Ecological Sanitation in Banī Suīf: An Innovative Solution to Rural Sanitation Problems?

Introduction

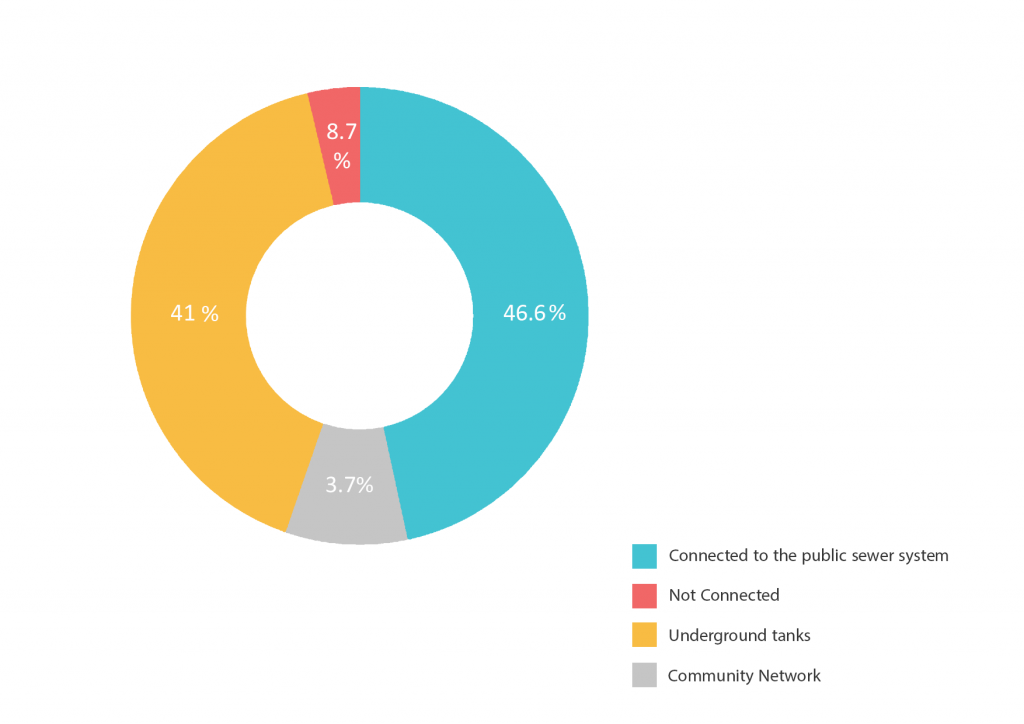

Over the past three decades the Egyptian government extended the potable water networks to increase services in urban and rural areas, resulting in 96% national coverage in 2004 and significant improvements to water quality and service consistency (Egypt Network for Integrated Development, n.d.). However, the sanitation sector did not receive the same level of investment, as 2006 statistics by CAPMAS demonstrate. Only 46.6% of Egyptian families are connected to the public sewage system, while the rest rely on informal methods of sanitation which are not always reliable. The resulting raw sewage overflow and leaking septic tanks and sewer lines significantly impact public health and the built environment. According to the World Health Organization, these leakages contaminate the groundwater, sometimes also seeping into potable water pipes and agricultural crops in rural areas. Contaminated water facilitates the spread of water-borne diseases such as diarrhoea and schistosomiasis. In 2004, water, sanitation and hygiene-related deaths amounted to 4.1% of total deaths in Egypt. In 2015 diarrhoeal diseases caused the death of 10.9% of children under the age of five. Additionally, leaking pipes and the collection of organic waste under homes can lead to the erosion of the soil. According to an expert, the Duwīqa rockslide which killed 98 people in September 2008 was partially caused by the improper disposal of sanitation which weakened the structural integrity of buildings in the area (De Albuquerque, 2010).

In light of these hazards–which are more evident in rural communities The Together Association for Development and Environment developed the Ro`ya project for the development of ‘Izabit Ya`cūb village in Banī Suīf governorate.1 Financed by EFG Hermes Foundation and implemented by the Association, the project encompassed the construction of a community-run wastewater treatment facility serving two villages in Banī Suīf. The initiative offers a successful alternative model of adequate sanitation system for small rural communities whose success is largely based on community engagement and technological innovation.

