Al-Darb al-Aḥmar Housing Rehabilitation Programme: Housing Rehabilitation beyond Physical Upgrading

The al-Darb al-Aḥmar Housing Rehabilitation Programme (HRP) has been initiated in 2000 by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC)1, in collaboration with the local government, and international donor agencies, as an effort aiming to build upon the completion of the Al-Azhar Park on the eastern edge of 12th Century Ayyubid city or Historic Cairo in 2004.2 The HRP is regarded by public authorities as well as international organizations as a best practice; the project was listed as such by the UN-Habitat in 2008. It is regarded by professionals and residents as an urban upgrading project that succeeded in stopping the downward spiral of disinvestment and deterioration in the neighborhood – one of the poorest in Cairo – while preserving the urban fabric and preventing the eviction of its dwellers. Hence, the project represents a move away from traditional approaches of monument conservation in Egypt to an approach that considers the area to be conserved as a whole.Combining published literature, internal documents and interviews conducted with architects engaged in the project, this article aims to provide an insiders’ view of the HRP, one that stresses not only its outcomes but also the challenges and shortcomings faced throughout the implementation process.

Situation of al-Darb al-Aḥmar before the Initiative

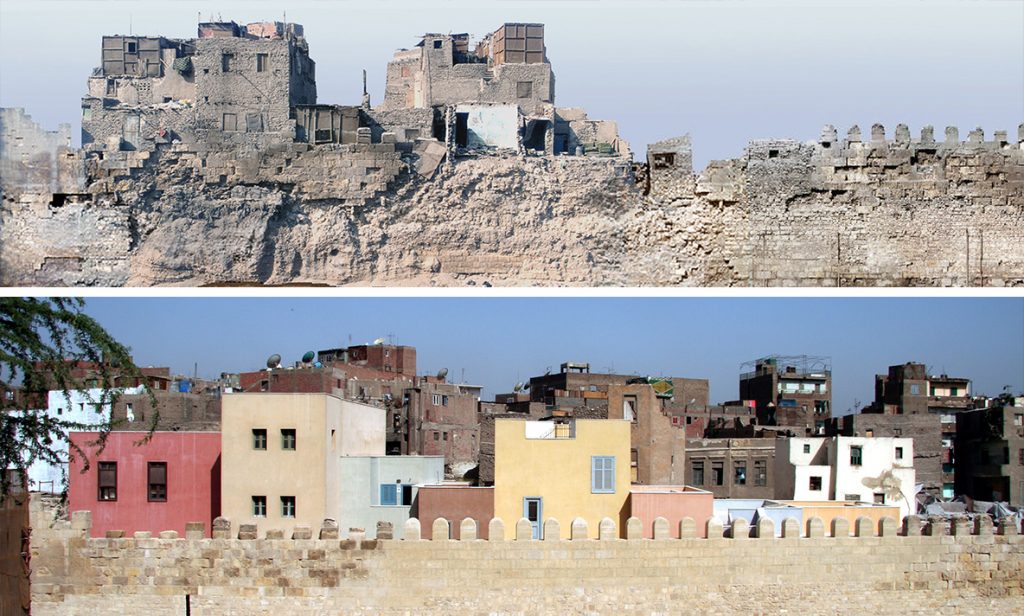

Less than two centuries ago, Al-Darb al-Aḥmar (ADAA) was one of the wealthiest neighborhoods in Cairo. It was and remains famous for its rich concentration of Islamic monuments.3 When the HRP started, the 100,000 inhabitants of this 1.2 km2 historic district were among the poorest in the city, with average income levels below EGP 500 per month in 2005 according to a survey conducted by AKTC. The area also suffered from lack of maintenance and infrastructure, as well as severe deterioration of monuments and housing stock.

In 2003, a baseline survey of ADAA revealed that on average 22% of the housing units had no private lavatory and had to share public toilets. Moreover, 51% of households were deprived of a consistent water source in their kitchens, while 32% of the dwellings had non-ventilated rooms. In the survey, over a third of residents (39%) complained of health-related issues such as poor eyesight, rheumatism, and chest diseases. In addition, residents reported a fear of building collapse – 27% complaining from its “deteriorated structural condition” (Shehayeb, 2003).

Living conditions in the neighborhood had been progressively deteriorating, as many residents were moving out of ADAA, which contributed to the loss of valuable social and economic assets. This loss is often misattributed to the 1992 earthquake, but according to national censuses, ADAA lost 50% of its residents between the mid 1970s and 1980s.

