The Right to Adequate Housing in the Egyptian Constitution

What is the difference between “housing” and “adequate housing”? How does it relate to citizens living in peace and dignity in a healthy environment? Who is responsible for providing housing for citizens? And what is the role of the government? This article tries to address these questions in light of recent changes in the Egyptian Constitution.

What is the Right to Adequate Housing?

In 1966, the United Nations released the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which recognized “the right of everyone to an adequate standard of living for himself and his family, including adequate food, clothing and housing, and to the continuous improvement of living conditions” (Article 11). Signatories to the Covenant pledged to undertake necessary steps to realize this right.

However with different actions taken by governments towards fulfilling this right, it became evident that a clear definition of what constitutes “adequate housing” was needed. In 1991, the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights acknowledged that adequate housing is more than four walls and a roof; that it is the right to live somewhere in security, peace, and dignity. For housing to be adequate, it should, at a minimum, meet the following criteria:1

Legal security of tenure: Tenure takes a variety of forms, including rental (public and private) accommodation, cooperative housing, lease, owner-occupation, emergency housing, and informal settlements (including occupation of land or property). Notwithstanding the type of tenure, all persons should possess a degree of security of tenure, which guarantees legal protection against forced eviction, harassment, and other threats.

Availability of services, facilities, and infrastructure: An adequate house must contain certain facilities essential for health, security, comfort, and nutrition. All beneficiaries of the right to adequate housing should have access to natural and common resources, safe drinking water, energy for cooking, heating and lighting, sanitation and washing facilities, means of food storage, waste disposal, site drainage, telecommunication, and emergency services.

Affordability: Personal or household financial costs associated with housing should be at such a level that the attainment and satisfaction of other basic needs are not threatened or compromised. The percentage of housing-related costs should, in general, be proportionate to income levels, through housing subsidies and finance mechanisms. Tenants should also be protected against unreasonable rent levels or rent increases.

Habitability: Adequate housing must be livable and provide adequate space for its inhabitants. It should also be structurally intact and provide protection from cold, dampness, heat, rain, wind or other threats to health.

Accessibility: Disadvantaged and marginalized groups must be accorded full access to adequate housing resources. Thus, groups such as the elderly, children, the physically and mentally challenged, the terminally ill, victims of natural disasters, people living in disaster-prone areas and other groups should be given priority consideration in the housing sphere.

Location: Adequate housing must be in a location that allows access to employment options, health-care services, schools, child-care centers, and other social facilities. This is true both in large cities and in rural areas where the temporal and financial costs of getting to and from the place of work can place excessive demands upon the budgets of poor households. Similarly, housing should not be built on polluted sites or near pollution sources that can threaten the health of the inhabitants.

Cultural adequacy: The way housing is constructed, the building materials used and the policies in place must appropriately enable the expression of cultural identity and diversity of housing. Housing initiatives, either public or private, should ensure that the cultural dimensions of housing are not sacrificed and that facilities are technologically appropriate and adequate.

The right to adequate housing is guaranteed for all people regardless of their income level, financial resources, or socioeconomic background. It encompasses everyone who lives in the country and under its sovereignty, citizens, foreigners, and refugees.

What is the Impact of the Right to Adequate Housing on our Everyday Life?

Egyptians have been suffering from a chronic housing crisis for the past several decades, but how did we reach this point? And is it the state’s obligation to directly provide housing to all citizens?

It is unfeasible for the government – any government – to directly supply the housing needs of all of its citizens. In Egypt, the government directly provides only 10-15% of the national housing needs through its different housing programs. As such, the government needs to focus its efforts in these programs on ensuring that the most vulnerable members of society are given priority in the allocation of housing units and protecting them against forced eviction and guaranteeing a minimum quality standard for housing. This is a good place to start from, but more is needed to comprehensively address the right to adequate housing in Egypt. The government needs to address other housing-related issues that affect the supply and quality of housing in Egyptian cities.

Housing Resources

How do Egyptians acquire land to build their homes, and how do they finance their housing needs? Who controls land prices and construction materials and makes them available to potential homeowners? How can one get a building permit? And who protects the public from corruption in local councils and the greed of some contractors?

