Cairo 2050 Revisited: The Role of International Organizations in Planning Cairo

When Cairo 2050 started to generate controversy among urban observers and citizens much of the criticism was directed towards the General Organization for Physical Planning (GOPP). While it is true that the GOPP is the main party credited with bestowing Cairo 2050 upon Egyptians, it did not undertake this effort on its own. Rather, there were quite a few international organizations involved in the development of this plan. But what role did these organizations play? And what impact did they have? This cannot be understood in isolation of the historical role they have played in Cairo for the past several decades.

International organizations are no stranger to Egypt’s development scene, as they have poured millions into development projects in Egypt since the 1960s. For example, between the 1970s and 1990s Egypt received around USD 1.5-2.5 billion per year in economic aid and credits. During the 1980s, around 80% of Egypt’s public investment came from external funding, and between 1975 and 2002, around USD 26 billion were provided by Washington alone as economic assistance (not to mention another USD 28 billion in military aid) (Dorman, 2013). The donor certainly hopes that its financial investment shapes technical assistance, institutional reform, and policy recommendations (see for example, USAID’s 2004 Report “The Cost of Not Privatizing: An Assessment for Egypt.”)

This funding has been spread out over countless development projects in various sectors, but several have been focused on Egypt’s urban development. This article will review the role foreign organizations have historically played in Cairo’s planning and urban development. However, it must be stated that the intention of this article is not to pass judgment on the impact of international organizations. In a multi-faceted situation such as the one that will be described below, any simple judgment runs the risk of being reductionist unless accompanied by an in-depth academic study that is beyond the scope of this article. Rather, the aim of this article is merely to provide an overview of the different ways in which foreign agencies have intervened in planning Cairo.

Beginnings: Urban Planning Pre-International Involvement

The first attempt to master-plan Cairo was carried out in 1956 by a number of Egyptians trained in the West (El Shakry, 2006) and they adopted certain trends in urban planning that were popular in the West at the time such as containing the city to reach an optimal size, but not expand beyond it (Serageldin, 1985). Thus, the plan set Cairo’s maximum population at 3.5 million and any growth beyond that would be directed into new free-standing satellite cities built in the desert (El Kadi, 1992). However, the government never officially approved the plan and by 1960 Cairo’s population had already passed the 4 million mark (Abu-Lughod, 1971).A second attempt was put forth in 1965 by the High Committee of Greater Cairo (Raymond, 2000), and created industrial poles at Helwān, Shubra Al-Khayma, and Imbaba (El-Batran and Arandel, 1998), which, ironically, served to increase the attractiveness of Cairo while also putting in place the infrastructure, employment opportunities, and services conducive to the growth of informal settlements (Dorman, 2013).

The third planning attempt around 1970 – also by the High Committee of Greater Cairo – continued the main themes of the unapproved 1956 plan, to limit Cairo’s population size – by this time at 9.5 million – and absorb excess growth into new desert cities. Containment would take place through the construction of a ring road, forming an urban cordon around the city (Sims, 2012).

The Arrival of International Organizations to Egypt’s Urban Sector

It is around the late 1970s that international organizations started exhibiting interest in the urban sector. This was closely linked to the 1976 UN-Habitat conference in Vancouver which “played an important role in changing attitudes with respect to human settlements and urban development” (Milbert, 2000). In Egypt this was preceded by the establishment of the General Organization for Physical Planning in 1973. One academic has suggested that the GOPP was created to function “mainly as a donor client” as new alliances with the West meant aid started flowing into Egypt (Dorman, 2007). By 1978 the GOPP had partnered with the United States Agency for International Development USAID, the World Bank (WB), and the German Technical Cooperation agency GTZ (today renamed to GIZ) to launch major urban development projects.

