Mapping MENA Urbanism: An Introduction

Introduction

As cities across the Middle East and North Africa confront the challenges of urbanization, a growing dynamism of urbanist voices offers new and alternative visions of how we should plan, build, manage, and live in cities. From grassroots community-based organizations to professional associations, academic researchers, and activists, MENA urbanists are designing and implementing new and innovative strategies for solving pressing urban development challenges and working to improve daily life in the cities in which they live. A decline in public services; a lack of affordable, adequate housing and soaring land prices; growing informality; rising inequality—these are some of the common and interrelated problems that persist in cities throughout the region. Such challenges are certainly not unique to the Middle East and North Africa, but MENA cities face similar obstacles and resistance to resolving them. The right to the city in the MENA region has long been confined to a small political and economic elite, who have the power and resources to shape the built environment (Bageen 2009). [1] Today, an expanding group of MENA urbanists are becoming increasingly visible and promoting an agenda to make cities more inclusive and their planning and management more participatory—asserting that the right to the city belongs to all citizens, not just a privileged few. However, their efforts remain largely unconnected and there is enormous potential for enhanced cooperation and collaboration among MENA urbanists. The activities of MENA urbanists are also under-reported and there is no single platform—a website, database, or other such formats—hosting information on these organizations, initiatives, and individuals. Therefore, it is not only difficult for outside observers to learn about how MENA publics and professionals are putting forth new visions for ordering public space, but it is also difficult for those organizations and individuals to learn about and from each other.

In other parts of the world, urbanists and engaged citizen groups have strengthened their work on creating sustainable, inclusive, and livable cities by coming together under a common agenda. In 2016, Tadamun staff and researchers traveled to Quito, Ecuador for the United Nations Habitat III Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development. We encountered a number of urbanist coalitions who had formed networks to combine efforts around a variety of urban issues. The Global Platform for the Right to the City (GPR2C), for example, is a group of over 100 organizations, predominantly focused on Latin America but also representing Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Europe, that came together in 2014 with the stated objective of encouraging governments to adopt commitments and policies aimed at developing fair, democratic, sustainable, and inclusive cities. In the year leading up to Habitat III, GPR2C members mobilized to successfully lobby the United Nations to include language on a comprehensive right to the city in the New Urban Agenda—the Habitat III outcome document. [2] The efforts of GPR2C around the New Urban Agenda are particularly illustrative of the importance and effectiveness of networks and combined efforts towards achieving shared objectives. We observed, however, both at Habitat III and in our daily work, that coalitions and networks among urbanists in the MENA are very rare, compared to other regional contexts. Moreover, we observed that MENA urbanists were severely underrepresented at Habitat III, and that the majority of the dialogue on MENA urbanism is dominated by public sector actors—governments and their contractors. When governments are the only parties with a voice in major international policy processes and their outcome agendas, like the New Urban Agenda or the Sustainable Development Goals, we see a disconnect between the resulting policies and efforts (and where resources are directed), and the reality of urban challenges and experiences.

Tadamun has launched this Mapping Urbanism project to create a space in which MENA urbanists can learn about interesting initiatives or projects others are undertaking in their own communities, other cities, and other countries, and also submit information to showcase their own work. There is much to be gained by strengthening ties among MENA urbanists: methodologies, strategies, and experiences shared between urbanists in the MENA will create more opportunities for dialogue to reach feasible solutions to shared urban challenges. That MENA urbanists face similar difficulties in their daily work—limited public access to information in many MENA countries and varying degrees of political openness—makes increased connectedness among MENA urbanists even more critical. There is also much to be gained by gathering information on MENA urbanism in one place, to create a more complete picture of similarities, variations, and differences country-to-country. We believe that there is as much to learn by examining the multiplicity of different ways urban challenges manifest in different contexts and the diversity of urban initiatives those differences give rise to as there is to learn from examining the commonalities.

Tadamun’s Mapping Urbanism Project

Tadamun’s Mapping Urbanism Platform explores the variety of perspectives, approaches, strategies, and institutional frameworks that MENA urbanists employ in their work. We are launching the Mapping Urbanism project to create and disseminate knowledge on the different ways MENA urbanists are responding to shared challenges, and also to highlight the many ways in which the experiences of MENA urbanists differ across the region. We hope that this project will serve as one step in a greater process to enhance regional cooperation and coordination among MENA urbanists around international development goals, building common agendas, shared approaches, and useful methodologies. We aim to create a common platform and space within which MENA urban initiatives can learn about each other, speak with a wider voice, share knowledge, and generally strengthen their efforts. By showcasing and supporting the work of MENA urbanists, we hope to encourage and facilitate increased connectedness and mobilization among these individuals and organizations and to create stronger institutional support for urbanist work in the region.

