The Facebook Diaries of Cairo’s District Chiefs: A New Space for Municipal Dialogue and Accountability?

What are Yawmiyyāt Raʾīs Ḥay?

Image 1: The ʿAin Shams District Chief’s Facebook page is a typical example of Yawmiyaat Ra’is Hay pages formatting and style.

Source: ʿAin Shams District Chief Facebook page, 2016.

After the 2011 revolution, unregulated traffic, informal urban growth, street vendors and the contestation of regulations and authorities increased throughout Egypt. Some residents took advantage of the political power vacuum by quickly constructing or renovating buildings, often illegally.

Many Egyptians complained about ‘encroachments,’ which often competed with established markets, workshops, zoning codes, and other businesses. The proliferation of these ‘encroachments’ was a nuisance to some, while others exploited the new situation: they

extended their businesses into the streets or opened new ones without proper licensing, added illegal stories to their apartment building, or hawked clothing or commercial products in the streets and sidewalks, compounding already challenging traffic and pedestrian safety conditions.

In the fall of 2013, cooperation between policemen and local authorities to reverse urban encroachments grew as General—and then President—Abdel Fattah al-Sisi took power. The military and security forces made a comeback and the balance of power shifted toward centralized state, security, and military institutions and their local actors at the district level.

In September 2013, a few months after President Morsi’s ouster, the appointed Governor of Cairo started a Facebook (FB) campaign entitled “Diaries of a District Chief” (Yawmiyyāt Raʾīs Ḥay), which focused on the role played by the District Chief (DC). This campaign included thirty-three separate Facebook pages, each dedicated to a particular neighborhood within Cairo.1 District Chiefs are public officials appointed by the Prime Minister. They represent the central government at the district level in the city of Cairo and ensure that central government policy is implemented in the district according to the national plan and annual budget.

Over two years, the DCs presented what local administrations had accomplished in their districts and the challenges they faced on their Yawmiyyāt Raʾīs Ḥay pages. These Facebook pages also generated a space for communities to learn about their districts, connect with their local administrations, post their complaints, and express their dissatisfaction with the DC or other aspects of local government rule and policies. Yawmiyyāt Raʾīs Ḥay pages offered a platform for sharing knowledge and experiences, and fostered competition and motivation for improved performance of local districts and its officials.

This campaign had several possible motives. First, it was undoubtedly an effort to improve the image of local government. For years, employees of the local government, which falls under the Ministry of Local Development, were often accused of rampant corruption and cronyism. Consequently, this campaign served to produce a new image of local administration (LA) based on transparency and communication (in Egypt, local government is referred to as local administration or LA).2

Second, the Yawmiyyāt Raʾīs Ḥay pages may have been at attempt on the part of the District Chiefs and others in the government to limit the popularity of the Muslim Brotherhood, particularly at the local level. By improving communication and public service delivery, the government could undercut opportunities for the Brotherhood to gain popularity and support from local residents. The Muslim Brotherhood and other Islamist groups were popular among many lower-income, informal, and underserved areas because they often had provided critical goods and services such as financial aid, food, educational services, healthcare, sports facilities, and youth programs, augmenting, if not competing with the government’s provision of goods and services.3

To understand the Yawmiyyāt Raʾīs Ḥay campaign’s scope, impact, and motivations underlying it, TADAMUN monitored and analyzed the activity on the Facebook pages of four of Cairo’s District Chiefs. The Facebook pages highlighted a number of questions about the relationship between a District Chief, the local administration, and a community. What roles do the DCs play? What are the reasons for community dissatisfaction? Does the criticism and dissatisfaction expressed in some of the FB pages suggest that a re-examination of Local Administration Law 43 in Egypt—the basic law which defines the authority and administrative reach of LA— is needed to increase public accountability of local decision-making and local rule?

Methodology

TADAMUN selected four districts in Cairo and observed their District Chiefs’ Facebook pages during the same one-month period. Each of the four selected districts represented a different region of Cairo (West, East, North and South).4 Tadamun’s team analyzed the FB pages’ posts that listed DCs actions, as well as the community’s comments. A random selection of other district pages during various time periods were also surveyed to check if the results were similar and could be generalized.

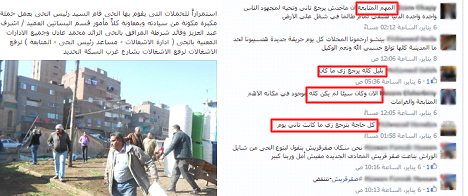

The Facebook pages that TADAMUN observed follow the same basic structure. They include a short description of their objectives under the “About” tab, posts by the District Chiefs, pictures, and comments by residents. Page descriptions vary somewhat in content. The Ain Shams district page, illustrated in Image 1, is a typical example (see above). It states that the aim of the page is: “to display the achievements of the DCs and communicate with citizens to present problems and find solutions that could improve the quality of living in the quarter” (Ain Shams FB page, Feb. 2016). Image 2 below of Manshiyyat Nāṣir DC page, shows the three main components: posts, photos, and residents’ comments.

