A “Better Life” for al-Minyā’s Rural Residents

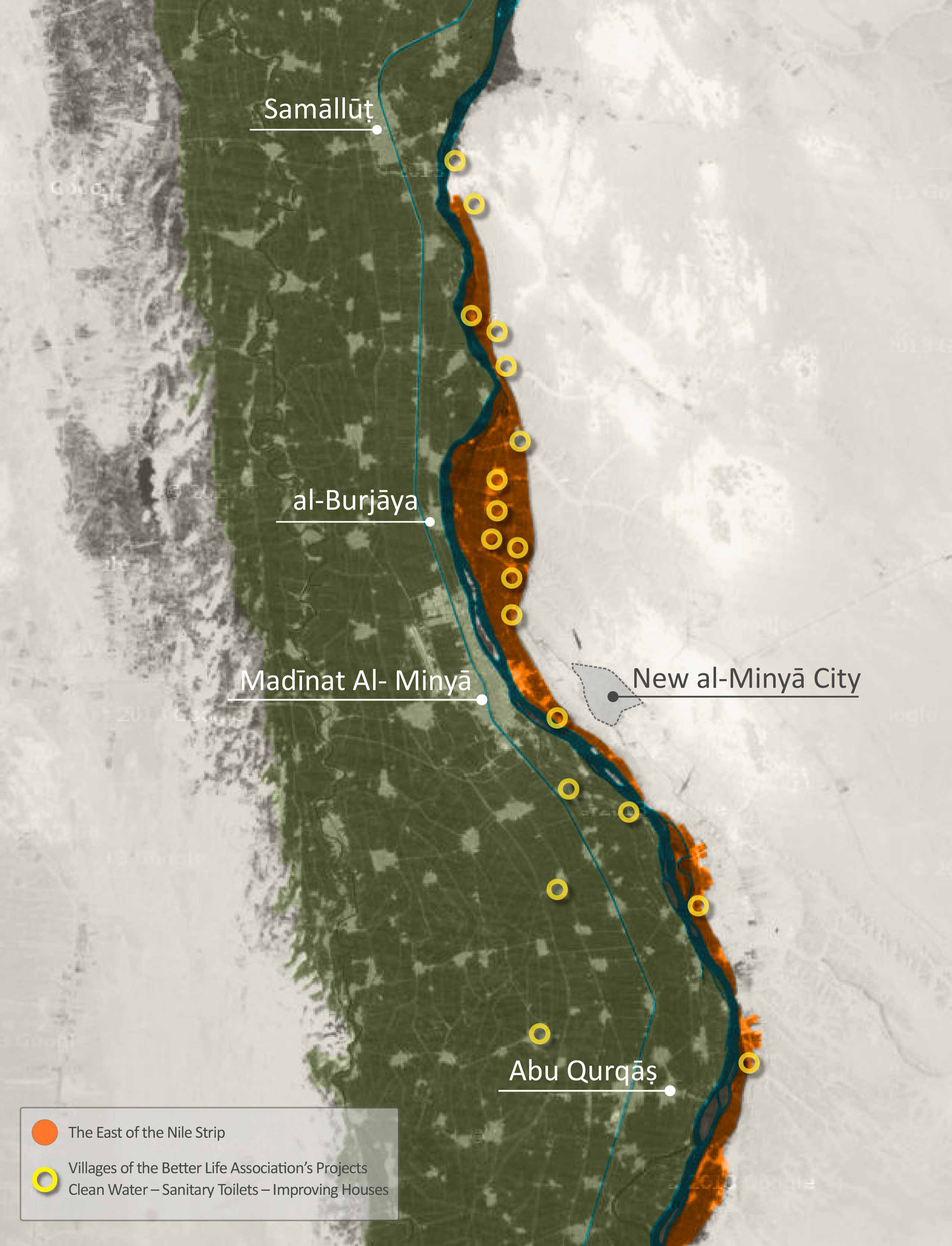

Between the banks of the Nile and the mountains of the al-Minyā governorate, a narrow strip of green agricultural land extends from the eastern bank of the Nile. Scattered along this stretch of agricultural land are villages which vary in size and in their residents’ economic activity. However, what all these villages have in common is their lack of access to public utilities, government neglect and a shortage of opportunities for earning a living. The impact of the work led by the civil society organization, “The Better Life Association for Comprehensive Development,(BLACD) which aims to improve housing, is noticeable in many of these poverty stricken villages; this work has been praised by the villagers, has won international prizes and has been covered by the media.

When visiting the villages with which the association is working, the signs of poverty are immediately apparent from the dilapidated condition of the houses and the modest appearance of their inhabitants. Most of the villagers work in fishing, agriculture, or quarrying. These occupations are similar in that they all involve seasonal, arduous work with very limited compensation. While villagers say that the conditions have recently improved, the conditions of the villages’ buildings remain extremely deteriorated in spite of recent governmental and local efforts to improve the resident’s lives in al-Minyā. These efforts began after 310 villages in the area appeared on the 2007 list of the poorest 1,000 villages in the country.

The situation remains extremely complicated and these efforts continue to be modest and lack proper planning and follow through. This creates an enduring need for serious programs to provide basic rights to these deprived communities. It is in this context that BLACD began it’s involvement through its program the Local Housing Movement which aims to house the poor in rural areas east of the Nile. The program started by providing services to improve housing and to provide access to public utilities. The next step involved training and organizing the residents and creating networks between local groups in order to safeguard their rights and hold government agencies accountable.

The women of the village divide daily trips to wash cloths, various containers, and household items in the Nile

Within the framework of the Local Housing Movement program, the villagers and the architects working on the program met in a participatory workshop to build a scale model of the local residents’ ideal house. The imagination of the poor was inexpensive—just a simple, two-story house which contained enough rooms to accommodate the members of the family and their various daily activities, such as a living area, sleeping quarters, and a pen for livestock. The model was exhibited during the celebration of the 2012 World Habitat Day, which was well attended by officials from the governorate. The villagers received the visitors with graffiti stating: “I wish to drink clean water”, “I want my son and daughter to study in safety”, “I need a sewage system”, “a roof to protect us from the rain and cold”, and many other demands that demonstrated the degree of urgency of the villagers’ needs and the poor housing conditions in their villages. Better Life has produced a documentary film featuring the villagers as they spoke about their inaccessible dreams—houses that preserve their human dignity. The makers of the film gave it the title Ordinary Dreams.