The government should have a central role in all of the above; it is the duty of the state to provide the private sector, individuals and organized groups with the resources necessary for the production of habitat, starting from legal and financial tools, administrative mechanisms, and technical support, to providing land and raw materials at affordable prices. The provision of land is one of the most urgent and complicated housing issues in Egypt. Current policies for land pricing, selling mechanisms, land division, and geographic distribution in remote areas prevent the majority of citizens from acquiring affordable land that is close to urban centers with reasonable payment methods.

Informal Housing, Security of Tenure and Social Production of Habitat

Finding a reasonably priced housing unit in the city’s formal housing market is fighting a losing battle. Some may be lucky enough to secure one of the state’s public housing units in new urban communities constructed in the desert cities. However, living in these exurbs comes with its own challenges, such as increased daily transportation and living costs, limited job opportunities in these young cities, and the absence of a strong social network. These may be a strong enough deterrent to search for an alternative.

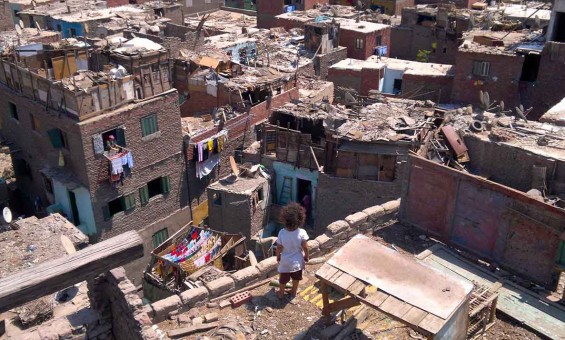

The lack of affordable housing options in the formal housing market that are close to the urban center’s job opportunities and services resulted in more than half of Greater Cairo’s residents living in self-constructed informal settlements that were built over the past few decades. This process of people taking matters into their own hands to solve their housing needs is called the Social Production of Habitat, or the process and product of community-based collective action to work together to improve their habitat And despite the fact that historically, this is how most cities were created, the residents of these informal settlements face many challenges, such as the state not recognizing them nor their right to continue living on these lands – especially if state-owned – disregarding the fact that many of these established communities grew and flourished for decades under the watchful eye of the government. The government has been reluctantly providing some basic services to these areas, however not recognizing their right to the land threatens the residents’ legal security of tenure, and not including them as part of city districts, denies them access to budgets and resources allocated to infrastructure and public services. Ultimately many of these residents end up living without enjoying their full citizenship rights.

What is discussed above is unfortunately not the condition of isolated individuals, but rather whole communities comprised of millions of residents in our cities. Greater Cairo alone has several communities that are battling these living conditions, such as Manshiyyit Nāṣir, `Izbit Khayrallah and many others. Seventeen percent of informal houses are built on state-owned land on the periphery of the city, all which could be subjected to evictions by the state.

Informal settlement residents have experienced a few successes in the last few years in their battles against state-enforced eviction. The Egyptian courts ruled that the government could not evict the residents of `Izbit Khayrallah and Ramlit Būlāq in Cairo and Qurasāya Island in Gīza. However, for every success story such as these, there are countless unknown cases of eviction and homelessness created as a result of the absence of clear constitutional articles and laws to protect millions of residents in this situation, and the enforcement of those laws.

Beyond the government’s role in directly providing housing units and establishing policies and particular regulations for the housing sector, a more comprehensive approach in dealing with new and existing urban communities, formal and informal is needed. The state should also support individual and organized efforts towards the social production of habitat by supplying resources needed, infrastructure and services to ensure that these communities with adequate housing.

Housing Crisis and Property Vacancies

For decades we’ve been hearing about the “housing crisis” in Egypt. One could easily assume this meant that there is a shortage of vacant units (formal, informal, or public housing) in our cities. On the contrary, our cities suffer from a significant under-utilization of built property, with a 25% vacancy rate in Cairo governorate, and 32% in Gīza and 35% and Alexandria governorates.2 This is due to the absence of effective property tax laws that govern property use and efficiently utilize vacant and speculative properties, which is related to the concept of the social function of property.

