The Hidden Cost of Displacement: The Move from `Izbit Khayrallah to Masākin `Uthmān

Introduction

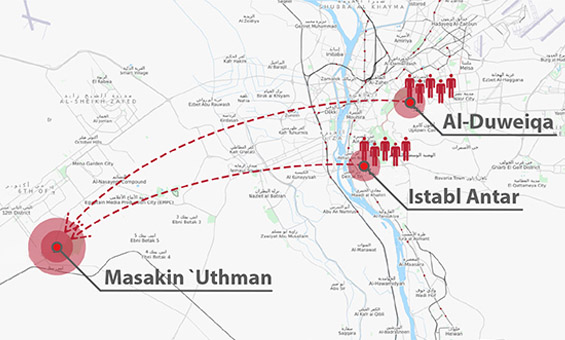

As forms of social and spatial injustice seem to be increasing in the world’s major cities the question of who the city belongs to has never been more salient (Adomaitis, 2013). Displacement of families living in informal areas due to the implementation of public projects or to protect public safety continues to be one of the main issues of conflict between the habitants of these areas and the state. Following a 2008 rockslide that killed over 200 residents of Duweiqa in Manshiyyit Naṣir, an informal settlement in the East of Cairo, the Egyptian government established the Informal Settlement Development Facility (ISDF) to examine and classify the condition of housing stock in informal spaces.

The ISDF determined that a number of homes in the `Istabl Antar area of ‘Izbit Khayrallah, one of Cairo’s largest informal settlements and other homes in Duweiqa, were unsafe and relocated those living there to alternative housing in Masākin `Uthmān, a new area within 6th of October City, one of Egypt’s new urban communities. Within a year, however, many of the relocated families found that life in Masākin `Uthmān created untenable economic and social costs and they chose to return to their old neighborhood, ‘Izbit Khayrallah. The experience of these residents raises a number of questions about urban policies that rely on eviction and resettlement as a means of ‘improving’ informal areas: Do these policies fairly compensate residents for costs incurred during the eviction and resettlement process? Do they fulfill the right to adequate housing? And most importantly, are people’s experience, on the whole, positive or negative after being relocated?

Adequate housing criteria according to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. General Comment 4, (The United Nations, 1991).

Displacement is not a rare phenomenon in Egypt. Between 1997 and 2013, over 40,000 families living in urban areas were relocated, most commonly from inner to peripheral city areas (Shawkat 2013 cited in Thonke 2015). If one considers most Egyptian households include four to six family members on average, the welfare of a more considerable number of people–from 160,000 to 240,000—is at stake. In addition to the more obvious costs of lost homes, land, and the expenses of moving, relocated residents lose the valuable social networks and financial investments they made in their homes, their community, and adjacent economic activities. These hidden costs often remain invisible to policy-makers and are borne by relocated populations alone, to the point that families face more difficult challenges than they did prior to their relocation. Too many ‘beneficiaries’ can become unfortunate casualties of relocation policies.

TADAMUN conducted in-depth interviews with eight families who returned to ‘Izbit Khayrallah after being relocated to Masākin `Uthmān and while the number of interviews may be small, they are suggestive of more broadly shared experiences that our researchers have heard from many others in similar circumstances. This policy brief (i) provides a brief overview of Egypt’s urban resettlement policies and practices; (ii) examines existing approaches to evaluating costs associated with eviction and relocation; and (iii) utilizes the findings of the interviews to highlight the full scope of costs incurred by eviction and relocation policies. The objective of this brief is to situate the experiences of those moved from ‘Izbit Khayrallah to Masākin `Uthmān within the framework of the right to adequate housing and to demonstrate the myriad ways in which resettlement polices negatively impact the lives of relocated people.

