Investigating Spatial Inequality in Cairo

The concepts of poverty, equality, and justice – and the spatial dimensions of each of these – are linked and it is important to understand the differences among these terms and how one can best measure them. Poverty is the count or the proportion of population living below an income level defined by the cost of basic needs in a particular city, region, or country (often called the poverty line). The concept of equality promotes the identical distribution of income and resources to all individuals. The concept of justice focuses on the fair distribution of resources, taking into consideration the special needs of each group.

In Egypt, planning tools are deficient because they do not transparently reflect the actual needs on the local community level, and thus many forms of deprivation remain invisible. The regional planning tools only look at whether an area is “unplanned” or “unsafe”1 yet there are many areas that are both labeled planned and safe but are still deprived of services or suffer from deteriorated infrastructure, etc. On the fiscal planning side, Line-ministry budgets are distributed by each ministry to its directorates in the different governorates, with no way to see how the directorate resources are then distributed at lower administrative level. In general, the distribution of fiscal resources is hardly based on poverty indicators, needs, or deprivation, in practice political bargaining and negotiation between government officials and bureaucratic entities often outweigh any calculation. A very small proportion of public expenditure is managed on the district level, which is allocated for local development programs.

This gap between local development needs – with its comprehensive definition – understood far better at a local level and the unfair amount of government resources for those areas is the main concern of the Planning [in] Justice project. Our project is particularly concerned with designing ways to measure and visualize the distribution of resources between urban areas to assess the minimum resources necessary for long-term survival of particular communities and increase the level of spatial justice through clear criteria that correspond to local needs.

Ideally, complete spatial justice would mean equal access of all citizens to public facilities and/or services, such as schools, hospitals, or cultural centers; jobs; or amenities, measured in distance and/or the number of people served. A more sophisticated definition of spatial justice suggests equal access to their choice of all of the above, meaning that citizens should be able to choose employment options and careers, which schools they send their children to, or which hospitals or health clinics best serve their needs. Spatial justice is about the quality of public goods and services within a neighborhood as much as it is about the quantity.

Analyzing Inequality: From the Macro to the Micro Level and to the Spatial Dimension

For a long time, scholars have approached the analysis of inequality narrowly. Until recently, income was the only measurement scholars used to assess inequality and most studies focused on macro (country-level) analyses of inequality. However, macro indicators and national level analysis do not capture the lived experience of inequality. Empirical studies have shown that even when incomes become more equal on the national level, this does not necessarily mean that all people have equal access to opportunities and public services or that public resources are distributed fairly based on the needs of communities.

Multidimensional poverty and wealth measures have the potential to capture the real situation of people in more detail (Picketty, 2014; Stigltz, 2012). If we want to understand the causes and consequences of inequality and determine how fairly or unfairly resources are distributed, we must cast a wider measurement net.

Additionally, because most studies of inequality focus on the macro-level, the spatial dimensions of inequality within countries are still under-theorized. National-level data hide the often sharp variation between different localities. Research that has touched upon the spatial dimension of inequality in Egypt has focused largely on the dichotomy between urban and rural areas, in part due to Egypt’s history of land redistribution, but also due to theories about modernization’s role in development.

Due to the belief that urbanization and modernization would generate greater levels of equality, research tended to focus on the gaps between rural areas and urban areas, suggesting that rural areas are deprived of services, access to markets, and ‘voice’ compared to cities. However, cities all over the world continue to prove to be unfair for many of their citizens, creating deprivation that can be related to the location of the individual inside the city itself. The dynamic of inequality in Egyptian cities has been largely unexplored and more tailored, dynamic analysis is vital for understanding the scope, causes and consequences of urban inequality. Using tools of research and indicators on the micro level, we can focus and theorize about the interaction between individuals, communities, and public policy priorities and the impact of this interaction on inequality.

Governance, Spatial Injustice and Underserved Areas

Often, policy decisions create or encourage spatial inequality; however, the ways in which the government formulates policy decisions and allocates public funds to urban areas are not always clear-cut. Urban governance, “the linkages of people, organizations, regulations and practices – visible and hidden, intended and unintended,” creates formal and informal rules for decision-making which determine which areas get resources and which do not (Marwell, 2014).