There are several factors that resulted in the ailing condition in ADAA. Outdated planning constraints are a first reason. Similar to many other deteriorating areas in the city’s core, the urban management institutional framework played a role in the area’s ailing condition. This not only limited the ability of residents to invest in housing in the area, but also local authorities’ investments. The 1973 Cairo master plan ignored the area’s historic fabric as major highways were planned to penetrate ADAA and some registered monuments were proposed to be demolished in the process. This proposal, was in clear contradiction with international conservation charters, such as the 1987 Washington Charter and the Australian 1999 Burra Charter, both developed by the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), that offer guidelines regarding the relationship between the conservation of monuments, public space and preserving the surrounding urban fabric, and address challenges that face conservation plans for sites – such as the ones in Egypt – that are in urban, densely populated areas. The 1973 master plan was ironically based on regulations introduced by the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA) – the 1983 Antiquities Protection Law – constructed to protect monuments. According to this law, existing monuments are to be surrounded by a buffer zone where all types of construction or development are prohibited. Surrounding urban fabric is allowed to collapse, leaving behind a vacant space, presumably protecting the monument. The complete implementation of this plan would have led to the demolition of significant stretches of ADAA’s urban fabric to “preserve” the adjacent Ayyubid Wall. Fortunately, this plan was never implemented. Yet, it caused a downward spiral of disinvestment and deterioration as ADAA inhabitants were not allowed to build or restore their houses (Ibrahim, 2011).

Second, 78% of the lease agreements of housing units in the neighborhood were subject to the Rent Control Law No. (136/1981), paying negligible rent – often less than EGP 10 per month (Shehayeb, 2003). As a result, property owners have limited financial benefit from their property and thus limited incentive to perform the required maintenance. In fact, in this case, as a property owner it is more profitable for the building to collapse and sell the land compared to collecting the meager rent. On another front, many tenants and owners didn’t perform the necessary maintenance and upkeep, due to financial limitations. The very low income of most residents in the neighborhood – tenants or owners – prevented them from having access to classic loans systems to repair and maintain their units and buildings. The results of the baseline survey conducted in 2003 showed that the average income level in ADAA was approximately 17 times lower than the national average (Shehayeb, 2003).

The Beginning of the HRP and its Development

From the onset, it was recognized that the Al-Azhar Park project could not be isolated from other development initiatives in the neighboring community of ADAA, such as the social and economic projects, as well as the rehabilitation of a number of historical monuments and buildings. As such, the HRP was one of the five programs – namely, housing rehabilitation, infrastructure and open space, employment, social services, and microcredit – launched in 1998 with the aim to reverse this deterioration process and improve living conditions in the ADAA while preserving the district’s historical character. Considering that physical upgrading interventions are only one aspect of the solution, the core element of the HRP was not only to rehabilitate a certain number of houses but also to create an institutional framework that supports the ADAA community on the technical, financial, legal, and administrative levels.

The HRP aimed to:

- Revise the institutional mechanisms to bridge the gap between legislative policies and residents’ needs (legal support);

- Facilitate residents’ access to housing grants and affordable loans (financial support);

- Improve security of tenure through resolution of legal conflicts between owners, tenants, and institutional organizations (technical support); and

- Promote higher conservation and building standards through advice, training, and monitoring of construction activities in the area (administrative support).

Project Implementation

The AKTC and its subsidiary in Egypt, the Aga Khan Cultural Services Egypt (AKCS-E), developed their rehabilitation strategy based on an in-depth study of the neighborhood and its households’ features. As a result, during the first years of the project, a bottom-up methodology prevailed. Inquiries included a qualitative survey to map everyday lifestyle and activity patterns in the neighborhood as well as what the residents valued most in the area. It was not until 2002 that the AKCS-E started the physical rehabilitation process.

The efforts of the AKCS-E were concentrated in three action areas, each with its own special character, needs, and opportunities: Burg al-Zafar Street and its immediate surroundings; the Aslam neighbourhood; and the Bab al-Wazir area and its extension along al-Darb al-Aḥmar Street.

A newly created joint company, equally shared by AKTC (50%) and the Social Fund for Development (SFD) (50%), the al-Darb al-Aḥmar Community Development Company (DACDC) carried out the implementation of the project.4 DACDC was not only responsible for the HRP but also the other complementary socio-economic as well as infrastructure and open space-related programs in the area.

