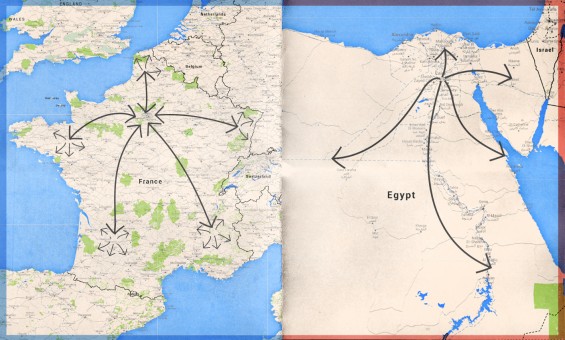

Comparing Two Forms of Local Administration: Can Decentralization in France be a Model for Egypt?

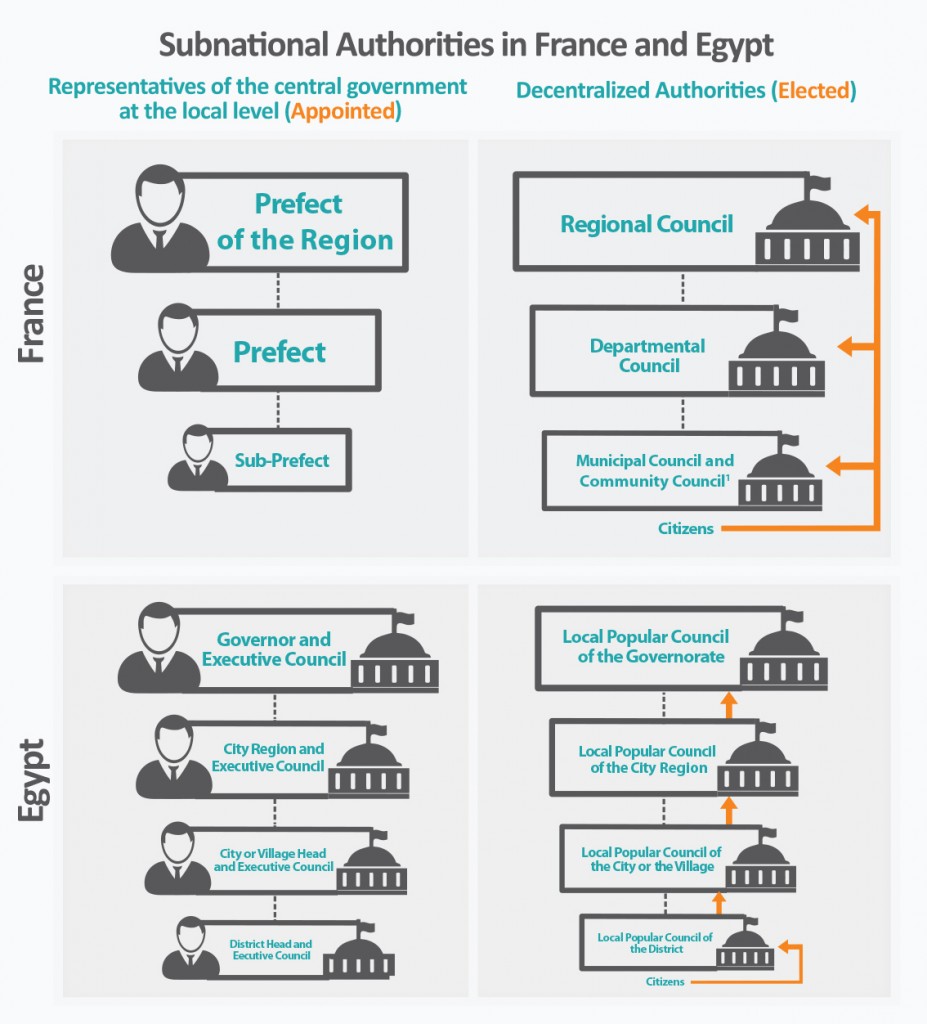

To begin with, it seems necessary to define some of the fundamental principles of the French model of government and its application in both countries. Egypt, like France, is a unitary state. Contrary to federal and confederate states, the central government in a unitary state is supreme and subnational authorities only exercise powers which the central government delegates to it. In unitary states, there are two types of subnational authorities: appointed and elected.

