[Re]imagining Urban Housing Demand

Given the popular media’s approach to the subject of housing demand, it is not surprising that housing demand is treated in an essentialist manner. Recurrently announced government housing projects such as the first and second Million Housing Units projects – which usually do not achieve their promises – imply that Egypt’s housing crisis is an expression of a mere numerical imbalance, that can be resolved by increasing the supply of new housing units. However, housing demand’s complexity surpasses simple numerical calculations.If we do visualize demand only as a number, a series of distorted images will flash before our eyes. First, we will assume that Egypt’s growing population inherently pushes housing demand to increase. This assumption may not always play out in reality because not every newly formed household carries the purchasing power parity to demand new housing. A simplistic conception of housing demand also assumes that one can simply pick up a population living in high density areas, and relocate it in low-density expanses. Again, this ignores the preferences of demanders, which constitute pivotal factors that determine overall housing demand. Numerical conceptions of housing demand can thus de-humanize the subject-matter, and disengage it from the socioeconomic context in which it is supposed to be positioned.

To understand housing demand in Egypt, we must first position it within a socio-economic context, list its various types, understand how other researchers have measured housing demand, and then focus on providing a comprehensive picture of housing demand and need in Egypt in particular. Based on this, the paper proceeds in the following order: First, it explains the concept of demand in economics. Second, it reiterates an academic understanding of the limits of a purely economic conceptualization of housing demand. Then, it lists the conditions and determinants of housing demand, summarizes the different types of housing demand, and Introduces some methods for measuring housing demand. Finally, it provides a snapshot of Egypt’s demand through qualitative and quantitative perspectives, based on available secondary sources. The aim of all sections combined is to provide a more comprehensive approach to our understanding of Egypt’s urban housing demand.

Understanding the Concept of Demand: Defining terms

Housing demand is commonly defined as the total number of houses demanded by a population in a specific period. However, this definition lacks depth because it does not indicate the scope of what the number actually expresses. Housing Demand must concerns not only the wish or need to own a house, but also the capacity to pay the price. It is equally important to note that housing demand is not only a numerical value, but also a prediction of preferences (Boumeester, 2011). In Egypt, if we were to measure demand, we would have to study the variety of choices people make when moving to new housing units such as where they prefer to live, for how long, and what kind of house they prefer to own/rent. By implication, a well-rounded definition of housing demand is this: it is the measurement of preferences and numerical predictions of housing choices at a specific time, given the economic constraints and opportunities of the market economy.

Because housing demand stems from economics, it is subject to the laws of demand and supply and the relationship between them.1 The relationship between supply and demand shows the cyclical nature of the market economy; 1) first, when demand increases, prices increase; 2) then, this surge in prices initially increases quantity supplied, but then eventually the hiking of prices decreases quantity demanded; 3) when demand decreases, supply decreases again, pushing prices to drop; 4) when the prices drop, demand increases and the cycle unfolds again.

As is commonly the case in market economics, equilibrium between demand and supply is rarely reached, either due to excess supply or excess demand.2 In the housing market, there could be an over-supply of a certain type of housing (e.g. high-income housing), and concurrently an under-supply of another (e.g. low-income housing).

Demand is directly related to prices, but other factors are also important to acknowledge in the research process. Let us first imagine that the relationship between demand and prices is an inverse curve on a graph. A movement along the curve occurs when there is a change in the prices of goods. Yet, the whole curve shifts either upwards or downwards, when the quantity demanded is affected by a factor other than price (Heakal, n.d.). To elaborate, let us hypothetically assume that Egyptians mainly demand three different apartment sizes every year: 50% of Egyptians demand 70m2 apartments, 40% demand 90m2 apartments, and 10% demand 120m2 apartments (hypothetically). Every year, suppliers place these three apartment sizes on sale. However, let us assume that in year X, suppliers only placed 90m2 apartments for sale for whatever reason. In that case, there will be a shift in demand channeled towards 90m2 apartments, because they now constitute the only apartment size available. The reason there is a shift not a movement is because the increase in the demand for 90m2 apartments was not the consequence of fluctuations in the prices of apartment units, but rather a reaction to the type of apartment units supplied in the market.