Mapping Urbanism has four main components: a database of MENA urbanist organizations, an interactive online map tool, case studies, and analysis of highlighted organizations and initiatives, and regional workshops. Tadamun researchers began compiling information for the database in 2016. It is designed to grow and be collaborative, and we have already identified and researched over 250 MENA entities dedicated to urbanist research; urban public policy; arts and culture; architecture; urban design and planning; local governance and the built environment; heritage; housing rights; and other related activities operating in 13 countries (Algeria, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tunisia, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates). We are developing the database into a user-friendly, interactive, and searchable map tool, which allows the exploration of initiatives by subject area focus, geographic location, size, and institutional structure. Tadamun will continue to build on this information to analyze shared regional urbanist priorities and concerns, as well as to highlight and document the work of individual initiatives. Perhaps the most useful component of our map tool will be that it is collaborative. It will not only be a platform for Tadamun to publish information on MENA initiatives, but also a space for individual website visitors to submit and share information about interesting and relevant work. In this sense, it will help individuals and organizations spread information about their own work.

Beginning in 2018, Tadamun plans to organize a number of regional workshops in various MENA cities to bring together and strengthen dialogue among urbanist entities—citizens, academics, architects, heritage conservation specialists, and others working on urban issues in the MENA region. These workshops will focus on particular themes relevant to urbanist work in the region including the housing; spatial inequality; public service provision; municipal policies to accommodate recent flows of refugees and migrants and their right to adequate housing; local governance; and the Sustainable Development Goals and the New Urban Agenda. Regional workshops can be an effective vehicle through which activists and organizations develop collaborative projects across a variety of issue areas, and it is our hope that these workshops will serve to develop a support network and common platform for MENA urbanists to collaborate on strategies to continue their work in the face of shared economic, security, and environmental challenges.

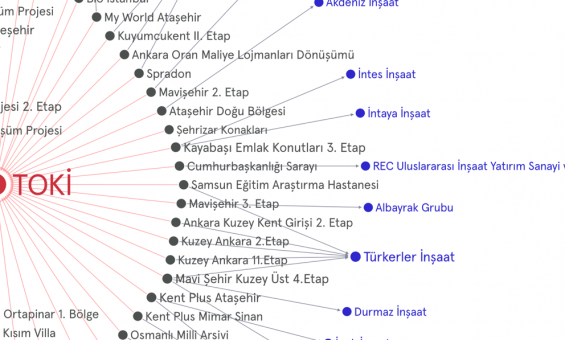

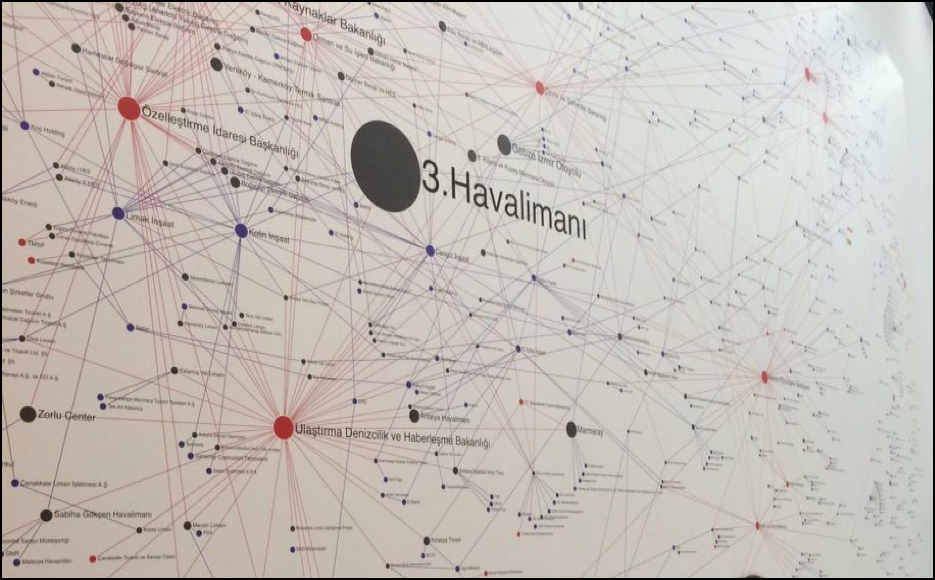

Figure 1: Graph depicting Turkey’s Housing Administration (TOKI) Contractors. Source: NOD (2014).

MENA Urbanism: Tackling Shared Challenges

That we see the same patterns of urban problems arising in MENA cities owes partly to the legacy of urban planning and land management norms there as well as pervasive shared governance issues across the region. As part of Tadamun’s broader mission, we strive to understand and reveal not only existing urban inequalities and injustices, but also their origins, larger dynamics, and the complexity of contributing social, economic, and political forces and actors. We also are very interested in current and future policies which may provide solutions to these challenges. Urban planning and land management are often approached as purely technical or managerial endeavors in the region—simple questions of resources and expertise, but we know this to be false. It is impossible to disentangle the building and maintenance of cities from instruments of power, domination, history, and social control. As we examine the shape and scope of MENA urbanism, it is important to understand it in the context of the long-standing and heavily entrenched planning institutions and practices, and the expressions of state power in which they are bound.

