Shubrā

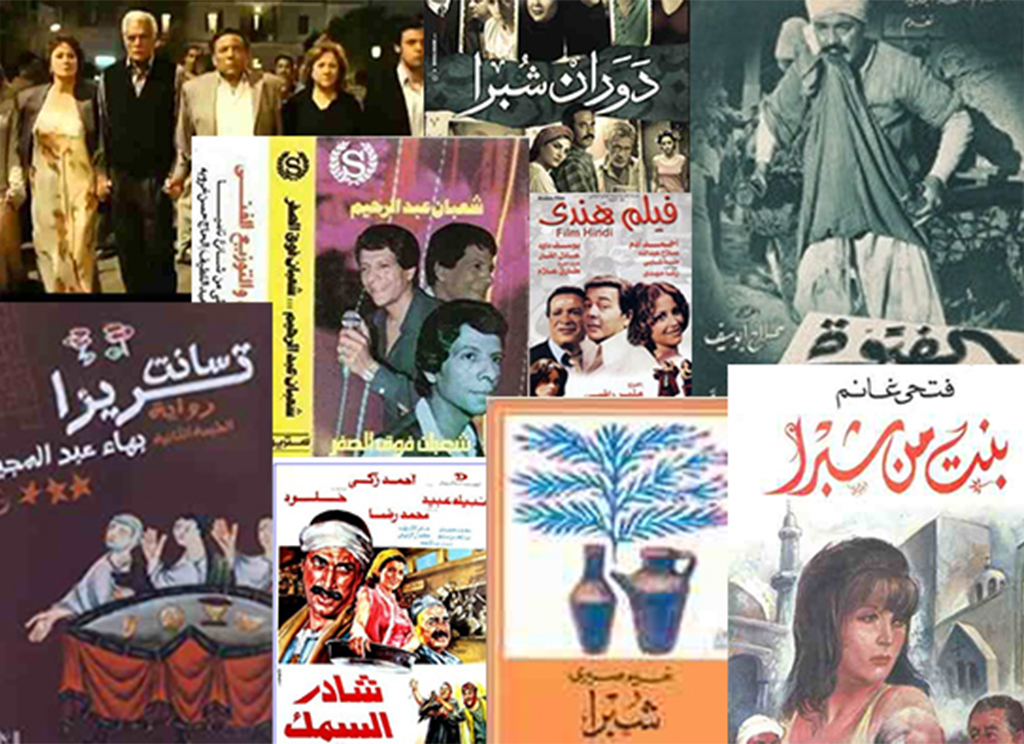

Among the suburbs of Cairo, Shubrā stands out with its warm atmosphere and unique character. Shubrā’s residents are proud of their neighborhood, so much so that some popular singers dedicate their songs to Shubrā and its people. Such songs established the residents’ reputation, which now precedes the area and its residents. For example, around 15 years ago, Shʿabān ʿAbd al-Raḥim wrote a song about the famous streets of Shubrā entitled “Aḥmid Ḥilmy” which was the start of his fame. He referred to ‘Aḥmid Ḥilmy’ marrying ‘ʿAida … the ceremony was performed by ‘al-Shaykh Ramaḍān’… the witness was “Al-ʿAssāl”… and they bought the candles from ‘al-ʿAṭār’. Similarly, Rikū praised ‘the Shubrā girls’ in his well known song.

You cannot mention Shubrā without remembering that it has the largest concentration of Copts in Cairo. In the past, before the Rawḍ Al-Farag market was relocated to Madīnat Al-ʿ Aubur, Shubrā was also famous for being the main market in the city. Shubrā is considered the main gateway connecting Cairo to the Delta, by virtue of its position in the north of the city with train lines and transport routes between the Delta, Alexandria and the capital. It is also the destination of the underground Metro line Shubrā–Al-Gīza.

However, in addition to its geographical importance and its special place in the hearts of Egyptians, Shubrā also has a rich cultural heritage, which encapsulates the story of the founding of modern Cairo and its development. The area, which at the beginning of the 19th century was no more than a virtually uninhabited hinterland with some cultivated areas around it, witnessed a population explosion during the course of the 20th century which made it one of the most heavily populated areas of Cairo. In spite of its reputation as having the largest concentration of Copts in Cairo and possibly in the whole of Egypt, the social fabric today includes a variety of social, economic, and ethnic backgrounds coexisting together. It is also worth mentioning that Shubrā recently emerged as an important place in the Egyptian revolution often cited as a clear example of national unity.

Shubrā in Numbers

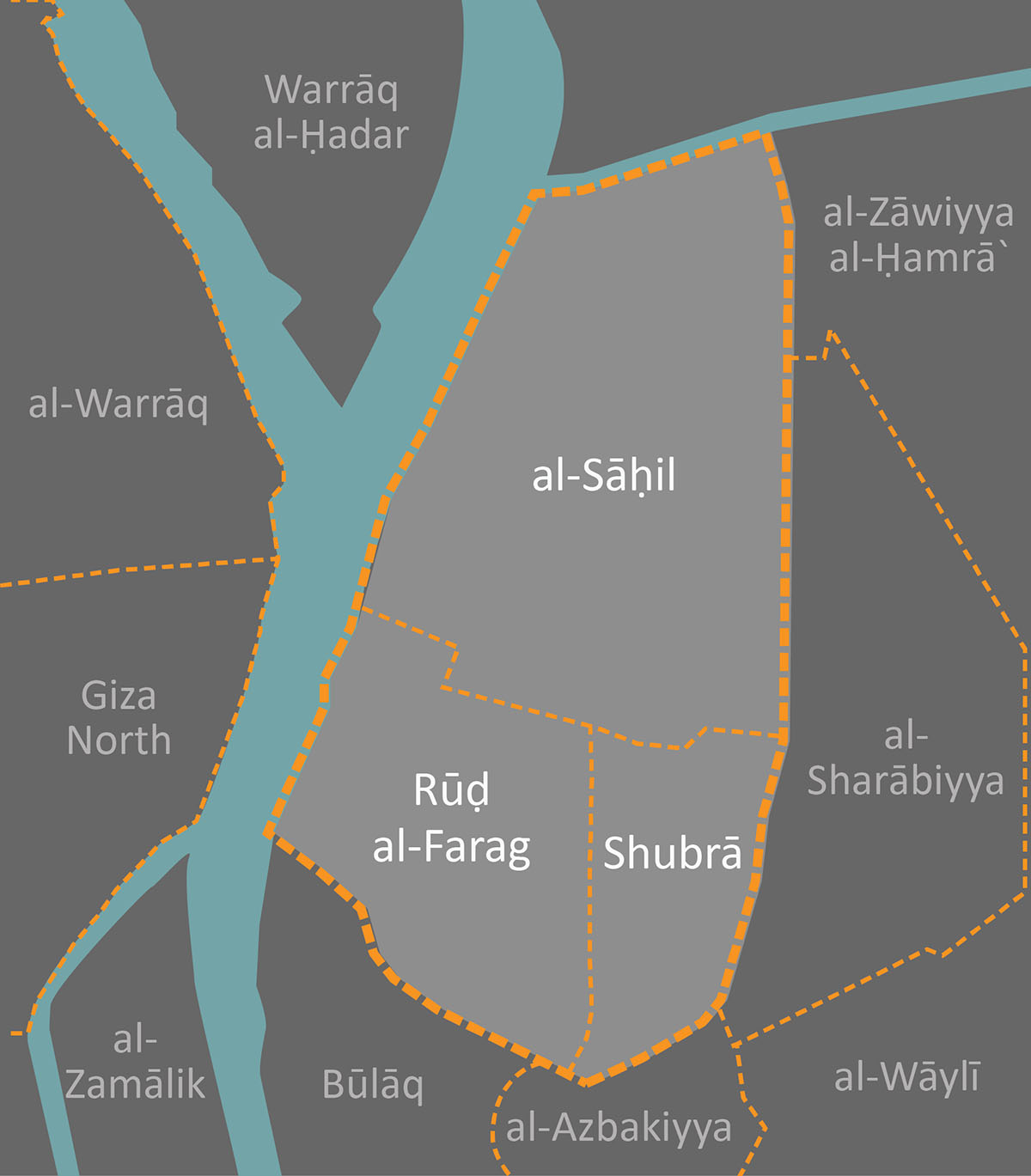

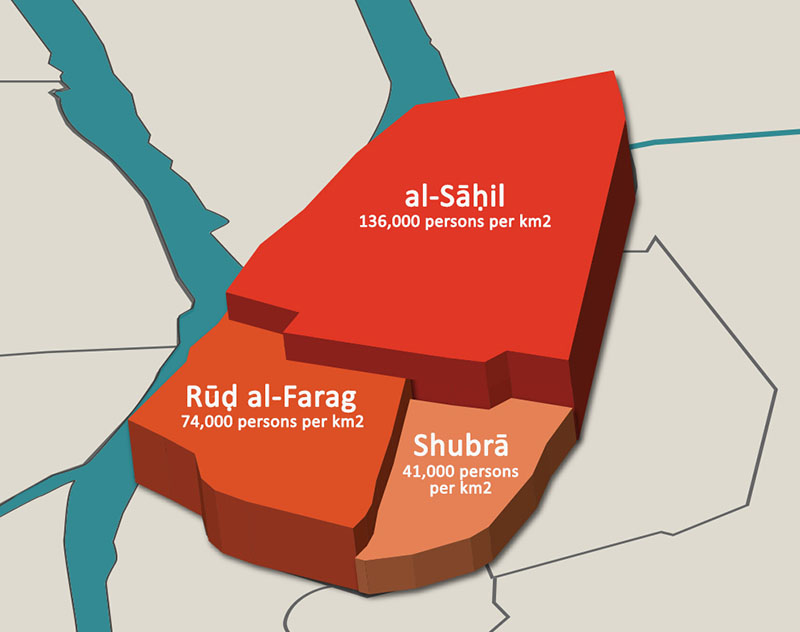

When we refer to Shubrā, we are in fact referring to three districts which come under the administrative authority of the Cairo Governorate. These districts are Shubrā, Rawḍ al-Farag, and Al-Sāḥil. But in this article, which discusses the Shubrā area and its administrative district, we will use ‘Shubrā’ in its popular Cairene usage and not to refer jus to the official administrative district. Cairenes refer to ‘Shubrā al-Balad’ or ‘Shubrā Maṣr’ to distinguish it from the administrative Shubrā district, which forms only a part of the area. Otherwise, residents of Cairo might merely refer to ‘Shubrā’ – in the absolute – due to its fame in contrast to the other ‘Shubrās’.

Governorate: Cairo

The District: Shubrā is divided into three districts al-Sāḥil,Rawḍ al-Farag, and Shubrā)

Total Area: 18.6 square kilometres (km2)

Population: 605,723

Shubrā Division: Total area: 2.8 km2 – inhabited area: 2 km2 – population: 81,687

Rawḍ al-Farag Division: Total Area: 5.2 km2 – inhabited area: 2.3 km2 – population: 167,653

al-Sāḥil Division: Total Area: 10.6 km2 – inhabited area: 2.6 km2 – population: 356,383

The Story of Shubrā

The origin of the name is thought to be derived from the ancient Egyptian word “Shebrū” which means hill or mound and which was switched in its Coptic usage to “Jebrū” which means farm or village. The Coptic “Jebrū” later changed into Shubrā, the current name. Shubrā was mentioned in Al-Maqdasī’s book Āḥsan Al-Taqāsīm as a village located between the two villages known as ‘Minyat Al-Iṣbaʿa’ and ‘Minyat Al-Sīrag’. Al-Idrīsī mentioned it on two occasions, the first time he referred to it as Sīrwā: “at the foot of Al-Fusṭāṭ there is the Sīrwā Estate which is a magnificent estate… where the honey drink, which is famous throughout the land, is made”. In the second instance he referred to it as “Shubrā” and in another edition of the book as “Subra”: “It is a village where the honey drink is made which is famous throughout the land and where the Bashanse tent is located.” We will discuss the Al-Bashans tent shortly but there is no doubt that the word ‘Sirwa’ as stated in the first instance is a distortion or an error on the part of the scribe of the word “Shebru” as mentioned in Al-Maqdīsī’s book. Muḥammad Bek Ramzy states in his “Geographical Dictionary”:

“It has become obvious to me that “Sirwa” is a distortion of “Shebru” and that they both refer to “Shubrā”. If you consider what was discussed by al-Idrīsī you will find that he copied “Sirwa” from a source other than the one he used to copy “Shubrā”. In spite of the difference in names due to distortion, each document has preserved the description of this village and the fact that it was the place where the honey drink was made and its position at the foot of Al-Fusṭāṭ (i.e. to the south of al-Fusṭāṭ City) because there were no significant areas of habitation between al-Fusṭāṭ and Shubrā. Al-Fusṭāṭ subsequently became a known point of reference.”

