Adequate Housing Approach as a Targeting Tool for Local Development

Driving through Cairo’s neighborhoods, one can clearly see the stark differences in the quality of life and public investment across different – and often adjacent – neighborhoods. Why do some areas continue to be well maintained, while a neighboring one is overflowing with uncollected garbage and streets with potholes? Who decides the value and quality of public resources a specific area receives to serve its residents, and on what basis?

Within the Egyptian context, identification of local needs, hence the allocation of public resources remains unclear. The absence of clearly-announced criteria – based on local needs – to allocate public resources across neighborhoods and districts created multiple forms of spatial deprivation.

The government launched several programs to relieve the deprivation in rural areas through geographic targeting programs, the most recent being the Development Program for the Poorest 1000 Villages. Previous programs that aimed to reduce the urban-rural gap include the Shorouk Program, the Fast Track Plan Program, and others. These geographic targeting programs have not been enough to eliminate rural poverty in Egypt. Studies raised some concerns about the indicators used for the selection of these villages and the amount of funds available to even upgrade the chosen villages (Abdelhaliem, 2012). In fact, multiple empirical studies lean towards that geographic targeting has never been enough to replace a just allocation for public resources through robust and sustainable mechanisms (Elbers et al., 2004; Baker and Grosh, 1994; Baliscan, 2007).

In the urban areas, spatial focus was more based on “planning” criteria, rather than “poverty” or “deprivation” indicators. Some neighborhoods were classified as “unsafe” based on the location and structure of the building, “unplanned” based on whether it was planned by official planning mechanisms or not.

Studies and statistics often focused on development indicators on the national level, such as the poverty indicators and Gini coefficient.1 Relying on these figures to evaluate the well-being of citizens often shows an incomplete picture, since it fails to take into account the quality of other resources such as housing, services, and job opportunities – all of which have direct impacts on a citizen’s quality of life. Except for few studies, tackling spatial dimensions of inequality or injustice focused on the rural-urban gap. A comprehensive definition of spatial deprivation was hardly used.

As such, as part of TADAMUN’s Planning [in] Justice project, this brief aims to shed light on these development gaps by taking a closer look at how public resources are distributed within the same city, and suggests adopting the concept of “adequate housing” as a more comprehensive indicator for prioritizing the allocation of development projects.

As discussed in an earlier TADAMUN article, it is imperative to note the difference between the equitable and just distribution of resources. An equal distribution ensures that everyone receives the same amount regardless of any discrimination or privileges, while distributing justly acknowledges that some disadvantaged groups need more support to be on an equal footing with others, and hence should receive more. Applying this concept to the distribution of public resources within the city entails the allocation of public funds based on equal per-capita distribution among neighborhoods (equal distribution), compared to distribution based on the severity of the local needs (just distribution). The latter understanding allows us to examine residents overall quality of life through the public resources and services allocated to them, their quality of housing and jobs, etc. Unfortunately, as we will see in this brief, the distribution of public resources in Cairo is neither equal nor just. This is not to say that the government doesn’t allocate millions of pounds to development projects throughout the city, but how these projects are selected and spatially allocated, and whether they correspond to local needs are the questions at hand.

