Nāhyā

“Do you know Nāhyā?”

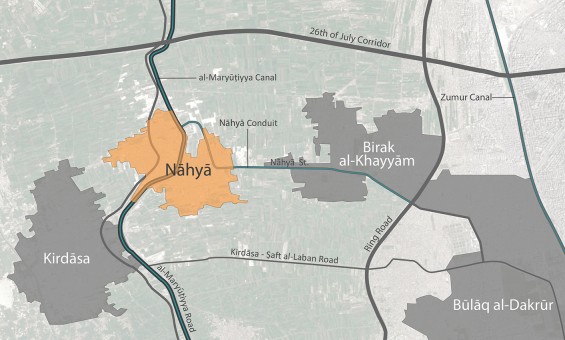

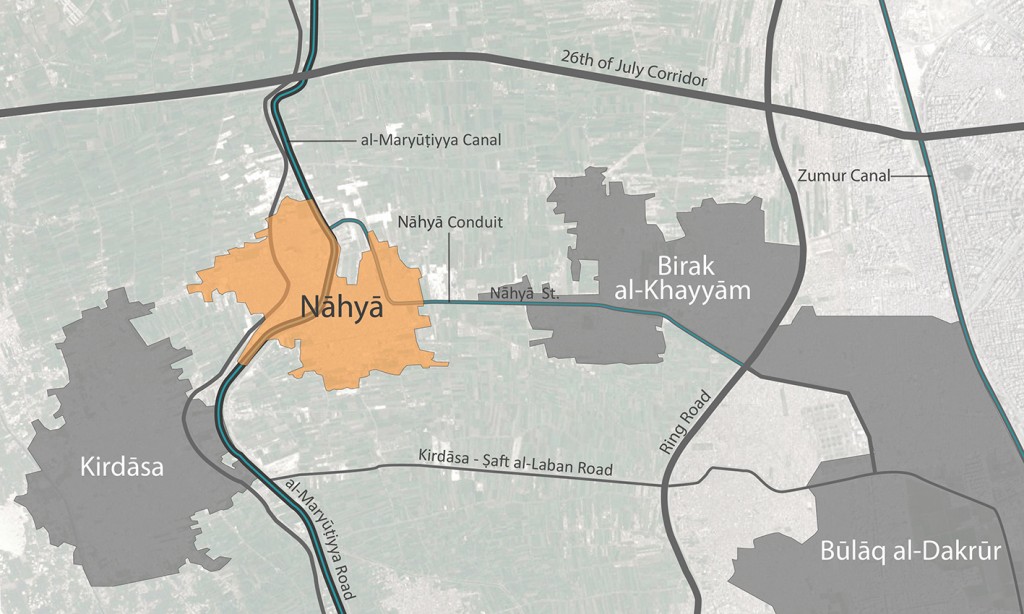

If you ask a Cairo or Gīza resident about Nāhyā it is more likely that he knows Nāhyā Street, or perhaps Nāhyā Bridge in Būlāq al-Dakrūr in the Governorate of Gīza, but not the village. Very few would know that the name of the street – which passes through Būlāq al-Dakrūr– is actually derived from this village which is situated in the Kirdāsa Region, and that the street was given this name simply because it leads to the village.

The street is not the only landmark in Greater Cairo which owes its name to the village of Nāhyā. The Zumur Canal which bisects Arḍ al-Liwā’ and the Muhandisīn District was named after the family which owned large tracts of land in Nāhyā overlooking this canal.

The village of Nāhyā is situated along the western perimeter of Greater Cairo. Unsurprisingly, it can be reached via Nāhyā Street which starts at Sudan Street in the Muhandisīn District, passing through Būlāq al-Dakrūr. To get to Nāhyā from central Cairo would require two or three bus changes. All the bus services share the same feature as they are all “privately” run since the village is not served by public transport. The buses transport passengers from the Is`āf bus-stop in central Cairo to Būlāq al-Dakrūr and from there the best means of transport to Nāhyā is the microbus or the “tuk-tuk” (motorized rickshaw). The latter is the only means of transport available within the village itself. When using private passenger vehicles, the best way is to go via the ring road up to the Kirdāsa exit and to continue from there in the direction of Kirdāsa then cross the Zumur Canal and from there turn right into Nāhyā.

