Adaptive Re-use: A Recipe for Revitalization

Have you ever seen an old building crumbling away next to an overshadowing high-rise building? Or another closed and fenced-in? If you live in Cairo, Giza or many other Egyptian cities, you are bound to have spotted not one, but several such buildings. “So what?” you may reasonably ask. Some will share your sentiment, and add: “Better demolish these good-for-nothing buildings and make use of all that space.” Others will answer, in rebuke: “How dare you say such a thing? What about our history, our heritage?”

Irreconcilable views? Not necessarily. Efficiency or profitability need not be at odds with heritage conservation. If restored and re-used, these buildings can be useful – even profitable. Proof of this exists, and can even be found in our city. Indeed, a number of buildings in the Greater Cairo Region stand today as testaments to the possibility of saving urban heritage, while creating some wider benefit. This number includes the Aḥmad Shawky Museum and the Greater Cairo Library, to mention just a few (ElKadi & Elkerdany, 2006).

The Greater Cairo Library, located in Zamalik, was originally a residential villa.

Source: Great Cairo Library

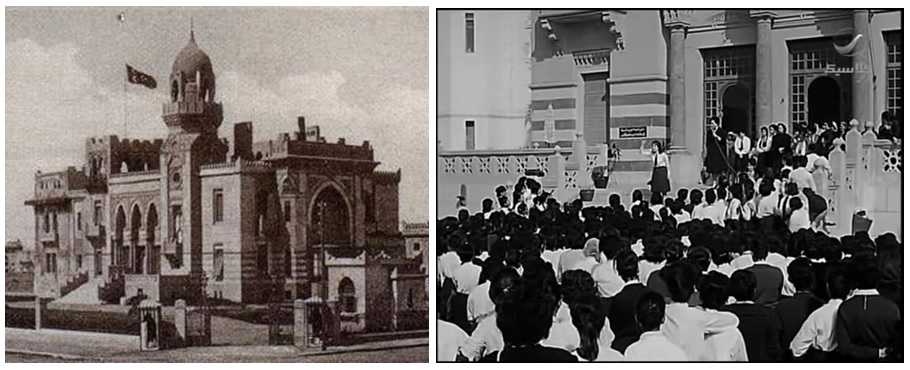

Some of the buildings that we now find in a deplorable state were at one time reused for a purpose other than its original purpose. The dark pink abandoned palace on Champollion Street in Downtown Cairo is one such building. Though it had started as a palace belonging to Muḥamad `Ali’s grandson, Sa`id Ḥalīm Pasha, it later came to house al-Naṣiriyah School for Boys.1 Another building, which had undergone a similar transformation, is al-Sultāna Malak’s Palace in Heliopolis (Raafat, 2005).2

Students of al-Naṣiriyah School pose for a school photo, May 1939. The arcuated doorways and the sculpted keystones in the background allude to its palatial origins.

Source: sakeb600 – CC BY-SA 2.0

The Palace of Sultāna Malak was transformed into a girls’ secondary school in the 1950s. The opening scenes of Henry Barakāt’s “The Open Door” (1964) feature this palace-turned-school. Notice the ablaq masonry discernable in both the photo and the still of the film.

Of course, the current state of the aforementioned palaces, as well as of other palaces-turned-schools, such as `Umar Ṭūsūn’s Palace in Shubrā, may beg the following questions: Should these places of grandeur, beautifully and intricately designed by renowned architects, have been so ruthlessly transformed into schools? Should school-age children have been let inside?

Dilapidated, disused and forgotten: a result of re-use?

From left to right: Sa`id Ḥalīm Palace, downtown Cairo; Sultāna Malak Palace, Heliopolis; `Umar Ṭūsūn Palace, Shubra.

Further, do these buildings embody a warning? Does the same fate also await buildings that have been recently re-used and opened for public or community use?

Turning an abandoned or unused building into a school or a library or a hotel kills two birds with one stone: the building’s architecture and features are preserved, and a new, useful space emerges out of the old, tired structure. In theory, the idea is quite sound. As for its success in practice, that depends on whether the use selected is appropriate for the space, and whether the building is accordingly adapted and properly maintained. When it comes to determining the type of use, there are (or should be) no absolutes. For instance, converting all threatened buildings into museums or boutique hotels is not a fool-proof approach, nor is it the most optimal – especially if the aim is to save urban heritage and create public benefit. Housing service facilities such as schools (as had happened in the cases of Sa`id Ḥalīm and Sultāna Malak palaces) could also be a fair choice. There is nothing to say decidedly that one use is always better than the other; buildings, contexts and needs differ, and so each case is better assessed individually.