The Situation before the Initiative

The current coverage of the public sewage system in Egypt displays stark socio-economic and geographical disparities. According to a factsheet issued by the Centre for Economic and Social Rights in 2012, 88% of the urban population was connected to the sewage system, in contrast to only 27.4% of the rural population (2014). This means that the sewage systems and wastewater treatment sanitation services only cover 6% of Egyptian villages (Centre for Economic and Social 2014). Households not connected to public sewage systems rely on on-site sanitation methods and informal solutions to dispose of wastewater. Population growth, changes in water flows and rising water tables render those methods unsustainable in the long run (De Albuquerque, 2010).

One of the most common solutions is the bayyara system (soak-away system) and underground septic tanks. The construction quality of the tanks is often questionable and does “not ensure a hygienic separation of human excreta from human contact” (De Albuquerque, 2010). Additionally, leakages are not uncommon. Private companies have to be contracted to empty the tanks that are used by multiple families. The transportation of the wastewater to collection and treatment plants costs each family EGP 30 to EGP 50 each time, with some families having to empty their septic tanks on a weekly basis. The cost of pumping out septic tanks often impedes low-income households from emptying them on a regular basis, which leads to accumulation resulting in increased incidences of spillages and leaks. Occasionally and due to irregular monitoring from the government, the private operators dump the wastewater in local water bodies rather than at a treatment facility. Similarly, households not willing or unable to pay for such services dispose their wastewater in waterways or simply in nearby fields.

The Sanitation Sector in Egypt

Currently, the water production capacity in Egypt exceeds the capacity to collect and treat wastewater as only two-thirds of water produced is collected, and less than half of what is collected is properly treated (Egypt Network for Integrated Development, n.d). The government’s inability to expand the sanitation systems at an adequate pace and the poor performance of the sector (De Albuquerque, 2010) is largely caused by the fragmentation of authority, diffusion of public management and administration, financial challenges, and technical difficulties (Raslan, 2013).

An effort to reform the sector in 2004 led to the establishment of the Holding Company for Water and Wastewater (HCWW), a central agency tasked with the purification, desalination, transmission, distribution and sale of potable water as well as the collection, treatment and safe disposal of wastewater with governmental Holding Companies as its subsidiaries. Additionally, the government reformers created the Egypt Water Regulatory Agency to regulate and monitor activities in the water and wastewater sectors.

While the HCWW plays a key role, various other ministries and agencies are engaged in the water and sanitation sectors. For example, the Ministry of Health and Population is responsible for enforcing drinking water standards and inspecting wastewater treatment plants; the Ministries of Finance, Planning and International Cooperation secure and distribute investments and subsidies in the sector, while the Ministry of Industry is responsible for establishing standards for industrial activities (Soulie 2013). It takes little imagination to foresee how the multitude of actors can lead to coordination challenges and overlapping mandates make it difficult to ensure the accountability of the various agencies and ministries.

The Construction Authority for Potable Water and Wastewater in Cairo and Alexandria supervises investment in the water and wastewater sectors and the National Organisation for Potable Water and Sanitary Drainage plays that role in all other governorates except Suez. This investment is partially financed by the state with the support of foreign donors. A report by the Egypt Network for Integrated Development explains that the sector’s management assesses the sector’s investment needs then waits for the allocation of public resources. As the sector faces legitimate competition from other government agencies competing for budgetary commitments, insufficient funds are allocated to the sector. On the other hand, the majority of foreign donor funds are directed towards financing projects in high priority areas, technical assistance to the relevant public authorities, or towards the design of strategies for comprehensive coverage and estimations of the needed costs.

The government heavily subsidizes water and sanitation costs and the low tariffs levied on the consumers impede the HCWW and its subsidiaries from increasing their budget through a cost recovery approach.2 A study conducted in 2013 shows that the management and operation of the collection and treatment of wastewater costs the HCWW around 75 piasters/m3, whereas households are only charged 8 piastres/m3 with the gap subsidized by the government (Spit and Ismail, 2013) and cross subsidies from commercial and industrial users.3 Mamdouh Raslan, Deputy Chairman of HCWW, explained in a TV interview that in 2014 their expenses approximated EGP 10 billion and EGP 7 billion were collected from water tariffs and the state budget allocated around EGP 700 million allocated to the HCWW. This left the holding company with a budget deficit that hindered its ability to carry out its full responsibilities and network maintenance.

Given the magnitude of the costs needed to upgrade and expand the sanitation network the government cannot rely only on an expensive public investment approach and there is a need to pay attention and capitalize on the efforts already on the ground. One such efforts is the Ro`ya project which uses a constructed wetlands system to treat wastewater in rural communities in Banī Suīf. The implemented system provided a tailor-made, context-specific sanitation solution for the local community. Moving away from the conventional one-size fits all centralized solutions usually adopted by the government allowed the NGO to provide a more cost-effective solution which doesn’t require complicated and sophisticated technology and yet successfully addresses the community’s needs.

