Coming Up Short: Egyptian Government Approaches to Informal Areas

Informality has reshaped the form and nature of Egyptian cities over the past several decades and will continue to do so for years to come. The government has adopted a range of policies and legislation to slow or halt the growth of informal settlements, but successes in improving or removing informal areas have been limited to specific communities and have done nothing to reduce the overall growth of informal areas.

How many informal areas are there in Egypt? No one knows for sure. In Cairo, the city in which the extent of informal areas is best known, the Ministry of Housing estimates that 40 percent of the population lives in informal settlements. A comparison of census data between 1996 and 2006 puts the number at 67 percent (Sims 2012), with the percentage increasing since the 2011 Revolution. In the rest of the country, much less is known. In Alexandria, David Sims, a long-time urban practitioner and observer of Egypt, estimates that at least 40 percent of residents live in informal areas. In some of the smaller cities in Upper Egypt and the Delta, the percentage is much higher (Sims 2013). Yet another source of information, the Informal Settlements Development Facility (ISDF), estimates that 75 percent of urban areas in cities and villages throughout Egypt are unplanned and one percent are unsafe (ISDF 2013).

Regardless of the discrepancies in statistics, the extent of informal areas is significant. The government’s approach to informal settlements in the decades to come will have broad implications for the future of cities throughout the country. The government’s approach to informal areas also illustrates the government’s philosophy of cities, what they believe a city should be, who they believe belongs in the city, and who should have a say in how the city is built.

How can the national approach to informal areas continue to evolve to be more accommodating of informality? What can the government learn from its own experiences with informal areas? And what can the government learn from the experiences of other countries to help fulfill their constitutional obligation to “improve the quality of life and public health” in informal areas (GoE 2014). This article discusses past and current government strategies for informal areas as well as the impact of these policies. It also looks at several examples of the way other countries have addressed informal areas in their cities.

Approaches to Informal Settlements in Egypt

Article 78 of the 2014 Constitution recognizes ‘ashwai’at (the literal translation of which is random or unplanned areas) and requires the government to take steps to improve them.

The State shall also devise a comprehensive national plan to address the problem of unplanned slums, which includes re-planning, provision of infrastructure and utilities and improvement of the quality of life and public health. In addition, the State shall guarantee the provision of resources necessary for implementing such plan within a specified period of time (GoE 2014).

In June 2014, President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi created the Ministry of Urban Renewal and Informal Settlements (MURIS), which according to Presidential Decree No. 1252/2014, will be the institution responsible for the implementation of this constitutional article.

The article is somewhat problematic as it does not include a definition of the term ‘ashwai’at (translated as “unplanned slums” in Article 78 quoted above) other than to say that ‘ashwai’at are a “problem.” From the article, we can assume that these unplanned areas require planning, they may lack infrastructure and utilities, and residents may have a comparatively low quality of life and experience higher risks to public health than residents in planned urban areas. First, this perspective is narrowly focused on low-income areas and fails to consider the unplanned, un-zoned, unregulated, or un-enumerated areas that may lie within middle or upper class areas. Furthermore, the meaning of the term ‘ashwai’at is not shared consistently among government entities or the general public. The 2008 Building Law avoids the term altogether and instead refers to unplanned areas (al-minātiq ghaīr al-mukhaṭaṭa), Presidential Decree No. 305/2008 refers to unplanned areas and unsafe areas (al-minātiq ghaīr āmina), and the aforementioned Presidential Decree No. 1252/2014 uses the same language as the Constitutional Article above.

Despite the ambiguity of Article 78, the inclusion of informal areas in the Constitution is part of a broader shift in the government’s approach toward informal settlements over the past several decades. In the late 1970s and 1980s, the government largely ignored informal urban development, hoping the problem would quietly go away (Sims 2012). When this did not happen, the government adopted an aggressive interventionist approach in the 1990s and early 2000s. Today, the government accepts informality as a part of the city and uses language of participation and public health and safety in their policies concerning informal areas, but often their rhetoric does not match their action. For example, the government still takes aggressive steps to ‘remove’ informal areas when necessary (Amnesty International 2011). This gradual shift in policy was driven by several factors, including the scale of informality eclipsing the capacity of the government to manage it, political expediency, security concerns, electoral contests, and the ongoing civil discourse that has demanded a more humane, inclusive, and open approach to the residents who live in informal settlements.

The Government’s Approach

There are two major principles that underpin the government’s approach to informal areas and urban development in general. The first is that informal areas are a problem. They are identified and characterized negatively and treated as something that must be reduced or removed, much in the way that the government plans and acts to reduce illiteracy, poverty, and child mortality rates. The second principle is that urban growth must be directed away from existing cities and agricultural land to desert areas in order for Egypt to develop properly and enhance economic growth. An often-cited statistic is that Egypt utilizes just four percent of its land area (Mitchell 1991, Sims 2012).

Informal areas fall primarily under the jurisdiction the following government entities: the Ministry of Housing, Utilities and Urban Communities (MHUUC), the Governorates, the Informal Settlements Development Facility (ISDF), and the newly established Ministry of Urban Renewal and Informal Settlements (MURIS).1 Their roles in the regulation of informal areas will be detailed in the narrative below. The Supreme Council of Planning and Urban Development (SCPUD) is not directly involved with informal areas, but governs urban development in general. SCPUD sets national-level goals and policies for planning and urban development, coordinates between the government entities that are concerned with urban development, provides expertise to legislators about laws governing urban development, evaluates the implementation of the national strategic plan and the regional strategic plans, and approves the national, regional, and governorate strategic urban development plans (Nada 2011).

There are two types of approaches that the government takes to informal areas: preventative approaches that are meant to limit informal growth and interventionist approaches in which the government either improves or removes informal areas. It is important to note that, in practice, these two types of approaches are only applied to a fraction of informal areas. Many informal areas have access to public services and utilities and have relatively strong, if not formal, land tenure. This is not to suggest that informal areas are treated on equal terms with their formal counterparts: the quantity and quality of public services available in informal areas is, on the whole, inferior to those offered in formal areas. Government planners and decision makers have long recognized that informality is a fact of life in cities. As important as the question of how the government deals with informal areas is the question of when it deals with them. This section will attempt to answer both questions.

Preventative approaches

Preventative approaches include “belting,” delineating and enforcing urban growth boundaries (UGB), bans on using agricultural land for residential purposes and squatting on state-owned desert land, and using building codes and planning regulations which, when enforced, prevent the types of structures that are built in lower-income informal areas.

Belting is a planning technique in which informal areas are surrounded by planned areas to halt their outward expansion. The government formalized this approach to informal areas in the Informal Settlements Belting Program which lasted from 2004 to 2008 (El-Shahat and El Khateeb 2013).

Urban growth boundaries (UGB) are regional boundaries used to delimit the future growth of a city by encouraging growth in some areas, typically within the boundary itself, and discouraging or banning growth in others. UGBs are used to restrict low-density urban sprawl, preserve green spaces, and encourage higher density development in a given area. In Egypt, UGBs are used primarily to limit informal development on agricultural land. Law No. 119 of 2008 (the Building Law) authorized the use of UGBs as a tool to be used in creating strategic city plans (Nada 2011).

Article 970 of the Civil Code forbids building on state-owned desert land. In the case of “infringement” the mandated minister has the right to remove “infringements.” Article 26 of the 1979 Law on Local Government also gives the Governor the power to protect “both public and private properties of the state and remove any infringements administratively” (Amnesty International 2011).