Appointed authorities are the representatives of the central government at the local level. In France, the appointed authorities are called the préfets (prefects in English). In Egypt, the appointed authorities are the executives of all local units: al-muḥāfiḍh (governor), rai’īs al-markaz (city region head), rai’īs al-madīnah (city head), rai’īs al-ḥaī (district head), and rai’īs al-qarīah (village head). Appointed authorities are the “deconcentrated” power of the central government. Deconcentration is the transfer of authority to local governments connected to the central power by the principle of hierarchical subordination (Baguenard, 2004). Their responsibility is to implement the policies and agenda of the central government.

Local elected authorities are representatives of local power. In France, these are the collectivités locales. In Egypt, these are the local popular councils. Elected authorities at the local level are the “decentralized” power. Decentralization is the transfer of responsibilities and resources to local, elected authorities.

Herein lies crucial distinction between the Egyptian and French states. Both are unitary states, both have strong central government representation at the subnational level, and neither government allows for legislative authority at the local level. However, the French model of government allows for strong local representation, which remains, as we will show within the course of this article, limited in Egypt.

The question of local representation is the central point in order to understand the logic and paradoxes of contemporary reform of local government in Egypt. We will briefly present the French system and its history before discussing the Egyptian system of local administration.

The Establishment of a New Local Administration System in France and Egypt

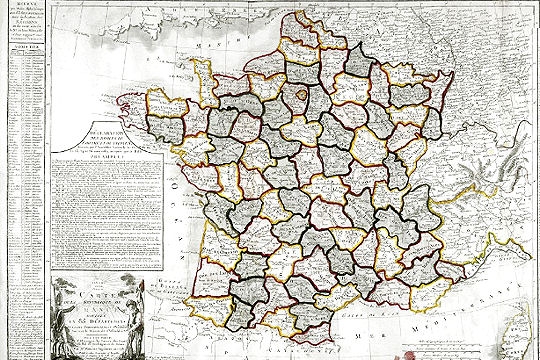

After the 1789 revolution, France was divided between two levels of local administration: the commune and the département. The Constituent Assembly established the commune, the smallest level of local administration. It followed a revision of the division between parishes. Considering their great number, more than 40,000 communes were created.2 In addition, the Constituent Assembly created 83 départements the second and highest level of local administration at that time.3 The management of this administrative level was entrusted to a council whose members were appointed by the central government. Hence, from the beginning, departments served the needs of the state and not the inhabitants. Napoleon Bonaparte (1768-1821) established the prefect system in 1800 for the same reason.

Map of the France’s départements in 1793 (Source: Passions et partage)

The prefects were the administrators of the départements (equivalent to Egypt’s governorates) in France and the French Empire. The sub prefects were the administrators of the communes. Both were appointed by Napoleon himself and served as his direct representative in the sub national levels of the state. Both were responsible for public order and good government and for ensuring that the policy of the central government was implemented effectively throughout the country. The power of the Prefect extended to “conscription, tax collection, agriculture, industry, commerce, public works, the fine arts, bridges and roads, public welfare, and public education” (Williams, 2002). The prefects also appointed the mayors and their deputies in municipalities with fewer than 5,000 inhabitants and made recommendations to the First Consul/Emperor (Napoleon himself), for the appointment of the larger municipalities. Napoleon called his prefects empereurs au petit pied, or “miniature, small-scale emperors.”

In order to consolidate his hold over the country and implement his innovative and controversial policies, Muḥammad `Alī(1805-1848) modeled the first modern administrative system of Egypt after the French system.

In 1826, Muḥammad `Alī divided the country into 24 provinces (mudīryāt, the equivalent of today’s governorates), with each subdivided into departments (m’amūryāt), districts (qism, plural: ‘aqsām) and sub-districts (khuṭ). This structure was superimposed upon villages that already existed in the previous local administration system. Like Napoleon’s system, the primary purpose of this system was to implement the policies of the central government, linking the villages of the country directly to Muḥammad `Alī himself through a cadre of loyal appointed officials. Mudīrūn and m’amūrūn were for instance required to send regular reports to Cairo enumerating all measures undertaken and requesting the viceroy’s approval. This system unified Egypt under one government, established control of rural areas of the country previously dominated by wealthy Mamluk households, boosted agricultural production, and allowed the central government to collect taxes more easily to fund national industrialization initiatives (Hunter, 1984).

Since Muḥammad `Alī created this system almost two hundred years ago, the size and responsibilities of the Egyptian government have expanded greatly. However, the power structure remains more or less the same. The Egyptian Constitution of 1923 gave governorates’ council sa legal status (Article 132). Considered as the first progressive Constitution of Egypt, it may have initiated an empowerment of local councils. However, the sweeping change that resulted from the reforms adopted by Gamal Abdel Nasser after 1952 did not modify the framework governing local administration (Nada, 2013).