Ineffective, inappropriate, speculative, and outdated urban development institutions, policies, and practices persist in MENA cities, despite their demonstrated failure to solve pressing urban challenges. Poor planning practices continue not simply because states are poorly informed, under-resourced, or otherwise inept (though this is certainly the case in some instances), but because established planning structures and practices often serve the interests of powerful actors, both within the state and outside of it. The prevailing planning systems in MENA countries largely follow the same principles as the early modernist approach (Walton 2009; Flyvbjerg, Bruzelius, & Rothengatter 2003; Sheppard et al., 2015), which is poorly suited to the conditions and contexts of MENA cities today and has often been applied as a tool to distort space in favor of certain groups, at the expense of others (as discussed later in this brief). Developed in Europe and the United States during the early 20th century, the urban modernist approach promotes a particular vision of the ‘good city,’ in which “urban form is shaped by a concern with aesthetics (order, harmony, formality, and symmetry); efficiency (functional specialization of areas and movement, and the free flow of traffic); and modernization (slum removal, vertical or tower buildings, connectivity, plentiful open green space)” (Walton 2009, 2261). Urban modernism has been subject to criticism since its inception, even within nations where it served as the model. As early as the early 20th century, “it was noted that the supposed ‘public good’ objective of planning had been turned into a tool by the wealthy to protect their property values and to exclude the poor” (Walton 2009, 2261). Middle and commercial classes were able to use master planning and zoning—two of urban modernism’s most ubiquitous practices—to promote urban modernist ideals as a way of maintaining land values and preventing the invasion of lower-income residents, ethnic or racial minorities, and traders (Walton 2009). Still today, states and political and social elites across the Middle East (and elsewhere) support and execute urban development agendas, using tools like master planning and zoning, to promote their own economic and political interests, and shape the built environment to suit particular social, political, or ideological aims, through the language of urban modernism, and more recently, neoliberalism and globalization.

Globalization, in particular, globalized neoliberalism, impacts urban planning norms and practices in the MENA. It has imbued the dominant, globalized conception of ideal cities with an emphasis on free-market mechanisms as drivers of sustainable growth and development: privatization, economic liberalization, and deregulation (Bagaeen 2016). As such, the workings of the market and real estate industries increasingly shape urban space in cities everywhere (Walton 2009). States seeking to compete in the global market look to real estate development as a ubiquitous vehicle for economic development and invest in large-scale urban projects to build cities (often from scratch) designed to appeal to international investors, and which conform to globalized notions of what a modern, prosperous city should look like.

Additionally, large-scale urban projects are often closely intertwined with nationalist discourse and state efforts to demonstrate legitimacy, both to domestic and international audiences. Governments regularly make use of planning policies and institutions to construct an image of the state as more stable, secure, modern, and prosperous as a means of consolidating power (Bageen 2016, Deboulet & Fawaz 2011, Vale 2011). “A wide variety of regimes have used urban design and architecture to advance a nationalist agenda, and this “design politics” operates at all visible scales” (Vale 2011, 196). Certainly building and managing urban spaces is a political endeavor everywhere, but this is especially pronounced in contexts in which state authority is insecure or contested. “In those parts of the world where nation-states or their leaders are either weakened or continually challenged by violently opposing forces, social and political control of the city frequently becomes the stepping stone to securing power at the level of the region or nation” (Deboulet & Fawaz 2011, 3).

The result is a pattern of urban planning and development in which states funnel enormous amounts of capital into large-scale projects, guided by the principles of “the global intelligence corps and the internationalization of urban planning and design”—in effect, the expertise of a relatively small group of international planning, engineering, and architectural firms based in Europe and North America, regularly contracted to plan major urban projects in the Middle East (Bageen 2016). The problem is that most often, these projects are planned and executed without any serious discussion of their possible impact on the urban fabric in the areas in which they are located. The planning process is limited to developers, landowners, and their state backers, without comprehensive planning frameworks or avenues of participation available to other local stakeholders, elected representatives, community groups, and citizens. Consequently, major urban interventions are more likely to create negative unforeseen outcomes: land value inflation; unaffordable housing; displacement of lower and middle income urban residents; increased traffic congestion; or environmental degradation.

All of this is to say that MENA urbanists are not only tackling complex urban problems but are also often challenging established institutional structures and power systems, even contesting the very legitimacy of governments and their concern for the public good, at times. Another uniting factor among MENA urbanists (and a compelling reason for increased connectedness and cooperation between them) is that they must operate in countries still struggling with authoritarian governments. MENA urbanists must navigate complex political environments in their everyday work, whether they work in the non-profit, private, or public sector. If they criticize dominant planning paradigms their careers or reputations may suffer, leaving them cut off from the still sizeable government contracting, design, and architectural resources. MENA urbanism is anything but static or homogenous. In our research, we have found that a rich diversity of urbanists (both in the private and public sector) across the region are taking on a wide variety of institutional structures and strategies to tackle these complex, shared urban challenges, and confronting and navigating those institutions and actors that seek to govern urban life. Below, we explore the ways in which one of the most dominant modes of urban planning and development in the MENA—megaprojects and real estate-driven development—has inspired MENA urbanists to take action in three different national contexts.

