Decentralization and Women’s Representation in Tunisia: The First Female Mayor of Tunis

After the Arab Spring, a major opportunity opened to secure women’s rights in Tunisia, and these efforts are reflected, amongst other places, in the makeup of women in political offices at both the national and the local level. In October 2011, Tunisians voted for the Constituent Assembly which was charged with drafting a new constitution. Tunisians, unlike their Egyptian counterparts, took three years to debate and deliberate about the new constitution. Women in Tunisia used the participatory constitution making process “as a vehicle for mobilizing local efforts, connecting with gender rights advocates in other MENA countries, and participating in a transnational dialogue” (de Silva de Alwis, Mnasri, & Ward, 2017, p. 91-2). One result of these efforts are gender quotas, important mechanisms for achieving gender parity. Gender quotas in Tunisia are not entirely new. Prior to the Arab Spring, voluntary party quotas led to relatively high levels of women’s representation (discussed in more detail below). However, legislative bodies were dominated by the ruling party. Quotas at this time were also not specified in electoral law as they are today. After the Arab Spring, Tunisia employed gender quotas for the 2011 National Constituent Assembly (NCA) elections, the 2014 parliamentary elections, and the 2018 municipal level elections, helping to ensure women’s representation in legislative bodies at all levels of government.

Tunisia’s electoral law requires both vertical parity (meaning that male and female candidates alternate within each party list) and horizontal parity (which requires that parties put forward an equal number of male- and female-headed lists across districts or municipalities). The progressive gender quota as well as other guarantees of women’s equality enshrined in the new Tunisian constitution are an outcome of bottom-up feminist organizing and activism interacting with accommodating elites. A “politics from below” fueled by large-scale protests and women’s groups during the constitutional drafting process forced a change in the constitution from language about the “complementarity” of women in Article 28 to the equality of women, who as a group, should be afforded equal rights (Charrad & Zarrugh, 2014, p. 230). By 2019, women held nearly a third of parliament and almost half of local council seats (UN Women, 2018). However, as we discuss below, mayoral races lack gender quotas, which has implications for the representation of women at this level. Quotas have increased female representation in legislative bodies, but the lack of quotas for executive level positions keeps women at a disadvantage.

While Tunisia has experienced important gains when it comes to women’s representation, where Tunisia has been arguably been less successful, thus far, is with democratization at the local level and the decentralization of power, especially political power. The constitution is somewhat vague with regard to how much power local governments should have, in spite of its commitment to decentralization (discussed below). Still, the recent municipal-level elections in 2018 opened up opportunities for women’s participation across Tunisia. In this brief, we explore both decentralization and women’s local representation, and discuss the rise of Souad Abderrahim, the first female mayor of Tunis. She is representative of a larger trend of increasing female representation at the local level and her tenure as mayor offers a window through which to explore the decentralization process under the new constitution. We outline the powers that local governments have and argue that although these might be limited, women’s representation in local government still carries strong symbolic value and has the potential to affect future changes, especially as women gain more political experience.

Souad Abderrahim, amongst other women elected to local government, is a strong advocate for decentralization and is in a position to claim greater powers for local governments. Decentralization may be a useful tool for alleviating Tunisia’s regional disparities, a major driver of the revolution. And women, who make up nearly half of the positions in local government, may be part of the solution to these disparities. New female representatives may be more likely to translate citizens’ demands into action.

Decentralization and Tunisia’s Constitution

It is not always the case that democratic transitions at the national level lead to democratization at the local level. Local governments in Tunisia have some administrative and fiscal powers, but political power—that is the power to make policies—remains highly centralized eight years after the revolution, even though decentralization was a major issue during the drafting of the new constitution. Administrative decentralization is concerned with the organization of political institutions and how these institutions execute policy decisions, turning policies into outcomes. Fiscal decentralization refers to who sets and collects taxes, as well as who undertakes expenditures. Finally, political decentralization entails issues of representation and the capacity of local governments to make policy, “the extent to which political institutions map the multiplicity of citizen interests onto policy decisions” (Litvak, Ahmad, & Bird, 1998, p. 6). Political decentralization cannot exist without the other two types, but it is only through political decentralization that meaningful democratization at the local level can take place.

Administrative decentralization has a relatively long history in Tunisia, but central authorities, whether colonial or authoritarian, have utilized the municipality system as a means of wielding influence over the local level. Tunis was established in 1858 as the first municipality both in Tunisia and in the Arab world as a whole. For about three decades, Tunis was the only municipality until an additional six were created in 1884. French officials utilized decentralization as a tool for territorial and colonial control and the number of municipalities grew to a total of 69 by the end of the colonial period (UCLG, 2007). During the Ben Ali period (1987-2011), the government exerted its influence at the local level through various forms of oversight, severely reducing the role of municipalities (Clark, Dalmasso, & Lust, 2017).

On paper, the municipalities were responsible for social, economic and cultural development, service provision, urban planning, public spaces, and the management of local police services such as traffic control. Over time, their responsibilities dwindled to very basic service provision, primarily, trash collection. Moreover, municipal authority often overlapped with the powers of the governorate, which ultimately superseded the decision-making power of the municipality. Municipalities had no real power over their budgets and struggled to raise their own revenue, becoming more and more dependent upon the state. This financial dependence led to higher levels of state involvement in local decision-making (Clark, Dalmasso, & Lust, 2017). Their political power was also hampered by the ruling party’s control over local councils. While Organic Law No. 90-48 of 4 May 1990 introduced a mixed poll method for local elections for the first time, “the ballot method [gave] the dominant party a greater advantage and [put] other parties at a disadvantage” in spite of the fact that “it was presented as a concession in favor of opposition parties” (UCLG, 2007, p. 3). The electoral laws allowed the ruling Constitutional Democratic Rally (RCD) to consistently win 80 percent of municipal council seats.

Immediately after the 2011 revolution, activists made replacing the RCD-dominated councils a top priority; however, the local-level Special Delegations (SDs) that replaced the municipal councils in the aftermath of the revolution became sites of elite power struggles, illustrating that democratization at the local level would be hard-won (Clark, Dalmasso, & Lust, 2017). There were also intense debates about decentralization in post-revolutionary Tunisia. Opponents viewed it as a slippery slope towards fractionalization, regionalism, and the overall disintegration of the unity of the state. However, proponents comprised the majority and argued that more equitable economic development between regions should be a major priority in the constitutional reform process given that these disparities were one of the most important driving forces of the revolution.

