POLICY ALERT | Budget Transparency and the Citizen Budget of Egypt

Budget transparency is an increasingly promoted norm of government accountability and effectiveness. A budget is a government’s plan to use public resources to meet the needs of its citizens. Budget Transparency (BT) simply means that citizens, voters, and civil society are able to access information about the budget, that is, how public resources are allocated and used by the government. Budget Transparency enables citizens and civil society to assess whether the government is a good manager of public funds and to hold the officials accountable for their actions and budgetary decisions and administrative expertise (Pekkonen and Malena 2012).

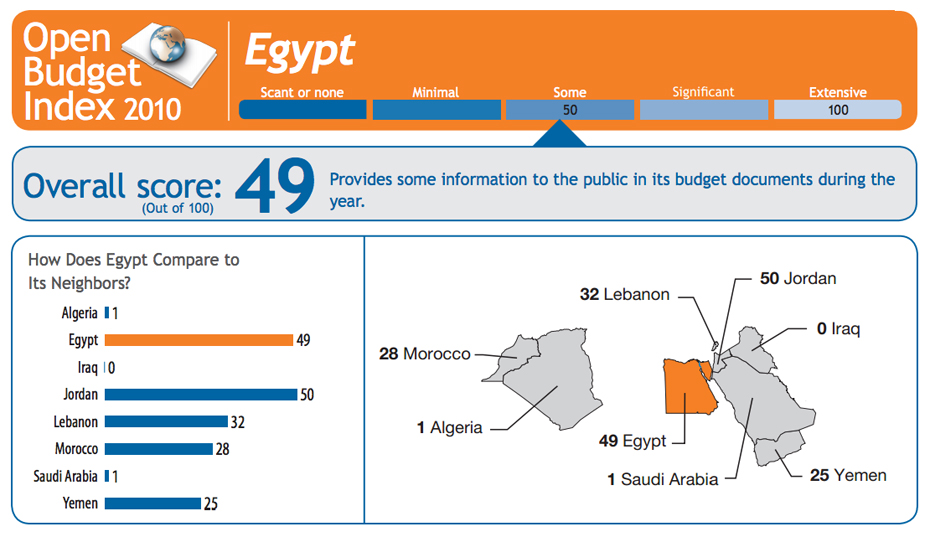

The Open Budget Index (OBI) [1] is a measure of Budget Transparency recently developed by the International Budget Partnership (IBP), a project of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities in Washington, DC. [2]

Placed on this index, most Middle Eastern countries have a much lower score than other developing countries such as Brazil and South Africa because citizens do not have easy access or detailed information about their government’s budgets at the national level (see Figure 1). In 2006, for example, while South Africa and Brazil scored 85.5 and 74, respectively, Jordan had the highest score of budget transparency in the Middle East and North Africa with a score of 50 while many other countries such as Egypt or Morocco had a score of less than 20. The main reason for these low scores is that most of the states in the region do not publicize and share budgetary information openly. Several of the eight key budget documents (a pre-Budget Statement, the Executive’s Budget Proposal, the Enacted Budget, In-Year Reports, a Mid-Year Review, a Year-End Report, an Audit Report, and a Citizen Budget) had never been published in any country in the region prior to 2010.

Source: The International Budget Partnership

From 2006 to 2010, however, Egypt scored the highest improvement in Budget Transparency in the region. One of most significant factors that helped Egypt improve its track record was that it started releasing the Executive’s Budget Proposal (for the President’s activities) and publishing more comprehensive In-Year Reports (providing a snapshot of the budget’s effects during the budget year) and a Year-End Report (comparing the actual budget execution to the Enacted Budget). All these positive steps helped Egypt to score much higher (49) than the average score of Budget Transparency in the Middle East and North Africa (23), which, interestingly, is the lowest average regional score of Budget Transparency.

From 2006 to 2010, however, Egypt scored the highest improvement in Budget Transparency in the region. One of most significant factors that helped Egypt improve its track record was that it started releasing the Executive’s Budget Proposal (for the President’s activities) and publishing more comprehensive In-Year Reports (providing a snapshot of the budget’s effects during the budget year) and a Year-End Report (comparing the actual budget execution to the Enacted Budget). All these positive steps helped Egypt to score much higher (49) than the average score of Budget Transparency in the Middle East and North Africa (23), which, interestingly, is the lowest average regional score of Budget Transparency.

