Managing public services in the New Cities

Most citizens move to the city thinking that they will have a comfortable life there. They move from one neighborhood to another in an attempt to overcome the challenges of life. Some search for an area close to their jobs or with better work opportunities; others seek out quiet green spaces; and still others move to find better services and utilities. During this hurried attempt, some of the luckiest citizens end up living in what are called “gated communities,” while others cannot afford to live practically anywhere. Providing suitable housing for the less fortunate citizens—and to citizens in general—has always been the State’s most significant task. The Egyptian government, during the last few decades, has worked on expanding and building new cities in an attempt to accommodate the growing population and to shift urban expansion away from densely-populated areas (the valley and delta areas). It has also considered this a strategy to deal with the growth of informal settlements. The impact of the new cities, however, is still insignificant and far from the desired social goals.

Nevertheless, these cities became an essential element of Egyptian urban life. The Egyptian government, in its strategic plans and sustainable development strategy, is still using the establishment of new cities as an approach to solve urban growth and housing issues. It injects large sums of money, taken from public funds, without providing any other alternatives or solutions for development in return. Studying and analyzing all the dimensions of urban planning and management, therefore, becomes essential.

This article explains the organizational structure in which the various governmental authorities work to plan and manage public services in the new cities. It describe ways to design, establish, operate, and maintain new services. We also include an analysis of the impact of these cities’ financial autonomy on planning and management, the effects of their development plans, and finally, whether services meet appropriate standards in the new cities.

The organizational structure of the management of the New Cities

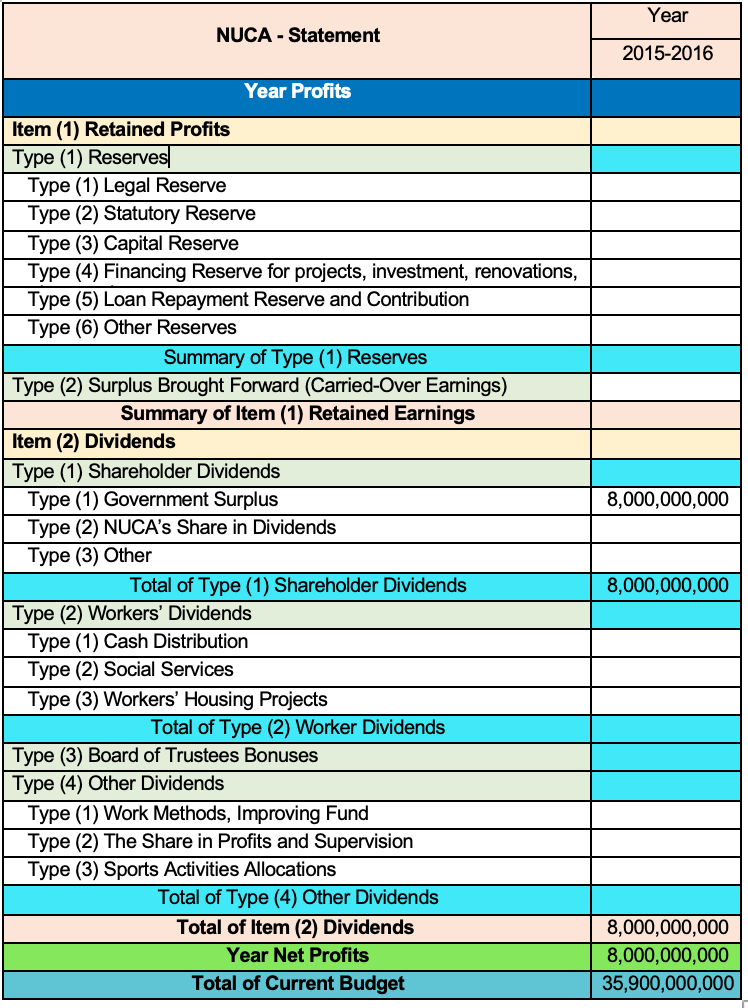

The organizational structure in new urban communities is based on administration approaches and power relationships that are essentially project management. The Ministry of Housing, Utilities, and Urban Communities (MoHUUC) has the mandate to plan and establish new cities, then delegate the management and planning to the New Urban Communities Authority (NUCA). NUCA then sets the New Cities’ Development Agencies (NCDAs) (Law No. 59/1979 Article 44). NCDAs handle executive administration and planning matters, such as establishing public service facilities in the city and then transferring them to the relevant service directorates for management. In addition, NCDAs handle the planning aspects, such as preparing the requirements for the city’s annual development plans. Each city later forms a Board of Trustees (BoT) that collaborates with the NCDA in managing the city. BoTs support the NCDA by coordinating and implementing city cleaning issues (such as contracting cleaning companies and overseeing their work), as well as the gardening, beautification, and maintenance of the city. Moreover, the BoT sets and confirms the coordination plan for the NCDA and the local Non-Government Organizations (NGOs). BoTs also play an advisory role by participating in the crafting of development plans and suggesting clear policies in terms of the pace of the city’s development.