Development Regulations and City Planning

There are few clear and transparent building regulations, and little planning for infill developments that could maximize the utility of existing neighborhoods through providing infrastructure, public facilities and transportation, all which are directly related to the right to adequate housing. The reality is that many two- and three-story buildings are demolished throughout our cities and replaced with fifteen-story residential buildings, causing an overload on the area’s infrastructure and services. Without a sequential building development with infrastructure improvements, the quality of life for residents is bound to decrease and these areas will slowly lose the characteristics that made it attractive for incoming developments.

The Right to Adequate Housing and the Egyptian Constitution

Despite the fact that Egypt signed the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in 1967, the right to adequate housing only appeared in the Egyptian Constitution after the 25th of January 2011 revolution. The 2012 constitution, Article 68, states that:

Adequate housing, clean water, and healthy food are guaranteed rights.

The state issues a national housing plan. Its cornerstones are social justice, the encouragement of individual initiative, and housing cooperatives; The state uses state land for purposes of construction if doing so advances the public good and preserves the rights of future generations.

Housing experts criticized this article for two reasons:

First, the article does not clarify who is responsible for fulfilling the right to adequate housing, whether it is the government or other parties. It also does not obligate the state to provide adequate housing to citizens who cannot afford it, neither does it clearly outline the mechanisms for implementing the “the national housing plan.”

Secondly, the article does not clearly define what constitutes adequate housing, neither does it relate the definition of adequate housing in the constitution to relevant international conventions and agreements. This ambiguity leaves the opportunity to practices such as the displacement of informal settlements’ inhabitants to remote locations that are disconnected from facilities and places of employment, as well as the insecurity of tenure that leaves residents of many villages and cities vulnerable to forced evictions.

The constitutional amendments proposed by the Committee of 10 partially addressed these concerns by obligating the state to secure the right to adequate housing in Article 59, which reads as follows:

The State guarantees citizens the right to adequate housing, clean water, and healthy food. It is committed to adopting a national plan for housing, based on social justice, and to encourage self and cooperative initiatives in the field of housing, and to regulate the use of the state’s land for the purpose of urbanization in the public interest, and maintaining the rights of future generations.

Article 78 in the 2014 constitution elaborates on the above article, adding “safe and healthy” to requirements of adequate housing and that the national housing plan should “uphold environmental particularity,” however it does not elaborate on it entails. The state is obligated to provide basic facilities as part of the “comprehensive urban planning framework for cities and villages.” Informal areas are addressed for the first time in the Egyptian constitution in this article, obligating the state to devise a national plan that includes the provision of “infrastructure and facilities and improving quality of life and public health.” The article obligates the state to provide necessary resources to ensure implementing these goals “within a specified timeframe,” but does not outline which entity is responsible for quantifying this “specified timeframe” or will carry these implementations.

Below is the full text of Article 78:

The state guarantees citizens the right to adequate, safe and healthy housing, in a way that preserves human dignity and achieves social justice.

The state shall draft a national housing plan that upholds environmental particularity, and guarantees the contribution of individual and collaborative initiatives in its implementation.

The state shall also regulate the use of state lands and provide them with basic facilities, as part of a comprehensive urban planning framework for cities and villages and a population distribution strategy. This must be done in a way that serves the public interest, improves the quality of life for citizens and preserves the rights of future generations.The state shall draft a comprehensive, national plan to address the problem of informal areas that includes providing infrastructure and facilities and improving quality of life and public health. The state shall also guarantee the provision of necessary resources to implement the plan within a specified time frame.

The 2014 constitution has several other articles that address issues related to adequate housing. It prohibits arbitrary forced displacements (Article 63), which is a step forward from the previous constitution and can be utilized with mass displacements that occurred with Nubians and Bedouins, however it does not address other forms of forced eviction or the security of tenure issues discussed earlier. Article 20 commits the state to abide by “international human rights covenants and agreements ratified by Egypt,” which can be used to hold the state accountable to agreements related to international standards of adequate housing. The draft constitution also commits the state to “protecting rural inhabitants from environmental dangers” (Article 29). The provision of habitable housing to rural dwellers that protects from environmental elements and that are located in areas that do not endanger the health of its inhabitants can be argued to fall under this article.

A comprehensive definition of the right to adequate housing and an outline of the mechanisms and institutions that would implement this right are yet to be included in the Egyptian Constitution. This is in addition to the absence of an article that ensures the comprehensive security of tenure for residents, including its different forms recognized by the United Nations’ conventions, such as customary forms of tenure.