Image 2: The Manshiyyat Nāṣir District Chief’s Facebook page displaying three main components: posts, photos, and comments.

Source: Manshiyyat Nāṣir District Chief Facebook page, 2016.

Posts

Posts from the District Chiefs about urban issues comprised the bulk of content on the FB pages. Some, but not all, of these posts had headings and generally included a short description of an action taken by LA under the leadership of the District Chief. Many posts mentioned the names and positions of the officials responsible for that specific decision or policy. The posts were updated weekly and sometimes daily. Actions described in posts may be categorized into three groups:

(a) Encroachment Prevention: Those actions implementing regulations to prevent encroachments such as removing street vendors, illegal construction, etc.

(b) Quarter Development: Such actions were usually limited to washing or sweeping streets, improving street lighting, etc.

(c) Provision of New Services: These new services could include opening of new schools or hospitals, for example. The financial and administrative resources of District Chiefs are quite limited, however, and national ministries and their regional operational centers control and distribute many typical public services, such as education, sanitation, or water. Thus, DCs were unable to provide many new services (Tadamun 2013a).

Photos

The second major component of the FB pages was photos attached to posts by the page administrators. One or more photos accompanied almost every post. The photos attracted resident’s comments and people often pointed out the favoritism and irregularities inherent in the local administration’s policies (explained in more detail below).

Residents’ comments

A third part of these pages included comments from district residents about each post. Almost all posts in the thirty-three FB pages drew a minimum of two comments from local residents. Comments were in some cases positive (encouraging the DCs to go further with their actions) but in many cases members of the community voiced dissatisfaction. Furthermore, many of the ‘followers’ of individual FB pages complained about other issues not related to the DCs’ posts. Some tried to highlight other critical problems in the district such as the impact of poor sanitation drainage on community health, while others wrote about how illegal activities negatively affected them. Local government officials rarely reacted to such posts or engaged in a discussion when the public expressed dissatisfaction about an unrelated topic.

The number of ‘followers’ of the FB pages was considerable, indicating a significant interest among residents to learn about their District Chiefs, local officials, and government interventions. The numbers of followers in working-class districts ranged from 3000 to 7000 during the period of observation (January-February 2016). Commercial quarters such as central Cairo had a more limited number of followers (364). Middle class areas such as al-Maʿādi and Madinat Naṣr, attracted more than 12,000 followers. This variation in online usage and access rates may be due to different levels of education and wealth across urban areas.

Analysis: What do the Yawmiyyāt Raʾīs Ḥay Pages Really Tell Us?

A. District Chiefs’ Mandate: Limited Administrative and Financial Capacities

Analysis of the FB pages posts revealed an important trend. The DCs used the pages to take personal credit for what should have been rather mundane or routine activities. For example, “As part of efforts of Mr. /Ms.…the streets were cleaned“ or “rain water was drained from the streets.” DCs also often listed administrators and officials responsible for an intervention, drawn from various departments and levels, such as the District Chief Assistant and Utility Police Officers.

In other words, the FB pages tried to show how the DCs and their teams were working together and doing a good job. This seems rather odd, since such work is far from exceptional and should be accomplished without the need for publicity or significant leadership on the part of the DCs and their assistants. Upon reading such posts, several questions come to mind. For example, how much power does the DC really have to respond to resident’s needs? And how does he govern the district?

Image 3: Photo posted on the al-Waili District Chief’s Facebook page depicting seemingly routine work- street sweeping.

Source: al-Waili District Chief Facebook page, 2016.

Image 4: Another photo posted on the al-Waili District Chief Facebook page depicting other routine work – public lighting.

Source: al-Waili District Chief Facebook page, 2016.

In Egypt, the Prime Minister appoints DCs but they are under the administrative supervision of the Governor (whom the Prime Minister also appoints). They receive considerable direction from the Ministry of Local Administration. All DCs are members of the Governorate’s Executive Council and thus play key roles in planning, budgeting, and monitoring all governorate activities. 5 They also have extensive financial and administrative mandates (Local Administration Law 43 of 1979, Section 2, articles 63-65).6 According to the law, DC’s duties include forming and leading the Executive Council (EC) or Majles Tanfidhi with the participation of heads of all executive departments within the District and the District Secretary.7

The Executive Council has numerous responsibilities including levying certain taxes, evaluating and monitoring projects and public service delivery, and proposing the allocation of investments on the district level. It also helps the DC in preparing administrative and financial plans for the district. In the case of Cairo, there are three levels of strategic plans (national, regional, and governorate) prepared by the General Organization for Physical Planning (GOPP) and its subdivisions.