Agencies in charge of the Management of the New Cities

The New City’s Development Agency (NCDA)

Works under the supervision of NUCA. NCDA is responsible for supervising the city’s government services, issuing building permits, and the process of allocating and registering lands.

The New City’s Board of Trustees (BoT)

Responsible for construction permits, determining specialties, sources of income, and areas of expenditures. The MoHUUC usually appoints the members of the BoT from the different stakeholders (investors, homeowner association members, government agencies, public figures, residents). The BoT’s tasks are:

-

Suggesting policies for the development of the new city

-

Studying ways to develop and improve public services

-

Assessing their own efforts in order to decide their level of contribution to the development of the city

-

Coordinating the cleaning and maintenance services

-

Examining the problems of the residents of the city and working on solving them.

The New City’s Investors Association (NCIA)

A local nonprofit organization that aims to:

-

Represent and support the business community

-

Provide business services

-

Develop the city’s community

The association is represented on the BoT, and it contributes to developing the city as well as participating in the city’s development plans through its representatives on the BoT.

The New Urban Communities Authority (NUCA)

NUCA works under the MoHUUC, where it is in charge of all issues related to planning and implementation in the new cities. NUCA establishes executive branches in every new city under the name, “The New City’s Development Agency (NCDA),” and it also identifies the mandates of each agency individually (according to Article 44 of the New Urban Communities Law).

The Ministry of Housing, Utilities, and Urban Communities (MoHUUC)

Responsible for decisions related to financial allocations and expenditures. The minister issues decisions to establish new NCDAs and appoints their heads. NUCA is responsible for the supervision and the planning of the newly-established NCDAs

Directorates of Public Service (DoPSs)

The NCDA establishes public services in the new cities, using a direct contracting approach, and then the agency hands over the newly-established utilities to their respective DoPSs (water, electric, etc.) to operate and maintain that facility. The directors of the various DoPSs represent the government in the new city’s BoTs.

Public services

Public administration experts agree that public services are “the necessary services for sustaining human life and ensuring their well-being,” and that they “should be provided for the great majority of people.” The basis behind providing these services should be the interest of the majority of the community in order to improve the citizens’ standard of living. The State is responsible for providing these services (health, education, culture, security, justice…). It is not a one-time task, but rather a continuous process in which the State plans out the best way to provide them, and continue to develop them, so the citizens receive the best form of those services.

Upon examining the situation in Egypt, we found that the public service planning process differs based on the urban community, depending on the existing authorities in charge of planning as well as the stakeholders influencing the planning process. In the following section, we compare the processes of planning public services (PPS) in the new cities verses the existing administrations.

Planning Public Services (PPS)

