What Can We Learn from the `Izbit Al-Nakhl Evictions?

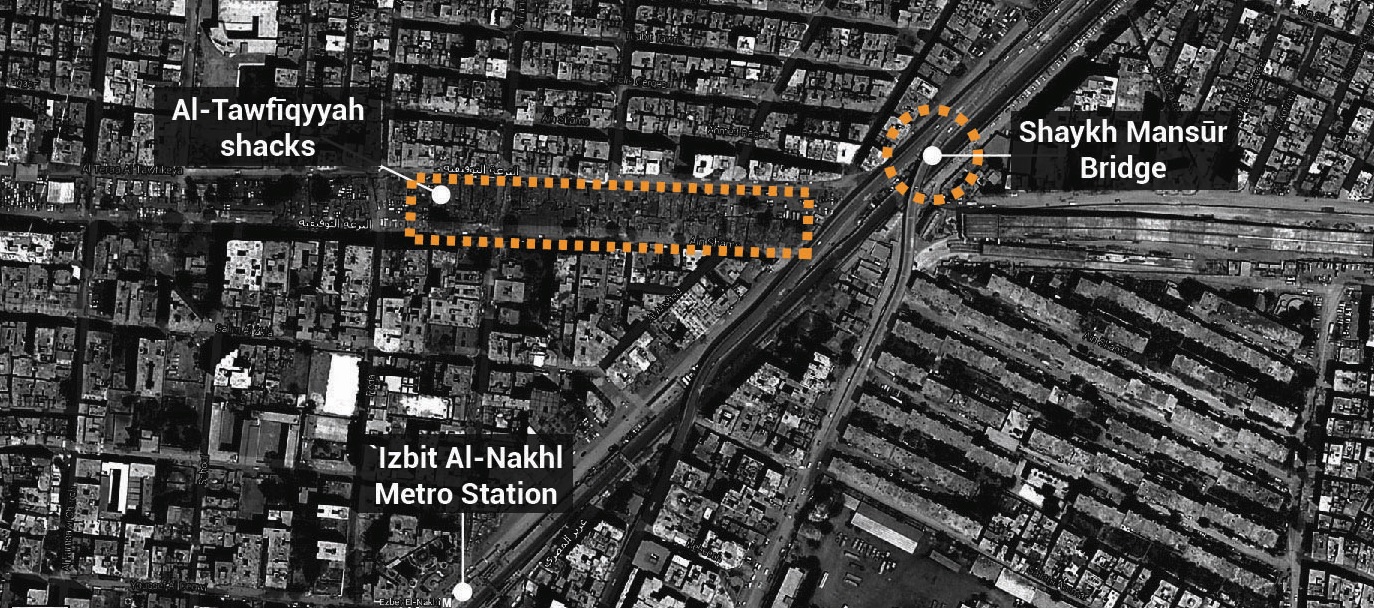

On March 3rd 2014 a press conference was held by a number of political parties and Egyptian Civil Society Organizations in response to the eviction of a number of residents in `Izbit Al-Nakhl. The eviction took place in the wake of the collapse of a bridge, making the situation life-threatening for the approximately 11 shacks beneath it. In addition to removing the shacks beneath the bridge, Al-Tawfīqyyah shacks – a nearby larger community – were also removed in order to make way for a new bridge that would tie the Ring Road to Eastern Cairo.

The Story: Controversy and Contradictory Information

On February 11th a bridge partially collapsed in North-Eastern Cairo after a fire broke out among the shacks below it. The collapse of the Shaykh Mansūr Bridge, which connects the Al-Marg and `Izbit Al-Nakhl districts, prompted the eviction of the people living below and around the bridge. Most eviction processes are usually fraught with controversy, and this one was no exception as it was condemned by local human rights organizations. The controversy is related to three main issues:

The first issue is in regards to the process of eviction, which relied on the notorious Central Security Forces (CSF) and involved heavy use of teargas. According to residents, security forces attacked in the early morning while residents were sleeping, destroyed their possessions, and used excessive violence that led to injuries, arrests, beatings (including women), and children having to be rushed to the hospital to be treated for teargas suffocation. Officials stated to the media that security forces initially called on residents to evacuate their tents and head to the Governorate to document their right to compensation, and that the residents refused to leave, forcing them to resort to teargas.

The second issue is regarding the form of compensation, as residents claim that instead of being given homes, they were given temporary shelters that they would be allowed to use for only 15 days, after which they would be kicked out and left to their own devices, the exact situation which forced them to live in shacks in the first place. Many have already received eviction notices stating that their 15 days are up and they must leave the premises.