The Situation before the Initiative

At the initial stages of its involvement, the organization discovered that most of the houses of the villages had no access to potable water, sanitation or electricity. The residents and their families suffered from a number of health and safety issues due to the nature of the housing. The houses were built with unfired clay bricks and old roofs. The windows of these houses were also in a state of disrepair. The houses are not adequately maintained and as a result they do not provide protection from extreme weather conditions, insects, or other unsanitary factors. There is also no water system connected to the houses and no lavatories ,which force the residents to walk long distances to obtain water or to relieve themselves. As a result, most of these poor rural communities have suffered from severe health problems and lost any sense of security and dignity. In addition to these problems, some villages in particular suffer greater dangers due to their location. These villages are situated close to quarry sites where detonations in the hill quarries cause structural damage to neighbouring houses which are subsequently in great need of repair. In addition, because some residents do not formally own the land they live on, they face the constant threat of eviction by central government bodies that control the land such as the Ministry of Endowments. Other villages are situated close to polluting cement factories. While other residents have high voltage electricity lines erected in close proximity to their houses which not only prevent the residents from adding additional stories to their houses, but they also threaten the residents’ safety.

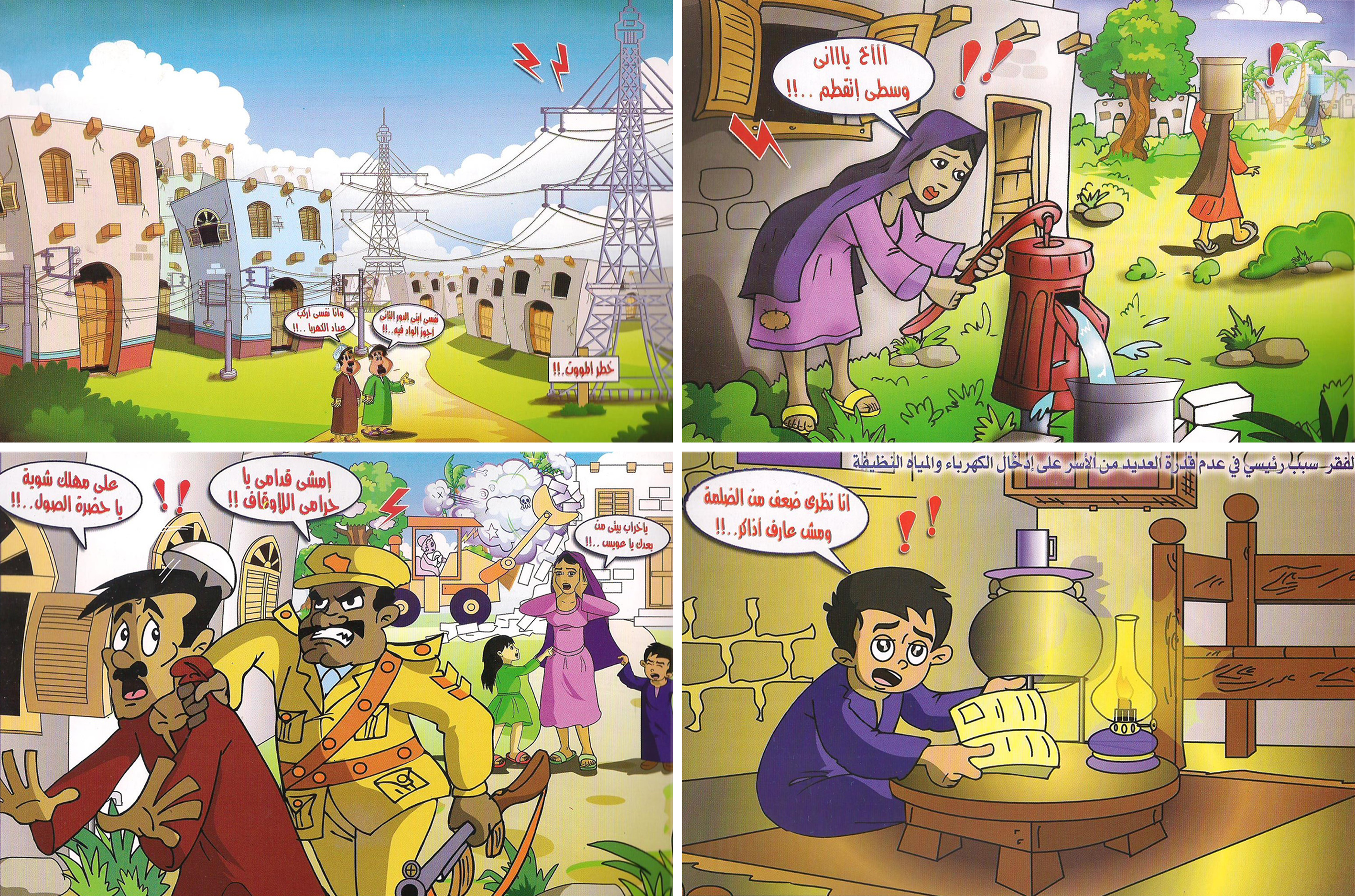

A booklet on the residents’ lost rights, one of the Better Life Association’s awareness publications.

The Beginnings of the Idea and its Development

At the beginnings of the nineties Maher Boshra, a resident of Nazlet El Shorafa, together with a group of educated villagers from the villages on the eastern bank of the Nile, established an organisation which aimed to develop local marginalized and poor communities and to improve their living conditions. After several attempts, In 1995 they succeeded in registering The Better Life Organisation for Integrated Development in al-Minyā as a non-profit NGO. Boshra currently holds both the position of Chairman of the Board of Trustees and Executive Director of the Foundation.

The right to an adequate house was one of the most important priorities of the organisation’s work. At that time, in the villages east of the Nile, there were no other organisations working in the field of housing in the governorate. The project started with simple interventions in the extremely poor Sawada village, followed by interventions in the village of Nazlit al-Shurafā. It quickly became apparent that there was a need to create a comprehensive program working on housing rights. The first program – implemented through the program The Local Housing Movement – was designed in response to the results of a needs assessment study carried out by the organisation in 1997 in a number of targeted villages on the eastern bank of the Nile. The study found that there were 3000 houses with no water pipes or sanitation. The first plan adopted by the organisation was to provide direct services to the identified individuals in need. They installed water pipes, taps, and lavatories in the houses, and financed these projects through grants to the families. In 1998 the organisation became more broadly focused repairing windows, doors and ceilings. These interventions then developed further to include the restoration of old and dilapidated houses and demolishing and rebuilding on the same sites, as well as building additional rooms or extra stories to fulfil the needs of the family to grow and expand. Within a period of 20 years, from when the organisation began its work until the present day, the Local Housing Movement program has continued to develop the types of projects and services it offers to address the various problems of the communities of the east bank of the Nile.