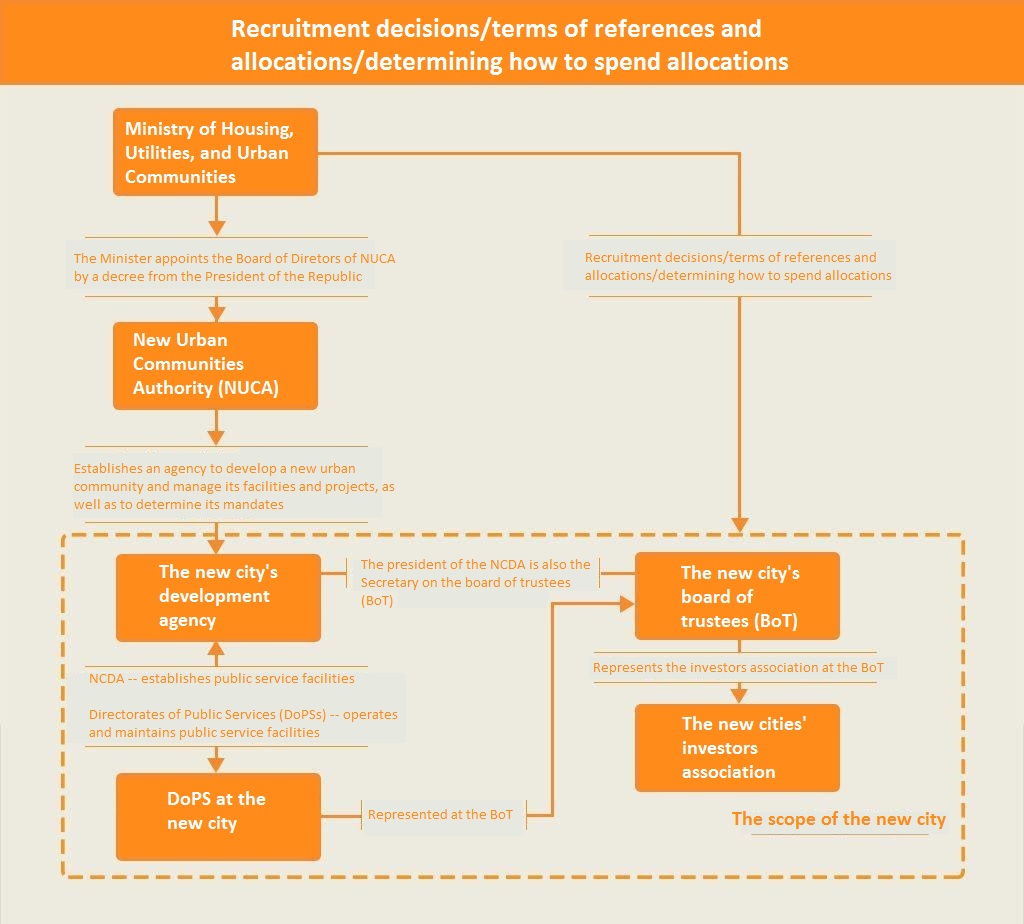

The New Urban Communities Authority (NUCA) is in charge of PPS in new cities while considering the recommendations of NCDAs and their BoTs. The PPS in the new cities goes through several steps:

-

In the beginning, the Master Plan of the relevant city is viewed, then determining the developed-or-provided required public services throughout the year.

-

After that, the available financial resources and the State’s National Planning requirements are identified, as well as the steps to hand the utilities over to the operating entities (whether DoPS or via contracted companies).

-

Finally, an elaborate development plan for the city is then created.

The role of the city’s development agency is to:

-

Survey the city’s needs, in terms of services,

-

Consult with concerned parties in the city (usually the representatives on the city’s BoT) about how to develop and improve the city’s services, and

-

Submits reports on service needs and the stakeholders’ recommendations to NUCA, so that NUCA can use it in preparing a detailed budget for the city.

Planning new cities is also part of the State’s National Planning Requirements (NPR), which primarily concerned expanding social housing projects in the past. Most of the NUCA allocations go to implement housing projects and provide public service facilities for them. An example of this is the development plan for the 6th of October City: LE 24 billion of investments will be injected to serve the social housing expansion project. LE 16 billion was allotted (67 percent of the budget) for building 116,000 housing units and public service facilities in the areas of the social housing. LE 2 billion was allocated (8.3 percent of the budget) to build water and sewage facilities as well as the roads. In addition, LE 2.2 billion (9 percent of the budget) was earmarked to improve the cities’ main roads and intersections.