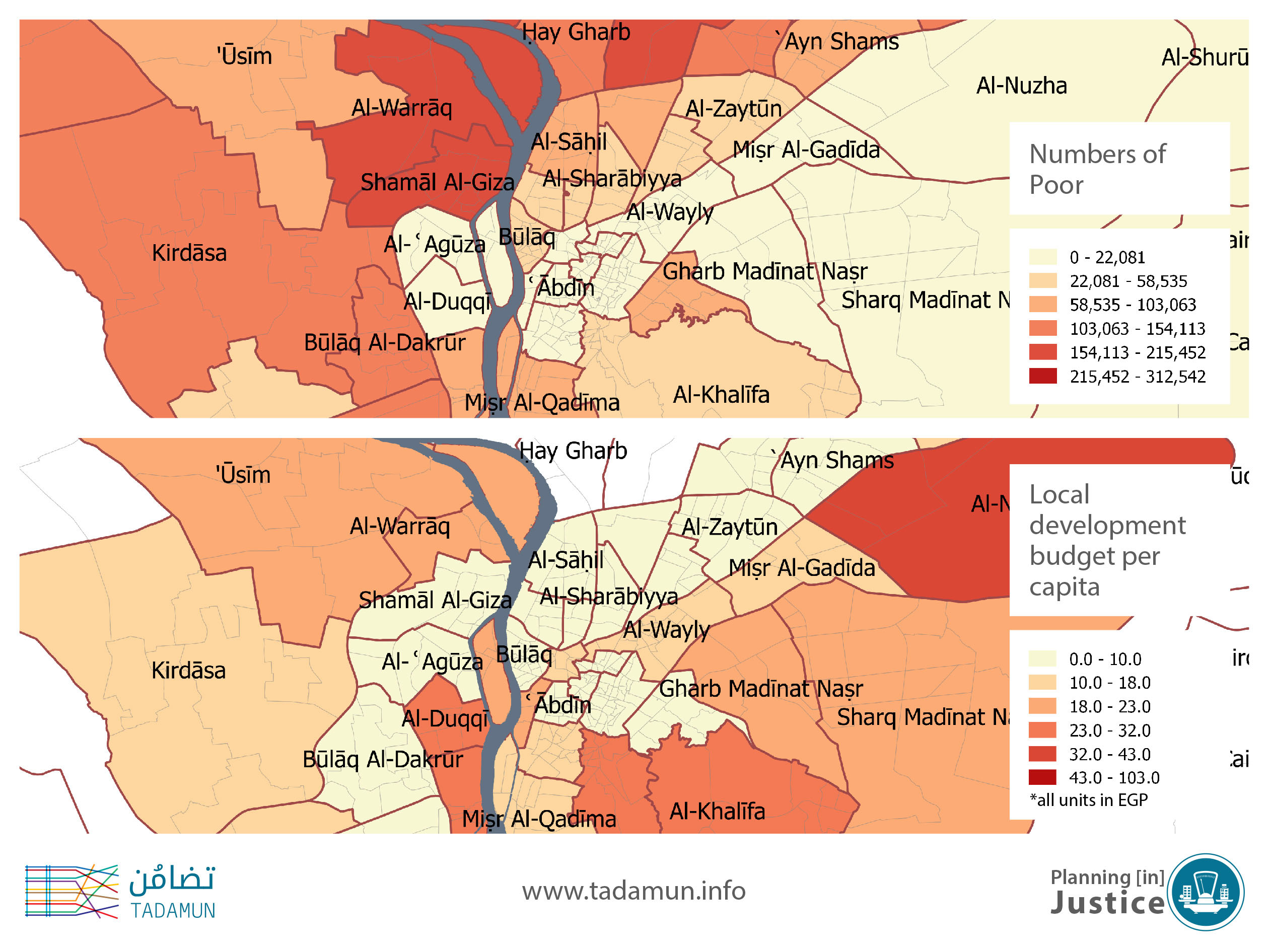

Decisions are not always made with an eye toward increasing a more just distribution of resources between geographic spaces. Within Egypt, for example, local development budgets should theoretically be distributed according to an equation that considers population size and area size – though it is not publically known how each factor is weighted. However, in reality, each local district has to request their budget officially from the provincial Governor and their success is often dependent on their political capital and bargaining power. Ultimately, whether the population/area equation is used or not, the government allocates budgets regardless of poverty levels or the needs of residents of each district, as can be seen in the figure below. The two maps reveal that the districts which absorb the highest amounts of the Local Development Funds per capita (which are very modest and finance paving, street lighting, environmental upgrading and other local needs from the Ministry of Local Administration) are not the districts where the highest numbers of poor people reside. In other words, there is a mismatch between local needs and the government’s allocation of local development budgets.

