Social Function of the City and of Urban Property in the Egyptian Constitution

Is the average citizen the main beneficiary of government projects? As a property owner, can I do with my property as I please or are there guidelines that protect the public good? Do individual rights supersede the collective? The social function of the city and urban property is at the heart of urban rights, as it regulates administration and land use to move towards a more socially just and inclusive city, protecting the collective rights of inhabitants to a decent life.

What is the Social Function of the City and Urban Property?

The social function of the city embraces the idea of social justice and the notion that the city belongs to everyone. It recognizes that every person should be able to enjoy the full range of resources offered by the city. Public resources should be used to guarantee the well-being of all inhabitants by providing public and private spaces and urban development projects that prioritize social, cultural, and environmental interests of the community. All inhabitants should enjoy green spaces, schools, parks, and safe public spaces. Public resources and citizens’ taxes should not only be invested in a few upscale neighborhoods. If one person enjoys all the benefits of being a citizen of the city, while her neighbor does not, the social function of the city has not been realized. The constitution should compel the city and its legal, administrative, and financial institutions to promote and protect the collective interests of all inhabitants.

Closely related to the social function of the city, is the social function of urban property. The social function of property recognizes the impact of property ownership and use on the larger community. It is the idea that “my” property is a part of “our” city, and it prioritizes “our” city over “my” property. It recognizes that property owners have obligations to serve the community through a productive use of their wealth. The government should be obligated to implement policies that allow for public and private properties which are deserted, unused, underused, or unoccupied to be put to full, productive use. The burdens and benefits generated by the urbanization process and public investment should also be distributed justly.

Effects on Our Everyday Life

Are State Investments Directed Towards the Majority or the Elite?

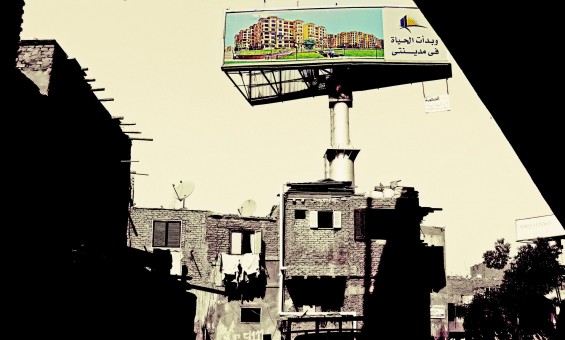

Over the past few decades, the government has been selling desert land surrounding Cairo to individuals and private companies for development. Private developers slow down or halt construction on these desert properties – purchased cheaply from the government – and wait for the value of their private holdings to increase through public investment in infrastructure, yet that same public investment could have been directed towards existing cities where the vast majority of the population lives. Through this process of urbanization, the worthless piece of desert land gains considerable value, all of which accrues to the property owner through no action of his own. Not to mention that this increase in land prices in new cities is reflected in skyrocketing housing unit prices that is unaffordable to millions of Egyptians.

Unused Private and Public Properties

There is an acute shortage of affordable housing in Egyptian cities. However, despite this shortage, as of 2006, 25% of housing units were vacant in Cairo governorate, 32% in Giza and 35% in Alexandria governorates1.

It is also expected that this percentage has highly aggravated since 25 January 2011 due to ramping and uncontrolled building activates spreading in all Egyptian cities.

Why are these homes empty? Here is the social function of property at work. Outdated policies keep apartments shuttered and out of the reach of those who need them the most. This is not to say that the units should be taken over by the state or declared open to squatters, but the Egyptian government should enact effective property tax laws that govern property use and efficiently utilize vacant and speculative properties, as well as policies that ensure a fair rental market for both tenants and landlords. Public investment in public transportation links and other services are also needed to make these new cities equally accessible to all.