According to WB project documentation, it decided to undertake its first urban sector project “in response to a request by the Government [of Egypt].” Until 1978, most of the Bank’s projects in Egypt were focused on the agriculture sector. But in June 1978 it announced the approval of its first urban development project in cooperation with the Egyptian government, with the objective to: “provide shelter, employment and urban services for the lowest income groups at costs they can afford, thus eliminating the need for direct public subsidies and permitting the project to be replicated on a larger scale.” The project also aimed to provide freehold titles for the land in the upgrading areas – which belonged to the governorates – conditional on the payment of certain plot charges.

Such an approach to urban upgrading was a departure from the traditional government approach thus far, as it constituted a shift from trying to build new homes in new cities to absorb excess growth, towards upgrading existing low-income housing. If this approach had been fully adopted by the Government of Egypt (GoE), it could have potentially altered the national urban planning approach. The project was meant to function as a pilot that the government would later replicate at a national scale. However, according to one study, the project faced resistance from government officials who preferred to conserve the government’s interventionist approach to providing housing and worried that upgrading informal areas would signify its acceptance of an illegal act. Another complicating factor is that much of the land on which informal dwellers had settled was owned by the governorates, who resisted the idea of providing dwellers with legal title to the land. In light of all this, the project failed to permanently change the Egyptian state’s housing policy and it “resumed its policy of building finished housing units particularly in the new towns” (El-Batran and Arandel, 1998).

As for the GTZ, its role was to provide technical assistance for the planning and development of one of Cairo’s main new satellite cities Al-ʿUbūr. However, this project also faced many hurdles, primarily the existence of various parties who hold some stake in the land on which the city would be built.

The Egyptian/German Al-ʿUbūr Master-Plan Study Group published a report in 1980 detailing the difficulties they faced in planning the area due to the involvement of such parties who often had conflicting interests (or at least interests that conflicted with the project’s intended outcome) such as the Cairo governorate, the Arab Contractors, and a military-dominated agricultural cooperative (Sims, 2011). Ambiguity regarding who had the authority to manage Egypt’s land is one that goes far beyond this particular project, but represents one of the many hurdles that have impeded the success of the “new towns” approach. Secondly, the government’s approach relied on heavy subsidies to attract residents – which proved extremely expensive – and despite all investments in and attention toward the new towns, still failed to create a viable alternative for the type of residents who are attracted to informal areas, and thus failed in its mission to attract a significant population (Dorman, 2007). Due to such hurdles among other factors, the planned satellite cities were unable to absorb the excess population they were meant to, despite financial and technical assistance from international organizations.

By 1980, the Egyptian government saw the need to develop yet another plan to redefine its urban strategy (Dorman, 2007). In 1981, the GOPP commissioned another international organization – the Institut d’Aménagement et d’Urbanisme de la Région d’Ile-de-France (IAURIF) – to support the development of a new Cairo master-plan. IAURIF is a foundation chaired by the chairman of the Regional Council of the Ile-de-France region and was established by decree in 1960 to oversee the planning of the Paris region. IAURIF submitted its study in 1982, in parallel with a National Urban Policy Study that USAID completed around the same time.

The USAID study advised against the government’s approach of setting up free-standing new towns and instead proposed establishing new communities at Cairo’s Eastern and Western peripheries rather than trying to direct growth away from Cairo which did not seem to be working. Similarly, the IAURIF study emphasized Cairo’s high economic potential that any new city would have to match in order to attract residents. It argued that the new cities had failed to attract a significant population, despite their highly subsidized construction because they could not match the economic opportunities that Cairo offered. Based on this, the study proposed focusing on new communities located around Cairo’s extant urban agglomeration rather than establishing new cities outside it. President Husni Mubārak formally approved this recommendation in 1983 and since then international organizations have been involved in the development of these new urban communities (NUCs). In light of this approach, out of the twenty-two new cities/new urban communities1 that exist in Egypt today, only New Cairo, 6th of October, 10th of Ramadan, Al-Shurūk and Badr cities received attention in the plans that involved international organizations.

