Mapping Dispossession in Turkey

Turkey’s Urban Renewal Projects

Networks of power and capital behind large-scale urban projects in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) largely remain out the purview of the public. The state holds data about urban development projects and often does not make this data publicly accessible. In Turkey, the government has undertaken a policy of urban renewal since the mid-2000s. In 2005, a new municipal law – Law No. 5366, The Law on Renovating, Conserving and Actively Using Dilapidated Historical and Cultural Immovable Assets – authorized municipalities and the TOKI (Mass Housing Administration of Turkey) to implement urban renewal in Turkey’s historic areas.[1] The law states that the government may “take measures against earthquake risk or to protect the historical and cultural structure of the city” (Kestler-D’Amours, 2014). This policy has predominantly impacted Istanbul and its 47 historic neighborhoods, in particular. The majority of neighborhoods with urban renewal projects are home to immigrant communities (like the Romani people of Sulukule, in Istanbul), high poverty rates, and informal housing with few safety standards to withstand natural disasters (Çevik, 2011). Turkey’s urban renewal policies (commonly known as “urban regeneration”) grant municipalities the authority to designate specific “renewal areas” for development into large-scale projects like airports, gated communities, shopping malls, luxury housing, and office buildings. These renewal areas are either historic area populated by the urban poor with restrictions on construction or squatter settlements (locally known as gecekondus) with high-value real estate (Turkun, 2011). More stringent policies and legislation resulted in construction limitations in gecekondus and historic areas, including for example the 2004 penal code which makes gecekondu construction punishable by law (Karaman, 2012).

In 2011, a major earthquake in eastern Turkey prompted the government to pass Law No. 6306 of 2012, commonly known as the Urban Regeneration Law. The law grants the Ministry of Environment and Urban Planning (MEUP) and the Turkish Prime Minister sole authority to demolish and renovate housing units that do not meet safety standards within ‘risk areas.’[2] The government defines ‘risk areas’ as areas or structures that could cause loss of life and property. Nearly 7-10 million housing units in Turkey do not currently meet earthquake safety standards and will undergo demolition and renovation (Özeke, 2012; Balamir, 2013; Candas, Flacke, & Yomgraliogolu, 2016). The Turkish government offers homeowners in homes slated for demolition compensation and offers loans for renters to move into new properties (Balamir, 2013). Other low-income families moved to TOKI public housing sites 30-50 km from their former neighborhoods and jobs, which burdened them with increased transportation expenses. Nevertheless, residents, especially poorer residents, continually experience forced evictions and displacement.

Local activists, scholars, and residents in Turkey called into question the impact of these laws, arguing that they serve as a pretext for evictions to benefit the previously declining real estate and construction sectors. They also took issue with the unclear definition of ‘risk areas’ under Law No. 6306, and the absence of any citizen participation in the projects (Balamir, 2013; Tarakçı & Özkan, 2015). Much of the ongoing urban renewal projects transformed historic neighborhoods into business centers, airports, gated communities, shopping malls, and luxury housing. For example, from 2007 to 2010, the Istanbul municipality forcibly evicted nearly 5,000 families in Sulukule, a historic Istanbul neighborhood inhabited by Romani people for thousands of years, to construct “Ottoman style” housing developments (Young, 2011).[3]

Since information about the relationships behind Turkey’s urban projects remains murky, a network of volunteer activists, artists, journalists, lawyers, and urbanists decided to create a publicly-available mapping platform following the 2013 Taksim Gezi Park demonstrations which erupted when the government tried to replace a public park with a new shopping mall. The Networks of Dispossession Project (NOD) studies the relationships between public and private sector actors involved in urban mega-projects. NOD uses a network mapping platform to create clear visualizations of these relationships of power and capital. It also documents the government-seized properties in Istanbul. As an on-going project, NOD educates the public about the mega-projects and stimulates public dialogue among impacted residents and urban activists.

NOD emerged out of the Gezi Park demonstrations and developed into a mapping platform to draw attention to imminent large-scale development projects. In this brief, Tadamun examines how NOD uncovered public-private partnerships that dispossess urban residents, calling into question the equal rights of all Turkey’s people to shape and reside in the country’s urban spaces.