As for agricultural land, the first attempts by the government to regulate the development of peri-urban farmland came in 1978 through a series of laws and decrees (Sims 2012). Informal development of agricultural areas continued unabated and the government responded with increasingly strict regulations, including a military decree in 1996 that made the illegal development of agricultural land a criminal offense (USAID 2010). The 1996 decree was abolished in 2004 and law No.116 of 1983 has since served as the instrument through which the government protects agricultural land. According to this law, any building constructed on agricultural land or any community efforts to subdivide agricultural land for building purposes is illegal (El-Hefnawi no date).

Despite the UBGs and the bans on the development of agricultural land, most informal growth occurs on farmland on the periphery of urban areas. Agricultural land is privately owned and the transaction costs of land acquisition and development are relatively low and these areas have reasonable access to existing amenities and public services of the city. The alternative for the natural expansion of the city would be to move outward into state-owned desert land, which is not for sale. Further, squatting on state-owned desert land is very risky because the probability of demolition is much higher than demolition in agricultural areas (Séjourné 2009).

Bans, UGBs, and belting are used to prohibit or restrict where informal areas are built. The National Building Code and its design standards are used to prohibit or restrict the types of buildings, building densities, or population densities typically found in lower-income informal areas. These codes and regulations provide minimum standards for building heights, bulks, set-backs, building to land ratios, open space, accessibility, street widths, building materials, engineering standards, etc. for new buildings or neighborhoods. The Housing and Building National Research Center (HBRC), affiliated with the MHUUC, is responsible for the national building code. It also produces infrastructure codes, building work service codes, environmental engineering codes, and architectural concepts (such as housing and planning design) (Salama 2006).The General Organization for Physical Planning (GOPP), also affiliated with the MHUUC, is responsible for planning regulations and working with local authorities to create their city strategic plans. When preparing local city plans, authorities are able to set higher standards for their building codes and planning regulations, but they may not cross the minimum threshold and they must also corroborate with the higher level national and regional plans. The governorates are responsible for enforcing codes and regulations (GoE 2009).

Preventative policies have not been successful in limiting the growth of informal areas. At best, they have redirected informal growth from one area to another or at worst, they have encouraged informal growth, left residents unprotected, and increased corruption at the local level. For example, the national building standards produced by the HBRC are suitable for mid- to high-end housing units, but do not accommodate the types of buildings that lower income families can afford. In order to satisfy this demand, these standards force developers to work informally. Developers know that if they build units that meet the national building codes, their targeted clientele will not be able to afford them (Nada 2011). Local government officials responsible for enforcing the building code and issuing building permits also know that the regulations do not always meet the local context and sometimes use them as leverage for rent-seeking. The result is that the regulations are ignored, no minimum standards for safety or security are enforced, and the welfare of residents suffers. While this allows the informal sector to meet the high demand for affordable housing units in Egypt, sometimes the buildings are unstable, poorly built, and unsafe for use. In these instances, the building code benefits local government officials and developers and is harmful to residents—the very people it is meant to protect.

Interventionist approaches

Interventionist approaches include eviction and demolition, resettlement, rehousing, and upgrading. How does the government decide where to intervene and how to intervene? Two government entities have the authority to intervene in informal areas: the governorates and the ISDF. The ISDF will be under the jurisdiction of the newly established Ministry of Urban Development and Informal Settlements.

The Informal Settlements Development Facility

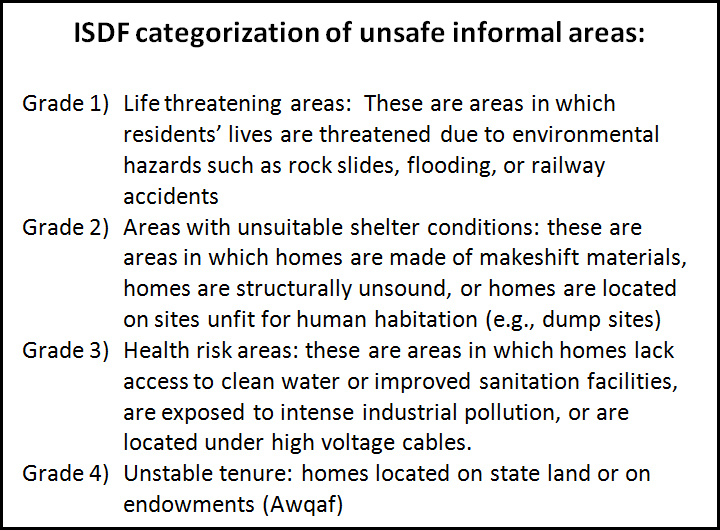

The Informal Settlements Development Facility (ISDF) was established in 2008 by presidential decree in the wake of the Duweiqa rock fall which killed approximately 110 people living in an informal settlement at the base of the Moqattam cliffs in Cairo. The ISDF’s approach to informal areas is relatively straightforward. They conduct an annual review of all of the informal areas in the country and designate areas that meet certain criteria as unsafe or unplanned. Any informal area that the ISDF identifies as unsafe may be subject to further interventions by the ISDF”.  All other informal areas are left to the jurisdiction of the governorate. These unsafe areas are given a grade from 1 to 4, where Grade 1 designates the areas that are most dangerous to the health and safety of its residents and Grade 4 is the least dangerous. This grading hierarchy serves to prioritize ISDF interventions in informal areas. (See sidebar for details). According to their 2010 report, residents living in Grade 1 areas will be resettled to a neighboring or nearby area. Grade 2 areas will either be resettled, rehoused, or the building stock will be upgraded. In Grade 3 areas, the government will address the public health issue by either upgrading public services or utility networks or by mitigating pollution from nearby factories, for example. Residents in Grade 4 areas will begin negotiations with the government to regularize the tenure of their land.

All other informal areas are left to the jurisdiction of the governorate. These unsafe areas are given a grade from 1 to 4, where Grade 1 designates the areas that are most dangerous to the health and safety of its residents and Grade 4 is the least dangerous. This grading hierarchy serves to prioritize ISDF interventions in informal areas. (See sidebar for details). According to their 2010 report, residents living in Grade 1 areas will be resettled to a neighboring or nearby area. Grade 2 areas will either be resettled, rehoused, or the building stock will be upgraded. In Grade 3 areas, the government will address the public health issue by either upgrading public services or utility networks or by mitigating pollution from nearby factories, for example. Residents in Grade 4 areas will begin negotiations with the government to regularize the tenure of their land.

The ISDF also implements socio-economic programs that focus on women’s health, job opportunities for youth, adult literacy, reducing drug addiction, savings and loan programs, and school construction. Yet, the government does not provide easy access to information about where particular interventions or programs take place. It is also unclear how these programs differ, complement, or overlap with other government or internationally sponsored programs. For example, some of these ISDF programs overlap with those of the Social Fund for Development (SFD), which is a national governmental organization (funded by the World Bank) chaired by the Prime Minister, and meant to address unemployment and poverty. The SDF focuses primarily on small and medium enterprise (SME) development, but under their broad mandate, they also have a wide-array of projects in health, education, job training, community development, infrastructure, and environmental services, among others.

One the major challenges to understanding the work of the ISDF is access to information. The ISDF used to publish information delineating the status of unsafe areas on their website, but they stopped doing this when a new ISDF executive was appointed in January of 2013. As a result, residents and other actors have no idea of the government’s plans for their areas. An area may be slated for demolition or an area may be targeted for upgrading without any formal or informal communication of this new status to its residents, nor public knowledge about it. Sometimes people’s homes are demolished without prior notice, communities are not consulted about the ISDF’s plans, and residents are not given written eviction orders (Amnesty International 2011).