At the Governorate level, the Governorate’s planning and urban development department is responsible for preparing “detailed plans,” another level of urban plans, which define building and planning regulations, programs, and development projects (Law no. 119, articles 9, 11, 14 and 15).8 The law stipulates that these plans should be prepared with the participation of local units, people’s councils, and executive authorities. Article 15 also gives the Governorate the responsibility to prepare temporary plans and regulations if the GOPP has not yet covered or articulated certain issues. Detailed plans serve to define local needs and project priorities at the local level within the national strategic plans and regulations prepared by the GOPP. They determine construction needs, planning for land use, infrastructure projects, and urban design projects.

Yet, District Chiefs face considerable administrative and financial challenges when trying to suggest priority projects to the governorate for its planning process. At the administrative level, the hierarchical nature of Egypt’s political system concentrates power with the ministries and limits the power of local officials. Ministries typically impose their central plans and agenda on regional and local administrations, leaving little room for local administrators to address the priorities identified at the local level.9 Local administration is also limited financially by this centralized system and has little autonomy to allocate resources according to its own priorities. The DC, the Executive Council, and the LPC are therefore obliged to adopt and implement the central government plans and policies, yet DCs have little financial capacity to address what they think are their communities urgent needs.

The fact that DCs are appointed rather than elected reinforces this tendency, making DCs more accountable to their superiors in the Ministry of Local Administration, the Governor’s office, or other powerful bureaucratic agencies, than to their local constituencies. The last time seats on the lowest level of political representation, the Local People’s Councils (LPCs), were contested was in 2008. 10 In June 2011, after the overthrow of the Mubarak Government, the new provisional government dismantled Popular Councils since they were a stronghold of the previous regime’s National Democratic Party’s (NDP). Thus, local residents have been unable to represent their interests and concerns in an elected body since 2011, although President al-Sisi and the Egyptian parliament have promised that municipal elections will be scheduled soon.

DCs do not often describe the administrative and financial challenges and limitations that they face to the public when they discuss their policies and interventions, and, when criticized, they do not explain that their actions are dictated by the central government’s planning and agenda. They also make little effort to explain how they are mandated to uphold the rule of law and protect the public from illegal encroachments such as illegal constructions or street vendors. As such, residents tend to be unaware of national and regional plans and policies, or of the regulations from higher up that the DCs have to implement.

As discussed above, the District Chiefs head the Executive Councils (Article 64 of Law 43) which are found on both the district level and the Governorate level. Meanwhile, the heads of the districts’ departments sit on the same council (Article 65 of Law no. 43).11 These two articles of Law 43 create an inherent contradiction in the work of the DCs and the Executive Councils: the DC is the one who follows up and evaluates the performance of different departments and directorates. But, how can he/she supervise them when Article 65 makes the heads of department and directorates members in the Executive Councils, which the DC leads? Does this arrangement suggest that the department heads are expected to supervise themselves?

This arrangement impairs the DC’s role as leader of the Executive Council and compromises the very function of Executive Councils. It is unsurprising, under such circumstances that actions that require the participation of multiple departments encounter obstacles. The level of collaboration one would expect in municipal work may be hard to achieve in the absence of an empowered leader to direct the team. Due to the conflict of interest inherent in the work of the Executive Councils, the proper functioning of administrative and executive departments is seriously impaired. FB pages highlight this issue, as they are replete with references to encroachments that point to management failures at the local level.

B. Community Perception of DCs and Local Administration Officials

The second trend that the analysis of the Yawmiyyāt Raʾīs Ḥay pages revealed is dissatisfaction and skepticism among Cairo’s residents. Local residents commented on almost every District Chief’s action posted on the FB pages. Some acknowledged DCs efforts, encouraged them, and pointed out new or additional areas that needed their attention. The majority of comments, however, suggested skepticism about the interventions which residents often labeled “fake” or “superficial.” In the four observed districts, criticisms tended to focus on three issues: perceived inequality, ineffectiveness, and increased and unnecessary force used by DCs in their operations.