Eventually, proponents won out and Article 131 of the Tunisian Constitution states definitively that local government is based on the principle of decentralization. It also states that:

- Municipal elections shall be direct, free and fair, as well as allow for youth participation (Article 133)

- However, district-level elections remain indirect elections

- Local authorities enjoy financial and administrative independence (Article 132)

- Yet, this does not guarantee political independence

- Local authorities enjoy regulatory powers (Article 134), have their own resources as well as resources from the central government (Article 135), and can manage their resources freely within the budget that is allocated to them (Article 137)

- These powers ultimately, however, remain under the supervision of the financial judiciary.[1]

- Local governments should strive for participatory democracy in the preparation of its development programs and in implementation (Article 139)

- Still, the central government still plays a major role in the allocation of resources, so chances of participatory budgeting are extremely limited, although such experiments did take place in Tunisia in the aftermath of the revolution

Participatory budgeting, as a method of participatory governance, refers to a process of collaboration between civil society and local government to allocate municipal funds, as representative democracy alone is insufficient to engage citizens, properly allocate scarce public resources, and improve service delivery (Wampler & McNulty, 2011). To arrive at more inclusive, collective decision-making, direct democracy mechanisms alongside representative institutions give citizens more power over policies and a say in their implementation. Proponents of decentralization argue that decentralization opens up avenues for participatory democracy; however, this requires a sincere commitment to representation at the local level and dedicated financial resources.

Although there was an emphasis on decentralization and expanding the powers to local authorities in the constitution, municipal elections were postponed from the originally scheduled date in October 2016 to May 2018. The delays were a result of two wider legislative hurdles. The first was the failure to adopt the Law on Local and Regional Elections until January 31, 2017. The second was the delay in adopting the Code on Local Authorities until May 1, 2018. Although the elections could have been held using the Law 33 of 1975, it would have created a legal and practical confusion as Law 33 did not recognize the local authorities’ administrative and financial independence. So, without the code, “neither voters nor candidates for the municipal councils would know precisely what the council’s responsibilities are or what kinds of projects they will have the authority to implement” (Abderrahim, 2017).

Parliament finally adopted the Code on Local Authorities in May 2018, after a long period of debate over the specifics of how the new local councils should function. It clarified some of the confusion surrounding local governance and devolved power to local authorities for the first time since Tunisian independence; however, the extent of the power that local authorities actually have still remains uncertain. According to the code:

- Local authorities are declared “financially, administratively, and legally independent entities” that can challenge the central government in administrative courts. The centrally appointed governor (wali) was stripped of its veto power over local authorities. Under the current code, the wali can only challenge local authorities and their decisions through the administrative courts.

- Local authorities are responsible for developing, approving, and implementing their own annual budgets. Revenues are comprised of local taxes and fees, national transfers, loans, and grants.

- The central government will help local authorities become financially sustainable through internal transfers from the newly-formed Decentralization Funds through (1) credit allocations within financial laws (2) allocation of a proportion of tax revenues and (3) a proportion of governmental revenues from natural resource exploitation.[2]

- Local authorities are responsible for waste collection, road and pavement rehabilitation, street lighting, sewage systems, water and sanitation, and public spaces within their jurisdictions.

Overall, these changes grant more autonomy to the local level, especially compared to the oversight system of the Ben Ali era. Although the political power of local governments remains limited, they have much more control over their budgets, they can levy taxes and fees, and they are responsible for a wider array of service provision. Precisely whether or not the newly established decentralization funds will alleviate the dependence of under-funded municipalities on the state remains to be seen; however, the increased responsibilities of municipal councils represent an important accountability mechanism, one that is closer to the people than the central state.

The focus on decentralization in the constitution and in the Code on Local Authorities is a response to decades long policies of centralizing power, policies that resulted in uneven development and distribution of resources between areas. Economic disparities in Tunisia are regionally based; massive spatial inequalities exist between the northern coastal areas and the central west and southern regions. Starting in the 1980s and 1990s, the government launched “integrated development plans” with the goal of reducing regional inequalities, yet “these were not enough to change the main resource-allocation mechanisms or significantly reduce the level of inequality. Many institutions were created for the sake of regional development, but none of them could initiate and implement major comprehensive plans for the poor regions” (Boughzala & Hamdi, 2014, p. 4). The regional development plans were part of a “top-down enterprise, micromanaged by the state,” but “neither Bourguiba nor Ben Ali followed through on their declaratory policies to ensure specifically-allocated, regenerative investments that were directed toward deprived regions” (Sadiki, 2019).

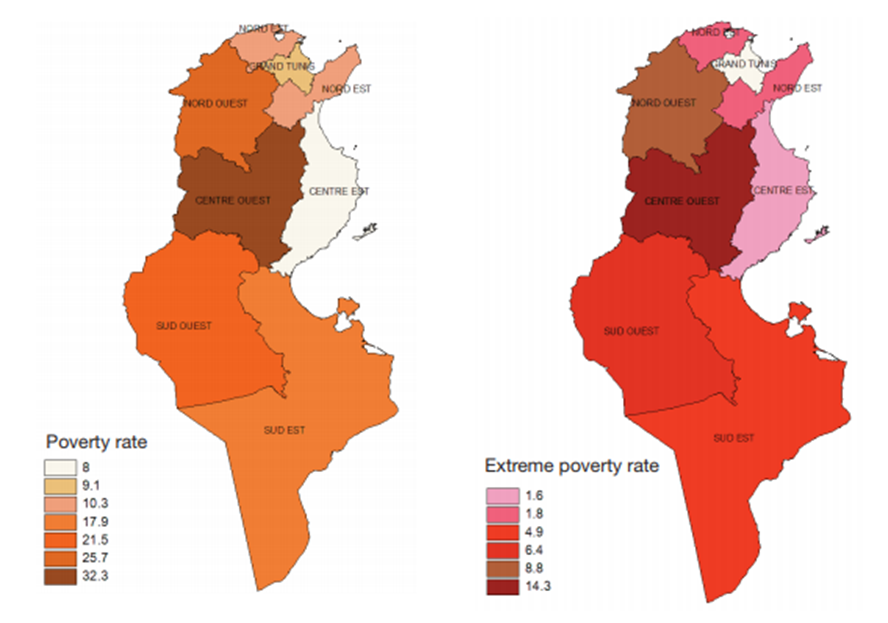

Figure 1: Poverty Rates and Extreme Poverty Rates by Region in Tunisia, 2010 (National Institute of Statistics, 2012, p. 16).

