The Sustainable Development Goals: An Opportunity for Addressing Urban Inequality?

A User’s Guide to the Sustainable Development Goals

Egypt’s National Assessment of Progress Towards Sustainable Development Goals

The Preamble to the United Nations Charter, signed in 1945 at its inception, reads:

-

WE THE PEOPLES OF THE UNITED NATIONS [ARE] DETERMINED

- to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, which twice in our lifetime has brought untold sorrow to mankind, and

- to reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person, in the equal rights of men and women and of nations large and small, and

- to establish conditions under which justice and respect for the obligations arising from treaties and other sources of international law can be maintained, and

- to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom.

In San Francisco 1945, the 50 states represented at the conference –including Egypt and many Arab states- also agreed “to employ international machinery for the promotion of the economic and social advancement of all peoples.” In 2000, the United Nations –reached 189 member state by then- responded again to its foundational charter by implementing the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) to reduce extreme global poverty within 15 years. After this global partnership and attention from national governments, international institutions, and the donor community, the number of people living in extreme poverty worldwide declined by more than half—from 1.9 billion to 836 million, between 1990 and 2015. Most of the progress occurred after implementing the MDGs in 2000 (United Nations 2015). However, progress has been highly variable across and within countries. In some areas, inequalities have deepened and the poorest and most marginalized citizens have taken a step backwards (Democracy Development Programme [DDP] 2016, Sachs 2015).

A major shortcoming of the MDGs was that only national governments were positioned as the primary agents in their planning, implementation, and monitoring. Accordingly, they measured success with reference to national level indicators, with little attention paid to sub-national inequalities. By relying on aggregated figures that did not capture the inequalities and deprivations at the regional and local levels, the MDGs failed to achieve development outcomes for many segments of the population most in need (DDP 2016).

In response to these prolonged inequalities, the UN General Assembly launched a new and more comprehensive development initiative for the next fifteen years: The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). All UN member states adopted the SDGs through a non-binding international agreement and are committed to realizing the goals, or to present credible action plans for doing so at the very least. Governments around the world, Egypt included, are currently putting together such plans, which they will present at international summits such as Habitat III: The United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development in October 2016, in Quito, Ecuador.

The SDGs contain twice as many goals and five times as many targets as the preceding Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). While the MDGs and earlier development plans tried to extend education, services, and investment to rural populations, the SDGs recognize the need for more of an urban focus, as cities continue to expand and will account for over 60 percent of the world’s population by 2030 (SDSN 2013). The SDGs include a stand-alone goal: to “make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable (Goal 11).” Cities are now responsible for roughly three quarters of the world’s economic activity and as the urban population increases, so will its share of global GDP and investments (SDSN 2013). Widely recognized as the engines of growth and innovation critical to development, cities also face some of the globe’s most acute poverty, governance, service provision, and infrastructure challenges (Slack 2015). Looking ahead, improving the quality of life and sustainability in the world’s cities will be one of the most pressing global challenges of the post-2015 era.

The Sustainable Development Goals. (Source: United Nations, 2015).

The Millennium Development Goals. (Source: United Nations Development Program, 2000).

While the MDGs were directed at reducing extreme poverty, the SDGs’ first goal is to “end poverty in all its forms everywhere,” and thus goes beyond the goal of ending only extreme poverty. One billion urban dwellers residing in informal housing settlements worldwide still lack adequate basic services such as water, sanitation, drainage, solid waste collection, healthcare, and schools (Satterthwaite 2014). Despite not having access to such basic services, many informal settlement residents do not qualify as experiencing extreme poverty because they may have low wage jobs and limited incomes. In Egypt alone, approximately 16 million people live in informal settlements. Addressing the spatial inequalities and service deficits facing urban residents worldwide requires robust integration of local knowledge as well as a critical examination of political and institutional systems that perpetuate urban poverty.

While the issues that the SDGs address—human security, health, employment, climate change—are global, their solutions depend upon progress made locally (Satterthwaite 2014). Later in this brief, we will illustrate the progress that small-scale, local initiatives can make towards larger sustainable development objectives by examining a small community initiative which had limited resources to carry out garbage collection services, and was able to cooperate with local government officials and gain access to information immediately after the political opening created by the Egyptian uprising in 2011.