Although it is important to keep in mind the economic nature of housing demand, Danny Dorling, a professor of geography in Oxford University, warns against exclusively studying previously mentioned economic indicators (changes in prices, equilibrium/disequilibrium, and shifts/movements along the curve) to understand, calculate and predict housing demand. He argues that housing is not only a traded asset, but also a social good that represents human need (Shook, 2014). According to him, numerical calculations can be too theoretical, and not on par with people’s actual experiences, and the problems they might face as they engage with the housing market. Dorling focuses on England’s housing economy, which many in the UK believe is in a healthy condition, as is indicated by the hiking up of the prices of housing units. However, interestingly Dorling finds that despite the rising housing prices, England is suffering from a housing crisis. With less people able to afford purchasing housing units, the majority of people in England are now renting. Because landlords are demanding unreasonable renting prices, a large number of families find themselves having to frequently disrupt their lives in order to move, as they attempt to search for more affordable units. Economic indicators don’t show the sense of constant instability, undesired movement, homelessness, and class cleansing people face. Numerical increase in demand is therefore misleading because in reality it only projects a certain kind of demand, namely that of high-income groups such as landlords. Mid- and low-income households are not on the winning side of the housing boom. Their level of demand is decreasing and its type is changing from one channeled towards purchase to one focused on rents.

This revelation makes us realize that within the macroeconomic picture of demand, there may be other cycles going on which are not accounted for on a larger scale. Therefore, it is not enough to estimate total housing demand, or to simply study fluctuating prices in order to realistically grasp the housing situation in any given country. Rather, it is pertinent to break down these terms and indicators, and to search for different types of demand and possible smaller-scale cycles unfolding within the larger macroeconomic framework.

When demanders approach the housing market, they stand at very different starting points from a financial vantage point. The richest have enough capital to purchase several housing units, the middle-income earners have only sufficient capital to rent, while the poorest do not have sufficient capital to do either. A very similar situation is present in Egypt, where high-income earners own several units in a variety of locations, while low-income earners are typically unable to afford a single unit in the formal housing sector. Accordingly, we must expand the economic context of housing demand to relate it to the condition of the national economy as a whole.

Conditions and Determinants of Housing Demand

Having established that housing demand must be placed within a socioeconomic framework, the question then is: what are the determinants of housing demand? In other words, what factors affect housing demand? Ultimately the measurement of housing demand depends on the housing preferences of households on the one hand, and the types of housing units available on the other. A household here refers to a demographic unit composed of a certain number of persons that shares a single housing unit. The unit may take the form of a single family, several families living together, a single person, single persons living together, single persons and families living together, etc. Factors that affect demand must carry an influence on either one of these two elements: households or housing units.

Demographic changes are the most obvious factors affecting housing demand. Social demography refers to the domestic and international migration patterns of inhabitants (Ableti, Marco, & Gebremedhin, 2011). Changes in the distribution of people affect both the number of desired housing units and the different types of housing units demanded (Thompson, 2014). For example, an economically prosperous location in a city typically increases housing demand for that particular area, and influences the size and structure of desired dwellings, depending on density levels. Migration and movement thus determine housing demand across various regions.

Natural demography is likewise a major determinant of housing demand. Population growth may push quantity demanded for new housing units to increase. However, that is not always the case, because not every newly formed household will have the capacity to purchase new housing units. In fact, many households tend to absorb excess demand through overcrowding. To escape numerical reductionism, it becomes crucial to further qualify the population by measuring other demographic changes such as family size, marital status and changes in age group percentiles.

In that light, households can be young or old, big or small, formed of one person, a couple, a nuclear family or several families living in the same housing unit, etc. Depending on these demographic characteristics of households, housing demand is shaped both quantitatively and qualitatively.

Income levels also affect housing demand in multiple ways. A rise in income levels may give birth to the emergence of new manifestations of demand, thus increasing demand both numerically as new household may emerge and want new units, and qualitatively as current households will probably want to live in larger housing units, or to reside in particular locations.

Other factors, such as affordability and expected changes in prices of units , affect housing units, thus impacting housing demand. With regards to affordability, the general rule is: the more affordable a housing unit is, the higher the quantity demanded for it. Affordability can be affected by 1) a change in the prices of housing units due to either economic growth or recession; 2) a change in current taxation and subsidy policies for houses, which may dissuade/induce consumers to purchase new dwellings. Expected changes in the prices of units also affect consumer’s choices regarding housing. When prices of units are expected to carry more value in the future, speculative demand ordinarily increases among high-income earners, while low-income earners become marginalized – which is the case in the Egyptian real estate market. Actual and expected changes in price are therefore important determinants of housing demand.

The availability and location of housing units are also important determinants of housing demand. For example, in the Philippines, researchers found that the shortage in the supply of rental units negatively affected housing demand, because people wanted a particular type of tenure which was not available (Ballesteros, 2002).The location of the housing units offered for sale also affects housing demand in a similar fashion. Houses offered for sale in distant locations, are likely to have a negative impact on the quantity demanded by consumers who opt for houses in areas close to amenities and social networks. Affordability, government policies, availability and location all impact overall housing demand, either driving it to surge, or pressuring it to decrease.