Applying the idea with sensitivity to the context and the needs at hand can deliver multiple, cross-cutting benefits. One project that did this, and succeeded to a considerable degree, was the Aga Khan project launched in the impoverished Cairene neighborhood of al-Darb al-Aḥmar. This article will discuss the Aga Khan project and how it adapted historic buildings in this low-income area to be a vital part of the community.

The Aga Khan Project

In the late 1990s, the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC), an agency of the Aga Khan Development Network, turned its attention to al-Darb al-Aḥmar: a deteriorated neighborhood rich with character and history. By then, the Trust had already begun working at the hilly site overlooking the neighborhood, with the aim of giving Cairo a “Green Lung”: al-Azhar Park.3 Meanwhile, in al-Darb al-Aḥmar, it hoped to address both physical and socio-economic needs, in part by restoring architecturally- and historically-significant buildings and re-using them. Among the targeted buildings was a former school in Aybak Alley as well as a house dating from Ottoman times in Bāb al-Wazīr Street (hereafter referred to as “Darb Shughlān School” and the “Ottoman House” respectively).

As al-Azhar Park was taking shape, the AKTC adopted re-use of deteriorating buildings to help revitalize the neighboring area of al-Darb al-Aḥmar. The AKTC’s work at No.7 Zuqāq Aybak and No.27 Bāb al- Wazīr illustrates the potential of adaptive re-use.

AKCS-E, or, Aga Khan Cultural Services-Egypt, is the local affiliate through which the AKTC carried out these and other interventions in the area. Later on, in 2005, al-Darb al- al-Aḥmar Community Development Company (CDC) was founded to manage the project and its various programs.

Situation before the Project

Naturally, both Darb Shughlān School and the Ottoman House were, after decades of neglect, in a dire state. Both buildings were full of heaps of dust and debris and were missing several of their original features, most notably wooden features, which had been gradually dismantled over the years. The buildings’ exterior structures were, however, more or less intact and the design discernible. The remaining interior features, though not intact, were sufficient to deduce materials and techniques used at the time of construction. The condition in which Darb Shughlān School and the Ottoman House were found was reflective of al-Darb al-Aḥmar’s deteriorating urban fabric. Not only did valuable buildings stand abandoned and disused but as revealed by a 2003 baseline survey, the area as a whole fared poorly. Most respondents considered their housing to be in poor condition and hazardous, and with income levels significantly lower than the national average, most did not enjoy comfortable standards of living. Also of concern at the time were the levels of garbage in the area, the poor infrastructure networks, and the lack of activities for children (Shehayeb, 2004).

History of the Buildings

Darb Shughlān School, a prominent, four-story building, directly adjacent to the Ayyūbid wall, was originally constructed in 1911 for residential purposes (O’Kane, 2009). In the 1940s, it became home to “Fātma al-Nabawiyya Girls’ Primary School”, but around 40 years later, the building showed signs of deterioration and so the school relocated (AKTC, n.d.). In spite of this, the building continued to be referred to as “Darb Shughlān School”, with “Darb Shughlān” signifying the particular area in which it falls.4 In the period between the school’s relocation in 1988 and the Aga Khan intervention in the early 2000s, the building had suffered much damage and was, by residents’ accounts, even used as a garbage dump.

Relatively less information is available on the Ottoman House, nestled between the Āqsunqur Mosque and the Khāyrbak Mosque-Mausoleum in Bāb al-Wazīr. What we do know is that it dates to the 17th century and that it was constructed by Ibrāhīm Āghā Mustaḥfiẓān, a commander of the Janissary Citadel Guards, who seems to have taken a particular interest in al-Darb al-Aḥmar and its monuments. In 1652, Mustaḥfiẓān embarked on the restoration of the 14th century Mosque of Āqsunqur. He strengthened its structure and redecorated it using blue Iznik tiles, characteristic of Ottoman mosques, hence its other name “The Blue Mosque” (Behrens-Abouseif, 1989). Besides restoring this mosque, he had also carried out several constructions in the area. His constructions included a “sabil” – a public water fountain – and a “rab’” – a Mamluk/Ottoman era building type which usually served residential as well as commercial purposes (Warner, 2005; Williams, 2008).