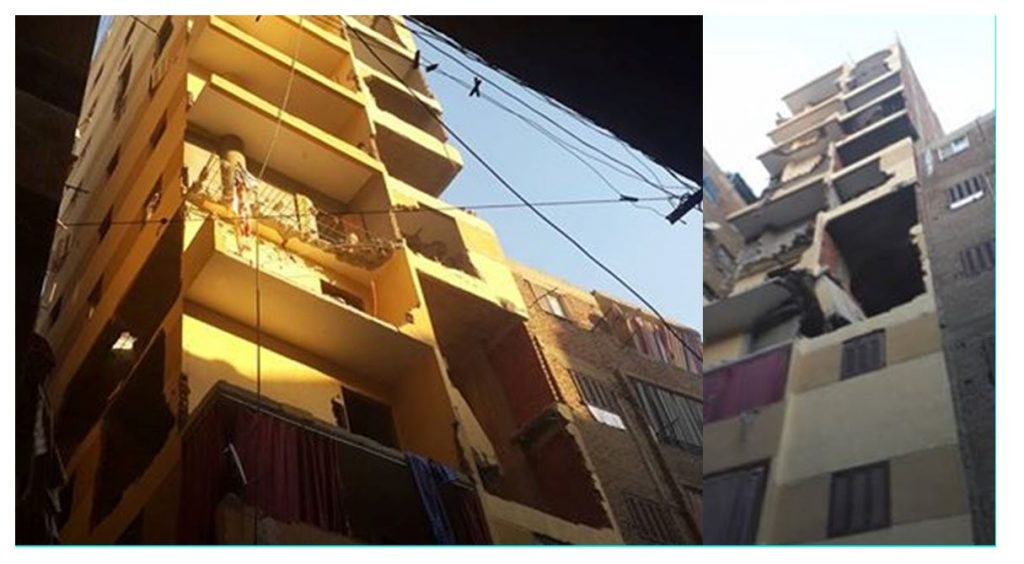

Image 5: Two buildings scheduled for demolition in al-Basatīn due to illegal construction of additional floors, which are perched rather precariously, perhaps posing a danger to the attached buildings.

Source: al-Basatīn District Chief Facebook Page, 2016.

Image 6: Shutting down a street vendor in al-Maṭariyya and impounding his goods.

Source: al-Maṭariyya District Chief Facebook page, 2016.

Inequality

Many residents who posted comments on the Facebook pages expressed their dissatisfaction with DC interventions that harassed powerless or poor people such as street vendors or hawkers. Frequently, the residents wondered why the DC addressed illegal actions in one spot but ignored the same issue in other nearby areas, sometimes on the same street. Residents pointed out that DCs targeted the powerless, while ignoring encroachments by the well-connected. Many chided the authorities with phrases such as “tetshataroh a’la al-ghalabah,” or “you’re just flexing your muscles against the weak.” People’s awareness of these inequalities and their empathy for its victims diminished their trust in, and respect for, local government.

Other residents emphasized widespread corruption as the underlying reason for this inequality before the law. Officials were selective with interventions, some claimed, because they accepted bribes. “The DC has no plan for the quarter, nor does he wish to enforce good order because none of this would help him collect bribes, but he prefers to focus on licensing issues in order to collect bribes,” said one resident (Ain Shams FB page, Jan. 2016).

Image 7: The ʿAin Shams District Chief and his team impound a food cart.

Source: ʿAin Shams District Chief Facebook Page, 2016.

![Image 8: Removing street encroachment of an illegal sidewalk coffee-shop and fūl cart [a breakfast mainstay in Egypt of stewed broad beans]. Source: ʿAin Shams District Chief Facebook page, 2016.](http://www.tadamun.co/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/TAD-PA-DC-7-1024x401.jpg)

Image 8: Removing street encroachment of an illegal sidewalk coffee-shop and fūl cart [a breakfast mainstay in Egypt of stewed broad beans].

Source: ʿAin Shams District Chief Facebook page, 2016.

Residents also commented upon the ineffectiveness of Local Administration policy. Many of them, whether approving or disapproving of the local government’s performance, mentioned the government’s inability to follow-up (mutaab’a) their policies with the next logical steps. Some residents noted that not long after the LA acted, the situation which had required government intervention, reverted to its former condition. Some residents even posted photos of these ineffective interventions, which quickly reverted to their original state. As a resident of ʿAin Shams wrote: “What is the use of interventions if there is no follow-up and no continued interest on the part of the LA, or are you just posting photos for the hell of it?”

Image 9: al-Basatīn District Chief’s campaign to remove encroachments on Gharb Sikak Hadīd Street. Four out of seven comments highlighted how, later that night, the situation returned to its previous condition before the District Chief’s intervention.

Source: al-Basatīn District Chief Facebook page, 2016.

Increased Use of Force

Finally, some residents noted the increased use of force and the “militarization” of the district officials’ enforcement policies. While interventions by officials were less antagonistic in 2013, official ‘interventions’ to remove vendors, street encroachments, or illegal buildings grew more forcible and more militarized by 2016. Image 10 below of volunteers participating in cleaning and beautifying streets in al-Maṭariyya District stands in contrast to image 11 of security forces removing illegal encroachments.

Image 10: Interventions in 2013 after President Mursi’s ouster.

Source: al-Maṭariyya District Chief Facebook page, 2016.

Image 11: Interventions in al-Maṭariyya in 2016 following the election of President al-Sisi.

Source: al-Maṭariyya District Chief Facebook page, 2016

In summation, a number of factors combine to limit District Chiefs capacity. The centralized system of governance limits the DC’s administrative and financial autonomy. The method of selecting the DC (appointed not elected) renders the DC more accountable to the central government than to residents’ needs and priorities. The bureaucratic structure of the Executive Councils creates additional red tape. Moreover, the DC’s minimal efforts to explain administrative and financial constraints they face to the public contributed to the gap between local administration capabilities and resident expectations.