Access to basic services is a central theme throughout many of the SDGs. Water and sanitation (Goal 6), food security (Goal 2), investment in infrastructure (Goal 11), access to transportation (Goal 11), sustainable use of resources (Goal 12), economic growth (Goal 8)—all of these are typically delivered at the local level; in informal settlements and neighborhoods, rich and poor, legal and illegal, urban and peri-urban. As such, national governments cannot hope to achieve the goals, or to devise a credible plan for achieving the goals without considering service delivery deficits and other forms of spatial inequality that persist at the subnational and local levels. Local level actors—civil society organizations, local government representatives, and other community groups—continue to demand that their governments include them in the design and implementation of development initiatives, at a time when the international community is publicly and institutionally committed to realizing the SDGs. Local actors often understand that they may need technical expertise and financial resources to realize the SDGs, but their efforts are also embedded within a particular political and economic structure, which they must negotiate as well.

The importance of “localizing” the SDGs has been central to many high-level dialogues about the Post-2015 Agenda. National governments alone most likely do not have the resources, the bureaucratic edifice, or the political will to fulfill all of the SDG goals. Local district and provincial leaders may understand the scope of urban problems and have the capacity to solve some of those problems if they work in league or have the political approval of national actors to act, even though many local government structures are poorly resourced. As a group of UN agencies said in 2014 when initiating a series of local and national consultations on the role of local level actors in implementing the SDGs, “Most critical objectives and challenges of the Post-2015 Development Agenda will certainly depend on local action, community buy-in and local leadership, well-coordinated at and with all levels of governance… Accountable local governments can promote strong local partnerships with all local stakeholders—civil society, private sector, etc. Integrated and inclusive development planning that involves all stakeholders is a key instrument to promoting ownership and the integration of the three dimensions of development—social, economic, and environment” (UNDG 2014, 6). While such dialogues are useful for promoting cooperation between local government, civil society, and the private sector, they do not tell us much about how to realize these roles, or what to do when political realities, contestation, or financial issues make them impossible. Realizing the SDG goals with the cooperation and contributions of NGOs and civil society at the local scale may be very difficult when, for example, central or subnational governments are ineffective, under-resourced, authoritarian, repressed, or corrupt.

The Middle East has some of the least democratic local government institutions in the world, since many local and regional office-holders are appointed by the central government and fiscal control is heavily centralized.1 Egypt, in particular, has not held local elections since 2010 after elected Local Popular Councils were disbanded in June 2011, after the fall of the Mubarak government (TADAMUN 2016). Furthermore, the relationship between the state, local government, and civil society in much of the region is often contentious. Indeed, political leaders and government officials in much of the world are more interested in staying in power than in producing effective, inclusive, and sustainable development outcomes that address the needs of marginalized and neglected populations living within their countries (Boex 2015). That said, even in contexts where local government is ineffective or undemocratic, or where the capacity of civil society is repressed, ordinary citizens and community groups can and do take action to improve their neighborhoods and cities, often with significant success. While such small-scale efforts can have a very real impact on progress towards SDGs, conversations about these goals should also consider political realities that may impede their achievement. The SDGs in turn, as internationally sanctioned development priorities, may offer a powerful platform and new opportunities for civil society and other collective actors to pressure their governments to take action.