Eviction, Relocation, and New Urban Communities

Two general principals of the Egyptian government’s urban policies have resulted in the institutionalization of eviction and resettlement as a common procedure for dealing with informal areas: (i) informal areas are a problem that must be reduced or removed; and (ii) urban growth must be directed toward desert areas and away from existing cities and agricultural land (TADAMUN, 2014). While the exact figure is unknown, an estimated 50% of Egypt’s urban dwellers, or roughly 16 million people countrywide, live in informal settlements, such as ‘Izbit Khayrallah. A comparison of census data between 1996 and 2006 puts the number of people living in informal areas in Cairo alone at 67 percent (Sims 2012). Despite their prevalence, informal areas suffer from underfunding, poor public service provision, and the marginalization of their residents. Government approaches toward informal areas do not recognize informal areas as the dominant feature of Egyptian cities that they are, but rather as peripheral spaces antagonistic to the city and society. Accordingly, urban policies tend to favor resettlement to new cities over upgrading and improving existing building and infrastructure in informal areas.

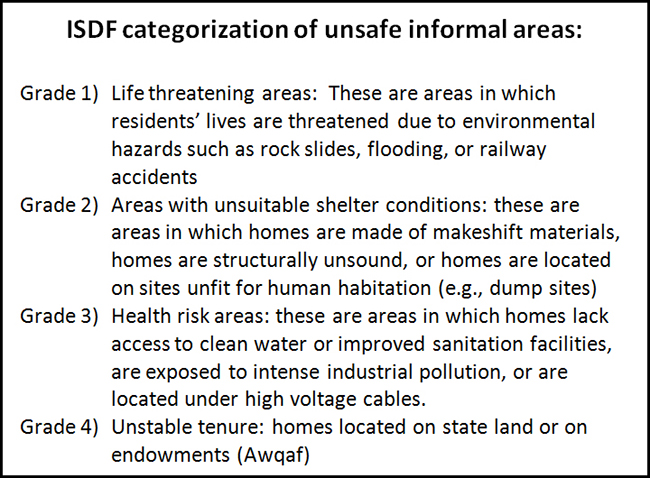

As in the case of `Istabl Antar, where forced eviction proceeded in the name of environmental hazards, the government commonly describes resettlement in terms of public health and safety. The ISDF utilizes four grades for categorizing the safety of informal areas, in accordance to urgency of intervention:

Often, however, established ISDF procedures differ from actual practice. The ISDF grading system requires that the government prioritize resettlement of those residents facing the greatest threat to their safety. In some areas, however, the ISDF evacuated residents living in Grade 2 “poor housing quality” areas before residents living in Grade 1 “life-threatening areas” (TADAMUN 2014). Additionally, areas located on high-value land, regardless of safety grade, are more likely to be targeted with eviction, resettlement, or rehousing than other, lower land value areas. Two areas close to downtown Cairo, the Maspero Triangle and Boulaq, have been targets of major redevelopment projects for many years (TADAMUN 2014). A desire to beautify the city, attract investment, or to profit from the clearing of valuable land often informs government decisions about which areas to resettle and when, rather than an imperative to protect residents and improve housing conditions.