Fiscal Planning: Needs Assessment and Drafting the National Budget

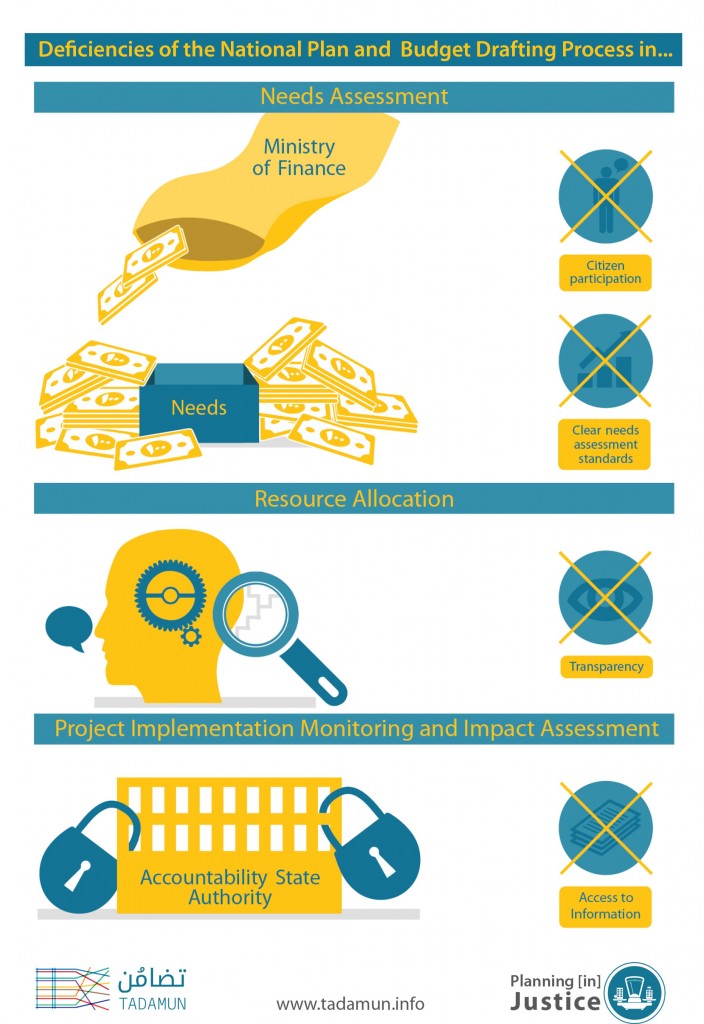

In order to ensure a spatially just allocation of public resources, several institutional conditions need to be present:

- Clear, publicized resource allocation standards that correspond to local development needs;

- Correlation between distributed funds and achieving clear economic and social development goals on the local level, in order to fulfill the social contract between the people and their government;

- An active public role in needs assessment and setting development priorities, which requires effective communication channels with local executive authorities;

- Transparency and accountability tools of public spending and the implementation of public projects, not only fiscal accountability but also measuring the impact of these projects on the overall wellbeing of residents.

Examining the needs assessment and resource allocation processes in Egypt from a fiscal point of view will illustrate the absence – or at best, the weak presence – of most of the above factors.