The Initiative

Since its inception in 2006 the Together Association for Development and Environment has been involved in implementing environmental projects across Upper Egypt. The association, headquartered in al-Minyā governorate, also implements projects focused on social service provision and economic empowerment. Engineer Sameh Seif, the Executive Director of the association and Chief Executive of the Ro`ya project which was established in 2008, explained to TADAMUN that the lack of adequate sanitation services is one of the most acute problems facing Egyptian villages. The groundwater contamination resulting from the disposal of untreated wastewater is particularly problematic given the high reliance on groundwater for drinking in rural areas. Thus, he saw the need to develop a small-scale and cost-effective solution to the rural sanitation problem.

Initially, the project consisted of constructing a small-scale water treatment plant to serve the residents of ʿIzbat Ya`cūb village in Markaz al-Fashn, in Banī Suīf governorate, one of the lowest ranking governorates in the human development index according to the 2010 Human Development Report. However, after EFG Hermes Foundation, the donor agency, conducted evaluation studies, they decided to finance a larger project aiming at the comprehensive and integrated development of the village. In addition to the sanitation component, Ro`ya project encompassed the physical upgrading of the village houses, the implementation of economic projects to increase household income, create green spaces in the village, as well as the construction of a community service centre inclusive of a bakery, training centre and a nursery. This was all complemented by awareness-raising campaigns on environmental and health issues.

The Sanitation System

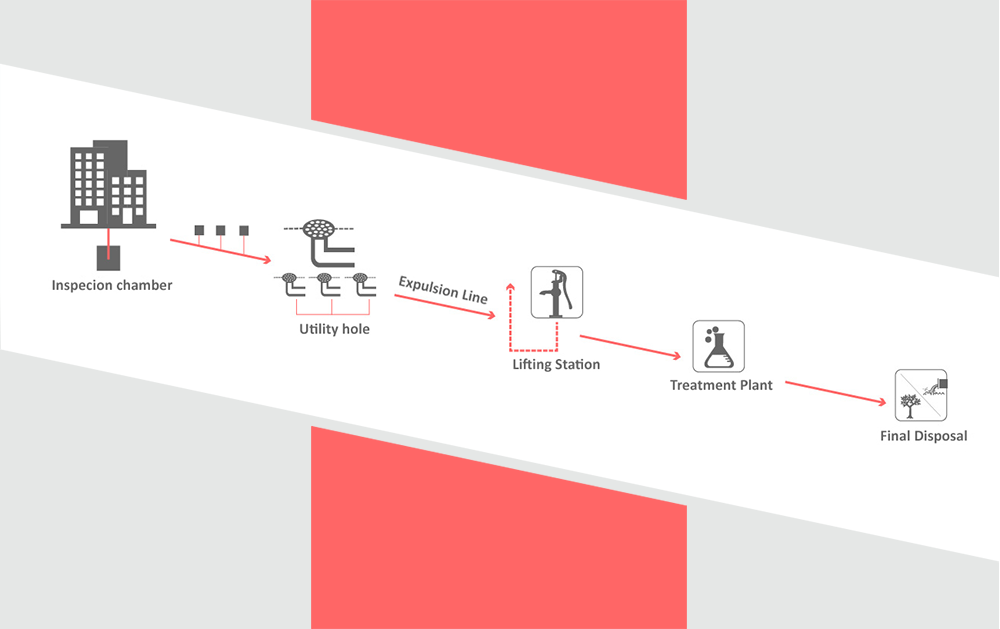

The project provided an integrated sanitation solution which typically consists of three distinct processes: the collection of wastewater and its transmission to a treatment plant, the treatment of the wastewater, and finally its disposal.

The new sanitation system added individual network connections to collect wastewater at the household level which is then transmitted to the local treatment plant. The treatment plant was constructed on a vacant land owned by the Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation in `Izbat Ya`cūb, serving the village’s 5,000 residents, in addition to the 4,500 inhabitants of nearby Ga`far village.

