Urban Mobility: More than Just Building Roads

Urban Mobility in Cairo: Governance and Planning

With an estimated traffic volume of 7,000 vehicles per hour per lane on major corridors such as the 6th of October bridge and the Ring Road at Carrefour al-Ma`ādī during peak hours (World Bank, 2014), Cairo has become notorious for its chronic traffic congestion. With the Greater Cairo Region (GCR) home to more than 19 million inhabitants with this number expected to grow to 24 million by 2027 (ibid), the demand for transportation options will only increase and put additional strain on already “overcrowded” transportation infrastructure. The standard response in Egypt and in many other countries to mobility challenges has been to increase transportation infrastructure in the form of more roads, bridges, tunnels or flyovers. This has often led to environmental degradation, with transport responsible for 23% of total energy related greenhouse gas emissions in 2010, and more congestion. This vehicle-focused infrastructure upgrading mainly benefits a certain section of society, excluding the majority of the population who depend on public transportation.As cities continue to grow, planners are facing the challenge of designing urban mobility systems that are sustainable on social, economic, institutional and ecological levels. To achieve this, there are growing calls from planners for a paradigm shift in transportation planning: to move away from the transport bias, which equates mobility to transportation, and to put more focus on people’s accessibility needs. This growing trend views accessibility as an enabler for economic activity and social connectivity which can be used to unlock communities’ development potentials. In this article, we will shed light on this paradigm shift and the ways in which redefining mobility problems can lead to different solutions which promote sustainable development efforts. We will also introduce the most critical issue facing the mobility sector in the GCR.

Towards Sustainable Mobility Concepts

The old transport planning paradigm was focused on maximizing the distances people travelled given specific time and money constraints. The objective, therefore, was to increase traffic flow capacity. The system’s efficiency was evaluated based on the speed, affordability and convenience of motorized transport. Mobility problems were viewed in isolation by different agencies operating separately which led to disintegrated solutions where solving one problem often exacerbated another. An example of that is when a transport agency expands roads, it induces vehicle travel which exacerbates fuel consumption and it associated environmental consequences.

Currently, transportation planning is undergoing a paradigm shift. The new model of transportation planning recognizes that mobility is not a goal in itself. UN-Habitat declares that the ultimate purpose “is to create universal access to safe, clean and affordable transport for all that in turn may provide access to opportunities, services, goods and amenities.” Sustainable urban mobility, thus, evaluated and determined by the accessibility of the city to its residents without discrimination based on age, gender, physical ability or economic levels.

This shifts the focus to people with the primary objectives of enhancing accessibility and quality of life, promoting environmental and financial sustainability, as well as social equity. It encourages planners to overcome the political, economic, social and physical constraints to movement.

Urban Mobility as a Human Right and an Enabler of Sustainable Development

In moving towards using accessibility rather than physical travel to define and measure mobility we acknowledge the central role of well-developed transport systems in achieving development goals. This was recognized in the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in target 11.2 whose aim is to “provide access to safe, affordable, accessible and sustainable transport systems for all, improving road safety, notably by expanding public transport, with special attention to the needs of those in vulnerable situations, women, children, persons with disabilities and older persons” by 2030.

Not only does this target contribute to the SDG Goal 11 “making cities and human settlements, inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable”, it is relevant to the majority of the goals. For example Goal 3 is concerned with ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all, at all ages. In Uganda systematic reviews of evidence indicated that as much as 80% reduction in maternal mortality was possible due to medical referral and transportation strategies alongside other interventions. Similarly, by guaranteeing the acceptability of different modes of transportation by, for instance, ensuring the safety of women and girls on them, planners will be contributing to Goal 5 concerned with achieving gender equality and empowering women and girls who may otherwise be deterred from using them.

The Council of European Municipalities and Regions even considers sustainable urban mobility as a human right, declaring that “the right to mobility is universal to all human beings, and is essential for the effective practical realization of most other basic human rights.” By elevating the status of urban mobility to a human right, the council puts it beyond just functionality and economic justification and places it on the same level of other issues central to fulfilling human rights.

Urban Mobility in the Greater Cairo Region

The Egyptian constitution recognizes the freedom of movement as a right in Article 42; however, it neither discusses urban mobility nor public transportation. Despite the meshing of the different forms of formal and informal public transportation modes in the GCR, the private and public transportation systems display significant inefficiencies which are reflected in inadequate services with deteriorating quality, especially for the urban poor, who often have to rely on low quality and unsafe forms of travel. One of the major issues facing the GCR is an extremely high road accident rate which surpasses comparable megacities. According to the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS), there have been 15,516 road accidents in Egypt in 2012 alone, amounting to 21,620 Road Traffic Injuries (RTI) and 6,431 Road Traffic Fatalities (RTF) (CAPMAS, 2012). This translates into a national average of 1.8 accidents/hour and 1.5 injuries and fatalities/hour in Cairo alone. These figures are continually increasing with 9086 deaths reported in 2013 due to transport accidents, with projections indicating that RTFs are expected to reach 20,000 by 2020 (WHO, 2009). Experts have estimated the cost of an average Egyptian life to the society and economy to range between EGP 1 and 3 million (WHO, 2009). Combining both, a conservative estimate would be over EGP 6 billion lost to RTF on a yearly basis. Looking specifically at pedestrians, the percentage of pedestrians and cyclists in RTIFs range from 20% to 75% of RTIs in Egypt (Ibrahim et al, 2012).