Challenging megaprojects and real estate driven development

Throughout the Middle East and North Africa, the specter of real estate-driven urban development projects and mega-projects has given rise to urbanist work focused on anti-gentrification measures, coordinated street art campaigns, innovative mapping initiatives and other initiatives. Megaprojects proliferate across the region and take on different shapes and structures from country to country.

In Egypt, for example, New Urban Communities (NUCs)—government-constructed housing communities built on desert land—best exemplify the megaproject and real estate-driven mode of urban development. Tadamun has researched and written extensively on Egypt’s NUC’s (see our article “Egypt’s New Cities: Neither Just Nor Efficient”) and the many ways in which these land commodification processes benefit the few at the expense of the many. In 2015-2016, the Egyptian government invested EGP 33.2 billion into construction and development of new cities, which is almost four times the total public investment in the entire national education sector, and more than five times the total public investment in the health sector during the same years. As the government pours billions into sparsely populated new cities, living conditions in older cities where the bulk of Egypt’s population lives continue to suffer from inadequate funding and deteriorating services.

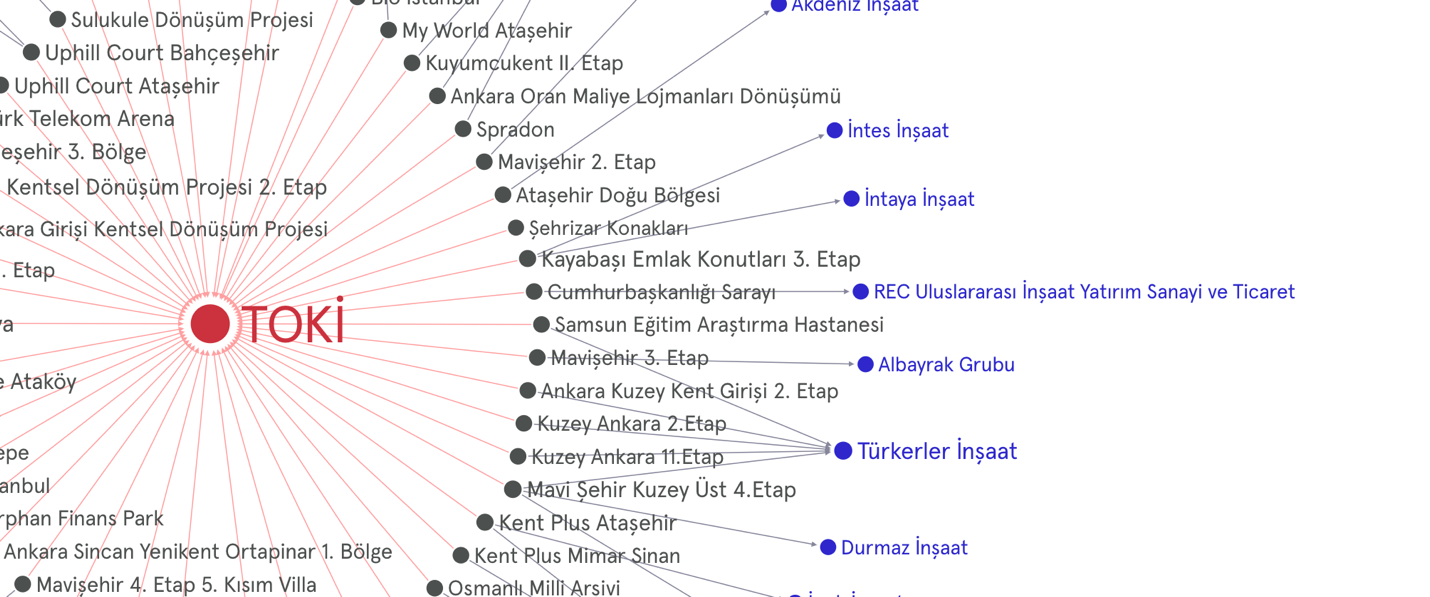

In Lebanon, we can also observe the effects of real estate-driven development in the redevelopment of downtown and waterfront Beirut and the resulting gentrification and privatization of previously publicly accessible spaces. Beginning in the mid-1990’s and following the destruction of much of the city during the civil war, Lebanon embarked upon a large-scale reconstruction of Beirut led largely by the construction and real estate industries. While such efforts have resulted in the rebuilding of many previously destroyed areas, they have also led to the effective privatization or pricing out of many areas previously accessible to the public. This is especially apparent along Beirut’s waterfront, where a proliferation of luxury resorts and condo complexes has made beachside areas largely accessible only to wealthy elites. In reaction to these developments, a multitude of urbanist organizations and initiatives in Lebanon, and Beirut in particular, have fought against and raised public awareness about the de facto privatization of public urban spaces. Dictaphone Group, for example, is a research and performance collective that produces multidisciplinary research on space and creates live art pieces as a means to comment on and re-imagine urban landscapes. In 2013, Dictaphone Group developed a performance piece titled “The Sea is Mine,” which explored land ownership of Beirut’s seafront, the laws governing it, and the practices of its users by inviting the audience to take part in a waterfront tour by fishing boat. As part of “The Sea is Mine,” Dictaphone Group also produced a booklet of the same title, which offered readers a well-researched, evidence-based overview of the privatization of Beirut’s coastal areas, its history, and the political and regulatory frameworks underlying it.

