Cairo 2050 Revisited: Nazlit Al-Simmān, Participation to Legitimize Elitist Planning

There are many doubts surrounding the General Organization for Physical Planning’s (GOPP) Cairo Strategic Urban Development Vision (CSUDV) regarding both the transparent and participatory nature of the planning process and whether it differs at all from the highly criticized Cairo 2050’s vision for the city. This article will look at the proposed CSUDV plan for the Pyramids Plateau and Nazlit Al-Simmān, an unplanned, low-income mixed residential and commercial area neighboring the Pyramids Plateau. Details of the CSUDV plan for the Pyramids Plateau and Nazlit Al-Simmān were extracted from the 23 June 2014 session conducted by the GOPP and the Environment and Development Group (EDG).1 The article then evaluates the manifestation of the participatory process adopted in this discussion session, which was held to present and discuss the findings of the socio-economic impact assessment (SIA) study conducted by EDG, on assignment from the GOPP.

The CSUDV project in Nazlit Al-Simmān, similar to Al-Fustāt in historic Cairo, shows how the state envisions the future of heavily populated areas of historic significance. This vision is based on evicting people by the thousands to “protect” the monuments and create aesthetically pleasing parks, boulevards, and open-air museums. It also demonstrates the state’s narrow understanding of participation. How can the government engage with local stakeholders to consolidate the state’s interest in promoting tourism and conserving heritage on one hand, if it ignores or discounts the economic and housing priorities of residents on the other hand, causing great suffering and increasing their vulnerability even further in these harsh economic times?

