The Mustafa Al-Nahhas Corridor Development Project: A Lost Opportunity?

In rapidly urbanizing Cairo, Cairenes face a daily transportation challenge. Road congestion adds a burden on the economy and the environment, as people spend hours in traffic jams commuting to work and moving across the city. Only a small percentage of the population owns a private car (approximately 14% in Cairo), with millions largely depending on public transportation.

A large and densely populated city like Cairo and its surrounding area needs a full complement of public transportation options which typically include metro, light rail, and bus systems. Creating the right balance among these options can greatly improve the overall effectiveness of a public transportation system and reduce traffic congestion. Cairo has invested billions of dollars in a metro system since 1987 and continues to do so, opening the third metro line in 2014 with plans for several more over the coming years. Government operated buses as well as private microbuses are common throughout the city, servicing areas that the metro does not reach. To complement this system, the government has plans for supertrams or high-speed trams that connect the city core with some of the newer satellite cities. Some announcements have been made about these ambitious supertram projects but they remain unrealized dreams due to their high cost and the difficulty in financing the project.

One option the government has not explored is a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT). A BRT is a high-capacity surface-level bus system that mimics the speed and efficiency of a metro (or supertram) with capital costs 4–20 times lower than light rail systems (or supertram) and 10–100 times lower than metro systems. BRTs achieve this speed and capacity by using bi- or tri-articulated buses that can hold up to 200 passengers that ride on dedicated bus lanes on major transportation corridors, bypassing all other traffic. The system depends upon set standards in order to achieve speed, predictability, and convenience at relatively low cost.

The first BRT system was established in 1982 in Curitiba, Brazil, by the Institute of Urban Research and Planning of Curitiba (IPPUC) and has since spread to more than 150 cities throughout the world including places as diverse as Delhi, India; Istanbul, Turkey; and New York, USA. Unfortunately, the Egyptian government has not taken the idea seriously enough, even though international institutions have promoted them.

In 2014, UN Habitat issued a request for proposals for BRT corridors in Cairo in order to encourage an eventual BRT project in Egypt. The World Bank also explored the potential for a BRT system in Cairo in a 2014 study suggesting that investing in the BRT system made more sense than building more roads which would only increase car traffic.