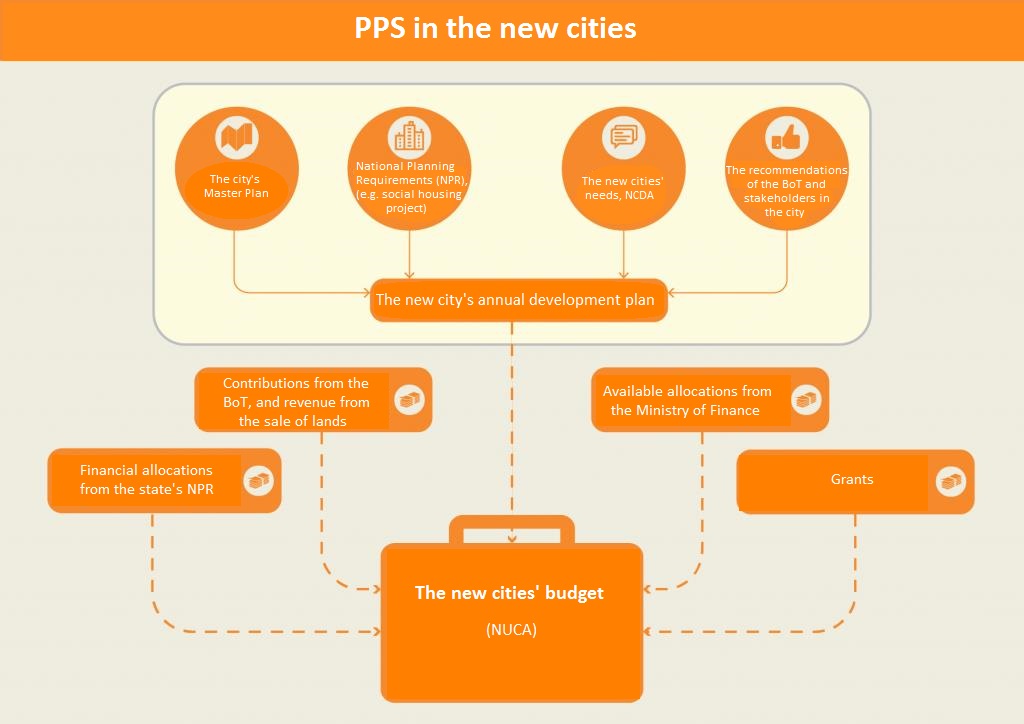

With regard to existing communities (governorates and local unit s, or localities), the PPS process for local units starts with the relevant central, sectoral ministries and the General Organization for Physical Planning. According to Article 65 of the Law of Local Administration (Law No. 43/1979), when creating development plans for local units, each local unit shall identify its needs based on its priorities. Once the local council for approves the budget and the development plan, the budgets then are submitted to the governor then to the High Commission for Regional Planning (HCRP). The Minister of Planning, the Local Administration Minister, as well as ministers of Health, Education and Housing ensure that these development plans match up with the general plan of the State. However, many of the local units’ development and improvement plan items are adjusted to fit the available financial resources or not implemented at all. This happens due to the absence of mechanisms obligating the communication between the estimation of the financial needs in the budget and the estimation of the urban and planning needs. In addition, the Ministry of Finance has the upper hand in determining the financial allocations, not the other ministries.

Who is responsible for establishing, operating, and maintaining public services?

New cities differ from existing cities in some aspects regarding the construction, supervision, and maintenance of public facilities and services. Yet at the same time, they are similar in that representatives of sectoral ministries (DoPS) are in charge of the operation and maintenance of certain facilities (such as education and health) in both new and existing cities. Private sector companies operate and maintain some of the other facilities, such as water services, sewage, natural gas, and electric.

In the new cities, the NCDA generally implements plans and administers the city’s public services. NUCA hands over the overall development plan to NCDA, and the latter builds the public service facilities (buildings and networks) mentioned in that plan. The NCDA then gives the DoPS or private sector companies the responsibility of operating and maintaining these facilities. The new cities’ BoT participates in preparing the development plans and suggests clear and valid policies to expedite the city’s development, based on the priorities of the development projects. NUCA then endorses those plans.