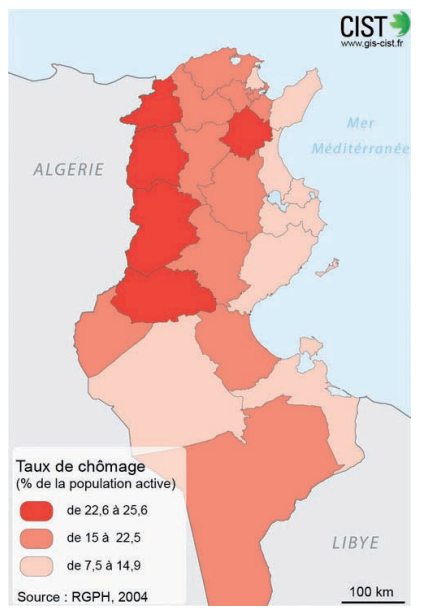

The result was that poverty and unemployment became regionally concentrated in specific areas. In the Center-West, 32 percent of people live under the poverty compared to 8 percent in the Center-East and 9 percent Greater Tunis regions (Figure 1). Unemployment rates in this region were also among the highest (Figure 2). This region was the epicenter for the 2011 protests, as well as earlier revolts against unemployment, working conditions and economic inequality (Beinin, 2015). To fulfill the demands of the revolution, political leaders would have to take reducing regional disparities seriously in the writing of the new constitution.

Ennahda’s surprise candidate: Souad Abderrahim

After the 2011 revolution, the Islamist party Ennahda won 89 out of 217 seats in the National Constituent Assembly (NCA), tasked with drafting the new constitution (NDI, 2011). The NCA established six commissions to write the constitution and Ennahda chaired four of them, giving them a central role in the constitution making process.[3] One of the commissions specifically addressed issues of local governance, reflecting the importance of the decentralization issue in the restructuring of the political system. The secular Nidaa Tounes, which won the second largest percentage of seats in the NCA, expressed skepticism about devolving power to the local level given that its support derived from the coastal regions and traditional elites. In contrast, Ennahda’s base is centered in the interior regions and as a result backed decentralization “to counterbalance the traditional power bases in Tunis” (Walles, 2018).

Tunisia held its first free and democratic municipal elections on May 6, 2018. More than 57,000 candidates competed for over 7,200 open seats across 350 municipalities. Free, fair and direct election for so many positions is significant in and of itself, but the first municipal elections were significant for another reason. Nearly half of the candidates—49 percent—were women and over half of all candidates were under the age of 35. Forty-seven percent of female candidates won election, and 37 percent of youth did (Carnegie, 2018). A large proportion of the female candidates were young people. A survey of 2,000 candidates for municipal elections found that the mean age for male candidates was 45 years old and the mean age for female candidates was 36 years old (Blackman, Clark, & Şaşmaz, 2018). Even if this gap is a result of party leaders attempting to fulfill both the youth quota[4] and the women’s quota[5] at the same time, it still opened up opportunities for young women to participate in politics.

In the 2018 local elections, Ennahda was the only party that fielded candidates in all 350 municipal districts (Nidaa Tounes fielded candidates in 345 districts, and the left-wing Popular Front in 119). Ennahda’s penetration of the entire electoral map is evidence of its ability to mobilize at the local level and get results (Feurur, 2018). While Nidaa Tounes relied on establishment party members, some of whom were former RCD members, Ennahda brought new political candidates in, requiring that half of the party lists be open to people new to politics.[6] In regions that were not Ennahda strongholds, “the party recruited surprising names, such as unionist women, former high-level bureaucrats and representatives of religious minorities.” (Şaşmaz, 2018).

Perhaps the most surprising result of the local elections was in Tunis, where Ennahda nominated Souad Abderrahim for mayor. Abderrahim started her activism on campus starting in 1985 as part of the General Union of Tunisian Students (UGTT) and is a strong advocate for decentralization. Municipal councils elect the mayor during their first session, in a two-round election which requires the winning candidate to receive an absolute majority. Historically, the laws governing mayoral selection differed between Tunis and the other municipalities. Until the Organic Law No. 90-48 of 4 May 1990 which introduced local level elections, central authorities appointed all mayors. After the passage of the 1990 law, local councilors elected the mayor in all other municipalities. However, the mayor of Tunis remained an appointed position until the May 2018 municipal elections. Thus, it is significant that the very first elected mayor is a woman, demonstrating that a majority of the political elites on the Tunis local council were willing to place their trust in a woman for this historic first election.

Abderrahim’s candidacy for mayor was not without controversy. For example, Fuad Bouslama, a member of Nidaa Tounes, argued that a female mayor cannot attend national religious ceremonies at the national Ez-Zitouna Mosque due to the separation of genders at all Islamic religious facilities (Grewal & Cebul, 2018). The fact that this statement came from a representative of Nidaa Tounes highlights the intricacies of gender politics even within secular circles. Women who ran for municipal council seats did not face this kind of opposition, but a woman in an executive position—in the capital city at that—seems to have raised greater (or at least more public) concerns about the capacity of women to carry out all necessary duties of the office. Despite the obstacles, Abderrahim won the mayoral election and became mayor of Tunis on July 3, 2018, after defeating the Nidaa Tunis candidate by only four votes (out of a 60-member council).