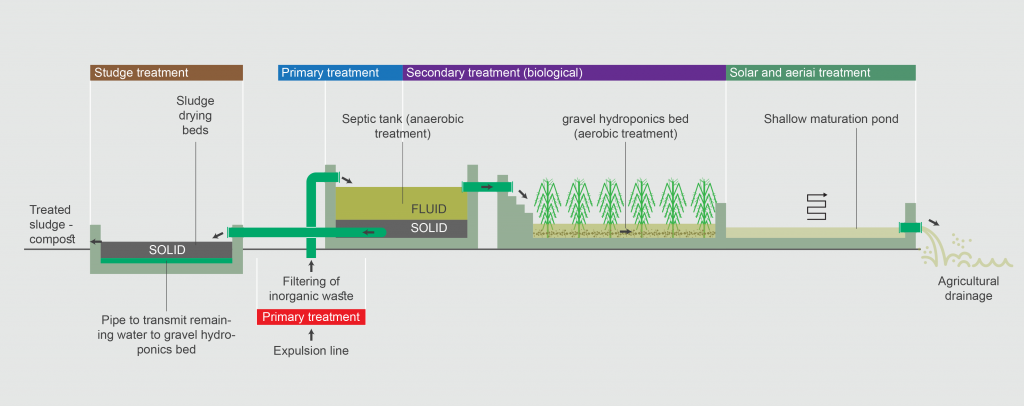

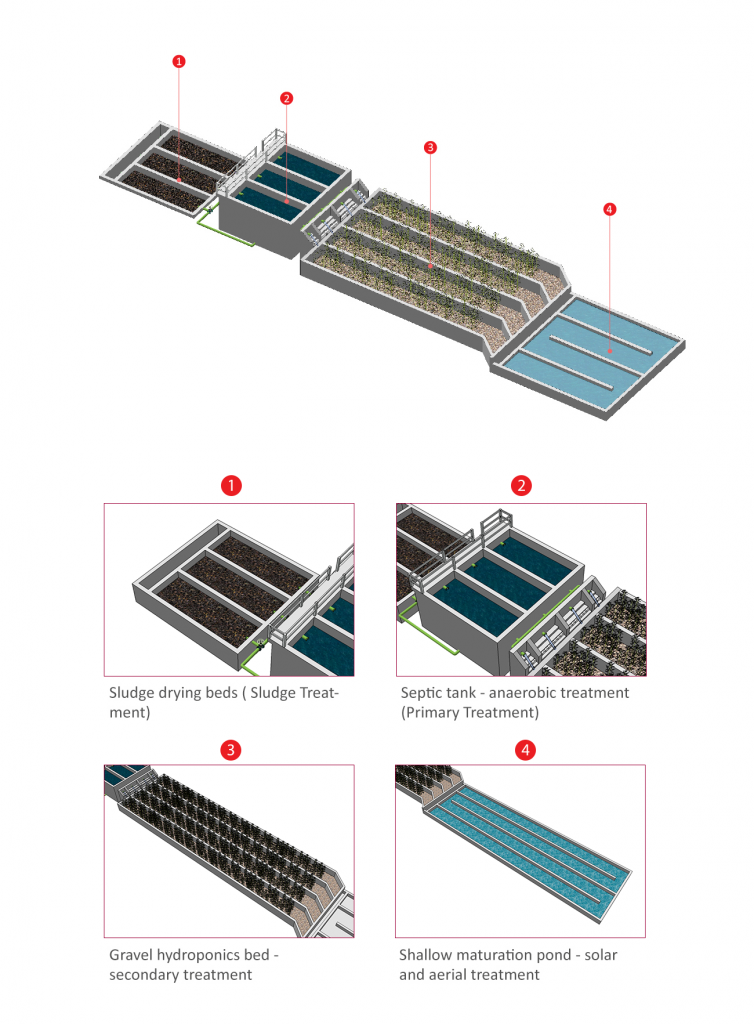

The treatment takes place over three stages at the treatment plant. In the first stage, the septic tanks receive the wastewater from the pumping station where the inorganic waste has been filtered from the water. In the tanks, the water is treated using anaerobic bacteria and is then aerated at the outlet of the tank through a low dam before it flows into an oxygen injection chamber. In the second stage, the water sits in a gravel hydroponics bed where the organic matter is treated by aerobic bacteria and filtered from impurities. The water then flows into a shallow maturation pond to undergo solar treatment. As per the regulations, the treated water then flows into the agricultural drainage network. In the third step of the treatment the sludge of solid wastes that was left in the septic tank in the second stage is spread and dried in drying beds. The sludge can then be mixed with animal excreta and agricultural waste to become rich compost. Alternatively, it can be used as biogas. Recently, the National Research Centre in collaboration German Development Cooperation (GIZ) installed a unit in the treatment plant to produce biogas. The wastewater collected in the drying beds is lifted once again to the air injection chamber.