The NUCs were meant to target lower- and middle-income groups as a way to both limit the growth of Cairo’s population while also providing an alternative to residents who would be tempted to settle in informal areas. However, this policy did not achieve its goal and the result has been “nearly empty new towns” (Fahmy and Sutton, 2008), and the expansion of high-end gated communities – or “luxurious housing” according to the Ministry of Housing in 1996 (qtd. in Dorman, 2007) – as land in these new towns was repeatedly sold to investors.

The establishment of new towns on Cairo’s eastern-western periphery embodied one of the main themes promoted by the IAURIF study. The other main theme urged cordoning off and limiting Cairo’s urban agglomeration by constructing a ring road. The 1970 master-plan had already proposed the ring road but the IAURIF study underscored the urgency for this “most important immediate action” (Dorman, 2007). However, to avoid the risk that the ring road would lead to further informal urbanization along the areas around it, the study proposed constructing the road “along only three-fourths of its circumference (73 kilometers) so as not to encourage the urban development in agricultural zones” – particularly the arable lands around Giza city (Raymond, 2000).

IAURIF’s “master-scheme” was formally approved by then-president Mubarak in March 1983, and based on its suggestions construction of the ring road began a few years later (Dorman, 2007). The plan and its assumptions, however, failed to limit the informal urbanization of agricultural lands, as urbanization of the surrounding areas almost tripled after the ring road was opened for business (Piffero, 2009). The road was supposed to pass through Giza, quite close to the Pyramids, but this plan was halted after UNESCO intervened, citing the negative impact of construction on such an important world heritage site. The IAURIF plan functioned as Cairo’s official master-plan until the 1990s, even though most of its recommendations were not implemented in the way initially proposed (more details about this can be found in Dorman, 2007, pp.200).

International Organizations and Cairo 2050

As Egypt entered the new millennium, the Egyptian government began efforts to undertake a “visioning” exercise for the city and thus Cairo 2050 was born. The Cairo 2050 plan was a joint effort established around 2007 between the GOPP, UNDP/UN-Habitat, the World Bank, the GTZ, and Japanese foreign aid agency JICA, and championed by Gamal Mubārak the son of Egypt’s President at the time.

To say Cairo 2050 was controversial would be an apt description – perhaps even an understatement. As information about the plan became more publicly available, residents and urban observers accused it of serving the interests of the elite and attempting to purge Cairo of the poor through forced evictions. They also critiqued the process through which the plan had been developed in a secretive, top-down manner without public hearings and public access to the data and analysis that were its foundation. It is interesting, to say the least, that a number of international organizations developed and contributed to the report, even though every single one of them espoused a commitment to human rights, social justice, and public participation.

The GTZ classified informal areas within the GCR and proposed a development intervention for each type, as part of the Cairo 2050 master-plan. They called for a participatory approach, in cooperation with the local governments of the three concerned governorates (Cairo, al-Gīza and al-Qalyūbiyya). UNDP/UN-Habitat developed and managed the Cairo 2050 plan by recruiting consultants, conducting workshops, procuring equipment, creating a communication strategy and – perhaps most importantly – promoting transparency and ensuring the involvement of key stakeholders (Government of the Arab Republic of Egypt and the United Nations Development Programme Project Document for the Strategic Urban Development Plan for Greater Cairo Region, 2007).

The World Bank (WB) was to prepare feasibility studies for the project’s priorities at the local level (Government of the Arab Republic of Egypt and the United Nations Development Programme Project Document for the Strategic Urban Development Plan for Greater Cairo Region, 2007). Throughout this period the WB published a number of relevant studies although it is unclear to what extent they were directly part of the Cairo 2050 project. This included a public land management strategy, a report on housing supply and demand published by USAID in 2008, a framework for housing policy reform published by the World Bank in 2008, a 2008 World Bank report on mortgage-linked housing subsidies, and an “Urban Sector Update” for Egypt in 2008, among others.2 The Update provided a set of key recommendations on how to improve government responses to urban challenges, including:

- Re-evaluating the desert development strategy and re-directing attention to existing cities. All attempts to re-direct growth towards new desert cities had failed with the exception of a few new towns that managed to attract residents, especially around Greater Cairo. Thus, the Bank suggested conducting an in-depth assessment of the actual potential of the new towns and how to manage growth in existing cities.

