Cairo 2050 Revisited: Cairo’s Mysterious Planning – What We Know and What We Do Not Know About Al-Fusṭāṭ

There are many things that can be said about planning in Egypt. Transparent is not one of them. As discussed previously in another TADAMUN article on urban issues –“Where is Cairo’s Strategic Development,”– figuring out how urban plans are being designed and implemented in any given area of Egypt’s capital, Cairo, usually involves searching for random pieces of information from various sources that almost always leads to a muddled and self-contradictory picture. To illustrate this further, this article will provide a prime example of the mystery and ambiguity that almost always surrounds Egypt’s urban planning.

Background

Al-Fusṭāṭ was established as the first capital of Egypt under Muslim rule, situated today within the Masr Al-Qadima district which literally means “old Egypt.” While initially it was the center of power in Egypt, today it is dealing with urban decay as most of the city’s resources continue to be siphoned away from the historic core towards the newer areas. It lies towards mid-South-Western Cairo, just North of Maadi district. Al-Fusṭāṭ hosts many tourist attractions such as the 7th century Amr Ibn Al-‘As mosque (the first mosque in Africa) as well as the Hanging Church and the Ben Ezra synagogue. However, as the area predates modern planning in Cairo, it is predominantly unplanned and in poor condition due to decades-long neglect by the state. As such, Al-Fusṭāṭ area has been the subject of planning efforts by the state to develop its vast archaeological sites and declining neighborhoods; and capitalize on its tourist attractions and historic landmarks.

What We Know

Public information about plans for Al-Fusṭāṭ is not easy to find. One can obtain relevant information from either: 1) official plans and documents presenting proposals for the area; or 2) statements by officials to the media that reveal what is supposedly taking place in the area.

In regards to official plans, Al-Fusṭāṭ was part of a study conducted by the Ministry of Culture in 2006-2007 on the potential for land-use re-planning called “Reconsidering Al-Fustat.” This study was related to the construction of the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization (NMEC), also known as the Al-Fusṭāṭ Open Museum, in Al-Fusṭāṭ. The museum would be only the first step in turning the area into a “touristic historical node inside Cairo” which, according to the document, would entail the construction of a historical theme park, cinema complex, archeological park, hotels and a garden.