The resulting treated waste abides by the standards set by the Ministry of Environment for treated wastewater. The treated waste is regularly sampled and tested by the Banī Suīf Potable Water and Sanitation Company to ensure the continued quality of the treatment.

Resources and Funding

According to the Together Association, the costs of the integrated village development project, which included the upgrading of the houses and the implementation of economic development projects reached EGP 28 million. While the costs for implementing the sanitation project were initially estimated at only half a million EGP, the expansion of the project demanded a bigger treatment plant to cover two villages instead of one, which increased the costs of the component to EGP 1.75 million. However, it is important to note, that this cost projection did not cover the cost of the land on which the treatment plant was built. As mentioned earlier, the land originally belonged to the Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation, which gave permission to the association to use its land for the project. In addition, it does not account for the resident’s voluntary labor and/or contribution of some material for the project which amounted to 15% of the project costs.

Based on these costs, the association estimated the cost per person for the construction of the project to be at EGP 210 in 2010. Given the later price increases in material and labor of around 30% over the following two years, Engineer Sameh Seif estimated that a comparable project would have cost EGP 300 to 350 per person in 2014.

Project Implementation and Management

The Together Association was responsible for the design of the project and its management during the implementation phase. Representatives from the Ministry of Agriculture, the Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation and the HCWW visited the site and monitored the project’s progress during the implementation phase. Additionally, the Together Association’s financial management of the project was monitored by EFG Hermes as the donor agency and the Ministry of Social Solidarity and the Accountability State Authority.

Upon its completion, the management of the project was handed over to the already existing, but previously inactive, Community Development Association (CDA) of ʿIzbat Ya`cūb.4 The Together Association’s role is currently limited to monitoring and providing technical assistance when needed.

Sustainability

For community-led efforts to be successful, social solidarity needs to be built and the cooperation of the authorities needs to be secured (Walnycki, 2015). Together Association’s initiative presents an interesting example of the engagement of civic organizations and community participation in the planning, implementation and monitoring of a public infrastructure in Egypt. The social solidarity needed to work towards a common goal was built through community workshops, meetings and awareness-raising campaigns. Initially, people did not show much interest, because their understanding of proper sanitation was limited to implementing small upgrades to the common pit latrines. The community workshops were used to explain the importance of the project prior to its implementation. Once they understood the importance of sanitation and hygiene and the cost savings entailed, they gave their support to the project. Nonetheless, in the early days of the project’s operation, some families continued to dispose of their waste in canals, as they feared their septic tanks might overflow since that was so common before the project. In response, the association intensified its awareness campaigns, and over the three years following the project’s implementation there have been minimal cases of wastewater overflow or any blockages. The residents now feel very confident in the project and their cash and in-kind contributions account for nearly 15% of the project’s costs.

Currently, the Community Development Association (CDA) of ʿurrit Ya`cūb operates the treatment plant. The capacity building component in the project’s design facilitated the smooth operational handover of the treatment plant to the CDA. The Together Association had trained the CDA of ʿIzbit Ya`cūb about the administrative and financial aspects of managing the project such as acquiring approvals from local authorities, collecting fees from residents, and recording cash inflows and outflows. On the technical level, the Together Association, in collaboration with the CDA of ʿIzbit Ya`cūb, has ensured that four to six young people are involved in all the steps of technical implementation and are technically trained to deal with incidents of blockage, lifting motor malfunction, or problems with treatment plant basins. According to Engineer Seif, this local management ensures that service provision and maintenance will be timely and efficient. If the system exhibits problems or malfunctions, complaints are made to the CDA, which processes them promptly. If the service was run by the Banī Suīf Potable Water and Sanitation Company he doubted whether problems or complaints would be processed as quickly. At the same time, the technical performance of the system and the financial operations of the NGO were monitored by state authorities and the donor agency.

The project is financially sustainable due to the EGP 5 monthly fee paid by each household. The EGP 3,000 to 3,500 monthly fees collected from ʿIzbat Ya`cūb, in addition to the EGP 500 collected from Ga`far village for using the treatment plant, cover operations and yearly maintenance costs.

The implemented constructed wetlands system in itself is self-sustainable as it mimics natural cycles and uses bacteria and natural processes to treat anthropogenic discharge. Therefore, as opposed to mechanised systems, the wetlands system requires lower maintenance efforts when it closes for one week on a yearly basis to trim the vegetation. This approach translates into lower lifetime costs than conventional treatment systems.