As the first elected—rather than appointed—mayor of Tunis, Abderrahim has come up against unresolved tensions between local and national authorities. On September 29, 2018, the media leaked a video of Abderrahim asking Riad Mouakhar, the Minister of Local Affairs to grant her ‘minister of state’ status as the mayor of Tunis. Previously, when the mayor of Tunis was an appointed position, the mayor held a seat at the Council of Ministers in the capacity of Minister of State. Central government officials granted the title of Minister of State to the previous mayors of Tunis Mr. Mohamed Beji Ben Mami and Mr. Abbas Mohsen in 2010 and 2000, respectively.[7] Mouakhar argued that those privileges were canceled when the mayor’s office became an elected position and that he did not have the legal framework to authorize such titles. However, the legal channel or text that had previously legitimized this privilege is unclear; it might have been a customary tradition rather than a legal, constitutional one (Bouhlel, 2018). The uncertainty around whether the mayor of Tunis has the right to serve on the important and prestigious Council of Ministers under this new legal framework reflects unresolved debates about the power of locally elected officials and their relationship to central government bodies.

Still, Abderrahim is a strong advocate for decentralization and an increased role for municipal councils. “The law has articles that govern [decentralization’s] implementation in accordance with the constitution,” she says. “This includes granting municipal councils executive privileges to oversee the transition to decentralization gradually over the next eighteen years. I support the effort and continue to partner with various ministries to implement it” (Carnegie, 2018a). Along these lines, she is working to implement a municipal public health program to expand the hiring of local doctors and capacities of hospitals, bringing preventative medicine, reduced costs and extended hours to families living in poor neighborhoods. She is also working with the Ministry of Education to involve the municipality in designing school curricula. “We are working hard to exceed our traditional roles, as we feel we were elected to realize bigger hopes for the future of the country,” she says (Carnegie, 2018a). Her other priorities include restoring the powers that municipal councils were supposed to have, including service provision. When the RCD-dominated councils were abolished and replaced with appointed representatives after the revolution, they could not effectively meet demands for service provision and Abderrahim aims to change that despite still limited financial resources. She has emphasized street cleaning and lighting, the creation of green spaces, and the development of investment programs to improve infrastructure. These programs are part of a strategy to make Tunis a major tourist destination, along with meeting citizen demands.

Women’s Representation in Tunisia

Although Abderrahim’s election is an historic victory for women’s representation, especially in executive positions, it is important to note that women’s representation in Tunisia is not new. Under authoritarianism, the state feminist programs of Bourghiba (1956–1987) and Ben Ali (1987–2011) gave women opportunities to participate in the political sphere in ways that women in other Arab countries did not have. Women obtained suffrage in 1957 and the right to run for office in 1959. In 1959, one woman, Radhia Haddad, was elected to parliament. The percentage of women in parliament increased from 4 percent in 1989 to 12 percent in 1999, with 20 percent women’s representation on local councils. On the eve of the Arab Spring, women held 28 percent of seats in the Chamber of Deputies, 27 percent of seats on local councils and a number of women held ministerial posts (Benstead, 2018, p. 519).

After the Arab Spring, much of the attention has been paid to the national level, where women currently hold 68 of 217 seats (31.3 percent) in parliament, the Majlis Nuwwāb ash-Shaʿb (IPU, 2019). However, women are making major inroads at the local level. After the first municipal elections in 2018, female candidates were able to secure 47 percent of local council positions (UN Women, 2018). Unlike municipal council elections, Tunisia’s mayoral races lack gender quotas. Women still won an impressive number of mayoral races in 2018, about one-fifth, but the disparity between women’s representation on municipal councils versus mayoral offices demonstrates the importance of quotas for achieving higher levels of representation (Yerkes & McKeown, 2018). Abderrahim has stated that the discrepancy between women’s representation on municipal councils versus mayoral offices (47 percent to 19.5 percent) is a result of the “lack of trust by the elites in the capacity of women” (Cargnelutti, 2018). According to Abderrahim, negative reactions to her election is proof of the “masculine mentality of the people,” and she considers herself “as a symbol for all Tunisian women” in this fight for change (Cargnelutti, 2018).

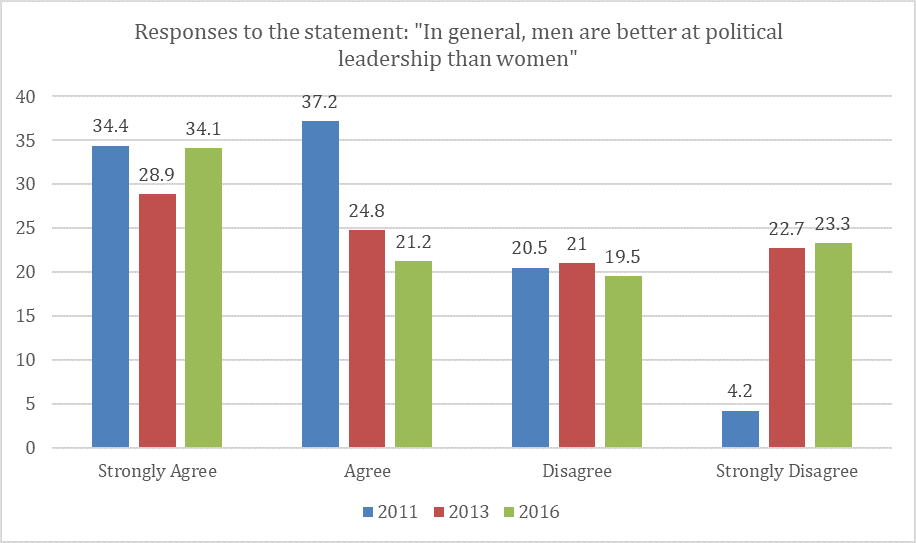

Cultural change does appear to be taking place as women’s representation has increased, if only to a limited degree. The regional public opinion survey, the Arab Barometer, has included a question about women’s fitness for political office in three waves of survey-collection in Tunisia: 2011, 2013, and 2016. Figure 1 below shows responses to this question and demonstrates that since the first wave, support for female politicians was higher in 2013 and in 2016 compared to 2011. The first wave was conducted from September 30– October 11, 2011, just over nine-months after the ouster of Ben Ali and just prior to the Constituent Assembly elections on October 23, 2011 where half of the candidates were women. Women ultimately won 24 percent of seats in the National Constituent Assembly, convened to draft the new Constitution. The second wave took place from February 3–25, 2013, during deliberations over the 2014 constitution. Finally, the last wave, February 13–March 3, 2016 took place after women had won approximately one-third of the seats in the national parliament.

