The Right to a Sustainable Environment

The right to a sustainable environment is the right of everyone today and in future generations to enjoy a safe and clean environment. It is the right for all people to breathe clean air, drink safe water, enjoy neighborhoods free from sewage and garbage, and to walk safely on the streets. It means protecting the environment from noise nuisance, air pollution, pollution of surface waters, and the dumping of toxic substances. The right to a sustainable environment is also an obligation. Just as the city belongs to all residents, so does the environment, therefore it is the collective responsibility of state, non-state, and individual actors to protect it.

The right to a sustainable environment was first put on the international agenda in the 1972 Stockholm Declaration on the Human Environment. It states that:

Man has the fundamental right to freedom, equality and adequate conditions of life, in an environment of a quality that permits a life of dignity and well-being, and he bears a solemn responsibility to protect and improve the environment for present and future generations. In this respect, policies promoting or perpetuating apartheid, racial segregation, discrimination, colonial and other forms of oppression and foreign domination stand condemned and must be eliminated.

In 1992, the UN Conference on Environment and Development (known as the Earth Summit) in Rio de Janeiro, called on governments to rethink economic development and find a way to stop the irresponsible destruction of natural resources. Delegates from 178 countries (Egypt among them) signed the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development which states: “In order to achieve sustainable development, environmental protection shall constitute an integral part of the development process and cannot be considered in isolation from it.” While provisions about the right to a sustainable environment are the core content of these international summits and conferences, they are also implicit in most human rights conventions. For example, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights both guarantee the right to an adequate standard of living, the right to housing, the right to integrity, and the right to equality. Without a safe and healthy environment in which to live, work, play, and socialize, none of these can be realized.

Pollution in Cairo is threatening the health and wellness of Cairenes, diminishing the quality of life, and limiting the city’s inherent potential. Air pollution is perhaps Cairo’s most pressing and intractable environmental problem, but Cairo is also beleaguered by a mounting garbage problem, and poor water and sanitation facilities in some neighborhoods. While we all enjoy having clean streets, drinking pure water, and not worrying about our waste, public services are not always fairly distributed. Citizens of al-But and Isa in Damiatta do not enjoy the same level of safe water as the citizens of Garden City and Zamalek in the Greater Cairo area. Even clean air is not fairly distributed as many of the lower-income settlements are located near industrial areas.

Cairo has some of the worst air pollution in the in the world (Leitzell 2011). A World Health Organization study showed that spending a day breathing the air in Cairo is the equivalent of smoking a pack of cigarettes (Khaled 2013). While Cairo is the undisputed economic capital of Egypt, the environment has suffered because of it. Egypt has approximately four million vehicles, half of which are in Cairo. There are thousands of factories in and around Cairo that spew toxic chemicals into the air, raising the incidence of asthma and other respiratory diseases (Abdel-Halim et al. 2003). An infamous black cloud descends on Cairo each year after the hottest days of summer when farmers, hundreds of miles away, burn their agricultural waste. Cairo’s topography and dry climate make the situation even worse. Strong winds carry pollution from hundreds of miles away to settle in the river valley and because it barely rains in Cairo, there is no natural cleansing (Leitzell 2011).

Waste disposal is another major environmental challenge for Cairo. The citizens of Cairo produce 17,000 tons of trash per day. About 8,000 tons of trash are collected by zabbaleen and 3,000 tons are collected by private waste disposal companies, but the remaining 6,000 tons are left on the streets, dumped in abandoned canals or sometimes into the Nile (El Deeb 2012). Many settlements in Cairo, especially in the peri-urban areas, are without adequate sanitation facilities leading to the spread of diseases like schistosomiasis (Hopkins and Mehanna 2003) and a high incidence of diarrhea. Hundreds of factories discharge their industrial waste directly into the Nile River untreated and agricultural run-off from farms along the Nile also threaten the quality of water in Cairo (“The Solution to Pollution” 2012). Further compounding this problem is the fact the Nile is the only major source of water in the country. If Egyptians fail to protect the Nile, what recourse will they have for the future?

Environment in the Egyptian Law

The now-defunct 2012 Constitution addressed the right to sustainable environment in Article 63: “All individuals have the right to a healthy environment. The State shall safeguard the environment against pollution, and promote the use of natural resources in a manner that prevents damage to the environment and preserves the rights of future generations.”