Nāhyā In Numbers

Governorate: Gīza

Region: Kirdāsa

Area: 1.9 sq. km (according to aerial photographs)

Population: 44,000 (according to the Central Agency for Public Mobilisation and Statistics 2006)

The Story of Nāhyā

Historical sources refer to an old Egyptian village called “Nihit” which was devoted to the worship of the Goddess Hathor. It is mentioned in the historical book “The Dictionary of Countries” under the name of “Nahyā”. The Tawfīqiyya Plans refer to it as “Nahya”. As for the history of the village, it appears that Nāhyā was always the property of the ruler of Egypt, particularly during the period following the Arabian conquest of Egypt and until the rule of the Fatimid Dynasty. Nāhyā, Saft al-Laban and Kafr Ṭuhurmus were all agricultural lands that belonged to Khumārawayh ibn Aḥmad ibn Ṭūlūn (896 AD/ 282 H) which were used to grow fodder for the Prince’s cattle herds. The three neighbouring villages – including ‘Awsīm – were part of the land belonging to Badr al-Dīn al-Gamāli (1094 – 1015 AD) one of the Fatimid ministers. Ibn Duqmāq states in his book “al-Intiṣār li-Wāsiṭat ‘Aqd al-Amṣār” that Nāhyā was one of the holdings of the Sultanate. This continued to be the case until Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn al-Ayyūbi took over the rule of Egypt at which time its revenues were used to fund the Egyptian fleet.

We can deduce therefore that the land of the village was highly fertile which in the past imparted it with a lovely bucolic beauty. History books describe a monastery in Nāhyā – not yet located – as “one of the best and most productive monasteries” which was transformed into beautiful meadows once the Nile floods had subsided. It was a beauty spot visited by the Fatimid Caliphs such as al-Mu`izz li-Dīn Allah and al-Ḥākim bi-Amr Allah where they used to reside for a number of months each year (al-Maqrīzī).

Nāhyā’s history is not limited to the transfer of its ownership from one ruler to another. It has been the birthplace of a number of influential public figures such as Shaykh Muḥamad al-Mahdi who was believed to have been virtually the first Egyptian Prime Minister of modern Egypt by Louis Awad. According to the book “Nāhyā in History and in the Centre of Events” by Aḥmad `Abdul Latīf al-Zumur (a Nāhyā resident) the Shaykh became prominent during the struggle between the Egyptians and the Ottoman ruler, Khurshid Pasha. Community leaders at the time selected Muḥamad `Ali to replace the Sultan-appointed ruler. In a popular gathering held on 13 May 1805 which was led by scholars and elders, it was announced that Khurshid Pasha would be deposed and replaced by Muḥamad `Ali. The minutes of this meeting were written by Shaykh Mahdi himself and stated that: “In line with traditions and the dictates of Islamic Shari`a law, people have the right to appoint their rulers and have the right to depose them if they deviated from just rule and became prejudiced because unfair rulers operate outside Shari`a law.” (The History of the National Movement – Part Two by al-Rāfi`ī). When researching parliamentary life in the modern era, Louis Awad stated that this declaration laid the foundation for the development of constitutional jurisprudence in modern Egypt and conclusively established the state’s supremacy as the source of power.

However, in direct opposition to the principles laid down by Shaykh al-Mahdi, Muḥamad `Ali adopted an intransigent dictatorial style of rule and removed popular leaders who endangered his exclusive rule of Egypt. Among these popular leaders was Shaykh al-Mahdi himself who was turned down for an appointment at al-Azhar by Muḥamad `Ali. Among Muḥamad `Ali’s measures to strengthen his hold over the country was a step directly related to the story of Nāhyā. He seized all Egyptian land except for land whose owners were able to prove their legal ownership, which was the case in Nāhyā. Shaykh Aḥmad al-Zumur owned two thousand feddans which he had been awarded 30 years before as a reward from Muḥamad Bayk Abū al-Dahab in return for his support during the coup against his master `Ali Bayk al-Kabīr (who in turn had led an unsuccessful coup against the Ottoman Sultan to gain sole rule of Egypt). Consequently Nāhyā remained outside Muḥamad `Ali’s ownership which explains the origin of the name given to al-Zumur Canal. This also demonstrates the historical and well-established origins of al-Zumur family among whose members there are some prominent and some infamous members, such as General Aḥmad `Abūd al-Zumur who was one of the heroes of the October War. Among them also is `Abūd al-Zumur who was one of the conspirators in the assassination of ex-president Muḥamad Anwar al-Sādāt as well as the television presenter Farīda Al-Zumur . Moreover, among other prominent figures to emerge from Nāhyā is `Iṣām al-`Iryān who is one of the leaders of the Muslim Brotherhood and Muḥamad Abū Tarīka the popular ex-footballer in al-Ahlī club.

