The Right to an Adequate Standard of Living

What is The Right to an Adequate Standard of Living?

The right to an adequate standard of living is the unconditional right of all individuals to a “standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family” (UDHR, Article 11). It was first formulated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 to include food, clothing, housing, medical care, and other social services as well as “the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood beyond his control.” Special provisions are included to protect mothers and children. The Cairo Declaration on Human Rights echoes these provisions and also includes the right to education under the right to a “decent living” (1990, Article 17(c)).

Several other international declarations to which Egypt is party include the right to an adequate standard of living such as the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (1966, Article 11) and the Convention on Rights of the Child (1989, Article 25).

What is apparent from the definition of the right to an adequate standard of living is its complexity. It is a nexus of rights rather than one discernible right, intertwined with equal opportunity rights, such as those prohibiting forced labor or child labor. Furthermore, what does “adequate” mean? Some scholars have reduced “adequate” to a basic material issue in which an adequate standard of living means living above the poverty line. We find this highly problematic. There are hundreds of thousands of people in Cairo alone who may live above the poverty line who do not have access to healthcare, adequate housing, public utilities, food, and education. In this case “adequate” is defined by cultural context, time, and place and is a standard that rises in tandem with the fortunes of society as a whole.

This discussion is by no means exhaustive, but instead focuses on the elements of the right which are most germane to Tadamun’s mission. The right to housing (as well as its implications for public utility provision including water and sanitation services) is fundamental to the right to an adequate standard of living. We have discussed this right elsewhere on our website and will focus here on the other components of the right to an adequate standard of living.

The Right to Adequate Food

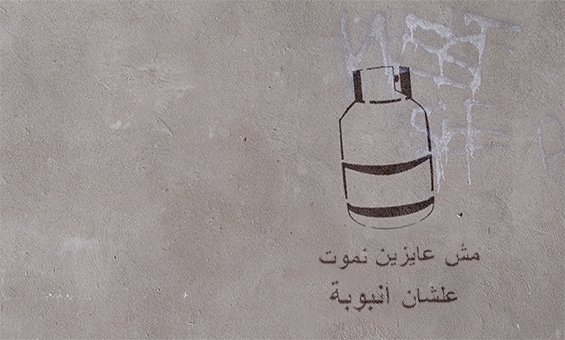

Cities shut down without an adequate food supply for its population. People take to the streets, economic activity halts, and governments sometimes fall. The Bread Riots of 1977 saw hundreds of thousands of people in cities across Egypt protest the IMF and World Bank imposed policies to end subsidies of basic foodstuffs. It is no coincidence that the demand for bread was the first of the three overarching demands of the 2011 Revolution. In this context, bread was symbolic of a host of other economic issues, but the right to adequate food was at its heart since much of Egypt’s population could no longer afford to put food on their table. Everyone, without discrimination, should have physical and economic access at all times to adequate food. Governments have a core obligation to take steps to mitigate and alleviate hunger. The right to adequate food includes the availability of food, physical and economic accessibility of food, and the cultural acceptability of food.

The right to food has several implications for the built environment. First, is related to food supply. Egypt must protect the agricultural lands surrounding Cairo. Over the past 40 years, vast amounts of agricultural land have been lost to the expanding urban fabric of the city. Much of this is due to the expansion of informal settlements. While those who live in informal settlements cannot be blamed for moving into these homes for lack of any reasonable alternative in the city, the government must do a better job at improving the housing situation in Cairo to reduce the loss of this precious natural resource.

Second, public markets are crucial to the function of the city. Neighborhoods must have access to markets that sell quality food at reasonable prices. As the city has developed, there has been considerable real-estate pressure on informal markets to formalize, which in turn, impacts the prices of food. Formalization itself is not bad, however, the state must take measures to protect consumers against spikes in the price of food at the community level as well as the state level.

The Right to Work

The right to work is the right of everyone to the opportunity to earn a living to support oneself and one’s family. While the right to an adequate standard of living is unconditional and applies to everyone equally regardless of their economic contributions to society, it is through work that most individuals may realize an adequate standard of living. The right to work has social implications as well. Although these social implications vary greatly among professions, gainfully employed individuals are more highly respected in their communities and have a stronger sense of self-worth than individuals who are victims of unemployment. Individuals who earn a living have the satisfaction of being able to provide for themselves and their dependents.

Workers’ movements have had a significant role in shaping policies around the right to work in Egypt. They played a critical role in normalizing protest against the Mubarak regime in the eyes of the public during the early 2000s, and since the 2011 Revolution, workers’ movements have taken a prominent role on the national stage. Labor movements mobilized against the privatization of state enterprises that began with Anwar Sadat’s Open Door Policy. The earliest of these movements up through the 1990s were weakened in large part by the state-run Egyptian Trade Union Federation (ETUF), Egypt’s only legal trade union organization, as well as the government’s willingness to use excessive force. Even though privatization kept apace under the Mubarak government, including the 1991 restructuring agreement with the IMF, there were only an average of 27 protests per year in Egypt between 1988 and 1993. This figure rose to 118 between 1998 and 2003 as privatization efforts accelerated, and exploded to 265 in 2004 due to the accession of Prime Minister Ahmad Nazif who led “the government of businessmen.” The movement against Nazif’s policies ultimately expanded to nearly every part of the labor force in Egypt—all industries, public services, transportation, professionals, and civil servants (Beinin 2012). Between 2007 and 2010, there were more than 626 labor protests each year, setting a strong example for the Revolution to come (Abdalla 2012).