Types of Demand

As was previously revealed by Dorling’s research, typifying demand makes assessment for housing less ambiguous and more useful for policymakers. A common way to qualify demand is in terms of quantitative and qualitative standards . Quantitative standards refer to the number of rooms in a dwelling, or a minimum amount of housing space per person. This type of demand can be used to measure space-to-persons ratios, in order to assess levels of overcrowding and vacancy. Conversely, qualitative standards refer to the presence of specific elements considered pivotal to urban life, such as running water, indoor toilets, electricity, ventilation, accessibility of sunlight, the type of material used for construction, the age of dwelling units. They also include access to public transportation and services, and proximity to places of employment. In short, qualitative standards refer to “elements involved in the structural features of dwellings that distinguish a home from a mere shelter” (Ableti, Marco, & Gebremedhin, 2011).

However, people seem to prioritize between different qualitative factors in different ways according to their needs and abilities. For example, the presumption is that dwelling units that are too old or too hazardous to be inhabited are not fit for living. In Egypt, people may in many cases choose to live in such buildings due to other economic or social factors. There are countless cases of unsafe buildings collapsing, causing casualties and losses. The project ‘Egypt Building Collapses’, where researchers collected data on residential building collapses over the period from July 2012 until June 2013, reveals shocking facts: in one year, 392 collapses occurred all over Egypt, causing the death of 192 people and the injury of 379 others, and leaving 824 families homeless. The most frequent reason was collapses due to dilapidated buildings, which happened in 112 of the cases.

Dividing demand into qualitative and quantitative can thus help researchers qualify and properly assess the presence of a need for housing. More importantly, studying all the decisions people have made to choose their houses and how they prioritize between the different factors can shape a deeper perception of demand.

Demand for housing can also be categorized into effective versus latent demand. Effective demand refers to the amount of goods and services that consumers are currently buying in a given market. Latent demand, on the other hand, refers to demand that is non-existent at the moment, but may arise in the future due to changes in the economy, or a change in the financial abilities and preferences of consumers. In other words, latent demand is a “buyer or need that would be willing to purchase a particular product or service, but he cannot do so because he lacks the necessary funds or does not know of the product/ service” (Kimmons, n.d.) Together, effective and latent demand both produce “notional demand” (general demand) (Kimmons, n.d.) Dividing housing demand into latent versus effective demand is a useful tool for distinguishing between existing demand and possible, future demand.

Demand for housing can alternatively be classified into elastic versus inelastic. Elastic demand is the desire for a good that easily fluctuates in accordance to changes in prices. To clarify, goods whose quantity demanded significantly decreases when their prices increase are said to be highly elastic. Examples of elastic goods include cars and electronic devices. Meanwhile, demand for inelastic goods such as bread is not easily affected by price fluctuations. Dividing demand into elastic versus inelastic is useful for showing which type of household has the most fluctuating demand (young or old for example), and which type of dwelling is most easily affected by changes in demand spurred by economic fluctuations.

Another way to categorize demand is in accordance with the type of market sectors that consumers engage with. A “two-sector estimate of demand” divides the market economy into the private sector and the public sector. Housing demand for units supplied by the private sector is different – both quantitatively and qualitatively – from demand for units supplied by the public sector. Private sector housing is usually qualitatively more superior to the public sector, and customarily targets high-income households. In many developing countries such as Egypt, there is also demand for housing units supplied by a third sector of the market which could take the form of an intermediate supplier, the informal sector (Holmans, 2013). Typifying housing demand according to demand for private, public and informal sectors provides a comparative edge to the study of housing demand, revealing which of these sectors is most dynamic and why.

Methods for Measuring Housing Demand

There are mainly two methods for measuring housing demand. The first is called “housing need and demand study” and is a more comprehensive approach that deduces demand based on an all-inclusive assessment of the housing market, including the state of the economy, existing housing stock, expected demographic changes, and expected supply. The second – which is less comprehensive – aims to determine certain aspects of demand such as a comparison of demand in various locations, an analysis of particular types of household demand, etc. Both methods can depend on either primary research such as conducting surveys, or secondary research such as analyzing census data. They can also depend on quantitative research or qualitative data collection. Each of these methods, in its own right, provides a useful tool for understanding and measuring housing demand.

The housing need and demand study aims to assess housing need for particular groups, and to analyze “the extent of the need for affordable housing in a community” (BC Housing, 2010). It is usually based on 1) assessment of previously unmet demand; 2) prediction of newly arising demand; and 3) analysis of current supply (BC Housing, 2010). The purpose is to guide urban policy and to inform construction industries and financial institutions engaged in the housing sector. Below are the detailed stages of the housing need and demand study conducted by the Central Statistical Authority in Ethiopia and the Institute for Population Research-National Research Council in Italy, as we think each case can offer lessons for measuring demand in Egypt.