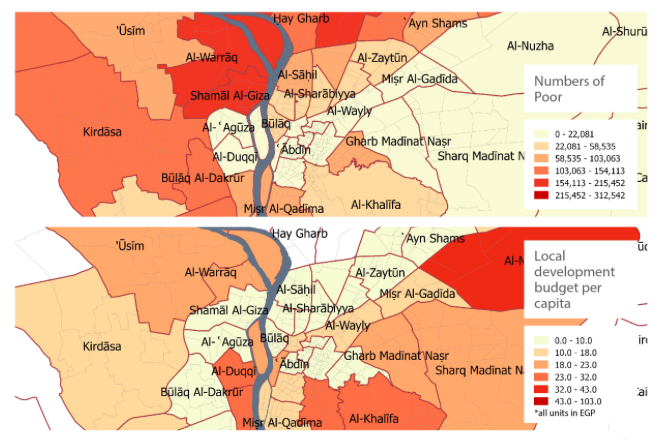

In Egypt, TADAMUN has been working to understand spatial inequality in Cairo, since most studies on the subject do not move beyond a crude urban/rural dichotomy or a provincial level of analysis. Although income inequality in Egypt is considered to be fairly low by global standards, largely because poverty extends equally across many rural areas, in large urban areas (where the very wealthy live) inequality is higher than in rural areas. In fact, the level of inequality in Cairo is higher than in any other governorate in the country, followed by Alexandria (Milanovic 2014, 54).2 The bulk of public expenditure in Egypt is managed at the governorate level. Central ministries distribute budgets to their directorates in the different governorates and there is no way to see how directorate resources are then distributed at the local level. In practice, the distribution of public resources often depends more on political bargaining and negotiation between government officials and bureaucratic entities than poverty indicators, needs, or deprivation. A very small proportion of public expenditure is managed on the district level, and without examination of local level needs, planning and budget allocation cannot reflect the actual service provision and other development deficits at the community level, making the distribution of public resources highly unjust. Moreover, without transparent decision-making and available information on local level needs and inequalities, there is no way to hold government accountable to target public resources appropriately. If public investment cannot be targeted to areas most in need of services, infrastructure, or job opportunities, because they ignore data analysis at the neighborhood level, areas with the most deprivation will be unable to climb out of poverty.

For example, the following maps illustrate a clear mismatch between the poorest districts in the Greater Cairo Region and the government’s allocation of local development projects and funds. While there are also other development and social welfare public goods outside of local development funds (graphed here), we can see using publicly available data that some of the wealthiest districts in Cairo, such as al-Nuzha and Dokki, receive far more support than the poorest areas of the city.

The number of people below the poverty level (top map) compared to the local development budget per capita (bottom map) in the Greater Cairo Region. (Source: TADAMUN: The Cairo Urban Solidarity Initiative, 2015).

The debate about spatial inequality in Cairo or the unjust distribution of local development funds raises a key dimension of the SDGs because the new UN agenda emphasizes the roles that local actors can and do play in the design, implementation, and evaluation of development initiatives to improve their cities and neighborhoods. It advocates broader inclusion of local stakeholders in all development processes and addresses some ways in which “localization” of the goals has the potential to avoid some of the shortcomings of previous global development goals. Yet, we also cannot forget some of the institutional and political constraints on local actors participating in development planning and initiatives since civil society has to have some legal and official standing, if not support, to play an active role in meeting the SDGs.

A case study of a community driven solid waste management project in Nahia, Egypt, illustrates the progress that small-scale, local initiatives can make towards larger sustainable development objectives, despite some constraints. TADAMUN has documented and researched this case and others like it to underscore the capabilities of local initiatives and community groups to address challenging problems and improve their communities, while using limited resources and managing to cooperate with government officials or other institutions. After the 2011 uprising in Egypt, ‘initiatives’ multiplied as a wide array of community groups, including many young people, began focusing on the imbalance and inadequacies of public services.