Figure 3: Responses from three waves of the Arab Barometer in Tunisia. Question asks respondents to state their level of agreement with the statement “In general, men are better at political leadership than women” (Waves II, III, and IV of the Arab Barometer).

The results show that positive attitudes for women in politics was highest overall in 2013, dropping slightly in 2016. In 2013, 43.7 percent of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed that men make better political leaders than women; in 2016, that number was 42.8. The most striking change is in the column furthest to the right, tallying the respondents that strongly disagreed with the statement, thereby expressing the most support for female politicians. In 2011, only 4.2 percent of respondents strongly disagreed. In 2013, that number jumped up to 22.7 percent, and increased slightly to 23.3 percent. This is a nearly 20 percentage point increase from 2011, reflecting a major shift in attitudes.

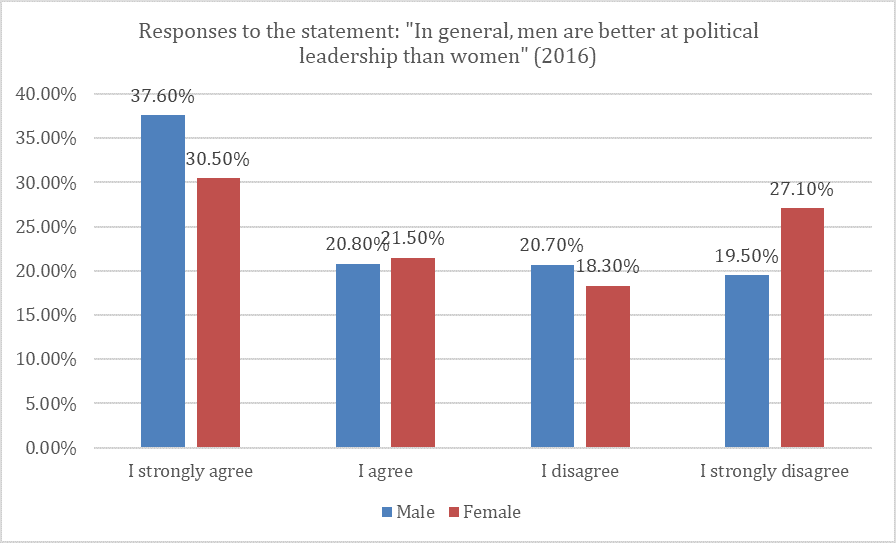

Unsurprisingly, women are more receptive to female politicians than men (as shown in Figure 4). Yet, there are still more women who strongly believe that men are better at political leadership (30.5 percent) than there are women who strongly disagree with this idea (27.1 percent). A slight majority of women agree or strongly agree that men make political leaders (52 percent), while 58.4 percent of men do.

Figure 4: Responses from the 2016 wave of the Arab Barometer in Tunisia, by gender. Question asks respondents to state their level of agreement with the statement “In general, men are better at political leadership than women” (Wave IV of the Arab Barometer).

Although the majority of (male and female) respondents still believe that men are better at political leadership than women, the contingent of those that strongly reject that idea has grown dramatically since 2011. Given the wins women had at the local level in 2018, it will be interesting to see whether future surveys reflect even larger shifts in public opinion, especially given that the local level is perhaps more visible to the average respondent than the dynamics of national politics.

Still, bottom-up cultural change may not matter much to alter the pattern of low levels of women’s representation in mayor positions if the attitudes of political elites remain unchanged, given that these elections occur indirectly. Of course, higher levels of women’s representation on these local councils may make it more likely for a woman candidate for mayor to gain a majority of votes; however, without direct elections and gender quotas, it is unlikely that we will see many more female mayors come to power under the current institutional framework.

Women in executive leadership positions are especially important because they can bring more women into positions of power, either directly through their own actions or indirectly by shaping attitudes and serving as an inspiration. In Tunis, Abderrahim is working to elevate women in local government. Of fifteen committees on the municipal council, eleven are headed by women. According to Abderrahim, “We must empower women through actions — for example, by making job offers or calls for candidature,” illustrating the fact that she recognizes that her position gives her direct power to bring more women into the fold (Crowe, 2018). Seeing a larger role for women in government may change attitudes in such a way that it opens the door for more women to run for office—and win.

Research shows that more female representation may lead to better service provision and increased political participation of women at the citizen-level. Benstead (forthcoming) found that higher levels of female representation on Tunisia’s municipal councils “improves service and allocation responsiveness to women, in the form of increased interactions between women and local councilors, which fosters their ability to request help with personal or community problems or to express an opinion” (p. 8). Her survey work showed that men are thirteen-percentage points more likely to know a local councilor, and six-percentage points more likely to contact local officials overall. This is, in part, because men are equally able to contact male and female councilors, while women are less able to contact male councilors. Thus, higher levels of female representation “reduce gender gaps in access to services by empowering women, not by excluding men” (Benstead, forthcoming, p. 37).

More women in office increases opportunities for women to express their concerns and have their voices heard, increasing representation for all. The ability of citizens to contact representatives, to voice their grievances and to make requests is a crucial aspect of participatory local governance. Given that women may be more comfortable contacting female representatives, and more female representatives are being elected, perhaps local politics becomes another important avenue for women’s agency and interest articulation, or at least another important avenue beyond the regional or national level. This might prove to be especially important in marginalized regions where the need for services and greater spatial equality and political representation is greatest.

Conclusion

The inclusion of women in local governance is part of a broader push for female participation in all levels of politics in order to bring new voices to the table and ensure equal representation. Women in local government may have more opportunities to make change than women in national politics, especially when decentralization processes grant power to local governing bodies and bureaucrats. The International Union of Local Authorities (IULA) adopted the Worldwide Declaration on Women in Local Government (1998), which argues that “local government is in a unique position to contribute to the global struggle for gender equality [...]The systematic integration of women augments the democratic basis, the efficiency and the quality of the activities of local government” (Paragraphs 10 and 11, as cited in UCLG, 2012). The Charter for Women’s Right to the City emphasizes equal access to decision making processes as a way to achieve gender equality, calling for “the institutionalization of women’s machineries as a structure of local city government with their own budget, thus guaranteeing gender mainstreaming in all areas of municipal action and in local governments public policies, programs and plans” (Habitat International Coalition, 2005).

