Imbāba

More than many other parts of the capital, Imbāba has carried throughout its history a considerable legacy of stereotypes and preconceived notions. While its name has shone from time to time in media, books, and speeches, as well as in the political chambers of the government, it has just as often been forgotten and derided. It gained prominence at the end of the nineteenth century, during the construction of the railway bridge which bears the district’s name, then again when its factory workers’ compounds were being built during the 1940s and 1950s. It reached the peak of its fame in the nineties as a battlefield between the government and the political Islamist parties. Living for years under the stigmas of extremism, poverty, violence, and lack of planning, Imbāba today is a society unique in its diversity and rich in its details.

Imbāba in Numbers

Governorate: Giza Governorate.

District: North Giza District

Area: 8.28 square Km.

Population: 695002 inhabitants in one governmental estimate1, one million inhabitants; more in other estimates.

Various government sources quote different figures regarding the population of Imbāba, the largest being close to 700,000, while several researchers claim that the population of Imbāba reaches one million inhabitants, without mentioning their sources (review: Bayat and Denis 2000; Davis 2006.) Its residents think the number is much larger. One youth in Imbāba, having an interest in public affairs, and having monitored elections in recent years, told us that the number of the registered voters in Imbāba is nearly 1.2 million, all of whom are registered to addresses within Imbāba. Additionally, there are a large number of Imbāba residents, especially in the areas of al-Munīra al-Gharbiyya, whose ID cards are still registered to addresses in Upper Egypt and other governates, despite residing in the area for decades.

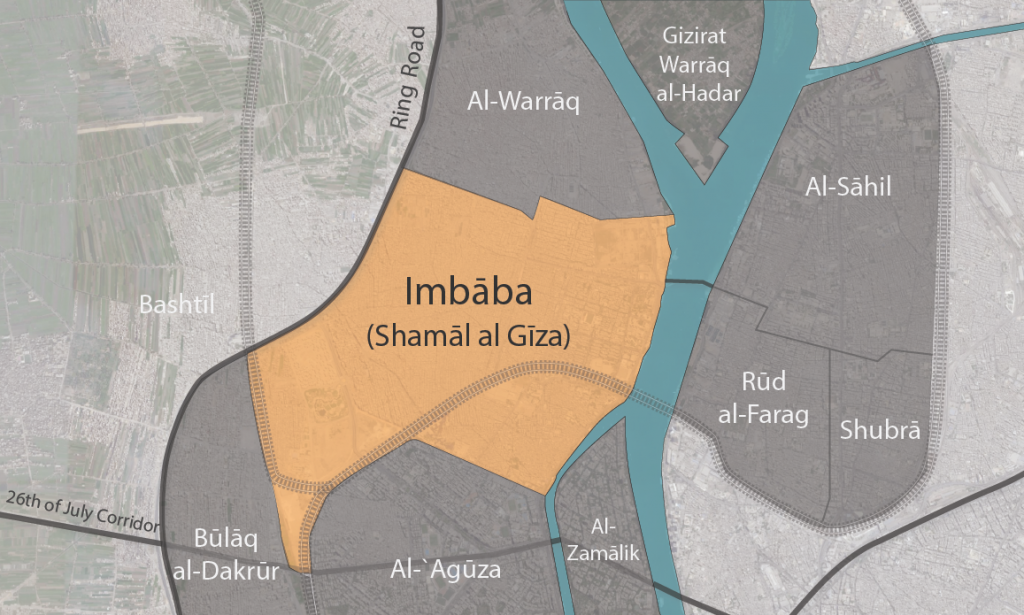

Imbāba officially comprises2 all areas within the scope of the North Giza Administrative District. This means that in this article we are monitoring a large geographical area, bounded by the Nile to the east, and the ring road to the west, separated from al-`Agūza district to the south by al-Sūdān and al-Maṭār streets, and from al-Warrāq District to the north al-Nasr, ṭarḥ al-Boḥūr and al-Qaomiyya al-`Arabiyya streets. Until recently, this geographical area was included in a single administrative section3 – The Imbāba District – divided into nine zones. These zones were re-divided, and a new district was created, so that currently, Imbāba is divided into two administrative sections that include 18 zones:

- The first division includes 11 zones, which are: Mīt Kardak (Imbāba al-Qadīma), Baḥarī Awal (Ard al-Gam`iyya), Baḥarī Khamis (al-Munīra al-Sharqiyya), al-Masaken al-Sha`biyya (Madīnat al-Taḥrīr), Tāg al-Dowal (Imbāba al-Qadīma), Gizīrat Imbāba, Kafr al-Shawām (Imbāba al-Qadīma), `Abd al Na`eem (`Izbat al- ṣa`ayda), Sīdī Ism`aīl (Gizīrat Imbāba), and Madīnat al-`Omal.

- The second division includes seven zones, which are: Qiblī Thānī (al-Munīra al-Gharbiyya), Qiblī Rabi` (`Izbat al-Maṭār), Baḥarī Thānī (Arḍ al-ḥaddad), Baḥarī Thalith (al-Munīra al-Gharbiyya), Qiblī Thalith (al-Munīra al-Gharbiyya), Masaken al-Maṭār, Mīt `Okba Thānī (al-Baragīl which includes: al-Munīra al-Gharbiyya, Madīnat al-Amal, al-Baragīl, Arḍ al-ḥaddad and `Izbat al-Maṭār.

The Story of Imbāba

We do not have a definitive date for the beginning of Imbāba, but we do know that it originated as a village near the Nile and has been named Imbāba for centuries. It is said that “Imbāba” is a distortion of the original name Nabāba mentioned by the Egyptian Historian Taqī al-Dīn al-Makrīzī (1356 – 1441). He is considered the most important historian in Egypt during the middle ages – the Mamlūk era. His manuscript “Homilies and Consideration by Mentioning Plans and Effects”, known as The Makrīzī Plans, is a description of the planning of Cairo and Egypt, its buildings and its topography. After him came `Abdel Rahman al- Gabartī (1753 – 1825) in his comprehensive description of Egypt “History of Egypt: ‘Ajā’ib al-Athār fi ‘l-Tarājim wa’l-Akhbār.”. Famously known as “The History of al-Gabartī”, it is one of the most important books to chronicle Egyptian towns and villages during that period. In spite of this, Imbāba never recieved an adequate and satisfactory description of its buildings, its residents and their activities like other areas of the capital on the eastern bank of the Nile, as it was no more than a modest village whose name was only mentioned in the history books when it happened to be the site of momentous events.

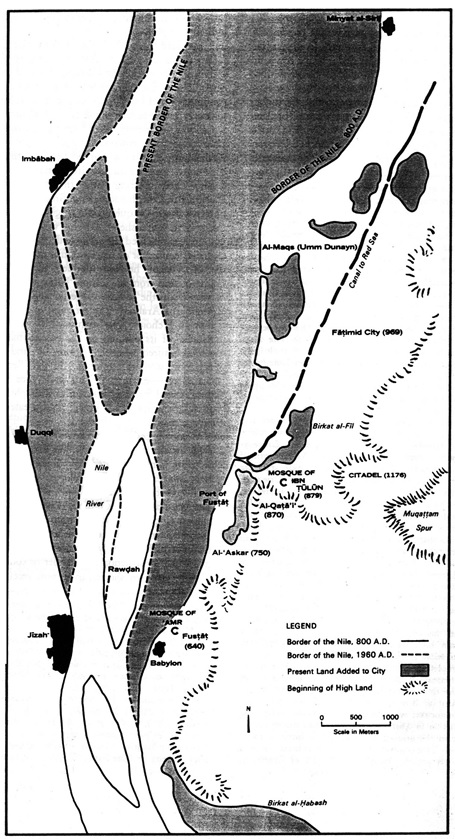

A map of Cairo showing the location of major urban communities in year 1397 A.D (Source: Cairo 1001 Years of the City victorious, Janet L. Abu-Lughod

Religious folk legend: Sheikh Ismaīl “al-Imbābī”

For centuries, the earliest mentions of the name “Imbāba” in history were linked to the popular Sufi myth, “Sīdī Ismaīl al-Imbābī” the righteous man of God. Imbāba was the village chosen by Sheikh Ismaīl to settle in, and he lived there until he died. Subsequently, its name became attached to his last name. His dargah and then his mosque were built in the same spot where he had lived, and are still there now.

It is mentioned in the oral history of Sufism that “Al- `Ārif bi Allāh, Ismaīl Yūsif al-Imbābī” was the son of a Sufi, one of the followers of al-Sayyid al-Badawī – the most famous Sheik in Ṭanṭā. As he grew up he became a protégé of al-Badawī and his successor, `Abd al-Met`āl, studying under them and inheriting their status. He came to Cairo and settled in Bulāq, but the residents rejected him, so he crossed the Nile to the opposite side (McPherson, 1941). Residents often repeat the legend that “he crossed the water on a handkerchief”. He lived in Imbāba until the end of his life. Until this day, the area around the dargah of Ismā`īl al-Imbābī, called Kafr al-Sheikh Ismā`īl, provides the oldest evidence that the settlement of Imbāba, has been in its current location for many centuries.

Some residents of Imbāba and devotees from other areas, to this day, believe in and repeat stories about his miracles. They visit his dargah to seek his blessing and intercession. They also hold an annual celebration for him, and people come from all over Egypt to celebrate his birthday “the birthday of Sīdī al-Imbābī”. It is one of the oldest Egyptian celebrations, as it is just as old as that of Sayyid al-Badawī, which is more than 700 years old. Egyptians at that time had not yet begun relating their dates to lunar months, and therefore, the date of his birthday is the tenth of the month Baounah in the Coptic calendar. This falls on the same day the Ancient Egyptians waited for the Isis teardrop, which fell in the Nile because of her grief over the chopped limbs of her husband. The celebration of that night, known in the inherited popular culture as “night of the drop” continued (McPherson, 1941). These rituals during the night of the drop have cast their shadows on the celebration of al-Imbabī’s birthday. Boats fill the Nile on the night of his birthday as they used to on the night of the Isis “drop” before that. Current residents of Imbāba Island say that they’ve seen crowds coming in their thousands to commemorate the birth of al-Imbābī; sleeping in the streets for nights at a time, in preparation for “the Big Night”. The residents of the island prepared banquets and donated food and blankets to attendees of the celebration.

Despite the residents continuing to seek blessings at the dargah and the continued survival of this legend in the area around it, the celebration on the birthday of Sīdī Ismaīl has (like many similar celebrations) recently declined. This is due to several interrelated reasons, including the decline in Sufism and folk legends, which has impacted the number of enthusiasts coming to the celebration. This is in addition, to the spread of religious ideologies that condemn these celebrations and consider them fads or prohibit them. This became apparent in 1946, when members of the “Muslim Brotherhood” group in Imbāba lodged a complaint to the police against what they described as “violations” during the celebration. Another reason for this decline, according to some political analyses, is the increasing securitization and the government’s desire to exercise control over public spaces in Greater Cairo, and all the cities in Egypt more generally. Celebrations stopped completely in recent years – especially after 2011. Residents attribute this to security considerations, as the Imbābī dargah is located directly behind the police station building.

The military legend: The battle of Imbāba

A great historic battle took place in Imbāba during the French Campaign in Egypt; documented in the writings and paintings as one of the most important battles in the history of the French Army, led by Napoleon Bonaparte. It is signifigant for the fact that Napoleon originated a new military tactic, the infantry square formation, which was considered one of his most important contributions in the military arts. He destroyed most of the Mamlūk army in Egypt at the time, to the extent that they were forced to retreat from Egypt to Syria and rally their ranks. It was considered in French literature as an important victory for Europe, after the French Revolution, over the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East.