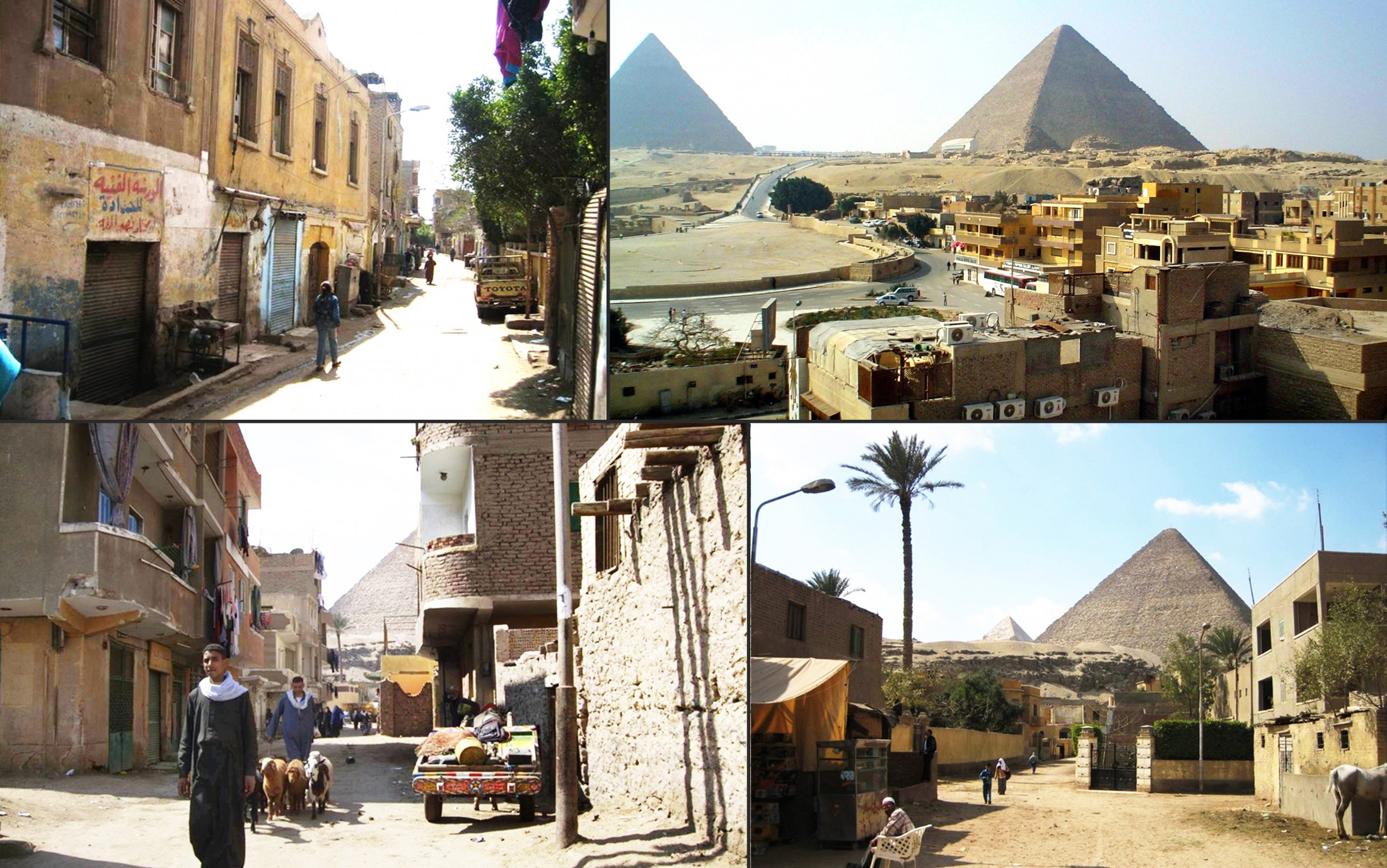

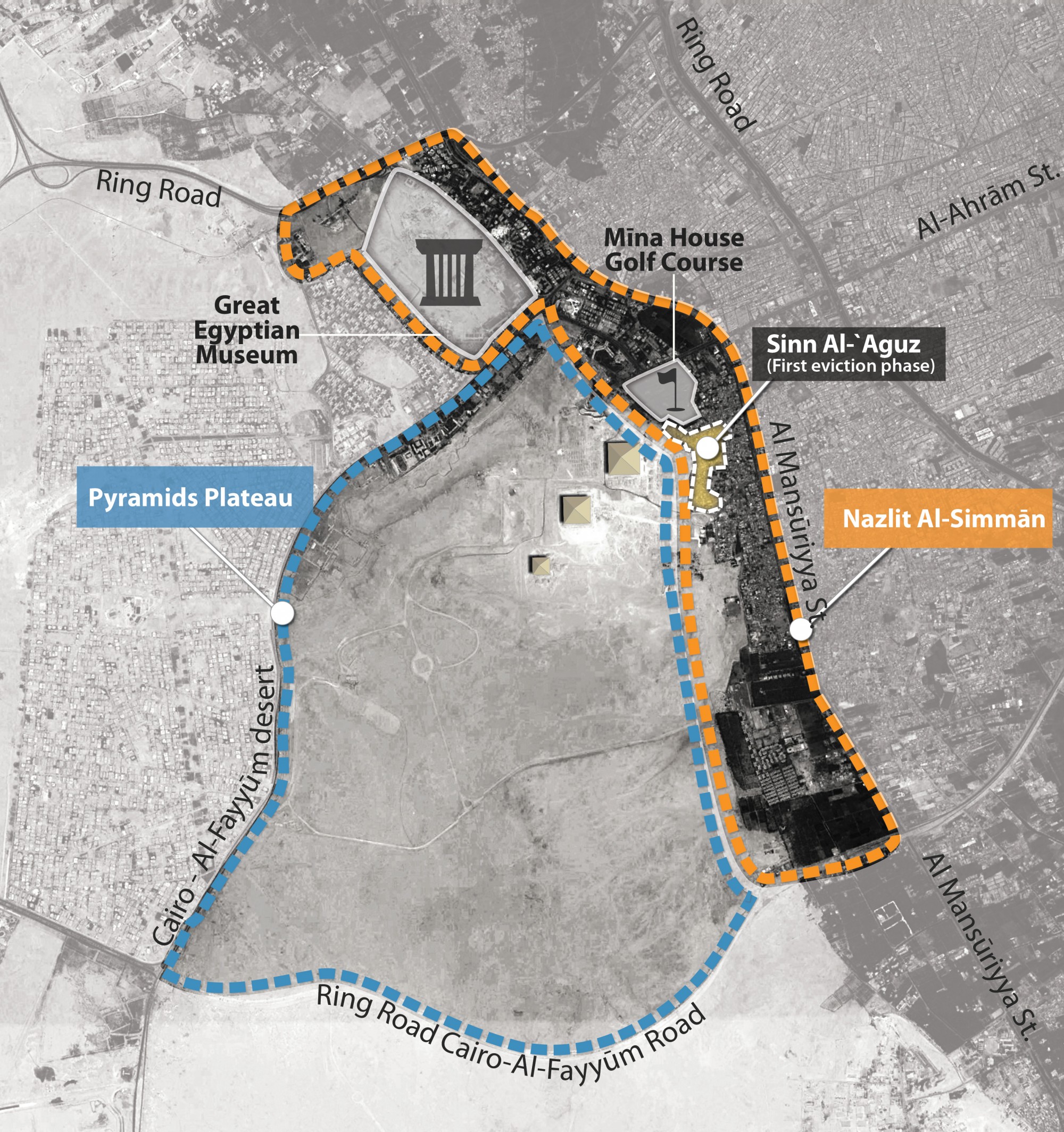

The global historic and touristic significance of the Pyramids Plateau distinguishes it from other CSUDV development projects, with stakeholders extending beyond local residents. Nazlit Al-Simmān is situated on the outskirts of the Giza Pyramids and the end point of the controversial Khufu Avenue proposed in one of the CSUDV’s 22 projects. Prior to modern planning in Egypt, Al-Simmān existed as a village providing services to tourists visiting the Pyramids, and during the urban expansion of the second half of the twentieth century it lost its rural characteristics and developed into an informal urban extension of al-Giza city that is still largely based on tourism for its economy. The vicinity of the Pyramids has long been a desirable development area, starting with Khedive Ismail’s development of al-Haram (the Pyramid) Road to ease the journey from Cairo up to the state’s current CSUDV plan.2

Further increasing the area’s desirability is the Valley Temple, a buried extension of the main entrance to the Pyramids complex, which will be excavated according to the proposed development plan. During the last decade of Mubarāk’s presidency, development plans were initiated by the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA), the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry of Housing’s (represented by GOPP) Cairo 2050 plan, but none have come to fruition.