The Place and its People

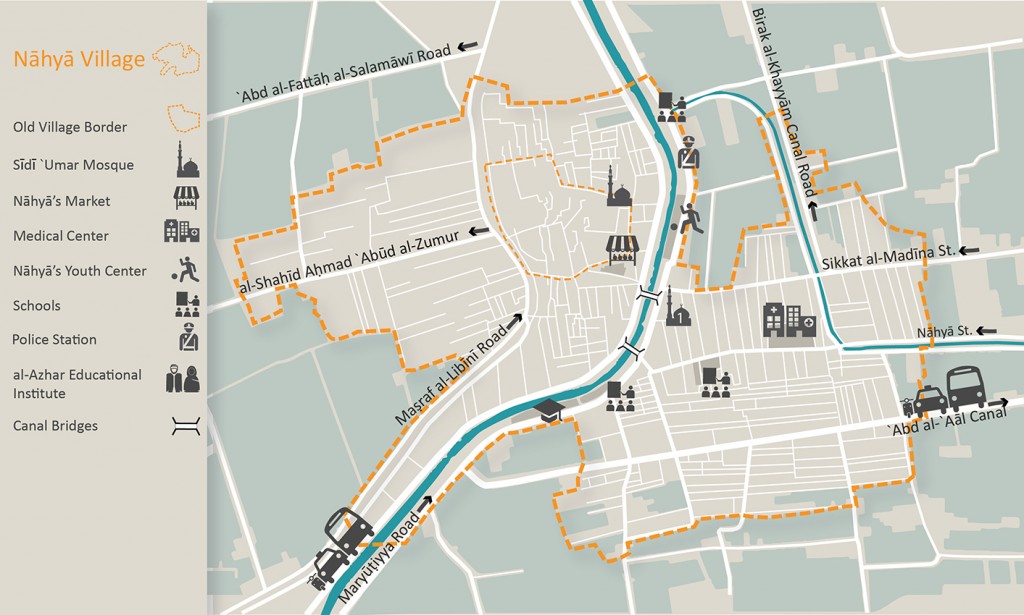

Like all Egyptian villages, the town planning in Nāhyā, until the last century, consisted of an enclosed, central urban structure featuring narrow, winding alleys and closely situated buildings. Surrounding these blocks is a circular road called “Dāyir al-Nāḥya” which separates the village from the surrounding agricultural land. With time, the village rapidly extended in all directions at the expense of the surrounding agricultural land with the new developments spreading in long narrow strips along the borders of the agricultural lands it had replaced.

Not much of the rural appearance of the old buildings remains, as these were gradually pulled down and replaced with more modern reinforced concrete structures. Some of the old buildings remain but these are now few and far between amidst the more modern developments in the village which is now dominated by medium-rise buildings of around four storeys high. In general, the older buildings appear to be on the way out as their fabric continues to deteriorate due to lack of maintenance, in contrast to the structural stability which characterises the more modern buildings. This is not only the case with the older buildings in the village but also for one of its most important landmarks – the mosque of Sīdī `Umar al-`Irāqī – which was built in the 19th century. This mosque was so poorly restored in the nineties that the work amounted to a demolition and rebuilding process that has resulted in the loss of much of its historical value.

Nāhyā streets have maintained their old planning in spite of the fact that the old buildings having been replaced by new ones

Some of the old buildings remain standing and demonstrate the traditional architectural style of Nāhyā

The ruins of the old Nāhyā school with its traditional architectural design is being replaced by the new school which was erected by the General Authority for Educational Buildings

Old buildings are disappearing due to lack of maintenance and are being replaced by modern buildings

Despite the gradual disappearance of this traditional style of architecture in the village, the fabric of the society retained its distinctive social cohesion. This social stability has engendered a high degree of pride among the village population as demonstrated by a number of self-help initiatives and by their effectiveness in alleviating some of Nāhyā’s problems – such as their garbage collection enterprise and the initiative to build two kidney dialysis units for village use. Nāhyā’s well-established families have been instrumental in all these projects. Through their effective efforts in involving the local administration and government organisations in the governorate in these initiatives and self-help projects, the Nāhyā villagers succeeded in forcing these authorities to provide the services lacking in their community.

