Egypt’s New Cities: Neither Just nor Efficient

Introduction

Egypt’s New Urban Communities (NUCs) have been hailed by the Egyptian government as the solution to all that ails urban Egypt. Since the 1970s, when they were first planned as a means to disperse the growing urban population more evenly across Egypt’s vacant desert lands, state-planned NUCs have been popping up all over the country.

Three main policies have long been dominant in the Egyptian context: the real estate and construction sectors will boost economic growth, land sales will finance the budget deficit, and building new houses will solve the housing crisis. The end result of these three policies is the establishment of new cities in the desert. These institutional preferences and policies surrounding land management, real estate management, and housing construction have hardly been challenged for their effectiveness, efficacy, or efficiency.

The government agency responsible for the new cities – the New Urban Communities Authority (NUCA) – is planning to invest billions of pounds in the proposed new Egyptian administrative capital, and it continues to invest billions in its new cities across the country. Hence, raising questions about the real benefits of this new city is an imperative and timely matter. While billions are spent on the new cities, Egypt’s older cities continue to suffer from insufficient public resources and deteriorated services. This has increased the inequality between existing cities which house millions and the new urban areas that have been repeatedly described in the media as “ghost cities” (DNE, 2012).1 Furthermore, despite the early establishment of some new cities (beginning in 1977) which were supposed to provide affordable housing to lower-income groups, informal areas in older urban areas have continued to grow as the poor find such housing better at meeting their needs than relocating to the NUCs in the desert.

This brief aims to answer questions about the new cities success in achieving their goals and their supposed contributions to the country, as a whole. Thus, it is imperative to conduct a cost/benefit analysis of the new cities continued expansion and to explore how these policies may burden the existing cities and urban areas, while serving less of the population. The brief starts by reviewing the history of new cities as an idea and then a national policy. The brief then delves into the stated goals of the new cities policy and compares this to their performance since their inception. Finally, the brief presents an analysis of the drawbacks of the policy, problematizing many widespread myths about NUCA’s contributions to the nation.

Historical Overview of Egypt’s New Cities

Although the idea of building “satellite cities in the desert” had been proposed since the 1950s (e.g. in Cairo’s 1956 unapproved master-plan, and later in Cairo’s 1970 approved master-plan), the real push towards the desert occurred after the 1973 war and the dawn of the “Infitah” [open-door] policy (El-Kadi, 1992). In Sadat’s 1974 “Waraqat Uktubar” (October Working Paper), he spoke of developing Egypt’s “strategic vacuums” to develop a new map of Egypt (Sims, 2014). The 1974 paper highlighted the social purpose of desert expansion and yet NUCA has consistently deviated from this social role, embracing the role of a real estate developer instead.

Planning for the new cities began shortly thereafter and by 1977 the 10th of Ramadan City – the first city to be labeled as one of Egypt’s NUCs – was underway. The city was to have an independent economic base fueled by industrial factories, government-built housing and subsidized land. Its initial target population was 500,000 – mostly workers – who would be attracted by manufacturing jobs (Sims, 2014).

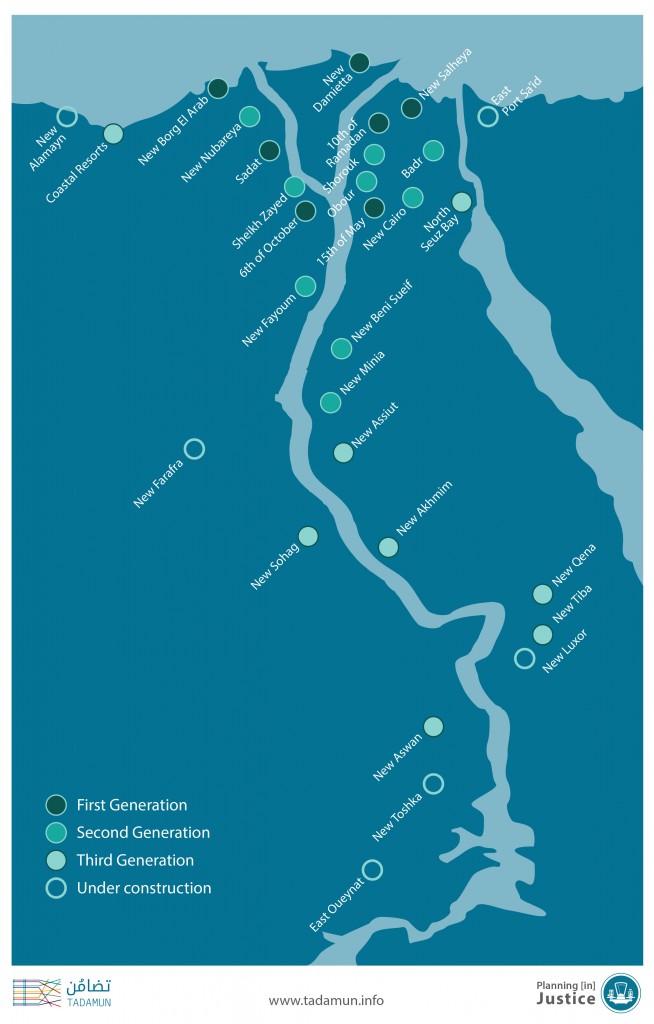

By that time, construction of these new desert cities was repeatedly articulated as a national policy, and thus NUCA was founded in 1979 by law 59/1979 as the official governmental authority in charge of overseeing their development. Between 1977 and 1982 seven “first generation” new cities were planned, consisting primarily of free-standing cities with independent economic bases.2 But one notable exception was 15th of May city. Unlike most other new cities, 15th of May City did not have an independent economic base, but rather was designed as a satellite city extending just beyond Cairo’s natural urban growth. The government built numerous social housing blocks to catalyze the new city’s absorption of Cairo’s growing population.

In 1982, the French organization “Institut d’Aménagement et d’Urbanisme de la Région Ile de France” (IAURIF) submitted a study commissioned by the General Organization for Physical Planning (GOPP) to support the development of a new Cairo master-plan and USAID also submitted a National Urban Policy study that same year. The USAID study suggested that resources should be directed towards improving existing urban agglomerations – particularly in Upper Egypt and the Suez Canal regions – a recommendation that dealt an indirect blow to the state’s new cities policy (Sims, 2014). The study by IAURIF critiqued the policy more directly, but argued that instead of setting up free-standing new cities, national resources should be redirected towards establishing satellite towns around existing cities, to absorb the burgeoning urban populations, while allowing residents to continue to benefit from the existing cities’ economic advantages.