Promoting tourism has been a central objective to policymakers, and as Egypt’s major tourist attraction, spatial policies for the development of the Pyramids area have been (and still are) strongly influenced by rationales of tourism rather than preserving heritage for the people3. ZahīHawwās, Head of SCA at the time, in an effort to regain the ‘sacredness’ of the Pyramids,constructed an eighteen kilometer-long fencearound the Pyramids Plateau in 2002 to isolate the area from urban life in a first step to remove all forms of informality, housing and commerce, in the vicinity of the Pyramids Plateau. In 2009 during the cabinet of Ahmed Nazīf, the last serving prime minister with Mubarāk before the 2011 revolution, Mustafa Madbūlī, the head of the GOPP at the time and the current Minister of Housing (2014), revealed government plans to remove all informal housing in NazlitAl-Simmānand neighboring informal areas surrounding the Pyramids Plateau, and to relocate their residents. In an article in Al-Ahram newspaper, Hawwās expressed his appreciation for Nazīf’s interest in tackling the “visual pollution” that is Nazlit Al-Simmān.The current CSUDV interventions for Nazlit Al-Simmāndo not differ significantly from the original Cairo 2050 plan made public in 2009, despite government promises to revise the plan to limit the highly-criticized mass evictions it entails. Both plans depend on the relocation of informal settlements surrounding the plateau and developing the area to supposedly ‘maximize’its economic potential.