Opportunities

At the core of the success of this initiative was the presence of a locally grounded and creative NGO. As Engineer Sameh Seif explained to TADAMUN, to design the sanitation system to be implemented, Together Association’s team surveyed the existing sanitation projects and created a system which combined aspects from different projects to create the most suitable design for the targeted site. Another crucial success factor was the availability of the funding and the flexibility of the donors to change and add elements to the initial proposal which enabled the association to implement a more comprehensive project that serves more people. Constructing a larger treatment plant meant the project could serve two villages instead of one; and demolishing the village houses due to their dilapidated state and reconstructing them translated into higher willingness from the residents to participate in the wastewater treatment project. The sufficient funds also enabled the association to hire experienced administrative and technical staff to support the project’s design and implementation. In addition, the donor’s good political relationship with the authorities facilitated the process of obtaining permits from the different ministries, particularly the Ministry of Social Solidarity.

Replication and Future Plans

The Together Association was able to replicate a less costly version of the sanitation system in 2014 in Banī Shaitān village in al-Fayyūm governorate. The construction of the wastewater treatment plant was funded by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). The land needed for the construction was donated by a local resident, who wanted to re-use the treated wastewater since water is scarce in al-Fayyūm for agricultural use and he planned on using the treated wastewater in his fields. The Ministry of Environment granted the Together Association a permit to reuse the effluent for the irrigation of non-edible plants. Additionally, Engineer Sameh Seif, was chosen by Siemens Foundation to be part of a global knowledge sharing group. Through this involvement he was able to implement similar sanitation systems in Peru and Guatemala.

It seems problematic that international agencies realize the utility and efficiency of this approach but the Egyptian government seems unable still to move beyond its costly, less financially and environmentally sustainable centralized sanitation system. During his interview with TADAMUN, the Executive Director recalled that acquiring permits from the relevant ministries and entities was a different experience in a similar project in al-Fayyūm Governorate. Securing the permits took over a year, partially due to the period of regime change over the past few years and corresponding fluidity in various ministries. He believed that bureaucratic obstacles may not allow the model to be replicated elsewhere or scaled up. Although he approached many governors and governmental agencies numerous times to launch this sustainable and environmentally sound approach to sanitation elsewhere, government entities showed little interest compared to great interest in the approach from the private sector and international organisations. Even when certain government officials were intrigued by the initiative’s solution other key entities such as the HCWW or the Ministry of Housing, Utilities and Urban Planning viewed those small scale solutions with contempt. This can potentially be traced back to the institutional and regulatory frameworks’ aversion to innovation and out of the box solutions. This is reflected in the absence of alternative sanitation systems and integrated solutions in the government’s wastewater management practices. It was only after Engineer Sameh Seif was awarded the Takrīm Initiative award for innovations in Sustainable Development and received significant media coverage that some government officials started showing interest in the project.

TADAMUN’s Vision

The Initiative’s Contextualised Approach

The initiative has been remarkable on multiple levels. Spatially, it presented a decentralized system serving only two villages, in contrast to the government’s centralized cluster approach for rural areas with each cluster planned to serve up to 100,000 inhabitants in a number of villages (Egypt Network for Integrated Development, n.d.). The spatial decentralization had several impacts on the size of the treatment plant as well as the technical specifications of the sewer system and the treatment plant which consequently reduced the costs needed.

From a technical view point, the wastewater treatment technology is a natural system as it mimics biological cycles which use the natural functions of vegetation and anaerobic processes to purify the wastewater making it ecologically sound. Additionally, the system is not mechanized and thus, requires less energy which not only limits the emission of polluting greenhouse gases, it also makes it more sustainable in the light of the current energy crisis Egypt is experiencing. The implemented technology differs significantly from the activated sludge treatment technology used by the HCWW which is a highly mechanized system. While this technology produces effluent of high quality, the system requires energy, highly-skilled labour and the availability of mechanical spare parts which make it costly. Therefore, it is mainly feasible for large-scale centralized systems which serve millions of people. The large-scale central stations not only require constructing larger plants on larger plots of land, the wastewater collection process used for central stations necessitates wider and longer expulsion lines, stretching over long kilometres, installed in great depths. This makes it financially unattractive to connect small and remote villages.

Together Association’s project is considered one of the most comprehensive examples as it encompasses an integrated approach to the sanitation services from the collection to the treatment of the wastewater followed by the disposal of the effluent. The initiative has built and successfully implemented an efficient and cost-effective approach to providing sanitation service to these two villages. Engineer Sameh Seif estimates that his project’s cost/person is approximately 1/20th of the cost that the government would have to bear, if it had implemented a traditional wastewater network.