While the Egyptian government was not pleased by the USAID study (Sims, 2014), the IAURIF study and recommendations were formally approved by then-President Husni Mubārak in 19833. Thus, mimicking the approach of 15th of May city, the state launched a series of nine “second generation cities” in 1986 consisting almost entirely of such satellite towns and “twin cities” which were to be built as sister towns or twins to provincial cities.4 In 2000, seven “third generation” cities were launched and also consisted entirely of provincial sister towns.5 In total, there are currently 23 New Urban Communities (NUCs) across Egypt, and another five are underway, bringing them to a total of 28 NUCs.

In 2008, the Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA) published a “Strategic Urban Development Master-Plan Study for Sustainable Development of the Greater Cairo Region.” The study outlined three possible scenarios for future growth of the Greater Cairo Region (GCR) and proposed the third scenario as “the most preferable future growth pattern”. That scenario was based on controlling and limiting future urbanization and population growth and directing people towards the new urban communities on Cairo’s periphery. Thus, this study reinforced the existing policy regarding the planned development of Egypt’s new cities. There are eight cities within the borders of the GCR: 6th of October, 10th of Ramadan, 15th of May, Badr, Ubur, Shaikh Zayid, Al-Shuruk, and New Cairo. Egypt’s New Administrative Capital is one of the NUCs currently “in development.“

New Cities in Theory: The Goals of Egypt’s New Urban Communities

The goal of Egypt’s NUCs, according to the decree founding NUCA, is to create new “civilized” centers, redistribute inhabitants far from the narrow strip of the Nile valley, develop new attractive areas beyond the existing cities and villages, extend urban spines to the desert and remote areas, and limit urban encroachment on agricultural land; essentially meaning that the raison d’etre of the NUCs is to attract people to these new cities.

A sub-goal of the NUCs is to provide shelter for lower-income groups, as a way to create an alternative to informal areas (Sims, 2014). NUCA’s internal real estate regulations state that part of its vision is to provide decent and adequate housing for every Egyptian citizen. Its mission includes fulfilling the housing needs of lower-income families, which NUCA estimates to be 1.5 million housing units (NUCA, 2015), though it is not clear how they arrived at this number. Furthermore, their regulations stipulate that the committee which sets the purchase price for land should consider these income differences when conducting their work. El-Sayed comments that the 1979 decree for NUCA’s establishment decree states that the Authority is responsible for implementing the state’s social responsibilities and thus must always consider the large base of needy people and thereby provide lower- and middle-income housing for them (2015).

Interestingly, NUCA’s mandate also includes putting in place the necessary plans to upgrade the ashwa’eyat by re-planning them, extending utilities to them, and provide shelter for those among them who are to be relocated (NUCA, 2015). Furthermore, the most recent social housing law (Law No.33/2014) states that the national social housing program is based on providing affordable housing units in “areas identified by the Ministry of Housing in the governorates and in the New Urban Communities” as well as providing land plots for middle-income families in the NUCs. Thus, in theory, NUCA’s mandate seems to endorse, at least partially, the “social function of property”. But has it applied this in practice?

The following section explores whether or not the creation of these 28 new cities has been an effective vehicle to achieve NUCAs foundational principles and objectives.

New Cities in Reality: Have They Achieved their Goals?

Attracting Residents

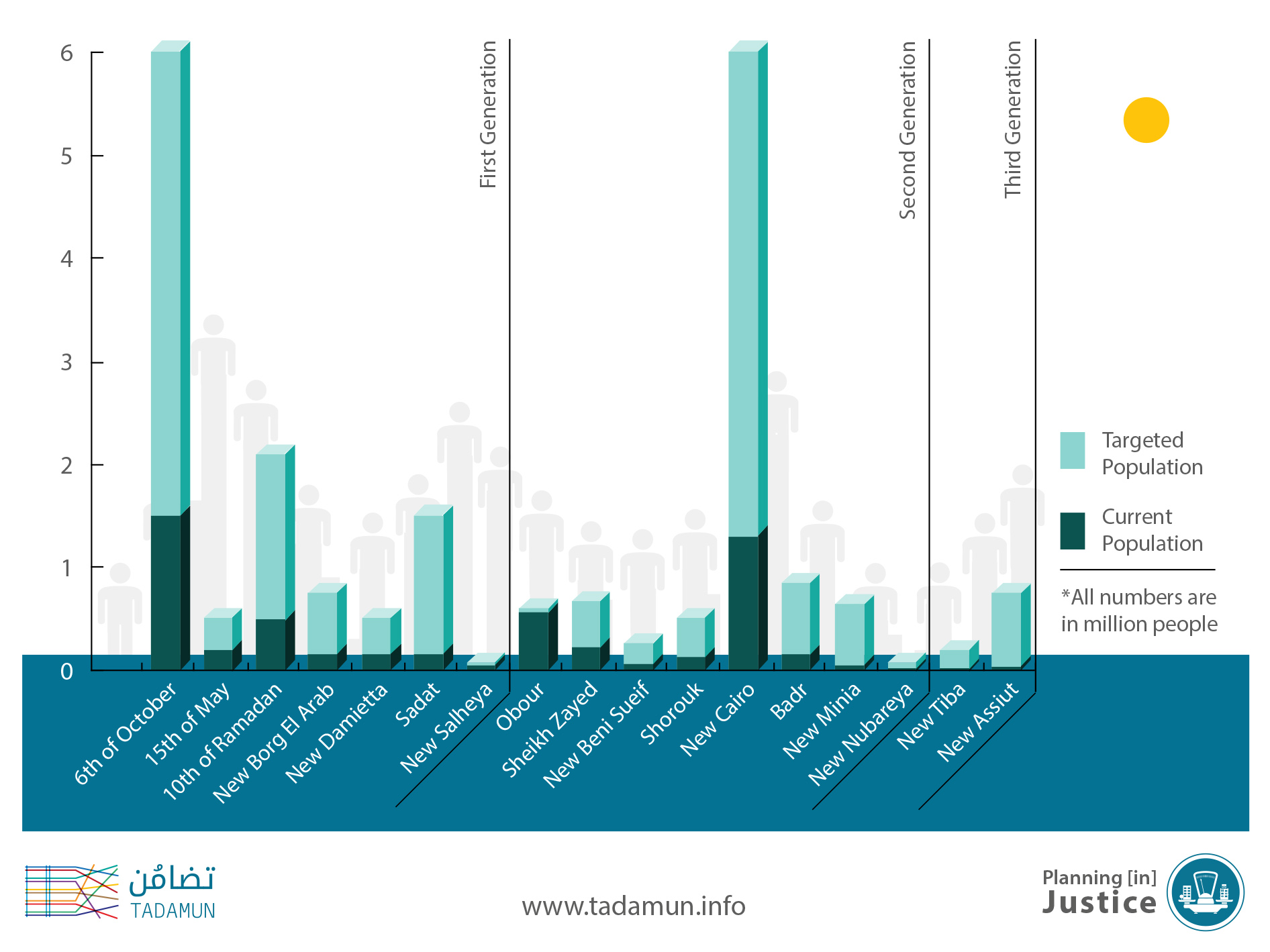

The NUCs’ main goal is to draw people away from the narrow Nile valley and disperse them more evenly across Egypt’s vacant lands. Towards this end, each NUC has a defined target population and a target year to realize that goal.6 The NUCs within the GCR have overall larger target populations, ranging between half a million to six million, while most of the provincial NUCs have relatively smaller targets.