One of the CSUDV’s explicit goals is to eliminate urban sprawl around the Pyramids, clearing out over 50,000 residents in Nazlit Al-Simmān. Little to no information has been made public on the government’s eviction, compensation, and relocation plans.The livelihoods of most residents will surely suffer since the majority of Nazlit Al-Simmān’s economic activity is dependent on tourism related to the Pyramids. Despite the informal nature of housing in the area, Nazlit Al-Simmān is also home to some very wealthy families, most – if not all – of whom are tourism tycoons with strong ties to the government and parliament.The majority of touristic and commercial activities in the area are controlled almost exclusively by these influential families.They benefit financially from the status quo and limited state interference indirectly affirms their social dominance. On the other hand, the average resident is from a low-income household, most probably living in an informally built area, renting their apartment, and working for one of the aforementioned families. This imbalanced power dynamic, coupled with legal insecurity which has increased since 2011, makes gaining residents’ buy-in and acceptance of the CSUDV plan ever more crucial. Yet Al-Simmān proved to be one of the most difficult areas for the GOPP and EDG to engage residents.

Project Details

The strategic vision for the Pyramids Plateau is to transform it into a world-class tourist destination and develop the area between the Pyramids and the Grand Egyptian Museum into an open-air museum that include sparks,a boulevard, and plazas. According to the CSUDV, this vision will be realized through a development plan that is designed to protect the historic area from urban encroachment, boost commercial activities in the area, address mobility challenges for visitors and residents, and the local standard of living. According the GOPP’s published booklet on the CSUDV, “The Strategy for the Urban Development of Greater Cairo – Future Visions and Strategic Directions,” the CSUDV will raise residents’ standard of living in NazletAlSimmān through integrated development (social, economic and environmental) that offers access to infrastructure and services. It is however unclear how local residents of Nazlit AlSimmān will reap these gains since the proposed interventions prioritize the eviction and relocation of the local population to make space for development projects to serve tourism.