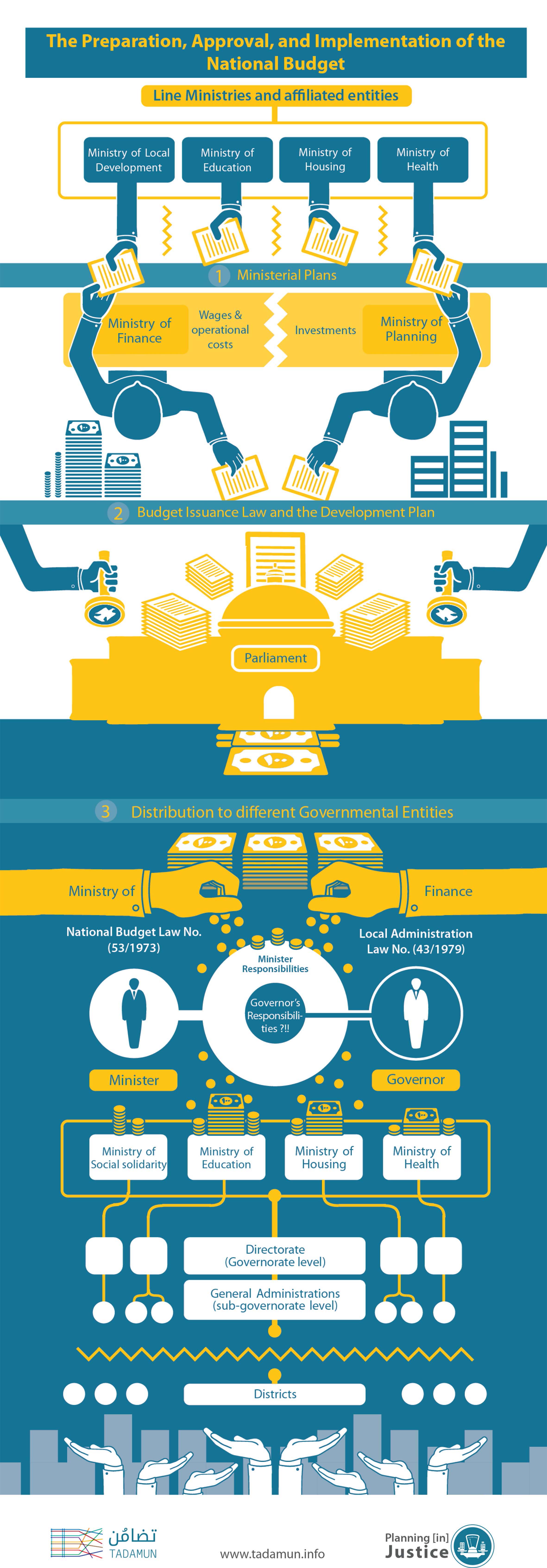

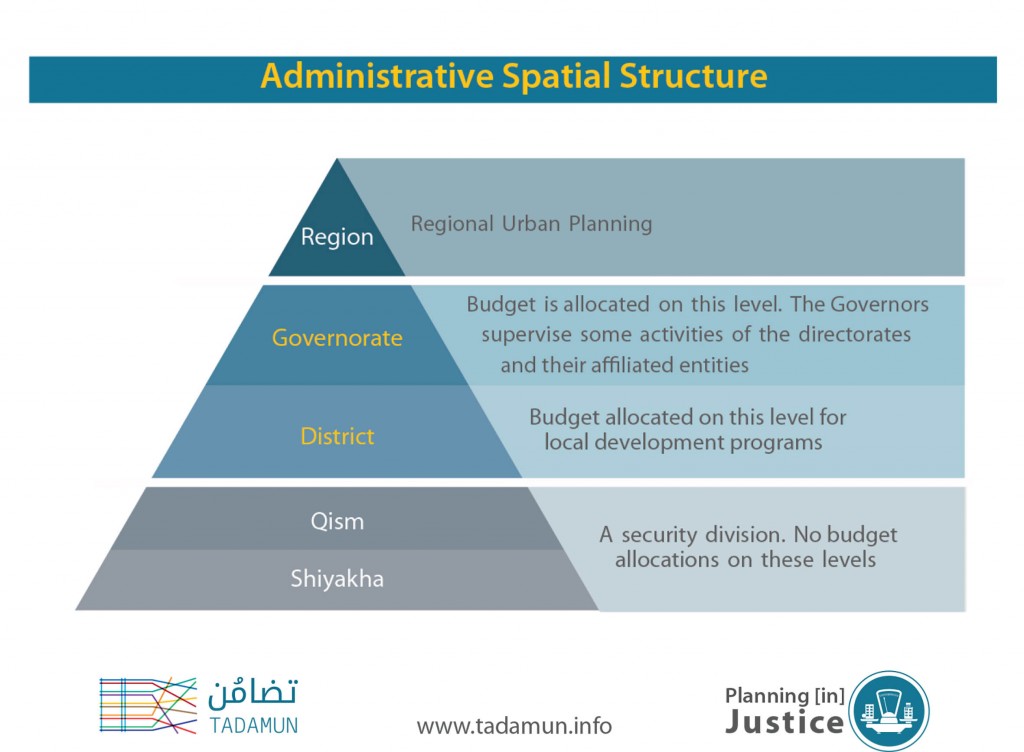

As a highly centralized state, the majority of the local public resources are allocated at the central level through the Ministry of Finance (MoF). The process of setting the national budget and development plan is regulated by Law No. (53/1973) which does not include any requirements for setting development goals or clear development benchmarks as part of the process. The MoF releases a charter for the preparation of the budget, then gathers the proposed budget by all public entities starting from the lowest administrative level, and subsequently forms a committee that includes representatives of the MoF, Ministry of Planning (MoP), the Central Agency for Organization and Administration, the National Investment Bank, and representatives of different executive agencies. This committee is responsible for evaluating different government agencies draft budgets. Execution of the budget starts by allocating money for different entities and projects by Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Planning; which might differ from the initial needs proposed to the Ministry of Finance before.

The national budget process does not have any mechanisms that link fiscal planning and well-defined local development needs. It is classified to expenditure items that are only audited financially through the Accountability State Authority, with no regard to the socioeconomic impact of public spending. By contrast, a programs-based budget, which would tie funding to specific development goals in the form of programs, such as basic health care and education, is not used in Egypt. This is despite the fact that the charter for the preparation of the budget in 2015/2016 stated that the government would start implementing the program-based budget in some sectors. This pledge is repeated in the 2016/2017 charter.