A residence in the village of Al-Gabal Al-Ṭir on the eastern bank of the Nile in Al-Minyā (The Better Life Association 2006)

Poor households were and are still lacking humane sanitation – the photo is of an opening under the stairs used as toilet in one of the villages of Al-Maṭahra on the eastern bank of the Nile. (The Better Life Foundation 2006).

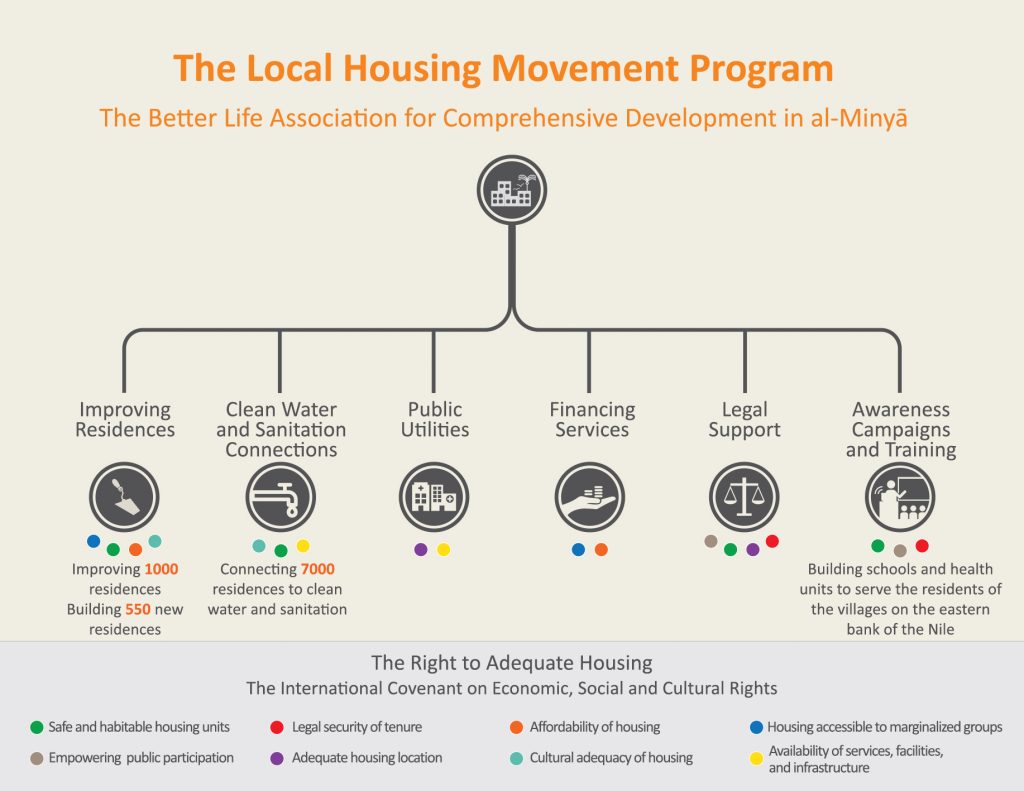

The Elements of The Local Housing Movement Program

The Local Housing Movement program focuses on prioritizing the needs of residents through participatory programs. Therefore, village residents implement the projects under the supervision of the program coordinators. Beginning in 2000, the organization has carried out its activities guided by the standards of adequate housing from the rights-based perspective in accordance with the International Covenant on Economic and Social Rights. In this framework, the program works towards installing basic amenities, ensuring structural safety, habitability, cultural adequacy and security of tenure. This work has been carried out through a range of programs that have varied in their objectives and characteristics. Some of these programs include:

- The House Improvement Project: this is the primary and largest project of the program. The project funds house improvement through microloans, and monitors the improvements from its inception to its conclusion. It also aims to train construction workers and house owners in the village to enable them to participate in the construction. The architects working on the project monitor the stages of construction and supervise its execution to ensure that it is carried out according to health and environmental safety standards and that the loaned funds are spent on the identified objectives and according to the priorities of the family.

- The project of supplying houses with pure water and sanitation systems: this program began with the project and continued its intensive work for the first ten years, as it was considered an urgent basic need in these communities. The program continues to work to supply houses lacking access to drinking water and lavatories. The project collaborated with government agencies in more than one village where the government undertook the construction of the main sewage and drinking water networks and Better Life then connected the houses to the main lines and installed taps and lavatories within the houses.