Although many of the target populations are listed on the NUCA website, the target years are almost never listed. Interestingly, the population sizes listed by CAPMAS’s 2013 estimates are drastically different from NUCA’s 2015 estimates. In reality, the CAPMAS estimates are based on projections from the 2006 census and past population growth rates and thus are potentially underestimated since they would not account for the surge in families moving to new cities during the past three to four years. On the other hand, NUCA estimates include in their count all vacant homes/plots that have been sold but remain uninhabited and thus their estimates are probably too generous. Due to the boom in real estate speculation, many Egyptians have purchased plots in new cities, freezing them for decades until the land prices increase, and then selling them at a healthy profit. Other families purchase plots for their children to use many years later when they eventually marry. Thus, it is inaccurate to consider all sold plots as part of the population count. A more realistic estimate is likely somewhere in between the two numbers. The chart below depicts seventeen of Egypt’s NUCs (those for which target and current population data is available), comparing their target population to their current population according to NUCA estimates (2015).

As one can see from the chart above, even if we use NUCA’s generous counts, not a single new urban community has reached its target population and the vast majority have not even surpassed the 50% mark. Their performance is far worse when utilizing the 2013 CAPMAS population estimates. According to CAPMAS estimates, the new cities’ success at meeting their target population is far lower and ranges from a low of 3% to a high of 27%. Admittedly, one must take into consideration that many of the targets have been increased over the years. For example, 10th of Ramadan’s initial target was 500,000 inhabitants, but NUCA increased it later to 2.1 million. This begs the question, if the target was half a million people in 1977, and until 2015 the city had failed to reach that original target, why was the target population increased to 2.1 million? In fact, if one applies the same rate of actual increase the city has experienced over the past 38 years, reaching the 2.1 million target population by the target year 2032 is impossible. Assuming the same growth rate between 1977-2015 and 2015-2032, the population would reach a maximum of 700,000 people by the target year.

Furthermore, the majority of NUCs have been established as satellite or twin towns, rather than independent entities. Thus, residents of many NUCs continue to commute to the nearby main city for work. Within the GCR, for example, despite the population increases witnessed in 6th of October, New Cairo, and Shaikh Zayid cities, Cairo itself has not experienced any relief from the daily traffic and crowds and its population density continues to increase (CAPMAS, 2015).

Despite the failure to meet any of its population targets, the state has been increasing the number of NUCs over the years and has even been expanding the total settlement area of individual NUCs. For example, 15th of May city was originally designed in 1978 to include 6,462 feddans, but then another 1,858 feddans were added to it in 1995, and yet another 3,913 feddans in 2009 (NUCA, 2015). These expansions occurred despite the fact that 15th of May, according to NUCA’s (2015) overestimated counts, has a current population of only 200,000 (40% of its target). Similarly, NUCA originally established New Tiba in 2000 with an area of 5,445 feddans but increased its size in 2014 by an additional 4,050 feddans even though NUCA (2015) estimates its current population at 19,000 people – or only 10% of its target population.

According to NUCA’s establishment decree (1979), NUCA is responsible for building the new cities, providing them with services such as schools and clinics, and connecting them to utility networks. Once such “basic amenities” are completed within a particular NUC, NUCA should then inform the cabinet of Ministries, which then decides when to deliver the NUC back to the local administration of the governorate wherein the NUC lies.7 Until this happens, NUCA is responsible for planning and funding the development of each new city, and its annual plan includes the projects budget which lists how much will be invested in each NUC for that financial year. The NUCA website states the amount of money that has been spent on each NUC since its establishment, divided into money spent on utilities, services, and housing. The data shows that certain NUCs have consistently received the highest funding, namely, New Assiut, New Tiba, and New Minia, which are among the five NUCs that received the most spending on services per capita, utilities per capita, and housing per capita since establishment.

However, that high level of spending does not seem to be linked to success in attracting residents to those new cities. Although New Assiut, New Minia, and New Tiba have received the highest allocated funds per capita since their establishment, they have target population achievement rates of only 4%, 6%, and 10% respectively. Admittedly, this argument is potentially weakened by the fact that New Assiut and New Tiba were established more recently in 2000, so it makes sense that they have lower population achievements. However, New Minia was established in 1986 and has achieved a smaller percentage of its target population than the more recently created New Tiba.

On the other hand, Al-Ubur city is the most successful NUC in terms of achieving its target population (92% achievement rate).8 Yet, compared to other NUCs, the city ranks 13th out of 17 NUCs in per capita share of spending on services, and 17th in per capita share of spending on utilities.

Success in reaching population targets seems similarly detached from per capita spending on housing. For example, the successful (92%) Al-Ubur city ranks 14th in per capita spending on housing, while the less successful (6%) New Minia ranks first in per capita spending on housing – keeping in mind that both cities were established around the same time, in 1982 and 1986 respectively.

These figures raise a number of questions. Have there been any studies by NUCA to understand why certain NUCs have been more successful than others at achieving their targets? If such studies have been conducted, they have certainly not been made publicly accessible. Are the target populations poorly estimated in some NUCs or are some NUCs more attractive than others due to other factors? Given that spending is clearly not linked to populating these communities, has NUCA analyzed the effectiveness of its spending and its spatial distribution? These are all questions for which NUCA has provided no answers.

Housing Lower-Income Groups

As mentioned above, one of NUCA’s core foundational objectives is to provide affordable housing to lower-income and middle-income families.

Towards this end, NUCA has been allocating units it has built to the Social Housing Project (SHP, lower-income families & youth), the National Housing Project (NHP, Mubarak’s 2005 presidential scheme which includes lower- and middle-income housing), the Iskan Al-Shabab and Iskan Al-Mustaqbal lower-income housing projects, and the Dar Masr middle income project.