The Right to Safe Water

The right to safe water is implicit in the rights to adequate food, adequate housing, and health. Without access to safe water, these rights are unattainable therefore undermining the right to an adequate standard of living. General Comments 15 of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) states, “The right to water contains both freedoms and entitlements. The freedoms include the right to maintain access to existing water supplies necessary for the right to water, and the right to be free from interference, such as the right to be free from arbitrary disconnections or contamination of water supplies. By contrast, the entitlements include the right to a system of water supply and management that provides equality of opportunity for people to enjoy the right to water.”

Fair distribution of water and water scarcity has always been a challenge to the Egyptian state. Between 2007 and 2008 Egypt witnessed about 40 protests, dubbed the “Water Revolution,” that were related to distribution of drinking water (Reem 2007). When more than 20,000 people in the Ubur area in the city of Ismailia were suffering from scarcity of water, 40,000 citizens of al-But and Isa, Damiatta were forced to use contaminated canal water for bathing and household use, and children from Abu Rudeis, South Sinai were suffering from skin disease because they bathed with contaminated water due to water scarcity, the Egyptian government granted a Canadian petrochemicals company 105 million cubic meters of clean water for only 3 million EGP per year (Ismail 2008). While most of Cairo’s residents have access to safe water, its quality is often compromised, particularly in outlying villages and in the informal housing areas. (See our case study of Nahia Village for further detail about an initiative to provide safer drinking water.)

Adequate Standard of Living in Egypt

The Egyptian Constitution (2012) guarantees different elements of the right to an adequate standard of living in several articles.

- Article 68 guarantees “adequate housing, clean water, and healthy food.”

- Article 10 guarantees free maternal and child health care as well as special care and protection for female breadwinners, widows, and divorced women.

- Article 14 obliges the state to enhance the standard of living, eliminate poverty and unemployment, ensure equitable distribution, and establish a minimum wage that guarantees decent living standard and maximum wage in civil service positions.

- Article 15 obliges the state to guarantee food security.

- Article 62 states that healthcare is a right and should be provided to all citizens with just and high standards and free of charge to the poor.

- Article 66 articulates that the state shall provide social insurance services to all citizens and protect the incapable, unemployed, and elderly.

- Articles 71 and 72 oblige the state to provide care for children and youth and provide people with disabilities with social, economic, and health care support.

There indeed is a gap between what this Constitution promises and the reality in Egypt. Keep in mind that the Constitution is a normative document, principles against which Egypt can measure itself. Also keep in mind that the right to an adequate standard of living does not require the state to provide an adequate standard of living, but to take action to help individual citizens realize this right.

How can they do this? Three ways. First, the Egyptian state is obligated to first respect these rights by ensuring that no government action will restrict access to housing, food, healthcare, education or other social services. (In other words, don’t make things worse.) This means no forced evictions, no closures of public schools or hospitals, and no demolishing communities. Second, the government must protect these rights by preventing non-state actors such as individual citizens, community groups, private business, foreign investors, or the military from violating other citizens’ rights. (Don’t let others make things worse.) This means enforcing restrictions on polluting, enforcing land use laws, honoring squatters’ ownership of their land, maintaining security in public places, and ending corruption. Finally, the government must take steps to fulfill these rights by creating the economic, political and social environment in which the rights to an adequate standard of living can be realized. (Make things better.) In other words, more programs which promote equal opportunity for education, equitable distribution of government services, livable wage initiatives, etc.

The Way Ahead

The right to an adequate standard of living is one of the major rights Egyptians have struggled for in the last few decades. It is also an area where civil society is actively engaged. Enjoying an adequate standard of living requires affordability of housing, food, healthcare, transportation, etc. The high cost of living in urban areas like Cairo relative to annual income is a major concern to Egyptians living in cities. Not only providing an adequate standard of living has always been a challenge in Egypt, but also supervising the violation of this right has never been well established. There is no legal procedure in Egypt for personal complaints about the violation of the right to an adequate standard of living. While Article 68 of the Constitution clearly states that access to adequate housing, clean water, and healthy food are given rights, it does not elaborate on how individuals can hold authorities responsible for providing and not violating these rights. With so many social and economic challenges ahead and lack of a clear legal procedure to hold officials accountable, enjoying an adequate standard of living continues to be a challenge for the Egyptian society.

Work Cited

Abdalla, Nadine. 2012. “Egypt’s Workers: From Protest Movement to Organized Labor.” Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP) Comments 30. October 2012. Retrieved from http://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/comments/2012C32_abn.pdf (Last accessed: June 25, 2013)

Beinin, Joel. 2012. “The Rise of Egypt’s Workers.” The Carnegie Papers. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. http://carnegieendowment.org/files/egypt_labor.pdf (Last accessed; June 27, 2013)

Ismail, Abdel-Mawla. 2008. “Drinking Water Protests in Egypt and the Role of Civil Society.” In Reclaiming Public Water: Achievements, Struggles and Visions from Around the World. Brid Brennan (eds). Third Edition. Corporate Europe Observatory.

Leila, Reem. 2007. “Parched and protesting.” Al-Ahram Weekly. 2-8 August 2007, Issue No. 856. Retrieved from http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/2007/856/eg10.htm (Last Accessed June 24, 2013)

World Food Programme. 2013. “The Cost of Hunger in Egypt: Implications Child Undernutrition Social Economic Development.” World Food Programme series of The Cost of Hunger in Africa (COHA). June 2013. Retrieved from http://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/ena/wfp257981.pdf (Last accessed: June 24, 2013).

Comments