Professionalizing Local Administration in al-Minyā

When it comes to Egyptian local administration, the dominant narrative is one of inefficiency, incompetence, and corruption. Thus, it is quite a feat to see a local unit producing high-quality products and actually rivaling the private sector. Furthermore, within most government agencies salaries are quite meager and staff receive weak training, and so it is great to document a local unit training and paying its employees in a way that matches what they would have received in a private consultancy.

This article explores the process surrounding this positive development.

Situation before the Project

Egypt’s local administration approach is largely influenced by the traditional French governance model adopted in the 19th century where central authorities dominated over local ones. This approach is meant to increase central government revenues and to unify the counties. Egypt is divided administratively into 27 governorates, and each governorate is subsequently divided into cities and counties (known in Arabic as Marakiz). Government entities at the governorate, and city/county levels rarely have the resources necessary to run an efficient and effective operation.

The governorate administration hosts directorates that represent the various national ministries at the local level. The Housing and Utilities Directorate (which represents the Ministry of Housing and Utilities) hosts a Physical Planning Department (PPD), which represents the national-level General Organization for Physical Planning (GOPP).

Prior to the establishment of the unit in al-Minyā governorate, the relevant projects were implemented by the PPD within the Housing and Utilities Directorate. In 2005, the PPD was tasked with developing general and strategic plans for the governorate including detailed plans for all villages within al-Minyā.1 The department consisted of a General Director at the time, Eng. Souad Naguib, and two engineers – both of whom were recent graduates.2 Such an immense assignment would, no doubt, require substantial resources, which is why the governorate had the habit of contracting private consultancy offices – such as the al-Minia University’s Engineering Consultancy Office – to implement tasks that required resources the governorate did not have. However, this practice absorbed a substantial part of the governorate’s funds and did not make use of the department’s staff nor increase their capacity in any way.

The Project’s Idea

After speaking with her staff, Naguib found that they only intended to stay with the department for the six months necessary to become a contracted employee, after which they intended to request an unpaid leave and move to the private sector.3 This is no surprise, as their monthly basic salaries in the government were EGP 165, while they would be able to make around EGP 2000-3000 per month in the private sector.

The General Director found that the quality of work produced by her staff was very high and she could not see the logic in such high caliber staff moving to the private sector only to later participate in governorate projects through private consultanct firms. She brought this to the attention of al-Minyā’s governor at the time, Hassan Hemeida, and thus began the process of determining how to keep these highly qualified staff members within the governorate. This process was centered on a question: If the governorate relied on external consultancies to implement its projects, couldn’t an internal consultancy be set up within the governorate administration that would play the same role?

The concept was based on creating an internal consultancy office that the governorate could utilize rather than hiring private firms. The internal office would model itself after the Al-Minia University’s engineering consultancy office. It would operate as a professional unit, it would aim to produce the highest standard of work by intensively training its staff and constantly strengthening the unit’s resources, and it would pay its staff salaries comparable to the private sector. Thus, in 2005, the General Director of the PPD along with the Governor of al-Minyā decided to establish such an internal consultancy office – and so the Physical Planning Unit (PPU) was established.

Project Phases and Steps of Implementation

Since a unit such as the PPU was a first in Egypt, understanding the legal and financial aspects required for such a unit was of the utmost importance. The governorate hired a legal consultant to prepare the necessary documentation to ensure that the new unit would be legally sound. They decided that the unit would be set up as a governorate project and thus be allowed to generate income for the governorate. It would take advantage the governorate’s existing resources, while at the same time generating revenue, therefore having a double benefit. It would also provide incentives for highly-skilled staff to remain within the governorate rather than leave for the private sector. So, the financial and administrative system for the PPU was modeled after the system used for all other governorate projects. One of the main advantages of this model is the ability to set up a separate account for the unit, distinguishing its funds from those of the governorate’s general account.

A Board of Directors (BoD) – chaired by the governor – was set up for the PPU and tasked with facilitating all issues and decisions related to the PPU’s operations. The Board included financial, legal, technical, academic, and planning members. All PPU activities were to be communicated to the Board for approval. A decree was then issued by the Governor to officially initiate the PPU, as well as detailed job descriptions and responsibilities for all those staffed within the PPU. The PPU’s mandate was to provide physical planning services to the governorate administration and it would be contracted by the governorate as would any external private consultancy.

The General Director of the PPD, Eng. Soad, was assigned to head the PPU and they seconded the department’s engineers to work for the PPU in exchange for additional financial compensation.4 The unit would also get a percentage of profits generated by the projects they implemented, adding to the staff’s financial compensation.5

The PPU began by hiring consultants to conduct intensive training for the staff on developing detailed plans, conduct surveying, use GIS, and manage projects. They set up a surveying unit within the PPU equipped with GPS and other advanced equipment. Finally, they registered the PPU within the GOPP so that any plans they developed would be considered officially certified government plans. 6

Resources and Funding

When the PPU was first being set up in 2005, the Governor transferred a starting sum from its general account into the PPU’s private account. This was meant to cover the initial start-up costs until the PPU began generating revenue. All other resources were taken from the existing resources of the governorate and the PPD, including the office, staff, and initial equipment.