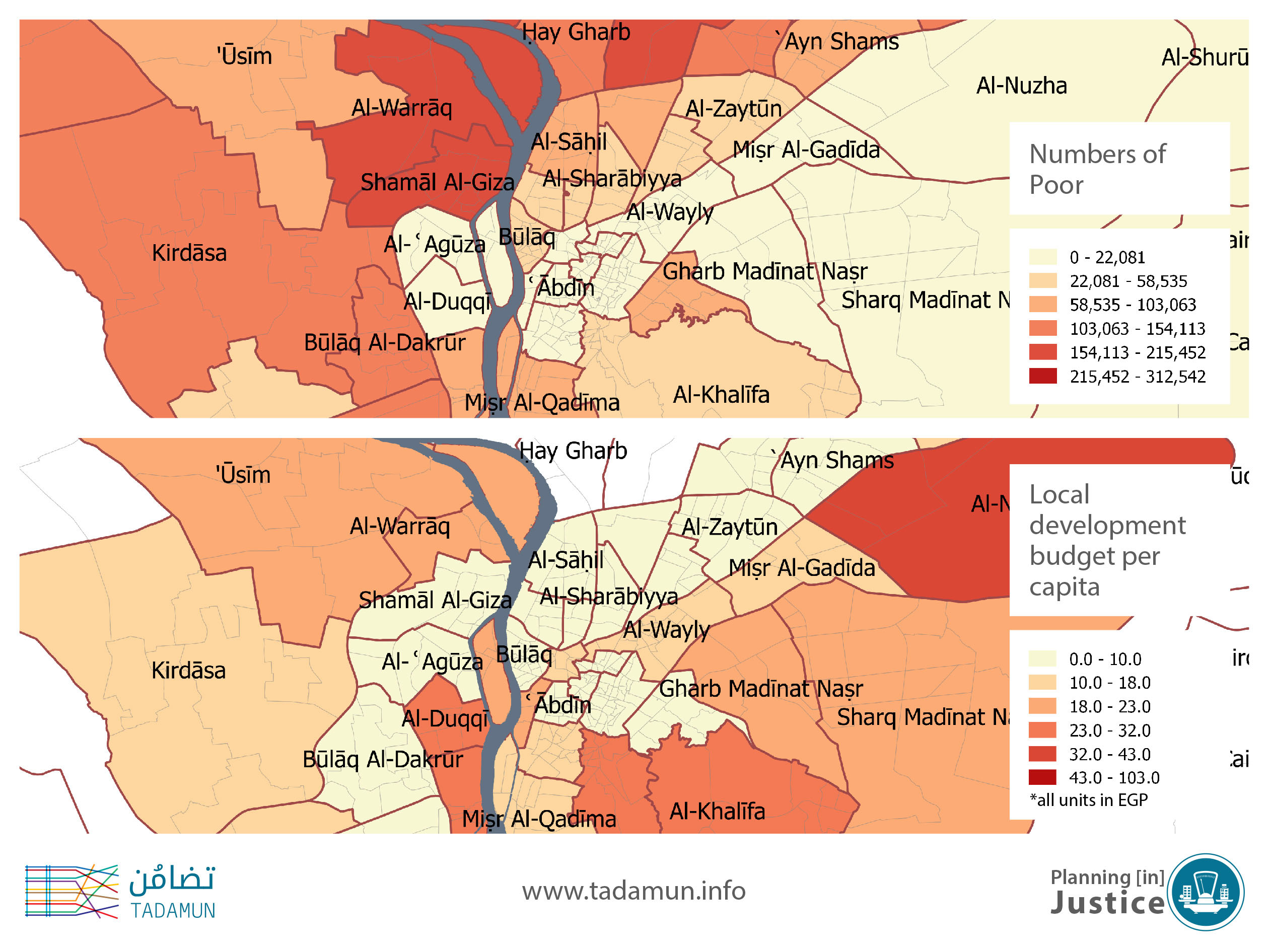

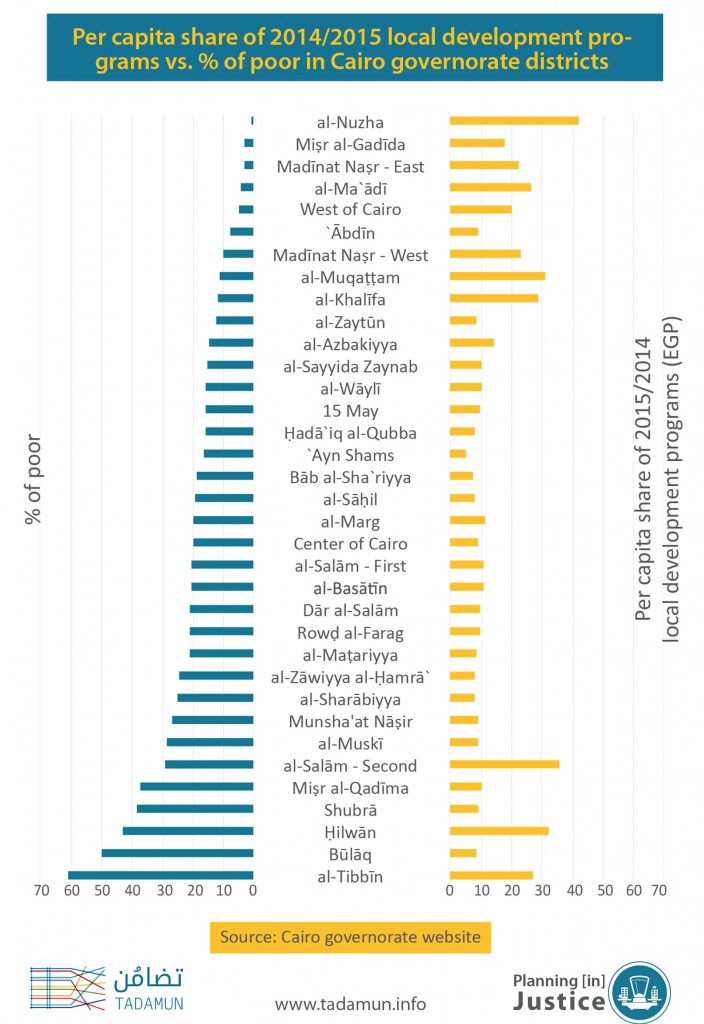

Public investments tend to concentrate in some areas over others, this occurs even in the allocation of budgets in sectors that are known to rely on funding formulas like the local development programs’ budget, where the formula itself neglects the degree of spatial deprivation. The below map contrasts the number of poor residents (top map) with per-capita local development budget (bottom map). The map clearly shows that al-Nuzha district residents (one of the most affluent districts in North-East Cairo) receive the highest per-capita allocation, while areas with higher a number of financially-struggling population (such as Ain Shams and Misr al-Qadima) receive much lower per-capita allocations. There are no mechanisms or tools that ensure a just geographic distribution of public funds across the country, or even within the same city, so that the basic needs of all citizens are met.

Additionally, Article 26 of the Local Administration Law No. (43/1979) gives governors full authority over executive issues in their governorate. However, it does not rectify overlapping and multiple kinds of fiscal planning by various line ministries. This leaves governors burdened by administrative duties and public expectations for addressing problems in their governorate but they do not have control of their budget. A clear result of this dual responsibility is the recent flooding disaster in Alexandria, which resulted in the death of seven people. The public blamed the Governor, while he pointed the fingers at the general administrations (which are under the jurisdiction of their corresponding ministries) for not allocating the needed funds to properly maintain the city’s ageing sewage system.