Case-study: “Housing Conditions and Demand for Housing in Urban Ethiopia”

Scope of the study: In this housing need and demand study, analysis was made for all of Ethiopia’s urban housing demand at the regional and national levels and for 13 specific towns (Ableti, Marco, & Gebremedhin, 2011).

Stage 1 – Assessing previously unmet demand: this includes first studying existing housing stock from both a qualitative and a quantitative vantage point; analyzing Ethiopia’s urban population; then classifying demand into demand for renovation versus demand for new housing units.

Stage 1A: The first step was assessing previously unmet demand (Part A). In order to assess previously unmet demand (or current need), researchers first studied existing housing stock from both a qualitative and a quantitative vantage point. Among other things, researchers calculated number of persons per room and number of rooms available in each unit. They also assessed type of building; construction material of walls, floor and roof; age of housing units (to assess both the condition of the units and the expected need for replacement); and housing units by type of lighting.

Stage1B: In this step, researchers analyzed Ethiopia’s urban population. They looked into the age, marital status, family life cycles (marriage, child bearing, departure of children from parental household, marriage dissolution, etc.) and percentage distribution of number of persons per urban housing unit.

Stage 1C: researchers used the information they gathered on the demography and the housing stock of the region to categorize unmet housing demand into: demand for renovation of already existing stock, and demand for the construction of new dwelling units.

Demand for renovation: This type of demand emerges due to the presence of qualitatively under-standard houses. Qualitatively under-standard houses are assessed according to the quality of construction materials, as well as the supply of essential facilities such as running water, indoor toilet, bathing facilities, and electricity. Also, traditional construction materials are assumed inadequate housing standard in this study. Thus, if a housing unit is of old age, and is depleted, it may need to be replaced with a new one. However, in some cases, when the qualities of houses are inadequate, they can be fixed using simple renovation intervention. Whether qualitative under-standards should be resolved through renovation or construction depends on the magnitude of the level of intervention needed; a house with a crack in the wall would only need renovation, while a house with several cracks in the walls caused by consistent water leakage would probably need to be demolished and replaced with a new one.

Demand for the construction of new dwelling units: This type emerges due to overcrowding. The study used the indicator of “Crowding Matrix” which relies on the ratio of number of persons to number of rooms. There are standard ratios to evaluate the level of acceptability of housing density among three categories: under-occupied adequately occupied and overcrowded. If the result exceeded a certain standard ratio 3, it is calculated as overcrowding that would be later translated into unmet housing demand. This type of unmet demand cannot be satisfied except through an increase in the dwelling units available.

Stage 2 – Assessing future demand: After measuring previously unmet housing demand, researchers then proceeded to assess future housing demand. This study does not take the additional step of comparing housing demand with current housing supply. According to the study, to assess future housing demand, we must account for population dynamics which result from social and natural fluctuations (Ableti, Marco, & Gebremedhin, 2011). The combination of future housing demand and previously unmet demand provides us with an estimate for overall urban housing demand.

Measuring Egypt‘s Housing Demand

As noted before, the flawed perception that demand can only be stated as pure numbers led the country to series of unsuccessful solutions for its housing crises, where most of the supply does not meet any demand. That perception has been, for decades, dominating the urban housing provision programs and national policies, such as the New Cities which have failed to realize their target populations, reaching 27% of the target at best and only 3% at worst, despite the huge public investments poured into building them (Tadamun, 2015). This is also manifested in the governmental attempts to demolish informal settlements and absorb low-income demand through the construction of low-cost housing. If anything, such policies are elitist because they are built upon a top-down idea of demand; one that views demand for low-income housing as merely a numerical value which can be shifted and relocated, without any hurdles. People do not live in informal settlements by accident. Families choose to live in these areas because the cost of living is minimal, the sense of community is noticeably high, and the feeling of responsibility for collective action is quiet powerful. And yet, not every informal house translates into unmet demand. Some of the informal housing units are of better quality than formal housing units, including those built by private and public sectors. Moreover, because not all households are of the same income level, different types of demand are likely to emerge out of informal settlements; some may be for low-income households, while others may be for middle-income earners. All of these aspects should be considered before jumping to interventions.

It can be seen that understanding and effectively measuring housing demand in Egypt are crucial to move towards a positive housing policy change. So, how is housing demand measured in Egypt? As far as we know, the only official estimation of housing demand does not outlay its methodology, providing us only with a number of housing units. Other institutions that have studied housing demand have either focused on certain aspects of it, or have simply conducted a survey to assess people’s perception of the housing market. There is no published need and demand study of housing in Egypt – a shortcoming that needs to be immediately addressed.

What do numeric estimations tell us about Egypt’s housing demand?

There is an apparent discrepancy in the numerical estimations of housing demand in Egypt.

The Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS) does not collect data on total housing demand. Nonetheless, according to the World Bank’s 2008 “Framework for Housing Policy Reform in Urban Areas in Egypt”, 70-80% of Egypt’s population lies in the “low, moderate, lower-income” stratum (World Bank, 2008a). This stratum, according to the World Bank, has an annual housing need that lies between 165,000 and 197,000 units (World Bank, 2008a). Assuming this is an annual estimate, one can deduce that the total demand for Egypt’s housing demand is somewhere between 235,714 and 281,428 housing units.4 The World Bank stresses that theoretically there is no shortage of supply, because yearly population growth (1.9% during the of 1986 to 1996 inter-census period) has been less than rate of annual housing supply (3.6%) (World Bank, 2008a). The World Bank states that in the following 1996-2006 period, annual growth of housing stock was 2.8%. By mid-2005, the total number of urban households was around 6.84 million, whereas the total number of housing units in urban areas was approximately 9.49 million units. (World Bank, 2008a). Yet in a different paper, published in the same year, the World Bank placed the average yearly demand at 300,000-400,000 housing units in 2008-2023 (World Bank, 2008b). Based on the two papers published by the World Bank, Egypt’s approximate housing demand sits within a range of 235,714 to 400,000 units per year, revealing a huge numerical discrepancy even according to the same source.

On the other end of the spectrum, a different set of researchers estimate housing demand figures at much higher rates than the abovementioned approximations. In 2005, Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) referred to estimates by the Middle East Ratings and Investors Service (MERIS), an investors’ service that provides credit rating services in Egypt and other countries in the region, that Egypt’s yearly housing demand was approximately 750,000 units per year.

Some researchers have also estimated yearly demand at figures much higher than the above. Yahia Shawkat (2013) estimates yearly housing demand at 870,000 units per year in the period between 2000 and 2011, assuming that 2.8% of the urban population has a housing demand. To calculate housing shortage in Egypt, Shawkat subtracted yearly annual supply (estimated at 295,000 units including the supply of informal housing) from the annual demand (870,000), thus estimating yearly shortage at 575,000 units – approximately double the housing units produced annually. To get a more accurate figure, he subtracted the yearly number of units blocked from the market (mostly because they are not offered for sale) from the total number of yearly supply, estimating actual total shortage at 663,000 units per year (Shawkat, 2013). Furthermore, Shawkat estimated housing supply shortage in response to “urgent demand” (such as the demand created by newly formed families, which is 41.6% of the total demand) at 194,000 units per year. Shawkat and USAID’s estimations are so different from the World Bank’s to the extent that concerning certain issues (for example: the question of shortage versus over-supply) they are in fact completely contradictory to one another.

The problem with the above-mentioned figures is not just the vast discrepancy between the lowest and highest housing demand estimates (235,714 units versus 870,000 units), but also the fact that they do not provide useful information for policy-makers, developers and investors. Calculating yearly housing demand is important only in as far as it provides a crooked, hurried picture of the housing market. However, studied exclusively, these figures say little about unmet versus future demand, variations of demand across different regional and sub-regional levels, latent demand (demand that is non-existent at the moment, but carries the potential to appear in the future) versus effective demand (demand currently existent), and income-level vis a vis housing demand. Only dealing with housing demand from a purely numerical perspective is also problematic because it does not specify urban housing demand, which usually makes up the bulk of total housing demand. In other words, practically, numerical estimations of housing demand carry little value and may in fact be misleading if they do not account for future changes of demographics and economic fluctuations.

Qualitative approach that goes beyond the numbers

In 2006, The Technical Assistance for Policy Reform II (TAPR II), a USAID project, was delegated by the Minister of Investment to conduct a housing demand study covering the urban area of Greater Cairo. The survey (GCHS) resulted in an improved understanding of the issue, however, it was only providing insights about housing in Greater Cairo, and couldn’t be generalized for other towns and cities in Egypt. Therefore, the 2008 Egypt Housing Survey (EHS) emerged as an expansion of the GCHS, requested by the Ministry of Housing, Utilities and Urban Development and the Ministry of Investment. The sample survey of 21,580 households was designed to produce statistically representative results for all of urban households in Egypt – except for those in the Frontier Governorates. The EHS was the first survey of its kind during the previous 30 years (TAPR II, 2008) and the last published one up till the moment.

The analysis of the EHS offers the most comprehensive approach to study demand in a qualitative sense, providing information on what urban dwellers look for when they seek housing units. It addresses Egypt’s housing market behavior and looks at a wide range of socioeconomic factors that affect Egypt’s housing demand including: market exchanges, movement of households and migration, how households obtain information on the housing market, new versus old rent, information regarding Egypt’s informal housing sector and perceived value of units. It also includes information on the population and the expressed demand preferences including: percentage of demanders, where is demand concentrated, reasons behind demand, demand for units versus demand for lands, demand by location, tenure, how to finance purchases, characteristics of demanded units, and preferences for government-supported housing programs. It also contains information on Egypt’s occupied housing stock including types, sizes and number of rooms, amenities, tenure status and security, and satisfaction. The last two parts of the survey were on neighborhood characteristics and households characteristics.