This battle took place on July 21st 1788, following the occupation of Alexandria. Napoleon’s army moved to Cairo, where it encountered the Mamlūk forces led by the Georgian Mamlūks “Murad Baig” and “Ibrahim Baig”. He defeated them in two battles; the first a minor battle on the eastern bank, and the second a large, decisive battle in which his army met the Mamlūks’ army near the village of Imbāba on the western bank of the Nile. Various sources quote different numbers for the dead and wounded on the Egyptian side led by the Mamlūks. After the crushing defeat of the Mamlūk army, Mourad Baig fled to Upper Egypt; Napoleon entered Cairo and there laid the foundations for a new local government that did not last for long. Napoleon later named the battle, “The Battle of the Egyptian Pyramids, (al-Ahrām al- Masriyya)”, because the Pyramids could be seen on the horizon from the battlefield; he considered them to be historic witnesses to his victory.

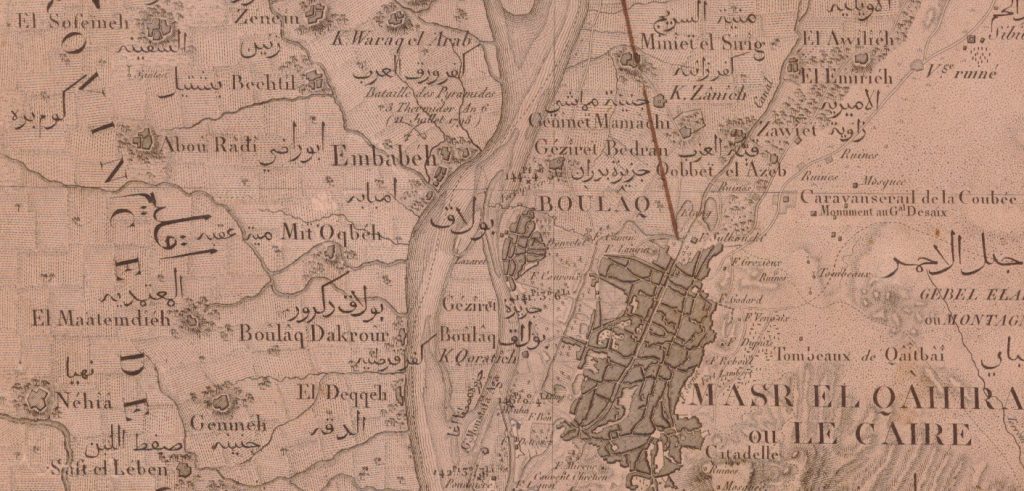

The map of Cairo in 1826 from the Geographical Atlas, one of the parts of the famous work, Description of Egypt, by the scientists of the French Campaign, the village of Imbāba appears next to similar historical villages in Giza, source: Bibliotheca Alexandrina.

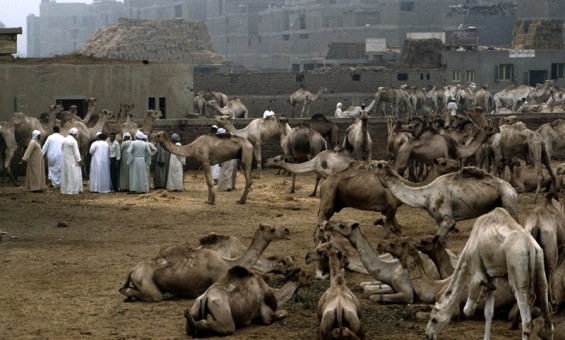

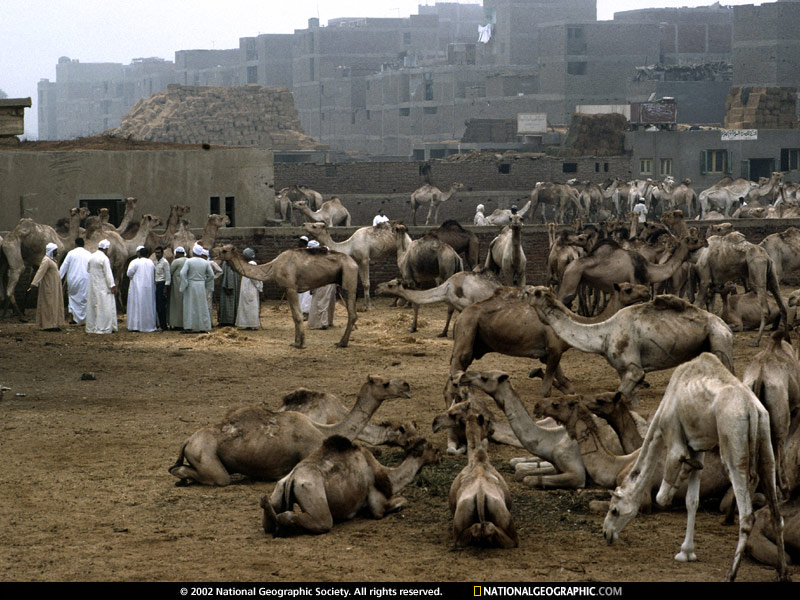

The African Darb al-Arba`īn and its Final Station: Imbāba’s Camel Market

“A trip that bestows upon you and another that takes out of your pocket… and a trip that shows you the flaws of a companion compared to your own” one of the songs of the caravans travelling along Darb Al-Arba`īn. The historical legends associated with the name of Imbāba do not stop here. One of the most important legends is the route for trading and religious proselytizing, known as “Darb Al-Arba`īn (the path of forty)”. This is the old road connecting Darfur (in Sudan) to Imbāba. It was formed over hundreds of years and travelled by traders selling camels and goods, back and forth to Egypt and the camel market in Imbāba. The camel market was a big vacant plot of land where camels from Ethiopia and Sudan came to be sold in Imbāba each year. It has been said that the name Imbāba is a distortion of the original name “Nababa”, a name given to it by those coming from the African south which in Amharic (Ethiopian language) means the Egyptian doum palm. Popular accounts tell us that Darb Al-Arba`īn played an important religious role in spreading the Sufi orders and it was said that it was called Darb Al-Arba`īn because it witnessed the birth and dissemination of forty Sufi sects. Others think its name more likely comes from the forty-day trip, which was the duration of the desert trek from central Sudan to Imbāba (although some accounts state that it was to Asyūṭ or Drau in Upper Egypt). The remains of Darb Al-Arba`īn still cut across Egypt’s Western Desert between Asyūṭ and Dakhla oasis, and there are also remains of it in Sudan. However, many people are unaware of its history and the popular mythology associated with it.

The camel market and the neighboring slaughterhouse continued to operate until the early nineties, supplying camel meat to the different areas of Cairo and to the governorates as well. There is a 1989 article in New York Times that describes – according to one of the camel merchants – the 40 day trip from Fasher in Western Sudan to the heart of Cairo; the author states that the market continued to be one of the biggest markets in Africa and the Middle East until very recently.

Contemporary Imbāba beginning to take shape: The building of a bridge across the Nile links the rural center to the capital.

Over the centuries, Imbāba has continued to develop. Until the end of the nineteenth century, Imbāba was not just a small village like the ones surrounding it, but a rural center whose size was close to that of Giza, which had become the heart of urban areas on the west bank. Imbāba encompassed within its scope several adjacent small villages and farms, among them Kafr al Sheikh Ismaīl, Tāg al-Dowal, Kafr al-Shawām, and Mīt Kardak.

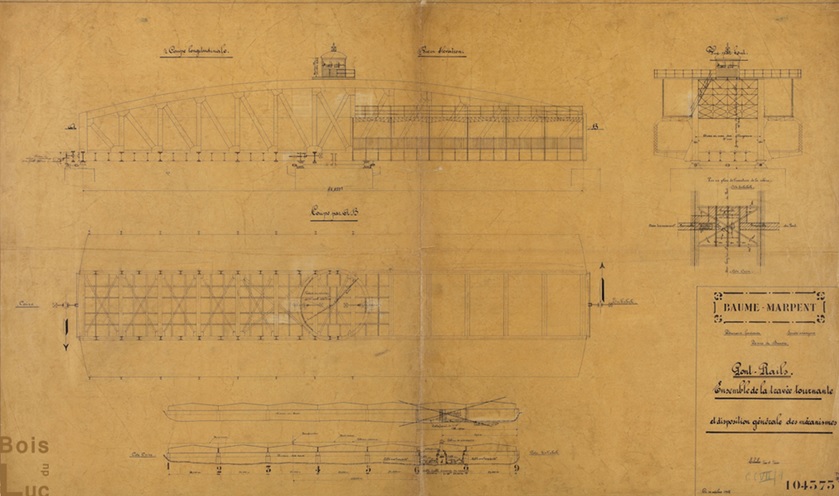

Over time, Imbāba acquired a greater importance if compared to villages of the western bank. In 1890, the first steps were taken to turn this village to one of the stations of the Upper Egyptian train line. A railway bridge was constructed coming from the Giza train station, crossing the Nile to reach the Misr station in the heart of Cairo on the eastern bank. Both the bridge and the station were named Imbāba after the village. In 1913 the railway authorities decided to build a new bridge that would accommodate bigger loads and higher traffic density. It was designed to accommodate two railway tracks, two paved roads for cars, and a pedestrian pathway on either side as well. This was a quantum leap, facilitating access to Imbāba from urban Cairo, encouraging the movement of people and goods back and forth, in preparation for its urbanization. A French contractor was tasked with to building the new bridge; he started the construction at a distance of 35 meters north of the old bridge, which continued to function in the meantime.

Construction stopped during World War I (1914-1918) then resumed, finishing in 1925. It replaced the old bridge which was then dismantled and moved. Subsequently, some of its parts were used in the construction of a bridge in the city of Damietta.

A map from the beginning of the twentieth century showing the village of Imbāba which encompasses the villages of Kafr al Sheikh Ismaīl, Tāg al-Dowal, Kafr al-Shawām, and Mīt Kardak, also the police department (station) in the same current location, and Imbāba train station next to the railway extending across the Imbāba bridge. The map of Cairo, Land Registry Department, 1920 source: Egyptian Geographical Society

The Imbāba Bridge was the first and only swing bridge that was electrically operated among a total of 41 bridges crossing the Nile in various areas of Egypt in 1937, according to a Military Report on Egypt for the British Army in the same year. From this report it is also apparent that Imbāba was considered one of the most central and important region of Egypt at the time; it is one of the 11 regions that had road maintenance units, the others were distributed throughout Egypt from its north to its south. A reservoir was built there to pump water to the rest of the west bank of the Nile, in addition to the Giza Waterworks. The main telecommunications trunk line from Upper Egypt passed across its bridge into Cairo.

As we will see from the subsequent development of Imbāba, this bridge played a fundamental role in changing the nature of the area and transforming it from a rural center to a modern city, bearing the dreams and aspirations of the state and its urban planners.