Although the arable land has been reduced in size, agriculture remains a vital economic activity in Nāhyā, particularly due to its fertile soil which was a primary factor in the desire of successive rulers of Egypt to acquire it. In addition some of the villagers work in carpet making which the neighbouring village of Kirdāsa is famous for, as well as textile manufacturing. There is also in the village a number of cement brick factories which sell their product to the construction industry market of Greater Cairo. The relative proximity to Cairo has also made it a source of employment for members of Nāhyā village who commute daily to Cairo, despite the difficulties of transport between Nāhyā where they live, and Cairo and Gīza where they work.

What is important in Nāhyā?

Rural communities usually enjoy a fair degree of social cohesion and pride in family affiliation, and this is particularly true in the case of long-standing, well respected families. Nāhyā in particular enjoys a high degree of such pride and cohesion which could be traced back to the historical roots of the strong relationship established between the Zumur family and their locality. The importance of this relationship is brought into focus when it is translated into the public initiatives being undertaken by the village community. These initiatives could be developmental in nature, charitable, or to provide services as demonstrated in a number of tangible examples in Nāhyā at the present time. For example, the community cleansed the hospital hallway after it became flooded with sewage water, which the community believes is the result of a technical fault in the sewage network. Furthermore they went on and repaired this fault themselves. With respect to the perennial problem of garbage collection which is suffered by most local communities in Egypt today, one of the community associations implemented a project for the collection and recycling of garbage. The Nāhyā community has a widespread problem with kidney disease and through self-help initiatives water purification units and two kidney dialysis units were established. In addition, the Nāhyā community had a unique initiative which involved building a police station for the village and implemented a design that suited the needs and vision of the community.

In the new police station, the holding cells are airy and well finished which demonstrates compassion for the individual who may be detained there for any number of reasons. While the Commissioner’s office is spacious, the area occupied by his desk is only limited. This takes into account that most disagreements in the village do not arise between individuals, as is usual in other communities, but between two or more families. It was for this reason that it was deemed necessary by the community to make provisions for sufficient space in the Commissioner’s office to accommodate as many representatives of the families involved as possible. This particular example highlights that while the social makeup of the village has many positive aspects in engendering pride and cooperation between individuals it does also have some negative outcomes which may be obvious from the way some of these disputes between families arise.

During the recent political instability in Egypt, Nāhyā contributed its fair share to the turmoil particularly as it has a strong presence of organisations with religious affiliation – there are those geared towards providing social services such as the Judicial Society and those which are politically motivated such as the Muslim Brotherhood. Following the January 25th revolution in 2011, the village also experienced significant activities from youth movements and organisations such as the 6th April movement and the Popular Committees which focused primarily on security, raising awareness and public services.

This political activism and popular mobilisation did not stop at physical boundaries but extended into virtual space. Nāhyā al-Ghad 1 is the most salient example of this phenomenon. This is a journalistic experiment which was initiated by a group of youth and some of the village intellectuals in 2006 and was supported by a number of the residents. It was developed around an electronic site started by Nāhyā youth to express their views and reflect their daily affairs and concerns. “The problems and concerns of Nāhyā – be they water or electricity supply or transportation are at the core of the journalistic material, for this reason you will find an interview with the local council leader about the village’s problems, discussions with famous villagers, with service providers or with the artists among its residents.” This is according to a statement made by the founder of this electronic newspaper – Jamāl al-Darāwy, although the site, for unknown reasons, has not been updated since 2013 both on its original site and on its Facebook page. As for Facebook there is a noticeable variety and quantity of pages authored by the sons of Nāhyā about their village. Among them The Voice of Nāhyā (2181 followers at the time of writing)2 which is an electronic and printed newspaper issued by a group of Nāhyā youth. However, the widest circulation is enjoyed by pages with an Islamic leaning or of those supporting political groups with religious affiliations – including the ones with current news focus – such as Nāhyā Ultras (22192 followers at the time of writing) 2, Nāhyā News Network (21039 followers at the time of writing)2 and The Nāhyā Alliance for Supporting Legitimacy (19901 followers at the time of writing)2 which is a page that supports the Muslim Brotherhood as is clear from the title.

Although these electronic pages and videos that are prevalent on the internet are subject to stop working or to change their electronic sites (as is the case with “Nāhyā al-Ghad”) their importance not only lies in the number of followers or the wealth and variety of material about local communities which represents a prime example of “community journalism” but also as a genuine in-depth portrayal of daily life in an Egyptian village such as Nāhyā, with all its perennial as well as incidental problems and events and interactions within a local community. Such events may be overlooked or neglected amidst the more momentous events of the national scene.

What are Nāhyā’s Problems?