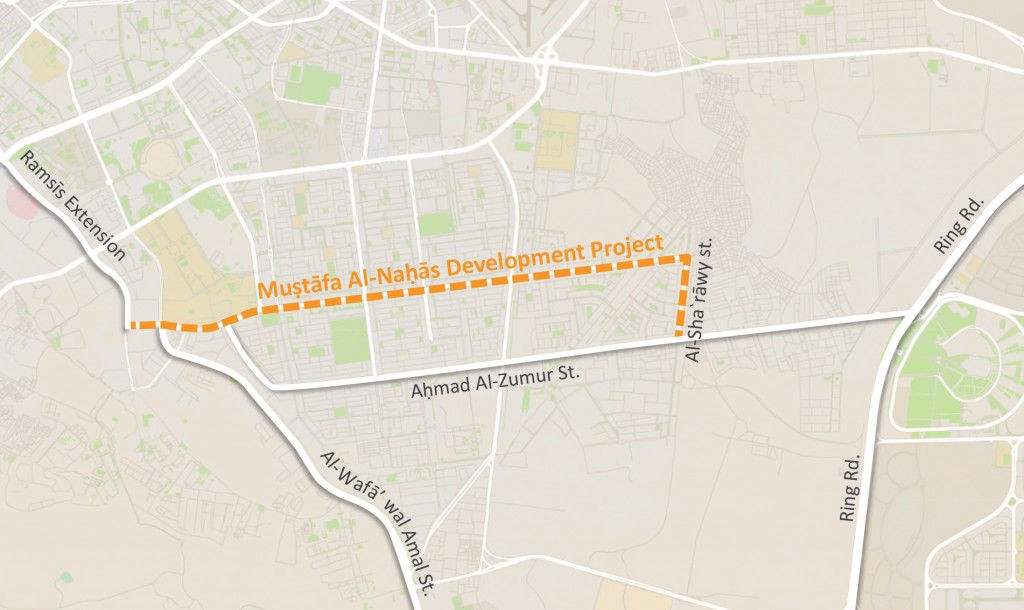

Cairo’s government realizes it also needs to find solutions to the notorious traffic jams, lengthy commute times, and air pollution caused largely by the growing numbers of private cars, but limited financial resources prevent it from completing more ambitious infrastructure projects. In light of these issues, the Development Authority in Greater Cairo, affiliated to the Ministry of Housing, Utilities, and Urban Communities and the Cairo Governorate launched a new transportation project in 2014 focusing on Mustafa Al-Nahhas Street in Nasr City meant to relieve traffic congestion in the area. The project established a dedicated bus lane in the center of the street beginning at the intersection with Ramsis street and running 8km to the intersection with Metwally al-Sha’rawi, covering the old tram tracks which had stopped working around seven years ago, and widening the existing street slightly. This project was meant to be part of an integrated development of roads and transportation corridors at the greater Cairo level, in order to reduce traffic congestion in the capital. Other nearby road rehabilitation projects on Al-Shaheed, Emtedad Ramsis, Al-Petrol, Al-Sharekat, Al-Khalifa Al-Zaher streets, and Al-Sha’rawi Street will complement the Mustafa Al-Nahhas bus corridor.

Mostafal Al-Nahhas development project and its surrounding area

Credit: TADAMUN. image source: Google Maps

Despite the government’s high hopes for the Mustafa Al-Nahhas bus corridor, the 60 million EGP development project was highly criticized by residents after it was completed and did little to reduce congestion—in fact, in some areas, it may have made the situation worse. On social media, headings about the project included: “Death under government supervision,” “the highway to death” and “stop the Mostafa Al-Nahhas disaster.” In principal, the idea of a dedicated bus lanes was a good one, but as the government has now learned, a dedicated bus lane alone does not necessarily create a good bus experience.

Mostafa Al-Nahhas street. Photo source : @Muhamed3amr

Unregulated traffic flow at intersection on al-Sha`rawi st. (Photo: Heba Mannoun, used with permission)

Residents can take comfort in the fact that this bus corridor is only temporary, serving as a stop-gap measure for a more ambitious “supertram” project which would resuscitate the tram lines that are now buried under asphalt to build a modern, 44km tram line capable of reaching 35 km/hr connecting New Cairo to the existing metro system. In 2010, the Minister of Transportation, Alaa Fahmy, announced the completion of a feasibility study for the five billion EGP, 48-month project, which was to be supported in part by the World Bank. For many reasons, the supertram has not seen the light of day, nor will it anytime in the near future.

So for now, Mustafa Al-Nahhas has a dedicated bus lane and the government should seize the opportunity to experiment. With a modest investment and strategic improvements which we discuss below, the lane can be modified into Cairo’s first BRT corridor and provide a model that can be replicated throughout the city, perhaps allowing the government to forget all about that supertram and its five billion pound price tag.1