Figure 2: Participants in one of Dictaphone Group’s “The Sea is Mine” waterfront tours of Beirut. Source: Dictaphone Group (2013)

One area profiled in “The Sea is Mine” is Dalieh. For decades, Dalieh, a coastal peninsula that extends south of the Sakhret al-Raouche (Pigeon Rocks), has been one of the primary popular public spaces in Beirut. “A seaside open space, al-Daliyeh brings together a variety of social groups: Beiruti fishermen, patrons of the Rawsheh Corniche, residents of the suburbs, as well as members of the Iraqi, Syrian, and other communities residing in Beirut” (Dictaphone Group, 2013, 16). According to Dictaphone Group’s research of archival records, ownership of al-Daliyeh was historically confined to a few Lebanese families, but was zoned in a way that either prohibited or strictly limited construction to “sporting, leisure, and maritime facilities,” and was zoned for structural height limits (Dictaphone Group 2013, 16). In 1995, three real estate companies, including the late Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri’s Bahr Real Estate Company, purchased the bulk of plots in the area. Dictaphone Group argued that this change in ownership was “the first step in the effective undermining of this [al-Daliyeh’s] communal function and its transformation into a private interest.” A report detailing plans for developing al-Daliyeh into a private seaside luxury resort was released in 2014, spurring another kind of urbanist initiative: The Civil Campaign to Protect Daliyah of Rawsheh (CCPDR).

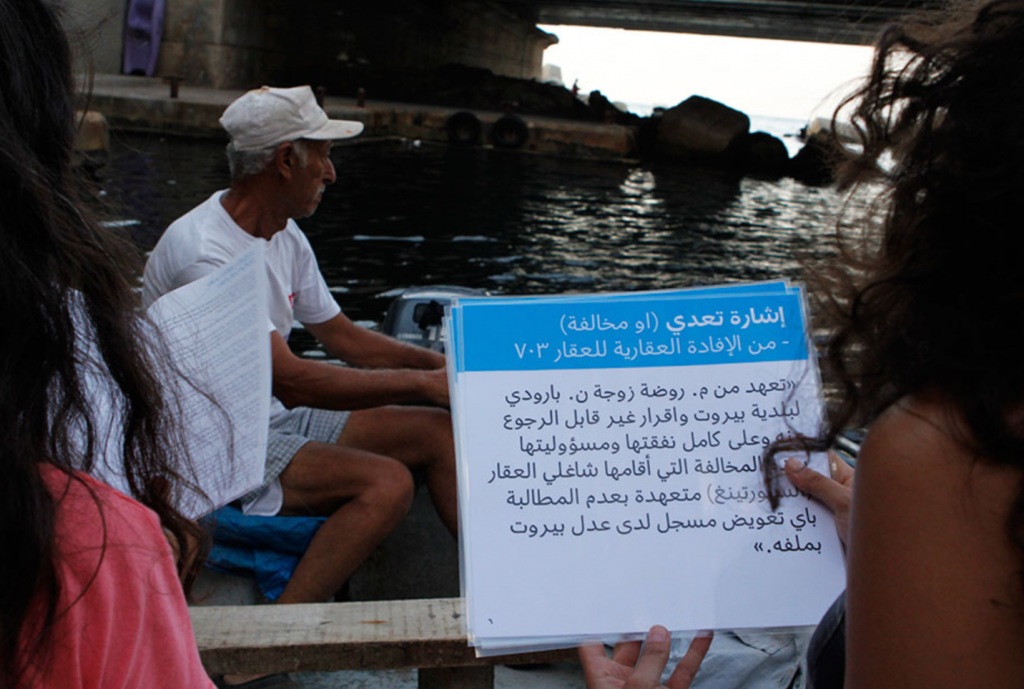

CCPDR is an all-volunteer coalition of residents, activists, architects, legal experts, and environmental justice organizations (of which Dictaphone Group is a member), which mobilized local and international media outlets, universities, and legal organizations to spread awareness about the potential negative economic, cultural, and ecological impacts of construction of a luxury resort. They produced a thoroughly-researched informational booklet on the history, biodiversity, topography, and socio-cultural significance of al-Daliyeh, as well as a timeline of events, demonstrations, and other forms of direct action to protect the area. CCPDR organized several demonstrations, including “An Encounter to Reclaim Public Space” in protest of a 377-meter barbed wire fence installed by private investors to limit public access to the beaches of Daliyeh. The Campaign also employed a participatory planning through its “Ideas Competition,” which urged urban designers, urban planners, architects, and residents to imagine and present alternative plans for al-Daliyeh. CCPDR filed a lawsuit against these plans and soon the Ministry of Environment decree designated al-Daliyeh a national protected area, and stipulated that any construction on Lebanon’s shoreline needed an approved environmental impact assessment.