There are a number of problems which are shared by all Egyptian villages, and Nāhyā is no exception. There is a long list of problems relating to scarcity, deterioration, pollution or Governmental negligence in the village which the community is trying to tackle either through their own efforts or through actively pursuing the Government and local administration to fulfil their role.

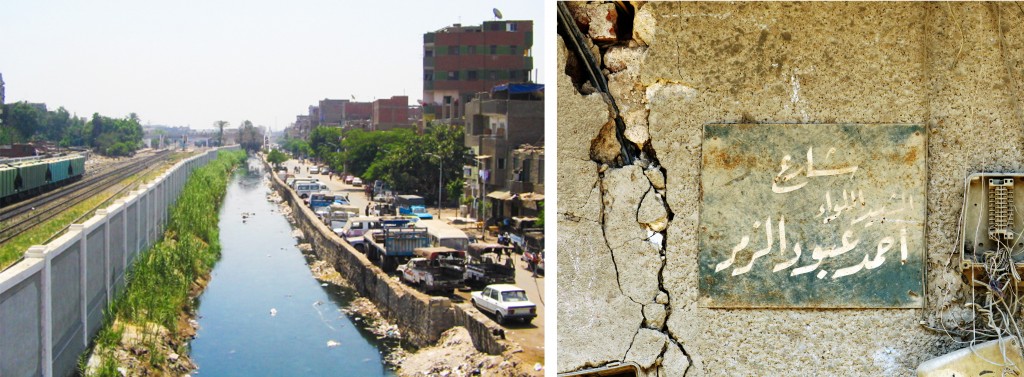

First on the list of problems is the severe lack of health services particularly in view of the fact that the polluted water supply has resulted in increases in the incidence of kidney disease in Nāhyā. The list also includes informal settlements on agricultural land which not only leads to the reduction of the arable area but also represents a burden on the infrastructure of the village – which is already degraded and run down and which in turn has resulted in sewage seeping into and contaminating the drinking water supply. This phenomenon together with governmental negligence and the use of waterways as dumping sites for garbage results in blockages and rendering the water unsuitable for irrigation. This forces the farmers to use subterranean water which results in increased costs for them and therefore more expensive produce. Other problems relate to the poor condition of the road network both within the village and leading into it and the absence of public transport between the village and Cairo.

While it is true that the Nāhyā community is notable for its initiative and cooperation which has allowed them to address a number of problems, the situation would have been much improved with concerted governmental involvement and extending the service network to include their village and its environs.

For example, the sole village hospital has a shortage of doctors and nurses such that new medical equipment donated by the Rotary Club is lying neglected and disused. The hospital consists of merely an out-patient clinic without an operating theatre or an accident and emergency unit. Until recently, the hospital building was covered in sewage as a result of a faulty execution of the sewage network and this in turn has led to the growth of a virtual forest of reeds to the extent of obscuring the hospital from view. The area became an ideal breeding ground for rodents, reptiles and insects. The situation would have remained the same had the village youth not taken it upon themselves to cleanse the swamp and remove the harmful vegetation. The sewage network itself was repaired through charitable donations from the community. At present, the doctors together with the community are trying to obtain authorisation from the Ministry of Health to convert it into a Central Hospital to allow it to serve the village population which is approaching 50,000 inhabitants. The Ministry has not responded so far (according to the residents) despite reassurances of their willingness to obtain the necessary funds. While waiting for the hoped-for approval, the residents have built two kidney dialysis units which were urgently needed but they continue to have to go frequently to distant hospitals.

Opportunities for Improvement

Any development vision in Nāhyā must rely in the first instance on the strong social fabric of the village which is a source of pride for its residents, particularly because it is these community bonds which continue to be expressed in public affairs and in civil work being undertaken and this is through political affiliation and community associations. This social makeup together with the political pluralism that has been engendered by the revolution has created a healthy competitive climate where everyone is trying to come up with instant solutions to the community problems and to provide the fundamental services that are lacking. This has encouraged the residents to more vociferously demand their rights and to lobby the governmental organisations to achieve their demands. This is what has been demonstrated by a number of initiatives in Nāhyā which have provided them with superior alternatives to those which existed before and which it is hoped will lead ultimately to improved conditions in the village.

However, in reality, this strong social activism in a village such as Nāhyā raises a number of questions and issues: -

Firstly: The absence of an effective urban policy which would deal with the village and rural communities in Egypt and would govern their relationship with the urban centres and preserve their special urban features, particularly for the communities such as Nāhyā which are situated on the outskirts of large cities. Some areas have already been lost to the fast-paced urban growth which has besieged and absorbed several such communities (for example the Muhandisīn and Mīt `Uqba neighbourhoods).