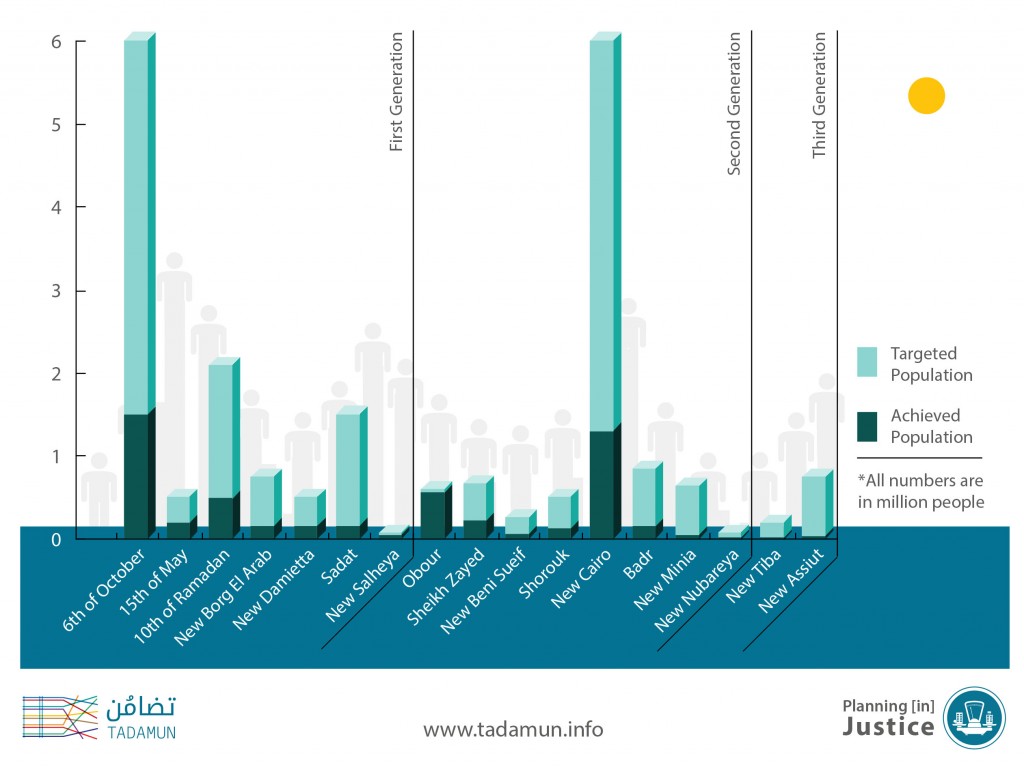

In the 1970s the Egyptian government launched the New Urban Communities (NUC) policy in an effort to redistribute inhabitants away from existing urban areas along the narrow strip of the Nile Valley, to provide housing for low-income groups as an alternative to informal areas, and to alleviate some of the problems facing urban Egypt. While they may offer higher quality housing stock than those in informal areas, the shortcomings of new cities often outweigh the benefits. For the most part, Egypt’s new urban communities fail to provide housing that fulfills the basic adequate housing criteria: they are located on the outskirts of cities far from job opportunities, commercial centers, and with poor access to amenities, public services, and transportation. Because of the long-term hardships relocation imposes on the residents of new cities, the NUC policy has largely failed to accomplish its stated goal. Thus, informal settlements in existing urban areas continue to grow as residents find such housing better suited to their needs than relocating to new cities in the desert. At present, the government has constructed 23 NUCs across Egypt and has plans to build five more (TADAMUN 2014) yet most of these areas have failed to reach their intended population targets.

Estimating the Hidden Costs of Relocation: The Housing Rights Violation Loss Matrix

A key factor resulting in the ineffectiveness of Egypt’s eviction and resettlement policies is that they do not take into account the full scope of losses that relocated residents experience during the eviction and moving process, as well as longer term costs of adjusting to life in relocation sites. The Housing and Land Rights Violation Matrix, developed by the Housing and Land Rights Network (HLRN) of the Habitat International Coalition (HIC) in 2005 (as part of a broader methodology in their Housing and Land Rights Monitoring Toolkit), is perhaps the most comprehensive approach to estimating the full scope of costs incurred by eviction and relocation. It is firmly grounded in a human rights framework, particularly the right to adequate housing, and considers a wide spectrum of direct and indirect, immediate, and long-term costs that may occur throughout every stage of the process. It includes the value of assets in the old community (pre-eviction), costs once the threat of eviction is initiated, costs incurred during the process of eviction, and then post-eviction. A particular strength of this approach is that it accounts for both material and non-material costs. For quantifiable costs, such as land value or lost income, the matrix records specific economic values. For incalculable losses, such as losing or weakening one’s established social network, the matrix records costs in narrative form. As such, items encompassed in this cost calculation include the value of economic assets owned by displaced communities, including houses, inventory, livestock and animals, land, built utilities, etc., before and after displacement, the social assets established in the old and new communities, as well as the cost of the process of eviction itself added to the increases in the cost of living borne by communities after being displaced. The following are the basic elements of Housing Rights Violation Loss Matrix:

- Both personal costs experienced by victims and public or social costs or housing rights violations;

- The material and otherwise calculable costs resulting from the violations are determined for each unit (i.e., household) affected and then added together;

- In the case of multiple units affected, a representative sample is obtained to determine the average values, which then are to be multiplied by actual numbers of units affected;

- Incalculable losses recorded and reported in narrative terms. Such narrative explanation and analysis is used as an accompaniment to the quantification table;

- Both short-term/immediate and long-term values;

- Personal injury and pain-and-suffering damages, calculated by using methods derived from applicable local jurisprudence, legal cases, actuary science or international practice (Du Plessis 2011).