Shubrā as we know it did not exist prior to the 13th century. It was a small elevated area called Gizīrat Al-Fīl (The Elephant Island) – which we know today as Gizīrat Badrān – with its surroundings becoming flooded by the Nile water or the annual floods, which is referred to by Āmīn Sāmī Bāshā in his book “The Nile Almanac”:

“When the Nile flooded towards the end of the month of Epep and the dam was broken on the first day of the month of Mesra and it was opened by “Lajīn” the Prince of the Council, it had been a long time since the population had witnessed such an event because the floods blocked roads and bridges and submerged the lands of al-Minya, Shubrā, al-Rawḍa and the Cairo – Bulāq road (all of which at the time were Cairo suburbs and not an integral part of it), as well as Gizīrat Al-Fil and Kūm al-Rīsh and the wells overflowed. This all took place during the year 882.”1

“Shubrā”, which Āmin Sāmi Bāshā refers to, was one of the villages and suburbs which, at the time, fell outside the control of Cairo. It was stated in Tuḥfat al-Irshād that “Shubrā is one of the suburbs” and was known as ‘Shubrā al-Khayma’ or ‘Shubrā al-Shahīd’. In Tuḥfa it was also written that, “Shubrā al-Khayma which is Shubrā al-Shahīd is one of the suburbs of Cairo.” In the book “Endowments of al-Sultan al-Ghūrī” it is referred to as: “Shubrā Maṣr (Shubrā Cairo),” which was associated with Cairo because it was one of its adjacent suburbs. In “Laws of Ibn Mamātī” and in the book al-Intṣār, Shubrā was referred to as “Shubrā al-Khayma.” “Its Tuesday market included a market, a mosque, grain mills, ovens, oil presses for linseed and ‘Sīrg’ etc,” Sīrg refers to the oil produced by pressing Sesame Seeds. In the book Tāg al-ʿArūs, Shubrā is referred to as, “Shubrā Al-Makāsa because the al-Maks Tent was erected there,” which refers to the collection of Makūs or taxes.

But the al-Maks tent was not the only source for the designation of “Shubrā Al-Khayma”. In al-Maqrīzī’s topographical descriptions book, it is mentioned that “it is known as Shubrā al-Khayma, or the Tent or the Tents because the population celebrated an annual commemoration, each at their own level, in tents that they erected along the banks of the Nile in Shubrā in order to celebrate the Martyr’s festival there.”

As a result of this Martyr’s festival it was also called “Shubrā al-Shahīd”:

“It was also called Shubrā al-Shahid because in this village there was a small wooden box where a finger of a Christian martyr was preserved. On the eighth month of the Coptic calendar – Bashans – it was taken out and washed in the water of the Nile as they believed that the Nile would not flood if they did not throw in this finger. This festival was called the Martyr’s Festival (Eid al-Shahid) so it became known by this name.”

This rural or agricultural period in the history of the area – which is now known as Shubrā – is mentioned in history books in wich it appears that a large part of Shubrā belonged to al-Guiūsh garden that was established by the al-Afḍal Commander of the Forces Badr al-Din Al-Gamālī’. The garden extended northwards, east of al-Khalīg al-Maṣrī up to al-Wāilī, and westwards until Miniat al-Sirg (the present north western part of Shubrā). The al-Afḍal also established a beautiful panoramic view (the Fatīmids were fond of establishing such panoramas with pastoral views) and it became known as Manẓarat al-Baʿal. The Fatīmids had two other panoramic views in the area. The first was Manẓarat al-Tāg and the second was Manẓarat al-Khamsa Wuguh. Until today we can glimpse some traces of this distant past in the names of some of the streets and squares in Shubrā. From al-Turʿa al-Bulāqiyya Street – one of the major streets in Shubrā. A number of streets branch out: al-Manẓarat, al- Wuguh and al-Guiushi. At the end of the streets branching out of the right side of al-Turʿa street we find a small square called the al-Afḍal Square.2

In the 19th Century, Cairo expanded to the north and north-west which resulted in the appearance of new regions that had previously not existed. This expansion was a consequence of the phenomenon of the annual accumulation of deposits of silt carried by the floods, which was due to the changes in the course of the Nile. Up until that century, the districts of Shubrā, Rawḍ al-Farag, and Bulāq did not exist as these areas remained uninhabited until the start of the era of Muḥammad ʿAli.

Muḥammad ʿAli is credited with the development of Shubrā and its enivroment in 1808 when he selected the location for the construction of a large palace. André Raymond believes that Muḥammad ʿAli, who cherished living in the countryside, contributed to the subsequent urban development and in establishing a number of promising urban districts through building himself palaces in the countryside. In line with Raymond’s analysis, it was the palace and garden that Muḥammad ʿAli built in Shubrā which spurred development of the area.3

Muḥammad ʿAli chose a village on the banks of the Nile, Shubrā al-Khayma, to build his palace, where he allocated an area of 50 feddans in “a large area extending to the al-Ḥāg Lake.” In doing so he requisitioned a number of villages and fiefdoms.4 Some sources state that the construction of the palace was undertaken in a number of stages starting in 1808 and concluding in 1821, with further extension work continuing until 1836.

In 1847, one year before the end of his reign, Muḥammad ʿAli ordered “the construction of a wide road between Cairo and Shubrā.” This implies that until that date, Shubrā was not considered a suburb of Cairo, but as a distant outlying district necessitating the construction of a road between it and Cairo. This road is now the beginning of Shubrā Street and was called at the time Gesr Shubrā (Shubrā Bridge). Muḥammad ʿAli’s vision for this street was to create an area for recreation and relaxation, hence his instructions that this road should be wider and straighter than any other road in Cairo at that time.

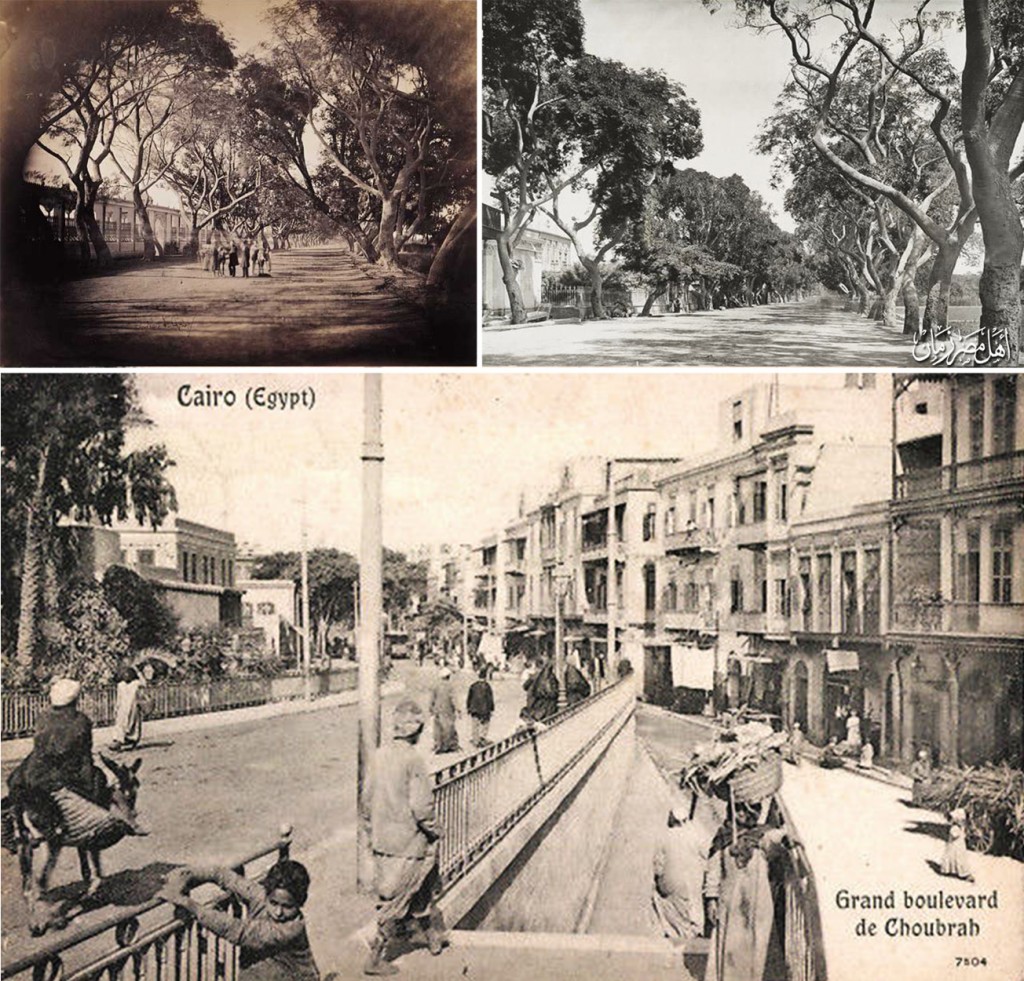

This road extended between Shubrā and Qanṭarit al-Laimon in Cairo. Albizia and Sycamore trees were planted on either side of it. There were instructions to sprinkle it with water twice a day morning and evening to refresh the air in the summer and to settle the dust in the winter. Workers were appointed to maintain the cleanliness of the street and to tend to the trees. Muḥammad ʿAli directed members of his family and the notables and wealthy in the society to build their palaces along the street thus making it of outstanding beauty. This prompted Gérard de Nerval, the French poet and traveller to describe it as “undoubtedly the most beautiful street in the world.”5 The street became the escape of the elite from the locals and the Europeans living in Cairo at the time, so much so that some of the French travellers and European visitors described Shubrā Street and its gardens as the Champs-Élysées of Cairo where the lifestyle was more western than eastern; the street was…

“A hundred times more beautiful than Hyde Park in May or June: Egyptian peasants on donkeys – their favourite ride, horses – of Arab or English breeds – ridden by swaggering Turkish Becks and Jewish bankers who remain the most stylish; a jostling throng consisting of an array of horse drawn carriages; from those full of tourists on tour with the Cook Company, to the fastest light Victorian carriages made in London or Vienna, the Khedive’s harem accompanied by their private retinue, Polish Countesses and those arriving from Monaco to cavort with the bachelors (European) staying at Shepherd’s or the New Hotel.”6

Accordingly, Shubrā became the preferred residence of the ruling family and the aristocrats as well as a destination for recreation and exercise frequented by the citizens of Cairo. Some of the most noteworthy palaces were the palaces of Zainab Hānim, daughter of Muḥammad ʿAli, the palace of Injih Hānim, wife of Muhammed Said Pasha, the Viceroy of Egypt, and the palace of Ṭusun Pasha – after which a street in Shubrā continues to be named. This palace has now become the Shubrā Secondary School and so has the Nuzha Palace, which was the place of recreation for the Khedive Ismaʿil. It was also used as a residence for dignitaries and is now the Tawfīqīyya School. Chicolani Palace has also been converted into a school.