Governance is a process that can serve as an equalizing force, but governance can also increase the social and political production of inequality (Marwell, 2014). Through revealing the underlying power structures behind the social and political production of inequality, we can render spatial inequality “more publicly unjustifiable” and advocate for policies that aim to bring cities closer to the ideal of complete spatial equality and justice (Lobao and Saez, 2002, 503).

Poor targeting of services and programs is one way that urban governance might increase spatial inequality between areas and even create spatial poverty traps. One household may live in an area with higher average incomes, better infrastructure and better access to services and it may see its standard of living increase over time, while another household living in an area with lower average incomes, worse infrastructure and low quality or access to services can see its standard of living remain stagnant or decrease over time (Ravallion and Jalan, 1997, 2).

The household located in the deprived area experiences the challenges of a spatial poverty trap. Access to basic services helps generate income, which in time, could help households overcome poverty and increase spatial equality between geographic areas. For example, children living in deprived areas often have access to fewer, over-crowded, and lower-quality schools, which decreases their future chances of moving beyond poverty (for further information see Tadamun’s, “Inequality and Underserved Areas: A Spatial Analysis of Access to Public Schools in the Greater Cairo Region.” If public investment is not targeted to areas with the greatest need for infrastructure, services, and job opportunities, those areas will be unable to climb out of poverty and the standard of living will remain stagnant (in the best case scenario) or decrease over time.

Data is Power in the Fight for a Decent City for All

New research investigating the scope and causes of spatial inequality in some nations is beginning to assess how incomes, access to services and the quality of these services vary across space at the micro-level, often down to the city block. This new research agenda has revealed troubling geographic discrepancies in poverty, income inequality, health outcomes, educational attainments, as well as the quality of, and access to, services within cities in developed and developing countries alike. Since micro-level data on spatial inequality in developed countries is often publicly available and accessible to researchers, communities and activists can find the tools and data to understand where they stand in relation to neighboring areas and advocate for better policies and greater equality.

An example of these analytic tools is a visualization of census-tract level data of the percentage of people living below the poverty line in the New York City area, drawn from the 2008-2012 U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. Each shaded area on the map represents a census-tract (containing an average of 4,000 people). In the darkest shaded areas, 40% of people or more live below the poverty line. The lightest shades represent areas where less than 10% of the population lives below the poverty line. In some places on the map, neighborhoods with low levels of poverty are directly next to neighborhoods with high levels of poverty.

Source: Matthew Bloch, Matthew Ericson, and Tom Giratikanon, The New York Times. “Mapping Poverty in America: Data from the Census Bureau Show Where the Poor Live.” January 4, 2014.

Maps like this allow us to easily see the extent of the geographic concentration of poverty and spatial inequality for a given region at a very local level. Ready-made maps for all of the major U.S. cities are available and the full American Community Survey is accessible if one wanted to look at spatial inequality in any other region in the United States. As a result, if you are a policy-maker, non-profit organization, movement activist, or a concerned citizen who wants to know which neighborhoods would benefit the most from poverty-alleviation programs and services, or how people can organize to change their situation, the data is often right at your fingertips. Compelling data analysis does not necessarily lead to more equitable policies but evidence-based research behind persuasive arguments can sometimes mobilize aggrieved constituencies to act, or even mobilize champions of change within government and policy circles.

Unfortunately, micro-level data on poverty, inequality, and service provision has been less accessible in Egypt which inhibits the effective targeting of programs and services and masks the problems some neighborhoods face, largely on their own. Many scholars and government institutions have studied poverty and inequality in Egypt, but most studies have focused on the macroeconomic causes of inequality rather than the analysis of inequality at the municipal level.2 Until 2010, almost all studies of inequality in Egypt focused only on income inequality (Al Shawarby, 2014, 15). More recently, work is beginning to explore how service provision, policies, and governance vary across space, creating and perpetuating inequality.3 The pervasive problem of rural poverty in Egypt has motivated extremely nuanced data collection and analysis on service provision at a very local level to determine its causes and the consequences of rural inequality (See El Tawila et al, 2014).