The Idea

The fundamental goal driving the project was the revitalization of al-Darb al-Aḥmar. The project had identified two areas of concern: the buildings and the community. Both were, essentially, neglected and in decline yet bursting with potential. Aiming both to rescue valuable buildings in the area and to meet the community’s needs and desires, the project adopted the strategy of adaptive re-use. The basic and central idea was to restore threatened buildings to the highest quality and put them back into use, wherever possible. More specific ideas as to what functions the restored buildings would serve only fully materialized and developed during the restoration processes, with the discovery of possibilities and constraints.

Central also to the conception of the project was the engagement and involvement of the community. To reinvigorate al-Darb al-Aḥmar’s withered community and ensure the project’s success and sustainability, the project made an effort from the outset to inform the residents of al-Darb al-Aḥmar about the neighboring development at al-Darāsa (the site of al-Azhar Park) to consult them about their needs, and to involve them, through vocational training, in the project’s work.

The choice of buildings to be restored was driven by the buildings’ value (inherent and potential) and location. The choice fell on Darb Shughlān School because it was considered to be a markedly unique building, incorporating features from different eras and styles. Location and size were another two factors that influenced its selection. The building was visible from the then-incomplete Azhar Park and would there have the capacity to be the revitalized face of al-Darb al-Aḥmar to the Park visitors. Further, given its size, it would have the capacity to hold many people. The project decided to restore the Ottoman House in Bāb al-Wazīr as well, primarily because of its location. The House is almost adjacent to the 16th century Mamluk Mosque of Khāyrbak, which the AKTC hoped -through its conservation efforts- to put on the tourist map. The Ottoman House’s location on a main street also meant that it would be visible to passersby and easily accessible. Finally, both buildings, though seriously deteriorated, were not beyond repair, which made them ideal choices for the project.

Project Implementation

Preparatory groundwork and research began in the late 1990s, and it was only years later, when the first steps towards getting hold of the selected buildings were taken, that things really started to take shape. This initial step proved to be quite a hurdle in the case of Darb Shughlān School. It took protracted negotiations with the building’s multiple owners to acquire the building and commence the required work.5 In comparison, it was relatively easier and less time-consuming to kick-start the process in Bāb al-Wazīr because the Ottoman House was already at the time a registered historic monument under the auspices and ownership of the Supreme Council of Antiquities (now the Ministry of Antiquities), with whom AKCS-E had partnered for the monument conservation projects.6

Having purchased the Darb Shughlān School building and obtained permission to restore the Ottoman House, the teams started documenting the buildings’ features and surveying their physical conditions. The teams managed to trace the history of the buildings and derive a good understanding of what they would have looked like in their original condition through detailed documentation, historic photographs, and where necessary, inferences from similar buildings in the area. The teams took great care to document the remaining features so that they could save as much as possible and keep the buildings’ original character intact. They also gave due attention to the buildings’ surroundings to ensure visual and cultural coherence.

At both sites, the project teams adhered to the original design and tried to use traditional/compatible materials and techniques, as much as possible. The Ottoman House had no foundation and so the team had to dismantle the remaining walls and rebuild them. To save as much as they could of the original building material, while dismantling the walls, they numbered the stones so that they could place them back again in the rebuilding process. After building the foundation, the team proceeded to rebuild the ground floor using the original stones. The two upper floors were completely missing at the time of the intervention and so the team had to complete the reconstruction of the building using red brick. Unlike the Ottoman house, the condition of Darb Shughlān School did not call for a major reconstruction of the building; most of the work revolved around repairing the damaged masonry and plaster. The missing/damaged wooden features and particularly the mashrabiyyas were integral to the design and character of the buildings and so a directed effort was made to recreate/repair these particular features.7 Moreover, when it came to the finishing touches, the teams chose color palettes in line with the identity of the buildings and their surroundings. All throughout, from start to finish, the respective teams made sure not to compromise the quality, character, and authenticity of the buildings.