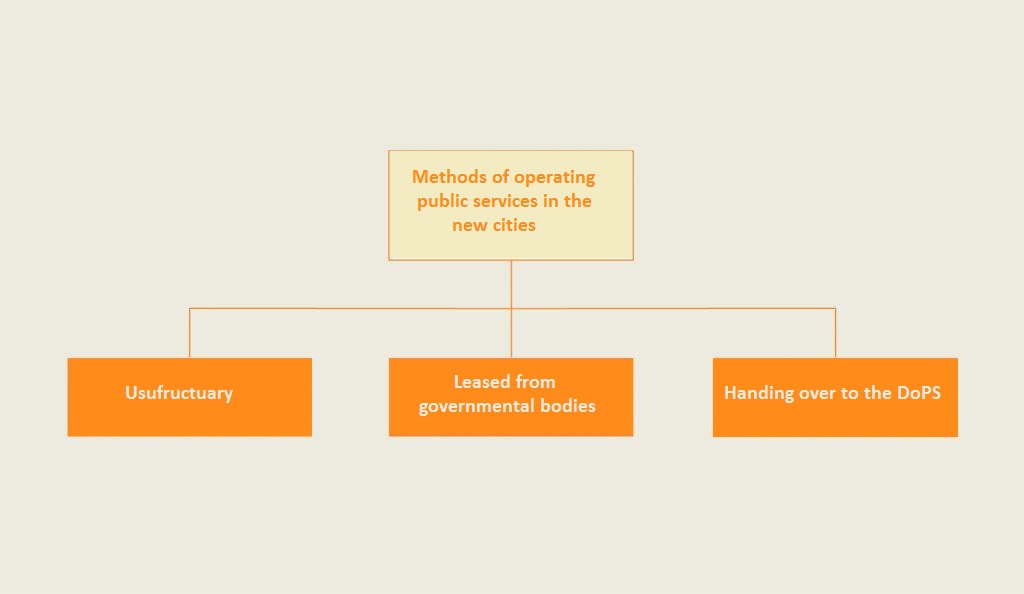

Sometimes, agencies in charge of managing the new city (NCDAs and BoTs) make agreements with the governmental authorities to provide some services via leasing contracts. The governmental entity leases some of its assets to the NCDA, and investors (represented on the BoT) fund this lease. These kinds of agreements are a result of the lack of investment in public services by NUCA, particularly transportation, and the failure to meet the urgent needs of the new city’s community. If the governmental directorates are unable to operate a public service facility, NCDA tries to find alternative ways either through a Request for Proposal or by bringing in local NGOs.

As for existing cities, other than the five local development programs (paving, lighting, beautification, women’s and children’s health, and operational necessities), the sectoral ministries are in charge of establishing, operating, and maintaining public services through the DoPS and offices at the local level. After transferring some public services (e.g., electricity, water, sanitation, and natural gas) to the private sector, construction, supervision, maintenance, and collection became part of the private sector’s job while the DoPS ensures the quality of services. Some claim that handing over operations to the DoPS or private companies has led to the deterioration in public services since this method requires a significant amount of coordination for preparation and implementation. It also requires managerial personnel who are able to act in emergencies. Lack of coordination leads to the waste of available financial resources; as a result, residents do not feel like the service standards have improved. The wealthy, on the other hand, go to the private sector for acceptable health, education, and security services.