Case Study: The Nahia Garbage Project

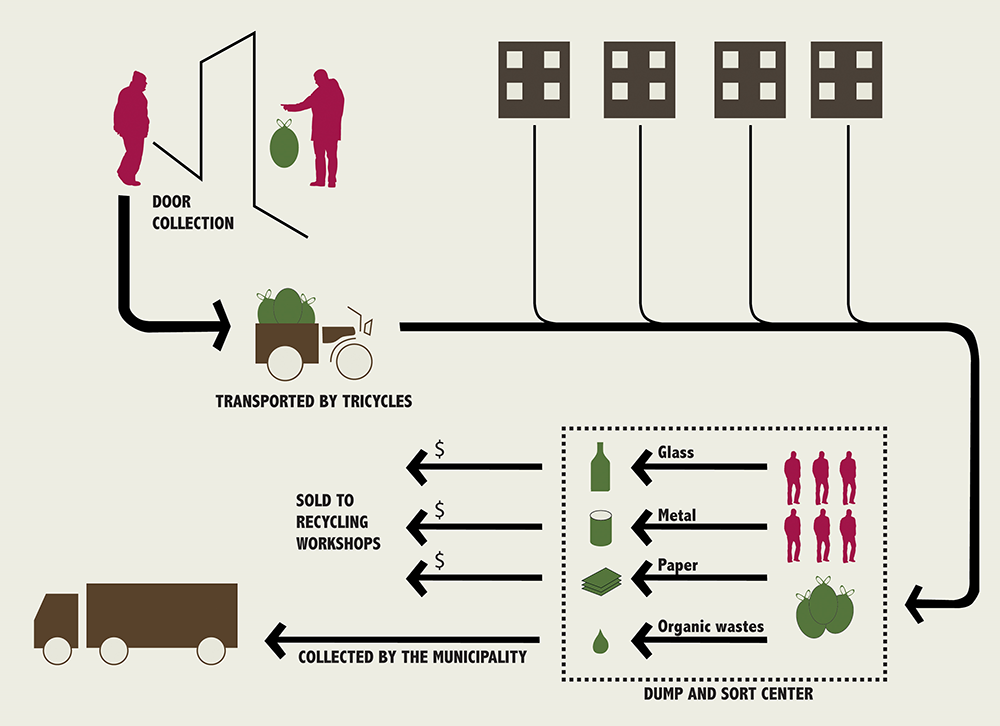

Despite the daunting challenges facing civil society and limitations of local government, community initiatives all over Egypt are testament to the capacity of civil society organizations to design and implement innovative solutions to their communities’ most pressing development needs. The efforts of the “Nahda Foundation,” a citizen-led community organization, to provide solid waste management services to the residents of Nahia is one such example. Nahia is a village of approximately 44,000 residents located in the Kirdāsa district of Giza governorate along the western perimeter of Greater Cairo (TADAMUN 2013a).3 Its residents suffered from polluted drinking water, resulting in high rates of kidney disease and water unsuitable for agricultural irrigation (TADAMUN 2013a). Due to the absence of an effective solid waste collection and management system since the area was defined as rural and thus did not have access to the Giza City sanitation system, garbage piled up in the streets, waterways were used as dumping sites for garbage and sewage seeped into the drinking water supply (TADAMUN 2013a). In January 2012 a group of Nahia residents formed a community organization, the “Nahda Foundation,” and launched the “Nahia Garbage Project” to address the village’s solid waste and public health problems. 4

The community members behind the initiative utilized their acute neighborhood knowledge to identify one of the community’s most exigent development demands and designed a locally-tailored solution, which took into account Nahia’s unique capacities and constraints. The Nahda Foundation developed a plan for collecting and disposing of garbage that was feasible and effective and did not require significant resources or major government or infrastructural intervention.

The project operated on a subscription basis. Individual homes subscribed to the service and paid a monthly fee (10 – 15 EGP, depending on the size of the building) directly to the workers who collected garbage (TADAMUN 2013a). In addition, the project collected garbage from several public and government buildings at no charge, including schools and the local hospital. Workers then transported the garbage to the dump site, where it was sorted and recyclable materials were sold to raise additional revenue (TADAMUN 2013a). The project’s initial costs for equipment, workers, and outfitting the dumping site totaled roughly 185,000 EGP, which the Foundation raised through zero-interest personal loans and in-kind donations (TADAMUN 2013a).5 Two charitable organizations donated the motorized tricycles to be used for garbage collection and following negotiations and some pressure the Foundation was able to use a plot of government land for the dumping site (TADAMUN 2013a).

Nahia Village Solid Waste Management System. (Source: TADAMUN: The Cairo Urban Solidarity Initiative, 2015).

After a few years, the project was financially self-sustaining, raising enough in subscriptions and selling recyclable materials to cover costs and to pay back initial loans (TADAMUN 2013a). Moreover, the project provided employment for 23 workers (TADAMUN 2013a). The Nahda Foundation reported that 70% of the entire village benefitted from the project and TADAMUN observed a marked improvement in the cleanliness of the streets compared to images and videos from 2010 (TADAMUN 2013a). The fact that the project was self-financing is particularly important, as development agencies and donors seem to be scaling back official development assistance and transferring financial and managerial responsibilities of development programs to partner governments (Boex 2015). In this context of declining bilateral or multilateral development assistance, it is increasingly important that development initiatives are financially sustainable.

The success of the Nahia Garbage Project is testament to the fact that small-scale community efforts making use of existing local capacities, resources, and structures have the ability to make meaningful and measurable progress towards addressing pressing development deficits and achieving SDGs. Modest, inexpensive, and technologically unadorned, the Nahia Garbage Project advanced several SDGs and drastically improved a major development deficit that threatened the health and well-being of the people living there. For example, the project provided Nahia’s residents with a new, effective and affordable trash collection service, which they had lacked previously (Target 1.4: universal access to basic services). Also, by relieving the solid waste buildup in the city’s streets and water systems, the initiative targeted a chief source of water supply contamination and a grave risk to public health (Goal 6: clean water and sanitation; Target 6.8: support and strengthen the participation of local communities in improving water and sanitation management; Target 3.9: reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water, and soil pollution and contamination). Furthermore, the project created many jobs for workers (Goal 8: decent work and economic growth), and by sorting and recycling refuse, instituted more sustainable trash disposal methods (Target 12.5: substantially reduce waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling, and reuse). More generally, the project made Nahia a cleaner and safer place to live (Goal 11: make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable).