Today, the President directly appoints all of the governors and the Prime Minister appoints all other executive positions at lower subnational levels of the government. All of these sub national executives are directly responsible to the president himself. The elected local popular councils,which first codified by Article 133 of the 1923 Constitution, then by Law No. (124/1960) and today by Law No. (43/1979) also remained largely subordinate to the central government.

While Egypt modeled its system of local government after the French system, France’s system has changed considerably from the time of Napoleon. Particularly since the 1980s, the state has progressively decentralized its authority to locally elected officials, while Egypt remains highly centralized.

The Evolution of the French Model

Several political, ideological, and economic factors led to the gradual decentralization of the French system and the reduced authority of the prefect. The first call for decentralization came from geographer Jean-François Gravier. Much like Cairo dominates Egypt, Paris dominates France. Gravier denounced this concentration of wealth and power in his book, Paris and the French Desert, published in 1947. He realized the corollary of this concentration of wealth was the gradual abandonment or “desertification” of other regions in France. His thesis sparked a debate about decentralization in France and moved the government to address the issue (Baguenard, 2004).

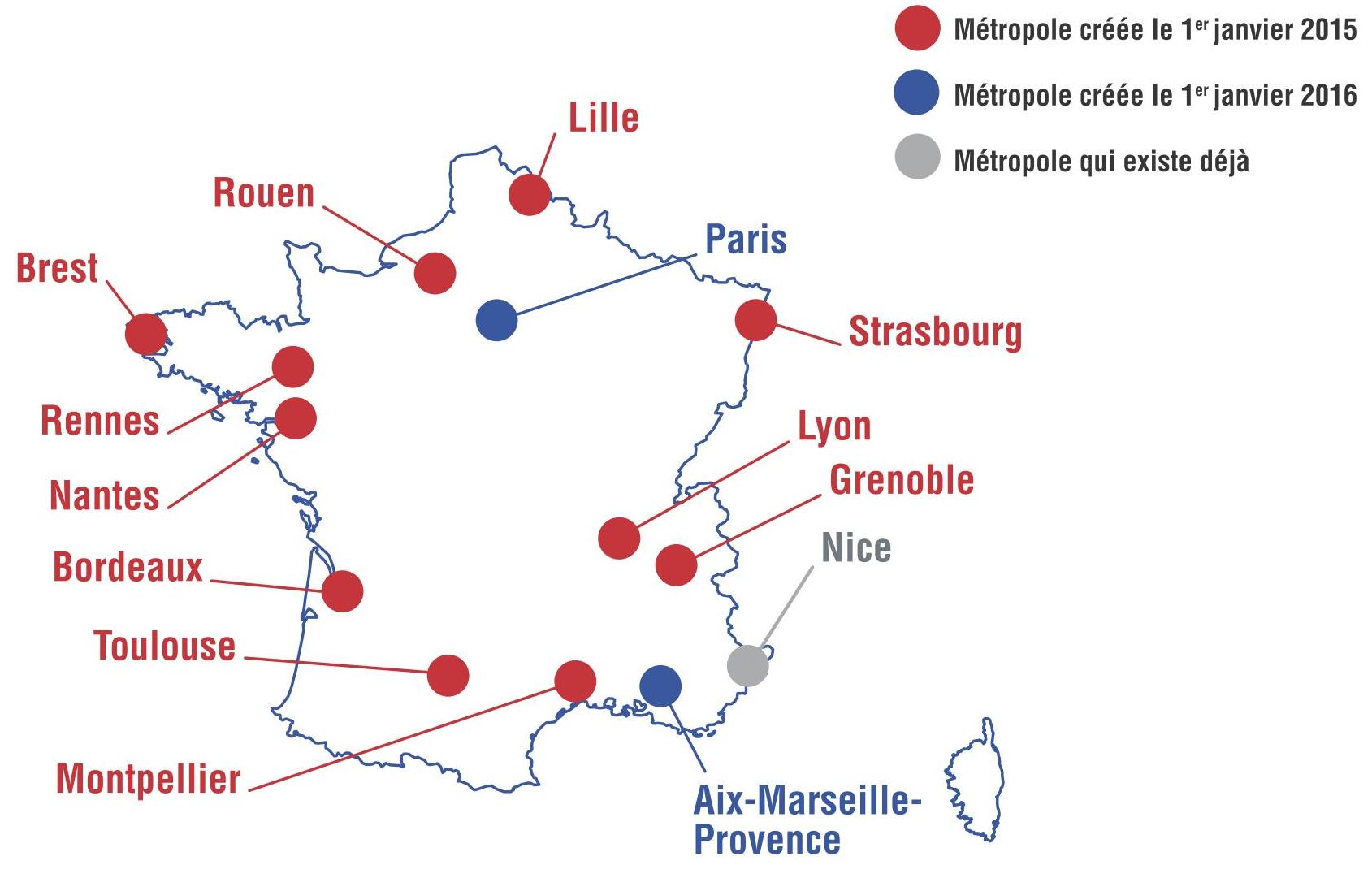

True to its nature, the French government adopted a centralized approach in an effort to re-balance the inequities in regional growth and power. It established a new public authority in 1963, the DATAR (Interministerial Delegation for Regional Planning and Regional Action) which was charged with ensuring a more balanced economic development. DATAR identified eight métropoles d’équilibre (balancing metropolises) to reduce the domination of the capital city – Paris – and to spur local economic development (Rochefort, 2002).