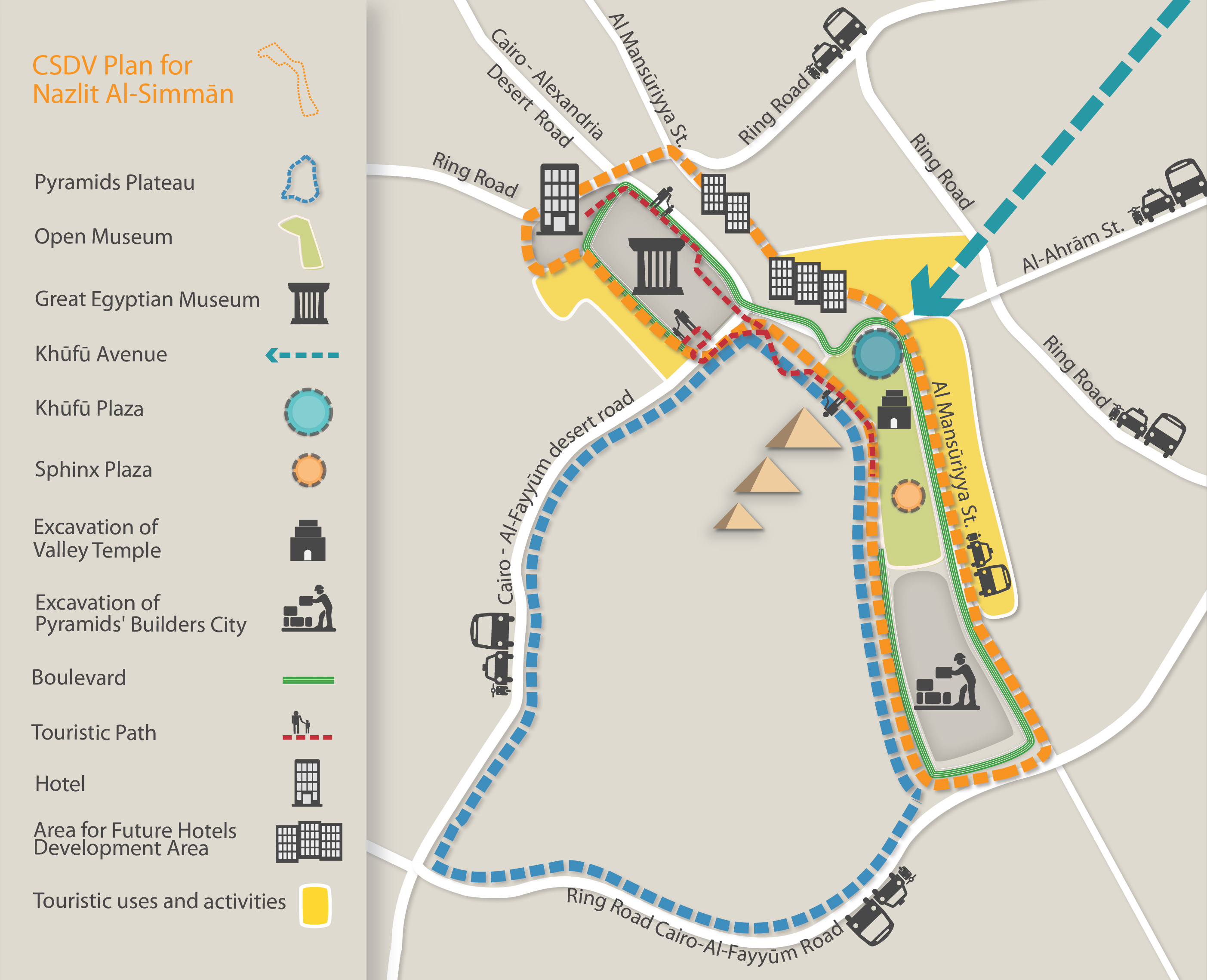

The development of the Pyramids Plateau and Nazlit Al-Simmān includes the following projects highlighted in the following map: the Grand Egyptian Museum Park (170 feddans), a hotel area (56 feddans), the Khufu Plaza (27 feddans), a touristic boulevard (3km), as well as 143 feddans designated for future hotel development.4

CSUDV Proposed Interventions for the Pyramids Plateau and Nazlit Al-Simmān

(Source: Recreated from the presentation at the Nazlit Al-Simmān SIA discussion session. June 23, 2014)

One of the plan’s stated design goals is to eliminate any structures that obstruct the view of the Pyramids, particularly in the vicinity of the Grand Museum and Pyramids, and surround both with plazas and green spaces. To create this oasis,53,392 residents from NazlitAl-Simmānwill be relocated over a period of six years and EGP 1.5 billions dedicated to support the eviction sand the compensation and relocation of residents.We cannot estimate the extent of these forced evictions across the community since the official population count of Nazlit Al-Simmān isn’t publicly available, but obviously these plans will impact a great number of people.

According to Dr. Ahmed Yousry, the lead designer of the CSUDV plan, evicted residents are to be compensated or relocated to new housing units on several vacant pieces of land owned by the state or land managed by the Egyptian Awqāf (Religious Endowments) Authority. The exact location of these lands was not discussed, however Dr. Yousry’s presentation included a map that highlighted several potential relocation areas east of the Ring Road (approximately four kilometers east of Nazlit Al-Simmān), an area near the Ring Road and Mariutiyya Road intersection (approximately three kilometers southeast of Nazlit Al-Simmān), and an area seven kilometers west of Al-Simmān.Final agreements have not been reached to allocate the above mentioned land plots for alternative housing. It is worth noting that these types of agreements are often problematic and complicated,bureaucratic and inter-agency skirmishes delay pending projects.5

The eviction and relocation of residents will impact 53,392 residents in total over five phases, who will need 12,973 housing units and 242 units for commercial activities. Sin Al-`Agūz, a low-income area to the north of Nazlit Al-Simmān(highlighted in the first map) and its 7,760 residents will be the first to be evicted and relocated over a period of two years. Sin Al-`Agūzhas many deteriorated buildings and is classified by the Informal Settlement Development Fund (ISDF) as a level two unsafe area, built on land owned by central agencies.6 In addition to residents’ eviction, the development plan will clear the Mena House golf course – East of the Giza Pyramids, which has been closed for several years for renovations,7 in order to develop Khufu Plaza.8 Interestingly, the operations manager from the Mena House Hotel stated during a phone interview that she was unaware of the GOPP’s development plan and that to her knowledge the hotel is continuing its plans to renovate and reopen the golf course in a few years.