Imbāba Bridge photographed by one of World War II soldiers (1941), published by his daughter in her blog

The movable part of Imbāba Bridge when open, (no date)

Imbāba Bridge, a diagram of the movable part of the bridge

The riverside of art and recreation for Cairo’s dignitaries, politicians and the wealthy

During this period, the Imbāba corniche, especially the Kit Kāt area, was famous for its house-boats and nightclubs which played an important role in the artistic and indeed the political life in Egypt, especially in the 1930s and 1940s. These nightclubs were an important venue for dignitaries, members of the royal family and British Army soldiers. Within these special places they could spend the evenings, have fun, and carry out deals outside the scope of the propriety and rigorousness which governed their transactions at their places in Cairo. The most famous of these nightclubs and the one mentioned most in the history of that period was the Kit Kāt nightclub, which had survived for many years. It is said that it was built at the time of the French Campaign at the heart of the area currently called the Kit Kāt Square. This famous club witnessed the rise of many famous actors, singers and belly dancers such as Badī`a Maṣabnī, the most famous actress of her time. After her came Tahiyya Karioka, Na`īma `Akef and others. It was also a witness to sensational stories of espionage and major political conspiracies. The most famous of these is the story of the belly dancer Hikmat Fahmī, who had danced in front of Hitler in Germany. Her relationship with the British soldiers in the Kit Kāt nightclub had made her eligible to be commissioned to spy on the Allied forces in favor of Nazi Germany. The tradition of artists owning house-boats on the Kit Kāt Corniche continued for several decades, having been the scene of a boisterous social life filled with parties, meetings with friends as well as the birth of many of the artistic innovations that we have today.

Industrial building in the rural suburbs on the outskirts of the capital

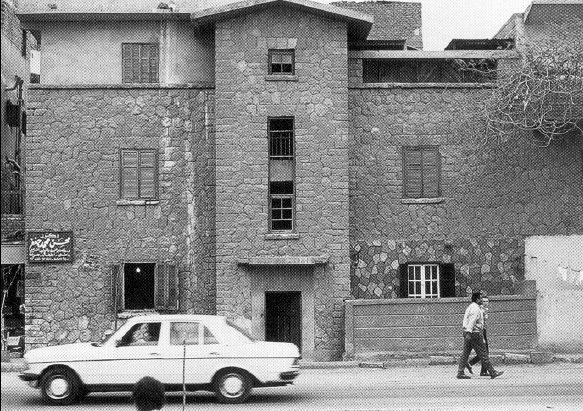

The phase of industrial building in Imbāba began at the same time – the beginning of the twentieth century –with the flourishing and booming of industries in the 1930s. This is contrary to the popular assumption that industrial building in Imbāba was linked to the reign of Gamāl `Abd al-Nāṣir. Just by looking at a map of Cairo in 1930, we can see there were already a number of factories and an even larger number of brickyards occuping Imbāba. By investigating and researching the list of factories that were built in the late 1930s and 1940s, we find that many of these important industrial factories had specifically been built in Imbāba, as it was an emerging industrial zone on the outskirts of the capital. At that time, industry was a hot issue on the national policy agenda; legislation was drafted for it, and National Assembly sessions and meetings of political parties, major capitalists, and property owners were devoted to discussing it (Beinin and Lockman, 1998.) The interest in building large, modern factories in that period was not limited solely to politicians, who promoted industry as a pillar for national independence, or to capitalists who merely wanted to invest in a new promising field. It had also become an area of competition between the most prominent architects and structural engineers at the time, who were specialized in design and construction. Industrial buildings allow more room for the adoption of modernist architectural styles. With their abstract styling, simple lines and state of the art methods of construction, these types of designs had prevailed in Europe (where most these professionals had received their education and training) and had become part of the architectural identity of that era. (Bodenstein, 2010)

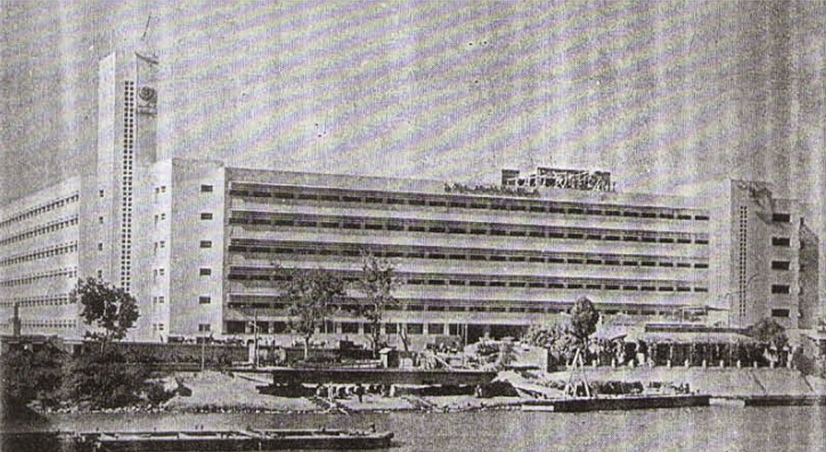

The building of Anglo – Egyptian Motors in Imbāba, designed by architect Maḥmūd Riād, 1937

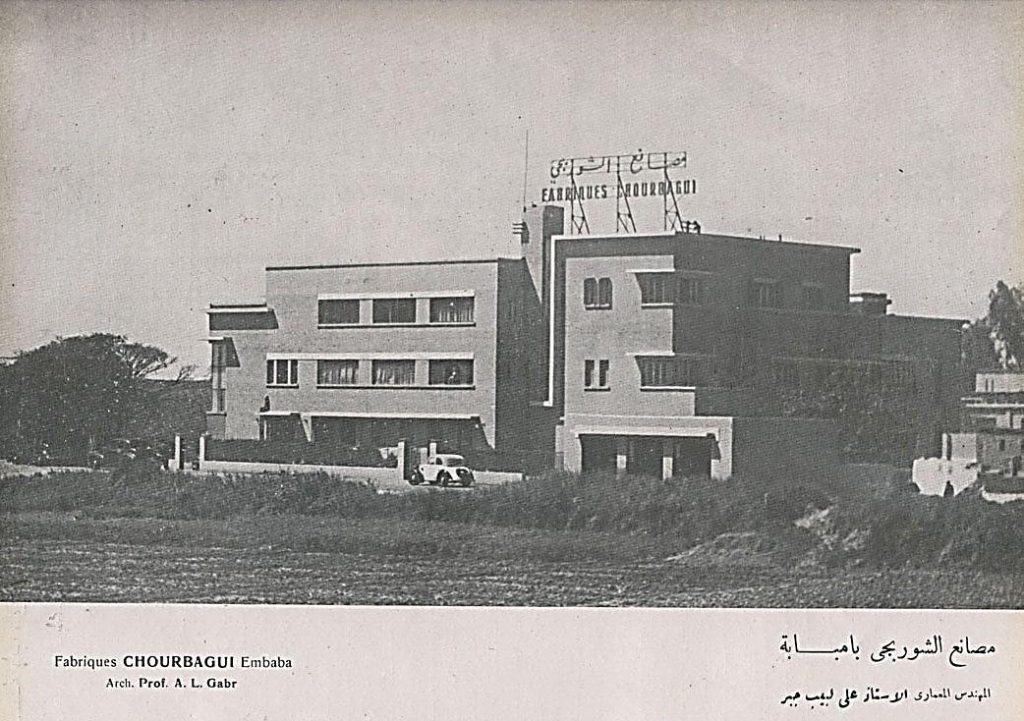

Imbāba, like other industrial areas, acquired a number of these important buildings. For example, the Anglo–Egyptian Motors Company, designed in 1937 by the architect Maḥmūd Riād. He was the same architect who had designed the NDP building on the opposite Corniche. The building was later burnt down, and is being demolished at the time of writing this article. Also among them is the Chourbagui Textile Factory – the “King of fabrics” according to the expression used by the press of that era – which was designed by architect `Alī Labīb Gabr in 1940. This building was of such significance that the prominent specialist publication “al-`Emara (architecture)”, 4 devoted an entire issue to review the design of the plant and its facilities as an example of “the ideal modern factory”. The article explained the advantages of the modern production lines, the large halls and the methods of construction used (Reynolds, 2012). In the following years, the Chourbagui factory in Imbāba continued to be one of the largest and most important factories of the period. It was famous for the important role played by its workers in the Egyptian labor movement and the major sit-in that Imbāba witnessed in the 1950s5. The Chourbagui factory remains in operation to this day and is one of the few remaining factories in Imbāba following the sale of most of the other factories, their demolition and the use of their land for other purposes.

Chourbagui Factory, Imbāba branch, designed by the architect Alī Labīb Gabr, Pioneer Egyptian Architects, Shaymaa `Ashūr 2012

During subsequent decades, Imbāba experienced wholesale relocation of government owned industrial establishments from Būlāq to the opposite bank. The most important step in this relocation was the construction of the new government Printing Press on an area of 35,000 m2. Architect Alī Labīb Gabr was commissioned to design it in 1956, and it was officially moved from Būlāq Abū al-`Ela in 1973. Furthermore, the Maritime Shipyard, founded by Moḥamed Alī Pasha in 1812 on the Būlāq river bank for building warships, continued in operation for centuries until it was moved to Imbāba in 1967.

In addition to these major projects, which are landmarks in the history of Egyptian industry and architecture, Imbāba had a large number of small and medium-sized industrial establishments. For this reason, it was cited in several studies about that period as one of the emerging industrial areas. In the 1960s, new factories in Imbāba and other industrial areas continued to be built in large numbers, especially considering the production of electricity by the High Dam and the increased extraction of natural energy resources like oil and gas from the Red Sea, the Delta and the Mediterranean Sea. These provided the power for the government’s ambitious national project for an industrial renaissance (Bodenstein, 2010). Until the present day, some of these industrial factories or their empty plots, once they had ceased to operate and were demolished, continue as famous landmarks in Imbāba. Prominent examples are The Chairs factory, the Sugar factory, the Chourbagui Factory, the shipyard, the Printing Press, the Grain Silos and others.

The laborers’ housing in Imbāba, an urban seed in the heart of the countryside

In the context of booming industrial projects in Imbāba in the 40s, 50s and beyond, it is logical to expect the emergence of major housing projects to accommodate the workers arriving in the area. But as we follow the story of “the Laborers’ Town” from the beginning, we discover that the birth of the idea dates back to the 1920s. The purpose was not to house the community of Imbāba’s laborers, which had not yet materialized, but it was a part of a larger project to reshape the Būlāq district, the most crowded district in Cairo at the time – according to an official statistical study – (Volait, 2001), and to move a section of the population that, together with its poor district, troubled officials and those interested in urban planning. The reason for this plan was that Būlāq did not match their criteria for a historical Cairo, such as the areas of Fatimid Cairo, and was not up to being part of the prestigious, twentieth century Cairo with its (Khedive/Ismail) European planning such as the Downtown and Heliopolis.

This all started when the Egyptian planner Engineer Sabrī Maḥbūb, who had been educated and trained as a city planner in Britain, took over the Organization Bureau in the Egyptian government. He designed, for the first time, the master plan for the modern city of Cairo, which had involved, among other planning visions and proposals, the re-planning of the Būlāq district. He described the district in his study “Notes About Cairo”, as “the vilest of slums” and described its inhabitants as “the most degenerate class of inhabitants, hordes of beggars and vagrants, intermingling with a large number of workers, artisans and so forth” (as mentioned in Volait, 2001). This was how Maḥbūb saw the demographics of the first urban community he proposed to establish in Imbāba. It is quite likely that Imbāba itself and the indigenous inhabitants of the village did not receive Maḥbūb’s attention as it was nothing but a rural area on the outskirts of Cairo. The plan for the new Būlāq district was to demolish and rebuild all the streets and buildings, and to transfer the government industries such as the railway workshops, government printing press and others, along with the residents working in them, to a new town that would be established especially for them in Imbāba. This would afford the planners an opportunity to dislodge the existing physical structures of Būlāq, with its narrow streets and high population density and replace it with elegant ones with wider streets and larger public spaces (Volait, 2001). This reflects to a large extent, the situation today where the demolition of slums, and the relocation of residents to new towns at the outskirts of the city continues to be the modus operandi.