Egypt also attempted to the publication of the its first Egyptian Citizen Budget in 2010; indeed it was the first state in the Middle East and North Africa to do so. According to the 2010 Open Budget Report on Egypt, “a Citizens Budget is a nontechnical presentation of a government’s budget that is intended to enable the public—including those who are not familiar with public finance—to understand a government’s plans.” The Egyptian Citizen Budget suffered from two main deficiencies. First, it was published in December 2010, that is, almost six months after the beginning of the financial year 2010/2011. But more importantly, the language of the content was complex and not appropriate for the average Egyptian with no knowledge of budgetary technical terms. Despite these issues with the Egyptian Citizen Budget, sSoon Lebanon, Afghanistan, and Morocco followed and published their own Citizen Budget reportss.

Source: The International Budget Partnership (IBP). 2010. “Open Budget Index, Case Report: Egypt.”

The revolution of 2011 in Egypt, however, compromised this trajectory. Uncertainty arose from the political instability of the post-revolution era. Since the revolution several key budget documents have not been published. Some of these documents include the Executive’s Budget Proposal, In-Year Reports, and the Citizen Budget. Moreover the legislature and other audit institutions played no role in the formation or oversight of the budget, as the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) approved the state budget of 2012/13 fiscal year without consulting any other institution. [3] All these factors decreased Egypt’s budget transparency score to a new low of 13 in 2012.

Why Does It Matter?

Dr. Youssef Boutros Ghali, the Egyptian Finance Minister, when announcing the first Citizen Budget initiative in 2010 said that the Citizen Budget is one of the mechanisms to reinforce financial decentralization because it allows the citizens to know how public revenues are raised or created by the government and where they are spent. [4]

Transparency helps citizens to hold their government accountable for their spending priorities and the allocation of public funds. The Citizen Budget shares government information with citizens in a way that is digestible for the vast majority of the people. By making information public, a Citizen Budget decreases the chance of corruption. Corruption is more likely to take place where no one knows where, how, or why public resources are utilized. Publicly-issued budgets decrease the chance of government malfeasance by giving politicians, citizens, and civil society more information and resources to judge government performance and to track public revenues.

Budget Transparency empowers civil society to be more engaged in economic governance by enabling it to participate in the process of decision making for national, regional, and local budgets (Dubosse and Masud 2011). Budgetary knowledge improves efficiency; it improves the implementation and monitoring of projects as well. For example, in the case of Mit ‘Uqba, a densely-populated area in Cairo, local residents learned about the costs of paving their streets after negotiating with the local administrative unit. The persistent demands of the Mit ‘Uqba Popular Committee for the Defense of the Revolution encouraged the government to share budgetary information, maps, and project plans for the district and governorate and with this information, the residents also began overseeing the project and monitoring the quality of the workmanship, the cost of labor, and cost effectiveness of project materials in both the long and short term. They knew the project’s budget and the guarantees and terms made by the contractor. They could match this information with the quality and timing of the work done by the contractor and ensure that there was no corruption. The project proved that access to budgetary information increases the efficacy of community-driven initiatives and enhances the ability of local residents to supervise projects closely.

Challenges Ahead

Budget Transparency is by no means a guarantee for citizen engagement and government accountability. Publication of Citizen Budgets may not mean that the content serves the greater public’s needs. In its most non-democratic form, Citizen Budgets can be used by authoritarian regimes to support their own legitimacy. In order to be eligible for foreign loans from international donors, for example, many authoritarian regimes are often required to take certain steps toward transparency and more social, political, or economic openness. Publishing Citizen Budgets and other budget documents not only makes these regimes appear more transparent based on indices such as the OBI, but also helps the regime to claim that it engages the society in one of the most critical public issues. This might have been the logic of Egypt’s decision in 2010 to issue its first Citizen Budget and the Executive’s Budget Proposal. Despite publishing these documents, the Egyptian government never engaged civil society in the process of formulating and overseeing the budget. The regime did not even listen to elected representatives in the Majlis al-Sha’b. Despite the fact that ninety-eight Parliamentarians wrote a memo to reject the 2010 budget report, the report was approved in the People’s Assembly. [5] As the Egyptian case demonstrated, printing a budget does not mean allowing real input from citizens to prioritize government spending; it may only mean that the government prints its financial priorities without any real democratic deliberation at the national, regional, or local level and more importantly, accountability that revenues were actually spent according to the budget rather than the shifting whims of the ruler or those in power, behind closed doors. While Budget Transparency may increase the likelihood of accountability it does not create accountability.