The eviction and resettlement data shared during the presentation contained several gaps of information. For instance, the resettlement plan stated that 12,973 housing units would be needed, whereas the development plan (a ten-year period) stated that only 5,848 units will be constructed, with no reference to how the remaining 7,125 housing units are provided to residents. Given the state’s less-than-stellar history of relocating and fairly compensating residents who have been evicted, we do not expect a minimally disruptive, fair, and adequately compensated relocation plan will be a priority for the government.

The Meeting

On June 23, 2014 EDG conducted an invitation-only session to discuss the findings of the socio-economic impact assessment of the proposed development project of the Pyramids Plateau and Nazlit Al-Simmān.9 As with the previous consultation meetings, officials from the GOPP and UN-HABITAT were in attendance in addition to other invited government representatives and professionals in tourism, antiquities, urban planning, and cultural heritage. Also in attendance were housing rights activists and members of the Urban Reform Coalition.10

However,unlike previous discussion sessions focused on other projects, local residents were not present.EDG had only invited Nazlit Al-Simmān’s influential families, not representatives of the average resident. According to EDG, the prominent families decided to boycott the meeting after hearing “rumors” that the entire area was to be demolished, despite EDG’s clarification of the meeting’s purpose.The influential families were presumably also annoyed by the odd location chosen to hold the session – in downtown Cairo, over 20 kms away from Nazlet Al-Simmān.And even if some community members had attended the session, thousands of other affected residents would still be in the dark about the project, since there is no channel for them to access this highly-secured, if not secret, information.

According to Dr. Mostafa Saleh, co-founder of EDG, the socio-economic impact assessment is conducted through a four-step process: defining potential positive and negative impacts and prioritizing them according to their forecasted impact; offering preliminary solutions to address negative impacts and discussing them with local residents (through discussion sessions); creating the plan to mitigate negative impacts; and setting a monitoring and evaluation plan that will feedback into the mitigation plan.

Despite the fact that the purpose of this meeting was to present the findings of the SIA, EDG did not present any quantitative results of the study, such as quantifying residents’ responses towards relocation or the percentage of local residents whose primary income-generating activity will be severely compromised. According to EDG, they conducted quantitative and qualitative surveys in the area as a basis for their SIA analysis, however minimal data and analysis conclusions were shared. As such it is difficult to evaluate the comprehensiveness of their SIA of the CSUDV on Al-Simmān. The PowerPoint presentation included information regarding the number of residents to be evicted, the number of housing units needed to absorb them, and the cost of relocation. However figures presented were barely visible and the slides were glossed over by the presenters with no clarification or discussion. The only figure repeated during the presentation was the number of Sin Al-`Agūz residents who would be the first to be relocated. It is possible that the presenters preferred to focus on the first phase of relocations (7,760 residents) as opposed to bringing to our attention the total number of relocations planned (53,392 residents).

Previous discussion sessions conducted for other areas had their shortcomings which were discussed in an earlier TADAMUN article, but at least the authorities presented the socio-economic impact studies in the earlier meetings to the attending community members and proposed solutions to mitigate their negative impact. The Al-Simmān session didn’t even provide that information in sufficient detail. It was particularly surprising that the meeting wasn’t centered on the socio-economic impact and mitigation measures since, according to EDG, a preliminary survey of the area was conducted to better understand its socio-economic dynamics. During the session TADAMUN suggested sharing the contents of this report with the attendees to form an enhanced and realistic understanding of social life in the area. However, the study is unlikely to be circulated outside of government circles due to confidentiality agreements with the GOPP.

The purpose of socioeconomic impact assessments is to provide decision-makers and directly-impacted stakeholders with the information needed to make an informed and fair decision about the proposed project, whether any adjustments should be made to its design, or whether the project should be rejected because of adverse effects on the local population’s social and economic welfare. As illustrated above, EDG and indirectly, the GOPP, ignored this critically important component of any mega-project’s design, leaving the public (in its diversity) without the analysis and information needed to understand and negotiate about the project’s design, implementation, or adverse effects.