The PPU started implementing consultancies for the governorate – that were previously given to private consultancies – and the PPU started generating revenues – and eventually profits. Currently, 30% of the profits go towards strengthening the PPU through, for example, training and purchasing additional equipment, and a share is distributed among the PPU’s staff. The remainder goes into the governorate’s general “Services Fund” which is spent on providing services for al-Minyā’s cities and villages.

This has allowed the PPU to be equipped with the technologically sophisticated equipment that rivals private offices, which has in turn enabled them to carry out high-quality projects and hire experts to assist with tasks they cannot implement themselves. By the time Eng. Naguib left the PPU in order to join the Informal Settlements Development Facility (ISDF) in Cairo, the PPU’s budget had reached around EGP 15 million. Today the PPU’s project portfolio has reached around EGP 1 billion.

Challenges, Results and Impact

When attempting any innovative initiative within a government institution, the biggest obstacle tends to be finding decision-makers who are open-minded enough to welcome any deviation from the standard modus operandi. Thankfully, this did not represent a challenge for the establishment of the PPU due to the creativity and foresight of the PPD’s General Director and al-Minyā’s governor at the time. The main difficulty was the complexity of setting up the PPU’s financial and legal system, and ensuring that all its papers were in order. The PPU is monitored by the Accountability State Authority (ASA). In its early days ASA audits were particularly frequent, in part because it was a new unit and also because it received some complaints from competing entities. Because the PPU insisted on paying significant attention to its documentation and paperwork, all audits went smoothly and successfully.

In terms of results, the PPU has implemented many projects, including a new delineation of the urban areas in the entire governorate using satellite imagery to determine the old and new urban boundaries for all of al-Minyā. The PPU has also implemented large-scale construction works including building a bridge and renewing a tunnel in al-Minyā city. It also set up two bakeries for producing and distributing subsidized bread. The first central bakery was set up in Markaz Samalūt and distributes approximately one million loaves per day, the second was set up in the industrial zone of New al-Minyā. The logic behind establishing the latter was to make use of the Social Fund for Development’s pension in al-Minyā which received payments every month that were not put to use. The monthly payments were deposited in the bank and left to generate interest. But the PPU staff believed the money could be invested into something beneficial for the community and could also generate revenue for the Fund which would increase the sum that pensioners received upon retirement. The PPU decided to establish a small bakery for subsidized bread and it has been very successful in generating a substantial return on investment for the Fund.

Another project was to regenerate a piece of vacant land owned by the governorate that people had been using as a garage and storage. It was in a very vibrant location but it had been underused, so the PPU staff suggested to construct a private residential building on it. The cost of construction would come from the governorate’s Housing Fund and the revenue from selling the building would be returned back to the same fund. The construction cost a total of one million EGP, and the building was later sold for 8 million EGP, generating 7 million EGP in revenue for the Housing Fund that is meant to be spent on subsidized housing.

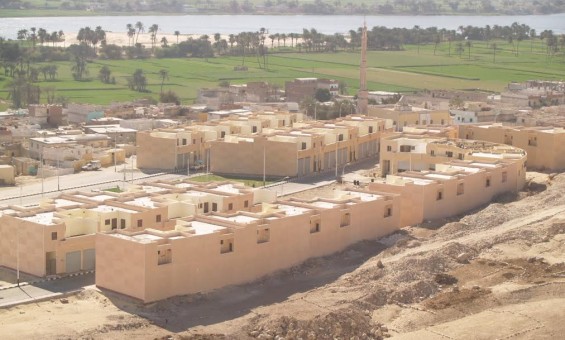

The PPU also constructed residential buildings in Markaz Matay and a building complex in Banī Mazār. It built Madīnat El-Hirafiyyīn (an area to house local craftsmen and their workshops) as part of a project with the Ministry of International Cooperation and it developed a shopping center along the walls of the al-Minyā Sporting Club to utilize the space. It constructed an administrative building for one of the governorate’s projects, and it constructed a building to house workers for one of the Agriculture Directorate’s projects.

Shopping center along the walls of the al-Minyā Sporting Club

(Source:Physical Planning Unit (PPU))

The PPU also renewed an important historical area called Shuhadā’ al-Bahnasa, which hosts Islamic, Christian, and Roman-era sites, but had deteriorated over time with little to no maintenance. The PPU cooperated with the Tourism Development Agency and the Armed Forces Engineering Agency to develop the area’s landscape and sites, as well as encourage tourism by setting up bazars and cafeterias. Next to the Bahnasa area, the PPU developed a new village in the desert hinterland called the New Bahnasa. There are now around 5,000 people (mainly youth) living there, and the PPU provides each resident with a home and 5 feddans for agricultural development.