Sanitation Services: whose responsibility?

The importance of water and sanitation services (WSS) is highlighted in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals with Target 6.2 encouraging states to “achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all and end open defecation, paying special attention to the needs of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations” by 2030. The adequate provision of WSS and universalizing their access is a cornerstone for the improvement of public health (Castro and Heller 2009). In addition, access to public services including WSS is an essential part of the right to adequate housing as detailed by the International Covenant of Economic, Social, and Cultural rights. Yet, there is no consensus on the international level that WSS constitute an inalienable human right. Consequently, it is still being debated whether governments bear the responsibility of providing citizens with the basic right of WSS or if the private sector has a role to play to provide more efficient services. The former opinion considers WSS as a public good with little incentives for individuals to invest in and, therefore as the obligation of the state. It argues that the universal access to such services as a fundamental and social right of citizenship which cannot be subjected to market principles and the payment capacity of users.

Theoretically, in the public model of service provision the utility belongs to the local community and accountability is guaranteed through elected officials. However, critics argue this does not always hold true in reality, in practice one finds a lack of separation between policy and delivery functions that allows for the interference of politics in operational considerations which ultimately leads to inefficiencies and inadequacies of the system (Castro and Heller, 2009). Similarly, lack of proper monitoring and oversight can lead to corrupt institutions which do not fulfil their responsibilities. As such the organisation of WSS on the basis of market principles through Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) or Private Sector Participation (PSP) was largely encouraged by multilateral institutions and international organizations (Castro and Heller, 2009). This essentially made a basic right such as WSS a source of profit for private capital. Many countries embraced this view and the 1990s was the decade of WSS privatization – on a global level – with the expectation of achieving higher efficiency for lower prices and attracting investments. However, these efforts have not always been successful with lack of investments in infrastructure, price increases, environmental hazards and injustices in provision (Balanyá, 2005). This contributed to an increasing trend of taking back public control over water and sanitation management. The Transnational Institute documented 180 cases of cities, regions and countries “re-municipalising” versus very few cases of privatization in the period of 2000 to 2014.

The Egyptian Constitution does not oblige the state to offer WSS. Sanitation services, including the collection of wastewaters, its treatment and disposal have been traditionally under public control with the only private involvement in the sanitation system at the treatment phase (Arefin, in preparation). In June 2009 Egypt awarded the first land-mark concession for a wastewater treatment facility in New Cairo. The PPP to build, operate and transfer scheme was awarded to a joint-venture of Egypt’s Orascom Construction Industries and Spain’s Aqualia. Public-private partnerships have since been used to attract investment and implement projects in the sanitation and wastewater sectors, most notably in new cities in line with the government’s history of relying on large-scale central stations.

Despite large investments made in the sector, in a 2012 statement, Dr. Abdel Qawi Khalifa, the former Minister of Utilities, Drinking Water and Sewage, indicated that around EGP 80 billion are still needed over the next 10 to 15 years to achieve universal coverage of sanitation services.5 To overcome the lack of funds needed for a universal coverage in rural areas the government plans to connect unserved villages to nearby plants with excess capacity until funds become available to construct new treatment plants. Yet, inadequate financing suggests that the sanitation network will not be equally accessible to rural residents and the centralized system’s poor performance will continue.

Service gaps in Egypt and globally are often filled by independent service providers, self-provision, NGOs and community based organization (CBOs), or through partnerships between local authorities and community-based organizations in which they co-provide the service. The term co-production has been defined by Ostrom (1996) as the “process through which inputs from individuals who are not “in” the same organization are transformed into goods and services.” There is a broad range of possible collaboration options which are often thought to be more efficient and cost-effective. For example, often such arrangements bring alternative, more efficient technologies, have access to capital or offer more credibility with local communities. For example, the community-owned and managed Orangi infrastructure-upgrading program in Pakistan has provided improved sanitation services to over 1 million people and influenced sanitation provision nationally. Despite the potential efficiency improvements and cost-savings, co-production can be viewed as a way to pass responsibilities to communities which can make it a cause for cynicism and anxiety.

Moving Forward

The urgency of providing adequate sanitation to all stems from many aspects. Lack of adequate provision poses serious public health threats to unconnected citizens. These threats are not only pertinent to rural areas but the water pollution resulting from the dumping of untreated wastewater into local water bodies have far-reaching effects even to residents of urban areas downstream of the Nile. The water pollution exacerbates Egypt’s water problems. In 2010 renewable water available to Egypt was less than 800 cubic meters per capita per year making it a water scarce country. As renewable water sources cannot be expanded and demand on water is continually increasing due to population increase and economic activities, the country will be facing a shortfall in available water supply. Immediate action and policy changes are needed as the impacts will only be intensified by forecasted climate change impacts. The use of treated wastewater presents an attractive alternative to cover the expected shortfall in water supply.