- Developing planning and building standards appropriate for affordable housing. According to the report, the high-standard low-density design prevalent in the new towns was making housing financially inaccessible to the low-income groups the government purported it was targeting. Thus, the Bank suggested designing specific standards for new popular neighborhoods that would enable affordable housing and attract the targeted low-income population.

- Expanding local government’s control over asset management and enhancing their ability to pursue sustainable financing mechanisms. This recommendation was based on the perceived need to accelerate decentralization and bureaucratic reform, as well as the importance of enabling local governments to identify investments, mobilize resources, leverage public assets, and capture land value increments.

During this time the Bank was also “advising the government on affordable housing policy and subsidies” and providing technical assistance on “land registration and mortgage market development” among other forms of support (World Bank, 2008).

The World Bank’s recommendation to encourage cost-recovery and utilize land values is important to analyze and historicize. In the government’s earlier major interventions in informal areas dating back to 1993, cost-recovery was not part of the approach at all.3 Their plans for upgrading included the provision of infrastructure and services, financed entirely by the Egyptian government, without provisions for cost recovery. But cost-recovery has been a consistent mantra in many international interventions in Egypt’s urban planning and development. Over the past several decades, foreign organizations – especially the World Bank and USAID – have promoted and encouraged lower housing subsidies, higher utility tariffs, selling land titles to informal dwellers, and lowering urban design, construction and upgrading standards to increase affordability. But perhaps most notable is the push towards cost-recovery by creating a “self-sustaining process whereby the recovery of capital costs from upgrading would, in part, finance subsequent phases of upgrading – independent of the Egyptian state’s centralized budgetary process” (Dorman, 2013). This was exactly the financial system adopted by the Informal Settlement Development Facility (ISDF) – established in 2008 – which relied on a revolving-fund mechanism that extracts capital from upgrading areas on valuable land to cover the cost of improving other areas that don’t have the same financial potential.4

This model has been critiqued as one that poses a challenge for ISDF’s work as it can negatively impact the upgrading process by placing funds in the control of a centralized body (ISDF) rather than in the hands of the local executive government entities. Furthermore, this model provides incentive for ISDF to prioritize upgrading of areas that lie on valuable land, and makes selling the land or development rights to private investors a much more lucrative option than giving those rights to the residents.

Perhaps the most substantial input into the development of the plan’s content came from JICA. JICA was responsible for updating the most recent Cairo master-plan, which was the 1997 GOPP-modified version of the IAURIF study. The updated master-plan proposed by JICA would then provide the main input into the content of Cairo 2050. JICA’s “Strategic Urban Development Master-Plan Study for Sustainable Development of the Greater Cairo Region” was published in 2008. It showed three possible scenarios for future growth of the Greater Cairo Region and proposed the third scenario as “the most preferable future growth pattern” (JICA, 2008). Thatscenario was based on controlling and limiting future urbanization and population control, and directing them towards the new urban communities on Cairo’s periphery. Based on the study’s calculations the new communities could absorb approximately 4.2 million of the area’s population growth. In other words, the proposed approach was almost the exact repetition of the original IAURIF plan, only slightly modified to incorporate updated population projections. To attract these residents, they suggested increasing the housing supply, improving living conditions in informal areas, promoting business, industrial, and tourism zones, strengthening transport, conserving natural resources, and creating green spaces.