The results of this policy were mixed since it failed to slow down the growth of the Paris region. Nevertheless, it opened the way toward decentralization by suggesting that local power should have the financial and political means to create economic development. The Parliament’s first measure in that regard was establishing two new layers of local administration in 1966, which created four urban communities in the cities of Lille, Lyon, Strasbourg and Bordeaux. These are forms of association between communes – commonly designated by “intercommunality” – who band together for the provision of services such as waste collection and water supply. The government attempted to limit the fragmentation of municipal government due to the very large number of communes in France – more than 36,000. Other associations of communes were later created and a large majority of them are now included in a form of intercommunality. In addition, 22 établissements publics régionaux (regional public institution) were created in 1972. They were granted a legal status following the decentralization law of 1982 and became a new administrative level above the département.

Decentralization also received support from the central elites. The senior public servants who were most concerned with efficiency became aware of the need to adopt the multi-leveled political system. Doubtless, the European context favored these changes as several countries adopted institutional reforms which granted local authorities greater responsibility and autonomy.

Finally, in 1981 the victory of the Socialist Party in both the presidential and parliamentary elections for the first time since the 1940s provided the favorable ideological glue to implement decentralization. Since the 1970s, the party was indeed promoting the “transition to self-management” of local communities as part of their political platform (Gutiérrez Ruiz, 2012).4 The Socialists also won the 1975 departmental and 1976 municipal elections and had to answer to the demand for more autonomy coming from its constituency. They moved quickly to decentralize power and strengthen local authorities in case they might lose power in the next elections.

In 1982 and 1983, the central government, under President François Mitterrand (1981-1995) passed several decentralization laws (Baguenard, 2004). This “quiet revolution” – as this fundamental transformation of France’s state organization is often referred to – increased the financial and administrative independence of local councils. It gave them some form of decision-making capacity – what is designated in French law as “regulatory power” – without going as far as granting them legislative power.5