Figure 3: An infographic CCPDR created depicting the various uses of al-Daliyeh. Source: CCPDR (2014).

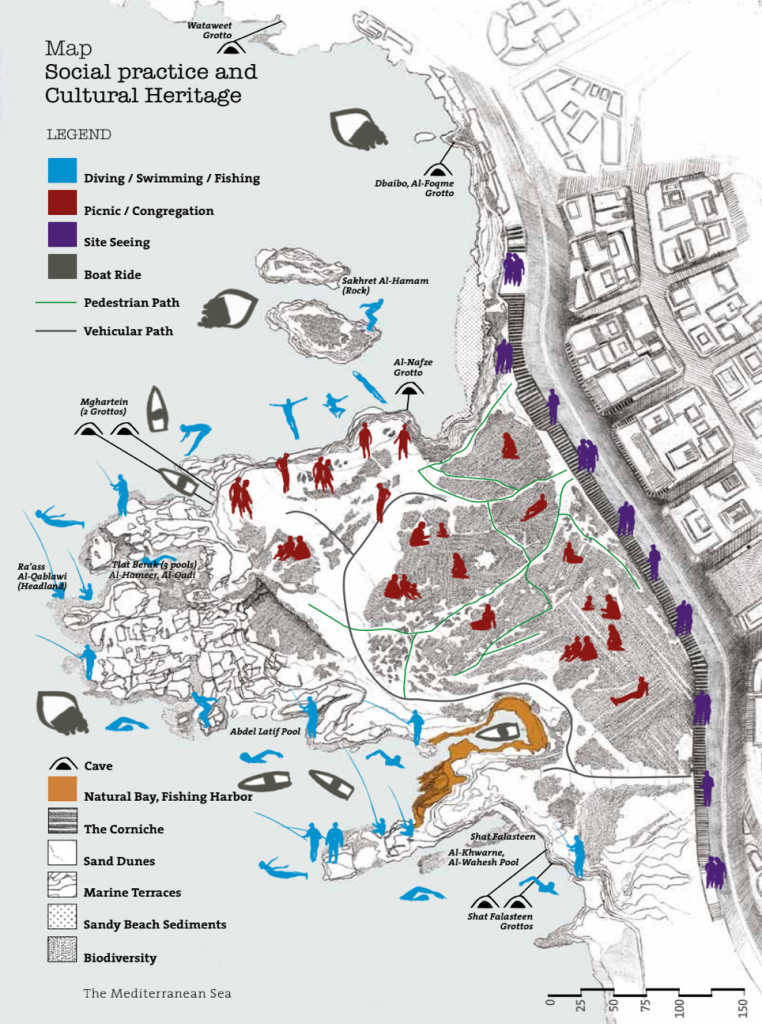

Megaprojects and real estate-led development in Turkey have also resulted in the privatization of previously publicly-accessible public spaces, as well as the displacement and dispossession of lower income and immigrant communities. Since the mid-2000s, Turkey has pursued a policy of “urban renewal,” and enacted a series of laws granting municipalities the authority to designate certain historic areas as “renewal areas” slated for redevelopment. These policies are meant to enable municipalities and the Mass Housing Administration of Turkey (TOKI) to renovate unsafe areas and protect the city’s cultural and historic heritage. In practice, however, Turkey’s urban renewal policies have relaxed restrictions on construction in historic areas and opened the door for the transformation of historic residential areas into highways, airports, gated communities, shopping malls, luxury housing, and office buildings. Most importantly, TOKI typically displaces urban poor or squatter settlements in older parts of Istanbul which abut very expensive real estate in the expanding city (Turkun, 2011). For example, from 2007 to 2010, the Istanbul municipality forcibly evicted nearly 5,000 families in Sulukule, a historic Istanbul neighborhood inhabited by Romani people for hundreds of years, to make room for “Ottoman style” housing developments (Young, 2011).[1] Local activists, scholars, and residents in Turkey called into question the impact of these laws, arguing that they serve as a pretext for evictions to benefit the previously declining real estate and construction sectors. They have also taken issue with the way the government defines “risk areas” and the absence of any citizen participation in the projects (Balamir, 2013; Tarakçı & Özkan, 2015). In Istanbul, for example, the Networks of Dispossession project studies the relationships between public and private sector actors involved in urban mega-projects and produces information on the way Turkey’s “urban renewal” projects impact the surrounding communities. A group of volunteer activists, artists, journalists, lawyers, and urbanists began the Networks of Dispossession project in 2013. Using data and information from public records including corporations’ web pages, newspaper articles, and government databases (Gribat, 2015), NOD uses an interactive network mapping software—Graph Commons—to map networks of power and capital involved in large-scale urban development projects. They document government-seized properties in Istanbul, instances of displacement, labor-related deaths during demolition and construction processes, as well as environmental impacts of projects. Their publicly accessible network maps are an important tool for activists, urbanists, advocates, academics, journalists, residents, and anyone else interested in the transformation of urban life and urban landscapes.