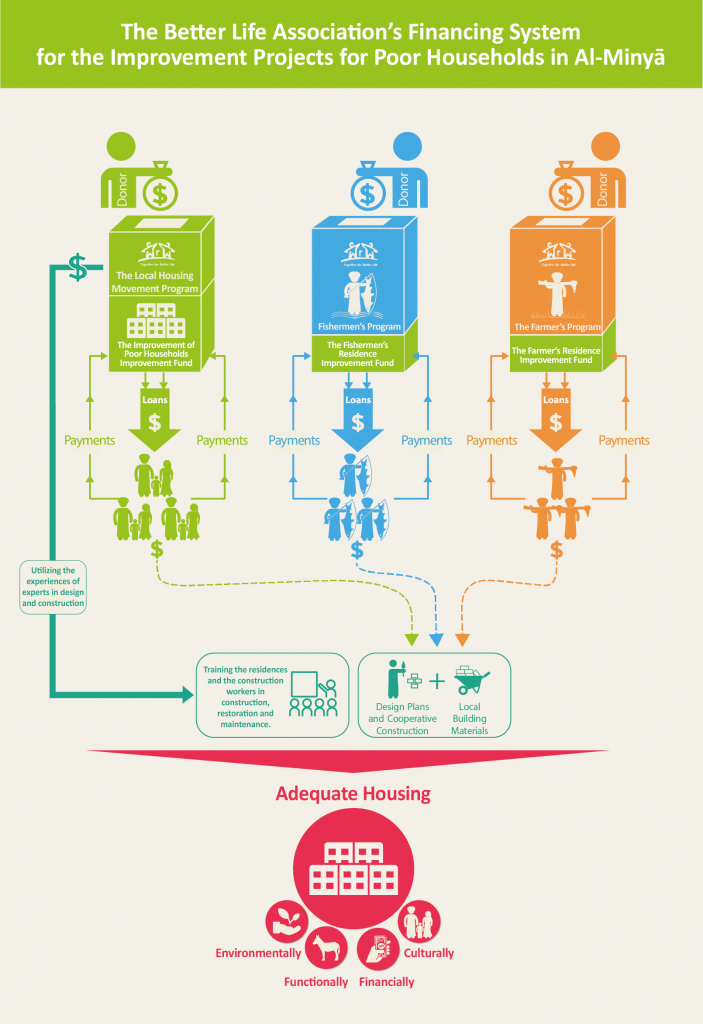

- Creating an adequate and sustainable funding system: the organisation has established a revolving loan fund1 as a funding mechanism that enables villagers to obtain a loan for the purposes of developing their existing houses or demolishing them and rebuilding new houses if necessary.

- Legal support and the organisation of communities: The legal support unit works with communities that are exposed to violations. It works towards acquainting them with their legal rights and helping them organize. This initiative encourages community members to discuss their problems collectively in order to reach solutions and engage officials in dialogue about these collectively formulated solutions. It is also responsible for filing lawsuits and supporting citizens in bringing complaints to government officials to demand their right to safe built-areas both in terms of tenure and structure, or in the case of life-threatening risks such as those posed by high voltage electricity towers.

- Programs for raising awareness and documentation which the goal of building a collective institutional and communal memory: the organisation publishes materials which document the housing conditions in the villages and the efforts of the local residents to develop their communities and homes. These materials contain success stories, training manuals and awareness-raising materials. These publications also include brochures, documentary films, and guides for training and capacity building of local communities. The Dalelee, Guidance Manual for Design Criteria and Construction in Rural Areas is an example of the training guides for management and organisational skills. In addition to documentation, this program publishes booklets using comic strips to raise the awareness about housing and other rights.

The Local Housing Movement of the Better Life Association for Comprehensive Development

The International Covenant on Economic and Social Rights

Resources and Funding

The Local Housing Movement program financed home improvements through a range of grants and loans that “Better Life” obtained and in turn lent to the poor in the form of microloans, ranging from one thousand pounds to eight thousand pounds. The local residents borrow the money from the organisation with promissory notes and with almost no other guarantees except the national identification card of the borrower and one of the residents of the village as a guarantor. The loans are repaid in affordable instalments over a period of three to five years, with an interest rate between 8% and 12%, which is determined by the organisation in-line with inflation2, administrative expenses, and unpaid debts. The organisation also covers the cost of some of the work to meet the basic needs of the poorest cases in the villages, such as supplying houses with water, installing lavatories, and some renovations to houses that are in danger of collapse. This work is funded by a grant to the family which does not have to be repaid.

At its inception, the program received a grant of $60,000 US dollars from the Dutch international aid organisation Oxfam Novib, which was the primary driving force of the project. This was followed by a loan of $68,500 US dollars from the organisation Habitat for Humanity, which was repaid over a period of five years. There followed a number of grants and loans from various international donors. The Better Life organisation led a unique and pioneering enterprise in the field, with the cooperation of the Egyptian private sector, to finance loans for the improvement of the houses of the poor, in which the organisation obtained a grant from the Egyptian Financial Group Hermes (EFG Hermes) company that helped in financing two large projects. One of these projects supplied water to the villages and the other project improved houses in the villages. Currently, the Local Housing Movement program is working with the support of the Swiss Drosos Foundation to finance loans for the installation of solar heaters.

The Better Life Association’s Financing System for the Improvement Projects for Poor Households in Al-Minyā

Challenges and Obstacles

Better Life has frequently faced great difficulty in obtaining funding for house improvement projects for the poor, either due to the international economic climate and the difficulty of convincing donors to prioritize funding for specific projects of the program, or due to the Egyptian political system and the restrictions it places on the work of civil society organisations. This is in addition to the absence of professionalism and transparency in local bodies, the time consuming bureaucratic procedures, the arbitrary treatment of requests by some government employees, and other factors that most often result in delays in granting permits and approval of projects. The 2002 NGOs Act 84 conferred a great deal of authority to government bodies enabling them to refuse projects submitted by NGOs, or to withhold allocated funds for periods exceeding the time set for the projects. Moreover there are other arbitrary procedures that reflect the lack of understanding in the Egyptian legislative environment of microfinance which limits the ability of organisations to develop their activities3. As a result of these factors, the association had to change the form of its legal registration from an NGO to a company. It also had to realign its projects in order to cope with the general conditions and restrictions imposed on civil work.

We also noticed that although the association tries very hard to work in accordance with the priorities of the citizens based on assessments of their needs, the priorities of the donors and their programs continue to influence the choice of the implemented projects to a certain extent. This is a challenge that is faced by all development projects in Egypt in general, even governmental projects.

Moreover, one of the most important challenges is the absence of a government strategy that genuinely seeks to ensure equitable housing for the residents of the rural areas in al-Minyā, which undermines the effectiveness of the program. The Local Housing Movement program aims to bring about change, which would be extremely difficult without the cooperation of government organisations. For example, the program can install a toilet inside a house, but cannot provide the whole district with a sewage network, so it has to depend in many cases on cesspools, the emptying and maintenance of which puts a heavy burden on poor families. Another example concerns the tenure issue, in which the intransigence of some of the central bodies such as the Ministry of Endowment in guaranteeing tenure rights to the residents and the inadequacy of Egyptian legislation in this area, represents a huge challenge to the project and an obstacle to achieving its objectives. In addition the high voltage electricity towers, the detonations in the quarries, and the polluting cement factories, represent recent hazards in the lives of the villagers who have been living in their villages for generations. Due to the flawed priorities of government entities, these hazardous activities were allowed to exist close to the villages and pose a threat to lives of residents without any consideration for their rights.

Results and Achievements

The location of the Better Life Association’s projects in the villages on the eastern and western banks of the Nile.