The ISDF’s approach to unsafe areas is also inconsistent and problematic. The grading system discussed above gives the impression of a clear and rationalized approach to unsafe areas in which the government would intervene first in the areas in which residents lives are at stake (Grade 1), followed by Grade 2 areas, and so on. However, this has not always been the case. In some areas, residents living in areas with poor quality housing (Grade 2) are being evacuated before residents living in life-threatening areas (Grade 1), leaving residents at risk. Furthermore, sometimes the government displaces families leaving them either homeless, unable to earn a living, or subject to other human rights violations (Amnesty International 2011).

One of the challenges the ISDF faced was their position within the government hierarchy. Like the SDF, the ISDF was under the direct control of the Prime Minister and did not have the full weight of a ministry behind it. They struggled to obtain the required financial resources to implement their plans (Nada 2014) and were subject to interference from the army (Farid 2014). Now that the ISDF will be under the jurisdiction of MUDIA, they may have a stronger foundation on which to stand.

Governorates

The majority of informal or unplanned areas under the jurisdiction of the governorate do not receive special attention. They are included in national, regional, and local plans that are made by the GOPP and local authorities. The governorates do not have a formal policy toward informal areas which, in some way leaves them more vulnerable than the unsafe areas classified by the ISDF. Informal areas on high-value land are especially vulnerable for eviction, resettlement, or rehousing. For example, two areas close to downtown Cairo, the Maspero Triangle and Boulaq, have been targets of major redevelopment projects for many years.

GIZ has been working with the GOPP to develop a more participatory approach to planning and urban development. As part of their Participatory Development Program in Urban Areas, GIZ established Urban Upgrading Units (UUU) in Cairo, al-Gīza and al-Qalyūbiyya governorates to serve as a focal point for government interventions in informal areas. They serve to coordinate the efforts of the ministries, local administrations, and civil society. As of this writing, they are working with the government to expand the UUUs to the rest of the governorates in the country.

RESETTLEMENT

Resettlement is the process through which residents are relocated from one area of a city to another, usually at some distance from the original location. Residents vacate their homes, the homes are destroyed, and residents are given new apartments in public housing blocks, usually at low rates of rent. Resettlement can either be voluntary or forced. Voluntary resettlement is when citizens agree by their own volition to the conditions of relocation proposed by the government. Forced resettlement is when residents have no choice in the resettlement process. Forced resettlement is usually preceded by forced eviction, whereby citizens’ homes are destroyed and residents are displaced from their neighborhood by security personnel (Patel 2013).

International best practices for involuntary resettlement dictate that 1) resettlement should be minimized and used only as last resort; 2) where displacement is unavoidable, residents should be compensated for the full replacement cost of their properties; 3) the government should provide moving assistance and support during the transition period from their old home to the new; 4) the government should provide assistance to families until they are able to achieve their former standards of living and reestablish their ability to earn a steady income (Miranda 2014).

As stated above, the ISDF is responsible for identifying the unsafe areas that will be ‘removed’ and its residents resettled. Evictions are carried out by the governorate and the ISDF in coordination with the armed forces and security personnel if necessary. The governorate is responsible for site demolition and clearance, the construction of the new apartment buildings as well as public service provision in the new area. While areas designated as unsafe by the ISDF are under threat of removal, at the very least, according to ISDF’s own policies, these areas will be resettled (although the ISDF’s record of resettlement is inconsistent). If the governorate chooses to forcibly evict a community that is not designated as unsafe by the ISDF, that community is not entitled to resettlement and typically does not receive adequate compensation for the loss of their property (Amnesty International 2011).

Impacts of Resettlement

The government often prefers resettlement as an approach to informal areas because they are then able to develop and benefit from the newly cleared land (except in the case of land unsuitable for development). However, the government also believes that resettlement has a positive impact on residents. They are resettled in higher quality housing units with strengthened security of tenure in modern neighborhoods away from environmental hazards. What is there not to like?

This policy is a limited, problem-focused perspective. The government sees the limitations of the informal area—poor housing conditions, environmental hazards, over-crowding, etc.—and sees resettlement as a solution to those problems. However, this perspective fails to acknowledge the positive aspects of the communities targeted for resettlement such as their social ties, access to transportation, commercial areas, previous investment in their neighborhood, and public transportation. This perspective also homogenizes communities, using the household as a unit of analysis. A household with two parents and two children with a stable, mid-level income living in a 100m2 home is treated exactly the same as a female-headed household with four children and unstable income living in a 40m2 apartment. A household with a bread-winner who works downtown is treated the same way as the bread-winner who relies on the community economy for income.

Communities slated for resettlement are home to some of Egypt’s most vulnerable and poorest urban citizens. Although the government may see resettlement as helpful and beneficial to these communities, they may be making the poor poorer still. Rather than improving the living condition of low-income residents, resettlement often perpetuates poverty by destroying the socio-economic foundation of communities. Most resettlement sites are located on the outskirts of urban areas far from job opportunities, commercial areas, and they lack public transportation. As a result, many residents who are resettled leave the better housing units behind and move back to the informal areas of the city perhaps to be resettled again at a later date.

A 2009 study of slum resettlement in Delhi and Mumbai, India demonstrated the economic burdens of resettlement on resettled populations. The income of resettled households decreased, their overall unemployment rate was higher—especially among women—and overall household assets declined. As a result of the loss of income, overall household expenditures decreased. Families spent less on necessities such as food, clothing, and education, as well as entertainment while expenditures for travel, health, and utilities increased (Khosra 2009). The reduction in food and education expenditures may have a severe long-term impact on the human development of residents, especially children (INP 2000, Victora, et al. 2008).

There is no such study examining the socio-economic impact of resettlement in Egypt, but if any of these findings hold true for resettled communities in Egypt, and we have reason to believe so, there is a major cause for concern. For example, the resettlement site Masākin Osmān is located on the outskirts of 6th of October City between the Southern Neighborhoods and the October Cemeteries on the Giza-Wahat Road. When completed, the 200 feddan site is expected to have 762 buildings, with about 18,000 apartments and a population of approximately 75,000 people.2 As of 2011, there were about 14,000 people living there. Many residents were resettled from central Cairo, almost 40 kilometers away (some by the ISDF despite their policy to relocate residents to “nearby or neighboring areas” from their original housing site) (ISDF 2011). There are no transportation linkages for the community and just one public service building—a health clinic that remains locked, empty, and unused as of this writing. Commercial space was not considered in the original site plan and whatever stores exist were built by residents themselves after arriving. Job opportunities in the area are extremely limited.

The resettlement site of Masākin Osmān in 6th of October City. Notice the physical adaptations of the residents to provide commercial space for the neighborhood. © Tadamun

Improvements in Resettlement

Resettlement should be used in rare circumstances when all other options are exhausted and resettlement should never be forced. If the intent of the resettlement program is to improve the lives of residents living in unsafe areas, the benefits of resettlement should be understood by the residents themselves. Residents should be notified with full disclosure about the government’s intent to resettle them, their timeline, and residents should participate in planning and executing the resettlement process. They should have a choice as to where they are resettled, including at least one option in a neighborhood that is close to their original homes. As with rehousing, the government should ensure that the expense of the new housing does not exceed the capacity of residents’ ability to pay and they should also ensure that the new housing units meet minimum safety and construction standards. Resettlement sites should have adequate services before anyone is resettled there. The sites should have access to public transportation and access to employment opportunities. Residents should also be supported during their time of transition from their original housing site to the resettlement site.