The third issue is related to the number of people eligible to receive compensation, as the census used by the Governorate was almost two years old, and residents claim that many were not compensated because they were not included in the 2012 inventory. The Governor of Cairo claims that all the original residents of the area were provided with alternative homes, and that when it became known that a bridge will be built in this area, families started coming in from different parts of the country and squatting there in the hopes of receiving free accommodation1.

Overall, the 11 shacks that were beneath the collapsed Shaykh Mansūr Bridge have been allocated alternative – albeit temporary – homes. Accurate information regarding the nearby Al-Tawfīqyyah shacks is more difficult to come by. The Governor of Cairo stated to the media that 432 families from among these shacks have received alternative homes, while the families’ lawyer stated that around 420 families received homes, while over 80 families have not.

Lessons for the future

Currently, the de facto situation in Egypt is that legal tenure is directly linked to government recognition of one’s rights as a citizen. If you do not have tenure papers, you are effectively stripped of your rights, which goes against not only the Egyptian Constitution but also the international covenants ratified by Egypt.

In 2012, Egypt, along with a number of other states, adopted a set of guidelines on urban tenure which states: “When it is not possible to provide legal recognition of tenure rights, States should prevent forced evictions that are inconsistent with their existing obligations under national and international law”. In regards to national legislation, Article 63 of the Egyptian Constitution explicitly forbids “arbitrary forced displacements” and Article 78 guarantees the right to adequate housing. As for international law, Egypt is party to the ICESCR which also guarantees the right to adequate housing in Article 11.1.

In addition, General Comment 4 issued in 1991 by the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights explicitly recognizes ‘Security of Tenure’ as the first fundamental element of the right to adequate housing as it states: “Notwithstanding the type of tenure, all persons should possess a degree of security of tenure which guarantees legal protection against forced eviction, harassment and other threats. States parties should consequently take immediate measures aimed at conferring legal security of tenure upon those persons and households currently lacking such protection, in genuine consultation with affected persons and groups.”

Aside from Egypt’s legal obligations to guarantee adequate housing and safeguard human rights, there are a number of existing internationally-recognized standards on how to carry out eviction processes. Such standards can give us insight into what the Egyptian government should do differently, particularly Comment 7 on Article 11.1 of the ICESCR, and the 2007 UN report on the guidelines for development-based eviction. According to these standards, certain conditions should be observed before, during and after carrying out such mass evictions. These conditions include prior notice to the residents, informing the residents why they are being evicted and where they will be relocated to, carrying out the eviction at a reasonable time of day, restricting violence, not harming any of the residents’ possessions, accessibility to neutral civil society observers, and providing immediate alternative adequate housing.

While it is important to acknowledge that some development projects or situations of eminent danger may necessitate the removal of some residents, particularly when on state-owned land2, it is equally important to preserve the rights of those being evicted. Eviction processes should not be left to the discretion of executive agencies, but should rather be governed by standards designed to ensure the protection of the rights of all parties.

However, when it comes to reality, most of the above measures are violated in almost all the eviction cases in the Egyptian context. This can be partially attributed to a wide-spread lack of understanding among Egyptians that security of tenure – even with the lack of legal recognition – is a given right recognized by the UN and many countries including Egypt.

The 2014 Egyptian Constitution recognizes the right to adequate housing, and implicitly the right to security of tenure. The Constitution also holds the State accountable for the fulfillment of these rights. However the State’s behavior in Izbet El-Nakhl came in flagrant contradiction with a constitution it highly promoted and praised. This paradox partially stems from lack of clear definitions of different rights in the 2014 Egyptian Constitution based on agreed upon standards, if not lack of willingness of the State to abide by the principles of this new constitution. Some activists and urban rights groups tried to overcome such lack of articulation and definitions through developing a comprehensive constitutional approach towards Egypt’s urban problems, including the right to security of housing tenure.

But more importantly, if there is one lesson we can learn from what happened in `Izbit Al-Nakhl it is that even with the best constitution ever, it will remain ink on paper until people know their rights, demand them and make sure they are fulfilled on the ground.

1. One resident claims that he, along with a group of residents, tried to present an updated census to the District Head but was forcibly prevented from entering the District building, and were later surrounded by the police and forced to leave. This is an ongoing problem, as of March 12th the Egyptian Centre for Civil and Legal Reform (ECCLR) issued a statement that 150 families that had had their shacks demolished were not provided alternative accommodation and had been sleeping on the street since mid-February. In response they stormed a number of nearby vacant housing units as a way to pressure the government. On the other hand, other residents claim that some of those who received compensation are not actually from among the shack-dwellers at all and actually arrived from other areas of Cairo in the hopes of getting a home.

2. Keeping in mind that some of the `Izbit Al-Nakhl residents who were denied compensation have presented documents that show they have been paying property taxes as well as an official document from the General Prosecutor legally preventing their eviction.

Feature Photo via @LoveLiberty on twitter.

Comments