Public participation

There are two avenues for the public to contribute to the country’s budget process, the first is through their elected representatives at the Local Popular Councils (LPC) (inactive since 2011) who review and pass the budget of agencies operating at the local level only, particularly the local development programs budget. The second is through the elected Parliament (dismantled 2013-2015), which gives its final approval of the drafted national budget. Feed-back channels between the central determined budget and local needed budget remain blocked, due to the lack of fiscal decentralization and due to the fact that LPCs’ opinion do not have a real impact on the final centrally-set budget.

The LPCs are the main connection between the citizen, his/her geographic location, and the national budget, and even if they truly represent and voice local needs, they are hindered by legislation – in particular the Local Administration Law No. (43/1979) – that gives ministries the final say in evaluating needs and setting the corresponding budgets at the district level. After gaining the approval of the LPC, the proposed budget is presented to the Governor, followed by the High Committee for Regional Planning. The Minister of Planning in coordination with the Minister of Local Administration then coordinate between the submitted plans and the national general plan. This is all juxtaposed with the national budget Law No. (53/1973) which gives the MoF full authority in setting the national budget without having to comply with the proposals made by the other ministries or the LPCs. To put it simply, LPCs have the legal right to discuss the local budget and make recommendations, however their recommendations are not legally binding to the MoF, which has the final say.