However, the bulk of studies on service provision in Egypt remain at the governorate level, which may disguise the scope of spatial inequalities at the local level, particularly in urban areas where inequality is high. In fact, Cairo has a higher level of inequality than any other governorate in the country (Milanovic, 2013). The observed levels of inequality in Cairo demand deeper analysis at a localized level to determine how income, living standards, service provision and governance may vary across space, creating pockets of poverty in certain areas but not others.

The TADAMUN initiative aims to reveal the scope of spatial injustice stemming from current policies, older legacies of flawed urban planning, as well as the uneven allocation of public goods and services. A number of important questions guide our research and will be addressed in our project’s forthcoming publications and tools of analysis. Why are some neighborhoods consistently underserved, and how we can develop a plan of action to move toward greater spatial justice? How does urban governance and public policy vary across space in ways that privileges some areas while neglecting others? How have residents navigated the formal and informal rules of urban decision-making to get the services they need? How are the decisions of where to allocate public funds made and who can be held accountable for areas that have been historically neglected? Most importantly, how can our research help direct public and private initiatives to improve services and reduce inequality in the most challenged neighborhoods?

But before we can unravel the causes and consequences of inequality, we must first understand the extent of the problem. Thus, our Planning [in] Justice initiative aims to collect and analyze data in order to increase public awareness regarding the absence of spatial justice in the distribution of public resources between urban neighborhoods. In pursuing this objective, the project will publish research and develop tools to identify, measure, and address these inequalities.

The project attempts to understand and address issues of spatial injustice from a “Right to Adequate Housing” perspective and to measure the government’s fulfillment of its component parts, including legal security of tenure, availability of services, facilities, and infrastructure, affordability, habitability, accessibility, location, and cultural adequacy.4 The comprehensiveness of the Right to Adequate Housing, from our view, is a better tool to understand the actual needs of residents and to achieve an acceptable level of quality of life across the GCR’s different neighborhoods. Measuring the levels of fulfillment of each aspect of the right to adequate housing at the neighborhood level will provide a new interpretive lens to understand the Greater Cairo Region (GCR).

One of the main tools we use to analyze and visualize spatial inequalities from this perspective is GIS (Geographic Information Systems). GIS allows us to visualize the distribution of poverty, services, and investment geographically and to spot deprived neighborhoods. Using GIS capabilities, the Planning [in] Justice project will produce a set of maps of various indicators of spatial inequality, which allows for the visualization of the variation in poverty, resources, services, and public investment between urban neighborhoods in the GCR. Most of these maps will be illustrated at the shiyakha level to capture levels of inequality within the GCR in a more detailed manner.

The Planning [in] Justice project will disseminate its forthcoming results to decision makers so that they are better informed about the existing development gaps and levels of deprivation in the GCR’s different neighborhoods. This will provide them with the necessary tools to develop more effective policies and programs to target these gaps and depravation levels. On the other hand, the project will also provide the public with relevant data and maps on urban injustice on the GCR level so that they have a better idea of where their neighborhood stands, and can demand their rights.

A particular benefit of our project is that we largely use publically available data and open source software. This means that the public can adopt or adapt our project methodologies to address other aspects of inequality that matter to them or conduct similar research in other areas of Egypt. By making this data and these tools available, other active groups in Egypt can assess neighborhood needs, and advocate for a more just distribution of public funds.

Conclusion

TADAMUN’s localized approach seeks to understand spatial inequality within the GCR, using census data and other available data, while also mapping the levels of public investment and development in the same areas. Our project seeks to unravel the complexity of spatial inequality in the city, concentrating on the ways in which urban governance creates and perpetuates spatial inequalities between neighborhoods.

Many people in Cairo know that neighborhoods are not equal to each other, that some neighborhoods are wealthier and offer better services, while others have less. But until now, much of the data needed to represent the scope of the problem was scattered. By compiling and translating knowledge and data that was previously inaccessible, we offer a compelling way to question the fairness and logic of public investment and development strategies that favor wealthier area and ignore the poorest and most underserved districts.

