Urban Mobility in Cairo: Governance and Planning

Urban Mobility: More than Just Building Roads

It is no secret that getting from Point A to B in Cairo is an arduous journey. Hour-long traffic jams, accidents, overcrowded public transportation systems and limited parking spaces aren’t a novelty to the city. However, to view Cairo’s transportation woes as the result of physical traffic constraints alone, such as the supply and design features of the road network or parking capacity would be reductionist. Urban mobility is a vital aspect of the city and is shaped by complex interactions: on the political level conflicting interests have to be navigated while taking into account large economic impacts, financial constraints and environmental consideration; and on a technical level, mobility is the result of the interaction of different sociotechnical systems (Cascetta et al. 2007). As these complex dynamics are not usually well-studied and understood, responsible entities often resort to traditional solutions such as infrastructure development or the improvement of conditions for the private car. It is, therefore, vital to analyze Cairo’s transportation problems as part of the broader urban governance structures and to view them against the backdrop of fragmented local authorities (Cook 1985). This article aims to create a better understanding of the institutional structure for urban transport in the Greater Cairo Region (GCR) and the problems that arise from the current institutional configuration.

The Institutional Setup for Mobility in GCR

Traffic Administration

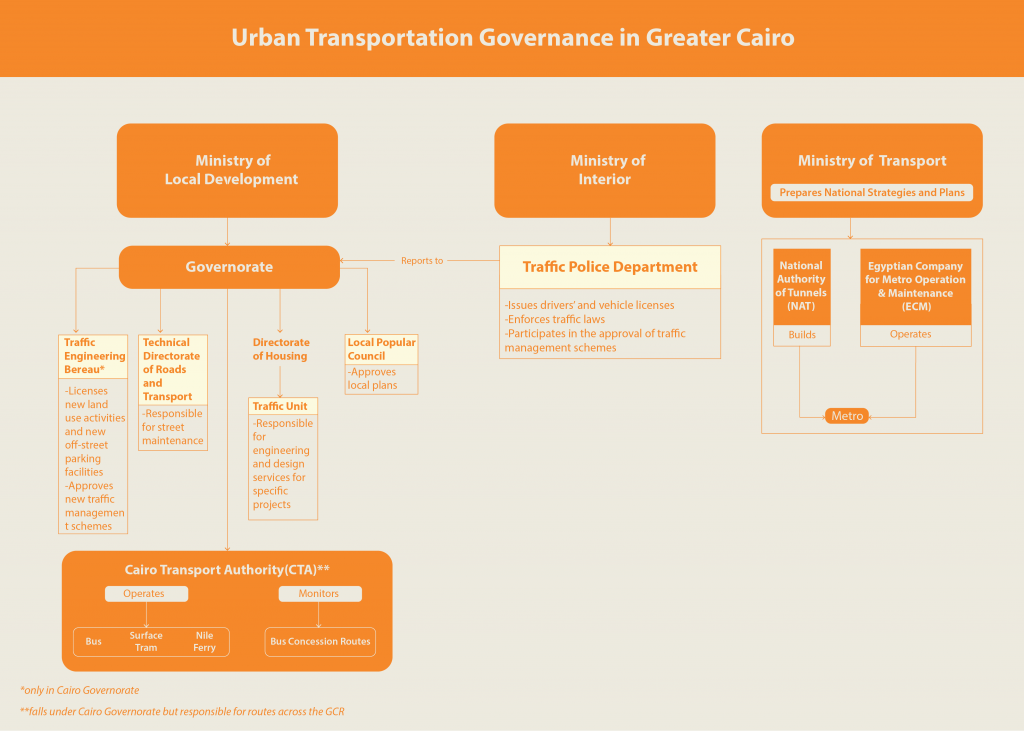

A multitude of actors are involved in the decision-making, operation, and monitoring of the transportation sector. Although, the GCR is publically recognized as one city, administratively it is divided into the governorates of Cairo, Giza and al-Qalyūbiyya. Within each of these governorates, there is a local technical Directorate of Roads and Transport which falls technically under the Ministry of Transport (MoT), but administratively under the governorate. The directorate is responsible for street maintenance. The Traffic Unit within the Directorate of Housing and Utilities in the governorates is responsible for engineering and design services for specific projects. The directorate of Housing and Utilities falls administratively under the governorate and technically under the Ministry of Housing, Utilities and Urban Communities. There is additionally a Traffic Police Department within each governorate, which technically falls under the Ministry of Interior and is not under the direct supervision of the Governor but reports to him nonetheless (World Bank 2000). The Traffic Police departments issue drivers’ and vehicle licenses and enforce traffic laws. They also participate in the approval of traffic management schemes, such as speed limits and parking restrictions, the monitoring of which is then done by the police departments. Microbus routes are licensed by the governorates in which a route runs in coordination with the relevant traffic police departments. Additionally, the Cairo Governorate (CG) has a Traffic Engineering Bureau with the main responsibility of assessing the impact of new land use activities on traffic, licensing new land use activities and new off-street parking facilities, as well as approving new traffic management schemes.