Transparency and Impact assessment

Financial resources and the national development plan are allocated by central government agencies, as discussed above, and are then made available to the public on the MoF’s website.2 However, the distribution of the national budget on the local level is withheld, with public access limited to the Directorate level in the governorate. This prevents citizens from knowing the magnitude of public resources invested their district receives for public services and development projects, and from holding their officials accountable for these funds. Similarly, the State Investment Plan – prepared by the MoP – publishes the name of planned projects on the district level but without the accompanying budget figures.

Only one portion of the Economic and Social Plan, the local development projects, can be seen at the local district level, and they constitute less than 1% of public expenditures. These projects are limited to road paving, lighting, safety, street lighting, environment improvement, and local administration support.

There is no legislation that ensures the details of these projects are publicly available, and as such, one finds large discrepancies between the availability and level of detail offered by various districts and governorates. At most, the development projects are shown at the district level, not the shiyakha level (the smallest local administration unit), and at worst, the information is not published at all.

In addition, none of the above public records provide information on public spending on the shiyakha level, which is where citizens feels the direct impact of public spending and upgrading efforts – or lack there of. The national budget doesn’t actually delineate how local development funds should be spent below the district level, giving district heads free authority to distribute resources among its shiyakhas as they see fit, with no mechanism of internal or public oversight.

Despite the limited information on the shiyakha level, we can compare the distribution of public schools within a district – on the shiyakha level. If we take the district of Sharq Madinat Nasr, a high-mid income district in the north-east of Cairo, and one of its shiyakhas, Izbit al-Haggana (one of the largest informal settlements in Cairo), we find that out of the 22 public schools in the district, only three are located in and serve Izbit al-Haggana’s very large student population.3 Additionally, interviews with school staff in the area revealed delays in the distribution of yearly bonuses, compared to school staff in the rest of the district. These disparities could be examined in other services if data on public resource distribution was made available at the shiyakha level.

People have a constitutional right to access information (Article 68, 2014), although this constitutional provision has yet to be activated legislatively. How can the public hold the executive branch accountable if they are unaware of where and how public investments are made in their neighborhoods? It is even more problematic that none of the state monitoring agencies look at the impact, output, or even the implementation of the numerous local investment projects across the country.

Urban Planning: Urban Classifications as Targeting Tools

Parallel to the fiscal planning system described above that funds the local administration structure and public services such as health and education and local development projects on the district level, there are urban planning agencies affiliated with the Ministry of Housing that prepare strategic urban plans for the development of urban areas across the country. The work of these urban planning agencies is highly influenced by the national strategies such as redirecting urban expansion into the desert, and “eliminating slums”.

Urban planning in Egypt is primarily based on the classification of the built environment, which then dictates the urban policy adopted to deal with the area. Urban areas are broadly classified in the Egyptian legislation as: planned, unplanned, and unsafe.4 Interestingly, despite its popular use by government officials and the general public, the term Ashwa’iyyaat (informal) is not properly defined in any Egyptian legislation – Its only mention is in the 2014 Constitution (Article 78). Over the past two decades, the government started targeting some urban pockets for upgrading based on the above classifications; ‘unsafe’ and ‘informal’ areas were identified by the Informal Settlement Development Facility (ISDF), which is currently under the Ministry of Housing.

There are several problems with using the simple dichotomy of planned/unplanned as tools to target development efforts and urban policy. First, the above classifications reflect the legality of the built environment and its compliance to building codes and planning standards, but don’t capture localized development needs and opportunities and mask the variation within areas categorized as ‘informal’. This label doesn’t say much about the problems in these areas, whether it is absence of public services, high poverty levels or deteriorated housing stock and infrastructure, or other public services. Coupled with the lack of meaningful public participation in most upgrading projects, development efforts often end up not always tackling the most important local problems. On the other hand, the ‘unsafe’ category is more representative of the nature of the area, as the ISDF’s four-tier definition break down the unsafe parameter in a way that reflects some of the area’s needs.