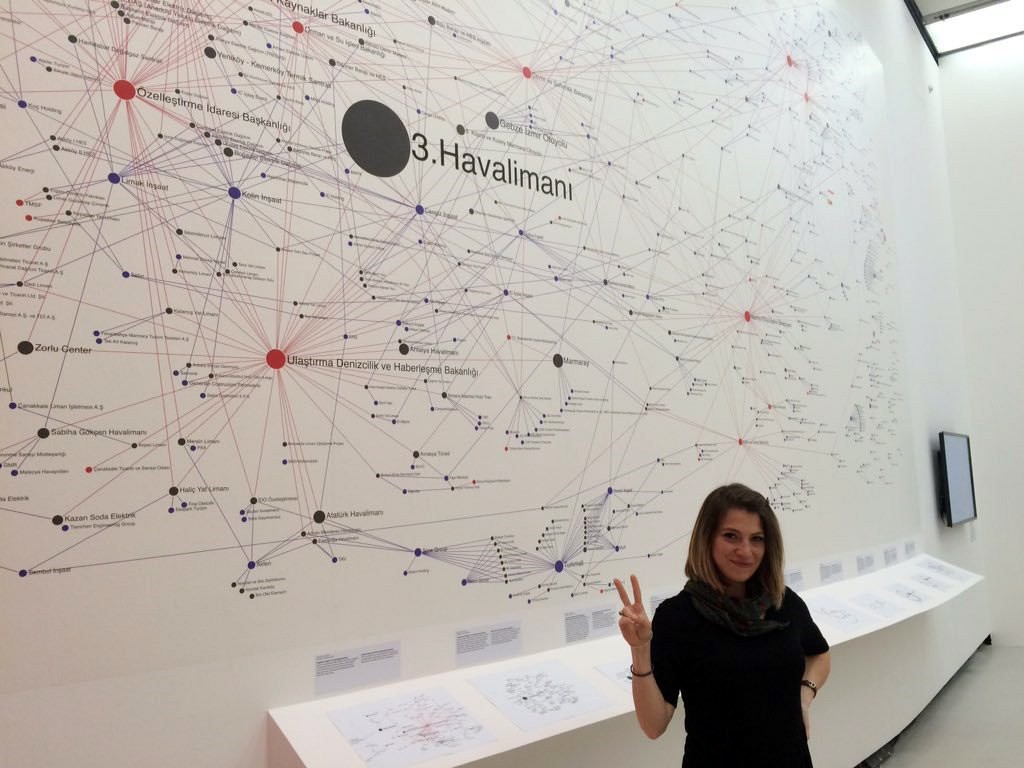

Figure 1: Networks of Dispossession displaying their maps at the MAXXI Museum “Istanbul. Passion, Joy, Fury” Exhibition in 2015-2016. Source: Networks of Dispossession

Conceptualizing Dispossession

Following the 2013 Gezi Park demonstrations, a small group of volunteer activists, urbanists, artists, journalists, lawyers, and investment company employees who participated in the demonstrations began to pose questions about the impact of imminent mega-projects on Turkey’s urban future: What kind of projects dispossess residents in Istanbul and Turkey? Who are the actors involved in these mega-projects? What kind of public-private partnerships support these urban transformation projects?

The group created the Networks of Dispossession (NOD) project and began collecting information and data about urban transformation projects, their developers, and their impact on public space and urban residents. NOD uses data and information from public records including corporations’ web pages, newspaper articles, and government databases (Gribat, 2015). NOD’s definition of “dispossession” is broad, taking into account not only the physical displacement of urban residents but also labor-related deaths during the demolition and construction processes, as well as projects’ environmental impact. For example, NOD argues that the third Bosphorus bridge project, which opened in August 2016, will demolish Istanbul’s last forest areas and negatively impact water reservoirs.

In 2013, NOD first created its database to identify developers involved with the redevelopment plan of Gezi Park. NOD’s contributors then pieced together information from public records to show how the same developers involved in Gezi Park were contracted in several other projects in Istanbul. They gradually added information on a variety of public and private sector actors involved in urban redevelopment projects and the impact of those projects on Turkey’s urban residents and public spaces. NOD volunteers then used this data to map the intricate networks of power and capital using an interactive network mapping software—Graph Commons. Their publicly accessible network maps are an important tool for activists, urbanists, advocates, academics, journalists, residents, and anyone else interested in the transformation of urban life and urban landscapes.