As the Mit ‘Uqba project indicates, Budget Transparency can also be effective at the local level. Most of the states with high levels of Budget Transparency such as Brazil (see Figure 1) are in fact countries where local government has autonomy from the central government to raise revenue and allocate public funds, develop their budget goals, and implement policies that meet those goals. Accountability becomes an easier challenge to meet when it is practiced at a small scale. While citizens can hold a local official accountable, it is much more difficult for them to hold the central government accountable for the sums allocated to different sectors at a large scale. This, however, is true about countries with a minimum level of democracy where at least the officials are elected by the people and, as such, accountable to the people. Egypt, however, lacks strong local government and independent budgets (see “Who Pays for Local Administration” for more information on the financial dimension of local government in Egypt), which makes accountability a more difficult challenge to meet.

Moreover, the uncertainties of the Egyptian political transition, which has already undermined the Egyptian Budget Transparency score, may prod civil society to demand more transparency again. Civil society hopes for a more democratic state which can enable them to supervise the efficient, fair, and appropriate use of public funds.

Access to information in general is an essential right for citizens in democratic countries. Egypt does not have any law that guarantees the right to information. The government should take measures to improve the accessibility of budgetary information in order to improve government transparency and accountability. Without citizen engagement in Egpyt, deepening democracy will be an arduous task.

Work Cited:

Arab Republic of Egypt, Ministry of Finance. 2011. Muwaazina al-Muwaatin. Retrieved from http://www.mof.gov.eg/MOFGallerySource/Arabic/Balancing-citizen10-11/Balancing_citizen.pdf. (in Arabic).

Dubosse, N. and Masud, H. 2011. “Open Budgets, Sustainable Democracies: A Spotlight on the Middle East and North Africa.” The International Budget Partnership (IBP). Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://internationalbudget.org/wp-content/uploads/Open-Budgets-Sustainable-Democracies-A-Spotlight-on-the-Middle-East-and-North-Africa.pdf

“Egypt’s military council approves 2012/13 state budget.” 2012. Ahram Online. 2 July. http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/3/12/46676/Business/Economy/Egypts-military-council-approves–state-budget.aspx (Last Accessed: June 17, 2013)

“NDP and Brotherhood fight over general budget.” 2010. Egypt Independent. 31 March. Retrieved from http://www.egyptindependent.com/news/ndp-and-brotherhood-fight-over-general-budget (Last Accessed: June 13, 2013)

“OECD Best Practices for Budget Transparency.” 2002. OECD Journal of Budget. Retrived from http://www.oecd.org/governance/budgeting/Best%20Practices%20Budget%20Transparency%20-%20complete%20with%20cover%20page.pdf

Pekkonen, A. and Malena, C. 2012. “Budget Transparency.” CIVICUS. Retrieved from http://www.pgexchange.org/images/toolkits/PGX_G_Budget%20Transparency.pdf

The International Budget Partnership (IBP). 2010. “Open Budget Index, Case Report: Egypt.” Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://internationalbudget.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/OBI2010-Egypt.pdf

The International Budget Partnership (IBP). 2012. Open Budget Index (dataset). Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://internationalbudget.org/what-we-do/open-budget-survey/country-info/

The International Budget Partnership (IBP). 2012. “Open Budget Survey Biennial Report.” Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://internationalbudget.org/wp-content/uploads/OBI2012-Report-English.pdf

United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP). 2013. “What is Good Governance.” Retrieved from http://www.unescap.org/pdd/prs/ProjectActivities/Ongoing/gg/governance.asp (Last Accessed: June 12, 2013)

[1] OBI is the first comparative index for budget transparency at the national level. While it makes comparison easier, this index suffers from certain problems such as ignoring the particularity of the context, as well as neglecting local and regional levels of analysis.

[2] The Open Budget Index (OBI) is based on the biennial Open Budget Survey and is calculated as a simple average score of responses to 95 questions in the Open Budget Survey. The Survey is completed by independent researchers from the academia and civil society in the countries assessed. The OBI ranges from 0 to 100 with greater scores resembling higher levels of public availability and comprehensiveness of budgetary documents (Open Budget Survey 2012; see also the 2011 Arabic questionnaire).

[3] Ahram Online. (2 July 2012). Retrieved from http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/3/12/46676/Business/Economy/Egypts-military-council-approves–state-budget.aspx

[5] Egypt Independent. (31 March 2010). Retrieved from http://www.egyptindependent.com/news/ndp-and-brotherhood-fight-over-general-budget

Comments