The Rehabilitation Stages

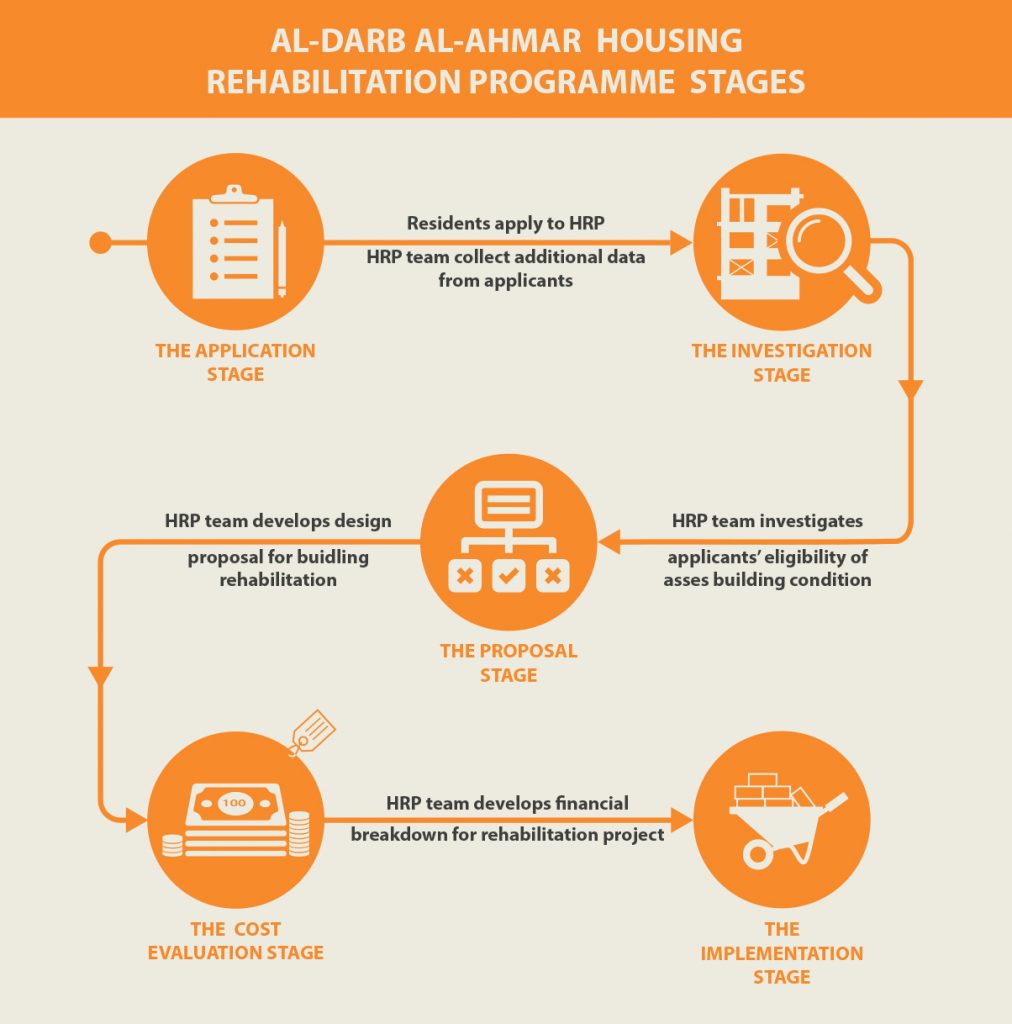

The housing rehabilitation was carried out through the following five-stage process:

The application and investigation stages: In these stages an interdisciplinary “social mobilization” team of architects, social officers, and financial officers collect data from applicants and analyze to investigate the eligibility of the applicant and the house to enter the program. The architect documents the condition of the building and housing units and assess whether a building could be rehabilitated. The social officer conducts a social assessment of each household to better understand the inhabitants and their needs, while the finance officer performs a financial evaluation of each household, assessing their financial assets and borrowing capabilities. An integral part of the HRP is the solidarity and communal financial contribution of all residents in the building based on their financial capabilities. Given the low average monthly income in ADAA, the HRP provided the residents with a loan mechanism managed by the AKAM. Accordingly, residents had access to affordable housing loans tailored to their individual needs: a minimum down payment of LE 5,000 was obligatory on all occupants but occupants had the choice to increase the down payment and minimize monthly installment amounts. They also got to choose the period over which they would pay their installments with a maximum of 6 years (Shehayeb, 2012). Loan rate were varying from 5% for housing units and up to 12% for commercial ones.