NOD consists of three main map categories to document dispossession in Turkey:

- Projects of Dispossession unveils mega-projects and partnerships between public institutions and corporations. Projects include the Istanbul airport project and loss of urban space; shopping mall plans that displace residents in the Istanbul neighborhoods Tarlabasi and Sulukule; and the Grand Pera Project (shopping mall) which was set to demolish the historic Emek Theater in Istanbul, among others.

- Partnerships of Dispossession uncovers how private and public actors share power on executive boards of companies responsible for developing the mega-projects.

- Dispossessed Minorities shows both urban contemporary dispossession and government confiscation of property previously owned by non-Muslim minorities in Turkey, such as Armenian and Greek communities. The map shows which properties have been seized, the communities that previously owned the properties, and the state institutions or private companies that have taken ownership. Turkey has a law that allows for minority communities to reclaim seized properties but this law does not take into account properties that may have been demolished or communities that may have migrated (Gribat, 2015). Nevertheless, the map allows communities to trace the seized property’s history and its reclamation over time.

NOD’s Impact

Much like other MENA states, the Turkish state withheld data on urban projects from the public, thereby diminishing the power of local grassroots efforts to analyze data and mobilize citizens on critical issues facing the future of their cities. The project serves as an “urban watchdog.” Throughout Turkey and especially in Istanbul, NOD provides activists, urbanists, academics and the public access to information about the urban mega-projects—an important tool for advocating greater transparency and participatory planning in the urban transformation process.

NOD disseminated and publicized its work by participating in the 2013 Istanbul Biennial—an exhibition in the visual arts field held every two years. Their participation in the Biennial exposed their work to a broader public, both national media outlets and other constituencies throughout Turkey such as journalists, academics, activists, and artists. Different communities have interpreted and used NOD’s maps to serve a diverse range of purposes and applications. For example, academics used NOD’s work in research projects, artists saw the maps as a groundbreaking piece of visual art, activists considered NOD’s efforts an act of resistance, and journalists promoted the data in news articles (Golonu, 2015). Groups like Isci Guvenligi (Worker Safety) that monitor labor-related deaths and Diren Cevre (Environmental Resistance), a group at Bogazici University that create maps tracking ecological corruption in Turkey, collaborated and expanded NOD’s work (Golonu, 2015). Consequently, NOD used data provided by Isci Guvenligi to create a map tracking labor-related deaths during the construction of mega-projects like the $200 billion third Bosphorus bridge in Istanbul, which opened in late 2016. Furthermore, NOD added the “Dispossession of Minorities” map using property records provided by Armenian churches after the Turkish state seized their properties several decades ago.

Given the nature of their work, NOD also assumed the role of an urban mapping watchdog. Several opposition members of the Turkish government communicated with NOD founders to investigate corruption allegations surrounding developers contracted for several urban mega-projects. Opposition members shared the maps among their professional circles and provided important information about other ongoing projects for NOD activists to use (Golonu, 2015). The maps also issued an implicit warning to developers and architects that their firms and companies can be held accountable and their partnerships revealed (Gribat, 2015). Yaser Adanali, one of NOD’s founders, explains that architects involved with these projects started to inform their colleagues: “you can be there [on the map], watch out” (Golonu, 2015).

Networks of Dispossession stands out as a unique project. NOD takes mapping beyond its traditional use to delineate the complex relationships between power and capital underlying major real estate, construction, industrial, and infrastructure projects. By allowing the public to map relationships and actors on the aforementioned projects using the Graph Commons software themselves, NOD serves as a collaborative tool that illuminates urban transformations in Turkey. The project facilitates analysis by dispossessed residents and activists themselves. NOD flourishes the more the public interacts and adds information to its database and maps. NOD is an invaluable source of knowledge, not only on the relationships between different actors involved in urban transformation but also on different zoning regulations and planning provisions throughout Istanbul municipalities.