The plan also included the proposed urbanization of the west bank facing the capital, i.e. Giza and Imbāba, and all that lies in between them to build a new city that was dubbed by the media of the 1930s “al-Madina al-Fu’adiyya” after King Fu’ad, however, it was never built. The plan additionally included the construction of social housing projects, especially for laborers and various junior public servants, many of which were implemented. According to a detailed study that Maḥbūb later annexed to the plan, he proposed building a modern, planned town that would accommodate 5,000 laborers and their families, with funding from the state, and moving the residents and industries of Būlāq to this area. He chose its location in Imbāba on the opposite bank west of the Nile, which was linked to the northern part of Cairo through the Imbāba Bridge that facilitated the movement for pedestrians, vehicles and trains. Maḥbūb’s plan was never implemented at the time for a variety of reasons (for more details see Volait, 2001).

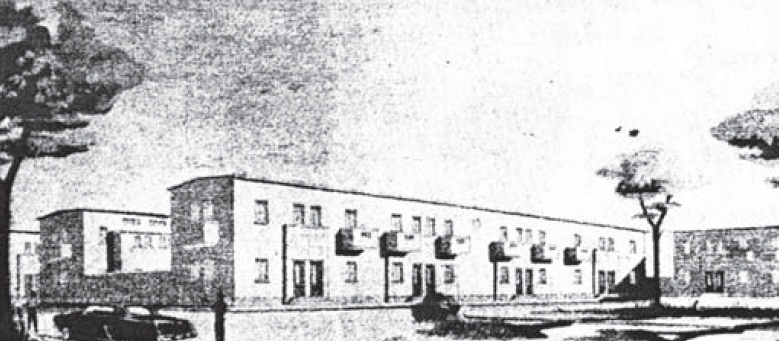

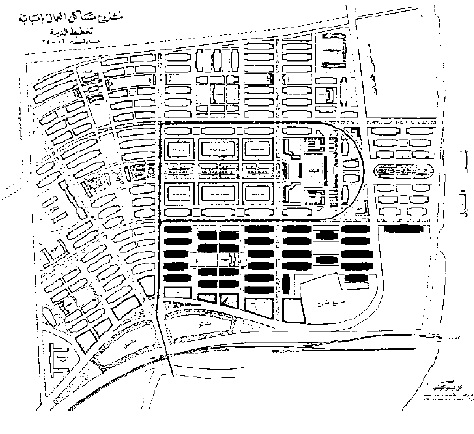

The initial visualization for the western bank town in the twenties of the twentieth century, Maḥbūb (Maḥmūd Sabrī Maḥbūb1934 – 1935) Source: Volait 2001

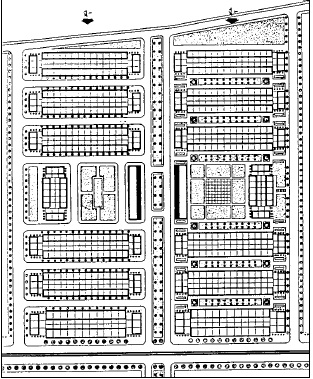

After nearly two decades and after Maḥbūb’s was no longer part of the project, the laborer’s town was finally constructed in conjunction with increasing laborers’ housing projects – both governmental and private. It was constructed next to Imbāba’s historic villages on its agricultural land, at the same spot, north of Imbāba Bridge and of almost the same size that Maḥbūb had suggested. Būlāq remained largely as it was, only later relocating some residents, the printing press and the shipyard workers to the new town. Engineer `Alī Melīgī Mass`ūd was assigned to plan the city in 1946 in his capacity as the director of the City Planning Bureau in the Municipalities and Local Councils Office. He was a member of the British Royal Institute for Town Planning – which showed that the European, and especially British, vision in urban planning was preferred by the Egyptian government at the time. The implementation of the plan for the “laborers’ housing” project started on an area of 1.4 km2 of agricultural land. The government also commissioned specialists – Maḥmūd Riad and Aḥmed Ḥussein to write the report “The Housing of Citizens with Low Income”, which was published in 1949 – to determine the value of rents suitable for the Egyptian working class (Volait, 2005). All this was in conjunction with the formulation and approval of the first law for State Subsidized Housing in Egypt, “Law No. 206 year 1951 concerning Public Housing” 6 (Sims, 2012) This sheds light on the importance of the social housing issue, specifically the model of the laborers’ town in Imbāba at that time, and how it took the lead in the political agenda in a number of ways.

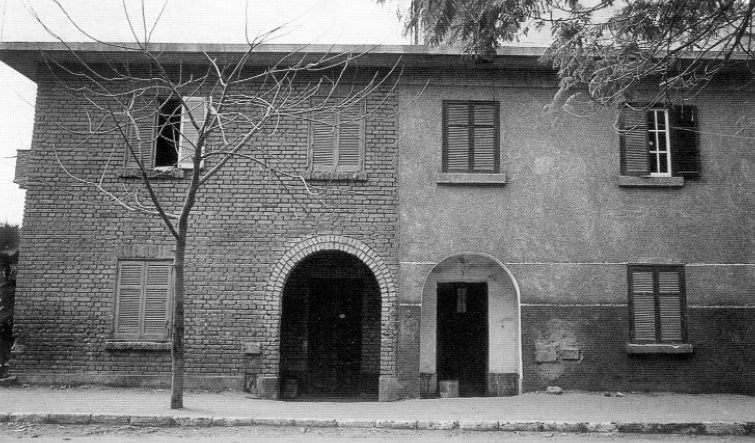

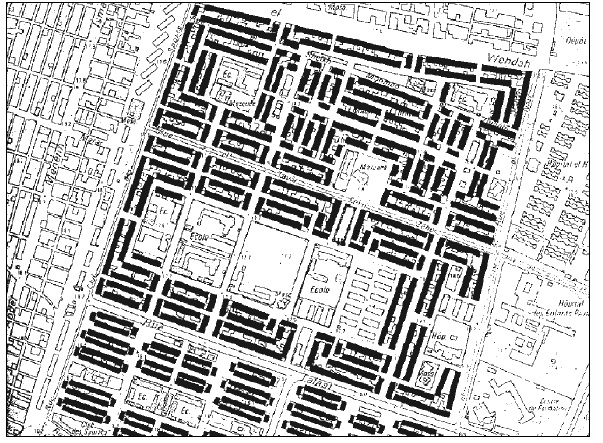

Mass`ūd designed the new town with a network of wide, uniform streets, interspersed with green areas. He allocated river buses and a tramway line to serve the town, and devoted the town center for services and important establishments such as a hospital, schools, marketplace, cinema, a children’s park and parks in general. Mass`ūd was also keen to devote some of the passages for pedestrians only. 75% of the housing was designed to accommodate one family with a unit having two floors and a back garden. The remaining 25% were also two floors, however, each floor was divided into two apartments. The buildings were close to each other (terraced) and had a balcony and a back garden (townhouse), and their façades varied between stone, brick, and lime. It is clear that Mass`ūd’s designs were influenced by the British model of traditional working class housing of an earlier period (Volait, 2005).

The first phase was completed in 1950, and it included 1106 housing units out of a total of 6000 units that had been planned. The units were delivered, and the laborers got their houses with permanent contracts. The value of the rent was determined by the cost of construction, a unit’s spatial dimensions, and its location. It is worth mentioning that some of the current residents of the laborers’ town have the documents with which their parents received their homes in 1951. Later, those units became the family homes and more than one floor was built without authorization to accommodate a growing family and the needs of the children and their new families.

Imbāba is a town now, an industrial town that attracts residents and is capable of expanding

The building work of the “laborer’s housing” came to a standstill in 1952. In fact, the project of the 6000 units that Mass`ūd had designed, and Maḥbūb had developed was never completed – at least theoretically. The project ended after its first phase was completed. There is nothing in the available literature that indicates a direct relationship between the abandonment of this promising project and the critical political situation during that period. However, after the exceptional political developments during the subsequent two years, in 1954 the state began to build a new town for the same purpose – housing laborers and junior public officials – at the site which had been assigned for the project’s second phase, but with a new plan and under under the new name “Madinat al-Taḥrir”. The construction continued in Madinat al-Taḥrir in the following years. Its plan was even replicated in two similar projects in Ḥilwān and Ḥilmiyyet al-Zaytūn. More than 4,000 housing units were built in the three areas in the period between 1954 and 1958. These were the last major subsidized social housing projects, designed in accordance with the concept of a private residence for individuals or families. Those houses resembled middle class villas, which had a private entrance, a back garden and the potential of vertical expansion for the family in the future. After 1960 the subsidized housing policy changed completely; multi-story apartment buildings are designed to accommodate multiple families became the conventional model of laborers’ housing and continues to be to this day (Volait, 2001).

Some turn a blind eye to the possibility of a connection between the political decision to abandon the original plan and build a new town to be called “al-Taḥrir (liberation)” after the Free Officers deposed King Fārūk and declared the Republic, and the customary desire of Egyptian political systems to inaugurate major projects to be attributed fully to them rather than being associated with the efforts of a former regime, to serve as a testament to the stability of their reign and their dedication to development efforts.

Several major projects followed the Laborers and al-Taḥrir towns within Imbāba, among them Madinat al-Sādāt, and Arḍ al-Game`iyya Housing. Some of those were governmental projects and others were private, but all had been planned, were official, and were created in accordance with the government’s visions for housing and development, or at least with its consent.

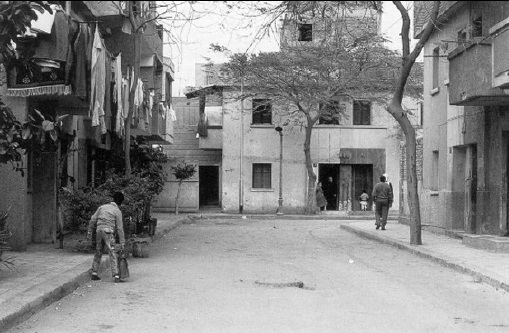

The village, the Town and what Lies in between: Unauthorized Extensions of Construction

The official extensions of the town, planned and built by the government, were not the only urban development activities in Imbāba as there were various other forms of unauthorized urban extensions in the area. One of the informal extensions was associated with the official laborers’ towns. Two researchers from the Institute for Urban Transformation Studies (ETH Studio Basel) noticed, in an aerial photograph of Imbāba from the 1950s, haphazardly planned houses adjacent to the houses of the Laborers’ town. The researchers believe that those were originally built as temporary housing for construction workers in the Laborers’ town and then Al-Taḥrir town during the late 1940s and 1950s. They then settled there permanently. The researchers state that this was the first unauthorized urban construction in Imbāba (Peronnet and Rodemeier, 2010).

An aerial photograph from the 1950s showing unauthorized houses which were said to be those of the workers in the project of “Laborers’ Housing”

The completely unplanned villages– which reflect the nature of construction in the Egyptian countryside– continued to grow and expand, following the same inherited and unauthorized patterns. In spite of the construction and expansion of the planned town, the villages remained clustered to the north of the railway line and the Imbāba Bridge. This formidable wall continued to separate the historic villages of Imbāba from its modern laborers’ towns. Government plans did not involve the demolition of old villages or the relocation of their residents to the new urban areas with their modern residential blocks, gardens and wide streets. It is obvious the plans did not take into account the needs of those people, nor the far-reaching impacts those new developments will have.

The extraction of topsoil from agricultural land, which was the source of income for its residents, continued unabated. Due to governmental inaction, the old rural houses south of the bridge remained in their state, towns continued to be constructed one after another adjacent to these villages with their traditional, narrow winding streets and irregular buildings. With population growth, changes in the economic activities of the village residents, and general socio-cultural changes, successive generations of the residents demolished their old rural houses. Those consisted of a ground floor with an internal courtyard surrounded by rooms where the children and their families lived. After demolishing their old homes, they divided the land of the family house into several plots and each built a separate house for themselves and their family, then for the families of their children and grandchildren later on. The current residents of old Imbāba describe this change simply: “each one can close one’s own door”, referring to the newly created need for privacy among the members of a family, which had been developping in the Egyptian rural communities more generally. With time those houses reached the height of three or four floors, overlooking the same narrow streets, the flats now lacking in sunlight and ventilation.