Public perceptions of the DC remain largely unfavorable, despite the DCs efforts to improve their communication with the residents. Perceived inequality fueled by widespread corruption, ineffective LA actions taken to remedy illegal encroachments or address development needs, and the increased use of force by the LA seem to be the major factors that perpetuate these negative views of the LA.

The Way Forward: What Can the Yawmiyyāt Raʾīs Ḥay Facebook Pages Achieve?

The Yawmiyyāt Raʾīs Ḥay Facebook pages may have the potential to be an effective method for improving relationships between local administration and residents. They can provide a counterbalance to the central government and to policies that the local communities find problematic or neglectful of their needs and priorities. Thus far, however, the pages largely portrayed the ineffectiveness, unjust, or unequal actions of the local administration as the latter tried to satisfy central government priorities and objectives.

Facebook as a Space for Deliberation

Despite the negative views of some District Chiefs, the Facebook pages have managed to encourage discussion and dialogue between DCs and local residents within the span of two years. However, this discussion has been more confrontational than productive, to date. The work of DCs and local officials seemed hindered by conflicting administrative mandates and the fact that they operate under policies that they do not create, but which central ministries with far more power and resources stipulate and enforce. Meanwhile, local residents used the pages to express grievances and demands for adequate service provision, which the Ministry of Local Development has little control over. Residents were not always aware of these bureaucratic lines of authority and budgetary mandates, and as such, have few channels to hold district officials accountable to their concerns and complaints.

The Yawmiyyāt Raʾīs Ḥay Facebook pages offer a glimpse into a virtual space that DCs created to illustrate their achievements and to satisfy the central government. Yet, interestingly, their constituents used this same space to initiate serious discussion. Many residents raised important issues not only on the local level but also on the national level. In a few cases, a dialogue ensued with the DCs and their feedback to residents was a medium for some DCs to appreciate public needs more constructively and, at the same time, to explain to the public the administrative and financial limitations DCs face. While this was not a common practice throughout the thirty-three pages of District Chief diaries, there were some interesting cases of effective dialogue and public engagement.

On the Facebook page for the al-Waili District Chief, one resident expressed discontent about “…al-Waili neighborhood, from Ahmed Najīb Square and Mukhtār Pasha Street… the dilapidated cars and the trash.” The District Chief (or the page administrator more likely) replied: “Mr. Adil wants you to know that your message was received and that we are currently working on the matter. If God wills, tomorrow morning, the cars and the trash will be removed (al-Waili District Chief Facebook page, 2016).”

On the ʿAin Shams’s FB page, a discussion emerged between some residents and the DC about removing illegal buildings in 2016. This type of intervention often invites different reactions from various interested parties: DCs, contractors who benefit from the illegally constructed or unlicensed buildings, and residents who are harmed by the same buildings and the new obstructions to their sunlight, views, or public space.

Image12: The destruction of an illegal, informal shop.

Source: al-Maṭariyya District Chief Facebook page, 2016.

In this discussion, a resident asked the DC: “Why would the DCs allow unlicensed apartment buildings to be constructed and then turn around later and raze them, instead of stopping the construction of buildings from the beginning?” The DC then tried to explain the inadequate laws and regulations, arguing that he has no other legal option but to remove building encroachments (i.e., tear down buildings or condemn them) after the fact. Following the DC’s response, residents confronted the DC with other facts. One said: “Why would you focus on removing illegal buildings while the ‘Reconciliation Law’ is about to be passed by Parliament?” (ʿAin Shams FB page, 2016).12

In another exchange, contractors and residents confronted DCs to protest the removal of the illegal buildings. The question of inequality arose in the course of discussions between residents and the DCs regarding the removal process. At one point, the DC invited interested residents to a meeting to address the existing problems and explore ways to improve the situation. In one of the FB posts, the ʿAin Shams DC (or the page administrator) writes:

People are upset about removals…but there is one question: Why do people build illegally? There has been a lot of corruption, including the illegal construction of added floors in buildings. For example, when the District issues a building code violation, it usually discovers that these added floors were written under a deceased person’s name, invalidating the violation. The most important aspect, in my opinion, is that contractors are aware of these problems, but still fail to obtain building permits. All in all, the Reconciliation Law will be ratified soon. So, my phone is available at any time; let’s come together and discuss these problems (ʿAin Shams FB page, February 12, 2016).

A few days later, the DC posted a copy of a document in which a legal consultancy firm affirms that the building permit for the ʿAin Shams District is valid. The post informed the residents skeptical of the legal process behind the approval of a building permit and established a line of communication between the DC and residents. The status update reads: “The dream has come true: the building permit is valid with a signature” (ʿAin Shams FB page, February 16, 2016). This particular exchange seemed to illustrate the need to change the existing system and laws.