Availability and quality of public services in new cities

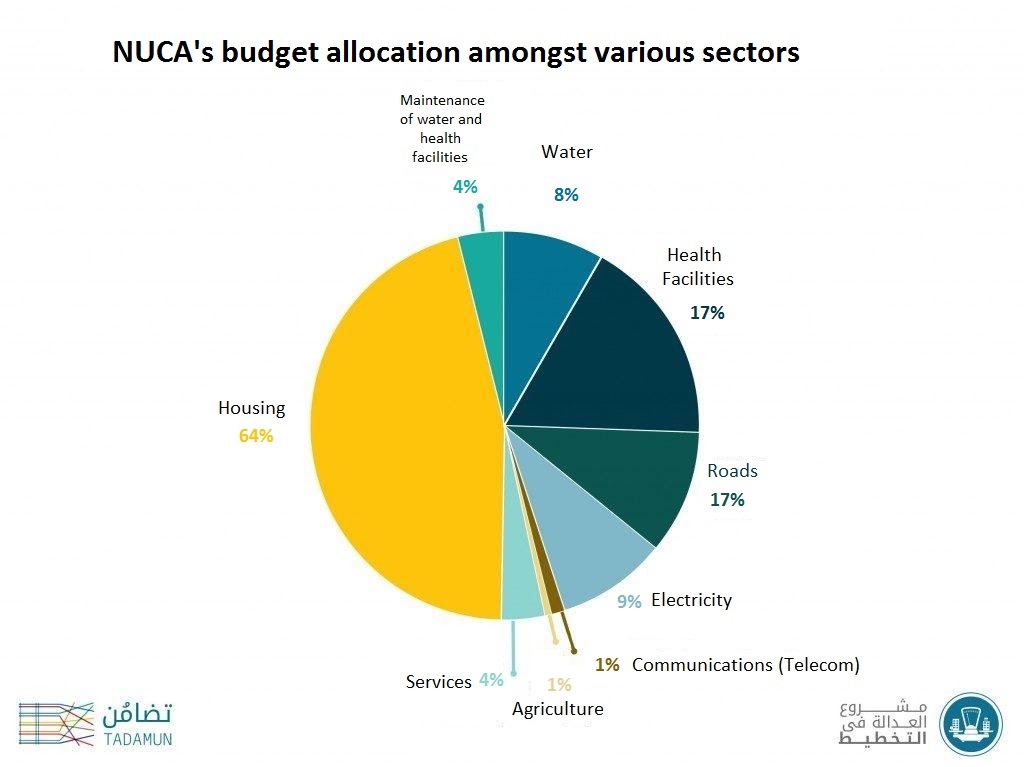

Upon examining the government budget, we found that NUCA receives approximately LE 30 billion in governmental investments (2015-2016 government budget). Less than LE 10 billion of investments went to the sectoral ministries which are responsible for operating and maintaining important public services in new cities (e.g., health and education), which has a significant impact on services provided in the new cities. Taking a more in-depth look at the distribution of NUCA allocations, we find that more than 60 percent of the allocations go to housing (building houses and public facilities). The amount allocated for investments in public service facilities (i.e., water and sanitation) does not exceed 25 percent, and investments maintenance are so low—just 4 percent of NUCA’s budget—that they cover less than 30 percent of facility maintenance needs. Over the long term, this underinvestment will lead to the deterioration of the existing facilities.

One might think that because the cities’ are less than 35 years old, public services would be available, accessible, affordable, higher quality, and better maintained than older cities. As we mentioned in the previous section, the new cities’ Master Plans try to ensure this. However, our research found different realities in most new cities. If we look at health services in new cities, for example, we find that the State is constitutionally obligated to provide decent, close, and reasonably priced health services for all residents. However, the national-level health service is still insufficient and low-quality. NUCA establishes health service facilities in the new cities and then hands them over to the Ministry of Health, upon completion, for supervision and operation. Yet, due to the lack of coordination between the ministries and relevant authorities during the planning phase, the establishment of health service facilities is taking place at a faster pace than the health directorate’s capabilities. Since the local health directorates have fewer financial resources than the NCDA’s, sometimes the health directorates reject plans to take over new health facilities due to the unfeasibility of deploying personnel and equipment in small, less densely-populated areas. Other times, the directorates refuse to accept the units due to technical and structural defects in those units.

Even when the necessary financial resources to operate health service facilities are available, well-trained personnel often refuse to go to the new cities because of the difficulty of the commute, the distance, and the inadequate revenues they generate from working in those areas.

In summary, although NUCA continues to build health service facilities as part of the new cities’ social housing projects, it cannot guarantee the provision of quality health services since health directorates do not always take over these facilities nor operate them due to lack of resources, preferring to focus their scarce resources on areas most in need.