According to the data on the NUCA website, they have constructed hundreds of thousands of housing units and allocated them to each of the abovementioned projects.

But do these new houses really reach NUCA’s targeted population with lower financial means? Are these units really affordable for poorer groups and is NUCA meeting its professed goal of social justice? Shawkat’s previous analysis and research has demonstrated that the units supposedly allocated for lower- and middle-income groups typically do not reach the poor (2014).

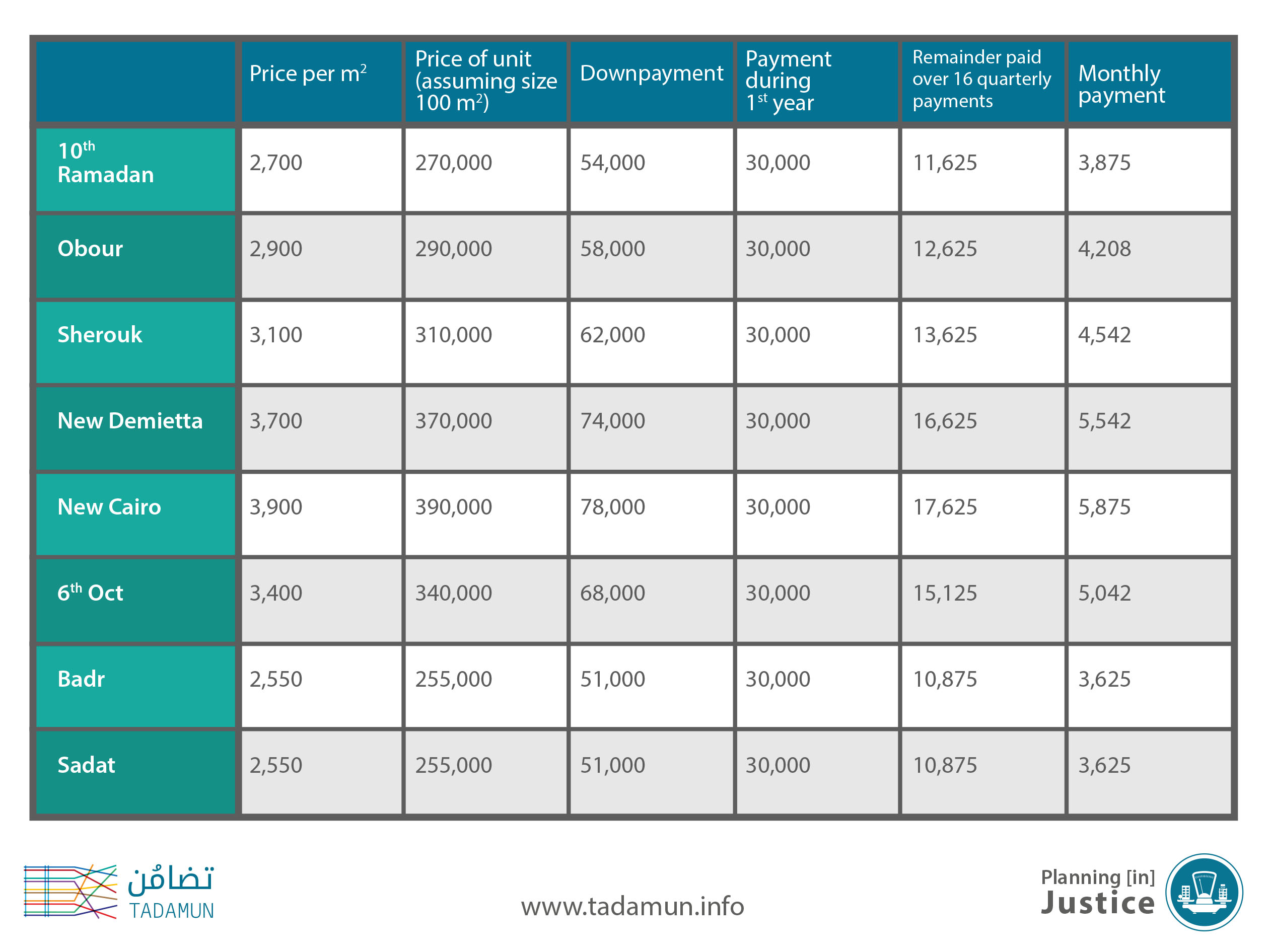

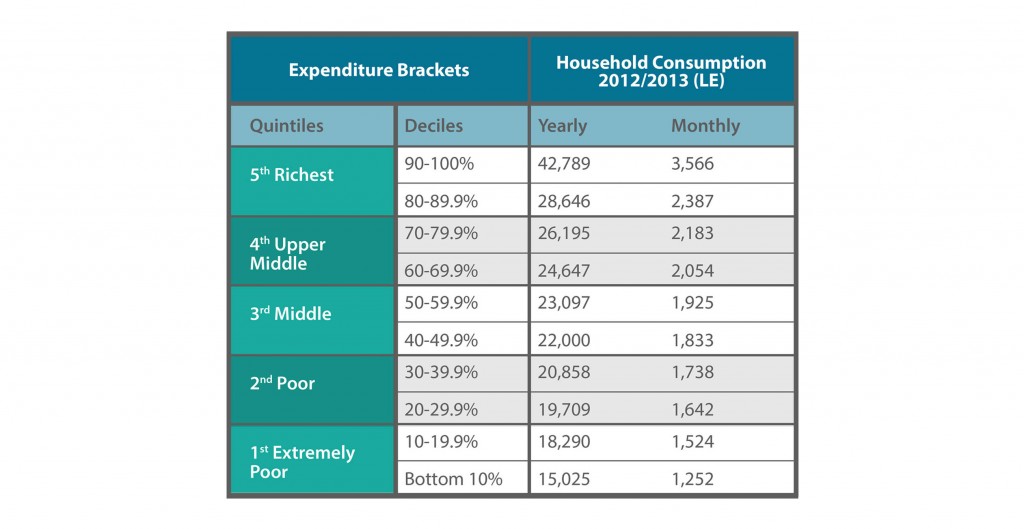

According to the NUCA website, they define lower-income groups – or in official terminology mahdudi al-dakhl, [those of limited income] – as families with an annual income of EGP 36,000 or less, and individuals with an annual income of EGP 27,000 or less (around USD 3350). The below table, adapted from Shawkat (2014), shows Egypt’s expenditure quintiles and deciles based on the the 2012/2013 Household Expenditure, Income, and Consumption Survey (HEICS) data. According to this data, households that spend EGP 36,000 annually fall among the richest 20% of the Egyptian population.