Although instances of dialogue, such as the case above, are few in number across the thirty-three pages of District Chief diaries, there were some other promising cases of effective dialogue and public engagement. Such practices, if fostered, can lead to improved state-citizen relationship in the future. It also highlights the positive role that social media can play as an accessible and transparent communication channel: Facebook can create a space for public discussion if the local administrators are serious about learning more about the problems in their districts and engaging residents in a dialogue to improve urban policy.

Yawmiyyāt Raʾīs Ḥay as a Space for Building Trust?

The government’s neglect of local needs and a widespread perception that government officials are corrupt and favor the powerful and well-connected has deteriorated the public’s trust of government over the past few decades. This distrust is amplified when DCs and other local officials act without local monitoring. As an effective platform for educating the public on the scope of authority of local administration, showcasing the LA’s efforts, and allowing residents to communicate their grievances, the Facebook diaries might be used to rebuild trust between the community, the local authority, and DCs.

However, the majority of residents’ comments on the Facebook pages continue to highlight widespread perceived inequality, corruption and inefficiency. This may reinforce and perpetuate the public’s negative impression about inequitable and ineffective local government performance and policies. Therefore, it is crucial for DCs not let these pages backfire by ignoring or failing to respond effectively to the public grievances voiced by the residents on their pages. It is also important for the DCs to explain repeatedly their limited ability to respond fully to local needs or to locate additional resources, while they are mandated to implement national policies, plans, projects, and regulations.

Conclusion

District Chiefs and the Cairo Governorate created these Facebook diaries to highlight the achievements of local administration, from routine municipal duties like street sweeping, to larger public projects like the renovation of a youth community center. Due to the participatory nature of Facebook as a medium, these pages produced a platform for broader state-society engagement on the quality and scope of local government work. Through their posts, District Chiefs (or their page administrators) not only showcased their teams’ achievements, but also shared information about the bureaucratic and budgetary challenges they face, and insights behind the decision-making process. Posts on various local projects were subject to publicly visible comment sections, through which residents were able to express concern, frustration, and praise, and also suggest other areas in need of local development attention.

Often, residents’ comments went unacknowledged, but in many cases they garnered responses from District Chiefs and even sparked back-and-forth dialogues. This sort of discussion between residents and District Chiefs on FB pages may provide an opportunity to build valuable relationships between the community and the local administration. It can rally local support for important issues, promote participatory development and urban planning that is locally contextualized, and influence decision-making that caters to the needs of the local community rather than the precepts of the central government. Through such a dialogue, the voices of the local community may be heard and thus provide legitimacy and momentum to proposed urban plans.

Moreover, District Chiefs face considerable obstacles in their work due to inadequate or outdated laws and problematic power dynamics. Enhanced transparency into local government decision-making, such as the kind generated by the Yawmiyyāt Raʾīs Ḥay, may even help the local authorities strengthen their proposals for development or better articulate their districts’ needs and priorities when they interact with higher levels of the Egyptian state.

In her work on new democratic spaces for participation, Andrea Cornwall uses the term “invited spaces” to refer to arenas of participation through which government solicits citizen consultation, or other types of engagement (as compared to “popular” spaces, which are established by citizens independently of, or often against, government [2004]). Though this may not have been its original intention, the Yawmiyyāt Raʾīs Ḥay campaign facilitated new modes of citizen engagement with local officials. These Facebook pages may be seen as a sort of virtual “invited” space, or at least something closely resembling one.

“Invited” spaces may vary in the shape they take and the dynamic of participation they produce. They may be the product of a genuine political will to broaden citizen engagement or simply a bow to political pressures (Cornwall 2004). Though the Yawmiyyāt Raʾīs Ḥay create no institutionalized or legal basis for District Chiefs to respond to community demands, they do open up an (albeit limited) avenue for citizen participation in the daily activities of local government that did not exist previously. As mentioned earlier, District Chiefs are not elected but the Prime Minister appoints them. The sharing of information about decision-making in this office and the public visibility of citizen reactions is noteworthy, in itself. As Cornwall and Coelho state, “[o]pening up previously inaccessible decision-making processes to public engagement can stimulate the creation of new political subjects as well as new subjectivities” (Cornwall and Coelho 2007, 21).

Although the Yawmiyyāt Raʾīs Ḥay produced a new platform for citizen engagement with local officials, they also highlighted the climate of distrust and uneven quality of typical local government policies and actions. The pages demonstrated the serious limitations and inefficiencies of DC policies and the subordinate role that DCs can sometimes play to some of their own employees, the central government, and even powerful, well-connected community members. Moreover, District Chiefs are free to moderate the content on their pages and choose which resident comments to respond to, and which to ignore.