The Constitution also addressed environmental rights implicitly in other Articles, including Article 15 which designates state responsibility to protect and increase farmlands. In Article 18 the state assumes responsibility to protect natural resources; Article 19 declares the Nile River and other water resources as national wealth and obliges the state to protect them; and Article 20 obliges the state to protect its coasts, seas, waterways, and lakes.

In addition to the Egyptian Constitution, Law Number 4 of 1994 is the main source of reference for environmental regulations, management, and planning in Egypt. Law Number 4 of 1994 for Promulgating the Environment Law restructured the Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency (EEAA) with new and broader responsibilities to replace the environmental institution initially established in 1982. According to this law, EEAA represents the executive arm of the Ministry of Environmental Affairs. [1] Since this law, EEAA has become the national authority for formulating national and local environmental policies, preparing and implementing environmental projects, and promoting environmental relationships with other countries.

In addition to the Egyptian Constitution, Law Number 4 of 1994 is the main source of reference for environmental regulations, management, and planning in Egypt. Law Number 4 of 1994 for Promulgating the Environment Law restructured the Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency (EEAA) with new and broader responsibilities to replace the environmental institution initially established in 1982. According to this law, EEAA represents the executive arm of the Ministry of Environmental Affairs. [1] Since this law, EEAA has become the national authority for formulating national and local environmental policies, preparing and implementing environmental projects, and promoting environmental relationships with other countries.

Decentralization, Citizen Engagement, and the Structure of Environmental Management

The 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg emphasized the importance of promoting citizen engagement in the environmental decision-making process, including providing access to information regarding laws and regulations as well as policies and programs related to environmental issues. As a participant state in the 2002 Johannesburg Summit, Egypt took certain steps to improve citizen engagement and public access to information. A major step by the EEAA was to decentralize the structure of environmental management.

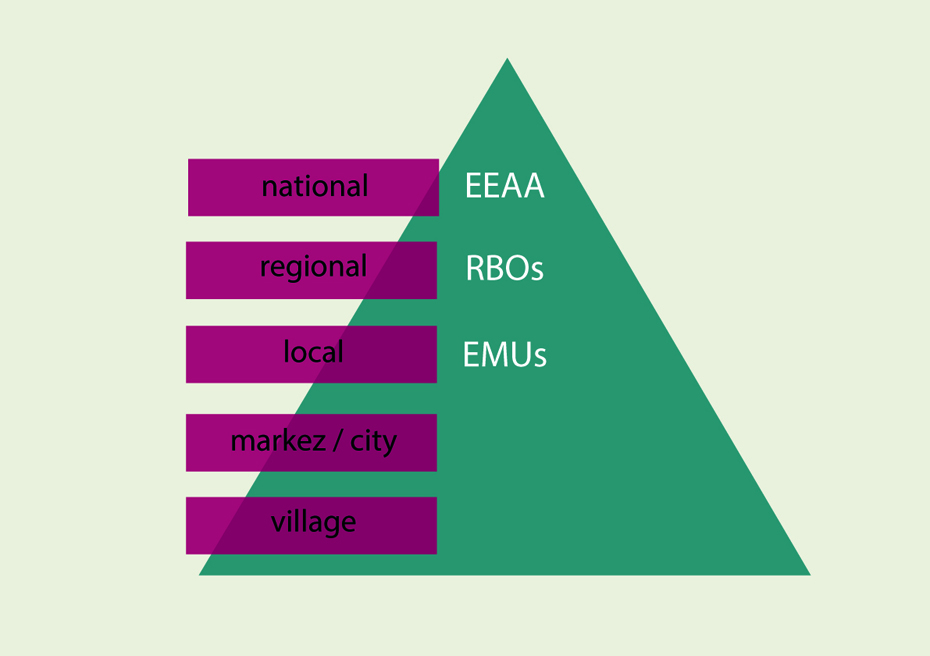

Law Number 4 of 1994 allows the Ministry of Environmental Affairs to establish Regional Branch Offices of the EEAA (RBOs). Ministerial Decree No. 187 of 1995 established eight RBOs, each responsible for a few governorates around the country. In June 2003, the Ministry established Environmental Management Units (EMUs) as the local authority at the governorate level to develop, implement, and supervise local environmental plans and projects in cities and villages. The EMUs and the Governorate Environmental Action Plan Unit (GEAP) work directly with the governorates in planning and implementing local environmental plans.