The EHS identified only 1,735 demanders – individuals who were actively searching for houses- among the sample. The results showed that 46% of demanders are seeking a house to get married, 16% to bigger unit, 15% for reasons related to securing tenure, and 10% were nuclear families wanted to live independently. The results also revealed that 14% of demanders had been searching for five or more years. The majority of demanders were aged in their twenties and thirties, and 98% of them were males.

Only 4% of demanders were seeking serviced land to build upon, while the rest were looking for built units, mostly (97%) for apartments. For all apartment demanders, the desired apartment size was about 80m2 and 63% of them wanted finished apartments.

Interestingly, the sample showed that 6% of all demanders were looking for housing units in another governorate. Moreover, more than half of demanders (52%) were searching in the same neighborhood (the rest were searching in the same city or another city in the same governorate). Despite widespread perception, that data indicates a low rate of mobility between different urban centers. The reasons due to which demanders preferred certain areas were highly related to economic factors. For instance, 66% agreed that affordability of the unit is a decisive factor, 53% mentioned proximity to work and 25% the availability of transportation. Social networks were also very important as 56% of demanders expressed their tendency to choose a location due to its proximity to relatives and friends.

As for financing preferences, 52% of demanders were saving to acquire housing, only 20% were having dealings with banks and 29% expressed their intentions to obtain bank loans to finance housing.

However, the study clearly distinguished between the “expressed demand” that reflected the surveyees’ perceptions and preferences, and the real demand behaviors. They are not necessary equal (TAPR II, 2008). The study also recommended caution in generalizing the results due to the small sized sample. Yet, such a study provides important insights into the demanders’ characteristics and preferences that go beyond numeric calculation, and thus can lead to improvements in housing policies and programs.

Learning from global experiences

All previous studies aside, Egypt still needs a comprehensive national need and demand study of housing. If we took the “Housing Conditions and Demand for Housing in Urban Ethiopia” as a possible guide, determining overall demand will require: Firstly, studying the unmet demand by analyzing both the housing stock with the purpose of determining which housing units are inadequate (under-standard) and need renovation or replacement, and assessing levels of over-crowdedness and cohabitation that create a need for the construction of new housing units. Then, assessing future demand based on an assessment of future demographics. Adding the two estimates, unmet demand and future demand, can give us a rough numeric estimate of overall demand – including demand for renovation.

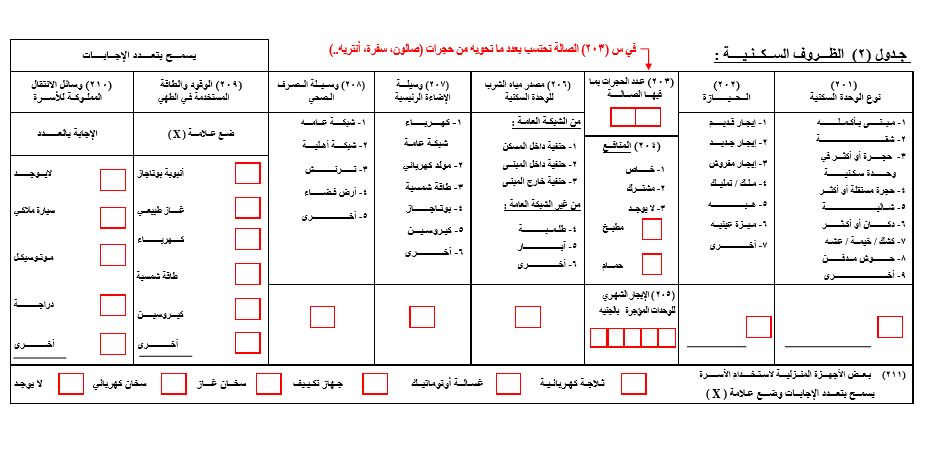

Most of the data on the characteristics of existing housing stock are already available through Egypt’s “Census of Population, Housing and Establishments” conducted by the “Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics” (CAPMAS). The national survey takes place every 10 years (the last published one was the Census of 2006, and the Census of 2016 is expected to be released sometime this year). The ‘Household & Housing Characteristics Questionnaire’ used for the survey collects data on the type of the housing unit, tenure status, access to water and sewage, number of rooms, rent and other housing conditions for each household. Furthermore, the survey also includes a “Register of Buildings and Their Components” that collects data on the age of the building, construction materials and its connectivity to utilities’ networks among other components.