REHOUSING

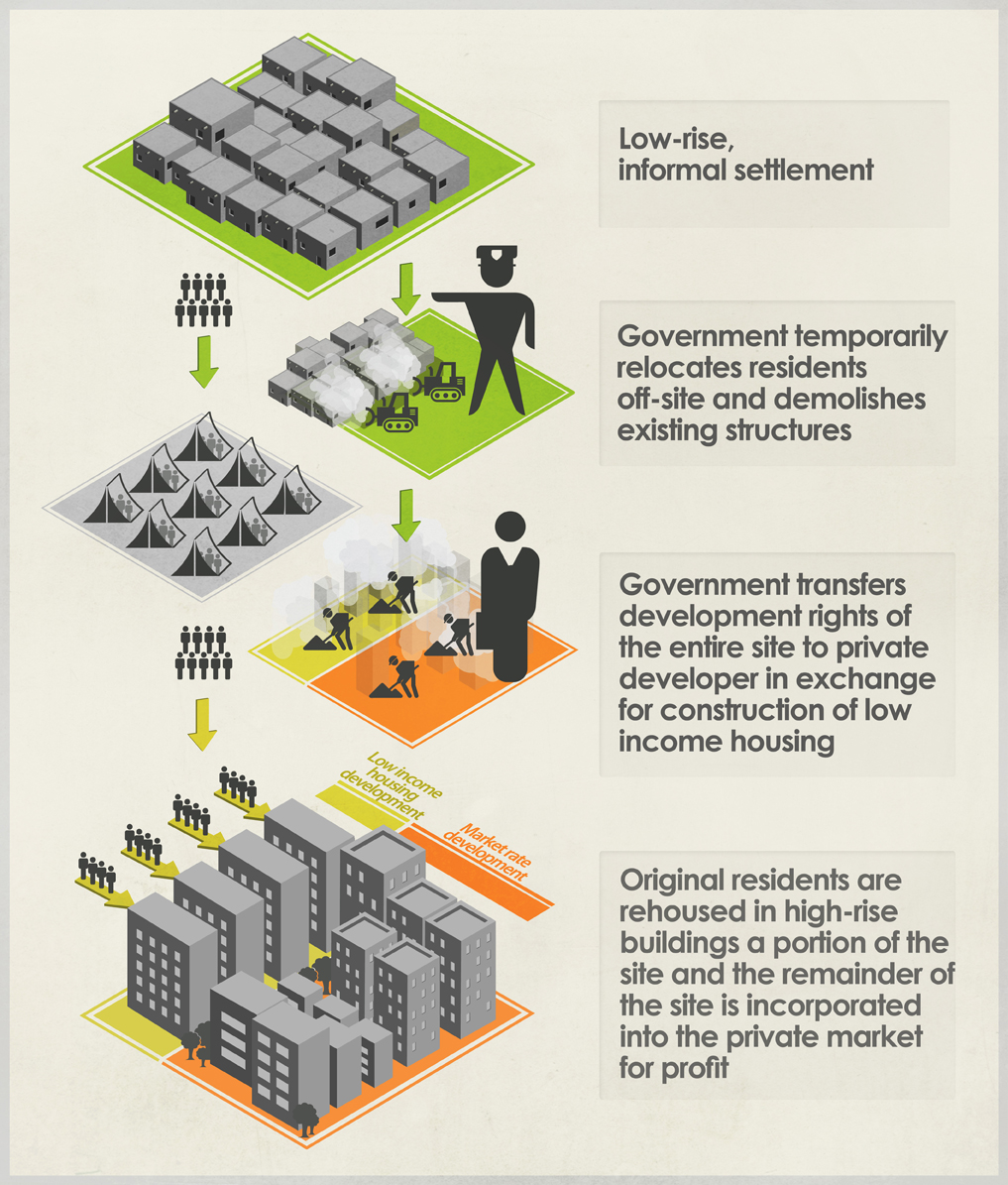

Rehousing is an approach to human settlements in which the government temporarily houses a community off-site, clears an existing settlement and builds new apartments on the same land that are given to the original residents (Patel 2013).

There are two forms of rehousing. The first form of rehousing is done entirely by the government using public funds. Residents are temporarily relocated off-site, new public housing structures are built on the full extent of the original site, and the residents are either given the units or the government provides subsidized loans or rents. An example of this is the Zinhum rehousing project.

The second form of rehousing involves both the government and a private developer. In Egypt and other countries with large informal settlements or slums, the government sees this type of rehousing as a no-cost approach of urban development and a way to attract new investment to low-income urban areas and “unlock” the latent value of the land. How does this work? The form of the existing settlement is important. A community targeted for rehousing intervention is typically comprised of low-rise, ground-level structures. If the same community lived in high-rise buildings, the same population could live on a fraction of the land of their existing neighborhood.

A public-private rehousing project is a three step process. After identifying a community for the rehousing intervention, the government houses the community’s residents in temporary shelter off-site and demolishes the existing buildings. The government then gives the development rights of the cleared property to a private developer in exchange for building new apartments for the original residents on the same site. The private developer typically gives these buildings to the government to either sell or rent to the community. The private developer may develop the remaining portion of the site as they wish and sell or rent the properties at market rates for profit. In a city like Cairo where real-estate in close proximity to downtown is a scarce commodity and very expensive, investors are eager to build these kinds of developments because, as soon as the community is moved to high-rise apartments, upwards of 90 percent of the land can be opened for private development, creating the potential for large profits (Giridharadas 2006).

Public-Private Form of Rehousing

The public-private rehousing approach is lauded by the government as a win-win solution for some informal areas: these projects provide good housing for people who cannot afford market rate units, it promises high returns to large developers, and does not cost the government anything—all of the development costs are borne by the developer. Furthermore, the development expands the tax base of the community and promises higher property tax returns in the long run. However, this no-cost rehousing approach only works where expected property values are high enough for developers to take on the project. Public-private rehousing programs are driven by two related objectives. First, the government accomplishes their goal of removing blighted, unsightly, or poor neighborhoods while avoiding the controversy that accompanies resettlement. Second, the value of these neighborhoods is “unlocked” and open to the formalized real-estate market where higher value uses can be built to promote economic development. However, the approach is highly contentious. In essence, by giving away development rights to developers in exchange for low-income housing, the government is transferring the present and potential wealth of low-income communities to developers and, ultimately, higher-income residents. While upgrading projects (see below) may result in some gentrification of a low-income neighborhood, rehousing essentially gentrifies an area outright, leaving only a fraction of the area to the low-income residents.

Although rehousing does not have the distance challenges that resettlement does, it does have a significant impact on the community. Like resettlement, rehousing disrupts the economy and social networks. The majority of informal area economies are rooted at the ground-level either as stores, workshops, or other services. The community cohesion, networks, self-organization structure, and emotional support systems are also directly tied to this type of low-rise development. As a result, the new high-rise communities tend to be weaker, crime may increase, people may spend less time outside, and opportunities for jobs, shopping, or access to other services decreases overall. While rehousing may improve the quality of housing in these areas, the overall quality of life sometimes deteriorates and the government must ensure that proper services are offered to mitigate these negative impacts.