The proposal and cost evaluation and stages: Based on the information collected in the first two stages, architects, in coordination with the Aga Kahn Agency for Microfinance (AKAM), develop a financial as well as a design proposal for the rehabilitation of the selected housing units. The proposed design had to include basic amenities, such as kitchen and toilet, and proper ventilation for all rooms in each unit.

The implementation stage: The construction stage starts once a contract is signed between the building’s occupants (unit inhabitants and owners) collectively and the rehabilitation implementer (DACDC).

Resources and Funding

The first phase of the project was funded by the Egyptian-Swiss Development Fund, the Ford Foundation, the World Monuments Fund, and AKTC. During the second phase of the project, the AKTC was financially supported in its rehabilitation effort by the SFD, as well as the Ford Foundation, and the Canadian International Development Agency (UCLG, 2010). The HRP eventually ended in 2009 as the sources of funding came to an end. According to an interview with Dr. Dina Shehayeb, the housing consultant for the HRP, this reflected a “change of priorities” in the global agenda of donor’s interest, which increasingly was focusing on children, gender related programs and the environment.

Obstacles to Implementation

Contrary to what one would expect in such cost-extensive projects, funding – at least until 2009 – was not the project’s most critical issue. The main constraints were the legal documentation required before rehabilitation could start, as well as the need to convince the various parties occupying each single building to collaborate in the rehabilitation effort and to get the approval from the local authorities to launch the rehabilitation. We will review challenges encountered by the HRP team at the technical and administrative support levels.

Technical Issues

The HRP followed a participatory approach involving property owners and tenants in the design process. This approach helped promote a higher sense of ownership and resulted in avoiding most of the common post-occupation problems, it proved to be a very time and effort consuming process. Regarding rented units, the first challenge was to convince landlords – especially if their property is rented under the rent control legislation – that they will benefit from restoring it. The team was able to overcome this obstacle by showing the property owner the benefits he/she would reap. Tenants agreed to contribute to rehabilitation costs of their units instead of the owner (more on this below) and agreed to reasonable raise in the rent after the rehabilitation is completed. Additionally, property owners, who often lived in the same building, would benefit from their living space undergoing restoration, as well as being able to financially utilize any vacant units in the buildings that were in too dismal of a state to be on the market.

The second challenge was to find a middle ground between residents of a building (usually more than one) regarding their financial contribution to the restoration. In most cases, tenants would contribute in proportion to the percentage of total building area they occupy irrespective whether they are resident owners or tenants. Commercial and productive activities would contribute at a higher rate per square meter. The residents’ financial contribution was of about 8 to 10% in the first phase of the project. In the second phase, it increased to about 30 % and up to 50% in 2009. This is because of the increasing popularity of the project that made applicants willing to contribute a higher amount in the rehabilitation of their housing unit (Shehayeb, 2012).

Finally, a third challenge was to convince the community and the government about the validity of traditional techniques in order to address existing structural problems, while complying with conservation measures. In this regard, a body of knowledge was disseminated through training local workgroups and craftsmen, promoting appropriate building materials and techniques, providing technical advice, and producing construction manuals.

Overall, the social team would at times spend up to a full year to negotiations between tenants and owners to restore their houses. This was especially the case at the inception of the project. The restoration of the first four houses took 2.5 years. Later on, with the demand for the program increasing, a system of applications was introduced and the implementation process went down to about a year – 4 to 6 months for the initial negotiation and set-up stages and about 6 months for the construction work. During the second stage, residents were required to find another accommodation for the duration of the restoration process.

Legal and Administrative Issues

We have already mentioned that institutional and planning mechanisms needed to be revised to bridge the gap between official procedures and residents’ needs. An important effort was undertaken by the HRP to address the existing legal framework at the level of the neighborhood, particularly the 1973 Master plan. This difficult endeavor was facilitated through the established protocol with the Governorate of Cairo. Before initiating the implementation process, the team had to first confirm with local authorities that no demolition decrees were issued for the buildings – an uneasy task with the less than stellar archiving of the local district. A third administrative complication became apparent during the implementation process; it was often difficult to navigate the labyrinth of the local administration system to secure permits to upgrade the buildings’ vicinity, such as paving surrounding streets.