As a result of the project’s participatory methodology, it succeeded in recognizing the needs of the local communities. The project offered an in-situ upgrading model for the development of rural houses to provide a decent life for the residents.4 In spite of the limited resources and existing governmental restrictions on NGOs, the Improvement of Poor People’s Houses program managed to repair and improve more than a 1000 homes in the villages of the al-Minyā governorate in the last two decades. The program contributed in building more than 550 new houses to replace the old dilapidated ones and it provided more than 7000 houses with clean drinking water and lavatories.

The association also carried out several successful projects within the houses to improve living conditions for poor families. For example, the association upgraded traditional rural ovens to make them more suitable to health and environmental safety standards, and added extensions to the houses to accommodate growing families. Currently, the association is focusing on clean energy by working towards providing solar energy heaters to local residents.

The project also succeeded in organizing local communities. The project’s team participated in establishing several societies and unions for quarry workers, fishermen, farmers, women and other residents in the villages. All these groups have lauded the improvement of the living conditions and housing in their villages. It also succeeded in exposing illegal practices by local business owners. For example villagers and the Better Life association rallied against the owners of a cement factory near Banī Salim village, and successfully influenced the government to enforce the relevant laws and force the business owners to provide proper means of environmental protection and to reduce environmental damage that threatened the health of villagers.

As a result of the association’s work over several years in gaining the trust and support of the local communities and building a network of NGOs working within the villages of the project, the association and the villagers have succeeded in influencing government decisions, and in improving and motivating government performance. This has happened both directly and indirectly regarding local administration and the identification of development priorities. Following campaigns organized by villagers with the support of the association, roads have been paved and schools and health facilities have been built in specific villages. They also succeeded in obtaining promises from government officials not to forcibly evict people from the village of Nazlet Hussein, where the land is officially owned by the Ministry of Endowments. The villagers are still trying to legalize their tenure status. One of the main success stories of the association in this field is the local campaign it led with the residents of Nazlit `Ibīd in order to remove high voltage electricity towers from the village. The electricity towers have now in fact been moved away from residential areas.

Sustainability

Social Sustainability

The project has played a vital role in providing some of the needs of these rural communities, which are utterly deprived of their most basic rights. The funding system, which gives these families the opportunity to borrow, has provided not only a means of architectural improvement but it was also represents a quantum leap in the quality of life in the villages. An appropriate, clean house provides social status, a sense of security, and good health. Even though the funds these families borrow do not represent an overall increase in their limited monthly income, in fact there is a net reduction due to the repayment of loan instalments, the demand for loans continues to increase and the repayment percentage averages 95%. It is a fact that no association on its own can achieve justice in terms of equitable access to financial resources, especially if we look at the large gap between development and housing allocations for urban and rural areas. Added to this are the limitations placed on lending programs which serve those who already possess economic wealth and social means. However, what the project has managed to provide an opportunity – albeit a small one – for the poor in the targeted areas to gain access to some financial resources should they wish to. Indeed it prioritized the poorest and most vulnerable, taking into account the gendered dimensions of social injustice and the suffering endured by women in these communities, who are responsible for housework and raising the children, and thus the most affected by the lack of water, sewage and the dilapidated and dirty condition of the houses. Women are also the most vulnerable to violence and oppression. For example, women in these villages used to refrain from relieving themselves throughout the day waiting for the night to go out to relieve themselves. This lack of sanitary infrastructure, exposed women to many health hazards as well as the possibility of being sexually abused.

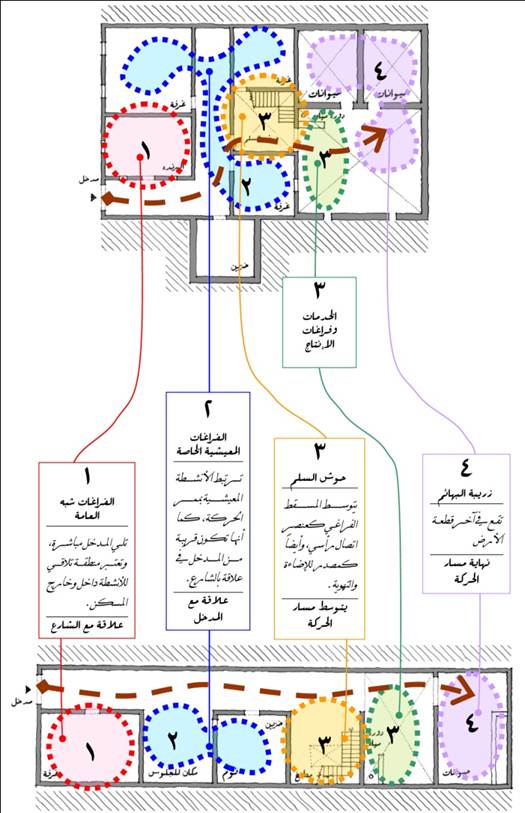

A study of the factors of movement, entrances, and the relationship with the street in creating different types of rural residences, which require public spaces, private living quarters, a courtyard, and a pen for livestock – Guidelines for design and intervention standards – One of the Better Life Association’s publications

It is important to evaluate the impact of the project in nurturing local organisations equipped with the skills to organize the local community around housing issues by entering into dialogue with official and non-official organizations. In this regard the Local Housing Movement program has adopted – as a primary target – the task of organizing communities and enabling them to implement projects through the work of the rural community itself. With time, and as they gained experience, the volunteers formed their own organisations in their villages to develop the village and to communicate with government officials. As a matter of fact, some of these organisations sought official designation such as NGOs, unions, etc.. The strategy of in-situ upgrading also allowed the maintenance of social relationships among families, which maintained the cohesion of the community.

An example of the project’s success in achieving social sustainability is the reinforcement of already existing awareness among villagers of the importance of their rights to land ownership. Additionally, the project has also succeeded in raising the awareness of government bodies of the dangers of government threats to land tenure and property.

Economic sustainability

Members of the family constructing the new wall by themselves – source: The Better Life Association’s Team

The project played a prominent role in encouraging the villagers to use limestone in construction projects because it is available in abundance in the governorate. Limestone is relatively low in price, as it does not require any transportation or additional costs. This has had a profound impact in reviving the domestic market. In order to be effective, the architects of the program, with the assistance of specialists’ expertise, trained local house owners and builders in construction techniques, so that they could collaborate together in the construction of houses without needing to hire external labourers. These efforts reduced construction costs by 50% or more. This practice familiarized a large number of local community members with construction and maintenance tools, and how to modify buildings, so that the local residents could improve their houses themselves in the future when necessary. Volunteers from the villages have also been trained in management skills, budgeting, and follow up and evaluation procedures. Therefore, this diverse range of experiences and cumulative knowledge gave the villagers professional development opportunities and opened areas of work and earning for them during the periods of time when their primary work is interrupted. This also ensures the sustainability of both material and human resources.