The table on housing conditions in the ‘Household & Housing Characteristics Questionnaire’ of the 2016 Census. Retrieved from: http://www.capmas.gov.eg/Pages/Forms.aspx?page_id=5033

The challenge in this case will be determining which existing housing stock to be considered as an unmet demand – for either under-standard or overcrowded units, and how to identify the standards/thresholds by which those classifications can be made.

Egypt’s Unified Building Law (Law no. 119 for 2008) states the formally accepted standards to measure housing units’ adequacy, even though, comparing the legal standards to the reality of housing conditions in Egypt will lead us to the fact that there are too many housing units that do not fit these standards, and likewise if we used the international standards, it may not be very realistic, considering the socio-economic context in Egypt and decades of neoliberal policies that dominated land management and housing provision in Egypt. Translating every off-standards unit into an unmet demand can easily give us a misleading indicator. However, creating such an index will need multidisciplinary studies that are geographically distributed all over Egypt, to determine the exact criteria to measure unmet demand. Maybe we will need to break each classification into narrower categories and consider only the highest as unmet demand.

Future demand, on the other hand, depends on natural and social demographic changes. Calculating future demand is not by any means the focus of this paper, nonetheless, we need to highlight a few facts that can give us some insight into the nature of this future demand. With regards to natural demographic changes, the Egyptian population grows at an average rate of 2.4% according to the Central Agency of Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS, 2016). This is a high rate comparing to other developing countries. Egypt’s population is now 92,434,491 5, and it rose by two million persons in the course of only one year (CAPMAS, 2016). 43.1% of the population are living in urban areas, and the percentage is expected to increase. Additionally, a large number of new households will likely be young, and in search for jobs, which could denote a high level of housing demand for urban areas. However, this demand is likely to be offset by a number of factors including low levels of income, and increasing poverty rates in urban Egypt. In other words, if future demand is to follow previous patters of housing demand, the bulk of it would be latent, while only a small fraction would be effective.

It also is worth noting that most of Egypt’s urban population growth occurs in the Nile Valley and Delta region. Therefore, it is likely that future population growth will follow the same pattern, especially when the desert cities are not attracting any significant population. We must also acknowledge that the fastest growing population within Egypt is in informal settlements. In fact, comparatively, Cairo’s informal inhabitants grow at an average of 2.57% per year, while Cairo’s planned areas population grows at an average rate of 0.40% per year (World Bank, 2008b)6. It is difficult to predict whether this directly translates into demand for low, and mid-income housing as households in informal areas are more likely to have high levels of latent demand that is not translated into effective demand due to financial constraints.

Social demographic changes in urban Egypt are not of major importance to urban Egypt’s future housing demand as the Egyptian population is largely immobile, and most of the migration is urban-to-urban (World Bank, 2008b).This immobility is mostly due to high real estate prices accompanied by low purchasing power capacities. As such Egypt’s future housing demand is mostly dependent on natural demographic changes, rather than on social demographic dynamics.

Conclusion

Housing is a social good, not only a traded asset. Therefore, predictions for housing demand should reflect the reality of the housing market and its complexities rather than depending on theoretical numerical calculations. In Egypt, changing popular perceptions about housing demand is the first step towards an effective policy change. Demand cannot be summarized into a number of needed units, and thus the answer to it should not be by only building an equal number of units. The characteristics of households, their purchasing power, their ability to be mobile and also their preferences on one hand, and on the other hand the specifications of the housing supply (such as availability, affordability and location of housing units, and the expected changes in prices) all together determine housing demand. Factors and Processes of urban expansion, land management and service delivery are also highly relevant.

More importantly, tenure for demanders is a major factor. Researchers and policy makers must distinguish between demand for property ownership and demand for rent.

There are huge gaps of research regarding housing demand in Egypt. More needs to be done to address the very nature of the state economy which is projected in the housing sector. Housing demand in Egypt is determined by supply and demand economics and is also related to the urban development and expansion patterns. Neoliberal policies that do not take into account the needs of the less affluent will eventually lead to the emergence of more under-standard informal houses, and a large amount of unmet need. Despite all the attempts to build a million or more of new housing units, if the policy makers do not understand the complexity of demanders’ preferences and abilities, the same imbalance between demand and supply will remain an issue.

Bibliography

Abelti, Gebeyehu, Marco Brazzoduro, and Behailu Gebremedhin. 2001. Housing Conditions and Demand for Housing in Urban Ethiopia. Addis Abba, Ethiopia: Central Statistical Authority (CSA), Institute for Population Research – National Research Council (Irp-Cnr). https://www.irpps.cnr.it/etiopia/pdf/Housing_Conditions_and_Demand_for_Housing.PDF.