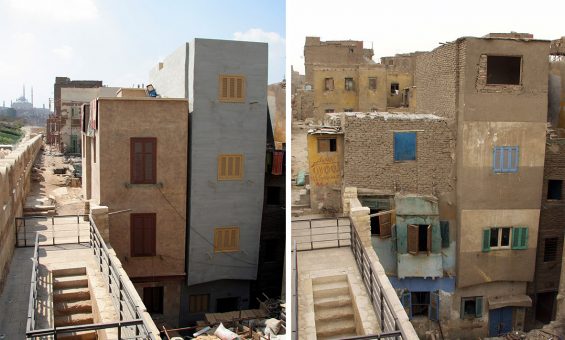

Outcomes

The impacts of the program were measured through a pre- and post-satisfaction survey covering all beneficiaries (Shehayeb 2003 and 2009). Overall, by 2010, more than 110 buildings were rehabilitated, providing improved living conditions through ensuring each unit had private bathrooms, kitchens, living spaces, natural light and access to safe water supply and sanitation. When the program came to an end, the program had more than 50 other applications pending hoping for enrollment in the housing renovation program, which proves that it was highly received by the ADAA community. The microcredit HRP loan was successful in achieving a repayment rate of 99.6% over a period of 5 years, showing that residents didn’t stay in long-term debt for taking a loan to upgrade their living condition. This can be partly attributed to the project’s finance officers appropriated evaluating each applicant’s repayment ability in the project’s initial investigation phase, only giving out loans proportional to applicant’s financial abilities.

Thanks to the negotiations between tenants and property owners as well as the agreements signed with public authorities, about 285 households in threat of eviction were provided secured tenure status. These were housing stock that were in danger of being demolished for their deteriorating structural condition – and as such tenants would be evicted – which were rehabilitated and tenants were able to stay in their homes.

In addition, the project contributed to increasing the livability of the ADAA as a whole, beyond the specific building renovations conducted. Although neighboring shiyakhas such as Batniyya were losing residents due to the continuing deterioration of the housing stock, there was an overall influx of new residents into ADAA in old and new buildings with new leases, some of them originally from ADAA (moved out and now returning to the area) and some from other popular districts in Cairo.5

Finally, while internal paint works and repairs to walls (72% each) were the most desired house improvements in 2003, this has decreased in 2009 to 48%. In 2009, structural repairs were seen as a highly-desired house improvement, with roof and staircase repairs ranking second in priority at 52% each. This decrease in priority of interior finishing may be an impact of the HRP, which worked on raising ADAA residents’ ambitions beyond just a coat of fresh paint inside their dwellings.

Institutional Impact

The HRP approach and implementation has resulted in innovations in several policy schemes. The SCA changed its demolition policies that had led to the eviction of hundreds of families from Al-Darb al-Aḥmar. Accordingly, Cairo Governorate revised the 1973 District Plan that was to allow for massive demolitions based on the SCA policies, and in 2008 ratified the new Conservation Plan for Al-Darb al-Aḥmar. In 2007, the National Organization for Urban Harmony (NOUH) identified the HRP as a best practice in its ‘Guidelines for Historic Areas’ to be implemented on the national level. In 2008, the Cairo Governorate modified the legal requirements for the rehabilitation of existing housing stock in order to promote a better rehabilitation process.

Sustainability

After the project ended in 2009, different tracks have been explored to ensure the sustainability of the project. One of them was to turn the DACDC into a local NGO. However, this never materialized as there were limited funds to sustain the social, housing, educational and financial programs associated with HRP.

Additionally, following the 25 January Revolution, the situation of the built environment in historic Cairo, as well as many urban areas in Egypt, has dramatically changed. The absence of the already compromised state control during 2011 has led to the demolition of a significant number of traditional buildings and flagrant building violations in terms of building heights that mushroomed all over historic Cairo. In addition, due to the economic downturn in the following years, many tenants have not been able to continue regular payments for the loan they contracted. The impact of 2011-2013 period on HRP building activities and households’ revenues still needs to be assessed to get a better picture of the current built environment status as well as loan reimbursement in the area.

Recognition and Opportunity for Repetition

The HRP model could be replicated in other historical neighborhoods and cities with a significant presence of ancient monuments and similar urban fabric and life patterns. Replicating some of HRP strategies and approaches have already commenced and other parties started to learn and benefit from the initiative on different levels. For example, the German development agency (GIZ), AKAM, RehabiMed (an EU funded project focusing on rehabilitation around the Mediterranean), and various Egyptian NGOs adopted the HRP approach between 2005 and 2008 in similar housing rehabilitation projects on smaller scales in Giza, Aswan Governorate, Historic Cairo, and various locations in Upper Egypt. In addition, as already mentioned, UN-Habitat listed in 2008 the HRP as a “best practice”.