A member of the restoration team works on some decorative molding at Darb Shughlān School.

Source: AKTC

A sign designating the headmistress’ office was left in its place as a testament to the building’s history. Source: TADAMUN

Perhaps the greatest obstacle that faced both teams at Darb Shughlān School and the Ottoman House was finding a skilled technical workforce with a like-minded sensitivity to heritage buildings. The project decided to overcome this obstacle by creating the necessary skill-set through holding training workshops for local craftsmen to teach them wood restoration and conservation techniques. With expert-delivered and on-site training, the craftsmen became a most valuable resource and so their involvement did not stop at the structural and exterior restoration of the buildings. The project tapped into their skills and had them make the furniture for the restored buildings as well.

When it came to the installation of modern amenities, such as air conditioners, the respective team leaders discussed with the technicians ways to accomplish this step without compromising the character and aesthetics of the buildings. A main factor aiding the overall success of this project was the availability of funds (discussed below), which allowed the teams to give the highest priority to ensuring that the materials used were the most fitting and of the best quality.

After the completion of the restoration work at Darb Shughlān School and the Ottoman House (in 2004-2005 and 2007, respectively) a decision had to be made in regards to the future uses of the buildings. As mentioned earlier, the project aimed to utilize the restored spaces for community purposes. It was loosely intended that Darb Shughlān School would become a visitors and community center and that the Ottoman House would house community services offices. However, more pragmatic concerns had arisen, which led to a slight change in plans. The number of project staff had increased and so there was a need for greater office space that would be located close to or within al-Darb al-Aḥmar. Thus, it was decided that the upper floors of the Darb Shughlān School would house CDC: the entity that had, by then, been established to manage the project and its components. The ground floor and backyard, however, were reserved for community use. As such, the ground floor came to house a library and a computer center for children, whereas, the backyard proved suitable to host a range of activities and events from children’s film screenings and puppet shows to talks and trainings for local CSO staff. The Ottoman House, on the other hand, was transformed into a family health center.

Resources and Funding

Cost, although usually an issue in such restoration projects, did not constitute an obstacle in this project. The restoration work on Darb Shughlān School and the Ottoman house was funded by several donors. The Ford Foundation, Sandstorm, Mercedes Benz, and the Egyptian Swiss Development Fund helped cover the costs involved at Darb Shughlān School, whereas, the World Monuments Fund and the American Research Center in Egypt funded the work at the Ottoman house (Philip, n.d.). Needless to say, the availability of several interested donors and sufficient funds was instrumental to the successful completion of the restoration work, especially since actual costs exceeded the set budget. Other crucial resources available to the project included the expertise of the staff involved and the cooperation with the Historic Preservation Program of the University of Pennsylvania’s Graduate School of Fine Arts, without which the restoration of the buildings would not have been completed at the best quality possible.

Results and Impact

The restoration work at both Darb Shughlān School and the Ottoman House created immediate job opportunities and improved long-term income generation prospects. Local wood craftsmen were recruited for the woodwork, but workers had to be brought from outside al-Darb al-Aḥmar for construction and stone work, since this skill set was not found in the area. Having obtained theoretical instruction as well as practical on-site experience, local craftsmen involved had, by the end of the work, become a valuable workforce. With rare and refined skills in hand, they started to receive woodwork commissions from various entities, such as al-Azhar Park and the Cairo Governorate, for whom they completed the Lakeside Restaurant and Sūr al-Azbakiyya, respectively.

As for the buildings, they regained their former glory and became ready for use. Alongside the restorative architectural work, there were a number of programs designed to address the different socio-economic issues in al-Darb al-Aḥmar. With Darb Shughlān School and the Ottoman House finally restored, the then on-going AKCS-E programs had well-suited venues to conduct their various activities and deliver much-needed services in the area.

The buildings post-restoration. Source: AKTC & Archnet

In 2005 the community center housed in Darb Shughlān School was open and fully operational. This space played a pivotal role in revitalizing the community. Its various facilities and events attracted community members from all age groups, creating a convenient space for the entire family. Whenever there would be talks for women in the area, they would attend, bringing along their children to use the library or the computer center. They would not have to worry about choosing between not attending and leaving the children alone at home. Through the various and specialized activities, the space provided a vibrant forum for everyone to learn, develop one’s self, and have an enjoyable time with fellow members of the community.