Ballesteros, Marife Magno. 2001. “The Dynamics of Housing Demand in the Philippines: Income and Lifecycle Effects.” Discussion Papers, Philippine Institute for Development Studies 2001 (15): 2001–15.

BC Housing. 2010. “Housing Needs and Demand Study.” https://www.bchousing.org/research-centre/library/tools-for-developing-social-housing/housing-needs-and-demands-study-template.

Blumenfeld, Hans. 1944. “A Neglected Factor in Estimating Housing Demand.” The Journal of Land & Public Utility Economics 20 (3): 264. doi:10.2307/3159254.

Chappelow, Jim. 2019. “Learn about Law of Supply and Demand.” Investopedia. Accessed November 18, 2019. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/l/law-of-supply-demand.asp.

Dorling, Daniel. 2015. All That Is Solid the Great Housing Disaster. London: Penguin Books.

Follain, James R., and Emmanuel Jimenez. 1985. “Estimating the Demand for Housing Characteristics: A Survey and Critique.” Regional Science and Urban Economics 15 (1): 77–107. doi:10.1016/0166-0462(85)90033-x.

Holmans, Alan. 2013. “New Estimates of Housing Demand and Need in England, 2011 to 2031.” Town & Country Planning Tomorrow Series Paper 16. https://www.cchpr.landecon.cam.ac.uk/Downloads/HousingDemandNeed_TCPA2013.pdf.

Boumeester, H.J. 2011. “Traditional Housing Demand Research.” In Measurement and Analysis of Housing Preference and Choice, edited by Sylvia Jansen, Henny Coolen, and Roland Goetgeluk , 27–55. Springer.

Kimmons, Ronald. 2016. “What Is the Difference Between Demand and Effective Demand?” Houston Chronicle. October 26. https://smallbusiness.chron.com/difference-between-demand-effective-demand-17957.html.

McKie, Anna, Erin K. Wilson, Roger Smyth, Matthew Reisz, Suzanne Franks, John Gilbey, and Jack Grove. 2015. “All That Is Solid: The Great Housing Disaster, by Danny Dorling.” Times Higher Education. October 23. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/books/all-that-is-solid-the-great-housing-disaster-by-danny-dorling/2011337.article.

Salford City Council. 2012. “Strategic Housing Market Assessment 2012.” https://www.salford.gov.uk/housing/strategies-policies-and-partnerships/housing-research/strategic-housing-market-assessment-2012/.

Shehayeb, Diana, and Marion Fischer. 2009. “Advantages of Living in Informal Areas.” In Cairo’s Informal Areas Between Urban Challenges and Hidden Potentials Facts. Voices. Visions., edited by Regina Kipper, 35–44. Cairo: GTZ.

Sims, David, Hazem Kamal, and Doris Solomon. 2008. “Housing Study for Urban Egypt.” https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNADY276.pdf.

TADAMUN. 2015. “Egypt’s New Cities: Neither Just nor Efficient.” December 31, 2015. http://www.tadamun.co/egypts-new-cities-neither-just-efficient/?lang=en#.Xfu8XNZKjOQ.

Thompson, Warren S. 1937. “Population Growth and Housing Demand.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 190 (1): 131–37. doi:10.1177/000271623719000115.

World Bank. 2008a. “A Framework for Housing Policy Reform in Urban Areas in Egypt: Developing a Well Functioning Housing System and Strengthening the National Housing Program.” Economic and Sector Work Studies. Washington, DC. June 1. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/7955.

World Bank. 2008b. Egypt-Urban Sector Update. Washington, DC: World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/749891468023382999/Urban-sector-update

1. The law of demand states that if all other factors remain constant, the higher the price of a good, the less quantity demanded for that good. Conversely, the law of supply states that if all other factors remain constant, the higher the price a good, the more the quantity supplied for that good (Heakal, n.d.). The reason is because the higher the price, the more revenue suppliers will make. The law of supply also predicts a surge in prices of goods when there is a shortage of supply (when quantity demanded exceeds quantity supplied, and then prices of goods will increase).

2. Equilibrium refers to a condition in the market, where suppliers are supplying all the goods they have produced, and consumers are getting all the goods they are demanding.

3. The study was based on two different thresholds to evaluate overcrowding. The first was to consider house unit with three inhabitants per room as overcrowded, while in the second the ratio was two inhabitants per room. Thus, the study produced two overcrowding estimates on the country level, the regional level and for each town.

4. This number was calculated by multiplying (100) by (165,000) divided by (70) first, and then repeating the same calculation for (165,000) units.

5. Retrieved from: http://capmas.gov.eg/,Thursday 7 February 2017 12:45 PM Cairo time.

6. Notice that since the data is from 2008 we cannot confirm the extent to which it is outdated today.

Featured image by: DiGiTaL_SiN, Edited by: TADAMUN

Comments