Local Level Development: Central to the SDGs

Targeting Those Most in Need: The Role of Local Government and Civil Society

The full and meaningful participation of local actors in development planning, implementation, and evaluation is absolutely required for SDGs to make progress towards reducing the spatial inequalities and development deficits impacting the world’s cities. Local governments and civil society organizations can be critical actors when it comes to amplifying the voices of marginalized and underserved communities whose needs have been overlooked by national and global development efforts. Excluded communities, such as the urban poor residing in informal settlements across the globe and young people, tend to lack the capability and resources to raise their demands to the forefront of national development agendas (Satterthwaite 2014, DDP 2016).

Likewise, top-down national development agendas are often too broad to take into account the unique needs and priorities of every local community residing within their borders.

As the level of government closest to the people, local governments are often better suited than their national counterparts to engage marginalized communities within their jurisdictions, to listen to, understand, and respond to their specific needs, desires, and interests (Slack 2015). In many cases, “local governments are often legitimate and sustainable local actors; they are intimately familiar with the local context, their raison d’être is to promote the well-being of their constituents and the development of their local jurisdiction, and their overhead costs are already paid for” (Boex 2015, 5). But what happens when they are not? How can local governments address the needs of underserved communities if they lack political, administrative, or financial power? And even if they do possess these capabilities, how do we know they will act in the interest of citizens most in need?

In Egypt, for example, the local administration currently receives over 90% of their budget directly from the central government and must navigate a complex set of bureaucratic procedures and approvals from various government ministries to carry out even the most basic activities (TADAMUN 2016).6 Local Popular Councils, the only democratically elected local government bodies, are charged with undertaking the comprehensive development of local communities, but must submit their decisions to the Governor (appointed by the central government) for approval (TADAMUN 2016). The Ministry of Local Development has complete oversight powers over subnational units (cities, districts, villages, markaz [a kind of provincial city or larger village], and neighborhoods or shiyakhas), from budget scheduling to monitoring individual local officials’ job performance (TADAMUN 2016).7 This institutional arrangement favors executive power interference in local decision-making and renders it exceedingly difficult for local administration to adequately provide basic services to citizens, or to tailor public service policies to better meet local needs, for example. It also makes district officials, in many instances, more accountable to the central government than to their own constituents. Local government officials, if they are dependent upon national ministries and agencies for their operating budget, policy approvals, and professional future, will inevitably act according to the will and interest of those national ministries and agencies rather than that of the people they are meant to serve. Simply because they are closer to the people does not mean that local governments are inherently and selflessly motivated to realize sustainable development outcomes (Boex 2015). Like their national counterparts, local government officials face a variety of incentives, competing interests, and policy demands. They are political actors with their own self-interested agendas susceptible to elite capture (Boex 2015).

Civil society organizations (CSOs), particularly in areas where local government is weak or unrepresentative, still sponsor initiatives to meet the needs of marginalized and underserved communities, in line with many of the SDGs. Because of their proximity to local communities, CSOs are well situated to identify development deficits in the areas in which they operate and work with their communities to remedy them. They often possess the knowledge and exposure to develop disaggregated local-level data, to devise more pointed definitions of benchmarks and indicators by which to measure success, and to monitor development local development initiatives and the various dimensions of their impact on citizens. CSOs and community federations of informal settlement residents, for example, have developed detailed surveys, censuses, and maps of informal areas, capable of capturing a more accurate picture of local development needs (Satterthwaite 2014). It is not clear, however, how CSOs will fit into the broader SDG goals. Will they be given a voice in informing broader national development plans? Will the SDG agenda be imposed on CSOs, which have little choice but to align their work with the agendas of donor organizations or official development assistance? Furthermore, can CSO initiatives really scale up? Do they have the financial and administrative resources to provide public services to a broader population or is that the national government’s responsibility? Should social welfare provision be project-based and limited to particular communities or groups or is the right to adequate housing, clean water, sanitation, or a decent education, a fundamental right for all citizens to share, despite where they might live? And perhaps most importantly, what role can CSOs play when government repression severely limits their ability to act?