District Chiefs’ Facebook pages or other such participatory spaces are no substitute for the type of institutionalized public accountability that elected local government creates. Yet, at the very least, the Yawmiyyāt Raʾīs Ḥay have become a new space for the articulation of local concerns and interest.

1. The thirty-three areas included six districts in north Cairo (Shobrah, El-Sahel, El-Sharbyah, Rod El-Farag, Hadi’k Alkobah and El-Zaytoun), nine districts in south Cairo: (Old Cairo, al-Basatīn, Dar El-Salam, al-Maʿādi, Helwan, Maasrah, El-Tebine, Torah, El-Saidah Zeynab), eight districts in the center of Cairo (El-Moski, El-Khalifah, El-Mokatam, Bab Alshe’ryah, El-Gamalyah, Abdeen, El-Nozha, Cairo Center), seven districts in east Cairo (New Cairo, Madinat Naṣr, al-Waili, El-Abassyah, ʿAin Shams, El-Marg, al-Maṭariyya, Manshiyyat Nāṣir, Elsalam), and finally one district in west Cairo (Boulaq). For example, see al-Maṭariyya’s FB page. [This division of quarters was articulated by Sarah elDefrawi, and we can’t change it quite now without going back to her, which I don’t want to do. Let’s just leave it like this, although Deena pointed out the classifications are not quite right. I have corrected the transliteration that were in the paper, but others need correcting here.

2. Here we will analyze the pages of “Yawmiyyāt Raʾīs Ḥay” but for further info about local administration in Egypt, please see Tadamun (N.D). “By definition, Egypt does not have local government, but instead local administration—a matter of semantics with wide-ranging implications. To understand this point is crucial to understanding the challenges facing communities in Egypt’s cities. In terms of politics, a local administration is a body that is responsible for the implementation of a set of laws and policies whereas a local government is a body that not only administers laws and policies but also creates them (Tadamun 2013).”

3. Following the downfall and violence against the Muslim Brotherhood in 2013, the al-Sisi government shut down many charities that identified as “Islamic charities” but were not affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood or other Islamist political movements. Some have re-opened but others remain shuttered. For a broader discussion of the extensive growth of Islamic charities in Egypt see Atia (2013).

4. The selection of the four districts was due to the collaboration of S. Eldefrawi with Shehayeb Consultancy in those districts to develop manuals entitled: ‘Maximizing Use Value Manual Set: An Approach to Upgrade Informal Areas” that provide technical support to local government employees to deal with urban interventions.

5. According to Article 32 of the Local Administration Law No. 43, the Executive Council of the Governorate is headed by the Governor and includes vice governors, heads of cities, districts, departments and public agencies of the governorates, and the governorate secretary. Article 33 defines nine mandates of the council to coordinate, plan, implement, and administrate the general governmental policies.

6.Law 43 was modified two times during President Mubarak’s era in 1988 and 1996 but this part of the law was not amended. Three articles (63-65) highlight the power and mandate of the District Chief.

7. “Each level of government administration (every governorate, province, city, and district as well as some villages) had four components before the Revolution of 2011: an executive officer, an administrative staff, an Executive Council (EC) and a LPC (Mayfield 1996). The local administration staff included service directorates, the executive’s personal staff, and a series of development related departments. Each EC was headed by the executive officer and included the executive’s assistant, the chief executives of the sub-governorate administrative units and heads of public departments, agencies, authorities within the governorate as well. The governor could also invite heads of the public utilities to be on the councils (see Mayfield, 1996).

8. To learn more about detailed plans, visit Law No. 119 of 2008 (the Building Law) and TADAMUN 2015. The press sometimes discusses the Governors detailed plans for their city; an example of which can be found as the Luxor Governor discusses plans for the creation of new “Smart City” nearby. See O News Agency (2015).

9. For a more detailed understanding of the institutions which manage Cairo and other cities in Egypt, see Tadamun’s “Know Your Government” section (2013).

10. Before the revolution, Local People’s Councils (LPCs), the representative body of local government, had very little autonomy, no legislative power, few economic resources, and a limited mandate yet the National Democratic Party allowed very little opposition voices to win electoral seats (see Tadamun 2013). In the 2008 election, which only five percent of eligible voters participated, NDP members, who ran unopposed, won 80 percent of the total 52,000 local council seats and of the remaining contested seats, the NDP won 95 percent (see Herzallah and Hamzawy 2008, 1, 5).

11. Heads of service and production departments defined in the executive regulations of Law No. 43, article 60, include: interior, education, health, housing, agriculture, veterinary service, irrigation, social affairs, social security, manpower, supply commerce, electricity, culture, youth and sports, Waqf, Al-Azhar, finance and the agriculture bank.