Shubrā Street maintained its beauty and splendour until 1869 when the Khedive Ismaʿīl invited kings and ambassadors for the inauguration ceremony of the Suez Canal, when some of the Albizia trees were uprooted and replanted on the road leading to the residency of the French Empress Eugenie in Giza Palace (the present Marriot Hotel). A further number of the trees were also replanted along the Pyramid Road. In the Tawfīqīyya Plans, ʿAli Mubārak states that there remained some Sycamore trees, in the year 1890 when he wrote the book, at the end of the road close to Shubrā al-Balad, but with time these also had disappeared.

Shubrā Street during various periods where lines of trees could be seen on either side of it giving it a distinctive stylish look in the early days. Some palaces surrounded by gardens, which at one point extended along the length of the street, can also be seen.

However, despite this decline in the upkeep of the area as a seat for the ruling family and its royal retinue, developments did not cease in Shubrā.

At the end of Muḥammad ʿAli’s rule in 1848, the foundations for Shubrā’s development were already laid down. Moreover its proximity to Būlāq, the primary port in Cairo, influenced it greatly. Between 1818 and 1834 Būlāq became a large industrial centre due to the developments that occurred when Muḥammad ʿAli selected it for the establishment of a number of new weaving factories, a metal foundry, an engineering school, and a printing press – which for a long time was the principal press in the country and which continues to be known as Būlāq Printing Press. This led to an increase in the volume of river transport and a growth in the population of Būlāq. With the opening of the first train station in Cairo in 1856 in Bāb al-Hadīd (now Cairo Station on Ramses Street) the area started to attract migrants from the villages and from outside Cairo, most of whom chose to settle around this port. This economic and urban activity encouraged the steady expansion of Cairo northwards towards Shubrā.7

In spite of all this, Shubrā was still not considered an official part of Cairo. According to the law set out by Ali Mubarak in 1868, when he was minister for Public Works during the reign of Khedive Ismail, Cairo and its environs were divided into four areas within the Capital itself and four others in its neighbourhood. Shubrā was one of these outlying areas according to this law together with Old Cairo (Fusṭāṭ), Bulāq and Wailī.8

These major developments during the reign of Khedive Ismaʿīl were the product of comprehensive planning and a dominant central authority. When the city came under the de facto control of the British occupation – their era being characterised by awarding individuals the responsibility to take the lead in this development – the British Authority introduced a new system for urban development which relied upon the allocation of large government-owned tracts of land – not yet apportioned – to private owners who were to become responsible for the partitioning themselves. As a result of the increasing demand for the purchase of these tracts for building development, the British Authority expanded the land area by adding to it the large gardens in the outlying areas and a number of rural plots “suitable for building development”, as well as large tracts of land in the urban areas. Shubrā enjoyed a special position which attracted the British because of the ease with which it lent itself to this process of division, which was prevalent throughout the city and its surrounding areas. When the ruling family abandoned Muḥammad ʿAli’s palace as their base by the beginning of the eighteen eighties in the 19th century, aristocratic owners abandoned their properties along Shubrā Street as well. By the end of that century several palaces and gardens along this street – which were the favoured aristocratic residential and recreational areas – had become deserted and therefore coveted for urban development purposes.9

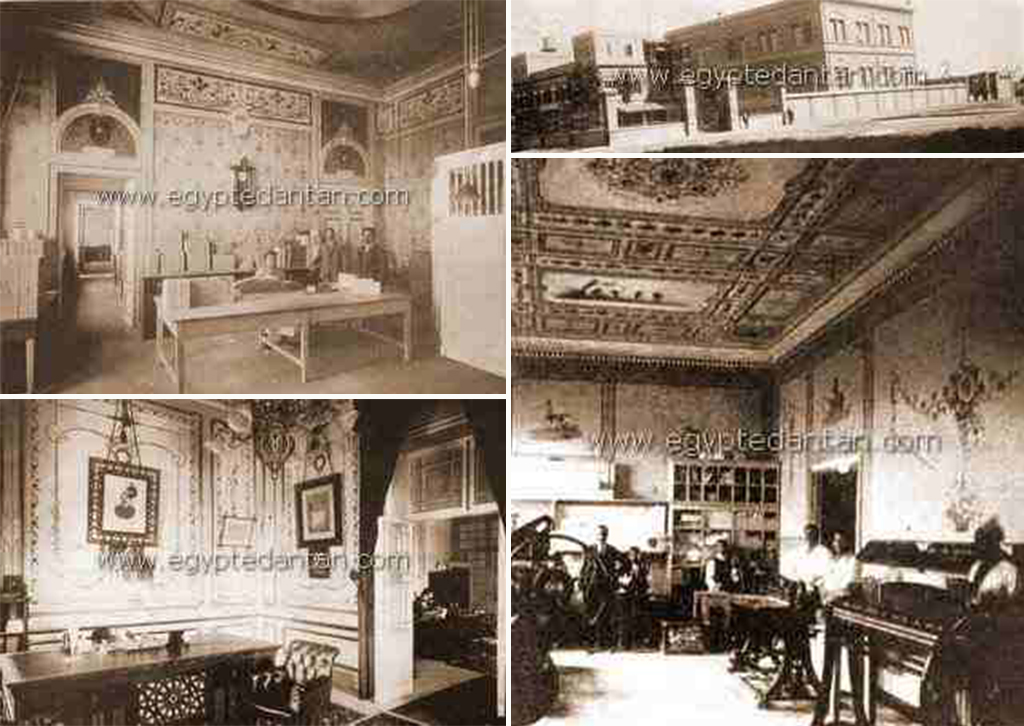

In his book about the recent urban expansion in Cairo resulting from the measures imposed by the Khedive as well as the interference of private companies, the author Jean-Luc Arnaud gives as an example Chicolani’s Palace. Following the completion of this palace in 1873, it quickly fell into disrepair and by the beginning of 1906 it was used as a cigarette factory. A few years later its grounds were parcelled into building plots. According to Arnaud, the cigarette factory in Chicolani was not unique in Shubrā. By 1907 there were six cigarette factories. These factories had a dual effect. Firstly, the need for a large workforce resulted in an increase in demand for low-cost housing. Secondly, there was a net reduction in the overall area occupied by private gardens due to a fall in their value which was a direct result of the newly discovered function for the deserted palaces which were then offered to private buyers for redevelopment.10

Pictures of the ‘Nestor Ganaklees’ factory at a time when the famous Chicolani palace in Shubrā was converted into a cigarette factory

With the beginning of the 20th century, the appearance of the area was being transformed due to the arrival of modern means of transport into the country. In 1902 the new tramway was extended into Shubrā. In 1903 the automobile could be seen for the first time in the streets of Cairo. Ramses Street (Abbās the First Street at the time) had been built during the reign of Abbās Ḥilmy the First – the second ruler of Egypt from the Muḥammad ʿAli dynasty – in place of al-Khalig al-Maṣrī (al-Nāsirī) which had been filled in as part of the renovations introduced by Muḥammad ʿAli. As a consequence, and with the continuing expansion of the city northwards, reaching Shubrā no longer presented a difficulty for the majority of the inhabitants of Cairo. Shubrā, therefore, continued to expand and to undergo urban development. By 1912 it was connected to Cairo via four metro lines (out of a total of 20 in all of Cairo) as well as three bus routes.11

When the First World War (1914-1918) started, Egypt took part by virtue of the British Occupation. Local industries benefited from the conducive environment resulting from the war. On the one hand, the population needed food and clothing and on the other, the army of the British Empire was in need of a number of manufactured goods, particularly textiles. The clothing industry attracted great attention especially following the suspension of clothes imports from Germany and Austria which had dominated local markets at the time. Even the Tarbush itself was imported from Austria. In response to this increased and persistent demand within the Egyptian market, a number of factories were built in Cairo and in other areas of the country such as Qahā. Shubrā was one of the areas where textile and clothes factories were established. For example, a hat factory was built in 1916 as this industry was well-established before the war, particularly the production of military headgear worn by the British armed forces.12 Similar to nearby Būlāq, in Shubrā a need was generated for local living quarters for the labour force working in these factories. Most of the workers came from villages following the decline of agriculture as a consequence of the economic situation brought about by the war.

The waves of migrants were not limited to Egyptians only. During this period members of western and eastern communities, subjects of the Ottoman Empire, which Egypt was technically subordinate to, settled in Shubrā. These included Syrian communities who settled in the Gazirat Badrān area where one of its most important street continues to be called Quṣūr al-Shawām (or Qaswarat al-Shawām) [palaces of the Syrians]. The most notable of the western community settlers were the Italians and Greeks who were concentrated at the entrance of Shubrā towards what is now Ramses Square. There was also a large concentration of British citizens to the extent that when Queen Victoria, the Queen of Britain, visited Egypt she also visited Shubrā Street to check on the conditions of the British community in Egypt. French citizens also settled in the area now known as al-Beʿtha Street (Mission Street) – which was named after the presence of the mission of French Catholic Monks who built the church of Saint Mark. The French founded two schools annexed to the church – Notre Dame Des Apotres for girls and Saint Paul for boys. A few other foreign missionary schools were also built, among them were: Bon Pasteur, Maria Ausiliatrice, Jean Paul, the Italian Don Bosco and others. These schools were built to educate the children of the foreign residents and most of them remain in operation today educating Egyptian children.13

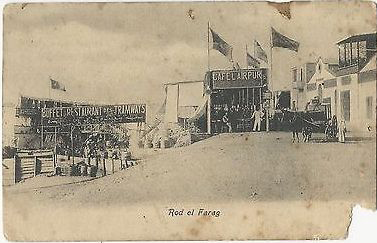

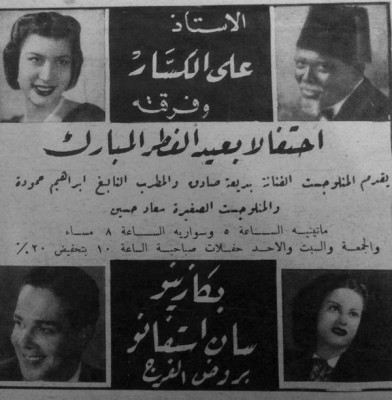

The period following the end of the war witnessed the rise of Rawḍ al-Farag as an area famous for art and recreation frequented by Egyptians seeking entertainment away from the pretentious and expensive theatres in ʿImād al-Dīn Street and al-Azbakīyya in the town centre. It was also a place which British soldiers frequented for evening entertainment. This trend started when a Greek party-organiser decided to copy the old open-air theatres common in Greek and Roman times as an alternative to town centre theatres, which were not well attended during summer months due to their poor ventilation and enclosed spaces. Therefore, to try his luck he rented a vacant plot by the Nile in Rawḍ al-Farag. The Nile bank in Rawḍ al-Farag was the summer resort for Cairenes at the time and they named it ‘Rawḍat al-ʿUshāq’ [the garden of lovers]. He furnished this plot with a stage and seating for the audience. He devoted a corner for a buffet selling sandwiches and soft drinks to the clientele and theatre goers – referred to as ‘Marsaḥ’ in the vernacular of the time. To begin with, many considered this venture rather unusual. Indeed it was criticised by the owners of well-known theatre companies at the time such as Shaykh Salāma Ḥigāzī who rejected it claiming that such open spaces, where there was no ceiling above the actor’s head, prevented him from perfecting his part! The Greek entrepreneur had no alternative but to approach a young unknown actor called Nagīb Afandī al-Rīḥānī, who agreed to hire the theatre from him. The idea succeeded and encouraged others to emulate the Greek Khawāga [foreigner]. Therefore, in the space of only two years, eight open-air summer theatres were in operation on the banks of the Nile at Rawḍ al-Farag.14 These were an amalgam of cafes and nightclubs or casinos and theatres. These theatres – San Stefano, Park Miramar, Monte Carlo, and Lila’s15 – were mostly owned by Greeks or Europeans as demonstrated by their names such as Yani, Christo and Anton. They operated daily from 7 o’clock in the evening until 11 pm to take account of the last tram service in the area which came from al-Sakākīnī and arrived at Rawḍ al-Farag at 11 pm.16