Unused properties are also a problem that reaches public property as well, with many unused publicly owned lands in densely-populated areas that serve no public benefit except for being a eyesore for residents who are in need for space for public services or facilities. This is the case in Ezbet Khayralla, where 650,000 residents are deprived of all public services – except for one public school – and there is no space available to offer them, except for a large fenced vacant land (about 37 acres) owned by the governorate. For years, and until today, this precious vacant land has been occupied by the Ministry of Interior which was using it for a while as a “Horsemanship and Polo” club in this poor neighborhood.

Equitable Distribution of Services and Burdens

The benefits of urbanization accrue disproportionately to a small segment of Egyptian society, while the burdens are disproportionately borne by poor people and marginalized groups in Egypt. One need only stroll through Manshiyyit Nasser to see that Cairo’s growth has not been kind to the poor. In other areas, historic neighborhoods are renovated to attract tourism rather than to benefit their long-standing residents who might even get evicted because of these renovation plans. In addition, urban planning schemes prepared and adopted by the state in the recent years demonstrate an appalling bias towards the rich, on the expense of the poor neighborhoods which are treated – along with their inhabitants – by these urban planning schemes as if they do not exist in the first place. As a result, we never see such ambitious road widening proposals, redevelopment plans, and even demolition of entire neighborhoods and evicting their inhabitants in favor of investors except in the poor and under-privileged neighborhoods of our Egyptian cities. And despite the efforts of the Egyptian state to extend utilities and public services in many under-privileged neighborhoods, we still have a long way to go to ensure the equitable distribution of these utilities and services among different neighborhoods.

The Fine Line Between Individual Rights in Private Property and Public Interest

If I own a property of historical or architectural value, do I have the right to demolish it or change it significantly? If you own a piece of land, do you have the right to develop and construct it in such a way that may endanger neighboring properties, invades inhabitants’ privacy or obstructs their access to natural light and proper ventilation? Do you have the right to leave your land or property unused till it becomes another abandoned building or landfill that harms neighboring residents? And do government agencies have the right to refuse developing its vast areas of land near densely populated areas for the benefit of these residents and instead sell it to investors for a huge profit?

In the newspapers it is not uncommon to read about yet another demolished historic building and replaced by a high-rise building or a foreign investor who purchased a landmark hotel in a key location overseeing the Nile, only to leave it unused for years.

And of course there are residential buildings collapsing in popular areas (this happened several times in Alexandria over the past few months for example), with fatalities and damages reaching surrounding buildings as a result of contractors’ and property owners’ greed and disregard of building regulations and height restrictions. Not to mention high-rise buildings and shopping malls overshadowing popular and historic areas and lowering the quality of life of residents by obstructing natural light and ventilation, overloading the already deteriorated infrastructure, and invading the privacy of their everyday life.

All of the above are symptoms of the conflict between individual rights of property ownership (which needless to say should be protected and respected) and the individual’s right to “develop” that property. And this is where the social function of urban property comes in to organize the relationship between property ownership and development rights. Ownership rights are protected, but the social function of property enforces obligations on owners in the development of that property and prevents it from being left unused. These obligations are based on the pivotal role these properties should play in the service of society and the realization of public good, or at the very least prevent its harm.

The Constitutional Right to the Social Function of the City and of Urban Property in the Egypt

There may not be clear laws or institutional mechanisms to implement it, but the social function of property is mentioned explicitly in the Egyptian Constitution in the first constitution drafted in 1954 after the fall of the monarchy. Article 32 in the 1954 constitution acknowledges the social function of property and that it shall be organized by law, and that property confiscated in the public interest should be compensated for fairly and in advance. The 1971 Constitution Article 32 affirmed the role of the social function of property in serving the national economy within the framework of the national development plan. The same article added that “the ways of its (property) utilization should not contradict the general welfare of the people,” which was removed in the 2012 and the 2014 constitutions.

The 2012 and the 2014 constitutions articles related to the social function of property are almost identical to each other. Article 35 in the 2014 constitution states:

Private property is protected. The right to inherit property is guaranteed. Private property may not be sequestrated except in cases specified by law, and by a court order. Ownership of property may not be confiscated except for the public good and with just compensation that is paid in advance as per the law.