In rehousing schemes, there are also concerns about public services and their cost to the lower-income residents. Egypt’s urban infrastructure is already under heavy strain—an increase of higher-value land uses and increased density overall will only increase this strain. Furthermore, the costs of maintenance of high-rise buildings are much higher than in ground level developments. For example, a broken pipe in a tower requires hiring a professional to fix it whereas in an informal area, fixing a broken pipe is commonplace and inexpensive (Giridharadas 2006).

In some situations, rehousing may be an appropriate approach to informal areas. However, the determining factor should not be private real-estate considerations. The determining factor should be the needs of residents expressed by residents themselves balanced against issues of public health and the general welfare of the community. Finally, residents should be the primary beneficiaries of the rehousing intervention.

UPGRADE/REHABILITATION

Upgrading or in-situ development is the gradual improvement of existing buildings and infrastructure within an informal settlement to an acceptable standard over time without demolishing the urban fabric or displacing residents to another site or elsewhere on the site (Del Mistro and Hensher 2009).3 The objective of upgrading is to rejuvenate an existing community with minimum physical and social disruption. Upgrading covers a wide range of possible interventions. Minor upgrades include improving street-lighting, leveling street surfaces, or painting homes. Major improvements include the installation of natural gas infrastructure, the extension of the sanitation network to each home, the provision health facilities, schools or other significant public services, or renovating a significant number of buildings (Patel 2013).

There are three main stages of upgrading an informal settlement (Choguill, et al. 1993).

1) Primary level services which address a community’s basic health needs

2) Intermediate level services which are socially and culturally accepted levels of service

3) Ultimate level services which are those services that are provided for the convenience of residents

Upgrading is widely considered an international best practice for improving informal areas. Upgrading minimizes the direct impact on the local economy and, for the most part, leaves communities intact.4 It is less costly than either rehousing or relocation and can make an immediate, highly visible improvement in communities. (Upgrading is also the best way to ensure that the targeted community actually benefits from the project and it can mobilize local investment or attract outside investment.)

In Egypt, upgrading is quite common and does not necessarily fall under a formalized community improvement program. Many informal areas receive de-facto government recognition when the government installs utility networks or provides them with other primary or intermediate public services. In the early 1980s, USAID sponsored a nation-wide, market-based water and sanitation infrastructure program. Because the program was market-based,

both formal and informal areas were eligible for the program as long as they were able to pay. The first government program for upgrading low-income areas was launched in May of 1993 as a response to the spread of religious movements in informal areas. The program included upgrading electricity, water and sanitation infrastructure, street paving, and landscaping. This program did not provide space for any community participation and also called for the clearance of twenty-five deteriorating areas in Cairo and Alexandria (El-Batran and Arandel 1998).

Upgrading of this sort continues today. The ISDF announced its most recent informal settlement upgrading program in January, 2014. With an estimated cost of EGP 350 million, the program will upgrade water and sanitation infrastructure, establish fire-fighting networks, install street lighting, and pave roads in thirty informal settlements in Cairo and Giza governorates. Typically, the ISDF is responsible for the planning and management of upgrading projects and implementation is carried out by the governorates. However, this most recent program will be implemented by the army because, according to a statement from the cabinet, the projects “require high expertise” (Farid 2014). These ISDF interventions and other government service provision programs run into problems because they do not involve the community.

There are several factors required for in situ development to be successful. Foremost is community “buy-in.” The community must invest both time and money in both the formation of the project as well as its implementation. Security of tenure must be guaranteed to community residents. If residents feel they will lose their property, they will offer stiff resistance to any effort to develop the area. Outside of philanthropic organizations or individuals, private investors must have a way to recover the costs associated with development (Choguill 1999 in Del Mistro and Henser 2009).

Over the past several decades, international best practices of informal settlement or slum upgrading programs have evolved from purely physical interventions to physical interventions that also include social programs and involve public participation in every stage of planning and implementation while keeping forced evictions and resettlement to an absolute minimum.

Here are a few examples of successful upgrading programs from around the world that represent this evolution.

Examples of Upgrading Projects in Other Countries

Kampung Improvement Program, Jakarta, Indonesia

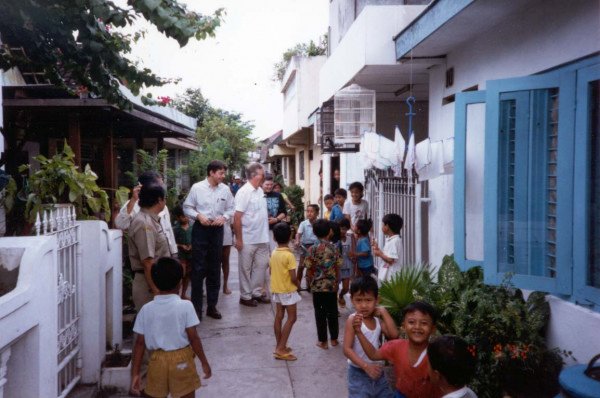

The Kampung Improvement Program was an urban upgrading program that began in 1968 in Jakarta and Surabaya spread to nearly 800 cities throughout Indonesia.5 The program’s goals were to improve the living environment and quality of life of as many of Jakarta’s poorer residents as possible, to minimize disruption of the communities’ social and economic ties, and to expand the productive capacity of residents so that they may increase their incomes and contribute to the development of the country, all while spending as little money as possible. The program was at first, focused on physical improvements of communities and included building access roads, bridges and footpaths; water and sanitation infrastructure; and social buildings, schools and health clinics. The program assumed that by providing basic infrastructure and public services, residents would be more likely to invest in their homes. The city government worked with each community through a Kampung Committee, which was responsible for establishing improvement priorities and liaising with communities. Local contractors competed in open tenders to construct the projects. The program evolved to integrate social components as well.

One of the lasting impacts of the program was its influence on local government. When the program was first begun, urban planning throughout Indonesia was highly centralized as it is in Egypt, but as the program expanded to more cities and the administration of the program become more complex, it forced the government to devolve implementation responsibilities to the municipal level of government (AKAA 1980, Dhakal 2002).

Upgraded housing as a result of the Kampung Improvement Program in Indonesia. ©World Habitat Awards.

Urbanization Program for Popular Settlements in Rio de Janeiro (PROAP II) or Favela-Bairro II, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

The Favela Bairro II (Slums to Neighborhoods) project was the second of a three-part slum upgrading program that began in 1995 in Rio de Janeiro. The project was funded by a US$180 million loan from the Inter-American Development Bank and US$120 million commitment from the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro. The purpose of the program was to improve the quality of life in low-income settlements by investing in infrastructure and social programs. The program also had programs targeted at youth, employment, and income generation as well as capacity building programs for local government officials. The program was created when the government realized that eviction, demolition, and resettlement programs that placed residents in large public housing blocks far from the city center was not an effective strategy to address informal areas.