Secondly, these classifications tend to be a life-long label attached to these areas regardless of government-, NGOs-, or foreign donors- launched development projects, which cost millions of pounds. The authorities responsible for creating these databases don’t consider the dynamic evolution of neighborhoods. These static labels may attract some overdue improvements in some areas labeled “informal” but other areas that are not classified as informal may even be in more dire straits, yet fail to attract the attention of decision-makers and/or the media.

Third, there is no national or even citywide agreed upon figures or demarcations of these urban classifications, as there are no clear, agreed-upon definitions of “informal” and “unplanned” areas. The ISDF has defined ‘unsafe areas’ and used this four-tiered classification system to move people out of particular areas and suggest other government efforts to improve these areas.5 Unfortunately, too many government agencies try to define these labels but they do not always agree with each other. For example, in 2008 the Ministry of Local Development, along with the General Organization for Physical Planning and UN-Habitat collaborated on creating a definition of ‘informal’ areas, while the Shura Council (High House of Representatives) also created its own definition of the term. Neither of which were nationally adopted or recognized by the Ministry of Housing.6

Finally, speaking of institutional issues, the decision-making process of classifying an urban area, which contributes to the allocation of development funds, lacks the public’s voice. The public has no say in the process of classifying an area or setting its development priorities. For instance, interested groups don’t have a mechanism through which they can demand the inclusion of an area within an upgrading project tackling informal or historic areas in their governorate.

In other words, current urban classifications often limit the comprehensive understanding of our cities in a balanced and dynamic way that focuses on how to redistribute and target public resources across the city to eliminate, or at lessen, existing gaps in the quantity, quality and access to public services and facilities between different areas.

Deficiencies in Current Development Planning

As this brief illustrated so far, there are several deficiencies in the ability of current fiscal and urban planning and spatial targeting programs mechanisms in prioritizing target development areas in a way that truly reflects the local needs and challenges. These shortcomings are not only reflected in government development projects, but is also reflected in internationally-funded projects, which select intervention areas based on government recommendations. Yet, these recommendations are based on static labeling, instead of prioritizing interventions based on a dynamic evaluation of local needs.

The Awla bi-l-Ri`āya (most care-worthy) housing in 6th of October City, commonly known as ‘Masākin `Uthmān’, is an example of a community that has fell through the cracks of the urban classification system. Masākin `Uthmān is a public housing area that currently mainly houses residents of informal areas that were evicted due to the unsafe nature of their dwellings, in addition to Arab and African immigrant populations. Despite being a ‘planned’ area by the ISDF standards, the area is deprived of almost all public services, with no nearby security presence, schools, health units, or food outlets, water cuts last weeks at a time, etc. Residents are left to live in a very hostile physical and social environment. The area and its residents face problems that are comparable, if not at times worse, that most in Cairo’s informal areas but they don’t receive the attention of any government agency, and neither is it on the list of any future development plans.

“Adequate Housing” Concept as Indicator for Targeting for Development

As such, there is a need for an integrated local development approach that looks at different areas and their needs, rather than the ad-hoc approach currently adopted by the government. Decision-makers should move past the focusing on classifying a community as planned/unplanned, safe/unsafe to a more comprehensive understanding of development needs. TADAMUN proposes using the criteria of “adequate housing” as a suitable indicators to better target problem areas and improve public service delivery and allocation.

In 1966, the United Nations released the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights recognized adequate housing as a human right (Article 11), but it wasn’t until 1991 that a clearer definition of “adequate housing” adopted, which qualifies the definition through the following seven criteria (United Nations, 1991):

Legal security of tenure: A secure tenure protects persons against forced eviction, harassment, and other threats. It can take a variety of forms, including rental (public and private) accommodation, cooperative housing, lease, owner-occupation, emergency housing, and informal settlements (including occupation of land or property).

Availability of services, facilities, and infrastructure: An adequate house must contain certain facilities essential for health, security, comfort, and nutrition, such as safe drinking water, energy for cooking, heating and lighting, sanitation, waste disposal, etc.

Affordability: Personal or household financial costs associated with housing should be at such a level that the attainment and satisfaction of other basic needs are not threatened or compromised.

Habitability: Adequate housing must be livable and provide adequate space for its inhabitants. It should also be structurally intact and provide protection from cold, dampness, heat, rain, wind or other threats to health.