The HLRN Matrix assesses over 250 different items which represent costs and losses associated with eviction and relocation. While a comprehensive overview of each of these costs is beyond the scope of this policy brief, the following are some of the key material and non-material losses included in the matrix:

Material Losses

- Plot and physical house

- Contents

- Collateral damage

- Business losses

- Equipment

- Prospective income

- Mortgage

- Livestock

- Trees / crops

- Decreased wages or income

- Health care

- Interim housing

- Bureaucratic and legal fees

- Alternative / replacement housing

- Transportation costs

Non-material Losses

- Environment / ecology

- Standing / seniority

- Political marginalization

- Social marginalization

- Health

- Living space

- Psychological harm

- Disintegration of family

- Loss of community

Examining the move from ‘Izbit Khayrallah to Masākin `Uthmān with reference to the types of costs delineated in the HLRN Matrix highlights the full scope of loss experienced by relocated residents, and sheds light on Egypt’s failed eviction and resettlement policies, more generally.

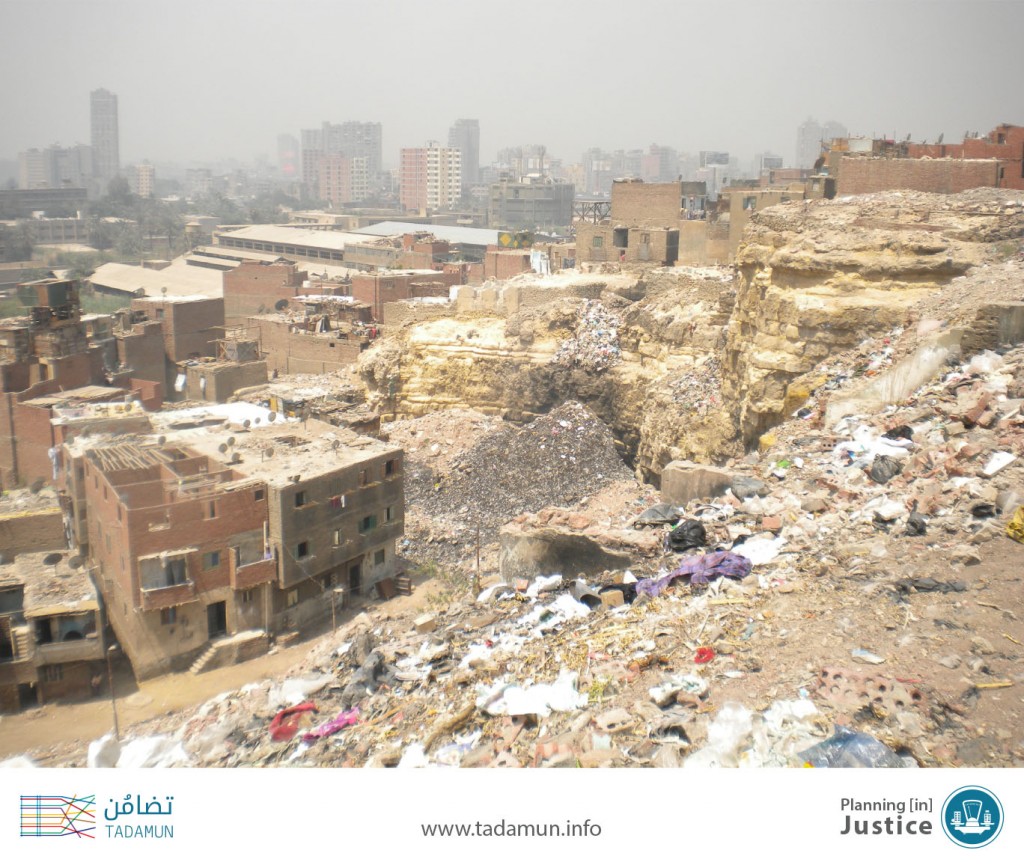

The Case of ‘Izbit Khayrallah

Forty years ago, the area currently known as ‘Izbit Khayrallah was an empty rocky plateau north of Maʿādī. In the mid-1970s, poor migrants from Upper Egypt and Delta cities settled on this vacant land without roads, infrastructure, or services. The migrants came to Cairo looking for work, but could not afford to purchase or rent housing in the city, so they built their homes from the stones available on the site (TADAMUN 2015b). Today ‘Izbit Khayrallah is one of Cairo’s largest informal settlements, with an estimated 650,000 residents (TADAMUN 2013). Situated close to the city center on an elevated plateau overlooking the Citadel, the Pyramids, and even the Nile from its western border, ‘Izbit Khayrallah is a prime location and thus, its land is valuable. It offers residents a multitude of economic opportunities, a high level of social cohesion, and excellent access to transportation. Though poorly served by public services, ‘Izbit Khayrallah is an integrated community where most basic services are available thanks to residents’ collaborative efforts and bureaucratic and judicial struggles (TADAMUN 2013).

After the 2008 rockslide in the Duwaiqa district, the ISDF determined that a number of houses on the plateau’s edges were unsafe for habitation. The government subsequently began the process of evicting residents and transferring them to alternative housing in Masākin `Uthmān. The National Housing Project (NHP) began construction on Masākin `Uthmān in 2005 to provide housing for low-income families. The area’s official name