Furthermore, Egypt’s Mortgage Law, which is the funding mechanism for SHP units targeting limited-income groups (El-Sayed, 2015), excludes families whose annual incomes are less than EGP 23,000 (Abdelazim, 2014) – i.e. the poorest 50% of Egyptians according to HIECS 2012/2013.

Similarly, NUCA has announced thousands of units, ranging between 100m2 to 150m2, targeting middle-income families as part of the Dar Masr “middle-income” housing project. However, a brief examination of the prices of such units, and the monthly installment that applicants would have to pay, shows that these units are only affordable to upper-income groups. The table below shows the prices and payment schemes.

Source for prices: NUCA website here. Source for payment scheme: NUCA website here.

Note: All figures are in EGP; Calculations assume apartment is 100m2.

Based on the table above, households must pay monthly payments higher than EGP 3,500. According to HEICS (2012/2013) expenditure data, households spending more than EGP 2,387 fall among the richest 20% of households in Egypt.

The location of new units is just as important as the number of units constructed and their affordability for poorer people. The location of new cities on the periphery of existing cities makes them, by their very nature, inconvenient to anybody who has to commute back to the city for work. The majority of NUCs have been established as subsidiary cities and thus rely on the existing cities for jobs, entailing the need for most residents to commute on a daily basis. On the other hand, none of the NUCs are currently well-connected to effective public transportation networks, meaning that residents must own cars or rely on private transportation for their commute. This in itself makes the NUCs unattractive to those who can’t afford cars, which constitutes the majority of lower-income groups.

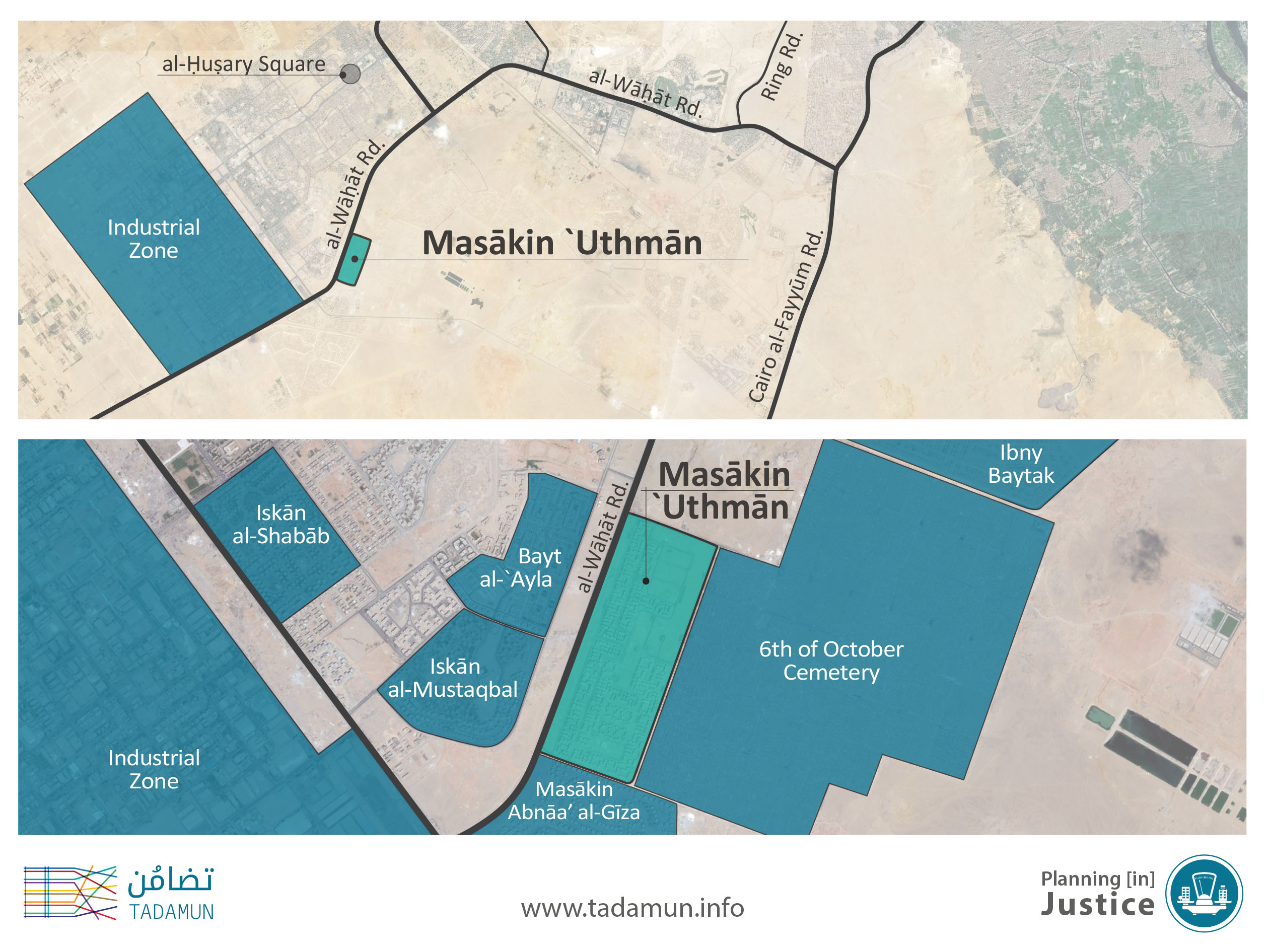

Furthermore, within many NUCs the social housing areas are located on the edges of the NUC and thus suffer from poorer services. For example, “Government Urbanism, New Cities” a short documentary film (IskanAlZil, 2013) shows how participants in one “Ibni Beitak” (Build Your Home) scheme were unable to move into their new homes due their location in a new underserviced area. In the words of one interviewee, the complete lack of services made the area unsafe and “uninhabitable.” Similarly, the “Awla Bil Ri’aya” (Most Care-Worthy) scheme in 6th of October city – known locally as Masakin Uthman and meant to house the poorest of the poor – is located to the south of the Al-Wahat highway, while all services are located to the north of that highway, as shown in the below image.

Many of the residents who were transferred there by the Informal Settlement Development Facility (ISDF) because their former homes were deemed structurally ‘unsafe,’ ended up returning to their original neighborhoods even though their homes had already been demolished. Despite huge problems of finding new housing, they preferred the old neighborhood to living in the destitute NUC. This does not mean that 6th of October city as a whole is underserviced, but that services are poorly distributed within the city. For example, the city of 1.5 million people has forty schools (NUCA, 2015), but they are all located on the other side of the highway, which children from Masakin Uthman have to cross on foot on a daily basis (TADAMUN, 2015).