A few of the Rawḍ al-Farag Nightclubs which operated as cafes and theatres simultaneously, as recorded in this postcard (source)

As Cinemas were not prevalent then, the theatres of Rawḍ al-Farag were the venue for recreation and celebration, particularly during events such as the Eid Al-Fitr (Source)

These theatres represented the golden age of art during the early part of the last century and launched the careers of some of the most famous classical artists such as Nagīb Afandī al-Rīḥānī, ʿAlī al-Kassār, Fāṭima Rushdī – who was considered ‘the East’s Sarah Bernhardt’, Shukūkū, Ismaʿīl Yāsīn, Āmīna Rizq, Marī Mūnīb, and many others. These theatres continued to flourish until the inauguration of the Egyptian Radio Service in 1934 which started to broadcast old plays. With the gradual spread of radio sets in cafes and homes, the population was content to listen to these plays on the radio and therefore the glory days of Rawḍ al-Farag began to gradually wane. By 1955, most of the theatres were demolished as part of a project to widen and pave the Cornish, while others simply crumbled into deserted wastelands.17

But Rawḍ al-Farag’s importance was not only due to its reputation as a venue for recreation and entertainment. During the first half of the last century, al-Sāḥil area was a primary source of livelihood in Cairo, as it was a port for ships, steamboats, barges and boats. These ships came from a variety of places arriving at al-Sāḥil via the Nile, loaded with grains and seeds from Upper Egypt, rice from Damietta, and sardines from Rosetta. All these products were for sale in the public al-Sāḥil market. Nothing remains as a witness to these days, charged as they were with vitality and plenty, except for some grain stores and warehouses in al-Sāḥil Market and Dhu al-Faqqār Street which continues to be frequented by large barges from Upper Egypt laden with wheat, beans and corn, and Sūq al-Balaḥ, which is famous in the area particularly during the month of Ramadan. Even the Rawḍ al-Farag market which was built in 1947 and which had become the central fruit and vegetable market serving Cairo was moved to Madīnat al-ʿUbur in 1994 and its building was turned into Rawḍ al-Farag Culture Palace. The presence of this market was the primary factor motivating farmers and peasants to settle in the area in the middle of the twentieth century when they left their villages in search of a more comfortable livelihood.

Postcards showing scenes from Rawḍ al-Farag at the beginning of the last century: the Nile port and the grain market and as a place of commercial plenty where produce from the various areas of Egypt was exchanged and sold

Following the July revolution, the area was subsumed under the grand plan for the development of Cairo by ʿAbd al-Laṭīf al-Baghdādy – Minister for Municipal and Rural Affairs, who widened Shubrā Street to 40 meters, and moved the tramline to the centre of the street. He also extended the Bulāqīyya Canal Street up to Shubrā Street after having filled in what remained of the canal. He erected a subsidiary bus terminal for the Delta bus line coming from Cairo.18 During the second half of the twentieth century, Shubrā witnessed a big increase in population due to internal migration from the countryside so much so that the population doubled to 300,000 by 1987.19

However, over the next three decades this increase steadily slowed down and the rate of migration from the countryside also declined. Indeed Shubrā experienced a net reduction in population, during the latter part of this period. However, this historical district continues to be heavily populated and remains one of the most densely populated areas in Cairo. In stark contrast to the peaceful recreation-ground frequented by princes and dignitaries that it once was it has now become one of the noisiest and most diverse areas in the capital.

The Place and Its People

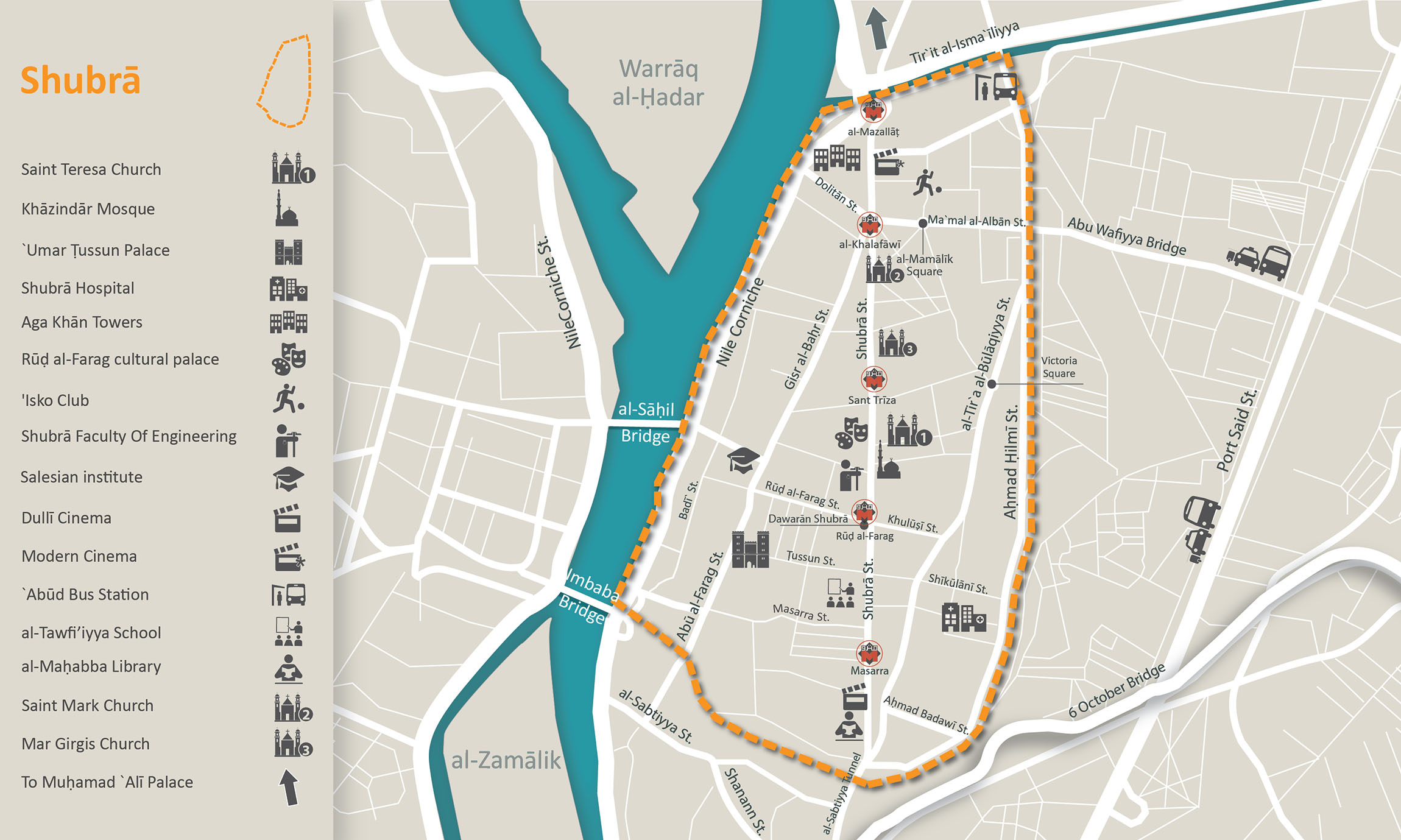

The administrative divisions between Shubrā, Rawḍ al-Farag and al-Sāḥil follow the main thoroughfares of Shubrā Street, Rawḍ al-Farag Street and al-Khulūṣī Street

Shubrā did not become part of the Cairo administrative unit until the mid-1950s following the 1952 revolution. With the extensive urban expansion in Shubrā there was a need to establish administrative boundaries. Today Shubrā falls under two of the greater Cairo governorates. The area from Āḥmad Ḥilmī Square until al-Miẓalāt Square north of Cairo comes under the Cairo Governorate, this includes the areas known as Shubrā Maṣr, Shubrā al-Maẓalāt, Rawḍ al-Farag and al-Sāḥil. The remaining area from Al-Mu’assasa Square known as Shubrā Al-Khayma now comes under the Qalūbīyya Governorate. Shubrā is bordered by the districts of Sharābīyya to the east and Būlāq and Azbakīyya to the south. Shubrā’s administrative borders follow its physical borders as the Nile and the Ismaʿīlīyya Canal constitute the west and north perimeters, while it is bordered by the northbound railway line to the east and south.

Because the Nile, canal, and railway line are part of Shubrā’s boundary, bridges play a vital role in connecting it to the city. There is Imbāba Bridge which connects Rawḍ al-Farag to Imbāba in Giza – which is one of the oldest bridges in modern Cairo, al-Sāḥil Bridge which connects Imbāba and Warrāq to Giza and Sabtīyya Bridge with Būlāq Abu al-ʿIlā and al-Miẓalāt Bridge to Shubrā al-Khayma in Qalubiyyia. The internal borders of Shubrā, Rawḍ al-Farag and al-Sāḥil follow the main thoroughfares of Shubrā Street, Rawḍ al-Farag and al-Khulūṣī.

Despite the commercial character of some of these streets, particularly al-Khulūṣī Street which is permanently congested because of the large number of shops, Shubrā remains by and large a residential area, reflecting up to this day the original character of its early residents. An area such as Rawḍ al-Farag, which received the first wave of internal emigrants who came from the Būlāq area in the 19th century, continues to be characterised by poorer socio-economic levels similar in character to the nearby Būlāq district. Moreover, during the past decades there appeared a number of informal settlements although the vast majority of these occurred in al-Sāḥil area, which received most of the successive waves of migrants during the mid-twentieth century. Rawḍ al-Farag and al-Sāḥil are more densely built-up than Shubrā with buildings amassed close together. In both these areas there are higher incidences of illegal construction. In general, the prevailing character of the buildings together with their workmanship gradually decline the further one moves away from Ramses, where styles and types of building become more diversified suggesting a natural or spontaneous development particularly around the peripheries. Nevertheless, Shubrā exhibits more formal urban planning when compared to other areas of Cairo.

From the first glance one perceives Shubrā Street as being the basis of the area’s urban plan. From this street radiate out other streets leading to other parallel or intersecting streets. The second route of the Metro passes under Shubrā Street where there are five underground stations dotted along the length of Shubrā Street. This street, which begins from al-Qullaly in the south, to Al-Miẓalāt in the north, is considered one of the longest and most significant commercial streets in Cairo. It is a thriving commercial street particularly around the area of the Shubrā Roundabout which competes with the downtown Cairo and is visited by shoppers from all over the city. Stores, such as Asmāk al-Amīr [al-Amīr’s Fish], Shirbīnī Stores, ʿUmar Afandyī and al-Tawḥid Wa al-Nur department stores, are well-known and prosperous. There are also large numbers of street vendors along the pavements. When the second Metro line opened, famous restaurants opened branches there to capitalize the popularity of the area. These included Mo’min, Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC), McDonalds and the pastry shops of ‘La Reine’ and ‘Qaṣr al-Ilīzīh’. Consequently prices of commercial properties steadily increased until they reached half a million Egyptian pounds for a small shop of no more than 10 square metres and five million Egyptian pounds in areas close to al-Masarra station, Rawḍ al-Farag, and Saint Therese. At present there are two cinemas on Shubrā Street – one at the beginning of the street called Dolly (which was subsequently renamed Farīd Shawqī), and the second towards al-Miẓalāt called Cinema Modern, which is part of the shopping mall.20 Shubrā was once full of cinemas such as al-Amīrr open-air cinema on al-Khulūṣī Street, the famous ‘Shubrā Palace’ on al-Tiraʿa Al-Būlāqīyya Street – which was demolished and replaced by high rise apartments and likewise with ‘al-Gundūl’ and ‘al-Nuzha’ cinemas. In general this was the fate of most cinemas in Shubrā as there is now only one famous second class cinema in Shubrā left which is ‘Dolly’ cinema.