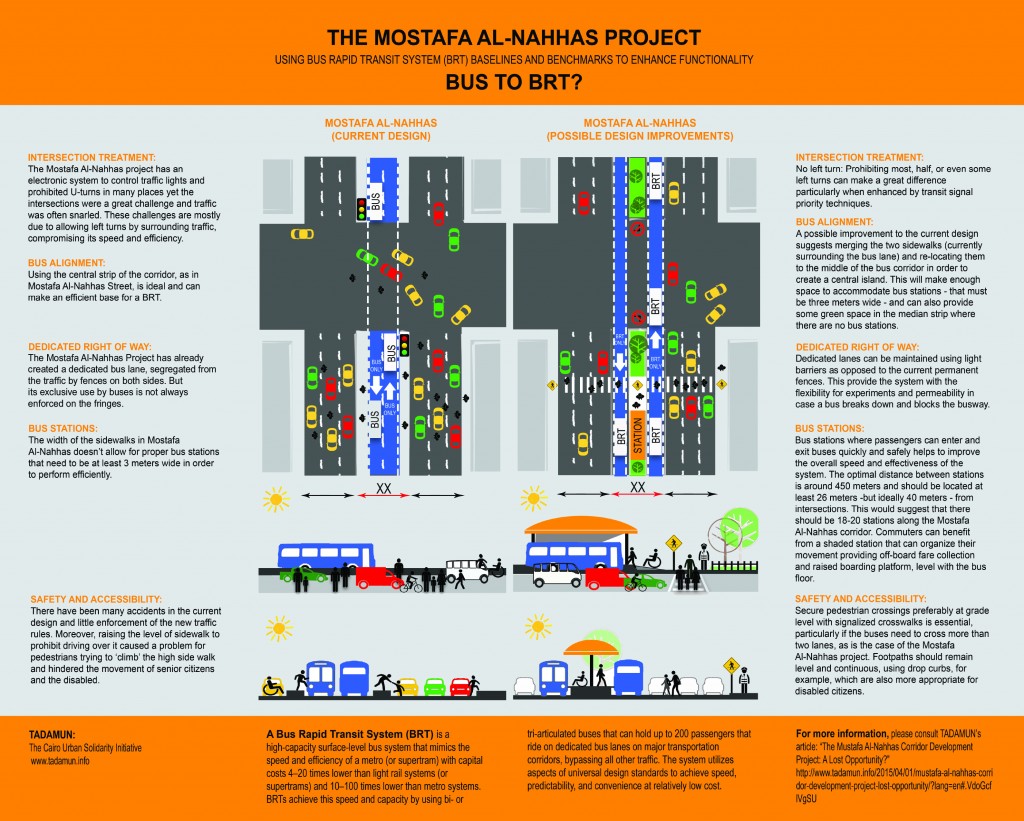

Dedicated Right of Way

The most fundamental component of a BRT system is a dedicated right-of-way, much in the same manner that a metro system has dedicated tracks. Mustafa Al-Nahhas already has a dedicated bus lane, but its exclusive use by buses in some areas is not enforced. The buses in the eastern extension of the Nahhas Corridor (al-Sha’rawi street) often share their dedicated lane with cars, microbuses and even tuktuks (rickshaws). The main goal of providing separated bus lanes and enforcing right of way is to make sure that cars do not block bus routes and slow down the buses, thereby ensuring the fastest possible speeds for buses to move along the corridor.

Creating a dedicated right-of-way requires barriers. The Mustafa Al-Nahhas corridor started with a sidewalk acting as the only physical barrier separating the bus lane from other lanes. A Fence was later erected separating vehicular traffic, and regulating pedestrian crossings through specific openings near bus stops. Creating a true separation of the bus lanes from the other lanes can be achieved by permanent, semi-permanent, or temporary physical barriers. Temporary barriers can offer project designers flexibility and a period for experimentation to see what works best to improve traffic problems. It is not easy to estimate how change in one corridor will affect the larger transportation network, so having some flexibility is a virtue. However, permanent barriers generally do a better job of keeping cars and people out of the bus lane. No matter what choice is made, this ‘hardware’ needs to be accompanied by a softer yet powerful component: law enforcement. Unfortunately, if cars do not obey traffic rules and enforcement is very weak, the design will not work.

Bus alignment

Another core aspect of a functional BRT is bus alignment—: the allocation of a section of the road for the exclusive use of the BRT. Using the central strip of the corridor, as in Mustafal Al-Nahhas Street, is ideal and can make an efficient base for a BRT. In other designs, when bus lanes are on the right side of the street, the buses may be forced to move more slowly when cars need to turn right or delivery trucks need to service street-side commercial enterprises.

Bus station Design

Well-designed bus stations where passengers can get on and off the buses quickly and safely is another component of a BRT that helps to improve the overall speed and effectiveness of the system. This is one major shortcoming of the Mustafa Al-Nahhas project—there are no stations whatsoever.

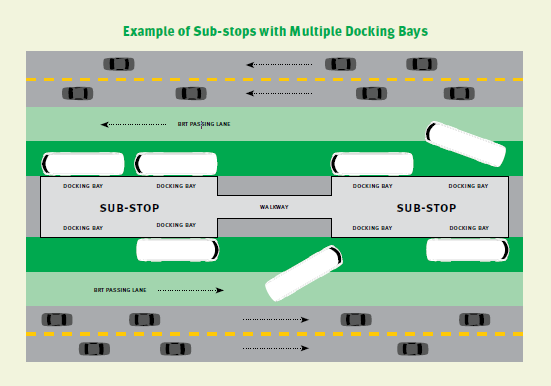

According to the BRT Standard, developed by the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy, the optimal distance between stations is around 450 meters. More distant stations would demand that people walk farther for the bus (and perhaps reduce bus usage) and a smaller number would reduce the system’s speed. Research has also demonstrated that bus stations should be at least 26 meters, but ideally 40 meters, from intersections to avoid delays and slower traffic as buses wait for cars to make turns. This would suggest that there should be 18-20 stations along the Mustafa Al-Nahhas corridor including the origin and terminus stops. Ideally, the origin and terminus stops should connect to other transport modes (rail, pedestrian, metro, etc.).