Interviewed members of the community who regularly attended either talks or trainings at the center remarked that these were always clear and well-delivered and often made an impact on attendees. The manager of a local NGO-run nursery (also a former student at the Darb Shughlān school), who had participated in training sessions on strategic planning and good governance, among other topics, appreciates having taken part in these sessions as they enabled her to develop her knowledge and skills and to network with other NGOs in the area. Besides benefiting the adults and professionals in the community, the center provided a child-friendly space in an area otherwise lacking such spaces and offered an outlet for the children’s energy and talent. Apart from the facilities available, the center, under the wider education program, offered occasional classes in arts and music. In 2011, a full-fledged arts and music curriculum was in place, thanks to a co-operation between al-Mawrid al-Thaqāfī [The Cultural Resource] and AKTC, the fruit of which was al-Darb al-Aḥmar Arts School (DAAS). In 2009, four years into the operation of the community center, only 12% of residents interviewed for a survey thought there was a gap in children’s activities. This was a significant improvement from the results of a survey taken in 2003, where 61% of residents interviewed agreed with that statement (Shehayeb, 2009).

The restored school building provided local residents, particularly the children, with some much-needed space.

Clockwise from top left: The library, a movie screening, and a music class.

Sources: AKTC and al-Mawrid al-Thaqāfī

The health center, housed in the Ottoman House and run by the health program, offered medical checkups at affordable prices and held talks on various health-related matters. These particularly resounded with community members. As one woman relayed, after attending a talk on female genital mutilation at the center, she made an informed decision not to have her younger daughter circumcised.

Sustainability

The impressive impacts recounted above were captured shortly after the restoration was completed. 2012 saw the end of the AKTC project in al-Darb al-Aḥmar, and today, only one of the two buildings examined in this article is open and in use: the Ottoman House. The House no longer houses a clinic though; instead, it now serves as the DAAS training grounds.8 Yet, up until recently, like Darb Shughlān School, it was also lifeless. This is because in November 2014, al-Mawrid al-Thaqāfī (the entity behind the DAAS) had announced a halt of all its activities in light of state restrictions on NGOs operation, resulting in the closure of the building. Fortunately, however, with the resumption of classes in April 2015, it regained life once more.9

The current situation is less than ideal and represents a real set back, especially considering the positive impact the adaptively re-used buildings had had on the community. Sustainability was key in the philosophy guiding the overall AKTC project in al-Darb al-Aḥmar and measures were taken during the duration of the project to help ensure the continued success of the project and its various programs. From the very start, the AKTC, through its local affiliate, AKCS-E, sought the involvement of the residents of al-Darb al-Aḥmar for the very purpose of cultivating a sense of ownership and thereby assuring the project’s sustainability. The community members were not treated as spectators or passive beneficiaries, but were given an opportunity to actively partake in the project, as employees and participants. Local Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) were also brought on board, with the aim of building their capacities so that they may play a more efficient role and better serve the surrounding community. Moreover, in efforts to ensure sustainability, CDC was founded as early as 2005 so that it may take on managerial responsibilities.

These aforementioned measures had been taken to ensure the sustainability of the project, in general. If we turn to the particular re-use projects discussed, we find that the AKTC had also gone to efforts to ensure that these buildings do not fall into disuse, and quite possibly, neglect, as is now the case for Darb Shughlān School.

The wall in the backyard on which films were once projected for the children is now splattered with paint

Source: TADAMUN

The functions, which each of the two buildings came to fulfill following the restorative work, were derived from the needs raised through the surveys and assessments conducted. In other words, they were not irrelevant. Moreover, in the case of the Ottoman House, the AKCS-E had signed an agreement with the Supreme Council of Antiquities (now the Ministry of Antiquities), mandating the re-use of the building for a ten-year period, starting in 2004 (Philip, n.d.). Lastly, the buildings’ interiors were not designed so as to serve only one set function; they allow for function change, should local needs evolve.