Āḥmad Ḥilmy Street runs parallel to Shubrā Street and is a major route through the area and a primary thoroughfare linking Cairo and the governorates of the Delta. The Āḥmad Ḥilmy terminal next to the railway station was one of the most important for taxis and Delta buses until recently when it was relocated to ʿAbūd.

The three thoroughfares: Shubrā Street, Āḥmad Ḥilmy Street and Būlāqīyya Canal Street bisect Shubrā lengthways. Between these longitudinal streets there is an extensive network of streets crisscrossing it, the most famous being al-Khulūṣī Street which connects the Būlāqīyya Canal Street and Shubrā. This street is considered to be the most important commercial street in the area. Āhmad Badawy Street connects Āḥmad Ḥilmy Street, the Būlāqīyya Canal Street and Shubrā. The Būlāqīyya Canal Street is famous for the numerous car accessory and spare part dealers and the most recently-built square in Shubrā – Victoria Square – is situated there. From Victoria Square, two streets well-known to all Cairenes branch out: al-ʿAṭār and al-ʿAsāl (they are two of the streets mentioned in Shaʿban ʿAbd al-Riḥim’s song) and ‘Chicolani’ and ‘al-Maḥmudī’.

Shubrā Street is the oldest street in Shubrā and Gizīrat Badrān is the oldest area in Shubrā. Unfortunately, the palaces and villas which distinguished this area in bygone days have now been demolished to be replaced by urban developments and high-rise apartment buildings. The Gizīrat Badrān area forms the border of Shubrā with the historic Būlāq area towards the Mazlaqān al-Nigīlī, which overlooks Sabtīyya Street, where the southbound railway line divides the two historic districts as it passes over the Imbāba Bridge.

Al-Khalafāwī and Ard Agha Khan are among the modern additions to Shubrā and they are where wealthier residents choose to live. Agha Khan overlooks the Nile on the al-Miẓalāt side. al-Khalafāwī is directly connected to other neighbouring areas of Shubrā such as al-Shaykh Ramadān and Victoria via well-known roads such as ʿAbd al-Ḥamid al-Dīb and Muḥammad al-Khalafāwī. The latter was named after one of the great Azhar scholars who opposed Khedive Tawfīq during the ʿUrabī revolution at the end of the 19th century; one of the main underground stations is situated there. There is a clear Azhar flavour to this area evident in street names in al-Khalafāwīas many of them are named after Azhar scholars such as Muḥammad al-Ẓawahry, ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Qurāʿ, ʿ Abd al-Laṭif al-Faḥām, ʿAbd al-Karīm Sulimān, and others. Some streets are also named after Islamic historical figures such as: Ibn Taymiyya Street, Sayyida Khadīga Street and ʿUmar Ibn al-Khaṭāb Street.21

Turning to street names in Shubrā, we will find that they continue to commemorate the historic founders and original innovators of the area. Street names such as al-Bāshā (clearly referring to Muḥammad ʿAli Bāshā), Ḥalim Bāshā Street (one of Muḥammad ʿAli’s sons who inherited Shubrā Palace), Rifaʿat Street (Son of Ibrāhim Bāshā and grandson of Muḥammad ʿAli) and Sʿaīd Bāshā (the third ruler of Egypt of the Muḥammad ʿAli dynasty). The journalist, ʿAbbās al-Ṭarābīlī, gives an account in his book about the districts of Egypt and their history, and how the 1952 Egyptian revolution changed street names bearing the names of members of the Muḥammad ʿAli dynasty. This was part of the revolution’s pursuit of everything that bore any relationship to the monarchy in an attempt to obliterate their connections to the history of the area.22 Equally we could consider both Āḥmad Ḥilmy and Victoria among the pioneer innovators of the urban development of Shubrā, whose names were retained for two of its most famous streets and squares.

Āḥmad Ḥilmy, after whom the street and terminal are named, was not merely one of the genuine patriotic activists prior to the British Occupation in his role as a comrade in arms to Muṣaṭafa Kāmal for seven years. There was a time when this angry journalist – he published articles attacking the Khedive’s family in al-Luwā’, al-Shab and al-ʿIlm newspapers – deserted his profession to work in agriculture. One of the advantages of his successful work in this area was his acquisition of a large tract of land in Shubrā where he built a large multi-story building towards the entrance of the district near the street which bore his name after his death in 1936. One of his grandsons was the journalist, poet, and caricaturist Salāḥ Jāhīn. It was said that both he and Balīgh Ḥamdy lived in the same building on Badīʿa Street in Rawḍ al-Farag. This street was named after Badīʿa Khairī who was famous as one of the pioneers of Egyptian theatre. He spent a significant part of his life in Rawḍ al-Farag at the time of its heyday as the theatre district. Thus, in a way, the streets retell the events and history of the not too distant past.

Street names also allow us to follow fundamental geographical changes that occurred in the area. The naming of al-Tirʿa al-Būlāqīyya Street (Būlāqīyya Canal Street) reflects the presence of an old canal that connected Būlāq Abu al-ʿAlā and Shubrā which is why it was named after the Būlāqīyya Canal. A section of this street still falls in the Būlāq area towards al-Sabtīyya and al-Qulalī. Before the canal was filled in, the al-ʿAsāl area which overlooked it was famous for the fertility of its soil. However, now it has become one of the poorer densely populated areas of Shubrā. The events of a well-known Egyptian film are set in this area (Bitter Day, Good Day – 1998) . Fātin Ḥamāma played the role of a poor lady living there with her family which had lost its breadwinner as she tries to earn a living in the midst of a series of hardships. The famous Maʿmal al-Albān Street – which had become a part of the circular road linking Shubrā to Nasr City via al-Zāwiyya al-Ḥamra and al-Ḥadā’iq – replaced a canal connecting the Nile to Āḥmad Ḥilmy Street, called al-Tīrro Canal.

Place names also reveal the effect of the diverse cultures in Shubrā, for example the Garbadian Land which is located opposite Shubrā Street in front of Agha Khan Towers was named after an Armenian who had an art studio there. There is also Victoria Square which was incorrectly believed to commemorate Queen Victoria’s historic visit to Egypt. In fact Victoria was a Greek lady who inherited a large tract of agricultural land from her father together with her sister. Contrary to her sister who refused to live in what was once a remote area, Victoria built a residential building which carries her name. She settled there in 1955 at a time when the rural character and remoteness of the area made living there somewhat adventurous. This lady laid down the foundation for the development of the area through building more residential rental properties. She established two petrol stations and a market which facilitated the construction of transport routes to the area and hence drawing more residents to it. To this lady is owed the greatest debt in starting the development of the area surrounding this square. Perhaps she could be considered, together with Āḥmad Ḥilmy and others, one of the original developers of the area.

Akin to the Armenian Garbadian and to the Greek Victoria, other names of foreign nationals who had settled in Shubrā have become equally famous. Dalida the well-known actress and singer was born in Shubrā and her original name was Yolanda Christina Gigliotti. She was descended from an Italian family which settled in Egypt at the beginning of the 20th century at a time when Egypt was a free country full of promise and opportunities. We gather from Dalida’s memories about her birth place (where she spent her younger years and through the map she draws of the geography of Shubrā at the time) how the area was a thoroughly cosmopolitan society. Foreigners (Khawāgāt – as termed by Egyptians) lived side by side in the same place with the locals where they had built schools, hospitals, and clubs, such as the Italian ‘Salesian’ school and the Greek club (which became known as ‘Isco Club’). This was a society that was reflected in novels such as Bint Shubrā [the daughter of Shubrā] by Fatḥy Ghanim (1986) which was set in the 1930s and was about an Italian girl living in Shubrā. There was also the novel Shubrā by Naʿaīm Ṣabry (2000) which was about the interwoven lives of Muslim, Christian and Jewish families with Greek, Armenian, Lebanese, and Palestinian extraction in the mid-twentieth century.

It is likely that this cosmopolitan spirit – if we can use this term – which prevailed until recently in Shubrā, perhaps until the beginnings of the 50s of the last century, produced this celebrated climate of coexistence between Muslims and Christians. This as a common denominator in a lot of literary and artistic works set in Shubrā such as the novel by Baha’ ʿAbd al-Magīd, Saint Therese (2002), the film “Film Hindi” (2003) or the television serial ’Shubrā’s Roundabout’ (2011). This spirit gains even more credibility when artists originally from Shubrā such as when Muḥarram Fuad, sang “I love you Shubrā” (listen to the song).

The effect of Shubrā on the Cairene perception is demonstrated by films, novels and works of art that reminiscence about it, refer to it or take place in it, either through its history or through its current reality.

If this religious and ethnic pluralism and diversity in Shubrā is facing a crisis of existence at present (as reflected by the residents’ difficulties and the marginalisation that the whole nation suffers from) it nevertheless appears in these drama productions as steadfast and deep-rooted. A good example is the symbolic ending of the film “Hassan and Marcos” (2008). Could one assume that this is the same in real life? The image of Shubrā as a model of coexistence, tolerance, and “national unity” in public discourse may have another side which is revealed in a “struggle for identity” – particularly the religious identity of the place. This is evident in a number of revealing incidents which cannot be overlooked– what happened in Victoria Square in 2009 serves as an example. At the time one of the philanthropic religious civil society organizations attempted to change the name of the square to “Naṣr al-Islām Square”. Indeed, a new signboard was put up displaying the new name and adding “previously named al-Tirʿa al-Būlāqīyya Street” in a deliberate attempt to obliterate the name Victoria completely from the history of the place. This event was widely discussed at the time particularly in view of the uproar caused by the lawsuit raised by one of the well-known Coptic lawyers stating that it was an attempt to “Islamize” Shubrā especially because it coincided with the renaming of a number of other streets in the area. For example, Ṭūssūn Street was renamed “Ibn Faḍal Allah al-ʿUmarī”23 As though the surge of the July 1952 revolution – as pointed out by ʿAbbās al-Ṭarābīlī – refuses to desist from pursuing the Muḥammad ʿAli Dynasty through the streets of Shubrā.

Conversely, what was termed as “Islamization of the streets” in Shubrā is now offset by what is being termed as the “Christianization of property”. A journalist in one of the opposition newspapers, al-Wafd, described this as “a phenomenon alien to our Egyptian society” and stated that she had observed it herself as a resident of the area from childhood. This is the phenomenon of “the eagerness of Christians to buy older properties from their Muslim owners at any price, then demolishing them and rebuilding them as high-rise towers to sell or rent all these flats to Christians only to the exclusion of Muslims. churches in Shubrā “which are very numerous” (quotation marks as used by the journalist) play an enigmatic role in the acquisition of the old properties from Muslims with high asking prices using funds of unknown origin.” 24

These phenomena occur in Egypt amidst a general atmosphere rife with contradictions. While public discourse celebrates Shubrā as a model of coexistence between the Egyptian Muslims and the Egyptian Christians, and is presented as the prevailing spirit throughout the land, we find that from time to time arguments in newspapers and on television flare up about the Coptic census and their percentage of the Egyptian population as a whole. Shubrā is often thrust into this ongoing dispute, by virtue of it being the largest concentration of Copts in Egypt, according to Archbishop Anba Pachomius. Archbishop Anba Pachomius recently stated this in his response to the unofficial declarations made by the Head of the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics regarding the number of Christians in Egypt.25 Since United Nations principles and international decrees prohibit conducting censuses based on religious affiliations on the grounds that this may cause unnecessary religious discrimination, the 1986 census was the last one conducted in Egypt containing public and accessible information about the distribution of the population on the basis of religion. It is more common now for censuses conducted by the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS) to include an “optional” question about religious affiliation but citizens are not obliged to provide answers to it. Currently, CAPMAS’s public position is that it does not hold sufficient information about the numbers of Copts or Muslims.

This higher concentration of Copts in Shubrā when compared to the rest of Cairo is not due to a specific historical event. The explanation offered by Dr. Muḥammad ʿAfīfī, Professor of Modern History at Cairo University and a long time resident of Shubrā, is that Copts moved from the Christian quarter, which was the prevailing system in Egypt prior to second half of the 19th century to modern residential areas, such as Shubrā.