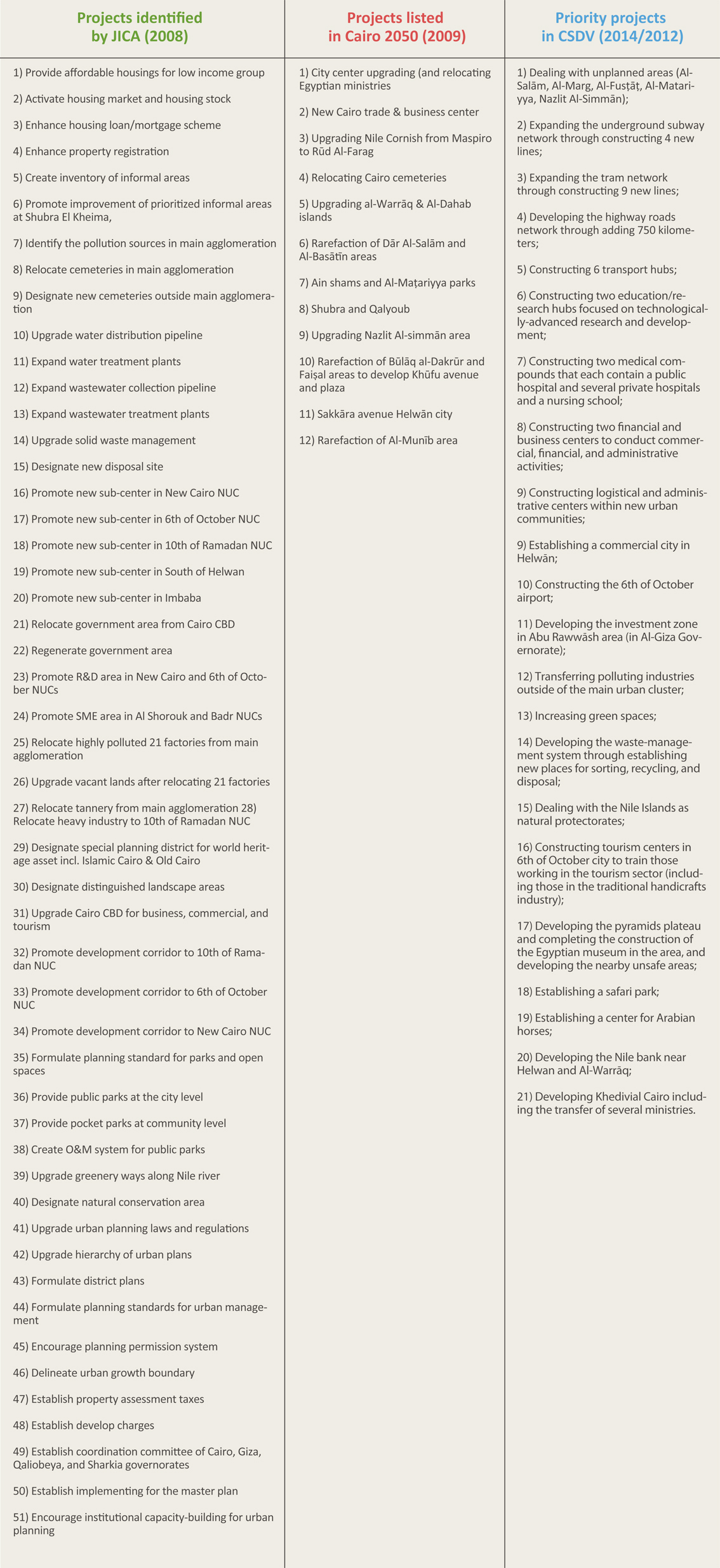

These goals were then grouped into “sub-sector strategies” which were: providing housing supply for various household groups, improving living environment for informal areas, promoting new business and commercial areas, promoting industrial and R&D areas, promoting tourism areas, vitalizing the new urban communities, promoting transport-oriented urban development area, conserving agricultural lands and natural resources, promoting open and green areas, strengthening management of the urban growth boundary, and improving the implementation system of the master-plan. These were, in turn, translated into fifty-one projects targeting urban management, living conditions, infrastructure, and institutional development, to be implemented over the short term (next five years), medium term (next ten years), and long term (next twenty years).