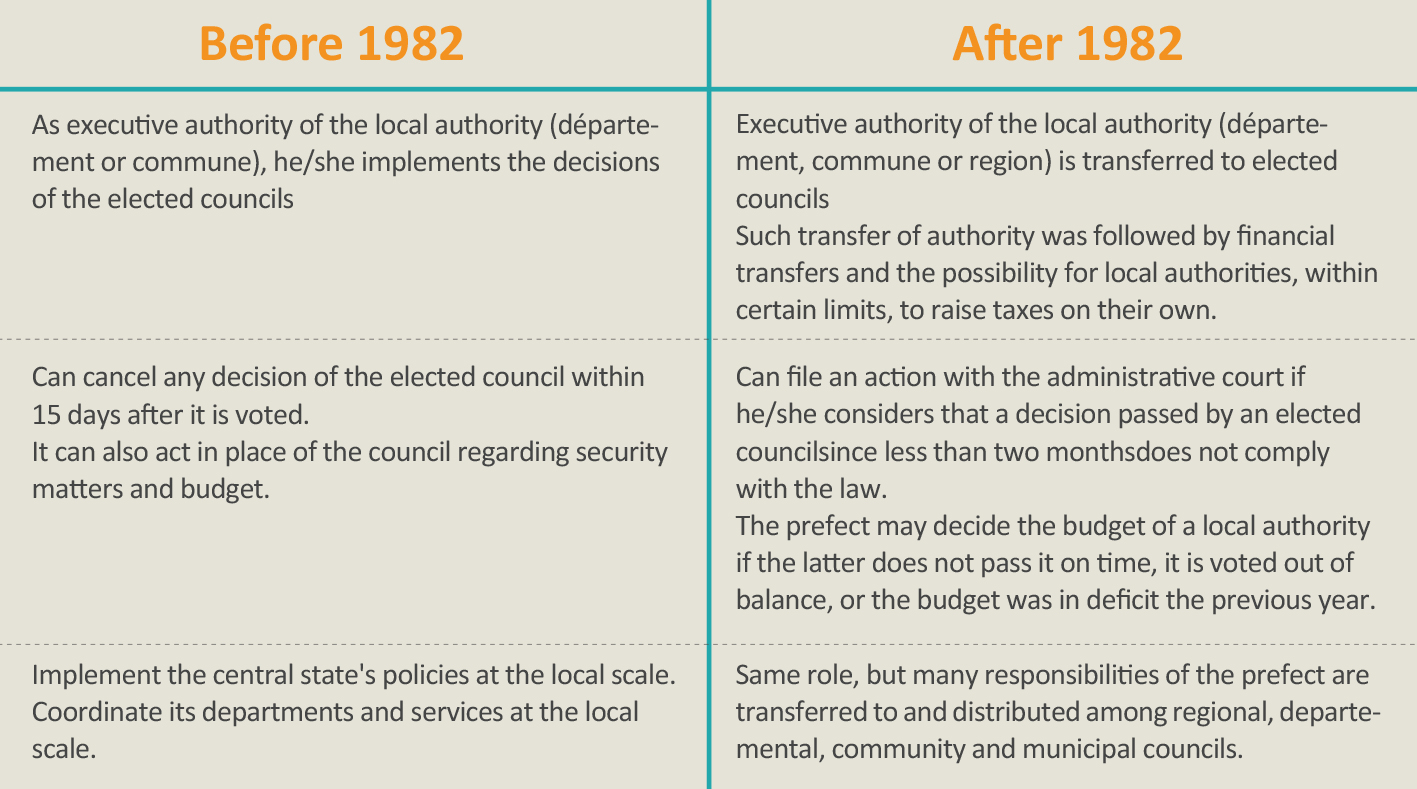

The Law of March 2, 1982 introduced three fundamental changes. First, it transferred the executive power of départements from the prefect to the president of the elected council. Second, as mentioned earlier, it granted a legal status to regions. As a result, the new regional council selected in 1986 were granted executive power and administrative independence from the prefect. Finally, the law removed the administrative supervision of the prefect in accordance with the principle of free administration of local authorities. Now, instead of making decisions independently, the prefect must refer disputes of legality to administrative judges (Frinault, 2012).

Responsibilities of the Prefect Before and After the First Decentralization Laws (Source: Vie-publique.fr and forum-scpo.com.)

In 2003, a few months after his election for a second term, President Jacques Chirac (1995-2007) announced another step toward decentralization. The reform was presented as a means to increase the efficiency of local administration. Since the 1990s, the superposition of different layers of local administration that have authority to intervene in all policy areas, and the lack of legibility as well as the increase in management and coordination costs, was one of the recurring criticisms addressed to the French administration system.6 The 2003 decentralization reform was expected to clarify the responsibilities of the different administration levels. However, the law was eventually limited to a mere transfer of responsibilities and financial resources to local authorities.

This out come has to be understood as a concession to an electoral clientele, that of elected local officials, who supported President Chirac in his reelection and were much more influential in decision-making processes at the national scale (Le Lidec, 2005). Following the adoption of decentralization laws, associations of elected officials – such as the powerful Association des maires de France (Mayors of France Association) – have been increasingly recognized and, in Parliament, the number of representatives holding another office at the local scale have increased (for instance an MP can also be a mayor) (Le Lidec, 2007).7

Instead of increasing the efficiency of local administration, the main effect of the 2003 reform seems to be an improvement of public service delivery along with cost increases. Indeed, a general effect of decentralization laws has been that elected officials tend to increase public spending in order to meet the demands of citizens regarding the quality of public services. On the contrary, central government civil servants, as they are not under threat of possible electoral sanctions, prefer to avoid excessive spending (Le Lidec, 2005).

Finally, since 2014, a new reform of local administration has been under consideration by the French Parliament. Once again, efficiency of public policy is presented as the main rationale for a reform whose first step was approved early January. The law, once voted, will create “metropolises” – a new form of intercommunality – in France’s 13 largest metropolitan regions. The second step, which was partially voted in November 2014, will reduce the number of Regions from 22 to 13 and eventually remove the département as a local government level. The third step, which is expected to be debated around 2020, is expected to clarifying and rationalize the distribution of responsibilities between the different local administration levels – communes, associations of communes, departments and regions8. It is too early to say if this set of laws will eventually improve public policy implementation at the local level. However, the passionate debate it has already created in Parliament confirms that the domination of central authorities that characterized local administration before the 1980s has indeed ended.