Accessibility: Disadvantaged and marginalized groups must be accorded full access to adequate housing resources. This includes groups such as the elderly, children, the physically and mentally challenged, the terminally ill, victims of natural disasters, and people living in disaster-prone areas.

Location: Adequate housing must be in a location that allows access to employment options, health-care services, schools, child-care centers, and other social facilities. Similarly, housing should not be built on polluted sites or near pollution sources that can threaten the health of the inhabitants.

Cultural adequacy: The way housing is constructed, the building materials used and the policies in place must appropriately enable the expression of cultural identity and diversity of housing.

Other cities have implemented similar approaches in targeting development efforts. Successive Mayors of Bogota (Columbia) implemented innovative policies to reduce inequality in the city through projects that target increasing the accessing public services, security, and promoting civic participation (UCLG, 2012).

Much of the information needed to utilize these criteria to target development is already collected through the national census, and can be utilized to create a more comprehensive matrix of adequacy of housing across the city. For instance, an indicator can be developed for the ‘availability of services’ criteria through the national census data on the number of public schools, hospitals, youth clubs, police stations, post offices and many other services documented on the shiyakha level.

However, one must note the limitations to this sampling methodology of using available data from the national census, which is conducted every 10 years in Egypt. First, not all information is made available on the smallest administrative level; the most common level of details publicly available is at the district level. Second, the long period between the census data collections may not reflect changes in the areas, particularly as one draws closer to the 10-year mark (UCLG, 2012). Third, the data needed to comprehensively develop a adequate housing parameter may not be part of a data set collected by the government. For instance, if we look again at the ‘availability of services’ criteria, it would be important to know the length and mode of residents’ commute to work, school, and other basic public services. Unfortunately this data is not collected by any government agency in Egypt.

Conclusion

Putting the provision of adequate housing as one of the national goals – as outlined in the Egyptian Constitution – when resources are allocated on the city, region, and governorate levels, allows one to have a clearer look at the conditions on the ground and for decision-makers to make informed decisions as to where funding should be allocated and for which projects, in order to better tackle these inequalities. For this to be successful, this needs to be accompanied by a strong local administration that is empowered financially and administratively by legislation, and is strongly rooted by its constituency’s voice and real partnerships with civil society.

1.The Gini coefficient is one of the most commonly used indicators to measure inequality by measuring the distribution of income among the population. The values range between 0 and 1 (can also be represented as a 0-100%), with a 0 value meaning equal distribution of income, and a value of 1 meaning that all of the income generated is held by 1 person.

2.The MoF’s Arabic website is updated with the 2015-2016 national budget.

3.These figures were extracted from data published by the Ministry of Education.

4.The unplanned category is defined according to the Unified Building Law No. (199/2008), while the planned areas and four-tier classification of unsafe areas are defined by the ISDF.

5.The ISDF’s four-tier definition of “unsafe” areas is currently the clearest definition of urban classifications, and the ISDF produced a map with the locations of said areas.

6.An elected entity that is no longer part of the political system in Egypt.

References

Abdelhalim, Reem. 2012. “Institutional Factors of Sustainable Poverty Eradication: Special Analysis to Land Governance in the Case of Egypt.” In Annual World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Baker, Judy L., and Margaret E. Grosh. 1994. “Poverty Reduction through Geographic Targeting: How Well Does It Work?” World Development 22 (7): 983–95. doi:10.1016/0305-750x(94)90143-0.

Balisacan, Arsenio M., and Ernesto M. Pernia. 2002. “The Rural Road to Poverty Reduction: Some Lessons from the Philippine Experience.” Journal of Asian and African Studies 37 (2): 147–67. doi:10.1177/002190960203700207.

Elbers, Chris, Tomoki Fujii, Peter Lanjouw, Berk Özler, and Wesley Yin. 2004. “Poverty Alleviation Through Geographic Targeting: How Much Does Disaggregation Help?” Journal of Development Economics 83 (1): 198-213.

United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG). 2012. “Who Can Address Urban Inequality? The Often Forgotten Roles of Local Government.” Addressing Urban Inequalities: The Heart of the Post‐2015 Development Agenda and the Future We Want for All, Global Thematic Consultation. https://bit.ly/2Q1pOMn

United Nations. 1991. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. General Comment 4, The Right to Adequate Housing. E/1992/23, 13 December, 1991.

Comments