is “al-Awla bi-l-Ri`āya” or “The Most Care-Worthy,” but it is commonly referred to by the name of one of the companies contracted to build the housing units there—Osman Ahmed Osman & Co. (now the Arab Contractors Company). Masākin `Uthmān is located on remote desert land over 40 km from centrally located ‘Izbit Khayrallah, and, like many of Egypt’s new urban communities, is frequently described as a “ghost city” because so many of their buildings remain empty (TADAMUN 2015b).

A number of problems arose during the relocation process. Some residents refused the eviction order and a lack of accurate record-keeping on the part of the ISDF allowed some to abuse the system. As a result, the government ended up providing housing to some residents who were not meant to be evicted and failed to provide housing for some residents who were evicted. Despite these issues, the ISDF proceeded with eviction and resettlement in 2013.

In December 2015, TADAMUN’s interviews illustrate the many ways in which forced resettlement to new cities burdens those who have been relocated quite significantly, often enough to render life in the resettlement site untenable. While the move to Masākin `Uthmān provided an immediate solution to the dangerous condition of their housing in ‘Izbit Khayrallah, it imposed additional, indirect long-term costs, which ultimately cost relocated residents so much that many of them returned to their previous neighborhood. In some cases, the government had already demolished their original homes and they had to find new places to live. The direct, indirect, material, and non-material costs residents experienced as a result of eviction and relocation include:

Direct Costs

Houses: None of the residents interviewed received monetary compensation for their old homes (owners and renters alike). In some cases, the government demolished the old homes, resulting in an uncompensated loss of their investment in their homes. When families returned to ‘Izbit Khayrallah, most of those whose homes had not been demolished could still not move back into their old homes, since they remained on the Cairo governorate’s demolition list. Many of the interviewees had been home-owners and they had built their homes themselves but they were forced to become renters upon their return to Khayrallah. One interviewee had lived in a two-story home prior to eviction and then was forced to rent a single-room dwelling for herself and her family and share a bathroom with other families, after returning from Masākin `Uthmān. This deterioration in her living conditions highlights not only the importance of various kinds of housing stock, their size and value, but also the associated amenities and social hardships which substandard housing entails.