12. “Removals” are a very sensitive topic since they not only mean buildings are condemned or demolished, or subject to very lengthy court proceedings, but it also means that people lose their housing and investment in these contested properties, which represent a great loss for most families. Local engineers, at the municipal district level, can issue demolition orders, but they can also be contested in court and are often subject to very complicated legal and security processes. Many community residents feel the complicated process is also susceptible to bribery and corruption along the way. The law to reconcile building violations, a first draft of which was announced in May 2014 under former Prime Minister Ibrahim Mehleb, aims to regulate buildings illegally constructed following the Jan. 25, 2011 revolution as a result of encroachments and building code violations. Those in violation of the Building Law prior to ratification of the Reconciliation Law, may appeal to the New Urban Communities Authority (NUCA), as the authorized representative under Article VI of Law 119, to stop pending removals by authorities. After paying a fine, as stipulated under Article II of the Reconciliation Law, NUCA has the right to form a technical committees to come to terms with some building violations, with the exception of: (1) construction of buildings deemed “unsafe”; (2) infringements on zoning regulations; (3) building height violations that exceed restrictions stipulated by the Civil Aviation Authority; (4) violations of parking lot codes and regulations, which include, for example, turning private parking lots into commercial businesses without permits (the law does not specify residential or commercial zones in this case); (5) buildings constructed on land protected under the Archaeological Preservation Law; and (6) and buildings constructed on state-designated property. The technical committee, comprised of a head engineering consultant and two professional engineers in non-administrative positions, approves removals or provides an amnesty period to amend (and ultimately forgive) violations. Approval to the amendments only occur when the structural safety of a building is proven through a building safety certificate issued by the committee upon final inspections. See Al Qarnashawi (2014) for the full draft of the Reconciliation Law.

Works Cited

ʿAin Shams FB page. 2016. Post by ʿAin Shams District Chief responding to complaints from local residents and contractors regarding building violations and building permits. 12 February, 5:59 AM. Retrieved July 7, 2016.

ʿAin Shams FB page. 2016. Photo accompanying a post by ʿAin Shams District Chief showing a copy of a document prepared by a legal consultancy affirming the validation of the district building permit. 16 February, 9:13 PM. Retrieved July 7, 2016.

Atia, Mona. 2013. Building a House in Heaven: Pious Neoliberalism and Islamic Charity in Egypt. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Al Qarnashawi, Shimaa. 2014. “Full Draft of Reconciliation Law.” Al Masry Al Youm. 24 July.

Cornwall, Andrea. 2004. “Introduction: New Democratic Spaces? The Politics and Dynamics of Institutionalized Participation.” IDS Bulletin, 35 (2), 1-10.

Cornwall, Andrea and Vera Schatten Coelho, Eds. 2007. Spaces for Change? The Politics of Citizen Participation in New Democratic Arenas. London and New York: Zed Books.

Herzallah Mohammed and Hamzawy Amr. 2008. “Egypt’s Local Elections Farce Causes and Consequences.” Carnegie Endowment Policy Outlook, Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://www.policyarchive.org/handle/10207/bitstreams/6520.pdf.

Mayfield, James B. 1996. Local Government in Egypt: Structure, Process, and the Challenges of Reform. American University in Cairo Press, Cairo.

O News Agency. 2015. “Badr Yebhath Wad’ Mokhatat Tafseely Estrateejy Le Madinat Al Aqsor.” O News Agency. 29 December.

Ragab, Mohammed. (n.d.. “Nizam Al-Idara Al-Mahleyya Fi Masr.” Partners in Development (PID), Egypt.

Shehayeb, Dina. 2016. “Maximizing Use Value Manual Set: An Approach to Upgrade Informal Areas.” Participatory Development Programme in Urban Areas (PDP), GIZ, Egypt.

Tadamun: The Cairo Urban Solidarity Initiative. 2013. “Why Did the Revolution Stop at the Municipal Level?” June 23.

Tadamun: The Cairo Urban Solidarity Initiative. 2013a. “Who Pays for Local Administration?” June 23.

Tadamun: The Cairo Urban Solidarity Initiative. 2015. “What to Expect from Egypt’s New Building Tax Law?” March 23.

Tadamun: The Cairo Urban Solidarity Initiative. (n.d). “Al Magalas Al Ma’neyya Lel-Ahayaa’.”

Tadamun: The Cairo Urban Solidarity Initiative (n.d.[a]). “Al Magales Al Sha’beyya Al Mahliyya.”

Tadamun: The Cairo Urban Solidarity Initiative (n.d.[b]). “Al Marakez Al Iqlimeyya Lel-Hay’a Al ‘amma Lel-Takhteet Al ‘Omrany.”

al-Waili District Chief Facebook Page (يوميات رئيس حي الوايلي). 2016. Comment by resident on DC administrator post and subsequent reply from DC page administrator. Original administrator post described clean-up and renovation in specific neighborhoods to coincide with the Christian holiday season. 7 January, 1:05 PM and 18 January, 5:13 PM. Retrieved July 7, 2016.

Comments