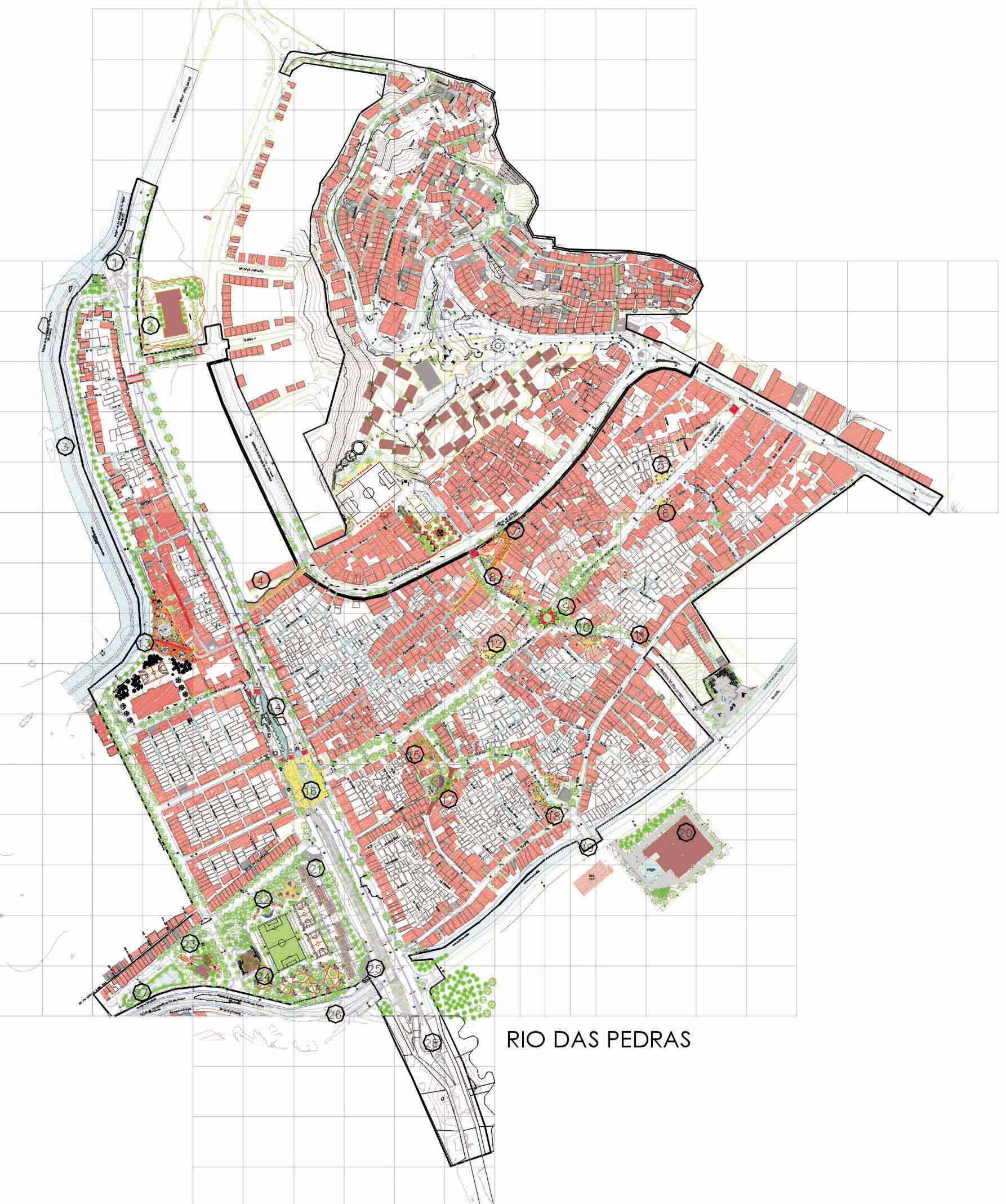

The program reached about 76,000 families in 62 different informal settlements. Residents participated in every aspect of the program’s planning and implementation. Like the ISDF approach in Egypt, the Favela Bairro project started by surveying all of the favelas (slums) in Rio de Janeiro, and was largely a top-down upgrading initiative, but residents participated in every phase of planning and implementation of the project. The program did not, as its title may suggest, turn slums into formalized neighborhoods, but it played a large part in institutionalizing the in-situ approach to urban upgrading and establishing residents’ right to live where they choose (Magalhães and di Villarosa 2012).

The national context of the Favela Bairro projects is worth discussing. In 1988, Brazil became the first country in the world to include a chapter on urban policy in their constitution. The chapter includes just two articles: one recognizing the social function of property and the other recognizing squatters’ rights. These articles were by no means the beginning of an urban consciousness in Brazil, but were the result of several years of work by the National Urban Reform Movement and prior pro-poor, pro-democracy social movements supported by labor unions, civil organizations, residents’ associations, and the progressive branch of the Catholic Church steeped in liberation theology (Fernandes 2010).

Over the next decade and a half, local governments became increasingly democratic and independent of the central government and were able to design and implement projects to address their city’s needs. In a sense, the decentralization of government authority paired with a national consciousness that prioritizes urban equity and supports the Right to the City, allowed Brazilian municipalities to become a laboratory for urban innovation and democratic management. The Favela Bairro projects in Rio de Janeiro are but one series of projects that have been implemented throughout the country.

An upgrading plan for the Rio das Pedras favela in Rio de Janeiro that was part of the Favela-Bairro program.

Baan Mankong Collective Housing – Thailand

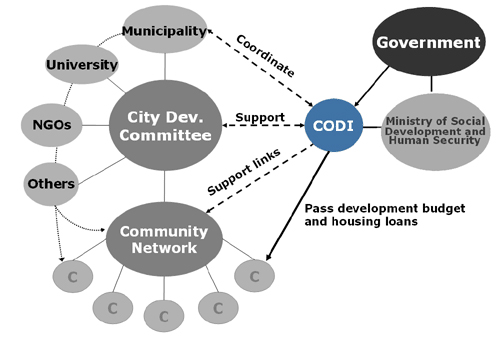

The Thai government launched the Baan Mankong Collective Housing program in 2003 to address the housing problems of the country’s low-income citizens. The program provides community subsidies for infrastructure as well as loans for housing and land. Unlike most conventional low-income community improvement loan programs, the loans are not given to individuals but instead to community organizations to improve housing, environment, public services, and tenure security. By lending to the community organizations, the government is able to leverage the assets of the community and existing organizational structures to improve service delivery and reduce defaults on the loans. Individuals who are part of a group loan program are far more likely to pay their debts and also are less likely to be overwhelmed by them than individuals who take on loans themselves. The program is managed by the Community Organizations Development Institute (CODI), a public organization under the Ministry of Social Development and Human Security. Most construction is done by community members to reduce costs and allow greater control over the quality of the construction. The project reached about 91,000 families and cost the Thai Government about seven million bahts (or about EGP 1.5 million).

The Baan Mankong Program continues to be successful because it has the backing of the central government, which recognizes the value of having communities be the core actors in finding ways to improve their own communities. The Program builds the capacity of local communities to organize and implement projects. It also provides a space in which community members, municipalities, professionals and NGOs can work together to integrate poor communities into the larger city development plans.

This approach improves the long-term sustainability of the project, reduces costs, and ensures that community improvements are community approved. This often leads the community to undertake improvements that are not optimal from a planner’s perspective, but the community still gains valuable implementation experience and overtime will improve their ability to prioritize programs (Boonyabancha 2005, IWPR 2012).

The Bann Mankong Collective Housing Program mechanism. CODI is the fully independent government agency responsible for coordinating the Bann Mankong Program.

Pune, India

The Pune Municipal Corporation implemented an upgrading or in-situ development program that upgraded existing housing stock and improved water and sanitation services for poor families. Families living in homes of poor construction quality were eligible for design and construction services to build a new home on the same site. The national government funded 50 percent of the program, the state contributed 30 percent of the project, and the municipality paid 10 percent of the program costs. The remaining 10 percent of the program costs were paid by residents. Each household paid 30,000 rupees (approximately EGP 3,600) in installments rather than a lump sum to ensure the costs were not an undue burden on their household income. Residents living in sound buildings were given money to improve the water and sanitation connections to their home. The project also served to upgrade public spaces, streets, and green spaces. Prior to receiving services, the community was required to sign an agreement stating that they wanted to have their community upgraded and were willing to work with the project team. The project was managed by NGOs with a longstanding presence in the community (OneWorld Foundation India 2012; Fyhr 2012).