Due to many of the above factors as well as others such as the high cost of living and the lack of transportation and services, many of the state-subsidized housing schemes suffer from high vacancy rates. Abouelmagd finds that one of the completed NHP schemes has only a 50% occupancy rate (2011). Unfortunately, the latest wide-scale data available on occupancy rates in the new cities is from the last national census in 2006, and thus does not say much about rates today. A recent news article states that occupancy rates in most new cities does not exceed 2%, although it is unclear how the author arrived at this number (Yahia, 2015).

The Drawbacks of New Cities

Relying on Land-Sales Creates an Unhealthy National Economy

As stated above, national policy in Egypt for decades has been to rely on the real estate and construction sectors as drivers of GDP growth.

According to the Central Bank of Egypt (CBE), the growth rate in the building/construction sector escalated from 0.7% in 1991/1992 to 11.2% in 1997/1998. During that same time, the growth rate in Egypt’s real estate sector escalated from and 1% in 1991/1992 to 6.2% in 1997/1998. However, an economic bubble had been in the making, and it burst in 2001/2002 due in part to the global recession in the early 2000s. Thus, the growth rate for the building/construction sector declined to -4.8% in 2002/2003, while the real estate sector fell to 0.1% that same year.

During the period between the early 1990s and early 2000s, Egypt’s informal areas continued to grow in size, despite the surge in the building/construction and real estate markets, and despite coercive measures taken by the government against unregulated urbanization. This highlights how ineffective this policy has been at solving the housing crisis among lower-income groups.

Despite the burst of the real estate bubble and the decline of the sector’s growth, the government tried again to jump start economic growth on the back of the construction and real estate sectors. Thus, according to CBE data, the in 2007/2008 the booming construction and real estate sectors were responsible for the major portion of the nation’s high growth rate. In 2007/2008, the real growth rate of the building/construction sector reached 15%, and then fell to only 5.9% in 2012/2013. On the other hand, the growth rate of the real estate sector rose to only 3.7% in 2007/2008, and continued to rise until it reached 5.6% in 2012/2013.

Despite the boom-bust growth in the building/construction and real estate sectors, the government insisted on investing in these sectors as the main drivers of its economic growth strategy. The 2014/2015 national plan tended to depend on these sectors as well to generate quick growth, the government planned for the building/construction sector to have a growth rate of 6.3%, and the real estate sector to have one of 5.6% which is the highest among all economic sectors. Similarly, in the 2015/2016 national plan the government planned for the building/construction sector to have a growth rate of 8.1% and for the real estate sector to have one of 6.4%.

The philosophy behind this approach is capitalizing on Egypt’s main abundant resource – land – as a means to finance the budget deficit and boost public revenues. Instead, the 2015/2016 national public budget shows that NUCA will only contribute an estimated EGP 8 billion to government coffers, which amounts to less than 1% of public expenditure.9 In the past several years, NUCA’s contribution to public expenditure has been even less according to the national budget in previous years.

It is also important to note that in the past NUCA used to be obliged to pay part of its surplus towards the Social Housing Fund according to Decree no.33/2014. This decree was modified in 2015 removing that obligation from the decree.

New Cities are Costing Too Much and Generating Too Little Revenue

The main channel for investing in land and new urban communities is NUCA. NUCA is an economic authority that is responsible for implementing and managing all projects, as well as providing services and administrative oversight in new cities.