Municipal councils in Tunisia are responsible for developing, approving, and implementing their own annual budgets. With this new power and with more women on municipal councils, there is an opportunity for gender mainstreaming, i.e. centering gender perspectives in “policy development, research, advocacy/ dialogue, legislation, resource allocation, and planning, implementation and monitoring of programmes and projects” (UN Women, n.d.). Yet there is no guarantee that women will be able to effectively represent women’s interests as male majorities may marginalize new female representatives (Schwindt-Bayer, 2010). Abderrahim has pointed to the distrust of women amongst political elites as a major barrier in Tunisia; however, as we have shown, cultural attitudes may be shifting as female representation has increased.

Although the newly elected women in Tunisia’s local government will more than likely face many barriers, maintaining representative political offices is a principal means through which local bureaucracies might achieve responsive service delivery. Scholars have established a link between passive representation (demographic representation) and active representation (policy adoption and implementation) whereby public organizations that are demographically representative of their clientele become more inclined to implement policies and deliver services in ways that are consistent with the interests of those clients (Meier, 1993; Keiser et al., 2002; Sowa & Selden, 2003; Meier & Nicholson-Crotty, 2006; Wilkins & Keiser, 2006). More women in office may allow for better representation of women’s interests, either because female constituents may be more likely to contact their representatives or because female representatives—as a result of their experience as women—better understand the issues women face and care about.

Women may have different interests from men when it comes to public services and certain issues may be more important to them. While men have an obligation (real or imagined) to generate income for the family, women are often responsible for providing for the family in other ways: feeding them, educating children, keeping family members in good health, and caring for them when they are sick. This dynamic in which men primarily engage in “productive” labor and women are responsible for care work holds not just in Tunisia, but in many parts of the world, including the industrialized West, although it is on the decline. Public services—especially healthcare, education, childcare, clean water, and sanitation services—can ease the burdens of care work. In its 2016 report “Transforming Economies, Realizing Rights,” UN Women explains that “where basic social services are lacking and care needs are great, women and girls’ unpaid workloads increase. Conversely, investment in basic services can reduce the demands of unpaid care and domestic work on women, freeing up time for other activities” (p. 157). Female politicians and bureaucrats may be more likely to understand and respond to these needs, actively representing women. Through her efforts to institute a municipal public health program and her work with the Ministry of Education to involve the municipality in the design of school curricula, Abderrahim may help to reduce the demands of care work for women in Tunis, especially poor women who shoulder much more of a burden without the aid of public resources.

Although the powers of municipal councils seem limited, the services they are responsible for have the potential to have a direct and meaningful impact on people’s lives. Local authorities are responsible for waste collection, road and pavement rehabilitation, street lighting, sewage systems, water and sanitation, and public spaces within their jurisdictions. Improving the city and people’s neighborhoods through the provision of these services is part of the “right to the city,” which includes the equitable distribution of quality public services to achieve welfare for all inhabitants. However, the right to the city involves more than the provision of services. Harvey (2008) extends the meaning of the right to the city to include democratic control over the process:

The right to the city is far more than the individual liberty to access urban resources: it is a right to change ourselves by changing the city. It is, moreover, a common rather than an individual right since this transformation inevitably depends upon the exercise of a collective power to reshape the processes of urbanization. The freedom to make and remake our cities and ourselves is […] one of the most precious yet most neglected of our human rights. (p. 23)

While a “collective power” is a worthy goal, feminist political theorists have raised challenges to a universalistic citizenship that ignores group differences. Young (1989) argues that “the ideal that the activities of citizenship express or create a general will that transcends the particular differences of group affiliation, situation, and interest has in practice excluded groups judged not capable of adopting that general point of view” (p. 251). Women may experience the city differently and have concerns that differ from those of men. For example, drawing on the experiences of women in London and Jerusalem, Fenster (2006) finds that “fear of use of public spaces, especially in the street, public transportation and urban parks is what prevents women from fulfilling their right to the city” (p. 224). Men are less likely to experience fear of public spaces, so unless women’s concerns are incorporated into the “exercise of collective power,” the right to the city will not be available to all.

In Cairo, women mobilized to combat sexual harassment and assault by mapping occurrences across the city; the resulting map is a stark visualization of women’s experience of the city. These incidents of sexual harassment constitute “everyday interactions” that may be reproduced by urban planning schemes (such as the design of public spaces and the accessibility of public transportation) if planners do not take women and their experiences into account (Abdelfattah, 2019). Equal participation requires “special rights that attend to group differences,” and institutional mechanisms for group representation (Young, 1989, p. 251). As Fenster (2006) argues, “the right to the gendered city means that the right to use and the right to participate must engage a serious discussion of patriarchal power relations” which “utopian” depictions of the right to the city often fail to acknowledge (p. 229).

If municipalities in Tunisia are able to take safety into consideration when developing plans for public spaces, lighting, and the rehabilitation of streets, they might increase access to these spaces for women. Abderrahim is committed to street cleaning and lighting, the creation of green spaces, and the development of investment programs to improve infrastructure in spite of limited resources. The provision of other public services, such as those that reduce the burden of care work, also allow for greater participation in public life. The incorporation of women into urban planning and participatory processes creates “a sense of belonging [which] is established by repeated fulfilment of the right to use” (Fenster, 2006, p. 222). Female citizens must be involved in deliberations over the development and implementation of these policies, as well as all public services that shape city life, if there is any chance of achieving the gendered right to the city.

Through decentralization, quotas for women on local councils, and granting more power to municipalities, Tunisia has extended the right to participation in the city. It is too early to say how successful Abderrahim and the other women elected to local offices will be in realizing the goals of decentralization, increased service provision, and greater representation of women’s interests. However, this large wave of democratically elected women offers the greatest chance that men and women in Tunisia have had at local representation since the 2011 revolution.

[1] The financial judiciary is a central government entity which is one of four bodies of the Supreme Judicial Council (Article 112 of the Tunisian constitution).