Residents of Pune, India participate in a workshop concerning the upgrading of their community. The full participation of community members is an important component of upgrading projects. © SPARC

Factors of Success

There are several common features of each of these programs that contributed to their success, but three are of key importance. First, the government recognized the assets of communities and the importance of putting residents at the center of the upgrading process. This required citizen participation in every stage of project planning and implementation. Several ministries and government agencies in Egypt, including the MHUUC, GOPP, and ISDF have adopted the language of citizen participation in their programming. However, participation is often limited to community needs assessments and consultation. The latest ISDF upgrading program will be implemented by the army, an institution not renowned for its transparency, openness, or willingness to work with communities (Sayigh 2012).

Second, these governments shunned costly housing programs that provided completed units to residents at heavily subsidized prices and instead searched for low-cost, localized solutions that relied on local knowledge, local materials, and local labor. The Egyptian government needs only to survey the extent of informal areas in the country to recognize the ability and willingness of residents to invest and improve their communities at prices they can afford. Between 1996 and 2006, 78 percent of Cairo’s growth was absorbed by informal areas. Following the 2011 revolution and subsequent break-down in local regulation enforcement, anecdotal evidence suggests that the rate of informal construction has doubled or tripled (Sims 2013). Residents and local contractors are skilled in building communities and have developed their own urban development solutions (Deboulet 2009). A family that manages the construction process themselves can reduce their construction costs by up to thirty percent by employing informal laborers and contractors and shopping for the cheapest materials themselves (Sims 2013). Informal construction of housing is the norm; formal construction is, by far, the exception.

Third, these upgrading programs recognized the importance of an integrated social and physical approach to informal areas. None of the programs concentrated on physical improvements alone. Even the Kampung Improvement Program in Indonesia, which was focused almost exclusively on physical upgrading, recognized the social and economic value of existing settlements. Recognizing this linkage between the built environment and social networks precludes the option of demolishing settlements outright.

Why Does Participation Matter?

Upgrading projects provide ample opportunity for the government to engage with neighborhoods and work with them to prioritize government investments. Participatory upgrading projects can also mobilize citizen volunteers to help implement the work or provide oversight to private contractors. The community played these roles in Mīt `Uqba where residents were able to mobilize local support and government resources to pave their streets and have natural gas infrastructure installed.

Community based upgrading projects can strengthen the relationship between the state and society and help overcome the paternalism of the current planning and urban development paradigm of the government. Residents of Egypt’s informal areas are self-sufficient and innovative. Yet, despite its relative weakness (except in security), the government acts as if they know what is best for the people and assumes a paternalistic role it cannot fulfill. Citizens of informal areas have managed to build robust communities with strong local economies and social networks. More often than not, these communities have had to work around the government rather than with the government, or more appropriately, they have mastered the workings of the informal government. This local knowledge however, comes with costs. Money is wasted in bribing officials and informal power networks in communities are reinforced. Informal construction is not subject to the same oversight and regulation as formal construction which may leave residents at risk if the buildings are poorly constructed. Finally, while the government does not necessarily enforce regulations on new construction, they often prohibit residents from renovating old buildings, especially in historic quarters which leaves the buildings at risk of collapse, endangering residents, and threatening the built cultural heritage of the community.

As the new Egyptian government finds its footing over the next year or two, it is going to face the daunting prospect of managing a difficult macroeconomic situation while satisfying the popular demands of a population with high expectations. If the government persists in implementing large, costly, top-down projects, it will find this task impossible. While keeping an eye on the national development agenda, the government needs to implement projects that are small, inexpensive, and local. While not as flashy as a proposed housing program to build one million homes, participatory urban upgrading projects can help build the capacity and legitimacy of local government, community organization, and build trust between the government and communities at various levels. Egyptians will not only measure urban progress or the strength of their government in the number of homes built, roads paved, or infrastructure networks completed, but in the competence, openness, and the willingness of the government to listen and respond to their needs.

Participation in the design process for upgrading projects can ensure that the projects implemented by the government are what people want at a price they can pay. It also gives the government access to local knowledge. This is not to suggest that there is no place for the technical aspects of project design. Sound technical planning is imperative. However, it is not a substitute for local knowledge and community engagement.

Upgrading existing communities can also have long-term economic implications. Government investment can stimulate a local economy, mobilize local capital, and reshape the local real-estate market to attract higher value uses. However, there is also a risk of displacing low-income residents through gentrification and special care should be taken to ensure that residents have the ability to remain in their homes. It is the responsibility of the government to ensure that the upgrading investments do not negatively impact the standing of the poorest members of the community.

Conclusion

The informal, unplanned, and unsafe areas in cities throughout the country are the result of the systematic denial of the full rights of citizenship for a large percentage of the population. The government’s efforts over the past several decades have been more concerned with limiting the growth of informal areas, mitigating their impact on the shape of the city, or removing them altogether rather than providing public services on par with more affluent, formal areas of the city. The government’s vision of the city unfortunately gives priority to imagined communities that exist only in plans or development schemes to attract investment and ‘beautify’ the city.

This is a failure in both urban planning and governance. Any urban intervention should prioritize the needs of residents living in existing communities. The government should commit to addressing the actual needs of the population (not the government’s perception of what their needs are) in every intervention in informal areas, while minimizing their negative impact. The government should abandon the practice of resettlement in all but the most extreme cases and, in the extraordinary case where resettlement is required, residents should be given a choice as to where they are resettled, and each of the choices should have adequate public services and access to public transportation.

Over the past two generations, the government has failed to adapt their urban policies to the socio-economic dynamics that have resulted in the growth of informal areas. Instead of addressing this shortcoming in their policies, the government has unfairly characterized informal areas as problematic and demonized residents of informal areas to rationalize aggressive, unjust interventions. Will the government continue with the same approach to informal areas or, with the creation of MUDIA, will they adopt a new approach? Will residents in informal areas continue to be alienated and vulnerable or will the government create a space in which residents can participate in the development of their communities, enriching the country in the process?

1.Other entities such as the Ministry of Transportation, Ministry of Finance, the Social Fund for Development, and the General Authority for Cleanliness and Beautification in Cairo and Giza are involved with informal areas, but do not have as direct an impact on them as do the aforementioned authorities. The Ministry of Local Development, responsible for improving the local administration system and implementing government sponsored decentralization efforts, may have a larger impact on the development of informal areas in the long run should local popular councils realize a more significant role in local decision making in the future.2.A feddan is equivalent to 1.0038 acres.

3.We do not use the term in-situ development exclusively as its definition is unclear to most practitioners. Literally, it means development in place. However, it is often confused with rehousing, where residents are temporarily displaced, their homes demolished, and they are rehoused on site.

4.This is not to suggest that there is not any impact on the local economy. Upgrading schemes can have major implications for the real-estate market. Any major investment by the government, improvement of security of tenure, or change in the quality of a community will attract new investment, new residents, and perhaps reshape the nature of a community in the long-term.

5.Kampung is the name used to refer to low-income areas with poor infrastructure provision. It does not necessarily mean slums.