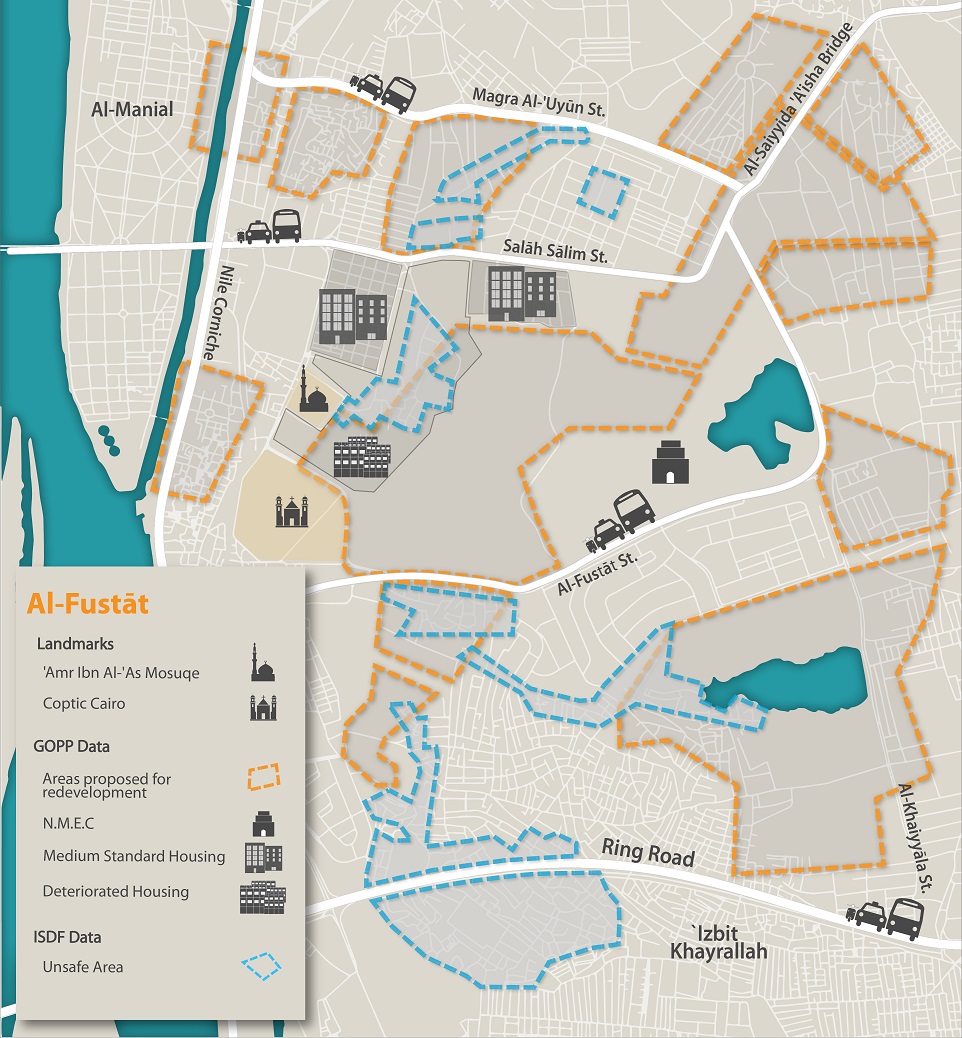

In October 2010 the General Organization for Physical Planning (GOPP) issued a Terms of Reference for a consultancy to prepare a “general strategic plan” for the Al-Fusṭāṭ area. The assignment included preparing detailed land-use options for various parts of Al-Fusṭāṭ, a task that was carried out by an Egyptian firm called CUBE Consultants.Cube Consultants’ 2010 master-plan for Al-Fusṭāṭ covers an area of 4000 feddans and its stated overall goal is to “realize the Cairo 2050 plan.” The area highlighted as the target for this intervention encompasses 4000 feddans that covers almost the entire Miṣr al-Qadīma district. This includes the populous informal area of `Izbit Khayrallah which hosts hundreds of thousands of inhabitants, and is also currently at the center of a series of court cases between residents and the Cairo governorate over ownership of the land. It is unclear how any plan could possibly be implemented on land which suffers from ambiguous ownership, which is the case for most informal areas, many of which lie within the scope of the plan.

This question is even more salient in light of the statement within the master-plan that one of its goals is to “improve the quality of life for residents by evacuating and developing some informal areas,” meaning that eviction is not only an option, but seems to be one of the key strategies of the proposed plan. Overall, the plan proposes to evict five informal areas, including the parts of ‘Izbit Khayrallah that have been categorized as unsafe.

These efforts are components of a proposed “Cairo Central Park” which is a series of parks to be constructed over the area proposed for redevelopment as depicted in the below image. The image also highlights the unsafe areas identified by Egypt’s Informal Settlement Development Facility in their latest (2013) report where thousands of residents currently live, as well as the NMEC discussed above.

This plan was proposed in 2010 in line with Cairo 2050 which had at that time begun to receive intense criticism from urban observers and citizens. After the 2011 revolution, Cairo 2050 GOPP officials began to almost dismiss the Cairo 2050 plan as “merely a dream.” New authorities in the succession of governments which followed then revised the plan, and finally resurrected it, renaming it the Cairo Strategic Urban Development Vision (CSUDV). It seems that the Al-Fusṭāṭ project also went through some revisions to make it more suitable to the new political environment and attitudes post 2011. The company’s Facebook page states that the project was revised in 2012 to ensure that it “achieves social justice” and that local NGOs were involved in the planning process. Although it does not say explicitly what measures were taken to ensure participation, a document published by the company and available online presents the results of a survey conducted with the residents of one part of the project area – namely, the so-called “City of the Dead.” The document does not state how many residents were interviewed or how they were chosen, but says quite clearly that 69% “want to leave and move to a different area.”

The measures taken to ensure social justice remain dubious at best, especially given that pictures on the company’s Facebook page still show snapshots of the originally proposed Central Park, meaning nothing has really changed.

The most recent information available is that Al-Fusṭāṭ is included within the CSUDV, the latest version of which is currently being disseminated by the GOPP. The only currently available CSUDV documentation mentions that Al-Fusṭāṭ is included in the vision, but the new strategic vision fails to provide any details about the planned interventions in the area. Participation and inclusion have been core mantras throughout the development of the CSUDV, but it is not clear if any such efforts have taken place, or are scheduled for the future, in the Al-Fusṭāṭ area. Furthermore, it seems that government bodies and consultants are under no obligation to disseminate their findings publicly (and explain them in plain language) across the affected communities.

While slogans such as social justice and participation, combined with photos of urban interventions in Europe such as this one, make for a nice fantasy of Al-Fusṭāṭ’s future, the implementation strategy is an entirely different story. The information available about what is taking place in Al-Fusṭāṭ right now paints a confusing picture that demonstrates a huge gap between “planned visions” of the area and consequences of these plans that are shaped by the power struggles and bureaucratic fights taking place on the ground, such as the ongoing dispute about which government entity has authority over Al-Fusṭāṭ’s land.

In September 2013 the Cairo Governor received an official notification from the GOPP that all of the Al-Fusṭāṭ area was under the purview of the NMEC project. However, the area is full of antiquities, which means it also falls under the authority of the Ministry of Antiquities (MoA). Accordingly, in March 2014 the newly appointed Prime Minister Ibrahim Mehleb sent a letter to the MoA requesting that the Ministry take all necessary measures to preserve the antiquities in the area, to which the MoA agreed. However, almost simultaneously, the Cairo Governorate sent forces to clear part of Al-Fusṭāṭ area and establish a park in its place, and stated that the Governorate owns the land. The problem with this park is that it would cause groundwater levels to rise, harming the antiquities in the area, according to official antiquities inspectors. In April 2014 the MoA acknowledged that the land belongs to the Governorate, but stated that it was currently trying to obtain a government decree to include the area in its list of heritage sites. This means that an area full of antiquities since around the 7th century is still not listed as a heritage site in 2014, and it also conflicts with the fact that the Prime Minister asked the MoA to protect the area’s antiquities. Later information clarified that while part of the land does fall under the Antiquities Preservation Law, the MoA had agreed with the Cairo Governorate to establish a park to protect the area, since many areas in Cairo that are left vacant are often used as garbage dumps by nearby residents.