A simple comparison between the projects proposed by JICA, the projects listed in the 2009 version of Cairo 2050, and the priority projects that made it into the latest Cairo Strategic Development Plan (CSDV), from 2012/20145 shows that a few themes have been consistent throughout the three versions. The following in particular exist in all three versions:revitalizing downtown Cairo and relocating the ministries to New Cairo, relocating Cairo’s cemeteries, further developing Cairo’s new communities (particularly 6th of October), and investing in areas with touristic potential (especially Khūfu Avenue that connects Nazlit Al-Simmān to the more central Sphinx square, the area of al-Maṭariyya in North East Cairo, and the Al-Fusṭāṭ area in old Cairo).

The CSDV plan being promoted by the GOPP today is a revised version of Cairo 2050, but many of the same elements remain. The current effort to revise Cairo’s strategic planning is being led by the GOPP with support from UNDP and UN-Habitat. It is unclear to what extent the World Bank, JICA, and GIZ are still involved, as neither have any projects on their websites explicitly related to current planning efforts, and the GOPP only mentions “a number of international and local experts in various fields.” According to UNDP’s website, it is responsible for the project’s outreach and stakeholder communication, creating a National Urban Observatory, and preparing detailed studies for the cemeteries area, al-Maṭariyya area, al-Warrāq island, and downtown Cairo. It also mentions the development of strategic mater plans for the Giza Pyramids / Nazlit Al-Simmān area, as well as the area of Al-Fusṭāṭ. The UN-Habitat website doesn’t provide many details, but rather simply states that it is supporting GOPP in preparing the plan for the region using a “decentralized and integrated approach.”

Conclusion

If you tell the average Egyptian on the street about the heavy involvement of international organizations in Egypt’s development scene for several decades, the response might be: Why haven’t we seen any impact of this involvement? Such a sentiment may not be entirely accurate given the number of infrastructure improvements particularly in regards to water, sanitation, and transportation6. However, in regards to the impact on urban planning, it may not be that far from the truth. Since the 1970s, every single plan developed for Cairo has promoted the same themes: redirecting growth away from the city center and containing the city’s growth through a ring road. The JICA/Cairo2050/CSDV plans took the additional step of creating an unrealistic – albeit beautiful – grand vision of Cairo as “global, green, and connected.” It retained the theme of relying on new towns while also promoting green spaces, tourism, and an investor-friendly city that would entail the forced eviction of millions of low-income Cairenes and violate their right to adequate housing and their right to the city. But what exactly is the role of international organizations and is it fair to expect substantial changes as a result of their interventions? In other words, is it fair to blame them for misdirected urban plans and projects?

As demonstrated above, international organizations have played various roles in Egypt’s urban planning, usually falling along the lines of donors, implementers, or advisors/consultants. Sometimes their role has been to provide funding, other times it has been to implement projects and provide examples of best practices, and other times their role has been to receive funding from government agencies in exchange for providing technical advice and support. When they are merely providing advice, there is no way they can force the government to take their recommendations, and thus one cannot reasonably credit or blame them for the outcomes. The issue lies mainly in the fact that regardless of the role they are playing, oftentimes they end up taking part in – or at least indirectly give their blessing to – practices that contradict their principles.

For example, many international organizations have been vocal in advocating for the democratic management of the city, but when it comes to implementation in the real world the situation is much more complex (something confirmed by the fact that the lack of transparency and participation was one of the main criticisms leveled against Cairo 2050). Sometimes international organizations promote positive ideas and are ignored, and other times they promote ideas that are implemented but ultimately end up hurting the poor. Often international organizations have limited power in actually influencing decisions made by the Egyptian government, and the result is that they end up contradicting many of the principles they espouse. Such issues are tied to wider arguments about the effectiveness of foreign aid in general. In the end, it is not really a question of the so-called chaos of the city or the intentions of foreign organizations, but rather a question of whose interests prevail when planning Cairo.