This provides residents and activists the tools to initiate collaboration and to mobilize. For example, Armenian churches reached out to NOD to share maps and information about government-seized Armenian properties. The “Dispossessed Minorities Map” provided a platform for Armenian churches to mobilize for property reclamation through a law which allows minorities to reclaim seized properties. Furthermore, NOD engages in local knowledge production about dispossession for activists, urbanists, and the public. This local production of knowledge highlights the role of activists in bridging academic and technical knowledge together to benefit the public. NOD educates the public and challenges limitations on the right to information.

For urbanists and activists throughout the region, NOD offers an example of how to confront the negative impacts of large-scale urban development projects through mapping. They have provided a platform and built relationships to deepen activist tools and strategies. Information does not mean change will occur, but it may help people mobilize by finding common interests and collaborators while improving the chance of holding public officials accountable. Tadamun’s Mapping Urbanism project has highlighted NOD because it is an excellent example of the concrete ways that urbanist organizations and initiatives across the Middle East and North Africa are working to build just, equitable, and sustainable cities.

Works Cited

Balamir, M. (2013). Obstacles in the adoption of international DRR policies: The case of Turkey. Background paper prepared for the global assessment report on disaster risk reduction, 2-24.

Candas, E., Flacke, J., & Yomralioglu, T. (2016). UNDERSTANDING URBAN REGENERATION IN TURKEY. International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing & Spatial Information Sciences, 41.

Karaman, O. (2013). Urban renewal in Istanbul: Reconfigured spaces, robotic lives. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(2), 715-733.

Kestler-D’Amours, J. (2014, April 19). Turkey braces for next major earthquake. Al Jazeera. Retrieved from http://www.aljazeera.com/news/middleeast/2014/03/turkey-braces-next-major-earthquake-201431182932518813.html

Özeke, H. (2012, December 11). Turkey: The Biggest Construction Site On Earth: Turkey What To Expect From The Urban Regeneration Law. Mondaq. Retrieved from http://www.mondaq.com/turkey/x/210906/Building Construction/The Biggest Construction Site On Earth Turkey What To Expect From The Urban Regeneration Law

Tarakçı, S., & Özkan, A. (2015). Evaluation of Law no. 6306 on Transformation of Areas under Disaster Risk from Perspective of Public Spaces – Gezi Park Case. Iconarp International Journal of Architecture and Planning, 3(1), 63-82. Retrieved from http://iconarp.selcuk.edu.tr/iconarp/article/view/35/66

Türkün, A. (2011). Urban regeneration and hegemonic power relationships. International planning studies, 16(1), 61-72.

Young, M. (2011, April 25). The Face of Urban Renewal and Preservation in Istanbul. Untapped Cities. Retrieved from http://untappedcities.com/2011/04/25/the-face-of-urban-renewal-and-preservation-in-istanbul/

Published Interviews:

Golonu, B. (2015). [Interview with Burak Arikan, founder of Graph Commons and NOD activist]. Open Systems. Retrieved from http://www.openspace-zkp.org/2013/en/journal.php?j=7&t=46

Gribat, N. (2015). [Interview with Yasar Adanali, one of NOD founders]. Sub/Urban Magazine, 3, 153-164. Retrieved from http://www.zeitschrift-suburban.de/sys/index.php/suburban/article/view/169/294

Websites:

Networks of Dispossession. (2013) Networks of Dispossession Information. Retrieved from https://burak-arikan.com/networks-of-dispossession/

Networks of Dispossession. (2014) Networks of Dispossession Version II: Collective data compiling and mapping on the relations of power and capital. Retrieved from https://blog.graphcommons.com/networks-of-dispossession-version-ii/

[1] A government institution founded in 1984, TOKI reports to the Office of the Prime Minister and has the authority to develop and modify zoning plans and is responsible for the finances of urban renewal projects.

[2] MEUP has the right to designate risk areas; permit local authorities to determine risk areas in their municipality; expropriate property; develop plans and build. Property owners are given a 30-day evacuation notice and any objections by citizens are made to local administrations, not to the courts (Balamir, 2013). Following redevelopment of property, citizens are offered compensation or long-term loan program. Citizen comments and opinions during or after the redevelopment phase are not permitted. For a detailed step-by-step analysis of the Urban Regeneration Law and case studies, see: Candas, Flacke, & Yomgraliogolu, 2016.

[3] Read about Sulukule’s history and the impact of renewal in the 2008 Sulukule UNESCO report.

Comments