This solution was proposed by a committee set up by Prime Minister Mehleb to study possible uses for the area. The committee consisted of the Cairo Governor and representatives from different ministries. The park was proposed as a temporary measure that may later be removed to allow for the preservation of any heritage sites. The committee also decided to plant cactus plants in the park to prevent the rise of groundwater. However, engineers and heritage experts argued that there was no way to avoid the rise of groundwater which has already harmed many parts of Miṣr al-Qadīma district (which includes Al-Fusṭāṭ) and is sure to have the same effect on the area.

In response to this information, the Head of Al-Fusṭāṭ Antiquities filed an official complaint to the Egyptian Anti-Corruption Agency arguing that heritage sites were being demolished in the area, after which he claimed he received threats from the MoA. In conjunction, the “Save Cairo” campaign filed a complaint to the General Prosecutor accusing the MoA and the Cairo Governor of destroying the historic city which has been officially designated a UNESCO world heritage site since 1979. In response to these complaints, the Cairo Governor issued an official statement in late April denying that any heritage sites had been demolished. After claiming that the Governorate saved the area from thugs and criminals who had invaded it, the Governor argued that those concerned with the area’s antiquities should thank the Governorate rather than attack it.

What We Don’t Know

What we don’t know about Al-Fusṭāṭ is who actually owns the land, and who has the authority to decide how to develop it without: 1) harming the area’s antiquities; and 2) violating the rights of the current residents. It is also difficult to understand if establishing the proposed park would in fact harm the antiquities or not, since heritage activists say it will while the MoA says it will not. In general it is unclear whether there is a way to avoid damaging the area’s antiquities, and whether the park is, in fact, the most logical way to protect the area. In addition to this, it is unclear how the plan will affect Al-Fusṭāṭ’s current residents, and to what extent their interests and opinions have been solicited and integrated into the existing plans for the area. Finally, as mentioned before the GOPP included the area in its CSUDV, but gave no details about what is actually planned for the area. The GOPP’s plan may or may not match the policies which the Cairo Governorate and MoA are currently carrying out, and this vague relationship only serves to increase the ambiguity of the situation.

What we do not know either is how public funds are being spent on plans such as the GOPP’s strategy for the area which will force the eviction and relocation of a significant number of residents living in the area, although the GOPP still claims its commitment to ‘Social Justice.’ This plan was not only produced by the GOPP, but it is also promoted by the Ministry of Investment as a tourism investment opportunity under the name “Al-Fusṭāṭ Area Development.”

This ambiguity and confusion not only affects the residents of Al-Fusṭāṭ and Cairo in general, but also affects the development of the area itself, as the unrelenting disputes among government entities impact the feasibility, effectiveness, and goals of new urban plans, if basic issues such as land ownership and bureaucratic authority and cooperation among entities have yet to be resolved.

This messy situation could potentially be solved if the relevant state agencies provided adequate information in a transparent and accessible way to all concerned parties. Transparency and information-sharing is not only important to ensure participation, but it can actually make a project stronger and more efficient by avoiding time-consuming disputes such as those occurring in Al-Fusṭāṭ. This can also enhance the democratic management of the city and ensure that there are more representative and useful ties between municipal, governorate, and national levels. This is important not only to guarantee that the interests of different groups (communities, civil society actors, and the commercial sector) are represented, but also that responsibilities for implementation, monitoring and evaluation are clearly delineated.

Featured Photo (source: Cube Consultants Visionary Architects Planners)

Hisham Fahim Says:

وافق مجلس الوزراء على قبول العرض الفني والمالي المقدم من تحالف التنمية العمرانية (+5) الإستشاري، للقيام بإعداد المخطط العام للعاصمة الادارية الجديدة.

ويتضمن العرض المقدم من التحالف أعمال المرحلة الأولى من المخطط العام للمدينة ككل بمساحة 170 ألف فدان، بقيمة 9.2 مليون جنيه، وكذلك أعمال الأسبقية الأولى التي تتضمن المرحلة الثانية الخاصة بتطوير الأعمال والثالثة الخاصة بإعداد المخطط التنفيذي والرسومات التنفيذية ومستندات

October 28th, 2015 at 9:01 pmالطرح.

تحالف التنمية العمرانية (+5) الإستشاري

تامر الخرزاتى -أوكوبلان

اشرف عبد المحسن – كيوب

ايمن عاشور – اركبلان

و اخرون