13 Metropolises (in Red and Blue) Created by the Law of January 27th, 2014 (Gouvernement.fr, 2014)

13 New Regions Created by the New Draft Law Currently Discussed in Parliament (Gouvernement.fr, 2014)

Overall, although the prefect’s role as the central government’s representative in the departement has not changed, the decentralization laws have redefined his or her mission to give greater power to elected representatives of the regional and departmental councils. The authority of the prefect is now limited to coordinating the implementation of state policies, maintaining security, and ensuring the legality and constitutionality of decisions taken by local councils. Likewise, citizens have increased their participation in local affairs through local councils which have become the real centers of power at the local scale. Such councils have improved public service delivery – in terms of education and road maintenance for instance –but they have also increased public spending.

The Prospects for Decentralization in Egypt

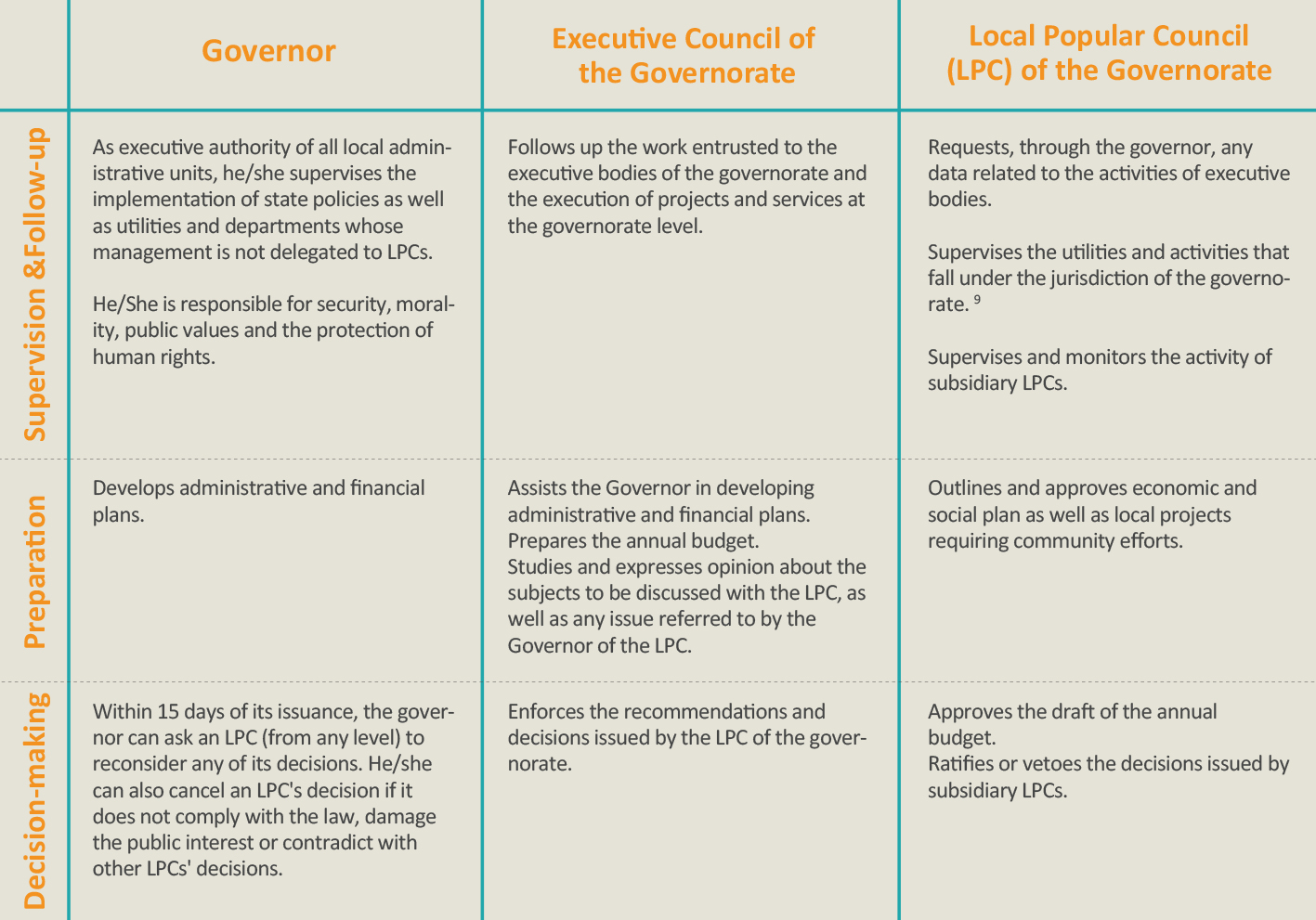

The situation in Egypt is quite different. On paper, the Law of Local Administration of 1979, enacted under President Anwar Sadat (1970-1981), was supposed to give greater powers to Local Popular Councils (LPCs) by giving them the authority to supervise all utilities as well decisions taken by the heads and executive councils of local administrative units – governorates, city regions, cities, districts and villages – who were all appointed by the executive branch. However, in practice, the LPCs had far less power than their responsibilities implied. As underlined in a previous TADAMUN article, the LPC supervisory role was more advisory (and optional) and any decision made by an LPC was subject to the approval of the higher-level LPCs and ultimately could be rejected by the governor if it did not conform to national policy. This limited decision-making power of local units in Egypt was reinforced by the scarce financial resources granted by the central government. It is estimated that only 12 percent of public expenditures were spent on local administration for the 2011/2012 fiscal year, compared to transition economy countries similar to Egypt that spend about 20 to 30 percent.

Following the 2011 Revolution, a new Constitution ratified in 2012 raised hopes that elected local councils would gain more autonomy.For the first time, a Constitution in Egypt dedicated a chapter to local administration with important rights established regarding the autonomy of local administrative units. Article 190 for instance stated, “Local Council decisions issued within the limits of its jurisdiction are final and not subject to interference from the executive authorities,” Article 191 stated that “every Local Council shall be in charge of its own budget and final accounts” and Article 192 stipulated that “it is prohibited to dissolve Local Councils.” Nevertheless, the extent of the decision-making authority of these local councils remained to be seen as they were still subject to state oversight “to prevent the Council from overstepping limits, or causing damage to public interests or the interests of other Local Councils” (Article 189, 2012 Egyptian Constitution).