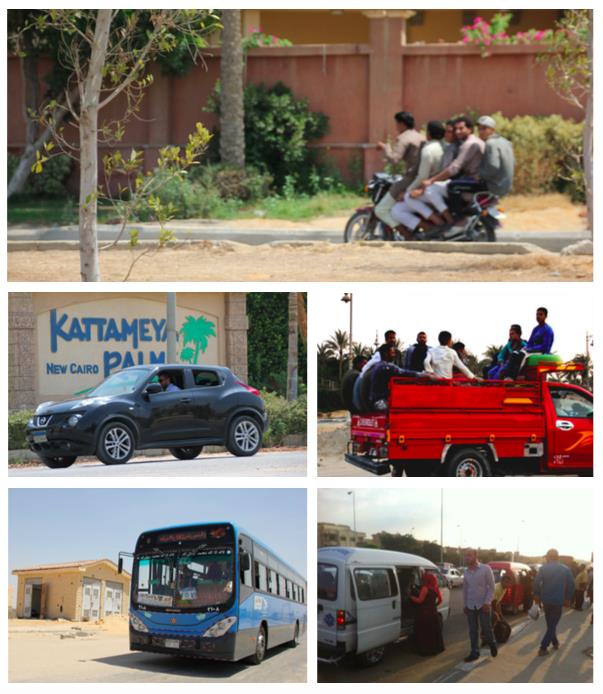

Another example of public services and their suitability in the new cities is public transportation. The lack of adequate public transit most of the new cities shows that planners did not consider linking new cities with the existing ones nor prioritize adding bus routes within them that could help their residents navigate the city. Residents most often rely on the private sector for local transportation (microbuses, taxis, and group transportation projects). After increasing complaints about transportation, some pressure, and “a financial contribution” from the cities’ BoTs, some NCDAs began providing public transportation. It is also noted that recently, in addition to the increase in investment in social housing projects in the new cities, investment in public transit has increased too. We started hearing about agreements with the Public Transport Authority (PTA) to provide lines that link neighborhoods in the new city to the main stops nearby cities. (It is worth mentioning that PTA only operates in the Cairo, Giza, and Alexandria governorates.) Some media outlets also said that there were giant projects, with massive investments, in the works to connect new cities to existing ones. The list includes a monorail project (to connect Sheikh Zayed City and the 6th of October City to Giza); a proposed metro project in the 15th of May City (which would extend the existing metro line beyond Helwan Station to the 15th of May City); and another proposed metro project (linking Heliopolis and New Cairo City). However, we know that these projects are not a part of the official state plans. At the same time, there is no timeline to complete most of these projects.

With regard to the transportation within the cities themselves, NCDAs made agreements with the governorates to allow microbuses to serve those cities along with the buses. They also coordinate with the city’s traffic management to complete the legal procedures. The NCDAs will define the routes and the targeted local areas. In some cases, the PTA contracts some public buses to provide transportation between the outermost neighborhoods and the city center, provided that the BoT bears the cost and NUCA approves the contract.

Financial autonomy and its impact on the cities’ planning and growth

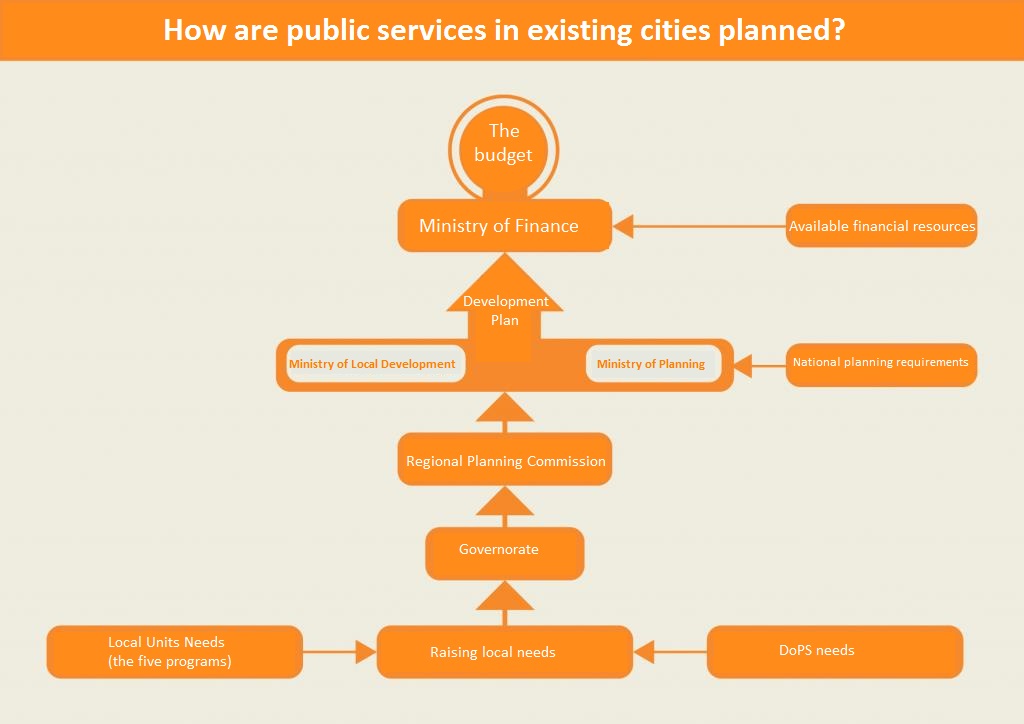

New cities have enough resources to be more independent than local units in existing cities and centers due to the central government’s injection of investment (more than LE 30 billion annually) as well as the contributions of the new cities’ BoTs. The total revenue for the NUCA covers these expenses, and even generates a surplus for the State. Looking at NUCA’s budget for 2015-2016, find that the total budget is LE 35.9 billion, and the expected net profit is LE 8 billion (22 percent of the total budget), making it an outstanding government investment. From comparing government allocations to NUCA with allocations to some of the ministries (e.g. the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Education), we conclude that the government is devoting an increasing interest in the new cities and working on improving and developing them to encourage residents of existing cities to move into the new ones. This means that the government strives to meet NUCA’s needs and to advance and develop the new cities. Recall that the NCDAs determine their needs to improve and develop the city, but it is NUCA that is responsibilt for meeting a significant part of these needs. This, in general, gives the new cities an advantage and increases their capacity for growth and sustainability.