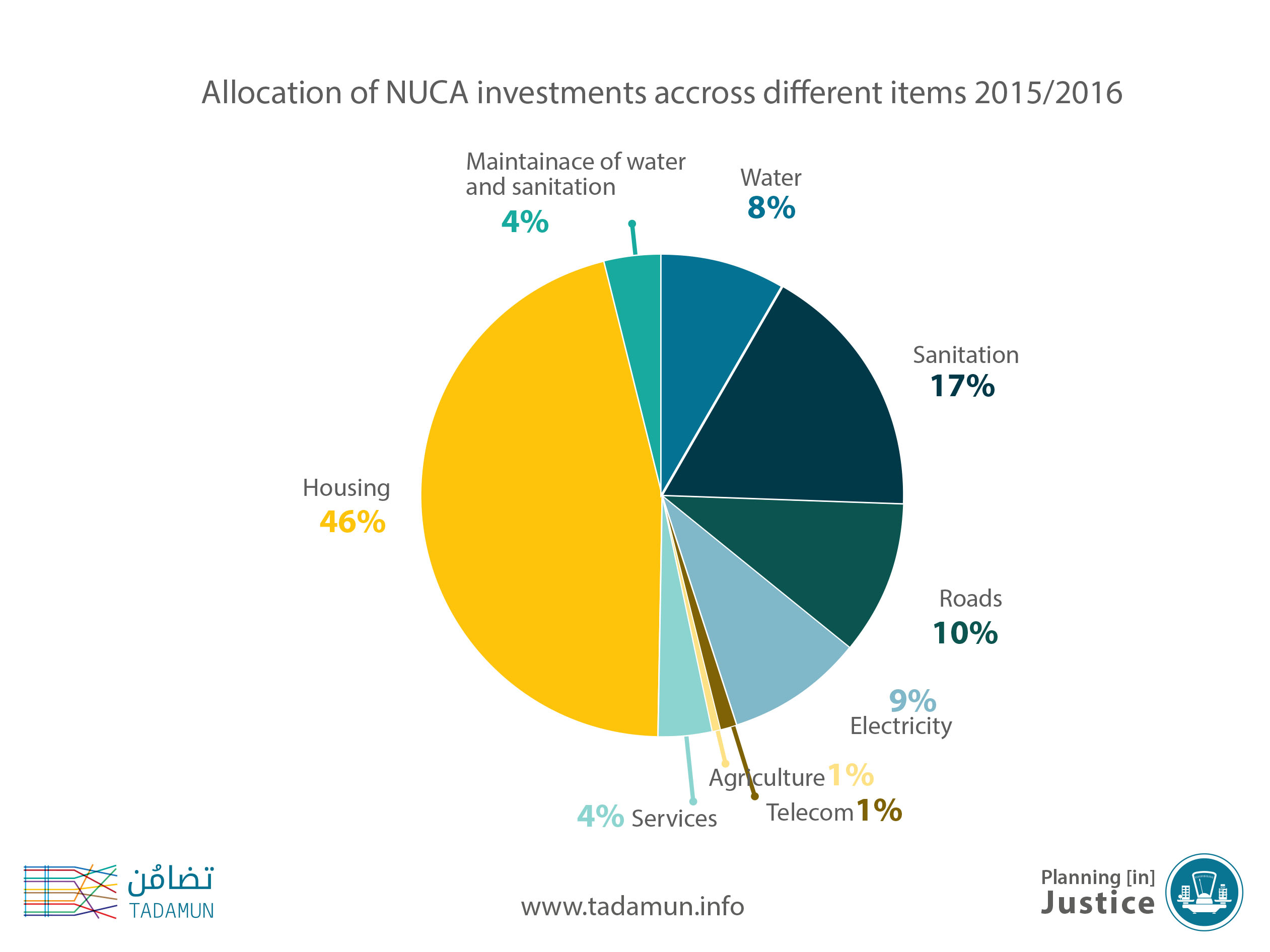

NUCA’s 2015/2016 total budget is 64.6 billion, while its budget for projects as per NUCA’s website is EGP 33.2 billion. EGP 5.6 billion of its projects budget has been allocated to New Cairo City alone, while 10th of Ramadan city comes second at EGP 3.5 billion. Public investment in these two cities and in the new capital together constitutes 42% of NUCA’s 2015/2016 projects budget. It is unclear why these cities in particular are absorbing so much of NUCA’s budget. As for the allocation of NUCA’s investment among the different sectors in 2015/2016, as is depicted in the image below, the bulk of investment goes towards housing, followed by sanitation, then roads, electricity, water, infrastructure maintenance, services, telecommunications, and agriculture.

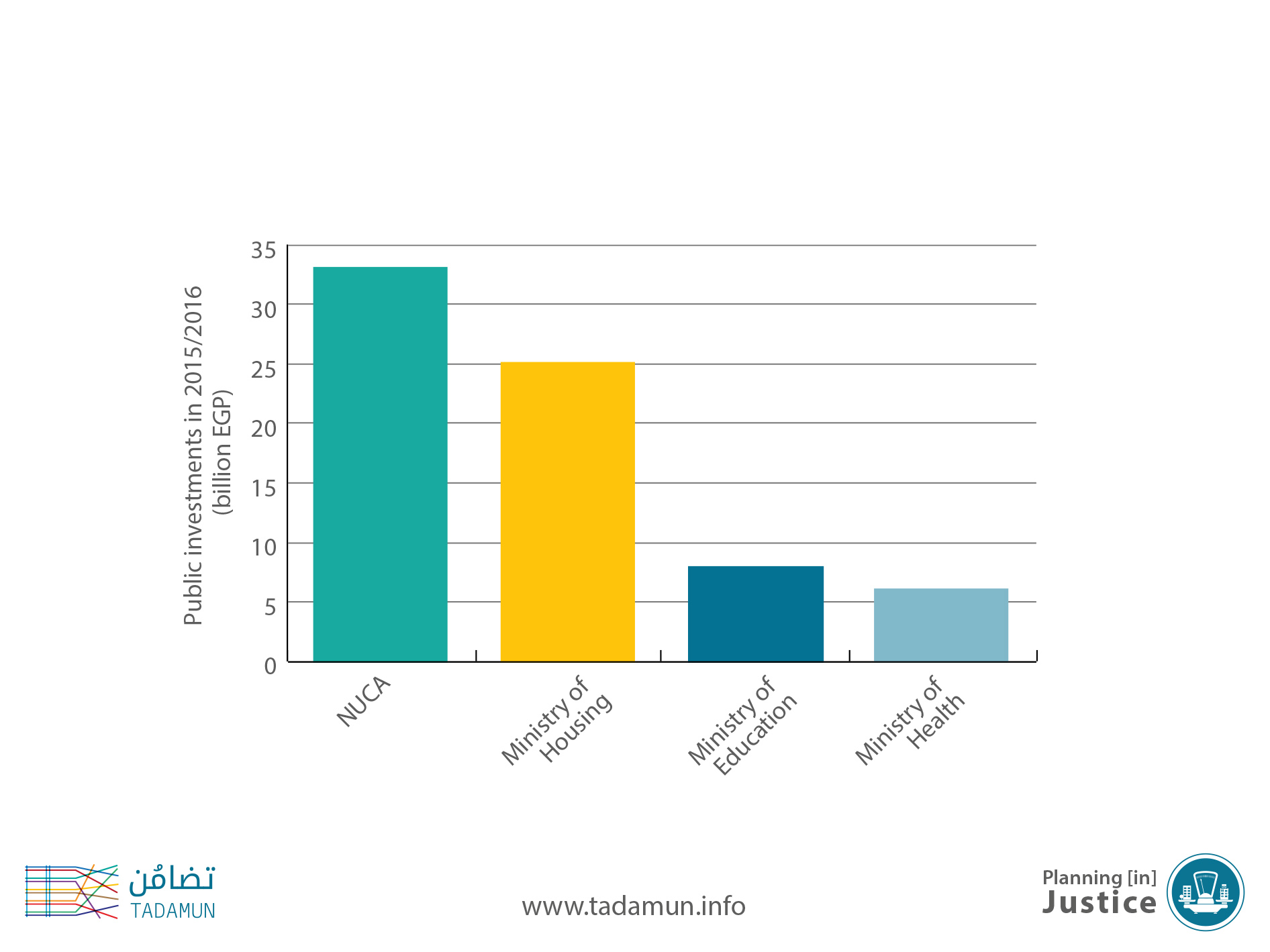

In fact, NUCA has substantially increased its spending on new cities in the past year.10 The total value of NUCA investments in new cities in 2014/2015 was EGP 7.3 billion and that same figure in the 2015/2016 plan is EGP 26.2 billion, in addition to EGP 5 billion going towards the new capital and EGP 2 billion to the Million Feddans Project. The gross total of NUCA’s investment in new cities is EGP 33.2 Billion, almost four times the total public investment in the entire national education sector, and more than five times the total public investment in the health sector during the same year. By contrast, the former Ministry of Urban Renewal and Informal Settlements had a budget of EGP 0.6 billion for that same year. Admittedly, MURIS had very different tasks than NUCA (e.g. MURIS does not install new utilities networks, while NUCA does), but it is still a gross difference that highlights the gap in spending on new cities versus upgrading needy areas in the existing cities.

In addition to what NUCA spends on NUCs, it also absorbs substantial resources for its own operational costs.11 In three successive years the average monthly wage and benefits for NUCA employees per capita were more than three times that of workers in public health and education sectors. According to the final account data for the 2013/2014 public budget for NUCA and for the health and education sectors, the monthly average salary for a NUCA employee was EGP 7,692, compared to an average of EGP 2,272 for workers in the health sector and EGP 2,991 for workers in the education sector12. If we assume that the number of employees is constant, in the 2015/2016 budget the average monthly salary for a NUCA employee is EGP 10,020, while workers–-despite the successive recent increases and application of the minimum wage policy and numerous strikes –-only earn EGP 3,542 in the public education sector and EGP 3,269 in the public health sector (Ministry of Finance, 2015).