Despite the success of this initiative, the government has not sought to institutionalize it. On the contrary, the bureaucracy legacy of the public administrative system – the lengthy process of obtaining permits and the government’s resistance to new innovative ideas – remain strong impediments to the wide replication of the adopted system. Raymond et al. (2012) argue that rural sanitation has been approached with an “all or nothing” mentality which prevents the implementation of small-scale, intermediate but affordable solutions. Certainly each approach to WSS provision carries opportunities and constraints and there cannot be a one-size fits all solution to every context: small-scale will not always be cost-effective and decentralized will not always mean efficient. However, successful initiatives such as this one which proves that participatory, efficient and affordable solutions can be found merits a closer inspection to draw the lessons learnt and to replicate them where they can make a positive contribution.

Works Cited

Arefin, Mohammed. 2016. “Waste, Capital, and Desire: The Politics of Sanitary Infrastructures in Cairo.” PhD Dissertation, University of Wisconsin. University of Wisconsin.

Balanyá Belén. 2005. Reclaiming Public Water: Achievements, Struggles and Visions from around the World. Amsterdam: Transnational Institute.

Castro, Jose Esteban., and Heller Léo. 2009. Water and Sanitation Services: Public Policy and Management. London: Earthscan.

Center for Economic and Social Rights. 2014. “The Right to Water and Sanitation.” Fact Sheet.

Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS). 2009. “Sanitation in Egypt.”

De Albuquerque, Catarina. 2010. Report of the Independent Expert on the Issue of Human Rights Obligations Related to Access to Safe Drinking Water and Sanitation. UN Human Rights Council. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/685823?ln=en

Egypt Network for Integrated Development. (n.d) “Rural Sanitation In Egypt.” Policy Brief.

Ostrom, Ellen. 1996. “Crossing the Great Divide: Coproduction, Synergy, and Development.” World Development, 24(6), 1073-1087.

Raslan, Mamdouh. 2013. “The Legislation Framework for Water Services in Egypt.” Presented at the First Aquaknight International Conference, Alexandria, Egypt, May 15, 2013. http://docplayer.net/41187293-Eng-mamdouh-raslan-holding-company-for-water-and-wastewater.html

Reymond, Philippe, Rifaat Abdel Wahaab, and Moustafa Moussa. 2012. Small-Scale Sanitation in Egypt: Challenges and Ways Forward. EAWAG Aquatic Research. https://bit.ly/2QcUYSk

Soulie, Michel. 2013. Review and analysis of status of implementation of wastewater strategies and/or action plans; National report Egypt. Sustainable Water Integrated Management (SWIM).

Spit, Jan, and Ashraf El-Sayed Ismail. 2013. “Towards Innovative Sanitation Facilities and Treated Effluent Reuse for Rural Areas in Egypt.” http://www.janspitcsdelft.nl/downloads/150/file_block/5c76c2a6ebc98821238406062e27e2de

Walnycki, Anna. 2015. “Urban Water and Sanitation Services in the Global South.” Presentation, University College London.

1. Banī Suīf is a largely agricultural governorate, located approximately 70 miles south of Cairo.

2. The universal subsidization policies in Egypt adopted decades ago ensures that public services, including water and sanitation are affordable to all. Government subsidies on drinking water reached EGP 1.2 billion in 2014. In efforts to cut its subsidy bill the Egyptian government has been continuously increasing water tariffs for residential and commercial consumption over the past few years, although there is significant opposition to price increases from many sectors in Egypt.

3. 100 piasters = 1 EGP.

4. In the late 1950s President Nasser set up social units, wihda ijtimā`yyia, to develop local communities by providing health and educational facilities, consumer cooperatives, and banking facilities among other activities. They were public sector entities. Later the government encouraged residents to participate in those development efforts and following Law No. (32/1964) the social units became CDAs which presented a shift from top-down development efforts to a more community-based approach. Before the start of the Ro’ya project, Engineer Sameh Seif claims that the CDA of ʿIzbat Ya`cūb was inactive and that the project spurred the CDA to assume a more active role again.

5. The Ministry of Utilities, Drinking Water and Sewage later merged with the Ministry of Housing to form the Ministry of Housing, Utilities, and Urban Development.

Comments