Mosque (bottom, top-left), Cafeteria (top-right) and bazars (bottom-right) of an important historical area called Shuhada’ Bahnasa

(Source:Physical Planning Unit (PPU))

It is also worth noting that all of the PPU’s construction projects paid a great deal of attention to preserving the architectural style of the city and maintaining its urban harmony, which is something they felt distinguished them from a private office.

Many more projects have been implemented by the PPU and until today the PPU continues to implement high-quality projects and generate income that surpasses any of the other private consultancies because the entire portfolio of the governorate moved to the PPU. Although the PPU was set up as a consultancy office, it only works with government entities and does not take any projects from the private sector or NGOs.

One of the main long-term impacts of the PPU has been to preserve the governorate’s human capacity by attracting high-quality staff and provide them with incentives to remain within the governorate. The engineers that joined the PPU in 2005 continue to work for it today and have not moved to the private sector as they had originally intended to do.

The PPU’s wider-scale impact mainly lies in its model being used as inspiration for the Informal Settlement Development Units (ISDUs) that were set up in all governorates across the country in 2009.7 When Eng. Soad Naguib moved to the ISDF in 2009, one of her first recommendations was to set up governorate-level units that would be specialized in implementing informal area development projects, rather than such activities having to compete for the attention and resources with the governorate’s many other projects. Taking note of the PPU’s separate account, the ISDUs were set up with separate accounts so that they could receive loans directly from the central-level ISDF.

When it was time to establish the ISDU in al-Minyā governorate, the ISDF and the Governor of al-Minyā at the time considered using the PPU to carry out the informal area development tasks, rather than setting up a separate unit. However, they found that the financial system for the ISDUs was too different from that of the PPU, since the former received non-interest loans from the ISDF while the latter relies on its own revenue. Therefore they set up a separate unit headed by someone who was trained and worked within the PPU and is currently implementing the development of an unsafe area called `Ishash Mahfūz.

Sustainability, Replication and Future Plans

The ISDUs are not consultancy offices like the PPU, but rather governorate units that are responsible for implementing all projects related to informal areas in their governorates. Currently, the PPU model has not been duplicated in any other governorate. However, the long-term goals of the ISDUs include eventually converting them into consultancy offices such as the PPU. This conversion has not yet taken place, partly because it requires a governor’s decree to be established, and since 2011 the governors have been replaced very frequently – at times almost every year. However, through her new position at the national level with the ISDF, Eng. Naguib has continued being a vocal advocate for the implementation of the PPU model within the ISDUs. This has been mainly through conducting workshops and presenting the model at conferences and highlighting its benefits, including that the governorate completely owns the work, it develops the local administration and its technical capacities, it creates loyalty and a sense of responsibility among the staff, it gives them incentives to work harder, and it substantially reduces the implementation costs.

In the meantime, the ISDF is currently undertaking an evaluation and restructuring of the ISDUs in order to professionalize them to work more along the lines of a professional consultancy office, and it is heavily involved in their capacity-building.

TADAMUN’s Vision

It has always been difficult to find positive examples within Egypt’s local administration and TADAMUN believes that light must be shed on such examples when they exist. It is important that other government employees become aware that there can sometimes be spaces for innovation within government entities. There are opportunities, albeit minimal, for innovative people to flourish and such positive examples may give them the incentive they need to take advantage of such opportunities. It is also important for citizens to hear about such initiatives and to understand that positive things can take place within local government, and thus the public can raise its expectations from local officials and civil servants.

However, it is important to highlight that despite the successes of the PPU highlighted above, there has been no form of evaluation of the impact its projects have had. The PPU has not interacted with the residents of al-Minyā or made an effort to understand how the public perceives its projects. One example is the New Bahnasa Village, which was highlighted as a success by the PPU, but one news article paints a different picture. It is surely a positive (and rare) thing to see professionalism and efficiency within a local administration body, but such experiences cannot be considered complete without the oversight and participation of the people.

Related links

1. The national-level General Organization for Physical Planning (GOPP) is in charge of developing detailed strategic plans for all cities around Egypt, but the village plans are the responsibility of the local directorates.

2. Currently, Eng. Naguib is the General Manager of the Central Authority for the Upgrading of Informal Areas in the ISDF.

3.This is a common practice in Egypt such that it allows people to get private sector salaries while having the safety net of a government job to fall back on in case anything should happen.

4.“Secondment” is a term that refers to the process of assigning an employee temporarily to work for another organization or department. Read more about it here.

5. As detailed below, many of the PPU’s project’s generated a profit, part of which was distributed among the unit’s staff.

6. The detailed plan is usually the responsibility of the physical planning department in the governorates, and the governor (and local popular council when it exists) is the government authority who signs and approves it. Registration with the GOPP enabled the PPU to undertake the same task.

7. ISDUs were established on the governorate level and administratively report to ISDF at the national level.

Featured image: Madīnat El-Hirafiyyīn (Source:ONA)

Comments