Other critical issues facing the capital as detailed in a report by the World Bank (2006) are most notably the chronic traffic congestion, which planners mostly respond to by constructing more roads, which as discussed earlier further exacerbates the problem. More than being a nuisance, congestion in GCR has high economic and environmental costs due to time and fuel wastage as well as increased emissions. An often cited statistic is that EGP 47 bn or 3.6% of Egypt’s total GDP is lost due to congestion, 19% of which are represented by the health impacts associated with transport-related air pollution (World Bank, 2014). Air pollution in the GCR, a serious environmental and public health concern, is largely caused by mobile sources of air pollution, which include vehicles, and agricultural or construction equipment. Despite successful government efforts to reduce air pollution, in 2009 concentration levels of the PM10 pollutant in the GCR, which contributes to the risk of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, were twice the Egyptian standards and approximately seven times more than the WHO standards. Other pollutants such as nitrogen oxides were also found to be above WHO levels.

On the governance level, the responsibility of the transportation sector is fragmented between multiple authorities, which are largely uncoordinated, and often inadequately equipped to deal with Cairo’s complex urban mobility issues. These problems are further magnified by inadequate financial resources which often lead to under investments specifically in the public transport system. On the national level this translates into almost non-existent public transportation systems particularly, in rural areas and smaller cities, with only two public transit authorities in all of Egypt, operating in Alexandria and Cairo.

The Right to Adequate Urban Mobility

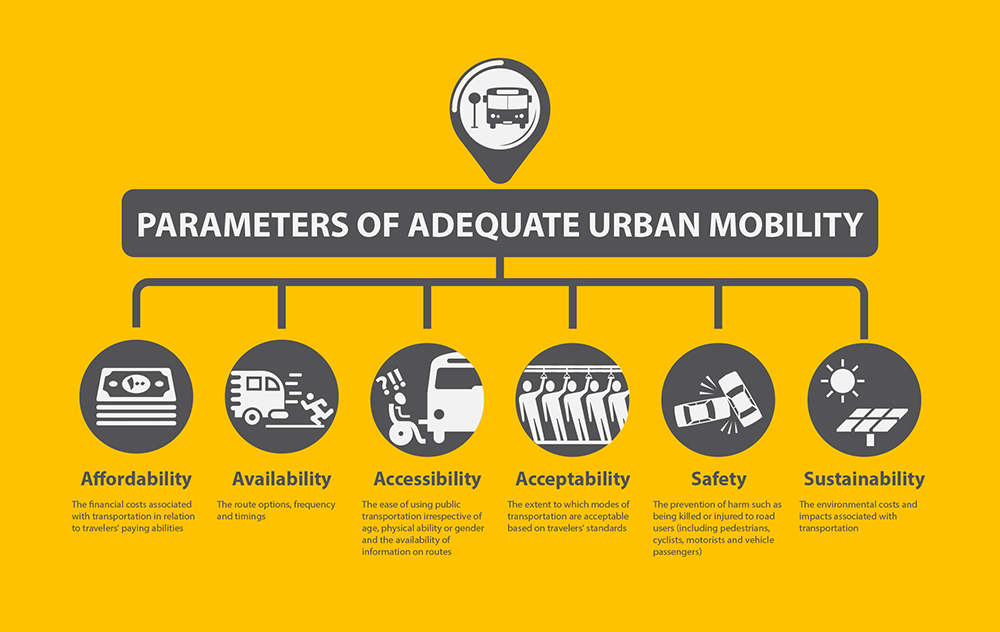

To overcome the political, economic, social and physical constraints to movement in the GCR and establish it as a right for the inhabitants of the city, it is important to identify the factors, which contribute to adequate urban mobility. Based on the definitions of sustainable urban mobility put forward by the UN-Habitat and the SDGs, we have, therefore, developed the following parameters of adequate urban mobility: affordability, availability (denotes route possibilities and frequency), accessibility (encompasses the ease of using public transport by users irrespective of their age, gender and physical abilities as well as the availability of travel information), acceptability (relates to the standards of transport or the traveler where for example some people may not use a specific mode of transportation for lack of personal security or other), safety (concerned with reducing road and traffic injury and fatalities and improving road and pedestrian safety) and environmental sustainability (relates to the environmental costs and impacts associated with urban transport).

Parameters of Adequate Urban Mobility

Using those parameters to redefine mobility challenges encourages a more integrated and holistic form of planning where a variety of social, economic and environmental impacts are considered and it expands the range of modes considered from vehicle based modes to active transport such as walking and cycling.

To achieve a better understanding of the urban mobility landscape and to contribute to the debate on the “right to adequate mobility” in the GCR, this series of articles aims at critically examining the different dimensions of adequate and sustainable urban mobility. We aim to:

- Explore the different stakeholders in the sector and the governance framework in which they operate, given the importance of well-functioning institutions for the creation and maintenance of high quality urban mobility systems.

- Analyze how investment decisions for the sector are made, trace the flows of the money and critically assess the allocation of resources in the transportation sector.

- Examine the close links between transportation planning and urban planning.

- Draw lessons learnt from comparable cities around the world and reimagine solutions for the urban mobility sector in the GCR.

Works Cited

CAPMAS, 2012. “Early Report on Vehicle and Train Accidents – Year 2012.” Central Agency for Planning and Mobilization And Statistics. June 2013 Publication.

Ibrahim, J., Day, H.m Hirshom, J., and El-Setouhy, M., 2012. “Road Risk-perception and Pedestrian Injuries Among Students at Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt.” Injury & Violence Journal. Vol 4(2). pp. 65-72

WHO, 2009. “Eastern Mediterranean Status Report on Road Safety – Call for action.” WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean.

World Bank. (2006). Greater Cairo: a Proposed Urban Transport Strategy.

World Bank. (2014). The Cairo Congestion Study Executive Note.

Feature Image From (Els-creative commons)

Comments