Even though the social function of property has been in the Egyptian Constitution for the past sixty years, national policy and state practices have consistently acted against this principle. This shows that simply having the phrase “social function of property” in the constitution is not enough to guarantee this principle, unless mechanisms are outlined to ensure its implementation and specific agencies are responsible for carrying it out.

Global Examples

Many countries in Latin America and Europe have included elements of the social function of the city and of urban property in their legal system. The Brazilian constitution (1988) is one of the most comprehensive and insightful constitutions in this regard.

Article 170 of the Brazilian constitution (1988) makes the social function of property one of the general principles of the national economy and articulates that the national economic order should be “intended to ensure everyone a life with dignity, in accordance with the dictates of social justice.”

Also, Article 5 states that “property shall observe its social function” and that “the law shall establish the procedure for expropriation for public necessity or use, or for social interest, with fair and previous pecuniary compensation.” And, Article 156 allows the municipalities to collect taxes on urban buildings and urban properties, “in order to ensure achievement of the social function of the property.”

Article 182 states that urban development plans should fulfill the social function of the city:

The urban development policy carried out by the municipal government, according to general guidelines set forth in the law, is aimed at ordaining the full development of the social functions of the city and ensuring the well-being of its inhabitants.

To dissuade owners from property speculation, Article 182 also grants municipal governments the right – by means of a specified law – to subject the owner of “unbuilt, underused, or unused urban soil provided for adequate use” to compulsory construction and urban property and land tax rates that are progressive in time, as well as similar deterring actions.

In 2001, Brazil passed the City Statue and legislation to enforce Article 182 of the Constitution and the social function of property by prioritizing social interests over individual ownership rights to end property speculation. Of course, many would argue that the social function of property has not been fully realized in Brazil, but these constitutional principles provide voters, legislators, and citizens a legal basis to fight for these rights to be implemented and enforced.

The Columbian Constitution (1991) clearly states in Article 58 that in the case “conflict should occur about the rights of individuals, the private interest will yield to the public or social interest.” The article also states “property is a social function that implies obligations. As such, an ecological function is inherent to it.”

The Brazilian Constitution also extends the concept of social function of property to agrarian land, as outlined in Article 185 and 186, which refer to the rational and adequate use of land, natural resources, preservation of the environment, as well as compliance to labor relation regulations. Similarly, Articles 31, 66 and 282 in the Ecuadorian Constitution (2008) expand the understanding of the social function to include the environmental function of property.

These articles collectively organize the role of social and environmental function of property in achieving comprehensive “urban rights” for all, protecting collective societal rights in private property, and introducing mechanisms for land allocation between citizens that respects the social and environmental function of property

The Way Forward

As the World Charter for the Rights to the City articulates, the collective social and cultural interest should be prioritized over individual property rights. This, however, does not mean that individual rights should be overlooked. The Egyptian constitution already mentions the social function of property but more elaboration is needed to ensure its implementation. For a more comprehensive adoption of this principle, the following aspects need to be put in mind:

Urban areas should perform their social function so that all inhabitants can benefit from available resources. The government should direct public projects and investment towards the public good.

Urban public policies should promote social benefit and collective culture over individual property rights and real estate speculation. In order to realize the social function of urban property, legislation should guarantee the optimal usage of under-utilized, unused, or vacant public and private property.

The state should regulate real estate speculation by developing suitable policies to fairly distribute the burdens and benefits of urbanization and by adopting economic, taxation, financial, and budgeting tools that seek to realize fair and sustainable urban development.

Financial returns resulting from public investment or urban redevelopment should be earmarked for the renovation of the same area in a way that will benefit its original residents, with all excess returns allocated to funding social programs that guarantee the right to adequate housing and provide a dignified life to the population groups living in substandard and unsafe conditions.

1. Calculated from 2006 CAPMAS data↩

Featured Image: “Life begins in Madinaty” Which city they’re talking about!? Photo by Moustafa El Shandwely, shared on Shandwely photography facebook page, used with permission.

Comments