One of the important and effective factors is the integration of the house improvement component into other Better Life programs. This integration allows for the house improvement loans to form a part of a more comprehensive project to develop the life of residents and to increase sources of income.

Training the residences in construction methods that are easy to execute and inexpensive – Guidelines for construction workers in Al-Minyā – One of the Better Life Association’s publications.

The Better Life Association’s training sessions on the rights and the skills of organization and campaigns at the training center in the village of Nazlat Al-Shurfā’

Environmental Sustainability

As already mentioned, the project has worked on encouraging the villagers to use building materials such as limestone and sand which are locally available. When the project started, limestone was often used in construction, whereas now it is the most widely used material in construction after its gradual use and adoption by villagers. By reading the report of the consultants the association hired to help develop its work, we found that the association had paid special attention to the environmental aspects during its work and has continued to evaluate, use expert advice, and develop in order to achieve environmental sustainability.

Through training in methods of intervention, design, and construction of houses, the project enabled the local community to use the tools to control and upgrade their built environment in accordance with environmental and health standards. This involved ensuring that vents for air circulation were included and provisions for natural lighting inside houses were kept in mind as well as other criteria. Similarly, access to clean drinking water and the installation of lavatories in the houses contributed to reducing the incidence of illnesses within families and in particular among children who have suffered and continue to suffer from dehydration, liver, and gastrointestinal diseases.

Reflecting a deep understanding of the dimensions of environmental sustainability, Better Life has developed its projects to support the means of clean and renewable energy. This commitment to environmental sustainability is evident in how the current project promotes the use of solar energy in heat generation. In its first phase, the project has succeeded in providing 40 houses with solar energy heaters in one village and is planning to expand into other villages. In addition, the association plans to build an assembly plant for solar energy heaters in al-Minyā in order to reduce the cost of manufacturing which in turn would reduce the cost of the heaters for the local residents.

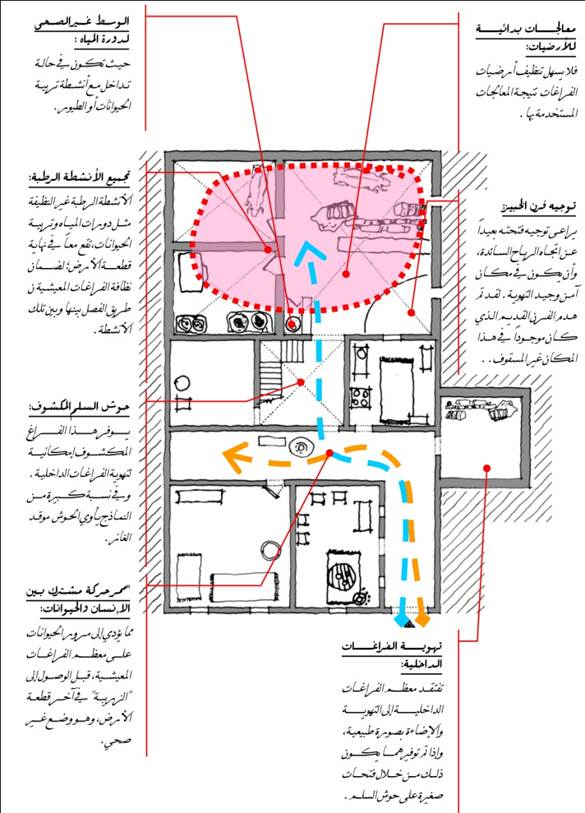

Analysis of the extent of environmental compatibility and the public health perspectives for rural residences – Guidelines for design and intervention standards – One of the Better Life Association’s publications

International Recognition

The Local Housing Movement program has received international acclaim. Donors recognized it as an example that should be followed; The Ford Foundation organized a program for the exchange of experiences between the BLACD program and organisations from Tanzania, South Africa, and the Philippines. Several international organisations working in the field of housing rights, such as Habitat International Coalition and The Global Network of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights commended the program and worked to disseminate its experience. The work of the program was also documented and published as best practice in 2008 by the UN-Habitat.

In 2010, the program received the World Habitat Award. The award which includes a prize of 10,000 euros is awarded annually by the British Building and Social Housing Foundation to two projects from all around the world which provide innovative and sustainable solutions to the challenges of housing in local communities. The award included a field visit by a team of international experts to inspect the work of the program in al-Minyā to learn from and disseminate the association’s successful projects internationally. The visit included experts and practitioners in the fields of housing, construction, and development from Bangladesh, Afghanistan, Chile, Pakistan, the Philippines, Jordan, Palestine, and Egypt. It also included Jasmine Al Wadhee, the Yemeni deputy to the assistant of the Minister of Public Works, Highways, Housing and Urban Development at the time.

Replication and Future Plans

From 2013 to 2017, the objectives of the association include enabling 5000 families to acquire equitable and affordable housing by either upgrading existing houses or rebuilding. The association has already achieved a large proportion of these objectives. The association has also worked with 100 local rural communities through training, raising awareness of residents’ rights, and urging residents to organize around and participate in managing construction. Finally, the planned objectives appear achievable. The Better Life association is substantially large in terms of both its volume of activities and its capital – currently there are more than 50 employees and 150 volunteers working on the implementation of its projects, as well as a network of NGOs and locally affiliated unions. The association also has future plans to collaborate with government bodies such as local authorities and water and sanitation organisations in order to achieve its long-term goals.

As for replicating these experiences, the House Improvement for the Poor project has proved, from the standpoint of those involved, that it meets the needs of a large segment of the residents of the neglected rural communities in al-Minyā. The expansion of the project activity to include a greater number of improvements to cover a larger section of residents in need is but one of many indications of the project’s success. Its geographical scope has also expanded along the eastern bank of the Nile and now includes select villages on the western bank. With that said, the gap between the growing demand for home improvement and the limited financial resources of the association remains. This gap is an important incentive for the organization to continue to spread its work and advocate for its replication and adoption by other organisations. The field of financing housing for the poor remains limited and restricted in Egypt in general and in Upper Egypt in particular. The few small funding organisations will often only provide loans and recover them – sometimes at exaggerated interest rates – without monitoring the quality of the financed construction. These funding organizations do not concern themselves with affordability, the cost to the poor, provision of facilities, or environmental and cultural issues. Therefore the Better Life association has a major interest in documenting and disseminating its experiences through a variety of means in order to encourage and support their replication by other development institutions among additional local communities in al-Minyā and other governorates.