References:

Abu-Lughod, Janet. Cairo: 1001 Years of the City Victorious. 1st ed. Princeton Studies on the Near East. Princeton University Press, 1971.

GTZ Egypt Participatory Development Project. Cairo’s Informal Areas Between Urban Challenges and Hidden Potentials: Facts. Voices. Visions. Cairo: Cities Alliance, 2009.

Dorman, W. Judson. “The Politics of Neglect: The Egyptian State in Cairo, 1974-98.” PhD, School of Oriental and African Studies, 2007.

Dorman, W. Judson. “Exclusion and Informality: The Praetorian Politics of Land Management in Cairo, Egypt.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37, no. 5 (2013): 1584–1610.

El-Batran, Manal, and Christian Arandel. “A Shelter of Their Own: Informal Settlement Expansion in Greater Cairo and Government Responses.” Environment and Urbanization 10, no. 1 (April 1998): 217–32.

El Kadi, Galila. “Case Study on Metropolitan Management (Greater Cairo)”. 1992.

Fahmi, Wael, and Keith Sutton. “Greater Cairo’s Housing Crisis: Contested Spaces from Inner City Areas to New Communities.” Cities 25 (2008): 277–97.

Milbert, Isabelle. “Donor Agencies’ Urban Agenda”. 2000.

Piffero, Elena. “What Happened to Participation: Urban Development and Authoritarian Upgrading in Cairo’s Informal Neighbourhoods”. 2010.

Raymond, André. Cairo. Harvard University Press. 2000.

Serageldin, Mona. “Planning and Institutional Mechanisms” in The Expanding Metropolis: Coping with the Urban Growth of Cairo. The Aga Khan Award for Architecture, Proceedings of Seminar Nine in the Series ;Architectural Transformation in the Islamic World’, Cairo, Egypt. 1985.

Sims, David. Understanding Cairo: The Logic of a City Out of Control. American University in Cairo Press, 2012.

1.Both terms are used by the Egyptian government. The relevant government agency is called the New Urban Communities Agency (NUCA), while the website is NewCities.gov.eg

2.A full list of the World Bank’s policy notes filed under “urban development” between 2006 and 2010 can be accessed here.

3.Namely, the 1993 National Plan for the Upgrading of Scattered Settlements. The goal was to provide infrastructure and urban services for informal settlements, especially street-widening, lighting and paving (tenure was not a priority).

4.This policy has changed since the establishment of the new Ministry of Urban Development and Informal Settlements

5.The CSDV document was released in 2014, but the date printed on it is 2012.

6.For example, this document by the Japanese international development agency JICA provides an overview of its contributions to Egypt’s transport sector

Featured photo adapted from : GOPP (2009), “Cairo Future Vision 2050” Presentation.

Houssam Elokda Says:

Good Article! I think a lot of people are unaware of the initial goal of the desert cities. I wrote a recent paper about them as well, and its history gets really ugly.

Check out Doughty’s (1996) article in Aramco, it quotes one of the ex-planning officials in that time, salah el sheikh. When he was asked why their initial growth was so slow, he responded by citing the example of Brasilia, and how it took a long time for population to increase- I thought that was really funny and extremely sad at the same time.

Almost 40 years after Brasilia’s birth, after academics and planning theorists have basically torn it apart for its modernist, segregational qualities, and he cites it as an example of success!

December 15th, 2014 at 7:35 pmHoussam Elokda Says:

Also, speaking of international organizations:

http://unhabitat.org/clos-meets-egypt-pm-key-urban-development-ministers/

December 15th, 2014 at 7:36 pm