Well-designed bus stations can improve the system substantially by providing a safe and comfortable environment for passengers. Even within a station that is only three meters wide (the minimum for a BRT), commuters can benefit from a weather proof station that highly enhances the users’ experience. Within the available space on Mustafa Al-Nahhas Street, the government could build open-air stations with strong shading elements for the sun.

A center platform station in Quito, Ecuador

Photo Source: The BRT Standard

Example of multiple Bus stops

Photo Source: The BRT Standard

Two important design elements of station design are off-board fare collection and platform–level boarding which can greatly improve the efficiency of the BRT system.

Off-board fare collection

One of the factors that slows buses down is the time it takes for passengers to get on and off the bus. When passengers have to pay on the bus, this results in lengthy lines. Off-board fare collection eliminates the possibility of lengthy lines while passengers board the bus and reduces the time buses must wait at each stop.

There are two standard ways cities have dealt with off-board fare collection. The station can be designed as a gated waiting area where passengers must first pay to enter, similar to the way metro riders must pay to access the boarding area, or stations can include automated ticket machines where riders can buy their tickets before boarding and an inspector can check the tickets on board. The buses in Cairo already work relatively efficiently in this regard, as passengers will first board, then pay the fare to the ticket collector in the back of the bus.

Raised boarding platform to be level with the bus floor

A boarding platform raised off of the ground to be level with the bus floor minimizes delays when boarding or exiting the bus. It also enhances safety, particularly for the elderly, children, the disabled, and makes boarding for people with luggage easier, by reducing any gap between the station and bus floors and eliminates the need to climb steps board the bus altogether.

Attractive Design

The best BRT systems not only enhance the user experience and increase the public transportation system’s efficiency and speed of travel, but also include aesthetically interesting and well-designed buses and stations that project a positive image of the city. A business model of public-private partnerships can be useful when introducing, financing, and designing a new BRT system and high-end designs within a city may attract more investment to the areas serviced by the BRT. Yet, attractive design does not necessarily mean high cost; on the contrary it could mean culturally relevant and environmentally-friendly design. Stations can also provide passengers with real-time travel information, letting them know when the next bus will arrive, through real time electronic panels or up-to-date information tables to increase customer satisfaction and enhance the overall BRT experience.

Bus rapid transit stations in Curitiba, Brazil

Photo Source: Global Site plans

Curitiba, Brazil, set the gold-standard in station design when they introduced cylindrical, transparent “tube bus stops” with turnstiles, steps, and wheelchair lifts in the 1980s. Passengers paid their fares as they entered the stations and waited for buses on raised platforms. Instead of steps, buses had extra wide doors and ramps that extended out to the station platform when the doors opened. This off-board fare collection plus the same-level bus boarding resulted in a typical dwell time (the amount of time a bus waits a station for riders to get on and off) of no more than 15 to 19 seconds per stop. Eventually, these tube stations became the trademark of the Curitiba bus system and cities across the globe imitated them for their own BRT systems.

Dealing with Road Intersections

The main goal of intersection treatment is to increase the uninterrupted flow of buses (sometimes called a ‘green wave’) and it is one of the basic elements of a ‘proper’ BRT system. The two most common strategies employed are to prohibit turns across the bus lane and to organize traffic lights to the advantage of buses rather than cars. Making the decision about prohibiting all turns across the bus way might be difficult and could increase congestion in other places however prohibiting most, half, or even some turns can make a difference particularly when enhanced by transit signal priority techniques. The Mostafa Al-Nahhas project has an electronic system to control traffic lights and prohibited U-turns in many places. However, the high traffic flow in streets intersecting al-Nahhas and the limited number of intersections and U-turns result in traffic bottlenecks throughout the corridor. For a BRT system to operate effeciently, the selected street should ideally be the major traffic artery, which is not the case in al-Nahhas, as many of the intersecting streets (Abbas al-’Aqqad st., Makram Ebeed st., and a few others) are equally important traffic routes with heavy vehicular flow. For the Nahhas corridor to be successful the vehicular flow of these intersecting streets need to be separated – potentially through overpasses or tunnels.