A part of the NUCA’s budget shows the expected net profits in the 2015-2016 fiscal year (Ministry of Finance 2015).

NUCA operates differently from the local administration in existing cities; the latter’s revenue covers less than 10 percent of their expenses, and the government allocations (central government support) make up more than 85 percent of budget for the governorates.

So, in order for local administrations to maximize their revenue, they establish private funds. The income of some local services and fees goes into these funds, and local administrations use the money to improve and develop public services and facilities.

The impact of amending the Master Plan on the new cities’ development planning

In a study entitled “The Decision-Making and Developmental Role of New Cities,” by Dr. Nagwa Ibrahim Mohamed, the active parties in the decision-making process are government groups, businessmen and investors, donors, political groups, residential and community powers, and other groups.

Each group has their own interests and hopes for the city, and each has their own methods to achieve these interests. Some have official leverage that helps them attain their goals, while others benefit from their tangible and intangible powers to pressure other actors to get what they want. Some stakeholders exert pressure to facilitate their affairs in these cities, and they usually are the weakest and least active groups. Although every new city has detailed executive Master Plans from both the MoHUUC the State’s Public Policy framework, upon execution, stakeholders often interfere with the implementation of these plans in various ways to serve their interests, sometimes leading to amendments of Master Plans. For example, Sadat City’s original plan has gone under many amendments in favor of various parties, such as the Prison Department at the Ministry of Interior and Menoufia University. In addition, as a result of the state orientation in recent years to expand the construction of social housing units in new cities, a large part of new cities’ allocations were allotted to implement these projects.

Conclusion

Through our analysis of public services in the new cities and comparisons to existing cities, we have found that the management of public services in new cities is characterized by an exceptional ability to plan and develop public services in the city through existing bodies in the city’s administration, and by the anatomy from the national planning bodies. In addition, the financial resources needed for development and advancement of public services in the city are also available. Some of this funding comes from revenue from land sales as well as contributions from the BoTs and investor associations. We also found that the new cities’ Master Plans drew attention to the planning defects and flaws in existing cities. These cities were planned to accommodate millions of residents from existing cities; however, the new cities have not met their population targets. Finally, we found that the standard of public services was relatively decent, in part due to the age of these new cities compared to existing ones.

As for the challenges public services face in new cities, we found that due to the lack of coordination in the planning phase between planners, those involved in construction, and actors responsible for operating and maintaining new facilities and services, the pace of constructing was much faster than the capabilities of the DoPSs and the private sector. Neither could provide technical and administrative personnel who were able to operate these services. Even when public service facilities have the necessary technical and financial resources, often technically-trained staff refuse to go to the new cities due to the distance, difficulty in commuting, and inadequate income. The expansion of social housing in the new cities presents another challenge, and the fact that most of the budget goes to implementing these projects and providing new public service facilities for them, there are not enough financial resources for the maintenance and operation of existing public services and facilities, leading to the deterioration of public service facilities over the long term. There are competing parties responsible for implementation, and it is often challenging to coordinate and unite their prerogatives, which worsens service delivery and sometimes ends that service altogether. There is a lack of practical oversight tools at the new cities’ level, which have only appointed bodies—there are no elected oversight authorities. These bodies are divided into executive (e.g. NCDA) and consultative bodies (namely the city’s BoT), which possess the power to oversee the performance of the executive agency in the city and hold it accountable.

Finally, due to an increase in the influence of the new cities’ investors associations, we found that some of the NCDA decisions were primarily designed to benefit their own self-interests. These decisions led to amendments to the annual development plans, and sometimes even the Master Plans, creating new financial obligations in the budget.

If we were to summarize the public service administration in the new cities, we would find that despite the anatomy in planning and the excess revenue they generate, both of which should make the development of public services in the new cities easier, public services are not appropriately planned due to a lack of coordination among DoPS and private sector companies responsible for operation and maintenance.

The planning process often does not consider the few resources operational bodies have to implement projects, nor the declining population density in most of the new cities’ neighborhoods. We found that due to the increase of national planning demands in recent years (especially social housing projects), the growth of investors associations’ influence, and a lack of elected oversight authorities, the most significant part of the new cities’ financial resources meet the national demands and benefit the interests of investors in the new cities.

Comments