) is similarly grandiose; a rendering published by Arabia group features a 7-star temple-style hotel, a virtual gaming center, shopping malls, and a theme park. According to Dr. Mustafa Madbūly, the Minister of Housing, 6th of October will be the tourist capital of Greater Cairo. Assuming that these projects are realized, what will become of Masākin `Uthmān? Madbūly claims that the Ministry proposes such investment projects, mainly to finance social housing projects and water and sanitation projects and to create employment opportunities. But given the government’s track record in managing Masākin `Uthmān, it is difficult not to take such promises with a grain of salt.

The current situation in Masākin `Uthmān, which is nothing short of a disaster, could be attributed to specific public figures, governmental entities, events, or even the people themselves but it lies first and foremost with authoritarian governance structures, top-down, “high-modernist” planning, and a disregard for citizens’ right to adequate housing. Despite evident and persistent failure, high-modernist planning remains the preferred mode of planning in Egypt to this day. Contrary to its popularity and seemingly grandiose results, this type of planning usually results in disasters rather than solutions because it relies on select facts and assumptions rather than a thorough understanding of the situation and the needs of the target beneficiaries. In doing so, target beneficiaries are reduced to monolithic categories and complex and changing realities are ignored. Moreover, this type of planning usually seeks to create quick-fix solutions and/or political and economic gains and so, inevitably, resulting plans tend to be characterized by myopia (Scott, 1998).

So, can something be done about Masākin `Uthmān? Well, yes. Providing the area with services and addressing other key issues would certainly help make Masākin `Uthmān a more habitable place for its residents. But if it is to become sustainable, a people-centered, rights-based approach will be needed.

REFERENCES

GOPP, UN-HABITAT, & UNDP. (2012). Istrātījīyat al-Tanmiyya al-`Umrānīyya li-l-Qāhira al-Kubra. Al-Juz’ al-Awwal: Al-Rū’ya al-Mustaqbalīyya wa-l-Tawajuhāt al-Istrātījīyya [Urban Development Strategy for Greater Cairo. Part 1: Future Vision and Strategic Directions].

ISDF. (2011). Taqrīr Lagnat Taqdīr al-Iḥtiyajāt al-Khadamiyya li-Tawtīn Sukān al-Manātiq al-Muhadada li-l-Ḥaya bi-Madīnat Sitta Uktūbar [The Committee’s Report on the Service Needs of Residents Resettled from Unsafe Areas to 6th of October City].

Scott, James C. (1998). Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

2.Besides the Arab Contractors, there were two other contractors: the Gīza Public Company and al-Naṣr Company.

3.For a deeper understanding of the ISDF’s resettlement process and the roles of the different governmental entities involved, see TADAMUN’s “Coming Up Short: Egyptian Government Approaches to Informal Areas”.

4.Bayt al-`Ayla [The Family House] is a two-phased housing ownership program implemented only in 6th of October City. This program, designed to meet state employees’ housing needs, consists of 1-3 story buildings with larger units. For this program, the target number of units (3,000) has been met and the site includes a basic education school, a market and a mosque.

5.Iskān al-Mustaqbal [Housing of the Future] is a social housing project, which was launched in the late 1990s under the auspices of Sūzān Mubārak and implemented in a number of new cities, including 6th of October City.

6. “Mahrajānāt” [Festivals] is an underground genre of music pioneered by youth living in Cairo’s informal areas. For more on this music genre, see Deutsche Welle’s video report “Mahraganat: Cairo’s Music Revolution”.

7.In the original plan, a designated commercial zone was allocated at one end of the site, however, it is not used and it is unclear why the gihāz is not operating it. At the same time, this commercial zone is on the opposite end of the majority of inhabited blocks. .

8.The term “Basic Education” [Ta`līm Asāsy] is used in Egypt to indicate the nursery, primary and preparatory stages of education.

9.Construction of the school only started in December 2014. As for the family health unit, it has been locked and disused ever since the completion of its construction in 2012. It was only after Maḥlab’s visit to the area on March 6, 2015 that the facility was opened for limited use. In a statement made on March 7, `Ādil al-`Adawī, the Minister of Health, said that mobile clinics would provide services in the area until the facility is fully equipped and functional.

10.The documented duration of the June water outage is several days, but this is because the available news coverage is dated from early June, at which time the protest and ensuing clashes with security forces took place. The duration reported unanimously by residents interviewed in the following months is, on the contrary and naturally, several weeks.

11.In March 2015, Prime Minister Ibrāhīm Maḥlab ordered the shops lining Shāri` al-Arba`īn to be shut down and relocated, in an attempt to re-exert order. The shops were to be relocated to a plot designated to serve as a football pitch. Fortunately, Maḥlab’s decision has not been implemented. Moving commercial activities to this spot would have deprived the children and youth from a much needed (and desired) space. Moreover, the plot is directly adjacent to a school so a space for children and youth, such as a football pitch, is a more logical use of space.

12.The Geneina Project was designed and implemented by Takween Integrated Community Development – one of TADAMUN’s partners. For more on the project, please see Geneina.

13.These projects (or versions of them) were previously showcased by NUCA at the 2010 Cityscape Global conference held in Dubai. According to this article, in 2010 NUCA had presented investors with projects for a grand park, an equestrian center, and two touristic projects. In an interview held at the conference, `Ādil Najīb , then senior vice president of NUCA, mentions the “Oasis” project being one of the two touristic projects.

![Shari’ al-Arba’īn [Street No.40], Masākin‘Uthmān. ©TADAMUN](http://www.tadamun.co/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/IMG_761.jpg)

Comments