Conclusion: Neither Just nor Efficient

Based on the analysis above, expanding the size and numbers of new cities absorbs more than double the allocation for education and healthcare in the whole country together. This brief has described how the new cities have failed to realize their target populations. Perhaps more importantly, however, is that NUCA’s expenditures are increasing at a rate higher than the NUCs population growth rate, which defies the concept of economies of scale, leading to a situation where the per capita amount of money invested to actually move a person to live in a new city is very high. This raises many questions regarding the feasibility and efficiency of the policy.

The NUCA surplus, destined for the government budget, amounted to about 8 billion L.E. in 2016, which was less than 1% of total public expenditure. Despite the size of this surplus and despite its positive impact on decreasing the public deficit, it is still not enough to justify the predominant government rhetoric and popular belief that expanding new cities is healthy for the public budget and Egypt’s economic growth strategies. This is especially important when the government’s claim is not supported by evidence of the policy’s effectiveness, nor how reducing its expenditure on new cities could potentially impact the country’s economic growth.

A minority of land in the NUCs has been allocated towards lower- and middle-income housing yet there is no way to measure if this land allocation is actually meeting the housing demand of such groups. But the bigger issue is that the homes NUCA is building in most cases do not reach the poor and middle classes, and when they do, they do not satisfy their employment, transportation, educational, and other needs.

The new cities presented an opportunity for the Egyptian state to remedy the many problematic issues prevalent in the current local administration system, such as extreme centralization and lack of mechanisms for local participation. Rather than seize this opportunity, unfortunately the new cities not only replicated the same problems, but they exacerbated them even further. During the initial stages of settlement, NUCs are governed by a city authority (gihaz al-madina) which is a subsidiary of NUCA. According to the law, cities, once “complete” should be delivered to their respective governorates, and the city authority should be subsequently dissolved. However, this has not taken place in a single NUC thus far, with the possible exception of 15th of May city which now appears on the Cairo governorate website as a district. Unfortunately, the lack of transparency means that there is no way to find out for sure how many (if any) NUCs have been delivered to the governorates. The presence of two different governance systems creates a dualism in local administration that exacerbates the already-present conflicts and fragmentation.13

Ultimately, the new cities policy has had almost four decades to prove its effectiveness and all it has proven is that it has not succeeded in meeting any of its goals. On the contrary, it has succeeded in deviating from its foundational professed commitment to social justice and providing affordable housing. NUCA has become a real estate agent that deals with the nation’s land as a profit-maximizing resource leading to the distortion of the entire housing market. In light of this, Egypt’s most abundant resource – land – has ironically become its most expensive and difficult to obtain resource. In a just urban governance system, land plays a social function rather than a purely economic one, based on a belief that the city belongs to everyone.14 Through NUCA’s land-commodification practices, this principle has been totally lost, and Egypt’s cities are being developed not for the general public, but for the privileged chosen few.

1.For more on this, see Sims (2014)

2.The 1st generation cities listed on the NUCA website are: 10th of Ramadan, Al-Sadat, New Borg El Arab, 15th of May, New Damietta, 6th of October, and New Salhiya.

3.For more information on the role of international organizations in Egypt’s urban development, see this Tadamun article.

4.The 2nd generation cities listed on the NUCA website are: New Cairo, Sheikh Zayid, Badr, Ubur, New Bani Sweif, New Minya, New Nubaryia, Alshrouk, and Suez Gulf.

5.The 3rd generation cities listed on the NUCA website are: New Assuit, New Tiba, New Sohag, New Aswan, New Kena, New Fayoum, and New Akhmeim.

6.The “target year” is stated when a new city is being planned, so that the planners know what the expected population capacity and growth rates are, and can factor that in when planning for services and utilities.

7.This transfer of governance authority from NUCA to the local administration has not been announced for any of Egypt’s 23 existing NUCs.

8.It is important to highlight that residents of Al-Ubur city have stated in conversations with the Tadamun team that the city is a ghost town, with very few people actually living there. Thus, it is important to remember that NUCA bases its population count on plots sold rather than those inhabited.

9.This amount targeted by the 2015/2016 budget is far higher than actual transfers during the last couple of years. Partially, this increase can be attributed to accounting system changes between NUCA and Ministry of Finance.

10.Nuca’s annual budget is submitted by NUCA to the Ministry of Housing for approval and is then submitted to the Ministry of Finance for final approval.

11.NUCA’s operational costs are not part of the EGP 33.2 billion (which goes entirely towards projects). It is included, among other things, in the EGP 64.2 billion which is NUCA’s entire budget.

12.This number is calculated based on the average salaries for all economic authorities under the housing sector, which are three authorities, the largest of which is NUCA.

13.For more details about the role of municipalities kindly refer to Tadamun Article: “Why Did the Revolution Stop at the Municipal Level?“

14.For more details about the social function of property kindly refer to Tadamun article “Social Function of the City and of Urban Property in the Egyptian Constitution”

References

Abouelmagd, D., 2011. HOUSING FOR THE LOW INCOME GROUPS IN GREATER CAIRO: AN INTERPRETATION OF POLANYI’S MODES OF ECONOMIC INTEGRATION. Presented at the N-AERUS XII, Madrid.

DNE. (2012). A closer inspection of Cairo’s ghost towns. Daily News Egypt.

El-Kadi, Galila. (1992). Case Study on Metropolitan Management (Greater Cairo, DePapers).

El-Sayed, Shawky. (2015). Al-Iskan Al-Igtima’i: Bain Al-Ashwa’eyat Wal Amn Al-Qawmy. Al-Masry Al-Youm.

IskanAlZil. (2013). Government Urbanism: New Cities.

Sims, David. (2014). Egypt’s Desert Dreams: Development or Disaster. American University in Cairo Press.

Shawkat, Yahia. (2014). Policy Note: How Not to Support the Undeserving and Discriminate Against the Poor – EIPR Recommendations on New Income Conditions for the Social Housing Project. The Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights.

NUCA. (2015). Real Estate Regulations for the New Urban Communities Authority.

Tadamun. (2014). The role of international Organizations.

Tadamun. (2015). Know Your City: Masakin Uthman.

Yahia, Fatima. (2015). Al-Ism Mudun Gadida Wal Fe’l Mudun Ashbah. Al-Ahaly.

Comments