Figure 4: Networks of Dispossession displaying their maps at the MAXXI Museum “Istanbul. Passion, Joy, Fury” Exhibition in 2015-2016. Source: NOD (2013).

NOD consists of three main map categories to document dispossession in Turkey:

- Projects of Dispossession unveils and analyzes important and often complicated or hidden aspects of mega-projects and partnerships between public institutions and corporations for the public. Projects include the Istanbul airport project and loss of urban space; shopping mall plans that displaced residents in the Istanbul neighborhoods Tarlabasi and Sulukule; and the Grand Pera Project (shopping mall) which was set to demolish the historic Emek Theater in Istanbul, among others.

- Partnerships of Dispossession uncovers how private and public actors share power on executive boards of companies responsible for developing the mega-projects.

- Dispossessed Minorities shows both urban contemporary dispossession and government confiscation of property previously owned by non-Muslim minorities in Turkey, such as the Armenian and Greek communities. The map shows which properties have been seized, the communities that used to own the properties, and the state institutions or private companies that have taken ownership. Turkey has a law that allows for minority communities to reclaim seized properties but this law does not take into account properties that may have been demolished or communities that may have migrated (Gribat, 2015). Nevertheless, the map allows communities to trace the seized property’s history and its reclamation over time.

Much like other MENA states, the Turkish state withheld data on urban projects from the public, thereby diminishing the power of local communities and grassroots efforts to analyze data and mobilize citizens on critical issues facing the future of their cities. In this sense, NOD serves as an “urban watchdog.” Throughout Turkey and especially in Istanbul, NOD provides activists, urbanists, academics and the public access to data and information about the urban mega-projects—an important tool for advocating greater transparency and participatory planning in the urban transformation process.

The case of megaprojects highlights the importance of calling attention to the unique experience of such projects within the MENA context. Whether a new urban communities project in Egypt, a luxury beachside resort in Lebanon, or an “urban renewal” project in one of Istanbul’s historic neighborhoods, megaprojects across the MENA carry unforeseen risks that more often than not, benefit those with access to power and capital, and disproportionately burden middle and lower-income communities. The megaproject and real estate-driven urban development model is a central tenet of the urban modernist planning and development paradigm so prevalent throughout the region. Barthel (2010) argues that certain patterns of urban development have emerged across the Arab world, particularly with respect to the shape and character of megaprojects, and that these patterns unite Arab cities in the way a neoliberal global urbanism has manifested itself there. First, Barthel argues, urban megaprojects are taking place in non-democratic states, and thus, the involvement of stakeholders differs from those in megaprojects in Western contexts. “Megaprojects exist in Arab countries because of the ‘throne’ (namely the King or President)” (Barthel 2010, 137). The participation of the ruler or ruling family in such projects results in their taking on a more informal character, in which the entire process depends on exemptions and exemptions to existing planning laws. Second, the involvement of Gulf investors and the emergence of a “trans-Arab capitalism” has resulted in a proliferation of large-scale projects in developing Arab countries, in locations with potential for speculation and fast return on investment. Third, megaprojects in the Arab world are marked by the absence of a participatory approach. Despite this, a new “blogosphere” criticizing major projects has appeared on the Internet, particularly in Tunisia. Finally, megaprojects serve as a substitute for urban strategies in the Arab world—a sort of distraction. Computer-generated images and 3D models serve to “screen, minimize, or hide unresolved issues in terms of metropolitan strategy, including organizational design and urban governance” (Barthel 2010, 139). Urban development projects are often the physical embodiment of the visions that dominant actors aim to promote about how cities should look, who should be included among its residents, and who should be entitled to participate in its making and management (Deboulet & Fawaz 2011). The similarities among urban megaprojects across the region represent just one of the many examples of how MENA urbanists could benefit from a common platform, upon which to share knowledge and best practices. There are certainly compelling differences among the experiences of MENA urbanists, too, and these differences represent an equally important opportunity for learning about the contours and variations of the urban experience across the MENA.

Conclusion:

By challenging existing urban planning patterns and offering alternative visions, MENA urbanists are contesting dominant visions of the city and carving out their own urban spaces. As such, MENA urbanists continually produce and present innovative methods to handle urban challenges and can work with their allies within government sectors as well. These organizations resist the privatization of already scarce public spaces; document the conditions of informal settlements in megacities; critique local governments’ poor urban management policies; introduce new tools to preserve architectural heritage in MENA cities; collaborate to present new methods the public sector can adapt to implement waste management and urban infrastructure upgrades; and countless other activities critical to realizing just, sustainable, safe, and inclusive cities. We believe that this regional mapping platform that TADAMUN is launching online will engender new networks of solidarity and coordination with local and regional MENA urbanist organizations and initiatives. We hope that this platform and our other activities will not only strengthen and support their work, but also help to create meaningful change in the way cities are planned, managed, and lived in. Our Mapping Urbanism platform can serve as a useful collaborative tool towards that end.