[2] The decentralization fund amounts to 1.45 billion TND, approximately 500 million USD (Kapitalis, 2019).

[3] The six constitutional committees, which reflected the priorities of the NCA were: 1) The preamble, basic principles, and constitutional review; 2) Rights and freedoms; 3) Legislative and executive powers, and relations between the powers; 4) Civil, administrative, financial, and constitutional justice; 5) Constitutional bodies to deal with media pluralism, financial regulation, politics and religion, and law enforcement and security; and 6) Local, regional, and municipal issues (Pickard, 2012).

[4] Tunisia’s youth quota requires that all lists must include at least one person between the ages of 18 and 35 within the top three slots on the list. After the top three slots, each set of six candidates must include one young person. Parties tended to place youth as far down on the list as possible–only about 36% of youth candidates were in the top two slots on the lists (Blackman, Clark, & Şaşmaz, 2018, p. 1).

[5] The vertical and horizontal parity arrangement that Tunisia employed in the NCA elections and the first parliamentary elections held for the municipal level, but only for local councils. Thus, parties were required to alternate female candidates on their lists (vertical parity) and parties running in an even number of municipalities must have an equal number of male- and female-headed lists (horizontal parity). Parties running in an odd number of municipalities could have one additional male- or female- headed list (Clark, Şaşmaz, & Blackman, 2018, p. 1).

[6] In a survey of candidates, researchers found that 36 percent of male candidates on Ennahda lists for the 2018 municipal election had previous experience in government, while only 12 percent of female candidates did (Clark, Şaşmaz, & Blackman, 2018, p. 6). Compared to other parties, Ennahda had the largest gender gap between male and female candidates with regard to political experience. Nidaa Tounes lists had the smallest gender gap: 33 percent of male candidates had experience, compared with 20 percent of female candidates. While the large percentage of female candidates without political experience on Ennahda lists might mean that women are only “fillers,” the researchers made the case that female candidates may have “higher raw potential than male candidates” given their higher levels of education and greater enthusiasm for a future career in politics (Clark, Şaşmaz, & Blackman, 2018, p. 9).

[7] It is worth noting that the title was not granted to Seifallah Lasram who was the mayor of Tunis from 2011 to 2018. During this time period, the RCD-dominated municipal councils were abolished and replaced by appointed representatives. The new role for municipal governments remained uncertain until after the passage of the Code on Local Authorities in 2018. This is likely the reason that Lasram did not receive this title (Bouhlel, 2018).

References:

Abdelfattah, L. (2019). Deconstructing the trajectories of gendered mobility in Cairo: lessons for urban policy. Unpublished master’s thesis. Politecnico Di Milano: School of Architecture, Urban Planning and Construction Engineering, Milan, Italy

Abderrahim, T. (2017). Tunisia’s decentralization process at a crossroads. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved from https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/71135

Arab Barometer. (2011). Wave II. Retrieved from https://www.arabbarometer.org/waves/arab-barometer-wave-ii

Arab Barometer. (2014). Wave III. Retrieved from https://www.arabbarometer.org/waves/arab-barometer-wave-iii

Arab Barometer. (2016). Wave IV. Retrieved from https://www.arabbarometer.org/waves/arab-barometer-wave-iv

Beinin, J. (2015). Workers and thieves: Labor movements and popular uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt. Stanford: Stanford University Press

Benstead, L. J. (2019). Tunisia: Changing patterns of women’s representation. In S. Franceschet, M. Krook, & N. Tan (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of women’s political rights (517-530). London: Palgrave Macmillan

Benstead, L. J. (forthcoming 2019). Do female local councilors improve women’s representation? Journal of Middle East and Africa. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/25602636/Do_Female_Local_Councilors_Improve_Women_s_Representation

Blackman, A., Clark, J., & Şaşmaz, A. (2018). Generational divide in Tunisia’s 2018 municipal elections: Are youth candidates different? Democracy International. Retrieved from http://democracyinternational.com/media/LECS_Policy%20Brief_Youth.pdf

Boughzala, M., & Hamdi, M. T. (2014). Promoting inclusive growth in Arab countries: Rural and regional development and inequality in Tunisia. Global Economy and Development, Brookings Institution, Working paper 71. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Arab-EconPaper5Boughzala-v3.pdf

Bouhlel, C. (2018). To what extent is Souad Abderrahim wrong? [Translated] The New Jorter. Retrieved from https://newjorter.com/2018/09/30/is-souad-wrong/

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. (2018). [Infographics displaying the results of Tunisia’s elections]. Results from Tunisia’s 2018 municipal elections: Resource page. Retrieved from https://carnegieendowment.org/2018/08/15/results-from-tunisia-s-2018-municipal-elections-pub-77044

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. (2018a). Interview with Mayor of Tunis Souad Abderrahim. Retrieved from https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/78183

Cargnelutti, F. (2018). Tunisia’s slow but steady march towards gender equality. Equal Times. Retrieved from https://www.equaltimes.org/tunisia-s-slow-but-steady-march#.XQJgiFxKi1s

Charrad, M. M., & Zarrugh, A. (2014). Equal or complementary? Women in the new Tunisian constitution after the Arab Spring. The Journal of North African Studies, 19(2), 230-243

Clark, J., Dalmasso, E., & Lust, E. (2017). Not the only game in town: Local-level representation in transitions. The Program of Governance and Local Development at Gothenburg, Working Paper No. 15. Retrieved from http://gld.gu.se/media/1325/lust-dalmasso-clark-final.pdf

Clark, J., Şaşmaz, A., & Blackman, A. (2018). List fillers or future leaders? Female candidates in Tunisia’s 2018 municipal elections. Democracy International. Retrieved from http://democracyinternational.com/media/Policy%20Brief_Gender.pdf

Crowe, P. (2018). Tunisians wonder what their first female mayor will do for women. PRI. Retrieved from https://www.pri.org/stories/2018-10-26/tunisians-wonder-what-their-first-female-mayor-will-do-women

de Silva de Alwis, R., Mnasri, A., & Ward, E. (2017). Women and the making of the Tunisian constitution. Berkeley Journal of International Law (BJIL), 35, 90. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=2983803