Safe Access

Safe pedestrian access to bus stations are also a priority. BRT systems utilize secure pedestrian crossings preferably at ground level with signalized crosswalks, particularly if the buses need to cross more than two lanes, as is the case of the Mustafa Al-Nahhas project.

Pedestrian crossings placement along al-Nahhas is an unsafe feature, forcing diagonal pedestrian crossing.

Well-lit crosswalks where the footpath remains level and continuous, using dropped kerbs, for example, are also essential. Universal design features, that enable disabled citizens to use public transportation independently, requires incorporating braille readers and tactile ground surface indicators, among other features, into the BRT system. As mentioned earlier, the fences along the Nahhas corridor limits pedestrian crossings to specific routes, however the location of the entry points through the fences aren’t parallel to each other (see photo below), causing pedestrians to cross the bus lanes diagonally. According to the public feedback about the Mostafa Al-Nahhas project, safety and accessibility were a great challenge to passengers and pedestrians and there were many accidents and little enforcement of the new traffic rules.

Universal access: Eugene, Oregon, USA

Photo source: The BRT Standard

Service Integration

Beyond the technical parts of an efficient bus system, using standard BRT baselines and benchmarks, overall service integration and interconnectivity with other public transport networks to guarantee service consistency is also critical. Locating transportation nodes close to each other and unifying the fare system across different parts of a transportation system will improve its integration. The system’s efficiency can also be enhanced by offering limited services that skip low-demand stations or express services that carry passengers from one end of the corridor to the other end without stopping. Finally, if multiple routes operate on a single corridor or over multiple corridors, it will lower capital investments and collectively increase the system efficiency.

Conclusion

Mustafa Al-Nahhas is one of the important corridors that connect Nasr City with the city center through Ramsis street extension and the 6th of October Bridge, as well as with Eastern satellite cities through the Ring Road. It is surrounded by many corridors that are being developed simultaneously within the integrated transportation project for that area, which make it a good candidate for such capital investment.

To conclude, in a vast metropolitan area such as the Greater Cairo Region, high capacity public transportation systems are certainly needed and should be the benchmark for any new transportation project. Yet, given the limited resources it is worthwhile to experiment with universally proven solutions especially when they cost less than other public transportation systems such as metros. In the Mustafa Al-Nahhas case, the government has already made some infrastructural improvements for a bus system, but in the long term they hope to build more ambitious and costly supertrams. Given the overll characteristics of a BRT as well as its low cost, it would have been more efficient to have developed Mustafa Al-Nahhas into a BRT rather than wait for capital investments for a supertram.

While debates about the advantages and disadvantages and costs of high capacity transport options—metro, light rails, super trams, or high capacity bus systems—are ongoing, the ideal solution is to utilize all the available options to find a balance between cost, speed, and coverage. An integrated system has more potential to serve different groups and solve specific transport problems. A BRT can be a cost-effective option particularly on the city outskirts where space is more available for dedicated bus lanes to serve Cairo’s exurbs and can intersect with the new extension of two metro lines that will eventually link 6th October city to the Cairo airport. Connecting these modes with walkability or even bikeability can reduce urban pollution. In a city like Cairo, doing nothing is not an option, but the worst case scenario would be to initiate a project that wastes public resources with no significant positive effect on people’s lives. Incorporating standard BRT components into the Mustafa Al-Nahhas bus corridor would probably demand more investment, but it would be an investment that would pay off even in the medium term, and certainly in the long term. Yet, fantasizing about expensive projects like the supertram in the current economic climate, suggests an indifference towards a citizen’s basic right to safe, accessible, and affordable public transportation. The Mustafa Al-Nahhas corridor still has great potential for a cost-effective high-capacity public transportation project, yet the opportunity will be lost, unless there are innovative, creative, cost-effective, and pragmatic design improvements made very soon.

Comments