As a consequence of the increasesing price of land next to or within the urbanized areas and the changing nature of the economic activities, residents increasingly sought to sell agricultural land, parcel and build on it on an unauthorized basis. The continued government activities in extracting topsoil from agricultural land, and the expansion in the urbanization of Giza – which now includes large, upscale areas such as al Awqāf town (currently al-Mohandisīn) – adjacent to Imbāba has exacerbated this trend driving further unregulated urbanization. The current urban fabric reflects the agricultural divisions that once were. For example, the old canals were filled in to become the main streets between the houses. As the inhabitants did not build those new neighborhoods according to a designed urban plan, the provision of appropriate service areas, green spaces, or suitably wide public spaces that could serve as transportation hubs and for other purposes, were not taken into consideration.

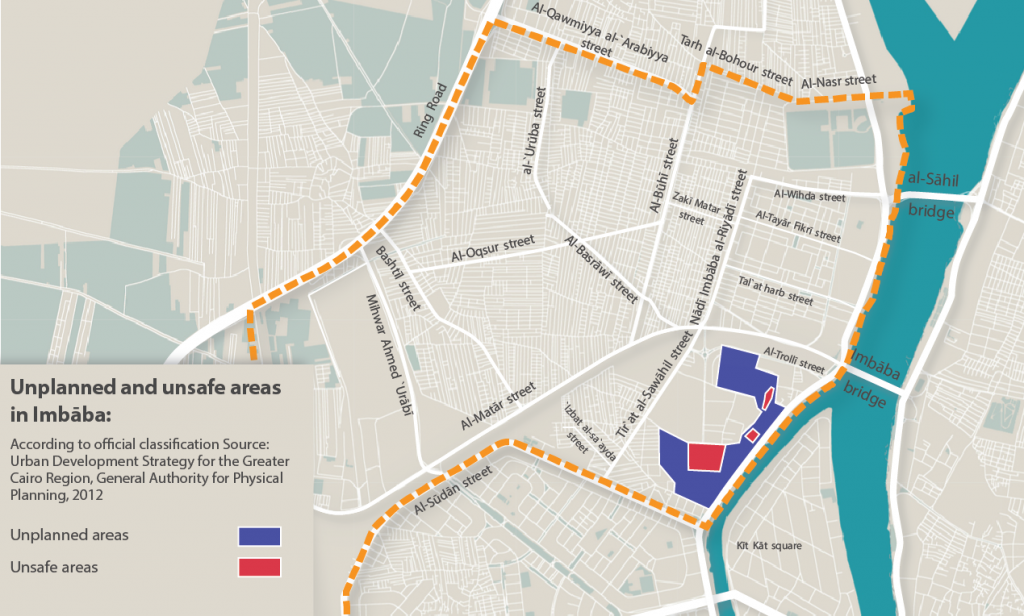

Imbāba was not the only area undergoing this kind of development. The type of unauthorized construction and urbanization had become the most accommodating for population growth in the Greater Cairo Region, where the proportion of residents in informal areas rose from about 15% of the population in 1960 to 64% in 2009, (Sims, 2012). Government planning efforts were not sufficient, effective or responsive enough to accommodate the population growth or stem the tide of informal settlement.

What was once agricultural land on the outskirts of Imbāba has now become the center of Imbāba and entire residential areas have now grown on those plots. The residents of those informal areas within Imbāba are diverse. While some quarters were formed of migrants from various governorates or Cairenes looking for a house with suitable rent, other areas were more distinctive in their formation. Some are entirely made up of families or tribes from Upper Egypt who came to Imbāba in a mass exodus that lasted for years. They formed their own societies, which imposed its characteristics over the place, so the new settlements were named after them and were formed according to their norms. Some of them still exist today such as `Izbat al-Ṣa`āyda, near Kīt Kāt square. It was settled in the 1940s and 1950s by migrants from Upper Egypt, who belonged to large and famous families, such as al-Nowayta and al-Fagar from Qinā Governorate. Ostensibly, the first family member who went to Cairo settled and worked in Zamālik, later buying vast areas of agricultural land in Imbāba and bringing relatives to cultivate the land and live there. He became their mayor, and more of his relatives came to Imbāba, and built temporary modest houses – huts made from palm leaves. Over time, they settled down and developed their residential colony with the help of a building contractor who divided the land into streets and constucted buildings that had apartments and shops. It was called `Izbat al-Ṣa`āyda (Upper Egyptians estate), and the area still carries the same names amongst its residents.

Other areas of Imbāba were formed entirely by migrant communities similar to `Izbat al-Ṣa`āyda. Some of them settled permenently, while others came and left, no longer existent in Imbāba except in memory. One particular example was the “rubbish collectors” from Aṣyūṭ, who occupied an area of land in Imbāba for about 40 years, during the period between 1930 and 1970. They lived in al-Baṣrawī area in al-Munīra al-Gharbiyya, and collected rubbish from all of Greater Cairo. They sorted it, raised pigs and sheep around their informally built houses, and set up a community according to the functional needs and the financial abilities of its members. The contemporary residents of Imbāba remember them with some disdain, seeing their community as nothing but people who raised “impure” pigs, the area around them reeking with the smell of rubbish. The colony of rubbish collectors continued to be a part of Imbāba until they were confronted with an eviction ultimatum issued by the Governor of Cairo in the late 1960s, after which they were moved to the bottom of al-Muqaṭṭam, a hill allocated to them through a presidential decree from Gamāl `Abdel Nāṣṣer, “Munsha`at Nāṣṣer” as old rubbish collectors recount.

Thye construction of the ring road around Imbāba at the end of the 1980s, encouraged the encroachment upon the agricultural lands remaining in Imbāba, as it did in other areas. Today, almost no agricultural lands remain within the scope of Imbāba. The unauthorized construction of high-rise residential towers around the ring road extended to the Bashtīl area on the other side of the road, which, until recently, was a village affiliated to the rural Imbāba municipality – which no longer exists administratively. What happened was an expected – or rather planned – result of the construction of the ring road. With an attractive location on the sides of the most important highway around Greater Cairo the value of the land increased, making the revenue from building on it and investing in its real estate, especially in the light of a continuing housing problem, much more profitable than cultivating it. In addition, the problems faced by the farmers in Imbāba made cultivation seem more like a struggle than an economic activity to earn a living. Again, Imbāba was not unique in this development, as the rate of urbanization on the outskirts of Greater Cairo increased almost three fold after the construction of the ring road (Piffero, 2009). The “Long Term Development Master Plan” prepared by “Ile de France” Institute and approved by Hosni Mubarak in 1983 – proposed the construction of the Ring Road as a belt around Cairo and considered it “the most urgent of measures” to limit the urban sprawl (Dorman, 2007). However, the ring road achieved the opposite, despite the provisions made in the plan as to not to “encourage urban growth on the agricultural areas,” and support the construction of other informal areas along the length of the road, especially arable land on the outskirts of Giza (Raymond, 2000) . This proves the lacking vision of the plan which did not take into account the economic and social conditions, and the total lack of local justice across the country that led to the creation of those settlements. There is no need to highlight the failure of these planning provisions in achieving their goals as they have clearly only succeeded in achieving the exact opposite result, just as we have seen in the mini model of Imbāba.

Islamic Emirate in Imbāba

Political Islamist groups have a long history in modern Imbāba, starting with the Muslim Brotherhood, the Salafis, al-Tablīgh wa al-Da`wa and ending with al-Gama`a al-Islāmiah. The most violent group, al-Gama`a al-Islāmiah had the greatest influence in urban Imbāba, making its name synonomous with controversy and conflict. Here we will describe what we have come to learn about it.

Al-Gama`a al-Islāmiah decided to colonize the heart of the capital and grow there, in al-Munīra al-Gharbiyya, west of Imbāba and Greater Cairo, and fight the state for control over the area. According to Patrick Haenni, the struggle over the public life in al-Munīra al-Gharbiyya was between the union of “al-Okhwa fi Allah (brothers in God),” – which the Islamic groups founded, and mobilized the society around – and the union of blood in the form of “tribes and families” and lastly unions formed around geographical origins which consisted of “people from the same governorate” (Haenni, 2009). He demonstrates how community leaders in that period were replaced to reflect the new balance of power. He also reflects on the role of the state and its authority in that conflict – which was sometimes overt and more often covert. In addition to questioning how this conflict related to the state and the citizen, and how these conflicting relationships changed the structure of daily life in Imbāba.

The influence of the Islamic groups was very apparent in the way streets and mosques were named. “Al-Īmān Bellah (Belief in God)”, “al-Ikhlās (Loyalty)”, “El Da`wa (The Advocacy)”, and “al-I`timād (Reliance)” were not conventional names for mosques in Upper Egypt or anywhere else. Traditionally, the mosques were named after the persons who had built them, one of the Holy men of God, historical Islamic symbols or community leaders.Similarily, streets were given names such as “al-I`timād Street”, “al-Gihad Street (Holy War)”, and “al-Saḥwa Street (Awakening)”. The goal was not just the Islamization of urban space, but also to distinguish them from those built by the dominant Upper Egyptian families (Haenni, 2009). The political Islamic groups gained popularity and support, which many link to the services they offered to citizens who were abandoned by the state and then found themselves in desperate need of basic services. For example, Anṣār al-Sunna al- Muhammadiya built a mosque and two schools in Imbāba. Additionally, they provided medical care and implemented social programs in an area of al-Munīra al-Gharbiyya. This helped to increase their popularity and the residents’ confidence in them (Bayat, 2009).

The relationship between apolitical residents and the Islamic groups was not always harmonious as charity work, economic aid, reconstruction and religious advocacy were not the only aspects of the incursion of Islamic power into the region. With the expansion of their authority several manifestations of violence emerged in order to exert control over the public domain in Imbāba. The groups even recruited well-built young people who have a history of bullying and criminality to deploy in street wars. Weddings became a key target for Islamist violence in Imbāba. It was a common sight to see members with chains and blade weapons attacking street wedding celebrations in which alcohol, hashish and belly dancers were traditional. The inhabitants of Imbāba started to become suspicious of the nature of those groups, who had previously been appreciated because of their religious commitment (Haenni, 2009).

Some of the contemporary residents of Imbāba who bore witness to that time told us that Islamist leaders had so much power and control over some areas that when they planned to hold wedding celebrations – the biggest and most important social event in public life– they needed to go to the police station to get the “permit” – an unauthorized verbal permit – where they would be told that they first had to get Sheikh Gaber’s permission7.

When the 1992 earthquake hit Cairo (the most destructive in the history of modern Cairo) the government’s response was inadequate and their sheer incompetence in rescuing victims became evident. On the other side, the zakat committees in mosques and Islamic groups provided tents, blankets, food and other urgent needs to the affected residents. Naturally, their immediate response to the disaster improved their image among the public and increased their popularity, leading some to claim that this moment of popularity encouraged the Islamists to stand up against the state more directly and clearly (Singerman, 2009).