The political terrain that Egyptian CSOs and NGOs must navigate severely limits their freedom to operate and to contribute to a more successful SDG process. Egypt has a long history of contentious civil society-state interaction, which has unfortunately endured in the post-Mubarak era. Today NGOs and other civil society groups in Egypt are subject to harassment and severe restrictions to comply with the 2002 Law on Associations, despite government pledges to replace the old law with a new one up to international standards (Human Rights Watch 2016, Mada Masr 2016). Most recently, Egyptian authorities have forcibly closed several NGOs and pursued increasingly restrictive measures against NGO employees, including detention, prosecution, travel bans, and freezing the assets of organizations (Mada Masr 2016).

Conclusion

The SDGs and the conversation surrounding them have addressed what needs to be done to achieve the 17 goals, but not how or by whom. Although the goals include recommendations to “ensure responsive, inclusive, participatory, and representative decision-making at all levels” (Goal 16.7), they focus on national government plans and largely ignore the role of local government and civil society (including opposition forces)—two of the most important urban actors (Satterthwaite 2014). Like the MDGs, the SDGs are a voluntary agreement rather than a binding treaty: “We recognize that each country has primary responsibility for its own economic and social development” (UN 2015, “Transforming Our World,” Preamble). According to the UN, it is the responsibility of individual member states to develop their own national sustainable development plans. But the document stops short of suggesting any effective accountability mechanism that would compel national governments to include local actors in the planning, implementation, or monitoring process. It is therefore crucial for national governments to facilitate participation of local government and all sectors of society in the planning and implementation of the goals, and it is the responsibility of local government, civil society, and the general public at the local level to hold governments accountable, so that the SDGs will benefit all citizens, particularly those most in need.

Even in contexts where institutional, political, or capacity constraints limit the scope of possibility for broader participation in local or national government development initiatives, local actors are still able to make very real progress towards SDG objectives. Community initiatives like the Nahia Garbage Project illustrate the innovative and organizational capability of ordinary citizens to mobilize and improve the areas in which they live and the lives of others living in their communities. A proper pursuit of the SDGs must highlight the importance of small-scale projects such as this one for its effectiveness in addressing inequalities and for devising creative demand-driven solutions to their communities’ most pressing development needs.

At the very least, the SDGs provide an opportunity for advocates to pressure their governments to include local stakeholders and local knowledge in the design and implementation of development initiatives, and to place sub-national inequalities at the center of their development priorities. The SDGs also bring into being a powerful lexicon upon which civil society actors can draw to raise support for their initiatives, if they have the right to organize, the right to information, legal standing, and autonomy. Those drafting and negotiating the SDGs recognize that “[c]ities are where the battle for sustainable development will be won or lost and local government institutions and local community groups and leaders must be part of that effort” (United Nations 2013).

Works Cited

Bhamra, Anshul S., Kriti Nagrath and Zeenat Niazi. 2015. “Role of Non-State Actors in Monitoring and Review for Effective Implementation of the Post-2015 Agenda.” Independent Research Forum, Background Paper 4, May.

Bissio, Roberto. 2015. “The “A” Word: Monitoring the SDGs.” Future United Nations Development System, Briefing 26: February.

Democracy Development Programme. 2016. “The Roles of Civil Society in Localising the Sustainable Development Goals.” Prepared for the African Civil Society Circle. March.

Harb, Mona and Sami Atallah, eds. 2015. Local Governments and Public Goods: Assessing Decentralization in the Arab World. The Lebanese Center for Policy Studies, Beirut, Lebanon.

Mada Masr. 2016. “UN experts raise alarm at Egypt’s NGO crackdown.” 11 April.

Milanovic, Branko. 2014. “Spatial Inequality.” In P. Verme, B. Milanovic, S. Al-Shawarby, S. El Tawila, M. Gadallah & E.A.A. El-Majeed (Eds.), Inside Inequality in the Arab Republic of Egypt.: Facts and Perceptions Across People, Time and Space, pp. 37-54. World Bank, Washington, D.C.

Pogge, Thomas and Mitu Sengupta. 2015. “The Sustainable Development Goals: A Plan for Building a Better World?” Journal of Global Ethics, Vol. 11, Issue 1, 13 March.

Sachs, Jeffrey D. 2012. “From Millennium Development Goals to Sustainable Development Goals.” The Lancet. Vol. 379. Pp. 2206-2211. June 9 – 15.