The Christian quarter was the prevailing system for residential areas in the pre-modern era in the East where members practicing the same crafts or occupations tended to live in close proximity to their workshops and occupational centres. Members of the same tribes tended to live in alleys specific to their tribe and similarly members of religious communities were attracted to living close to their main places of worship. In this respect, the presence of the Christian quarter is no different to the presence of areas for tentmakers, spice dealers and the Rum Alley etc. The Christian quarters were widely known during the Ottoman period both outside and within Cairo. In the 18th century the main concentration of Copts was in the Christian quarter close to the Azbakīyya Lake where the papal seat was at the time (before it was relocated to the present site in ʿAbāsīyya). Therefore, “the current concentration of Copts in residential areas such as al-Fagāla, al-Qulalī, al-Dhāhir and Shubrā is but a normal progression to the concentration in existence around the Christian quarter in Azbakīyya in the 18th century close to the old Cathedral.”26 However, the presence of Copts in Azbakīyya was not only due to the Cathedral, as Azbakīyya at the time was the primary port for Meks – i.e. duties and taxes. The type of professions Copts engaged in made it essential for them to reside close to the port. We find that with the modernization of Cairo, the Azbakīyya area, during the reign of Khedive Ismaʿīl, was converted to a central park for the city along the lines of the Parisian gardens. Houses to the north of the lake, where the Copts lived, gradually disappeared to be replaced by modern European-style buildings. While the Nile ports in Būlāq and the Rawḍ al-Farag coast started to come to life, we find that it was only natural due to these changes that the Azbakīyya Copts employed in these fields should be drawn to settle there. This was in addition to those employed in the railway and postal services, particularly Copts, as well as migrants from the countryside and Upper Egypt looking for factory work. It is possible that the concurrence of all these factors and events paved the way for the historical concentration of the Copts in Shubrā.

In any case, it would not be appropriate to consider Shubrā a Christian area, or to view it as a city ghetto, where a particular religious group is isolated, since Egyptian Muslims and Christians have always lived side by side and interacted in Shubrā. Perhaps this quality manifested itself with great clarity, both symbolically and in reality, during the events of the 25th January and thereafter. Shubrā Roundabout for example became an assembly point for marches and demonstrations since the first day of the revolution. Shubrā Ḥilm Bokra [Tomorrow’s Dream], is the name chosen by Shubrā’s Popular Committee which was formed there to address the security vacuum that followed the 25th January revolution similar to other areas of Egypt. Although its members had decided that the committee should continue to offer services and to raise awareness after the revolution – their Facebook page continues to display a picture of a wall graffiti in the Shubrā Tunnel which records some of the names of martyrs in the Maspero massacre together with their portraits: ʿIsa Ibrāhim, Michael Musʿad, Muḥammad Gamāl al-Din, Āyman Ṣābir, Hādī Fū’ād, Shaḥḥāt Thābit, Romāny Makāry, Magdī Fahīm, Fāris Rizq and Mīna Daniel.

What Is Important in Shubrā

Shubrā’s location has been its main distinguishing feature since its foundation. Historically, it was difficult for Cairo to expand beyond the Nile or the Muqaṭtam hill, therefore expansion was always going to be to the north. This continued until Khedive Ismʿīl commenced his substantial modernization of Egypt. Therefore, the essence of Shubrā’s development has always been closely associated with its location. Its urban fabric tells many stories about past eras, industrialization, urbanization, and migration.

However, the most important story of all is the story which describes the coexistence, respect and trust between Muslims and Christians in Shubrā. Shubrā is considered a demographically mixed society where this demographic diversity did not lead to the segregation of the religious groups from one another in order to live in comfortable and easy uniform urban pockets as has happened elsewhere in the city. In most Cairo districts and in Egypt in general Muslims and Christians maintain social contact with each other but are careful to have separate religious lives from each other. It is true that Muslims share with their Christian acquaintances their social and religious events in their churches and vice versa, nevertheless on normal days they will not visit each other’s places of worship. This is different in Shubrā where we could find two places of worship such as Saint Therese’s church and the Khāzindāra mosque side by side only separated by a short distance on Shubrā Street being frequented by both Muslims and Christians!

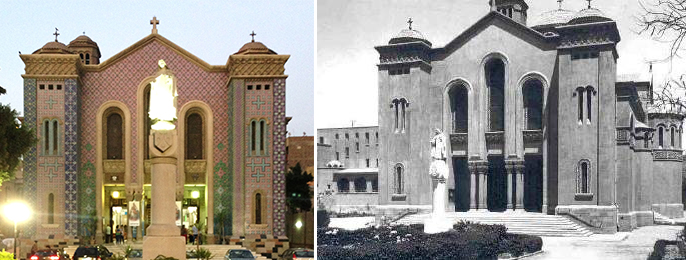

The Church of Saint Therese

The church of Saint Therese was built in 1931 and it was one of the first churches built in Shubrā following the migration of the Copts from Azbakīyya in the 1920s. It now stands among the residential buildings with a multi-coloured façade greeting the passers-by along Shubrā Street. Amid the bustle and noise outside, one finds a pleasing degree of privacy and tranquillity. As soon as you enter you encounter marble panels inscribed with the names of those who have fulfilled their pledges, Muslims and Christians, ordinary people, celebrities and intellectuals. Foremost among them you will find the name of ʿAbd al-Ḥalim Ḥāfiz on three panels for three separate pledges, as well as Farid al-Āṭrash, Ismahān, the musician Muḥammad ʿAbd al-Wahāb and the famous singer Um al-Kalthūm. In the nave of this Catholic Church you can see engraved on the back wall the Quranic verse “This is by the Grace of my Lord”, for all to see. However, Saint Therese does not only offer a spiritual refuge or the hope of answered prayers, it also plays a societal role serving all the Shubrā residents without discrimination. The church makes its theatre available to the community to use in their gatherings, school pupils are able to use it for their activities and presentations, as well as societies set up to assist widows and orphans such al-Salām Society, which is tasked with the disbursement of EGP 4 million per month in association with the Ministry for Social Solidarity.27

Al Khāzindāra Mosque

The al-Khāzindāra mosque was built four years before Saint Therese’s church. It is believed that Princess Khadiga Hānim daughter of Muḥammad Rāghib Āghā had commissioned its building. Her intention was that it should host the Muslims in their prayers, particularly the Friday prayer so she established the mosque together with a sabil (public water fountain) and a religious school to serve the residents of Shubrā. However, there are numerous conjectures around the mosque, one of them suggests that it was founded by a lady called Zainab al-Khāzindār, who was a Mamluk, and who had decided to build this mosque when she adopted Islam to be closer to God. Evidently, in 1927 when the mosque was built there were no Mamluks in Egypt. However, perhaps such theories gave rise to the mystery around the female gender of the name of the mosque, once in addition and once in omission as it is sometimes referred to as “al-Khāzindār” and sometimes as “al-Khāzindāra”. Externally, the mosque has dusty, worn-out walls and a huge dome with both walls and dome made of stone. The columns are of marble that was specially imported from Italy. The mosque covers around 600 square metres. When al-Azhar University was first being established, the attached school was selected to house one of the three initial colleges – which was the College of Islamic Theology, opened in 1931. With the beginning of the 25th January revolution and in view of the mosque’s ability to accommodate large numbers and its central location in the middle of Shubrā Street, Al-Khāzindāra mosque became an assembly point for both the revolutionaries and others such as the Ultras group.28

With respect to the Shubrā residents, there is a further reason that makes them value Al-Khāzindāra mosque which is that Shaykh Muḥammad Sʿaid Nur – an Egyptian reader of Sudanese origin – used to recite the Quran in this mosque during the 1930s. Shaykh Sʿaid Nur – who lived in Shubrā for a large part of his life – was distinguished from other readers of the Quran with his unparalleled recitation. His devotees believed that his method of recitation was the original and approved one. Despite the fact that he had a strong stance against making recordings for the Egyptian broadcasting service, contrary to other readers, his fame surpassed some of them. The secret was his remarkable recitation which drew the audience’s hearts and which was described as a mix of rapture and reverence leading them sometimes to weep. It is said that tram drivers passing by the mosque on Shubrā Street when Shaykh Sʿaid Nūr was reciting stopped the tram to listen to his recitation together with their passengers.

There is still a large number of churches and mosques in Shubrā. Of the mosques there are al-Fatiḥ in al-Khalafāwī, Bad ī ʿa in Rawḍ al-Farag and Naṣr al-Islām in Victoria Square. Of the churches, there is the church of Saint Mary in Masarra – which was the first church to be erected in Shubrā and the church of Saint Mark in Minyat al-Sirg which overlooks Shubrā Street and is the largest church in the area. The church of Saint George in Chicolani and the church of the Angel in Ṭussun both have large and significant theatres. However, it is clear that Shubrā does not only contain places of worship. Its architecture is varied even though it may seem at first sight that it is an ordinary residential area as described by Abu-Lughod who stated that Shubrā was “a solid mass of high rise residential buildings” lacking “a distinctive style.”29 The fact of the matter is that Shubrā in reality contains a number of distinctive buildings which represent different aspects of Cairo’s history with its various residents in all their diversity.

Muḥammad ʿAli’s Palace

Despite the fact that Muḥammad ʿAli’s palace actually falls within the administrative jurisdiction of Shubrā al-Khayma, which is beyond the geographical scope of this article, its vital role in Shubrā’s history – as previously demonstrated – necessitates its inclusion.

It appears that Muḥammad ʿAli’s ambition in building Shubrā palace was to establish a seat of government along the lines of the Topkapi palace in Istanbul, the seat of the Ottoman rulers. The extended area and the pastoral surroundings inspired its architect, Dhu al-Faqār Katkhudā, to build a garden palace in a style prevalent at the time in Turkey along the coasts of the Bosphorus, the Dardanelle, and the Sea of Marmara in particular. Central to this design is a large garden with a variety of buildings dotted around it. The buildings had a unique architectural style and both garden and buildings were enclosed within high retaining walls interrupted by a number of gates. This was a new style not previously seen in Egypt and therefore, thanks to this palace, Shubrā became the first place in Egypt to have ‘park architecture’. This predated the Montazah Palace built by Khedive Ismaʿīl in Alexandria.

During its heyday the palace appeared like “a bright pearl dispersing the darkness of the night” as described by Gérard de Nerval, who no doubt was taken by the brightness of its gas illumination, particularly at night.30 The palace and surrounding gardens were early contributors to the modernization of Egypt due to the introduction of a lighting system. Muḥammad ʿAli invited a British Engineer specially to connect the palace with a gas lighting system. This was the most recent innovation at the time. The palace was opened in 1829 and allowed Egypt to witness a civilizational quantum leap. Muḥammad ʿAli, who had previously opened the door for students to travel to Europe for further education, allowed agricultural college students upon their return to apply the new skills they had learned and to experiment with new plant varieties they had brought back that may be suitable for cultivation in Egyptian soil. This was the first introduction of modern crops and methods to be used alongside the traditional crops and methods prevalent in Egypt for thousands of years. It is worth mentioning here the tangerine [al-Yusfī] which was the fruit first introduced by one of these students who was named Yusuf Afandī. When he presented it to Muḥammad ʿAli he liked it so much that he ordered its cultivation in his palace garden in Shubrā. It was therefore a logical step to move the Agricultural College formally to the palace in 1833, followed by the Veterinary College in 1837. Therefore the palace was not merely the residence of Muḥammad ʿAli’s Harem as quoted in some sources nor was it just the countryside residence of the ruler of Egypt. It was transformed in the space of a few years to a centre for research and education and a basis for the modernization of the agricultural sector in Egypt and one of the country’s first modernist sites.31

Today nothing remains of this great palace except for three structures. The Water Wheel Tower which was part of the system providing the palace with water is the oldest of the remaining building having been built in 1811. The second structure is the Fountain Pavilion which was designed by the French Consul General – Monsieur Duravitty and executed in 1821 by the French Architect Pascal Coste, under the supervision of an Armenian Architect named Youssef Hakikian who was a member of the Egyptian educational delegation to England. This palace is unique in its internal design which features a large water pool and fountain as a focal point. This is surrounded by a gallery with domes decorated with motifs and images. The third structure is the Gabalāya Palace which was added in 1836.