So, the question arises: What went wrong? Residents (and former beneficiaries) trace the current situation to the January 25 Revolution. According to them, the Revolution threw everything into disarray. In the year following the start of the Revolution, the AKTC handed over the project in al-Darb al-Aḥmar to Maẓalla Association for Social Development – a NGO it had itself established prior to the handover. Maẓalla has failed since to continue the AKTC’s work to the same standard and scope, or to play a significant role in the area. “It is as though we were shown a cake but not allowed a taste,” remarked one resident, expressing his disappointment at the abrupt end of the project and its unsustainability. Thus far, since the handover, the NGO’s contribution to the area has been limited to a few, small-scale training projects. The management of Maẓalla claims that the reasons for this are the unavailability of funding opportunities and the limited number of staff.

Whatever the reasons, the lack of sustainability is evident. While unexpected events and a poor handover may well be to blame for the current situation, one may also question whether the AKTC had done enough to sufficiently mobilize the community, or whether, in any case, the project was doomed to this end, given long-prevailing attitudes to urban heritage.

Replication and Future Plans

In terms of future plans for the restored buildings in al-Darb al-Aḥmar, none explicitly exist in the case of Darb Shughlān School, which may explain, in part, why it is now closed. In the project’s final evaluation report (2012), no mention is made either of the School or of the House. The report’s recommendations are all to do with what should be done in the different areas of intervention (e.g. employment, health, and education) and the strategies to be adopted. According to Maẓalla, the school will remain closed until they find an interested tenant or a fund sufficient to relaunch a program or a set of activities for the community. There has been talks of turning the building to a boutique hotel as its size, design, and prime location allow for such use. Plus, the hotel’s revenues could help fund community needs-oriented programs. In fact, when the building was still being restored, the team had considered this idea and had made the necessary arrangements so as to allow for flexibility, should the need arise to change the building’s function.

In the case of the Ottoman House, though it is currently in use, the ten-year re-use agreement signed in 2004 is now over, and, additionally, the political climate may once again bring about the closure of the DAAS, to the detriment of the students as well as of the building.

TADAMUN’s Vision

With frequent heritage losses occurring, adaptive re-use is a much-needed solution, with potential to counter both the popular trend of demolishing buildings, and also the long-favored policy of keeping historical buildings under lock and key.10 With its myriad of possibilities, it can challenge the ideas that fuel these harmful practices. Razing buildings to the ground and building anew is easy, lower in cost, and financially lucrative, but it is not the only way to make money. Money could also be made by restoring buildings and converting them into businesses such as hotels or restaurants, or provide a public service for the community. This would also have the added benefit of keeping the urban fabric intact. Moreover, contrary to long-standing ideas, putting a building of value into use does not necessarily doom it, provided that the use is appropriate and that the building is adequately maintained.

Fortunately, in recent times, the concept of re-use has gained prominence in official discourse and even at the policy level. Currently, the Ministry of Antiquities has underway a number of restoration projects and plans to put restored buildings to various uses. In early July 2015, it inaugurated a completed project in a Mamluk complex situated in Cairo’s Islamic necropolis, popularly known as “City of the Dead”. This project involved restoring the Ḥawd of Qaytbay and adapting it to serve as a showroom for products made by local craftsmen. This particular project signals a change in the Ministry’s approach towards built heritage, at large, and in how it applies the concept. Previously, when matters of urban heritage had first attracted official attention, most buildings that underwent restoration and adaptation, ended up serving a cultural purpose. Cultural spaces are important and should be made available in different communities; and perhaps this was the most optimal use for the then-restored buildings. Nevertheless, at the same time, this revealed a narrow interpretation of the adaptive re-use concept and a failure to recognize its capacity to utilize these buildings for the community’s other pressing needs.

In a context, where there are, besides buildings in need of repair, people in need of services and jobs, adaptive re-use can be utilized not only as a heritage rescue strategy but also as a tool to ensure the provision of service infrastructure or to support employment, as the Aga Khan project did in al-Darb al-Aḥmar.

Notwithstanding sustainability issues, restoring and re-using the Darb Shughlān School and the Ottoman House – with its sensitivity to the context and needs at hand – did deliver multiple benefits. It spurred revitalization on several levels: physical, economic, and socio-cultural. Although the Darb Shughlān School has fallen into disuse, the building is in good shape and is ready to be reused. It can play the role it had played following the completion of the restoration work and be of benefit to the surrounding community once again.