Global Examples of the Right to Housing

There are many developing countries that faced challenges similar to Egypt’s, including limited resources, fast population growth, and political turbulence, yet they have been able to draft their constitutions in a way that effectively protects the rights of vulnerable groups to adequate housing.

Countries such as Brazil (1988), Cape Verde (1992), Chechnya (2003), and Venezuela (1999) define adequate housing based on clear standards. The 1918 Uruguayan constitution, drafted long before social and economic rights were commonplace in constitutions, states in Article 45 that “hygienic and economical housing” is granted by law. If the Uruguayan constitution, written nearly a century ago, can define adequate housing for Uruguayans, surely Egyptians deserve to have these rights defined in their 2014 Constitution.

Venezuela’s constitution (1999) includes a comprehensive definition of adequate housing and sets a framework to secure the right of adequate housing for its citizens. Article 82 states that:

Everyone has a right to adequate housing, which is secure, comfortable, and hygienic, with basic essential services that include an environment, which humanizes family relations, neighborhoods and communities. The progressive realization of this right is an obligation, which is divided between citizens and the State in all respects. The State shall give priority to families and shall guarantee the existence of measures and access to social policies for credit and for the construction, acquisition, or improvement of housing, especially to families with limited resources.

Many constitutions do not obligate the state to directly provide adequate housing, but they clearly outline the mechanisms that provide it. For instance, Article 123 in Mexico Constitution (1917) obligates large-scale industrial and agricultural companies or other large-scale private or public enterprises to provide sanitary and comfortable housing for its workers through contributions to a national housing fund; it also stipulates creating a funding system to assist low-income workers in owning their units. As a result of implementing this constitutional article, the national housing fund continues to build hundreds of thousands of housing units yearly for workers using enterprise contributions and funds for workers. Similar articles can be found in the Brazilian (1988) and Guatemalan (1985) constitutions.

The Democratic Republic of Congo’s Constitution (2005) decentralizes housing and road construction from the national (ministerial) to the provincial (local) level, allowing each province to allocate resources and prioritize its housing and infrastructure needs on a local level.

Article 65 in the Portuguese Constitution (1976) obligates the state to ensure the accessibility and affordability of housing for everyone, and outlines the importance of cooperation between the state, local authorities and local communities to provide economic and social housing. It also gives citizens the right to participate in urban planning activities.

The Way Forward

Fulfilling the right to adequate housing is no small task and needs a clear definition of roles and expectations, as well as the cooperation of all sectors of society. The current housing article in the 2014 constitution prepared by the Committee of 50 covers two aspects of securing the right to adequate housing: 1) recognizing the right and 2) outlining the state’s role in ensuring that the right to adequate housing is fulfilled. Yet, to promote a more comprehensive adoption of this right that complies with international conventions and takes advantage of lessons learned from the international community, several issues need further attention:

- A clear, detailed right to adequate housing should reference international conventions and explicitly list adequate housing requirements, namely: legal security of tenure, availability of services, facilities and infrastructure, affordability, habitability, accessibility, location, and cultural adequacy.

- All people residing in Egypt, citizens or not, should enjoy the right to adequate housing without discrimination and irrespective of socioeconomic standing.

- The government’s role in the social production of habitat can be encouraged either through direct provision of housing for the very poor or providing support and institutional resources necessary for the production of habitat, including legal and financial tools, administrative mechanisms, and technical support, as well as providing land and raw materials at affordable prices.

- The state should recognize informal and self-constructed urban initiatives and facilitate legalizing settlements and supplying needed infrastructure and services. Government support of individual and cooperative initiatives in this field is also essential. The state’s obligation towards adequate housing should equally extend to new and existing urban communities, formal and informal.

- The state should protect security of tenure for all inhabitants without discrimination, recognizing different forms of tenure (formal, informal and customary) and handling cases of adverse possession on state-owned land in a practical manner that contributes to solving the adequate housing problems in those areas.

- The state should prevent forced evictions without a final court verdict and abide by international standards when carrying out such evictions.

1. United Nations. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. General Comment 4, The Right to Adequate Housing. E/1992/23, 13 December, 1991.↩

2. Calculated from 2006 CAPMAS data↩

- Header photo by Hossam el-Hamalawy published under Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Comments