TADAMUN’s Vision

The importance of the experience of the Better Life association is seen in how the association deals with the challenges of local housing both pragmatically and with a developmental perspective that incorporates the economic, social and cultural rights of the local community. The rural communities of al-Minyā, and Upper Egypt in general, suffered and continue to suffer from the consequences of poverty, deprivation and a lack of access to decision-makers. It is for these reasons that we are specifically interested in monitoring an experiment that has helped thousands of poor families and developed their homes through innovative practices—innovative in the sense that they differ from government development practices. These innovative practices emerged from the serious study of the communities’ needs and resources, and an understanding of how to utilize the existing resources to provide for the current needs as efficiently as possible. To put what the Better Life association is doing in context we will outline the nature of the current housing crisis that these communities are suffering from, the local residents’ share of the resources allocated to housing in the governorate compared to urban areas, and the available alternatives solutions regarding housing location and the funding system.

Rural Areas and Government Housing Investment Plans

One of the most important priorities which all government departments strive towards is social justice. The principle underpinning the establishment of social justice is the guaranteed access to basic services by every citizen anywhere in the country without discrimination between urban governorates, border governorates or those of the North or South, or even within a single governorate between urban and rural areas or between its provinces, towns and villages.

Opening remarks of the Citizen’s Guide to the Investment Plan 2014/2015

We agree that the fair distribution of the country’s resources is the first step in achieving social justice and sustainability in the widest sense. So what are the government’s plans to guarantee basic rights to housing and services for all citizens without discrimination? Do rural residents, particularly in Upper Egypt, enjoy even the bare minimum of these rights? How could this useful preamble be reflected in practical terms in the investment plans of the various ministries and what are their efforts towards achieving such objectives?

To start with, it is important to understand the realities of al-Minyā’s rural areas before discussing the articles of the Investment Plan of the Egyptian Government and analysing its implications.5 In reviewing government sources we find that al-Minyā is primarily a rural governorate. Out of the governorate’s 4.5 million residents, 3.6 million live in rural areas, which as a percentage represents 81% of the population. The proportion of those engaged in agriculture and fishing – i.e. whose lives and economic activities are closely connected to village life – makes up 47% of the total residents in the governorate. If we include working members of their families, we will clearly see the segment of the population dependent on village inhabitation for all aspects of their life. Statistical estimates suggest that 1.5 million of these villagers are poor, to the extent that 310 of their villages appeared on the 2007 list of the 1000 poorest villages across the country. If we look at multi-dimensional poverty we clearly see the degree to which the conditions of residence in these villages have degraded.6

If we are seeking social justice, it is clear that local authorities should prioritize development and guarantee appropriate housing rights specifically in the areas containing the largest numbers of residents and the areas which are most poverty stricken and therefore warrant the most support. However, in reality we found that the Egyptian government, as represented by the governorate and the Ministry of Housing, shows more concern for housing in urban areas at the expense of rural areas. This is demonstrated by the “New Minya” city which is the largest project to be carried out in al-Minyā since the end of the 1980s and is where most government investments have been concentrated. According to published reports, the population of the new city does not exceed 40,000 residents (5,000 according to other government sources). The intended target population is 157,000 by the year 2050—which is around 3.5% of the total population today— all of whom are city dwellers, either residents of the old town, or migrants from rural areas to the town. Some two billion Egyptian pounds have been invested over the last three decades to build their houses, providing them with public utilities and services and to plant trees along the streets of the city. In contrast, over 3.6 million village residents have to rely on community associations and modest self-help efforts to make incremental advancement in there living conditions by installing lavatories or running water within their homes.

Returning to the Investment Plan for the 2014/2015 financial year, we found that the largest share of investments allocated to al-Minyā out of all the ministries is that of the Ministry of Housing, which amounts to 35.5% of the governorate’s investment budget with an estimated value of 521 million Egyptian pounds. The plan refers specifically to the importance of the ministry’s projects represented by the National Program for Social Housing. According to available data from the New Urban Communities Authority about the National Housing Project in New Minya City, we found that the share for the publicised social housing projects does not exceed 2.5% of the total budget allocated by the Ministry of Housing. Moreover, the TADAMUN team located semi-deserted buildings in areas distant from the villages, which were listed under social housing. While the TADAMUN team was unable to obtain data about these buildings, we learned from a previous official at the governorate that the housing allocations for the governorate mostly go towards similar building projects and that the governorate’s remit does not include any attempts to improve the the quality of housing in villages. The important questions at this juncture are what is the allocated share for the village’s poor residents from these allocations and whether the social housing projects adopted by the Ministry of Housing represent a solution to the housing crisis in al-Minyā’s villages? Does the Egyptian government actively seek to address the situation on the ground in the existing villages?

Are Social Housing Programs the Solution?

Resident’s houses and community housing buildings from the governorate on the road to ʿAzbat Filibu – Al-Maṭāhara Al- Sharqiyya

It is clear that the state’s centrally-designed social housing system adopted is inadequate in the case of a rural governorate such as al-Minyā. It creates a rigid, repetitive model which fails to take into account the living practices of local residents. It invests millions in building residences while failing to address the local challenges and the demographic, social and economic characteristics particular to the governorate. What we find is that social housing in a governorate where 81% of the residents are villagers and are restricted to high-rise buildings which are not well suited to rural residents and their activities. They are located far from residents’ sources of livelihood either in the new desert towns or in dispersed plots isolated from the villages. As for cultural suitability, these buildings are completely alien to the cultural and social lives of the residents. The result is that these buildings are now either empty or have been allocated to people other than those for whom they were initially intended to serve. Moreover, obtaining a unit in the social housing projects is often governed by the terms of a mortgage requiring a steady income and regular employment. These terms, therefore, exclude the majority of the workforce in the poor villages of al-Minyā engaged in agriculture, fishing, or quarrying who fail to satisfy the necessary conditions and guarantees to access social housing flats. As a matter of fact, this system is not aimed at the poor or seasonal workers by any means which forces residents to seek recourse in alternative systems of finance suited to these types of incomes.