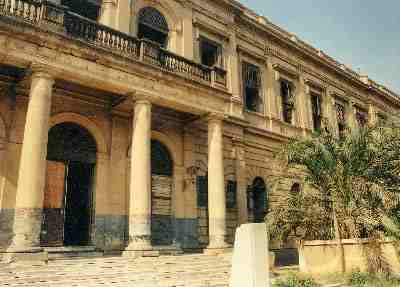

The Palace of ʿUmar Ṭūssūn

The palace which remains standing in the Rawḍ al-Farag area, despite the changes and the fate that has befallen it, continues to inspire us to imagine its heyday and glory through its regal design, at a time when Shubrā was an aristocratic area inhabited by the country’s dignitaries and distinguished foreign residents. It is one of three palaces belonging to Prince Muḥammad Ṭūssūn – Muḥammad ʿAli’s grandson, which were then inherited by his son ʿUmar Ṭūssūn. It was built in 1880 and is one of the most important historical buildings in Shubrā. Sadly, following the 1952 revolution it was used for a time as a secondary school before the nation became aware of its artistic and historical importance and took steps to have it listed as a heritage site in 1984. This was followed by a period of neglect when there was a fire that consumed most of the contents of the second and third floors. A number of modern buildings have now encroached on its gardens which once were very spacious. It is a bitter irony that all this happened following the government’s formal recognition of its historical value. The residents of Shubrā who have always felt passionate about the heritage of their area, expressed their concern regarding the condition of the palace and lately the Ministry of Antiquities announced its plans to convert it into a museum for cinematic history.32

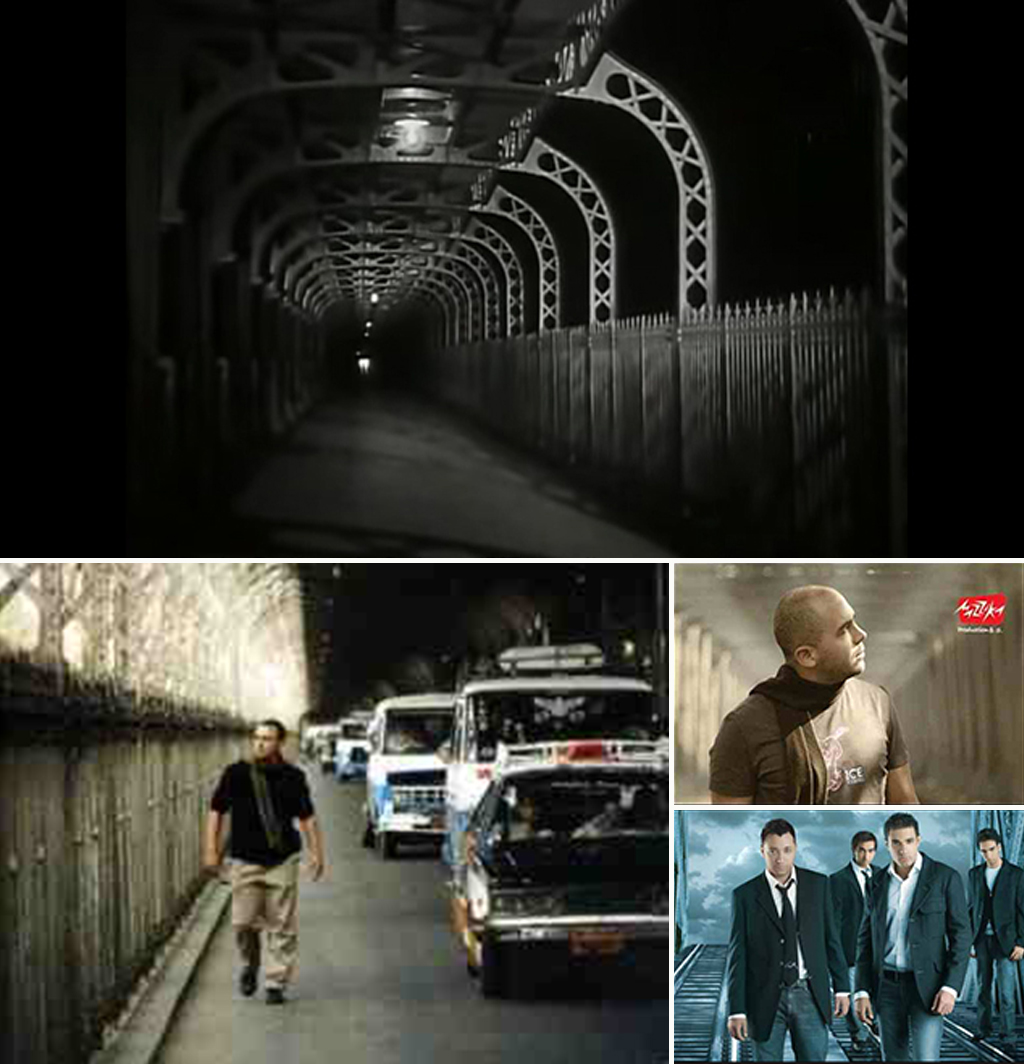

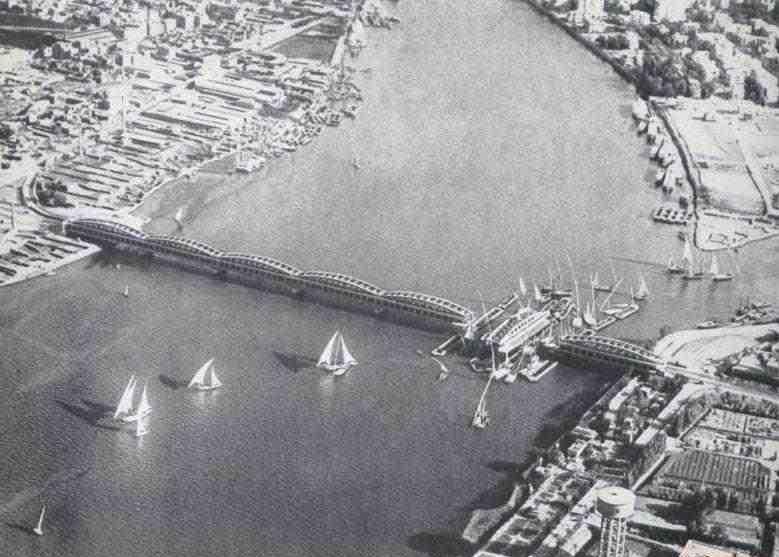

The Imbāba Bridge

The Imbāba Bridge in particular has a remarkable history. The present-day bridge was erected in 1925 and overlooks three districts, al-Zamālik, Shubrā and Giza. However, this was not the first bridge to be erected on this spot as there was a previous bridge built in 1890, the construction of which was overseen by a French engineer called David Trombley. This bridge is now in Damietta and is known as the Damietta Bridge. It was relocated there after being replaced by the present one in Imbāba.33 The Imbāba Bridge is considered an engineering feat as its metal frame is on two levels and it has separate pathways for pedestrians, cars, and trains.

The bridge’s impressive role in Cairo’s urban life is demonstrated through its popularity as a film location and as a backdrop for artistic works. First there were the black and white films such as House No. 13 (1952), which is an Egyptian film whose events centre on a murder mystery. This was renowned director Kamāl al-Shaykh’s first film. Imbāba Bridge is the backdrop for the concluding scene between the lead actor and the killer – played by mād Ḥamdy and Maḥmud al-Miligy. More recently the director Ṭāriq al-ʿAryān chose Imbāba Bridge to be the backdrop for the poster of his film Tito (2004) showing the lead-actor Āḥmad al-Saqqā on the bridge. There are also a number of shots showing the bridge from a variety of angles. This interest is not limited to films alone as a number of young singers, particularly during the era when ‘song clips’ were enjoying increasing popularity, filmed their songs along the bridge (such as Ehāb Tawfīq). To this day the strong visual impact of the ancient bridge continues to be utilised as a background in album covers of famous young singers’ works.

Various shots and posters of old and new Egyptian movies and song albums of young singers shot on Imbāba Bridge

The Imbāba Bridge is not only an impressive visual element in the landscape of the city, but it is also a vibrant, thriving location closely connected to the lives of the people. It continues to inhabit its distinctive position in the popular consciousness. We sense this through the poetry of Fuād Ḥaddād where he describes this bridge and the life surrounding it through the character of the Misaḥḥarātī34:

Metal staircase in the water reflected in light

On Imbāba Bridge for seasons and seasons (…)

I happily worked as a fruit seller in the town

Peddling al- ʿAgamiya and sweets from Ḥulwān

Fragrant guavas and colourful grapes

Oranges, gentle breeze, tangerines and apricots.

I saw the bridge’s metal fluttering an eyelid tenderly

And my voice flew over the garden fence with the nightingale

And in the dew I praised Imbāba and the universe

Similar talk is now being touted about Imbāba Bridge reminding us of what happened to Abu al-ʿAlā Bridge, which connected Būlāq Abu al-ʿIlā with al-Zamālik. The Abu al-ʿIlā Bridge was dismantled and negligently stored, despite all the claims and suggestions being circulated proposing reassembling it and using it as a landmark in some cultural capacity or other. It remains piled as scrap metal and was exposed to rust, having been replaced by the cement 15th May Bridge in place of the historical legacy designed by Eiffel. This was described by the official al-Ahrām newspaper as ‘a massacre’ of historical bridges,35 in view of the artistry and splendour of these bridges which is completely lacking in the cement ones that are now proliferating everywhere in the city.

Besides the ‘crisis of existence’ faced by Imbāba Bridge, it is constantly robbed of its electricity cables and metal parts. In addition, it suffers from indiscriminate negligence, where users complain of poor lighting at night particularly in the section under the jurisdiction of the Cairo Governorate (whereas the section under the jurisdiction of the Giza Governorate is well lit – residents attribute this to reasons of national security!). Despite the fact that Imbāba Police station is just a few yards away from it, the Bridge is considered an unsafe area where people complain of the absence of security even during daylight hours. It is therefore hardly surprising that Shubrā residents consider Imbāba Bridge to be one of the worst spots in the area.

Rawḍ al-Farag Market (Currently Rawḍ al-Farag Palace of Culture)

Rawḍ al-Farag market might be the most famous area in Shubrā, if not for having been the main fruit and vegetable market for Cairo residents for a very long time, then because of the enormous uproar which occurred when it was relocated to Madīnat al-ʿUbur in 1994. Rawḍ al-Farag market was established in 1947 and was from the start designed to be the primary market for the capital. Indeed, by 1991 it was serving six million Cairo residents and alone provided the equivalent of 30% of the city’s supply of fruits and vegetables.36 Nonetheless the market which is situated in Gizīrat Badrān was not simply an area for buying and selling, but was what amounted to a commercial centre attracting thousands of traders and farmers looking for work opportunities in Cairo. It was one of the centres of accelerated growth for Shubrā in the mid-20th century. This eventually led to its relocation out of the area in view of the burden it placed on the building and the infrastructure of the area. This decision was met with anger and hostility from the residents and resulted in confrontations with the authorities leading to regrettable events including casualties and fatalities. This coloured the residents’ attitude towards the new use of the building as a palace of culture until recently. This hostility arose in particular because the authorities made no attempt to ease the situation by providing them with adequate means of transport after having displaced their source of livelihood far away from their homes. This led them to employ their own initiatives in establishing a community cooperative society in order to create a transport route from Rawḍ al-Farag to al-ʿUbur.