Satterthwaite, David. 2014. “Guiding the Goals: Empowering Local Actors.” SAIS Review of International Affairs, Vol. 32, No. 2, Summer-Fall 2014.

Slack, Lucy. 2015. “The Post-2015 Global Agenda: A Role for Local Government,” Commonwealth Journal of Local Governance, 16/17: June.

Sustainable Development Solutions Network. 2013. “Why the World Needs an Urban Sustainable Development Goal.” Sustainabledevelopment.un.org. September 18.

TADAMUN. 2016. “Proposed Local Administration Law Strengthens the Powers of Central Government and the Governorates Instead of Local Administrations and Elected Councils.” 15 January, Cairo, Egypt.

TADAMUN. 2013 (a). “Nahia Village Solid Waste Management.” The Cairo Urban Solidarity Initiative, 23 June, Cairo, Egypt.

TADAMUN. 2013 (b). “Why Did the Revolution Stop at the Municipal Level? Local ‘Administration’ and Centralization in Urban Egypt.” The Cairo Urban Solidarity Initiative, 23 June, Cairo, Egypt.

United Cities and Local Governments. 2015. “The Sustainable Development Goals: What Local Governments Need to Know.” September 2015.

United Nations. 2013. “New Global Partnership: Eradicate Poverty and Transform Economies Through Sustainable Development.” High Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda. 17 May.

United Nations. 2015. “The Millennium Development Goals Report 2014.” UN.org. Retrieved 2 April, 2016.

United Nations. 2015. “Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.” Sustainabledevelopment.un.org. Retrieved 2 April, 2016.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). N.d. “Local and Regional Governments at the Heart of the Global Agenda.” Sustainabledevelopment.un.org. Retrieved 2 April, 2016.

United Nations Development Group (UNDG). 2014. “Localizing the Post-2015 Development Agenda: Dialogues on Implementation.” United Cities and Local Governments.org. Retrieved 2 April, 2016.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) 2015. “World Leaders Adopt Sustainable Development Goals.” 25 September 25. Retrieved

1.See Harb and Atallah (2015) on decentralization in the Arab World.

2. The rural gini coefficient was 37.5, while the urban gini coefficient was 26.5 in the 2005 Household Expenditure and Income Survey (HEICS), (Milanovic 2014, Table 2.2, p. 41). Cairo is the most unequal of all governorates with a Gini of 40.5, followed by Alexandria with a Gini of 38.5 (Milanovic 2014, 54). The Gini coefficient is one of the most commonly used indicators to measure inequality by measuring the distribution of income among the population. The values range between 0 and 1 (can also be represented as a 0-100%), with a 0 value meaning equal distribution of income, and a value of 1 meaning that all of the income generated is held by 1 person.

3. The 44,000 figure is taken from CAPMAS data from the 2006 census. Residents estimate that the population has reached approximately 100,000 since that time.

4.The Nahda Foundation initiated the Nahia Garbage Project in the period following the 2011 revolution, amidst the formation of Popular Committees and an eagerness on the part of citizens to participate in popular projects to improve their communities.

5. The price of the land for the dump site is not included in this figure, as this was an in-kind concession by the government to the Foundation. After securing the land, the Foundation assumed the cost of constructing a perimeter around the site.

6. “By definition, Egypt does not have local government, but instead local administration—a matter of semantics with wide-ranging implications. To understand this point is crucial to understanding the challenges facing communities in Egypt’s cities.” The Ministry of Local Development, not government, supervises the subnational level. See TADAMUN (2013b).

7. Egypt is divided into governorates, provinces, cities, districts, and villages for administration purposes and the levels of administration differ by governorates. There are currently 27 governorates in Egypt (muhaaftha). As of 2002, there were 166 “centers” (markiz/marakiz) and 200 metropolitan areas that are designated as cities. Each city is further subdivided into districts, (ahiyaa’) of which there are hundreds. Cairo alone had 23 districts (one estimate put this number at 34), which does not include Giza, which, while part of the Greater Cairo Area, is its own governorate with many rural villages (qura) and cities (madina) attached to it. A Markiz is a higher level of administration over cities and villages, largely found in more rural provinces. See TADAMUN (2013 b).

Featured Photo By Chehab Adel, shared with public on facebook.

Collage photo By TADAMUN: The Cairo Urban Solidarity Initiative

Comments