References

Aga Khan Award for Architecture (AKAA). 1980.”Kampung Improvement Programme.” Aga Khan Development Network. Accessed 12 June 2014. Link

Amnesty International. 2011.”‘We Are Not Dirt’ Forced Evictions in Egypt’s Informal Settlements.” London. Accessed 15 June 2014. Link

Baverel, Anne. No Date.”Best Practices in Slum Improvement: The Case of Casablanca.” Development Innovations Group. Accessed 2 July 2014. Link

Boonyabancha, Somsook. 2005. “Baan Makong: Going to Scale with “Slum” and Squatter Upgrading in Thailand.” Environment and Urbanization 17: 21-46.

Choguill, C.L., R. Franceys, and A. Cotton. 1993. “Building Community Infrastructure in the 1990s: Progressive Improvement.” Habitat International 17: 1-12.

Deboulet, Agnès. 2009. “The Dictatorship of the Straight Line and the Myth of Social Disorder: Revisiting Informality in Cairo.” In Cairo Contested: Governance, Urban Space and Global Modernity, ed. Diane Singerman. Cairo: American University of Cairo Press.

Del Mistro, Romano, and David A. Hensher. 2009. “Upgrading Informal Settlements in South Africa: Policy Rhetoric and What Residents Really Value.” Housing Studies 24: 333-54.

Dhakal, Shobhaker. 2002. “Comprehensive Kampung Improvement Program in Surabaya as a Model of Community Participation.” Working paper, Urban Environmental Management Project, Institute for Global Environmental Strategies. Accessed 2 June 2014 Link

El-Batran, Manal, and Christian Arandel. 1998. “A Shelter of Their Own: Informal Settlement Expansion in Greater Cairo and Government Responses.” Environment and Urbanization 10: 217-32.

El-Hefnawi, Ayman Ibrahim Kamel. No Date. “”Protecting” Agricultural Land from Urbanization or “Managing” between Informal Urban Growth While Meeting the Demands of Communities (Lessons Learned from the Egypt Policy Reforms).” Ministry of Housing Utilities and Urban Communities, Egypt. Accessed 2 July 2014. Link

El-Shahat, Manal M. F. , and Samah M. El Khateeb. 2013. “Empowering People in Egyptian Informal Areas by Planning: Towards an Intelligent Model of Participatory Planning.” Paper presented at: Cities to be Tamed? Standards and Alternatives in the Transformation of the Urban South, Milan, Italy. Planum: The Journal of Urbanism 1: 26.

Farid, Doaa. 2014. “Armed Forces to Implement an Egp 350m Project for Developing 30 Slum Areas.” Daily News Egypt, 5 January 2014. Accessed 6 June 2014. Link

Fernandes, Edesio. 2010. “The City Statute and the Legal-Urban Order.” In The City Statue of Brazil: A Commentary: Cities Alliance, Nacional Secretariat for Urban Programmes, and Brazil Ministry of Cities. Accessed on April 2, 2013. Link

Fyhr, Kyle. 2012, “Participation in Upgrading of Informal Settlements: A Case Study of the Project ‘City in-Situ Rehabilitation Scheme for Urban Poor Staying in Slums in City of Pune under Bsup, Jnnurm.” Stockholm University. Accessed 7 August 2014. Link

Giridharadas, Anand. 2006. “Not Everyone as Grateful as Investors Build Free Apartments in Mumbai Slums.” New York Times, 15 December 2006. Accessed 2 July 2014. Link

Government of Egypt (GoE). 2014a. ”Unofficial Translation of the 2014 Egyptian Constitution.” Accessed 3 August 2014. Link

———. 2014b.Presidential Decree No. 1252/2014.

———. 2009. “Executive Regulations Implementing Law on Building No. 119 of the Year 2008.” In Law 119/2008. The Middle East Library for Economic Services.

———. 2008a. Law on Building No. 119/2008.

———. 2008b. Presidential Decree No. 305/2008.

India, OneWorld Foundation. 2012. “In-Situ Slum Upgradation under JNNURM” Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions, Government of India. Accessed 7 August 2014. Link

Informal Settlements Development Facility (ISDF). 2013. “Development of Slum Areas in Egypt.” ed. Informal Settlements Development Facility.

———. 2011. “تقرير لجنة تقدير الاحتياجات الخدمية لتوطين سكان المناطق المهددة للحياة بمدينة 6 أكتوبر.”

Informal Waste Pickers and Recyclers (IWPR). 2012. “The Project Baan Makong and the ‘Community Organizations Development Institute’ (CODI) of Thailand.” Informal Waste Pickers and Recyclers. Accessed August 8 2014. Link

Khosra, Renu. 2009. “Economics of Resettling Low-Income Settlements (Slums) in Urban Areas: A Case for on-Site Upgrading.” Urban India 29: 22-49.

Magalhães, Fernanda, and Francesco di Villarosa. 2012. “Slum Upgrading: Lessons Learned from Brazil.” In Secondary Slum Upgrading: Lessons Learned from Brazil. Intern-American Development Bank. Washington, DC. Accessed 30 June 2014. Link

Mitchell, Timothy. 1991. “America’s Egypt.” Middle East Report 21. Accessed 14 August 2014. Link

Miranda, Juan. 2014. “Forward.” In Lose to Gain: Is Involuntary Resettlement a Development Opportunity? , ed. Jayantha Perera. Philippines: Asian Development Bank. Accessed 7 August 2014. Link

Nada, Mohamed. 2011. “The Politics and Governance of Implementing Urban Expansion Policies in Egyptian Cities.” Égypte/Monde arabe Third Series, 11. Accessed 18 June 2014. Link

Patel, Sheela. 2013. “Upgrade, Rehouse or Resettle? An Assessment of the Indian Government’s Basic Services for the Urban Poor (BSUP) Programme.” Environment and Urbanization 25: 177-88.

Institute of National Planning (INP). 2000. “Egypt: Human Development Report 1998/99.” In Secondary Egypt: Human Development Report 1998/99. Kalyoub, Egypt: Al-Ahram Commercial Press. Accessed 30 June 2014. Link

Salama, Amr Ezzat. 2006. “Egyptian Codes for Design Construction of Buildings.” In Building the Future in the Euro-Mediterranean Area: Workshop. Varese, Italy. PowerPoint Presentation. Accessed 7 August 2014. Link

Sayigh, Yezid 2012. “Above the State: The Officer’s Republic in Egypt.” Carnegie Middle East Center, Beirut, Lebanon. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Accessed 7 August 2014. Link

Séjourné, Marion. 2009. “The History of Informal Settlements.” In Cairo’s Informal Areas: Between Urban Challenges and Hidden Potentials, eds. Regina Kipper and Marion Fischer: Cairo: GTZ Egypt and Participatory Development Programme in Urban Development (PDP). Accessed 7 August 2014. Link

Sims, David. 2013. “The Arab Housing Paradox.” The Cairo Review of Global Affairs. 24 November 2013. Accessed 7 August 2014. Link

———.2012. Understanding Cairo: The Logic of a City Out of Control. Cairo, Egypt: American University of Cairo Press.

USAID. 2010. “USAID Country Profile, Property Rights and Resource Governance: Egypt.” United States Agency for International Development. Washington, DC. Accessed 2 July 2014. Link

Victora, Cesar G., Linda Adair, Caroline Fall, Pedro C. Hallal, Reynaldo Martorell, Linda Richter, and Harshpal Singh Sachdev. 2008. “Maternal and Child Undernutrition: Consequences for Adult Health and Human Capital.” The Lancet 371: 340-57.

Comments