Works Cited

AKTC. (n.d.). Reintegrating Historic Buildings into the Life of the Neighbourhood: The Adaptive Re-Use of the Former Darb Shoughlan School.

Behrens-Abouseif, Doris. (1989). Architecture of the Bahri Mamluks. In Islamic Architecture in Cairo: An Introduction, 94-132. Leiden; New York: E.J. Brill.

ElKadi, Galila & Elkerdany, Dalila. (2006). Belle-époque Cairo: The Politics of Refurbishing the Downtown Business District. In Diane Singerman & Paul Amar (Eds.) Cairo Cosmopolitan, pp.345-371. Cairo, Egypt: The American University in Cairo Press.

Khalil, Mufid, Mansur, Albair, & Kamil, Rushdy. (2012). Final Evaluation Report for al-Darb al-Aḥmar Development Project. Social Fund for Development.

Jodidio, Philip (ed). (n.d.). The Aga Khan Historic Cities Programme. Strategies for Urban Regeneration.Prestel.

O’Kane, Bernard (ed). (2009). Creswell Photographs Re-examined: New Perspectives on Islamic Architecture Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.

Raafat, Samir W. (2005). Cairo, the glory years: Who built what, why, and for whom…. Alexandria:Harpocrates Publishing.

Shehayeb, Dina. (2004). Baseline Survey 2003. Aga Khan Cultural Services-Egypt.

Shehayeb, Dina. (2009). Post-Implementation Survey 2009. Al-Darb al-Aḥmar Community Development Company.

Warner, Nicholas. (2005). The Monuments of Historic Cairo: A Map and Descriptive Catalogue. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.

Williams, Caroline. (2008). Islamic Monuments in Cairo: The Practical Guide. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.

Useful Links

Cairobserver. (2012). Buildings are not disposable. June 8.

Shalaby, Nora. (2013). The continuing catastrophe in al-Darb al-Aḥmar. January 15.

1.Sa`id Ḥalīm Pasha (1865-1921) held the post of Ottoman Grand Vizier between 1913 and 1917. During the First World War (1914-1918), the Ottoman Empire had sided with Germany and as a consequence, the British forces stationed in Cairo confiscated all of Ḥalīm’s assets, including the palace.

2.Sultāna Malak Turhān (1869-1956) was the wife of Husayn Kāmil (1853-1917), Sultān of Egypt between 1914 and 1917. The palace carrying her name was a gift from Baron Empain (Belgian entrepreneur and founder of Heliopolis) to her husband. After the Sultāna’s death, the palace became a girls’ secondary school. The palace building is now no longer in use but occupying the grounds today is Miṣr al-Gadīda Experimental Language School.

3.The Trust’s work in al-Azhar Park and al-Darb al-Ahmar was part of its larger, multi-country “Historic Cities Programme”, launched in 1992.

4.“Darb Shughlān” is the name of the shiyākha or the local administrative unit in which the building is located.

5.According to those who worked on the restoration of Darb Shughlān School, the building was owned by forty individuals.

6.Registration occupies a central place in the management of built heritage in Egypt. It is overseen and carried out by two governmental entities: the Ministry of Antiquities (formerly, the Supreme Council of Antiquities) and the National Organization for Urban Harmony (which falls under the Ministry of Culture). The former is responsible for monuments from Pharaonic times through to the Ottoman era, and the latter, for heritage buildings dating from the 19th and 20th centuries. The Ottoman House is on the Antiquities’ list as No.619. Darb Shughlān School, on the other hand, was not registered at the time of the project because the National Organization for Urban Harmony had not been founded yet. (To this day, it still has not made it to the list.)

7.Mashrabiyyas are ornate wooden oriel windows or balconies, designed to aerate a residence while also give its inhabitants privacy. They are distinctive architectural features of Arab-Islamic buildings.

8.At some point towards the end of the project, the health services offered at the Ottoman House were relocated to Building No. 69 Darb Shughlān (the Aga Khan Foundation’s Country Office in Egypt) but these ultimately ceased altogether.

9.For more on the DAAS, watch this episode of “Jam` Mu’nas Sālim” in which Rīm Māgid interviews the female students of the school.

10.A number of buildings under the auspices of the Supreme Council of Antiquities (now the Ministry of Antiquities) have been long closed to the public, under the pretext of restoration, or for fear of damage.

Comments