The proximity of Imbāba to the center of the capital definitely had a chilling effect on the central authorities. Its authority was not being challenged in a remote part in Upper Egypt, but at the heart of a city where it should have full control. According to the security reports, the Ministry of Interior aimed to liquidate what it called the triangle of violence, which is comprised of Asyūṭ, `Ayn Shams, and Imbāba. There are numerous reports about the critical moment that changed the direction of state policy toward the Islamist groups in Imbāba specifically, from ignoring and sometimes even cooperating with them, to what became a fierce confrontation. The media reported that the Islamist group had announced the independence of the region under the name of “The Islamic Emirate of Imbāba”. Researchers claim that international news agencies, particularly Reuters and the Associated Press are the ones who coined this expression. Other reports claimed the spark was a demonstration against the death penalty received by some Islamists during a military trial in Alexandria. It was also alluded that it was the result of the Islamist group showing the banned video of the assassination of Sadat on televisions they had put up in the streets (Singerman, 2009). One or all of these reasons served to enflame a war between the state and political islamist groups in al-Munīra al-Gharbiyya, with its most important manifestation being the siege of Imbāba by security forces in December 1992. This episode has continued to influence the public debate for a long period of time, so much so that it inspired the film makers of “The Blood of a Deer” to produce a film 12 years after the events, inspired by one of the stories of the siege.

The siege of Imbāba as a turning point in urban policies

“Between the 8th and 9th of December 1992, an unknown nieghborhood was transformed into a symbol. Imbāba was besieged by 16,000 security personnel led by 2,000 officers, in one of the biggest security sweeps in the history of Cairo. It brought this informal community into the limelight, where it could no longer be ignored. This community now had a name, and soon it would be the subject of an abundance of descriptions, formal debates, and specialized analyses for determining its geographical borders as described by Eric Dennis (1994) in Singerman ( 2009).

The area was blockaded by bulldozers, police dogs, security vehicles and other equipment – some described them as worthy of a war between two regular armies. Hundreds of area residents were arrested, and a few were killed during a siege that lasted six weeks (Singerman, 2009).

This incident was a significant landmark in the history of state dealings with informal urbanization. The government’s actions aimed at tightening the security over areas considered shelters of their principal political opponents in the 1990s, the followers of the Islamist trend and, the accompanying media discourse established attitudes that molded public awareness and perceptions of these areas. This happened abruptly, even for the residents themselves. This discourse has shaped the national policies and plans regarding informal areas for the past two decades. No longer are they considered peasant areas which threaten the urbanization of the city, they are now areas of violence, extremism and lack of ethics. Up to this day, a discriminatory and provocative discourse exists against the residents of informal areas, which are, for the most part, mainly inhabited by poor people.

On the 1st of May 1993, a few months after the siege, President Husnī Mubārak tasked the government with the immediate implementation of a developmental program for informal areas in all governorates to provide them with important services and facilities. The United States Agency for Development (USAID) had already started to pave streets and develop the drainage system in Imbāba. European NGOs followed suit, implementing various community development projects. In turn, the government announced a five-year national plan to implement development projects in informal areas, from 1993 to 1998 at a cost of 3.8 billion Egyptian pounds. Al-Ahram Weekly reported that until 1996, 127 out of the 527 targeted areas had been fully developed. As expected, al-Munīra al-Gharbiyya in Imbāba received greater funding than any other area in the Greater Cairo Area (where the majority of targeted areas were). Between fiscal years 1992-93 and 1995-96 more than 372 million Egyptian pounds were allocated for the development of al-Munīra al-Gharbiyya alone (Bayat, 2009).

Imbāba had become fertile ground for research and analysis. Research was conducted, and many studies and articles were written about the informal areas, analyzing what had happened in Imbāba and the so-called “phenomenon of informal areas”. This is despite the fact that this pattern of urbanization had existed for decades before. For many segments of society such as people with average income, young people, newly married couples, poor people and immigrants from both urban and rural areas, informal housing is the only option. Imbāba captured the attention of the media, Egyptians intellectuals, specialists in Middle Eastern Studies in Europe and America, international organizations and major financial bodies. Imbāba became al-Munīra al-Gharbiyya, and al-Munīra al-Gharbiyya was Imbāba; the informal Imbāba, the land of poverty, political violence, crime, extremism, ignorance and turmoil. All other facets of Imbāba disappeared from sight for years.

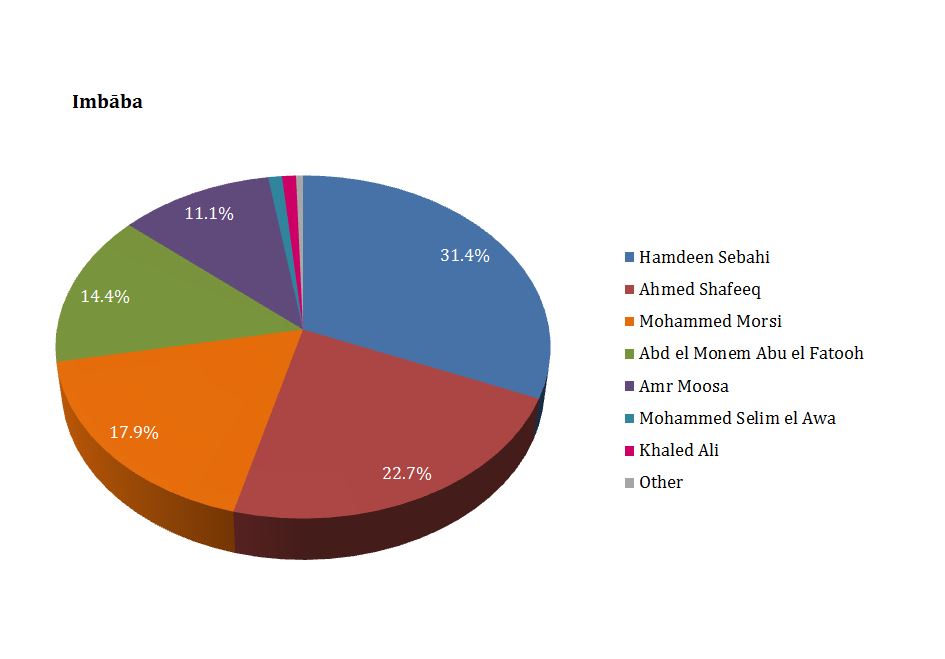

Imbāba experiences open public domain after 2011

We notice that as soon as Imbāba, similar to other districts, experienced relative freedom after January 2011, the diversity of Imbāba’s residents, the differences in their living conditions and their political leanings became apparent and surpassed any generalization, that had been made thus far. Despite the flood of news and events throughout the country, especially in Greater Cairo which took center stage during and after January 2011, Imbāba attracted the spotlight more than once during the past few years. For one, it was renowned as an important starting point for the massive political demonstrations in 2011. The crowds would start out in the streets of Imbāba and meet at several different points, the last and most important of which is Khālid ibn al-Walīd mosque in Kīt Kāt Square, then head to al-Taḥrir Square downtown. Several organizations emerged to defend the rights of Imbāba residents; such as the Imbāba Popular Committee for Defending the Revolution. Electoral conflicts abounded there (as in other places) between different camps. Ironically, Imbāba, which had been branded as an Islamist stonghold, voted dramatically against representatives of political Islam in the 2012 presidential elections. It was said that Islamists left it to go to other areas after having been targeted in it throughout the 1990s. In reality, we do not have much information about the political affiliations of the residents as we cannot list all the organizations and social movements, neither today nor ever, because monitoring such affiliations requires the presence of effective citizen participatory mechanisms that would enable the monitoring of citizens’ attitudes, preferences, and demographic data. All of those directly affect the form of urbanization that takes place, and people’s lives within it.

The results of the first round of the presidential elections 2012 Imbāba election committee.

Source: official website for presidential elections 2012

The past few years have revealed much of the tension bubbling under the surface in Imbāba, manifesting itself in instances of sectarian violence. The most famous and cruelest incidents occurred on the two main streets in Imbāba in May 2011, resulting in 15 deaths, and 242 wounded, according to a report of a human rights organization. Following that, two churches were burnt in Imbāba, namely The Church of Saint Mina and The Church of the Virgin Mary. As a result 190 people were arrested and referred to the supreme military prosecutor’s office for interrogation. The situation necessitated the intervention of the army for the protection of the buildings, as well as the supervision and financing of their repair works carried out by a team of specialized monuments restorers. While those events took on the character of a conflict between religious denominations, the authorities failed to fulfill their duties in containing them and minimizing their losses. Similar to other neighborhoods Imbāba saw violence and conflict between the State and its Islamist opponents after the 30th of June 2013. The incident that had the greatest impact on the shape of surrounding urban area was a bomb explosion in front of the Courts Complex building on the corner of Ter`et al Sawaḥel Street on the 14th of January 2014, which did not result in loss of life, but coincided with the referendum on the new draft of the constitution. The building is still being repaired until today.

An explosion in front of North Giza Court Complex on Sūdan Street, 2014

Source: Al Ahram newspaper

However, in a larger sense we should not focus on the events of political violence, where factors often overlap to create a justification for evacuating the public domain and taking control of it. The significance of those events should not be disproportionately inflated when hundreds of thousands of people go on about their daily lives, spontaneously using public spaces to buy, sell, meet in cafes, and attend weddings, funerals, festivals and other activities in a dynamic area, which is full of both private and informal shops that provide for daily needs, covering almost everything one can imagine in terms of goods and maintenance services.