Unfortunately, following another constitutional ratification in January 2014 – which maintains more or less the rights regarding LPCs established by the 2012 Constitution – anew draft law on local administration reinforces the centralized nature of the Egyptian state (read TADAMUN’s analysis of the evolution local administration legislation here). In a public statement, current Local Development Minister General Adel Labib stressed that the new local administration law will give broader powers to governors (who are chosen by the central government) – not local councils. Almost no new transfer of financial resources is included in the new draft law and decisions taken by LPCs can be reconsidered if they “damage public interest” (Article 20, Local Administration Law draft) – a very fluid term that can be used by the executive branch to veto any LPC decision. Within this context, the new mechanisms introduced – public hearings prior to the approval of local development plans, the possibility for LPCs to access to information and question appointed local officials – are unlikely to play their role and make the state more accountable. Overall, the new draft law underlines the reluctance of the government to take into account citizens’ views and opinions in the design and implementation of public policies, especially at the local level.

Summary of Governorates’ Responsibilities in Egypt according the 2014 Draft of LAL. (Sources: Draft of Local Administration Law of 2014; Nada, 2013.)

Conclusion

By comparing the French and Egyptian local administration systems and their evolution overtime, it seems we may be suggesting a blind application of the French model of decentralization. However, that is not the case since the French experience of decentralization has its own problems related to uncontrolled increases in public spending. In addition, it is now difficult for the central government to reform local administration and demand greater efficiency since local representatives can also hold legislative office as MPs and this dual mandate encourages them to lobby for local elected officials’ interests. Nevertheless, such issues do not apply in the short run to Egypt considering that, up to now, the local administrative budget is extremely limited and local representatives have near to no influence at the national scale.

On the other hand, decentralization in France has had many positive outcomes: it has greatly improved service delivery. As a result, roads have been better maintained, schools are better staffed, tramways and bus rapid transit systems have been built. This is the case because citizens’ claims are at the core of local elected councils’ concerns. Decentralization in France has therefore increased the accountability of the state and that is precisely what decentralization could bring to Egypt’s local administration system.

Contrary to what we could expect, decentralization in France was not, at first, a vertical process, or a top-down transfer of responsibilities. It rather consisted of the horizontal transfer of authority, at the local scale, from appointed representatives of the central government– the prefects – to elected citizen representatives. In Egypt, the authority remains with the central government representatives. Article 187 of the 2012 Constitution and article 179 of the 2014 Constitution in Egypt have left open the possibility of electing the currently appointed governors as well as city region, city, district, and village heads – a potential inlet for democratization at the local level. However, drawing from the French experience, some Egyptian experts have blindly argued that governors should remain appointed without properly comparing both systems.