[1] The right to the city is “the right of all inhabitants, present, and future, to use, occupy, and produce just, inclusive, and sustainable cities, defined as a common good essential to a full and decent life” (Global Platform for the Right to the City, N.d., 2). It is a collective and diffuse right and entails conceiving of cities as commons, in which all inhabitants should have equal access to urban resources, services, goods, and opportunities of city life; and participate in the making of the city (Global Platform for the Right to the City, N.d.). The right to the city was first proposed by Henri Lefebvre in his 1968 book of the same title (Le Droit a la Ville). Lefebvre summarizes the concept as “a demand for a transformed and renewed access to urban life.” A number of popular movements have incorporated the idea of the right to the city into their missions and Brazil even wrote the right to the city into federal law with its 2001 City Statute. Most recently, the right to the city was incorporated into the New Urban Agenda—the outcome document agreed upon at the United Nations Habitat III conference in 2016.

[2] For more information on the Global Platform for the Right to the City, please see their website and this Tadamun article.

[3] Read about Sulukule’s history and the impact of renewal in the 2008 Sulukule UNESCO report.

Works Cited

Allegra, M., Bono, I., Rokem, J., Casaglia, A., Marzorati, R., & Yacobi, H. (2013). Rethinking Cities in Contentious Times: The Mobilization of Urban Dissent in the ‘Arab Spring.’ Urban Studies, 50 (9), 1675-1688. DOI: 10.1177/0042098013482841.

Bagaeen, S. (2016). Reframing the Notion of Sustainable Urban Development in the Middle East. Open House International, 41 (4).

Balamir, M. (2013). Obstacles in the adoption of international DRR policies: The case of Turkey. Background paper prepared for the global assessment report on disaster risk reduction, 2-24.

Barthel, P. (2010). Arab Mega-Projects: Between the Dubai Effect, Global Crisis, Social Mobilization, and a Sustainable Shift. Built Environment, 36 (2), 132 – 145. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23290061.

Civil Campaign for the Protection of al-Daliyah of Raouche (CCPDR). (2014). Dalieh Research Booklet. Retrieved from http://dalieh.org/assets/booklet-en.pdf

Davis, D., & de Duren, N. L. (2011). Introduction: Identity Conflicts in the Urban Realm. In Davis, D., & de Duren, N. L., Eds. (2011). Cities and Sovereignty: Identity Politics in Urban Spaces (1-14). Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press.

Deboulet, A. & Fawaz, M. (2011). Contesting the Legitimacy of Urban Restructuring and Highways in Beirut’s Irregular Settlements. In Davis, D., & de Duren, N. L., Eds. (2011). Cities and Sovereighty: Identity Politics in Urban Spaces (116-151). Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press.

Dictaphone Group. (2013.). This Sea Is Mine Research Booklet. Retrieved from Dictaphone Group website: from http://www.dictaphonegroup.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/SIM-booklet-compressed.pdf

Flyvbjerg, B., Bruzelius, N., & Rothengatter, W. (2003). Megaprojects and Risk: An Anatomy of Ambition. Cambridge University Press.

Global Platform for the Right to the City. (N.d). What is the Right to the City?” Accessed: http://www.righttothecityplatform.org.br/download/publicacoes/what-R2C_digital-1.pdf

Gribat, N. (2015). Interview with Yasar Adanali, Founder of Networks of Dispossession project. Sub/Urban Magazine, 3, 153-164.

Networks of Dispossession (NOD). (2013). Networks of Dispossession Information. Retrieved from https://burak-arikan.com/networks-of-dispossession/

Saksouk-Sasso, A. (2015). Making Spaces for Communal Sovereignty: The Story of Beirut’s Dalieh. Arab Studies Journal, 23(1), 296.

Sheppard, E., Gidwani, V., Goldman, M., Leitner, H., Roy, A., & Maringanti, A. (2015). Introduction: Urban Revolutions in the Age of Global Urbanism. Urban Studies, 52 (11), 1947-1961.

Tarakçı, S., & Özkan, A. (2015). Evaluation of Law no. 6306 on Transformation of Areas under Disaster Risk from Perspective of Public Spaces – Gezi Park Case. Iconarp International Journal of Architecture and Planning, 3(1), 63-82.

Türkün, A. (2011). Urban regeneration and hegemonic power relationships. International planning studies, 16(1), 61-72.

Vale, L. (2011). The Temptations of Nationalism in Modern Capital Cities. In In Davis, D., & de Duren, N. L., Eds. (2011). Cities and Sovereighty: Identity Politics in Urban Spaces (196- 208). Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press.

Walton, V. (2009). Seeing from the South: Refocusing Urban Planning on the Globe’s Central Urban Issues. Urban Studies, 46(11), 2259-2275. DOI: 10.1177/0042098009342598.

Comments