Operators and Regulations

In terms of operators, the Cairo Transport Authority (CTA), even though it falls under the responsibility of CG, is a major mass transit operator in GCR whose services extend to the governorates of Giza and al-Qalyūbiyya. CTA operates its own busses, in addition to busses of its wholly owned but separately governed subsidiary, the Greater Cairo Bus Company. It additionally monitors concession routes granted to a number of private operators in the CG, whereas Giza Governorate monitors the concession routes running on its territories (World Bank 2000; DRTPC, 2009). Additionally, CTA operates Nile ferry lines and runs what remains of the tram system, after the governorate of Cairo removed more than 60% of it since October 2014.

The CTA is financed from fare revenues and the state budget through subsidies that allow it to retain a low fare price. The National Authority of Tunnels (NAT), the entity responsible for all tunneling projects in Egypt, constructed the metro, arguably the most effective mode of formal public transport in GCR. Upon their construction the metro lines were transferred to their operator, the Egyptian Company for Metro Operation and Maintenance (ECM), a public company owned by the Ministry of Transport (DRTPC 2009). The construction of the metro was financed through the French Development Agency and the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). Only a small portion of the operational costs, estimated at 11%, are covered by fare revenue. The majority of the operational costs are covered from the state budget, with investments in the metro system reaching 91.8% of the funds allocated to public transport from the state budget.

Decision-Making and Planning Frameworks

Ministry of Transportation is responsible for preparing national strategies for transport, prioritizing the needed transportation projects and determining their cost, financing and operations mechanisms, as well as their execution timelines. National level projects need to be approved by the Parliament, while mobility-related decisions and projects on the governorate level are approved through the governorate’s Local Popular Council. The Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency coordinates with other entities such as the MoT or the CG to ensure that negative environmental effects from transportation are minimized, particularly on air quality. Their efforts include the vehicles exhaust inspection programs in collaboration with the governorates’ police departments, the scraping and replacement of old vehicles program and the promotion of compressed natural gas as a form of cleaner fuel.

Shortcomings in the Current Institutional Set-Up

Disaggregate Planning and insufficient integration of the services

This institutional setup leads to unsatisfactory transportation planning and traffic management and inadequate service delivery of public transport systems. Firstly, the multitude of actors causes a lack of clarity in the allocation of tasks. For example, within the Cairo Governorate there is no clarity over whether the Cairo Traffic Police or the Cairo Traffic Engineering and Planning Bureau have the ultimate jurisdiction over traffic planning and traffic engineering design (World Bank 2000). Additionally, with the responsibility of planning for public transport system divided among MoT and NAT for rail-based transport and the Cairo Governorate for road-based modes of transport there is little room for integrated transportation planning due to the lack of one single agency responsible for developing integrated transport plans. This is magnified by the lack of coordination and communication amongst the different agencies. A lack in institutional cooperation translates into little to no integration among the different transportation modes in terms of scheduling, routes, and fares to maximize the available resources, as each operator plans its way of operation with disregard to other operators (World Bank 2000).

The lack of modal integration impacts people’s accessibility, their satisfaction and the number of people using public transportation. Taking fares as an example, currently, a passenger who uses multiple forms of transport must pay separate fares. This can constitute a financial burden and often leads to passengers choosing a longer route on one mode of transportation rather than a fast multi-mode option. For transportation systems to be truly integrated they should allow people to choose the most convenient transport modes to reach their destination without having to worry about paying multiple fares.1 From an economic perspective, the lack of integration also impacts the fare revenues and operating costs, which in turn affects the financial viability of public transport projects. In Cairo, fare unification – the joint coordination of fares for the different modes of transportation – has been an often talked about reform measure, which however, has not yet been implemented. According to urban economist David Sims (2010), the lack of coordination can be traced back to the fact that “most Egyptian government bodies, persistently behave like small children, separate fiefdoms, each jealously guarding its own turf.”