Prefects are currently not elected and are not likely to be so in the short or long run, because their administrative supervision has been removed and most of their authority has already been transferred to the elected regional, departemental, community and municipal councils. As such, there is no need for the perfects to be elected, as they don’t hold decision-making power, which is not comparable to the situation in Egypt where governors hold the majority of the decision-making powers. Electing governors and other heads of local administrative units will not be required to implement decentralization if a similar transition of power to elected councils takes place.

On a final note, it seems necessary to underline that decentralization did not jeopardize the unitary structure of the state in France. No local council was granted legislative power, which remains the exclusive responsibility of the Parliament. In addition, the responsibilities of the prefect for the maintenance of public order have remained intact. Therefore, if the elected councils are now autonomous, that does not mean that they are independent. Contrary to what many argue, if decentralization takes place in Egypt, it is unlikely that it will lead to division of the country.

Works cited:

Baguenard, Jacques. 2004. La décentralisation, 7th edition. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France “Que sais-je”, 128 pages.

Catusse, Myriam, Cattedra, Raffaele and Idrissi Janati, M’hammed. 2007. “Decentralization and its paradoxes in Morocco.” In Driesken, Barbara, Mermier, Franck and Wimmen, Heiko (ed.), Cities of the South, London: Saqi Books, 113-135.

Nada, Mohamed. 2013. “Local Government Structure in Egypt: An In-Depth Look.” In ESCWA – Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia. Institutional, New York: United Nations, 77 pages.

Frinault, Thomas.2012. “La décentralisation : retour sur deux siècles de réformes.” Métropolitiques.eu, October 1st.

Gutiérrez Ruiz, Carolina. 2012.”Les trajectoires de décentralisation en France et au Chili : une approche comparée des ‘convergences’ et des ‘réappropriations’.”Revue internationale de politique comparée, 19(1), 115-137.

Hunter, F.Robert.1999. Egypt under the Khedives 1805-1879, From Household Government to Modern Bureaucracy. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, 2nd edition, 288 pages.

Le Lidec, Patrick. 2005. “La relance de la décentralisation en France. De la rhétoriquemanagériale aux réalitéspolitiques de ‘l’acte II’.” Politiques et management public, 23(3), 101-125.

Le Lidec, Patrick. 2007. “Le jeu du compromis : l’Etat et les collectivités territoriales dans la décentralisation en France.” Revue française d’administration publique, No 121-122, 111-130.

Rochefort, Michel. 2002. “Des métropoles d’équilibre aux métropoles d’aujourd’hui.” Strates, special issue.

Rivlin, Helen Anne, B. 2014. “MuḥammadʿAlī.” Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Williams, Robert D.2002. “Napoleon’s Administrative Army – His Prefects.” Member’s Bulletin: Napoleonic Society of America, No 72, 15-20.

1.Muḥammad `Alī (1769-1849) was pasha and viceroy of Egypt under the Ottoman Empire (Rivlin, 2014). He is regarded as the founder of modern Egypt because of the extensive reforms in the military, economic, and cultural spheres that he instituted.

2.This number has been reduced to about 36,000 communes today.

3.There are 101 départements in France nowadays.

4.Self-management endorses a greater role for workers or citizens in decision-making. Self-management is a characteristic of many models of socialism, with proposals for self-management having appeared many times throughout the history of the socialist movement, advocated variously by market socialists, communists and anarchists.

5.The regulatory power is the power for executive and administrative authorities to unilaterally take binding acts of general and impersonal nature such as decrees and “circulars”. It is carried out “in accordance with the law.”

6.The four layers of local government are the region, the département,the community of communes and the commune.

7. About 85 percent of representatives in the French Parliament’s two houses – the Senate and the National Assembly – hold an elected position at the local level.

8.For more information on the distribution of responsibilities between the state and local authorities, please visit this page.

9.The utilities and activities are neither specified in the local administration law of 1979 nor in the draft law.

Related Links:

على الدين هلال. 2009.”لماذا لم تتحقق اللامركزية في مصر“, الأهرام اليومي, 12 ديسمبر

The Connexion. 2010. What exactly does a préfet do?

Royal Decree No. 42 on Building a Constitutional System for the Egyptian State. 1923.

مسيرة عبد الحق ولينا عطالله. 2014. “مقارنة بين دستور 2012 ومشروع دستور 2013“, مدى مصر, 13 يناير.

Tadamun. 2014.”3. Local Level”, Know your Government.

Comments