Fenster, T. (2005). The right to the gendered city: Different formations of belonging in everyday life. Journal of Gender Studies, 14(3), 217-231. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/09589230500264109

Feuer, S. (2018). Supporting Tunisia’s moves toward local governance. The Washington Institute for Near East Policy: Policy Analysis. Retrieved from https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/supporting-tunisias-moves-toward-local-governance

Grewal, S. & Cebul, M. (2018). What does Tunis think of its first female mayor? The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved from https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/76810

Habitat International Coalition. (2005). Proposal for a charter for women’s right to the city. Retrieved from www.hic-net.org/articles.php?pid=1685

Harvey, D. (2008). The right to the city. New Left Review, 2(53): 23-40. Retrieved from https://newleftreview.org/issues/II53/articles/david-harvey-the-right-to-the-city

Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU). (2019). Women in national parliaments. Retrieved from http://archive.ipu.org/wmn-e/classif.htm

Kapitalis. (2019). al-Aʿlān ʿan ḥizma min al-qararāt tahimma al-shaʾn al-baladī wa-l-maḥalī. Retrieved from http://www.kapitalis.com/anbaa-tounes/2019/03/26/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%B9%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%86-%D8%B9%D9%86-%D8%AD%D8%B2%D9%85%D8%A9-%D9%85%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%82%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D8%AA%D9%87%D9%85%D9%91-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B4%D8%A3%D9%86/

Keiser, L. R., Wilkins, V. M., Meier, K. J., & Holland, C. A. (2002). Lipstick and logarithms: Gender, institutional context, and representative bureaucracy. American Political Science Review, 96(3), 553-564. Retrieved from http://orca.cf.ac.uk/40328/1/Kaiser%202002.pdf

Litvak, J., Ahmad, J., & Bird, R. (1998). Rethinking decentralization in developing countries. The World Bank. Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/938101468764361146/pdf/multi-page.pdf

Meier, G. M. (1993). The new political economy and policy reform. Presented at a DSA conference. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3380050404

Meier, K. J., & Nicholoson-Crotty, J. (2006). Gender, representative bureaucracy, and law enforcement: The case of sexual assault. Public Administration Review, 66(6), 850-860. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/4096602

National Democratic Institute (NDI). (2011). Final report on the Tunisian National Constituent Assembly Elections. NDI: Mission d’Observation Internationale Tunisie. Retrieved from https://www.ndi.org/sites/default/files/tunisia-final-election-report-021712_v2.pdf

National Institute of Statistics. (2012). Measuring poverty, inequalities and polarization in Tunisia: 2000-2010. Statistiques Tunisie. Retrieved from https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Project-and-Operations/Measuring_Poverty_Inequalities_and_Polarization_in_Tunisia_2000-2010.PDF

Ordu, A. U., Ncube, M., Kolster, J., & Vencatachellum, D. J. M. (2011). The revolution in Tunisia: economic challenges and prospects. AfDB, Economic Brief. Retrieved from https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/North%20Africa

%20Quaterly%20Analytical%20Anglais%20ok_North%20Africa%20Quaterly%20Analytical.pdf

Pickard, D. (2012). The current status of constitution making in Tunisia. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved from https://carnegieendowment.org/2012/04/19/current-status-of-constitution-making-in-tunisia-pub-47908

Sadiki, L. (2019). Regional development in Tunisia: The consequences of multiple marginalization. Brookings Doha Center Publications. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/research/regional-development-in-tunisia-the-consequences-of-multiple-marginalization/

Şaşmaz, A. (2018). Who really won Tunisia’s first democratic local elections? The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2018/06/01/who-really-won-tunisias-first-democratic-local-elections/?utm_term=.b5a975175357

Schwindt-Bayer, L. A. (2010). Political power and women’s representation in Latin America. New York: Oxford University Press

Sowa, J. E., & Selden, S. C. (2003). Administrative discretion and active representation: An expansion of the theory of representative bureaucracy. Public Administration Review. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6210.00333

Tunisian Code on Local Authorities. (2018). Retrieved from http://www.collectiviteslocales.gov.tn/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/cadre-juridique-lois-2018.pdf

Tunisia’s Constitution of 2014. Retrieved from https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Tunisia_2014.pdf

United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG). (2007). Tunisian republic. Retrieved from https://www.gold.uclg.org/sites/default/files/Tunisia_0.pdf

United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG). (2012). Women in local decision making: Leading global change. UCLG Briefing Note: Contributions to the High Level Panel, London. Retrieved from https://www.uclg.org/sites/default/files/LG%20brief%20on%20Women%20in%20local%20Decision%20making-Octobre%202012_FINAL_R.pdf

UN Women. (2018). Historic leap in Tunisia: Women make up 47 percent of local government. Retrieved from: http://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2018/8/feature-tunisian-women-in-local-elections

UN Women. (2016). Progress of the world’s women 2015-2016: Transforming economies, realizing rights. Retrieved from http://progress.unwomen.org/en/2015/pdf/UNW_progressreport.pdf

UN Women. (n.d.). Gender mainstreaming. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/womenwatch/osagi/gendermainstreaming.htm

UN Women. (n.d.). Men’s health enhamainstreaming. Retrieved from https://hlthask.com/online-pharmacy-that-accepts-bitcoin/

Walles, J. (2018). Risk or opportunity? Diwan: Middle East Insights from Carnegie. Retrieved from https://carnegie-mec.org/diwan/75979

Wampler, P., & McNulty, S. L. (2011). Does participatory governance matter? Exploring the nature and impact of participatory reforms. Comparative Urban Studies Project, Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars. Retrieved from https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/CUSP_110108_Participatory%20Gov.pdf

Wilkins, V. M., Keiser, L. R. (2006). Linking passive and active representation by gender: The case of child support agencies. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 16(1), 87-102. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mui023

Yerkes, S., & McKeown, S. (2018). What Tunisia can teach the United States about women’s equality. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved from https://carnegieendowment.org/2018/11/30/what-tunisia-can-teach-united-states-about-women-s-equality-pub-77850

Young, I. M. (1989). Polity and group difference: A critique of the ideal of universal citizenship. Ethics, 99(2), 250-274. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/2381434

Comments