TADAMUN’s vision: What can we learn from HRP?

What we learn from HRP is that the revitalization of historic cities requires deeper intervention than the physical upgrading of living spaces. The HRP took urban rehabilitation a step further towards addressing governance and poverty alleviation issues through a participatory design approach. As such, HRP represented an evolution of practices in Egypt from historic monuments to a policy focusing on area conservation, taking into account both the buildings and residents living in surroundings of these monuments.

The notions of product-based project and process-based project help us assess the nature of such an evolution. Product-based projects are driven by their vision about how the final result should look like. As an example, in areas of historical significance, the government’s priority has always been the monuments and tourism while residents come as an afterthought and are either evicted or forced to follow new regulations, but never considered as an original component of the neighborhood.

Process-based projects, such as the HRP, care about the way things should be done, more than the final output. What was different in al-Darb al-Aḥmar housing rehabilitation project is that it recognized residents as key stakeholders and a major component of the ADAA neighborhood along with the important monuments scattered in the historic area.

The HRP shows that an integrated approach – which benefits not only tenants that are given affordable and adequate housing, but also property owners, conversation agencies, etc. – can be realistically implemented in Egypt. The question is why hasn’t the comprehensive four-stage approach (technical, legal, social, and financial) been adopted and implemented by the state as a proven model to protect historic areas in Egyptian cities which are suffering from ailing urban fabrics, neglected (and often looted) priceless monuments, and struggling communities?

1. The Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC) is an international non-profit organization founded by His Highness Prince Karim Aga Khan IV who is also Imam of the Shia Ismaili Muslim sect. The AKTC is one of the numerous agencies of the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN).

2. The Al-Azhar Park project started in 1984 when the Agha Khan, announced his decision to personally finance the USD $30 million needed to transform an 80-acre dumpsite into a green public space for Cairo residents. The construction phase started in the mid-1990s and was officially completed in 2005.

3. Examples of buildings rehabilitated by the Aga Khan in the area include Umm al-Sultan Shaaban Mosque, Darb Shoghlan School, the Azlan Mosque and the Khayer Bek complex.

4. The Social Fund for Development (SFD) a state agency created in 1991 to support development projects in Egypt

5. The shiyakha is the smallest administrative unit in the Egyptian local administration system.

References

Aga Khan Trust for Culture. 2005. “Cairo Urban Regeneration in the Darb Al-Ahmar District. A Framework for Investment.” https://www.akdn.org/. https://www.akdn.org/sites/akdn/files/Publications/2005_aktc_cairo_regeneration.pdf.

Ibrahim, Kareem. 2011. “Housing Rehabilitation Study, Historic Cairo.” Rep. Housing Rehabilitation Study, Historic Cairo. Cairo, Egypt: Urban Regeneration Project for Historic Cairo-URHC. http://www.urhcproject.org/Content/studies/5_ibrahim_housing.pdf

Shehayeb, Dina. 2003. “Darb Al-Ahmar Phase II, Baseline Survey-Final Report.” Rep. Darb Al-Ahmar Phase II, Baseline Survey-Final Report. Aga Khan Cultural Services Egypt.

Shehayeb, Dina. 2009. “Post Implementation Survey-Final Draft Report.” Rep. Post Implementation Survey-Final Draft Report. Al Darb Al-Ahmar Community Development Company.

Shehayeb, Dina. 2012. “Living and Working in Historic Cairo: Sustainability of Commercial and Productive Activities. Background Study for the Management Plan.” Rep. Living and Working in Historic Cairo: Sustainability of Commercial and Productive Activities. Background Study for the Management Plan. Urban Regeneration Project for Historic Cairo – URHC.

UCLG. 2010. “Cairo, Egypt: The Al-Darb Al-Ahmar Housing Rehabilitation Programme.” Rep. Cairo, Egypt: The Al-Darb Al-Ahmar Housing Rehabilitation Programme. United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG) – Inclusive Cities Laboratory.

UN-Habitat. 2008. “Al-Darb Al-Ahmar Housing Rehabilitation Programme.” Rep. Al-Darb Al-Ahmar Housing Rehabilitation Programme. UN-Habitat.

Comments