The Structure of Environmental Management in Egypt. Source: The Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency (EEAA)

The local institutions, EMUs and GEAP, have the authority to develop environmental plans, implement those plans, and supervise them. For resource allocation, however, they still depend on the EEAA as it is the national authority. The EEAA and the Ministry of Environmental Affairs review the proposed local-level environmental projects and decide where to allocate the available resources and funds. They then coordinate with responsible central government institutions (such as the Ministry of Health and Population) as well as international donors (like USAID) to allocate their resources to the selected local projects. These projects are then executed by the local administrations which are accountable to the EEAA.

The decentralization of the environmental management structure, however, was not accompanied by strong steps to promote citizen engagement in the process of environmental decision making. Unfortunately, the EEAA pays more heed to the Egyptian and international experts rather than to grass roots actors and their mobilization (Hopkins and Mehanna 2003).

Where to Begin

The right to a sustainable environment requires close cooperation among local residents and NGOs, local and central governmental agencies, as well as regional and international donors and agencies. The Ministry of Environmental Affairs has taken many steps to improve the quality of the environment. They replaced thousands of old taxis and other ageing vehicles with new ones to reduce the level of air pollution in Cairo, they are building the Gabal El-Asfar Wastewater Treatment Plant (GAWWTP) to serve the middle and lower parts of Cairo east, and they have been working closely with international organizations such as the United National Environmental Program to develop sustainability plans.

However, the pressures on Cairo’s environment will only continue to grow. The number of cars in Cairo will increase, the capacity of the factories will increase as people demand more materials and look for more work, the garbage production in the city will grow, and more people will need more water and sanitation services. Sustainability actions can be temporarily effective and more sustainable plans need structural changes. The decentralization of environmental policy-making is a start, but it also demands active citizen engagement at all levels of plan formulation, implementation, and supervision.

Despite its crucial significance to our lives, unfortunately, environmental sustainability is not in the post-revolutionary political agenda. While the Egyptian political arena witnesses fierce debates over every single issue, the right to a sustainable environment is barely heard in those debates. Raising public awareness of environmental problems should be added to the post-revolutionary political agenda. Gradually an environmental movement is growing in Egypt yet residents in the hardest hit areas of the city need to be included and involved in the movement to strategize about improving the environment in urban Egypt and the nation as a whole. Grassroots pressure on politicians and alliances with civil society, educational institutions, scientists, and activists is urgently needed to address Egypt’s current and future environmental challenges.

[1] The first full-time Egyptian Minister of Environmental Affairs took office in 1997.

Work Cited:

Abdel-Halim, A. S., E. Metwally and M.M. El-Dessouky. 2003. “Environmental pollution study around a large industrial area near Cairo, Egypt.” Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry, 257(1): 123-124.

El Deeb, Sarah. 2012. “Egypt’s Garbage Problem Continues to Grow.” Huffington Post. September 1, 2012. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/09/01/egypt-garbage-problem_n_1849254.html

Khaled, Rana. 2013. “Air pollution indoors and outdoors high, threaten health and environment.” Egypt Independent. 21 April, 21, 2013. http://www.egyptindependent.com/news/air-pollution-indoors-and-outdoors-high-threaten-health-and-environment.

Hassanein, Saleh. (n.d.). “Air Pollution in Cairo: The Cost.” Arab World Books. http://www.arabworldbooks.com/articles1.html

Hopkins, Nicholas S. and Sohair R. Mehanna. 2003. “Living with Pollution in Egypt.” The Environmentalist, 23: 17-28.

Ismail, Abdel-Mawla. 2008. “Drinking Water Protests in Egypt and the Role of Civil Society.” In Reclaiming Public Water: Achievements, Struggles and Visions from Around the World, edited by Belén Balanyá, Brid Brennan, Olivier Hoedeman, Satoko Kishimoto and Philipp Terhorst. Transnational Institute and Corporate Europe Observatory

Leitzell, Katherine. 2011. “A black cloud over Cairo.” Earth Observatory System Data and Information System, NASA. September 22, 2011. http://earthdata.nasa.gov/featured-stories/featured-research/black-cloud-over-cairo.

“The Solution to Pollution.” 2012. American University of Cairo. Accessed July 14, 2013. http://www.aucegypt.edu/newsatauc/Pages/story.aspx?eid=934

Wingqvist, Gunilla Ölund, Ben Smitth and Holger Hoff. 2010. “A Concept Note on Water in the MENA-region.” The Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida). https://www.vub.be/klimostoolkit/sites/default/files/documents/a-concept-note-on-water-in-the-mena-region.pdf

Comments