However, the traditional character of the market continues to be felt and is clearly visible in its external walls with their ochre colour and its main gate that continues to bear the name ‘Rawḍ al-Farag Market.’37 Perhaps this will remain as the only memory of the days of plenty, activity, the buying and selling, and the daily drama of the rise and fall in prices. For example, there was an article taken from an old edition of al-Muṣwir magazine recounting the events of a blood-stained fight between two of the big families in the market in 1947. Truncheons, rifles, and machine guns were used and led to causalities and fatalities. Such an atmosphere cannot be recreated in this place once more except through films such as “al-Fitiwwa” (1957) whose script was written by Ṣalāḥ Abu Sīf and Naguīb Maḥfuẓ. The story was inspired by the real-life relationship of one of the traders with the Royal Court prior to the July 1952 revolution. You could watch Farīd Shawqī, or Āhmad Zakī in the more recent full colour production, in the film called “Shādir al-Samak” (1986) – each of them in a struggle with the city represented by the dark underbelly of the market’s society. The story revolves around simple farmers moving to the city in search of work opportunities. Perhaps one can now understand the origin of the underlying hostility expressed in the opinions and comments of the residents regarding the palace and its activities. This compels us to re-appraise concepts that continue to be espoused by the government and the Ministry of Culture such as that of ‘Mass Culture’. In a press report published by one of the independent newspapers the place is described as deserted and in a regretful state internally, encircled externally with feelings of repressed anger over a source of livelihood that has been destroyed and a feud that has not healed with time.38 In the view of most of the residents of Shubrā, relocating Rawḍ al-Farag Market was not a rational or adequately thought-out decision. It came from the top without consultation with the people concerned. For almost a year there were gun fights, killings and kidnappings – as described by a resident – in opposition to this decision. Conversely, the Palace of Culture which replaced the market has not played an effective role in the lives of the residents until today. Its activities have been limited to applauding official achievements rather than benefitting the community. Following the 25th of January revolution, when the initiative ‘Shubrā Ḥilm Bokra’ started using the Palace of Culture, it was barred in 2013 from doing so along with other local initiatives “due to concerns about public security”.

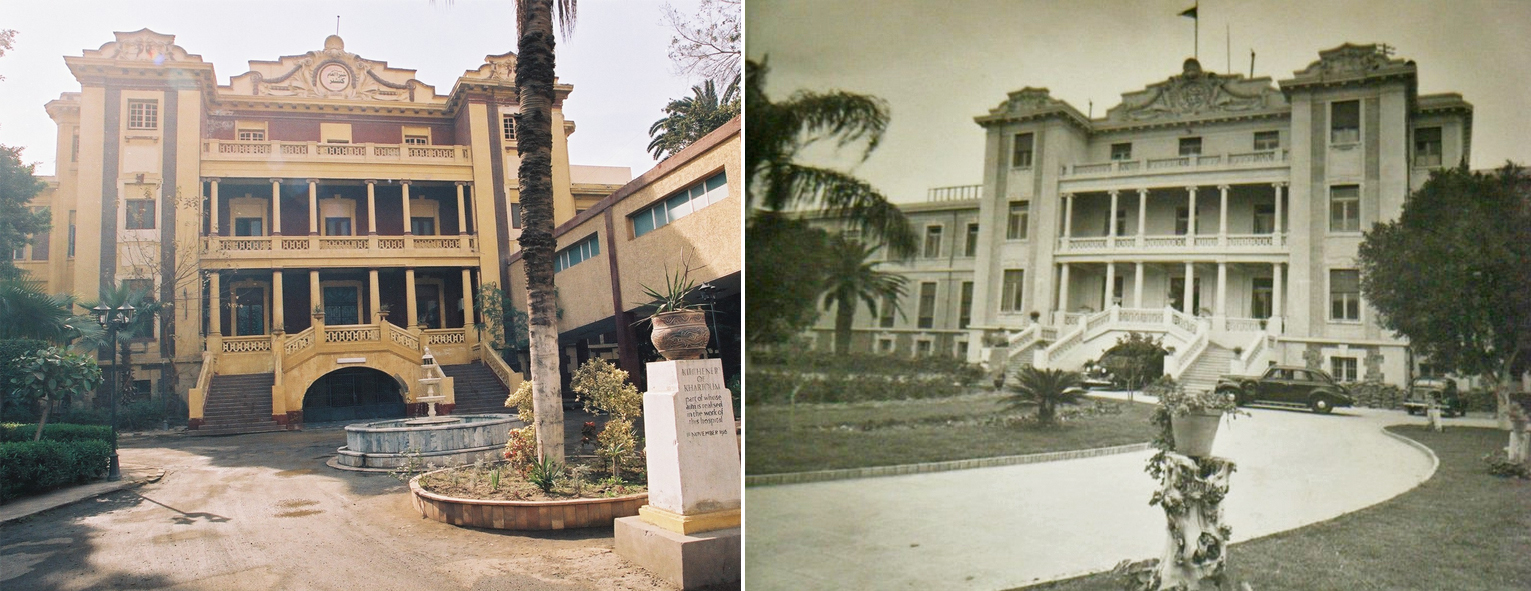

Kitchener Hospital

Some Shubrā residents believe that Kitchener’s Hospital – no one cares much for the current official name of ‘Shubrā General Hospital’ – was once the residence of Lord Kitchener, the British Secretary of State for War prior to the First World War. This goes against the history of the building which was established by the Austrian Prince Rudolph in 1881. It was designed by Maurice Qaṭawī and Edward Matsk (the same duo that also collaborated in designing the well-known Jewish Synagogue on ʿAdly Street in the town centre) as a hospital from the start to serve the Austro-Hungarian community in Egypt. In 1905 it was one of a total of 12 operational hospitals in Cairo.39 As the First World War proceeded, it was commandeered by the British Authority together with other buildings such as the Heliopolis Palace Hotel; a number of public buildings such as hospitals and hotels were commandeered in the service of the war effort in order to accommodate the wounded and war casualties. The building continues to bear the commemorative plaque referring to these events in English: “Kitchener – Khartoum/ The work in this hospital serves some of his aims/ 1 November 1916”. A British historian explains how this hospital became one of the largest hospitals specialising in infectious diseases and becoming with time the best hospital in this field in Egypt.40 41 By 1925 the ownership of the Austro-Hungarian Hospital transferred to one of the charitable organisations which acquired it and converted it into ‘Lord Kitchener’s Hospital for Women and Children’. Thus changing its area of speciality and its name by which it continues to be popularly known to this day despite the change of name to ‘Shubrā Hospital’ in 1954 when it came under the Ministry of General Health.

The fact is that Shubrā is packed with landmarks and important buildings. Shubrā residents themselves are most aware of the artistic and historical value of these buildings. There is, for example, Saʿid Pasha’s Palace which was erected by the fourth ruler of the Muḥammad ʿAli Dynasty in 1855 to be a rest house and a place for sport and recreation, which is situated on Shubrā Street. It was then used by Khedive Ismaʿīl for accommodating state guests and dignitaries. The Prince of Mecca al-Sharif ʿAbd Allah, for example, stayed there and admired it so much that upon his return he founded a district and a palace in the city of al-Ṭā’if which he called Shubrā to commemorate his stay in this palace in Egypt. This palace was converted to a secondary school when Khedive Tawfiq conceded its ownership to the Information Office in 1881 at which time it was renamed the Tawfīqīyya School. This school has produced some famous statesmen and scientist such as Abd al-Khāliq Tharwat Pasha, Muḥammad Maḥmud, Talʿat Ḥarb, artists such as Abd al-Wārith ʿAsar, ʿImād Ḥamdy and the historian Gamāl Ḥamdān. In connection with schools in Shubrā, there is also the Good Shepherd School which is one of the oldest and most important schools in the area on Shubrā Street. It is also a famous landmark together with its historic retaining wall. Shubrā residents are particularly proud of the quality of education in this school.

Shubrā’s landmarks are not limited to the era of the old monarchy. Shubrā’s urban development has continued hand in hand with the feverish building program that overtook all of Cairo in response to the severe housing crisis following the July revolution. The Agha Khan Towers were built on a site which was, until the 1970s, agricultural farmland and a burial-ground for wrecked cars. The area’s Corniche was empty except for a deserted palace, but with the construction of these tall luxurious towers overlooking the Nile at the beginning of the 1980s, urbanisation started to accelerate along it. This area – which Shubrā residents considered to be the most exclusive location in their area – was until recently where many of the affluent families bought apartments. Particularly so with Gulf Arabs who wished to have a base in Cairo. In spite of this now having come to an end, because most of these apartments are now owned by Egyptians, apartment prices remain exorbitant.

Should you wish to soak up the atmosphere of Shubrā – as opposed to merely getting to know the landmarks or streets and squares – you will find that Shubrā offers a unique urban experience. No one is better qualified than the residents themselves to tell you where to visit for recreation and shopping in Shubrā. Whether you are a Cairene or visitor, finding your way to Shubrā is easy due to its proximity to downtown and to its location at the entrance to Cairo. There is also the abundant availability of cheap community transport such as the microbus and the auto rickshaw (tuk-tuk) or via the metro which will transport you to the main Shubrā Street at one of the following stops: Masarra, Rawḍ al-Farag, Saint Therese, al-Khalafāwīor Al-Miẓalāt. There are regional terminals in ʿAbūd or the ‘Munūfīyyya Airport’ – which is the name given by the Shubrā residents to the Munūfīyyya bus terminal next to the Shubrā Telephone Exchange. People usually head to Shubrā to shop as Shubrā is nothing but a huge commercial mall, as stated by its residents. Most of the shops with their moderately priced goods, accessible to low-income families, are concentrated around Khulūṣī Street and the narrow Al-Ra’i Al-Saleh path which ends at the Tir’a Street. The most famous malls there are ‘Al-Ra’i Al-Salih’ and ‘Al-Amir’. If you get tired, you have access to the well-known Shubrā coffee shops with their friendly, warm atmosphere. As for those who wish to have a light snack on the way, they can choose from Western food chains such as Celantro, Kentucky or from their local equivalents: Gad and Koshari al-Tahrir. Or they can try Crepiano Restaurant on Chicolani Street – which the Shubrā residents boast – with excusable exaggeration – is the most important pancake shop in the Republic. As for Christian visitors they may wish to include in their tour of Shubrā a visit to Al-Mahabba Bookshop, which is of importance to all the Christians of Egypt. It is situated next to Al-Maṣarra metro station where there are a number of other bookshops most of which are Christian. Should you wish to conclude your visit to Shubrā with a pleasant walk, preferably by the Nile, the Shubrā residents will guide you to Dolitian Street in Agha Khan which terminates at the Corniche. It is a good street for walkers as the pavements are wide and it is nearly devoid of other traffic, but you will be advised not to remain there after dark as its seclusion may then become unsafe.

Shubrā’s Problems

The seventies and eighties of the last century were the most difficult period for Shubrā when overcrowding and congestion had reached their zenith. The mention of Shubrā to any Cairo taxi driver was sufficient to make him run away. Shubrā residents have suffered for decades with overcrowding and difficulties with transport until the nineties when the underground line was extended there. This was followed by redevelopments which included the removal of the old metro tracks from Shubrā Street. These steps contributed to the reduction of the congestion problems.42 Although it appears that problems faced by this ancient district never end.

The main feature of Shubrā is overcrowding. The crowdedness of the buildings increases as we move from Ramses to Shubrā Al-Khayma. While the density of the population in Cairo is around 45 thousand inhabitants per square kilometre, Shubrā occupies an advanced position among the heavily populated areas where the density of the three districts in question (Shubrā, al-Sāḥil and Rawḍ al-Farag) reaches 86 thousand inhabitants per square kilometre (as opposed to 83 thousand inhabitants in Al-Maṭariya District which is considered one of the most heavily populated in Cairo and 4,893 in Zamalek which has the lowest population density.)43 This is primarily due to the commercial nature that distinguishes the main streets of Shubrā, such as al-Khalafāwy, al-Khulūṣī and Shubrā Street itself and of course to the chronic housing shortage in Cairo.