Official statistics reveal that residents of urban areas in Egypt in 2012 had reached 44% of the total population. This rate of increase amounts to 2% between 2010 and 2015 (the increase of population in rural areas is 1.4% and the average total increase in Egypt for the same period is 1.7%). These statistics reflect not only a constant rate of increase in urbanisation but also the assimilation of neighbouring rural and village areas.

There remains an important question: What is the Egyptian countryside?

What can we describe as urban and what constitutes the countryside in Egypt? What are the characteristics of each which would enable us to identify them? In reality, the distinction between the urban and the rural in Egypt is fast disappearing. Consequently, Egypt is gradually becoming entirely urbanised where the only differences are the size of the urban area, the degree of scarcity of services or its proximity to existing agricultural areas. A walk around a village such as Nāhyā would not reveal any distinctions between it and several urban areas in Egypt. Instead of laying down cohesive urban plans to preserve the character and distinctive features of such areas, current urban approaches aim to define the boundaries of cities – particularly those bordering agricultural areas – and in the absence of effective local administration, lead to the indiscriminate spread of the urban area and the disappearance of what once was “the Egyptian Countryside”.

Secondly: The relationship of the Egyptian countryside and its current urban and economic developments in relation to “food security” and “food sovereignty”.3

Current urban and economic policies appear to pose a direct threat to these two concepts in two ways. The first is the trend towards the mechanisation of agriculture which has driven a large percentage of the rural workforce to seek alternative employment in the urban areas or to supply the growing urban areas with the demanded building material and labour. The second is the relationship of the farmers with the agricultural land and water (as the most important elements of agricultural production) both of which are quickly dwindling. The arable area is contracting as a result of the spread of urbanisation due to the inability of the majority of the population to access government land suitable for building which drives them to build on agricultural land. As for Egypt’s share of water, it is also constantly diminishing, not to mention the unequal distribution of water among the different areas of Egypt, and the problems relating to the quantity and quality of water available to citizens.

The absence of sustainable and fair urban development or effective agricultural policies leads us into a vicious circle where the Egyptian countryside is gradually converted from “food production” to “urban production” through having to supply the current drive for urbanisation with the various requirements such as labour, building materials or land.

Thirdly: The relationship between local communities – such as the community of the village of Nāhyā – and the state. Despite the positive outcomes of the local community initiatives, for decades now the initiatives have been on the increase to the extent that they are becoming a substitute to the state’s core responsibilities. The state’s withdrawal from its responsibilities and roles led the citizens not only to provide themselves with habitable homes but also to provide basic services such as water and sanitation, together with a number of educational and health services, and even some security functions such as the police station in the village. It is not equitable for the local community to play the role of the state and excuse it from fulfilling its responsibilities. If this has become prevalent in informal settlements, its spread into the rural areas is even more noticeable. This widens the gap that already exists between the urban and rural areas, the bridging of which requires vast resources no one can provide except the state, not only because the state is able to call upon such resources but because the provision of such resources and their fair distribution is a basic human right.

As you browse some of the electronic sites, you may come across the pages of the “citizen journal” – which may relate to Nāhyā or other Egyptian villages. You will find that they are deeply involved in the locality, discussing issues that concern the area and its people, and reflect their various social events, take pride in their modest achievements and discuss their daily burdens of which only few of us are aware. You will find that it discusses the concerns of the absent Egyptian countryside – which is not too different from the village of Nāhyā – known for its name but not for its location.

Important Links:

Tadamun: Initiative for the Collection and Recycling of Garbage

First electronic site for an Egyptian village: “Nahia Dot Com”

1.The link refers to a copy of the site on archive.org and not the actual site. The site’s link indicates that it is no longer in operation!

2. This figure refers to the number of followers according to the electronic site at the time of writing this article

3. “Food Security” refers to ensuring access to sufficient food for the population but also includes the need for this food to be nutritious to maintain health. “Food Sovereignty” is not only concerned with ensuring sufficient access to food but provides a comprehensive alternative vision to ensuring access to foodstuff. This vision rests on food producers such as farmers, fishermen and herdsmen having the right to determine food production policies. It also depends on the strength they can muster in the face of the control exercised by the large multinational food companies in trading and marketing seeds and fertiliser. (Source: Why Food Sovereignty”, Halla Barakat, Mada Masr Website).

Comments