Moving: In addition to receiving no compensation for their old homes, all interviewees reported that they were required to pay EGP 200 – 250 (a considerable sum for them) to move their belongings from ‘Izbit Khayrallah to Masākin `Uthmān.

Alternative Housing: To pay for apartments in Masākin `Uthmān, interviewees had to pay EGP 500 as a first installment, in addition to a monthly payment ranging from EGP 126-150. The monthly rent was not significantly different than what the residents paid in ‘Izbit Khayrallah.

Indirect Costs

Income: All of the families interviewed reported that their income had decreased by more than half its value when they relocated from ‘Izbit Khayrallah to Masākin `Uthmān. Most of the heads of households of interviewed families worked as day laborers or in the informal sector. As such, their ability to generate income was very location dependent. When they were relocated to Masākin `Uthmān most of the families’ primary earners either lost their jobs or had to commute back to ‘Izbit Khayrallah every day. Even after moving back to ‘Izbit Khayrallah, many income earners had difficulty regaining their jobs as carpenters, day laborers, or street vendors.

Poor Public Services: Despite the recent construction of this housing project, it was poorly equipped to suit the needs of everyday life and its infrastructure was very problematic, low quality, and poorly maintained. Some families suffered from unreliable water sources and poor sanitation. Residents were forced to buy water for up to EGP 5–6 per day, since the water supply to houses was unreliable. Additionally, they had to pay a weekly fee to maintain the sanitation network. Public health services were hardly available in Masākin `Uthmān. Interviewees with chronic health problems told TADAMUN that they had to travel to areas closer to their old homes in ‘Izbit Khayrallah to find health care.

Cost of Food: Compared to ‘Izbit Khayrallah, Masākin `Uthmān offered residents few options for purchasing food. Interviewed families reported that their monthly food costs doubled after moving to Masākin `Uthmān and that, due to limited supplies, they had to travel elsewhere to buy food items. As such, residents incurred high transportation costs on top of already higher food prices.

Transportation: All interviewees reported that they faced a tremendous increase in transportation costs after moving to Masākin `Uthmān. Transportation costs rose from EGP 2-4 per person per day to more than EGP 10 for each trip, which caused a particular financial strain for those commuting daily back to ‘Izbit Khayrallah for their jobs.

Livestock: In their previous homes in ‘Izbit Khayrallah, many of the interviewees raised livestock such as geese and ducks and relied on this additional income in a financial crisis or when food supplies dwindled. Alternative housing in Masākin `Uthmān could not accommodate livestock. After relocation, they lost the livestock, the income the livestock could produce, and an important source of protein-rich food.

Non-material Costs

Established Social Networks: Most of the interviewed families stated that in ‘Izbit Khayrallah they had relied on collective savings associations (gama’iyaat) and borrowing funds from nearby neighbors and relatives in cases of emergency. In Masākin `Uthmān, after being uprooted from their families, friends, and neighbors this was not possible since they did not feel the same level of trust among their new neighbors, which informal savings and borrowing vehicles rely upon.

Conclusion

The eight families that TADAMUN interviewed constitute a small sample of those impacted by eviction and resettlement in Egypt. However, their experiences and the costs they identified are representative of the losses such policies commonly incur upon the very people they intend to benefit. As in the case of ‘Izbit Khayrallah, communities slated for eviction and resettlement are home to some of Egypt’s poorest urban citizens; these citizens are especially vulnerable to the multitude of economic, social, health, and psychological costs commonly experienced by resettled communities. Social networks, in particular, are “a critical survival tool for the urban poor, who must constantly [negotiate] . . . economic fluctuations and uncertainty” (Everett 2001: 456, cited in Thonke 2011). Thus, displacing residents of informal areas from their neighborhoods and the various sources of social support available there can have potentially devastating effects on their ability to sustain a decent quality of life.

‘Izbit Khayrallah boasts a long legacy of citizens working together to improve their neighborhoods, combat state negligence, and defend their right to the city (TADAMUN 2013). As a result, a high level of social cohesion and mutual trust allowed residents to rely on social networks in difficult times, through collective savings and borrowing, for example. Uprooting citizens from their homes in `Istabl Antar and relocating them to Masākin `Uthmān deprived them of more than the value of their homes—it exacted a multitude of less apparent costs, many impossible to quantify.