The consultation however, did open the door for civil society organizations to share their concerns about the public availability of information and data, especially information about the CSUDV’s planned interventions for the area which, they argued,did not differ much from the Cairo 2050 interventions proposed in 2009—a claim that was affirmed by Dr. Yousry.Although there were time limitations, the presenters should have shared more detailed information on the SIA findings, rather than using up valuable time to discuss the project overview. During the discussion period, feedback was given to EDG to provide participants with the project overview before hand in order to utilize the consultation meeting for a deeper discussion on the SIA and solutions to mitigate negative impacts.

Overall, the meeting failed to fulfill its main purpose according to EDG’s SIA process and the CSUDV literature:local community participation in engineering development alternatives for their area. Firstly, the local community members invited represent a minority of the local population, the elite, while the rest were excluded from the discussion. And then those who were invited boycotted the meeting – a first compared to the discussion sessions conducted in other areas. Second, while EDG acknowledges that it is still developing the project’s detailed outlines, the SIA analysis presented was shallow and lacked quantitative data from the study, sharing little evidence of a comprehensive analysis of a wide range of potentially negative outcomes.

Finally, even if one temporarily ignores the absence of the local community’s voice in this session, it is still unclear whether the issues raised in the meeting by participants will have a real influence on the CSUDV interventions in the area.If these sessions were truly intended to allow for local communities to participate in the democratic management of their city, mechanisms would be in place for the affected communities to influence the development plans, instead of the current passive exchange of (carefully selected) information. The GOPP is under no legal obligation to adopt EDG’sSIA recommendations.Second,the Minister of Housing recently announced that he is forming a committee, with representatives from the Ministries of Antiquities, Tourism, Awqāfand the newly-formed Ministry of State for Urban Renewal and Informal Areas, to present the project implementation plan to the Cabinet within a two-month period so that they can start implementing it as soon as possible.This shows that these ‘participatory’ sessions were not designed to actually allow any changes to the proposed plans.

1.As part of efforts by UN-Habitat and the GOPP to increase transparency and improve government-community relations in the wake of the negative reactions to Cairo 2050, UN-Habitat commissioned the private consultancy firm, Environment and Development Group (EDG), to undertake a Socioeconomic Impact Assessment (SIA) to gather residents’ opinions about and reactions to the five priority projects, and then transmit community responses to UN-Habitat and GOPP.

2.Kuppinger, Petra. 1998. “The Giza Pyramids: Accommodation, Tourism, Leisure and Consumption.” City and Society, vol. 1. June 1998.

3.Kuppinger, Petra.2006. “Pyramids and Alleys – Global dynamics and local strategies in Giza.” in Cairo Cosmopolitan Politics, Culture, and Urban Space in the New Globalized Middle East. Ed. Diane Singerman. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press.

4.Source: Presentation at the Nazlit Al-Simmān SIA discussion session. June 23rd, 2014.

5.For example, the Arḍ al-Liwa Community Park project discussed during TADAMUN’s The Role of Local Initiatives in Urban Development workshop, has been on hold for almost two years pending agreement between the Giza governorate (project implementer) and the Ministry of Awqāf, which owns the land.

6.ISDF Level 2 unsafe areas are ones characterized by unsuitable shelter conditions, which include buildings constructed with make-shift materials and sites unsuitable for construction.

7.The Mena House Golf Course was the first golf course in Egypt and is adjacent to the Mena House Hotel overlooking the Pyramids. A public sector company, EGOTH, the Egyptian General Company for Tourism & Hotels, owns the hotel.

8.Source: Presentation at the Nazlit Al-Simmān SIA discussion session. June 23rd, 2014.

9.EDG conducted three similar meetings to discuss the CSUDV interventions in Warraq, Matariyya, and Shubra Mazallat, which were discussed in a previous TADAMUN article.

10.The Urban Reform Coalition is a network of urbanists, rights groups, and concerned citizens that emerged in 2013 to monitor and reform urban development policies and practices in Egypt. It aims to do so through research; coordinating the activities of various actors in the urban sphere; and promoting collective organized efforts on the ground to achieve more efficient, equitable, and sustainable urbanization which foster the basic principles of the Right to the city and all human settlements.

Featured photo credits: GOPP (2009), “Cairo Future Vision 2050” Presentation.

Comments