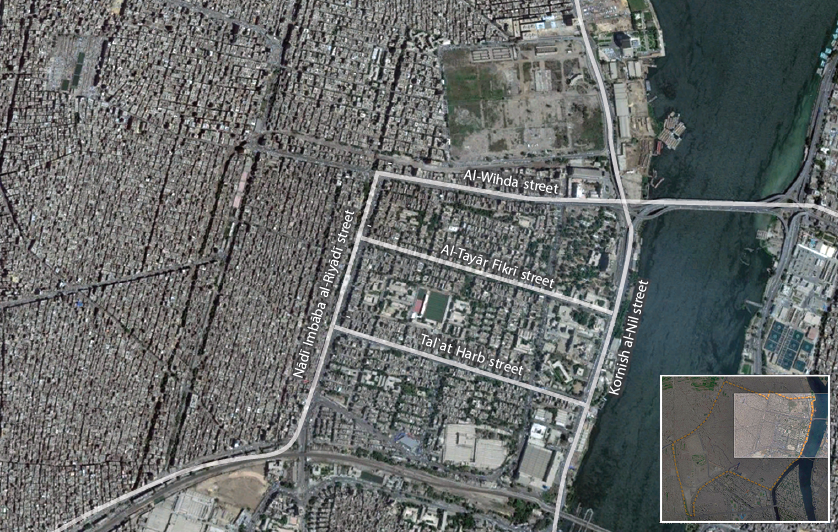

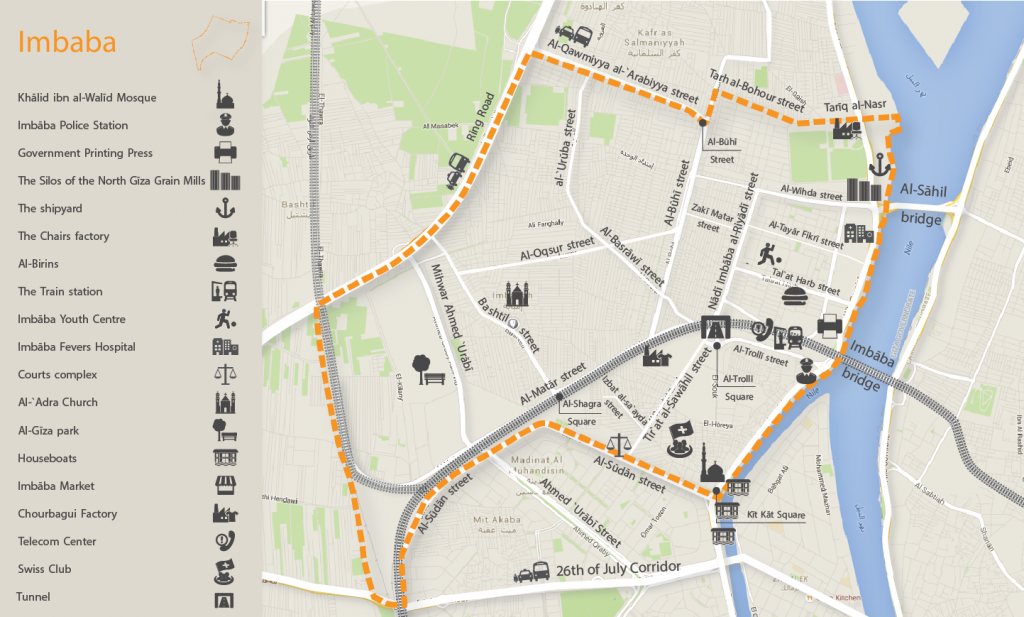

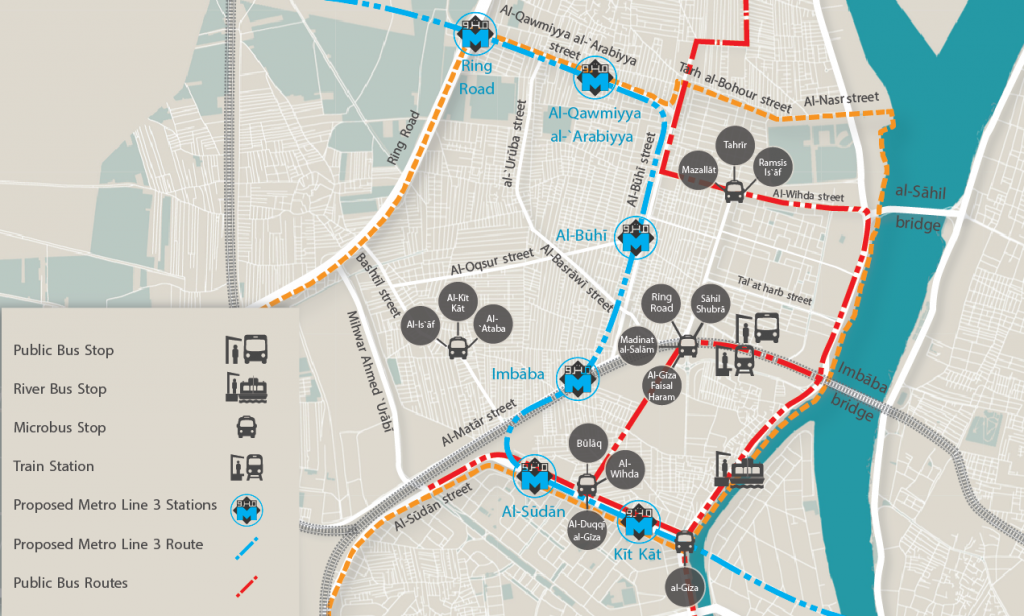

The place and its people

Imbāba today is one of the most densely populated areas, not only in Cairo but in the world. It lies to the north of the capital on Giza governorate’s Nile bank, where the corniche is considered its main façade. For those coming from the south, along al-`Agūza corniche, it can be recognized on arrival by the famous Kīt Kāt Square. Bridges play an important role in connecting Imbāba to the various districts in Cairo governorate; the Imbāba Bridge and al- Saḥel Bridge lead to Būlāq Abū al-`Ela, and from there on to the town center, Old Cairo, and the Ma`ādī Corniche to the south, and Rowḍ al-Farag, al-Saḥel, and Shubrā to the north. Imbāba shares Sūdan Street – one of its main streets – with El Mohandisīn district, and it also shares al-Qawmiyya al-`Arabiyya Street – one of the most important main streets in Imbāba – with al-Warrāq to the north. The ring road connects it to several areas around Greater Cairo by means of microbus routes and stairways that were constructed by the residents themselves.

Imbāba residents are crowded in its buildings which were formed by mixing all the economic and physical strata of the urban and rural areas, planned and unplanned. We find middle-class areas, next to governmental public housing and beside informal slum buildings, just a few residential blocks away from a tower block whose ten or more floors overlook a broad street, and hide less expensive residential buildings lining the narrow streets behind it. In addition to the diversity in its building configuartion, Imbāba is also characterized by the demographic diversity of its inhabitants’ in terms of their origins, their varied social and educational backgrounds, and the economic sectors in which they work. They differ even in their perception of the district they call home, its landmarks which some would consider important while others view indifferently and its problems as those differ from an area to the next. We have identified the differences in perceptions of the residents of the factory workers’ compounds and employees and those living in al-Munīra al-Gharbiyya for example, and how specific stereotypes of “the other” shaped this perception. That is to say, the perceptions of Imbāba’s residents themselves of their district is not homogenous; Imbāba is a large district, everyone often moves within one’s neighbourhood, with no need to visit other areas within Imbāba. Thus, to understand the urbanisation of Imbāba, we will devide it into areas, and try to take a closer look at the nature, diversity and distinctive features of each area8.

The historical villages of Imbāba merge with the housing of Upper Egyptians and the governmental housing in the area bordering al-Mohandisīn and facing the Zamalek Island, separated from it by a branch of the Nile with its famous house-boats.

The area south of Imbāba, confined between the Nile corniche, Sūdān Street and the railway line, is one of the areas that have the clearest geographic boundaries and is home to many of the diversities and contradictions of Imbāba’s physical planning. Its main entrance through the Kīt Kāt Square on the corniche can be recognized by Khālid Ibn al Walīd Mosque, which obscures behind it the old areas of Imbāba, where they have been located for centuries, along the strip parallel to the Nile corniche. They even still keep their historic names: Mīt Kardak, Kafr al Shawām, Tāg al Dowal, Sīdī Isma`īl, and Gizīrat Imbāba. The Nile corniche is considered the most important recreational outlet by many of Imbāba residents; some of them even described the wedding halls and parks along the Nile as “the most important advantages of Imbāba”. Some of the house-boats, although less popular now than they were decades ago, still function as social, cultural and entertainment meeting places, as restaurants or quiet, simple hotels on the Nile.

Khālid Ibn al Walīd mosque, situated in the location previously occupied by the Kīt Kāt Night Club, the square still carries its name, Kīt Kāt Square (Tadamun, 2015)

The Nile corniche from the Kīt Kāt direction has modest residential houses a few stories high, contrary to many other areas where the waterfront is invaded by high rise towers. On the ground floors are grocery stores, car repair workshops and simple crafts shops. (Tadamun, 2015)

House-boats on the Nile in Imbāba; residential houses, wedding halls, restaurants, and simple, quiet hotels (Tadamun, 2015)

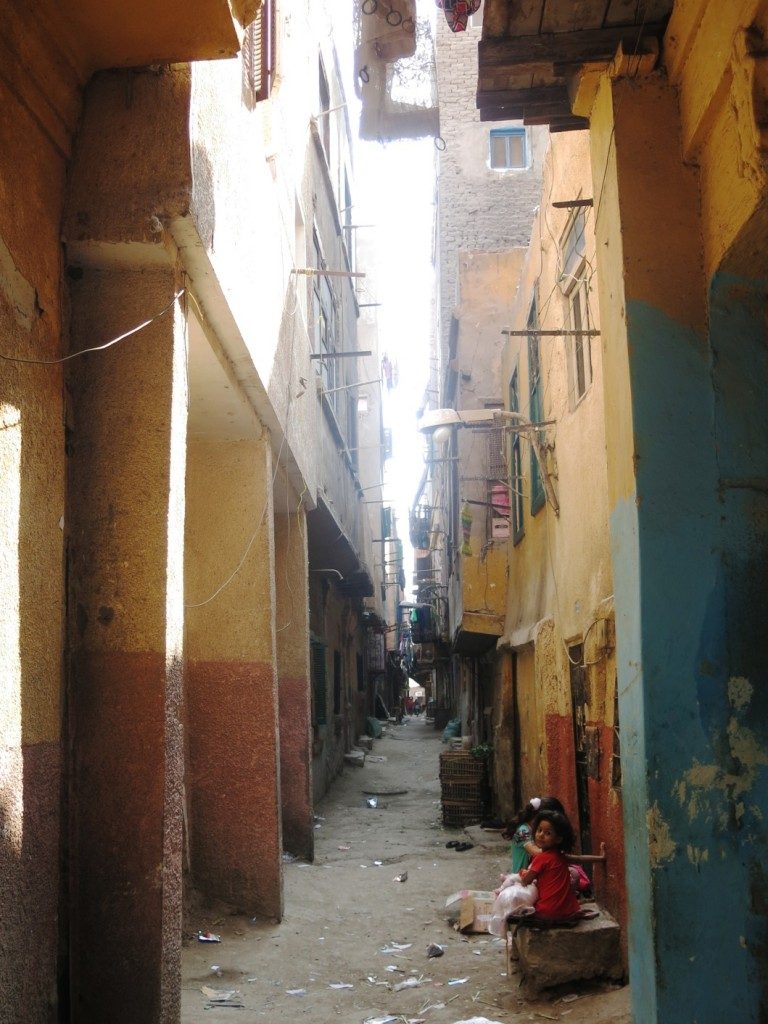

The Nile embankment, beyond the row of residential houses, is occupied by several governmental buildings, the most important of which is Imbāba police station, standing in the same place since it was built in the beginning of last century south of the Imbāba Bridge. Today it resembles a fortress after surrounding it with concrete blocks used to create a wall of protection around sensitive buildings such as police stations, ministries, and the embassies of powerful states. This has become a distinctive modern feature in the streets of Egyptian cities. In front of the police station stands the river-bus station, which is crowded during daytime by large numbers of youths who use the bus to cross to Zamālik. Next to the police station, lies Trolley Street, an important entrance from the corniche which leads us to the heart of Imbāba, running parallel to the railway until it reaches the Trolley Square. This square was the main terminal station of the trolleybus (electric bus) which previously travelled along the streets of Imbāba, but have since been decommisioned. Between the police station and the square we see many distinguishing landmarks such as Imbāba central telephone office, the train station, and a cultural social center for the residents, that has several football fields and billiard tables that the youths in the area rent to spend their leisure time. Behind the police station lies the mosque and dargah (shrine) of Sheik Isma`īl, surrounded by Kafr El-Sheikh Isma`īl and the Imbāba Island areas, which are not much different from the rest of the old areas of Imbāba: narrow streets with old houses built using traditional methods, either out of stone or mud bricks and mortar, and other new ones built out of concrete and red brick. They are for the most part three or four floors high, while the width of the street sometimes does not exceed two meters. The streets are completely devoid of lighting and paving, with the exception of a few streets that the residents illuminate with lanterns hung on the façades of their modest homes. The area also has many deserted houses, which cause several problems for the residents as those houses are in danger of collapsing due to dilapidation and neglect. This would adversely affect neighboring buildings. Additionally, the residents sometimes use the deserted houses as rubbish dumps, which could cause fires that would be difficult to control because the closely packed houses and narrow streets prevents fire engines from reaching the site of the fire. Moreover, the areas of old Imbāba suffer from bigger problems compared to neighboring areas; sometimes the streets flood with sewage water and the residents cannot move around, as the ground becomes muddy. They are sometimes even forced to wade through the sewage water. The demographics also vary; some residents are destitute, or are day laborers in the informal sector, while others own workshops or shops. Also among them there are those working in prestigious professions such as physicians, engineers and lawyers. The residents regard the inherited, strong social relationships between them as a huge advantage; if you are one of the residents of the area, it is impossible not to be known by each and every individual there, they would even know the details of your work, your family life and your relatives. This makes residents feel safe within their area, as they are able to monitor strangers and their movements, and determine whether or not these are to the benefit of the area or otherwise.