As long as the Egyptian government’s urban policies rely upon eviction and resettlement as a means to address the problems facing informal areas, residents of informal areas will suffer and urban policies will fail. A government approach relying instead on upgrading existing informal areas would offer the possibility to improve housing areas while imposing minimum costs and physical and social disruption upon residents. Upgrading, or insitu development, refers to the gradual improvement of existing buildings and infrastructure without demolishing homes, disrupting the urban fabric, or displacing residents (Del Mistro and Hensher 2009). For 2015/2016, the Egyptian government budgeted EGP 33.2 billion for the New Urban Communities Authority investment in new cities. In comparison, the former Ministry of Urban Renewal and Informal Settlements had a budget of EGP 0.6 billion that same year. This gross disparity highlights the gap in spending on new cities versus upgrading housing and services in existing urban areas.

Rather than continue the burdensome policy of forced relocation to distant and under-serviced new cities, TADAMUN is currently researching the associated projected costs and social returns of an alternative scenario: investing in the in-situ development of ‘Izbit Khayrallah, incrementally and with the participation of local residents. Like all public policy, it is important to analyze in a realistic and detailed fashion, the public and private costs of alleviating the problems of unsafe or deteriorated housing stock and sub-standard services in ‘Izbit Khayrallah. There is sufficient public information and recent analysis to demonstrate that forced relocation and the construction of more new cities may be little more than an ineffectual placebo, which has wasted tremendous public resources and worsened rather than improved the acute challenges of inadequate housing and public services. TADAMUN’s upcoming studies, we believe, will reveal more economical and socially less disruptive strategies of in-situ development, in the short and long term, to improve the lives of residents and the urban challenges in many areas of Cairo. Stay tuned.

References

Du Plessis, Jean. 2011. “Losing Your Home Assessing the Impact of Eviction.” United Nations Center for Human Settlements

Everett, Margaret. 2001. “Evictions and Human Rights: Land Disputes in Bogotá, Colombia.” Habitat International 25 (4): 453–71. doi:10.1016/s0197-3975(01)00015-7.

Habitat International Coalition. 2005. “Housing and Land Rights Network: Housing Rights Violation Loss Matrix.” [Dataset] Accessed December 11, 2015. http://www.hlrn.org/spage.php?id=p2s#.XfFLPpNKjOR.

Sims, David. 2012. Understanding Cairo: the Logic of a City Out of Control. The American University in Cairo Press.

TADAMUN. 2013. “`Izbit Khayrallah and the Struggle for Land: Security of Land Tenure.” Tadamun: The Cairo Urban Solidarity Initiative. December 25, 2013. http://www.tadamun.co/?post_type=initiative&p=811&lang=en&lang=en#.XfPZQ5NKjs2.

TADAMUN. 2015. “Know Your City: Masākin `Uthmān.” Tadamun: The Cairo Urban Solidarity Initiative. April 30, 2015 http://www.tadamun.co/?post_type=city&p=5737&lang=en&lang=en#.XfFMPpNKjOS.

TADAMUN. 2015. “Egypt’s New Cities: Neither Just Nor Efficient.” Tadamun: The Cairo Urban Solidarity Initiative. December 31, 2015. http://www.tadamun.co/egypts-new-cities-neither-just-efficient/?lang=en#.XfPbN5NKjs0

TADAMUN. 2014. “Coming Up Short: Egyptian Government Approaches to Informal Areas.” Tadamun: The Cairo Urban Solidarity Initiative. September 16, 2014. http://www.tadamun.co/coming-short-government-approaches-informal-areas/?lang=en#.XfPbfZNKjs0.

.شوكت، يحيى. 2013.”إعادة التوطين والتطوير العمراني في مصر: 1997 حتى 2013.“ بالرجوع إليه من

http://blog.shadowministryofhousing.org/2013/10/1997-2013.html

Comments