By producing evidence-based research on the scope, causes, and consequences of spatial inequality, and mapping spatial inequality, we provide a tool for Cairenes to understand the character of their neighborhoods and the way that their city is managed. This tool is also available for policy-makers to measure the specific needs of individual neighborhoods and to target their policies and develop a more equitable and just match between needs and resources in Cairo.

TADAMUN imagines the decent city as a place where adequate housing, services, and basic needs are the right of all Cairenes, rather than privileges afforded to some and not to others. By drawing attention to underserved areas, providing a means to assess the needs of communities within these areas and coming up with solutions to help narrow the gaps between neighborhoods, we are taking a first step towards making the decent city a reality for all.

References

Al-Shawarby, S. (2014). The Measurement of Inequality in the Arab Republic of Egypt: A Historical Survey. In P. Verme, B. Milanovic, S. Al-Shawarby, S. El Tawila, M. Gadallah & E.A.A. El-Majeed (Eds.), Inside Inequality in the Arab Republic of Egypt.: Facts and Perceptions Across People, Time and Space (pp. 13-35). World Bank, Washington, D.C.

Bloch, M., Ericson, M., & Giratikanon, T. (2014, January 4). Mapping Poverty in America. The New York Times.

Brixi, H.P., Lust, E., and Woolcock, M. (2015). Trust, Voice, and Incentives: Learning from Local Success Stories in Service Delivery in the Middle East and North Africa. World Bank Group, Washington D.C.

El Tawila, S., Gadallah, M. & El-Majeed, E.A.A. (2014). Poverty and Inequality in the Arab Republic of Egypt’s Poorest Villages. In P. Verme, B. Milanovic, S. Al-Shawarby, S. El Tawila, M. Gadallah & E.A.A. El-Majeed (Eds.), Inside Inequality in the Arab Republic of Egypt.: Facts and Perceptions Across People, Time and Space (pp. 101-124). World Bank, Washington, D.C.

Ravallion, M. and Jalan, J. (1997). Spatial Poverty Traps? World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 1862.

Lobao, L., and Saenz, R. (2002). Spatial Inequality and Diversity as an Emerging Research Area. Rural Sociology 67(4), pp. 497–511.

Marwell, N. (2014). Mapping the Social Geography of Inequality. The Social Science Research Council.

Milanovic, B. (2014). Spatial Inequality. In P. Verme, B. Milanovic, S. Al-Shawarby, S. El Tawila, M. Gadallah & E.A.A. El-Majeed (Eds.), Inside Inequality in the Arab Republic of Egypt.: Facts and Perceptions Across People, Time and Space (pp. 37-54). World Bank, Washington, D.C.

Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Harvard University Press

Shawkat, Y. (2013). Social Justice and the Built Environment: A Map of Egypt. The Right for Housing Initiative.

Stiglitz, J. (2012). The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

United Nations. (1991). The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. General Comment 4, The Right to Adequate Housing. E/1992/23, New York, 13 December.

Additional Resources

Abdelhaliem, R. (2014). Revisiting Growth and poverty Nexus in Egypt with reference to the World Bank Country Partnership Strategies,” Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights.

Abdelhaliem, R. and Diab, O. (2014) Budget Transparency: The Missing Economic Necessity in the Case of Egypt,” Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights.

Assaad, R. and Roushdi, R. Poverty and Geographic Targeting in Egypt: Evidence from a Poverty Mapping Exercise, Population Council in Egypt, Working Paper 0715.

1.The classification of an area as “unplanned” is based on the Unified Building Law no.119/2008, while the label “unsafe” is based on the classification of Egypt’s Informal Settlement Development Fund.

2.During the 1970s, most research focused on the impact of Nasser’s land reforms and how changes in land distribution altered the extreme inequalities that characterized the pre-Nasserist era. In the 1980s, scholars began to explore the spatial dimensions of inequality, focusing on the urban-rural divide. This strand was especially interested in how Sadat’s open-door policy exacerbated inequalities between regions, compared to the equalizing effects of Nasser’s land reforms. See Al Shawarby (2014) for a detailed review of historical studies of inequality in Egypt.

3.See Brixi, Lust & Woolcock 2015 for a detailed analysis of service delivery across the Middle East and North Africa.

4.United Nations. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. General Comment 4, The Right to Adequate Housing. E/1992/23, 13 December, 1991.

Comments