The streets of Sidi Ismail, after the residents had demolished their old, rural mud houses, and built in place higher concrete buildings in the same narrow streets. (Tadamun 2015)

Tir’at al-Sawāḥel Street is the main street that passes through this area. It starts at al-Sūdān Street, where the Imbāba courthouse – formally the North Giza courts complex- is situated on the corner, and terminates at the Trolley square on the other end. There are many informal areas on both of its sides, which began as huts of Upper Egyptian migrant families, then developed and expanded to form a group of streets following the same pattern as `Abd al-Na`īm street (`Izbat El Ṣa`āyda) such as al-Ṭanāni, Bayūmi Salām, Tawakol `Asrān and others on the opposite side of the street. The buildings range from four and five stories in height and have been built within a short period of time during the 1950s and 1960s according to the current residents who also claim they were built by the same building contractor, which is the reason they all have the same design, divisions and distribution of rooms. Most of the inhabitants of those houses are the owners themselves or their offspring. The proportion of rented flats in these areas is low, however, there is a small number of tenants with rental contracts according to the new leasing system, who mostly live in newly built houses which reach a height of eight to ten floors. These are still few in number and are located at the edges of the area. The majority of streets in these areas are inhabited by relatives and kinsfolk – that is, individuals coming from the same locality. El Ṭanānī street for example is well known for the presence of a large Nubian community in the area; a single street could be inhabited entirely by the members of one extended Nubian family, with no outsiders. The same applies to the Upper Egyptians who have populated and inherited `Izbat al-Ṣa`āyda. Those areas have a variety of closely associated social classes. They are neither very rich nor too poor, but there is, of course, disparity in income levels as well as the level of educational and cultural backgrounds – which are considered class related issues in Imbāba and in the other regions of Egypt – as well as origins, ethnicities and religions. Speaking with the residents, they talked about tolerance and exemplary coexistence between the various groups. They said that the Upper Egyptians and the Nubians have formed a cohesive, loving society, despite the fact that the members of one ethnic community – whether Nubians or Upper Egyptians – marry only from their own community. They never mix their genealogies and to this day a lot of families take this matter seriously and strictly. They also spoke about the supportive relationships that exist between the wealthier groups and those struggling financially in various situations, as well as the inherited social awareness which forms strong relationships that maintain its cohesion in times of crises. They also told stories about dealings between Muslims and Christians in which sensible words about national unity and coexistence predominate. These areas don’t offer employment opportunities, with the exception of some small projects such as coffee shops, pharmacies, grocery shops, herbalist shops, other sundry shops and workshops. These shops are run by and staffed by their owners, and they do not provide employment opportunities except for a limited number. Most of the residents go to work in other areas in Imbāba or in Greater Cairo generally.

Right: The famous `Abd al-Na`īm Street in `Izbat al-Sa`āyda. Left: One of the side streets in `Izbat al-Sa`āyda area. (Tadamun, 2015)

At the heart of this area, on the right side of Ter`at al-Sawāḥil, the Swiss Club occupies one of the historical palaces, which was most likely built in the first half of the last century. The residents claim that it used to be one of the residences of King Farouk. Years ago it became the premises of the socio-cultural club affiliated to the Swiss Embassy, which embraces many cultural and social events and activities for residents of different parts of Cairo and Giza. Residents know it well, but not many of them frequent it nor do they relate to it – for them it is not a suitable place for them or they are not suitable for the place.

The Swiss club, a socio-cultural center that hosts middle class weddings in its open garden; it is distinguished by its classy restaurant, and sports and arts activities for children. Most of its patrons are expats in Cairo and people from the middle class, not many of Imbāba’s residents visit the place. (Tadamun, 2015)

On the right hand side of the second half of Ter`et Al-Sawāḥil Street, there is the `Azīz `Izzat housing development, which consists of governmental public housing blocks built on the land which, for many years, had been occupied by the large camel market. The husing development is characterized by relatively wide streets and good lighting with housing blocks of the the same design. Most hosuing blocks are dilapidated and lack basic maintenance of their facilities, yet they remain in a comparatively good condition compared to the surrounding areas. Despite the fact that these government housing blocks are planned and of better physical conditions than many other areas, most of the residents of different areas of Imbāba – even residents of al-Munīra al-Gharbiyya who are stigmatized as poor, violent and criminal – believe that `Azīz `Izzat housing is one of the worst areas in all of Imbāba. There is a belief that drug trade is widespread there with its residents lacking a sense of security. Other features that characterize the area of `Azīz `Izzat housing is the ceramics market, a vegetable market, and a school district, which includes Imbāba Military Secondary School, two secondary schools (for boys and girls), two schools for commerce, and around five schools for primary and preparatory education. There is also another school district in al-Salām street, next to the Swiss Club, and two primary schools in Ter`et al-Sawāḥil street. The Shorbagī factory, the historical factory which was mentioned previously, lies at the end of Ter`et al-Sawāḥil street; there is also an empty plot of land there, which the residents know as “The Porcelain Factory”, because a large porcelain factory had been located there. It was turned into a warehouse after it was closed. The residents tell us that the land is earmarked for constructing new houses and it is also rumored that a large empty plot of land at the end of the factory fence, next to the fire station, will be used for the same purpose.

The poor live in poor homes; they do not have enough money for the maintenance of their homes, they do not have the luxury possessions to decorate them, and cannot afford the cost of a flat so they end up dividing the flats into smaller units, where more than one family live in the same unit. This photograph shows one of the recurring government housing patterns within `Azīz `Izzat housing, where there is poverty, urban and color deterioration (Tadamun, 2015)

The towns of laborers and employees, houses of the middle-class, the best environment in Imbāba and least densely populated.

Behind the railway line and its distinctive bridge along the corniche, lie the residential towns, across the Nile from Būlāq Abu al-`Ilā. Those residential towns, which had been entirely planned by the government in the 1940s and 1950s, housed laborers and employees who passed the flats down to their educated, middle class sons. Their main entrances are from the corniche, and they are considered the best areas in Imbāba, from the point of view of the residents. Their condition has certainly deteriorated due to the mismanagement the area suffered from, like all other areas of Imbāba. However, their streets remain the widest among the streets of all other areas of Imbāba, with a good proportion of greenery, and building heights appropriate to the widths of the streets – albeit higher than planned. The third entrance to Imbāba from the corniche is besides the entrance of Kīt Kāt Square and that of Imbāba police station – this entrance takes you to the heart of the laborer’s residential town by way of Ṭal`at Ḥarb street. At its center is the Foundation Stone Square. It was said that the foundation stone placed by Gamāl `Abd al-Nāṣir to inaugurate the al-Taḥrir Town was at this spot. Ṭal`at Ḥarb street separates the laborer’s town from al-Taḥrir Town. At its center is “El Prince”, the most famous restaurant in Imbāba that specializes in traditional Egyptian meals – it enjoys wide acclaim and receives clients from several areas outside of Imbāba from all over Greater Cairo. The entrances on the corniche side continue with al-Ṭayār Fikrī street then al- Wiḥda street. Those are tree lined main streets, surrounded by a uniform network of side streets and buildings that are in a relatively good condition as well as services, such as Imbāba ambulance unit on Sa`ad Zaghlūl Street in the laborer’s town, and an ophthalmology hospital on al-Ṭayār Fikrī street in al-Taḥrir. Al-Taḥrir town is also distinguished by a school district. Originally it was one primary school called “al-Taḥrir School”, but over time it was sub-divided into eight smaller schools, among them Nile Schools, Refā`a al-Ṭahṭāwī, `Alī Mubārak and others.

The residents of these towns consider that their towns represent civilized Imbāba. They talk with an obvious nostalgia about the good quality of life in those towns in the past, and how those towns represented Imbāba – as they had known it – but that over time it had deteriorated like other areas. They remember that all the surrounding areas were agricultural land. “al-Wiḥda street was constructed, followed by Zakī Maṭar street and al-Gami` street and then the whole area became built-up,” one of the residents of the area told us. He also told us that with the increase in unplanned construction or “slums,” according to him, many of the prosperous people, who were able to save enough money to be able to move to better areas, left.

Laborer’s town and al-Taḥrir town, the planned areas for the middle class in Imbāba. Above: al-Ṭayār Fikrī street, the main street in al-Taḥrir town; above left. Below right: al-Mahdī street in Laborer’s town. Below left: al-Safa street in Laborer’s town (Tadamun, 2015)

The informal building of additional floors in Laborers town, the original building with its stone façade and the higher floors built in brick are apparent. (Tadamun, 2015)

Imbāba’s Nile embankment is characterized by several landmarks and important buildings such as the Government Printing Press and the historic home of the engineer who was responsible for moving the Imbāba Bridge. The corniche strip is also occupied by a number of national institutes, such as the Hearing and Speech Institute, the National Institute for Motor Neuron disease and also the Imbāba Fevers Hospital, which serves several areas outside of Imbāba. The residents consider it the most important hospital in their district and always go there for treatment. They also consider it a landmark preceding another important entrance of Imbāba, namely al-Wiḥda Street, which is a continuation of al-Sāḥil Bridge that starts at Roud al-Farag. The importance of Al-Wiḥda Street lies in the fact that it is the main street leading to al-Būhī Square and al-Būhī Sstreet and from there to El Kawmiyya street which in turn leads to the Ring Road. Its extension – called “Imtidād al-Wiḥda street” – goes into the center of al-Munīra al-Gharbiyya and intersects with al-Oqṣor atreet, one of its most important streets. It is the entry point that leads you to a network of main streets within the depths of all Imbāba.

After al-Sāḥil bridge lie the big grain silos – officially North Giza Flour Mills, and facing it on the Nile bank is a plot of land owned by the Maritime Shipyard, which is now closed. The residents expect that it will be replaced with a park or another recreational outlet on the Nile. Finally, there is the urban legend of the “Chair Factory”. Eventhough the factory stopped manufacturing chairs, was shut down and demolished and al-`Arabī Residential Towers have been built in its place, the site is still known to residents as the Chair Factory. The name extends to encompass the street as well, known as Chair Factory Street, although officially it is called Maḥmūd Sālim street. Although it had been demolished, it is today still one of the most famous factories in Imbāba, and it has become a symbol for mockery that has become wide spread, not only locally but also internationally. The threat “behind the Chair Factory” became the most famous threat for humiliating opponents.

Imbāba grain silos – officially North Giza Flour Mills –on the corniche after al-Sāḥil Bridge – for those coming from the direction of Giza – the entrance is on al-Wiḥda Street in Imbāba. The grain silos own a railway line passing through Imbāba to transport the grains, (Tadamun, 2015)

Imbāba is stigmatized as being unplanned and violent, Imbāba the neglected, crowded, and controversial district; the areas of al-Munīra al Sharqiyya and al-Munīra al-Gharbiyya.

The third area in our tour represents the most controversial Imbāba, the area with the highest population density, and the most crowded; it has the narrowest streets and the poorest services: al-Munīra al-Sharqiyya and al-Munīra al-Gharbiyya. The areas overlap, and it is difficult to define clear boundaries between them. They were all built on agricultural land and expanded at an enormous rate during the last three decades. The divisions of agricultural basins that were essentially the basis of their casual, unauthorized planning are still apparent in the fabric of its physical plan. The houses are crammed together and the streets formed from filling the canals – the large canals became main streets and subsidiary canals between basins became side streets.