In-Situ Development and Alternative Finance Systems to Resolve the Funding Crisis for Housing for the Poor

There is no doubt that the provision of necessary funds is the main obstacle in the process of providing housing. To overcome this obstacle, a variety of mortgage systems have been designed. Microfinanced house loans are one of the methods utilised across the world to overcome difficulties associated with accessing financial resources from traditional financial institutions, such as banks, finance companies, and mortgage providers. These programs are specifically designed for the poor and those working in the informal sector as well as those who do not possess the deeds to their land or houses. The poor have resorted to these alternative financing options as a relatively available alternative which is preferable in comparison to relying on their own savings or borrowing from others. Microfinance systems have been implemented successfully in various areas around the world, but with their spread and propagation7 and the entry of profit-making institutions into the field, a number of shortcomings have come to the fore and there is now a widespread controversy around microfinance as a sustainable and socially just funding mechanism.8

In our view, we consider the importance of housing, and the sensitivity and urgency of its related problems, necessitates exerting every possible effort to ensure access to proper and adequate housing. The dilapidated conditions of the existing housing stock and its unsuitability to accommodate safe and healthy lives for the inhabitants, the growth of families, or their aspirations for social upward mobility are all urgent needs towards which the residents aspire to even at the expense of becoming entangled in a cycle of debt. We cannot deny that in many instances the preferable solution for the residents is to allow them to remain where they are living and to provide them with the means and guarantees that enable them to improve their housing themselves. Therefore it is clear that improving housing in-situ is a necessary and realistic approach in comparison with other solutions adopted by the government, which fail to produce positive results. It is therefore possible for microfinance to play an important role in resolving housing problems in many deprived, rundown areas. However, it is important to take into account that the new house, which yields no profit, does not automatically result in an improvement in the family’s income. Therefore, we find that the Better Life approach is more successful in comparison with other approaches because it takes into account a number of facets of the problem by using a holistic approach to total development in which lending is just one aspect of a complete package of measures such as training, assisting in completing construction efficiently and economically, as well as paying attention to the maintenance and the development of the residents’ trades and professions.

In terms of a general strategy for solving housing problems in areas such as al-Minyā, we should not depend solely on microfinance in improving the lives of the poor. We argue that it is necessary to carry out a radical overhaul of public economic policies in order to achieve a measure of social justice and to ensure they include proper protections. While microfinance can offer the poor access to financial resources and the freedom of choice available to the wealthy, it does not eradicate the effects of social injustice suffered by them. The poor continue to carry the burden of development themselves without being able to encourage the government to play its role in adopting a holistic strategy towards improving the standards of living as well as protecting and developing the sources of income for these communities and providing them with the necessary basic services and utilities.

Ultimately, we believe that the success of such approaches attracts the involvement of the private sector and residents in providing finance for renovating the houses of the poor. We hope that legislation and public policy aiming to generalize and implement such a double-edged sword would be accompanied by measures ensuring positive outcomes for poor local communities. Such measures should provide access to financial resources while at the same time guaranteeing protection from exploitation by high interest rates and developing parameters for the work of the lending institutions and monitoring lenders so that they do not become tools for impoverishment rather than for development.

1. The revolving loan funds are usually associated with microfinance projects. The fund represents the financial account through which all lending operations take place; sums of money are disbursed from it in the form of a small loan to the beneficiary and the repaid instalments are returned to the fund. These funds are then lent again to another beneficiary.

2. The average inflation rate since the beginning of the project until now is estimated to be about 8%. It reached a peak of 23.7% in 2008 (see: the rate of inflation in Egypt during the years from 1995 to 2015, according to the data of the Central Bank)

3. In an interview with Magdy Moussa, head of the microfinance sector in the Social Fund for Development, with the site Microfinance Gateway in 2011, he pointed out that the NGO law does not prevent the organisations from managing microfinance activities, but it does not include any provisions governing their work and it limits the ability of these organisations to obtain financing and to expand their activities. It is worth mentioning that President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi issued the Microfinance Regulation Law No. (141/2014), which appoints the Egyptian Financial Supervisory Authority to monitor the activities of microfinance organisations, but the results of its actual application are not yet visible.

4. In-situ upgrading is a strategy for urban development which has been applied for years and has proved to be successful in many developing countries, through developing marginalized informal districts in rural and urban areas in their area gradually and with the participation of the citizens. It is also closely linked to the legalisation of the conditions of the citizens and providing protection and safety to them instead of violating their rights and threatening them socially and in terms of their security.

5. The Administrative Division decides what is rural and what is urban in Egypt. Many researchers agree that there are shortcomings in this classification as it fails to give a clear picture of the conditions of the urban society, its size and its characteristics. There are huge areas of overlap now in the characteristics of the urban society. We will therefore find expressions such as ‘urbanisation of the countryside’ or ‘ruralisation of the towns’ demonstrating these mutual influences resulting from internal migration and numerous other factors. Moreover, standards applicable at the beginning of the last century are no longer valid. Villages are not necessarily reliant on the traditional occupations of agriculture and fishing. We do not possess a specific measure of the population density of what could be termed as a village. Therefore, in view of this muddled state, we cannot build assumptions on the nature of a particular society just by describing it as rural, we need further elaboration.

6. The multi-dimensional poverty index (MPI) is a tool that measures the various aspects of poverty rather than just the family’s income. It measures the three dimensions of health, education and living conditions. The latter includes a number of indicators that are directly related to housing, such as access to an electricity network and pure water and the presence of lavatories within the home and the suitability of the flooring of the house.

7. International organisations and most importantly the United Nations and the World Bank have been supporting and advocating microfinance for many years. The implementation of microfinance has been instrumental in achieving the developmental goals of the Millennium Development Project for eradicating poverty. Consequently the United Nations declared 2005 as the International Year for Microfinance with the intention of implementing it across the world.

8. In recent years microfinance became the subject of widespread controversy between concerned organisations. While it has been praised by development, its detractors believe that microfinancing does not improve the financial position of the borrowers but on the contrary leads them into financial difficulties. Consequently, they are imprisoned within the cycle of poverty for longer instead of being lifted out of it. Therefore its effectiveness in improving living conditions is questionable. However, with its propagation and the diversity of institutions offering these services and in the absence of clear rules governing the work of these financial institutions which have been misused and which have become a source of profiteering and money-making at the expense of the poor as opposed to giving them financial help, the overall evaluation of this tool has become muddled.

Comments