Shortcomings in the supply and integration of public transportation systems are compensated for by informal modes of transportation, which first appeared in the mid 1970s. In 1977, a law allowed the operation of 11-seat microbuses on a number of fixed routes. A decade later 14- and 18-seat micro- and minibuses were allowed and the number of licensed routes reached 133 routes. By 1998 there were 27,300 minibuses running on more than 650 routes according to reports by the Cairo and Giza traffic administrations (Sims 2010). In recent years other informal modes appeared such as the tuk-tuks (motorized rickshaws). Those informal modes of transport succeeded in attracting passengers, the percentage of passengers using microbuses increased from 15% to 25% from 1996 to 2001, while the percentage of those using formal buses dropped from 31% to 21% during the same time (GOPP 2012).

Informal modes of transport are often attracted to locations with high numbers of potential passengers such as metro stations, major road intersections, and commercial areas. They, additionally, act as feeders to many metro and bus stations, as they collect passengers from different locations and deliver them to a transfer point where they continue their journey. Microbuses significantly increase people’s accessibility in the city as their networks extend far beyond the reach of public buses especially within informal settlements which are never served by public transportation lines (bus, metro, or tram).

Routes and fares for microbuses are set by the governorates’ traffic departments and the relevant traffic police departments (World Bank 2000). However, the very lax monitoring leaves ample room for drivers to alter both, with fares often fluctuating within a range depending on the distance travelled and the driver (Sims 2010). This leaves passengers at the mercy of drivers. For instance, after fuel prices rose in 2014 microbus drivers increased the prices 50-100%, while the fares for public buses remained the same. The minimal control and monitoring of the state also encourages drivers to engage in dangerous behaviors such as speedy, erratic driving which compromises the safety of passengers. Despite the fact that microbuses are licensed, they are still considered informal by planners as they are not part of an integrated transportation plan.2 Other informal modes of transport such as tuktuks are not regulated by the authorities at all and are mostly used for short travel distances within neighborhoods, particularly in popular and informal areas, as well as new cities. However local administrations in some higher income neighborhoods, such as Maadi, have banned their use.

Missing linkage between transportation and urban planning

Urban mobility is both an outcome and a shaping factor of how cities take form. Compact urban configurations with a closer mix of activity make cities more accessible, and high population densities are essential for providing cost-effective urban transportation. Similarly, the introduction of urban transport networks affects the urban structure and densities. For example the completion of the first metro line (Ḥilwān (southern Cairo) – al-Marg (northeast Cairo)) helped the urban densification along its corridor (Metge 2000). On the other hand, urban sprawl lengthens trip time and increases the reliance on private vehicles, while the low densities reduce the economic viability of public transportation projects.

This close relationship was once recognized in the Egyptian context. A successful example of the integration of town-planning with transportation planning was the creation of Heliopolis, the first large-scale town-planning operation which took place on a semi-desert area 10 km away from the Central Business District by Baron Empain in 1906 (Metge 2000). The integration of a tramway network was central to the development of Heliopolis. Creating an easy mobility link to the Central Business District wasn’t an afterthought but was rather discussed in the early design stages. Similarly, the development of Shubrā and Rūd al-Farag to the North of the Central Business District was strongly tied to the opening of new tramway lines in 1902 and 1905.

Currently, and despite the multitude of actors involved in the planning and decision-making for transport projects, long-term transportation planning is not integrated with strategic urban development planning (World Bank 2000). The lack of a counterpart to the General Organization for Physical Planning (GOPP), which is responsible for large land-use and urban development plans, makes long-term coordination between transport and urban development plans non-existent or rather ad-hoc (Ibid). The unsuccessful integration between the two disciplines has perhaps been most evident in the planning for the numerous new satellite cities built around Greater Cairo. The construction of these cities started after the 1970 master-plan aimed to contain the urban sprawl through the creation of the Ring Road and the development of new satellite cities to accommodate the urban expansion and thus, de-concentrate industry, housing, and social facilities to the periphery of the city. The development of new cities did not meet the set targets, neither in terms of number of their inhabitants nor their ability to attract the targeted middle and/or poor segments of the population. One important drawback in the inception of these cities has been the scarcity of public transportation within them or connecting them to Cairo. Residents complain that formal buses are limited in numbers and often run late and are slow. On the other hand, informal minibuses constitute a financial burden on passengers as their prices fluctuate between different operators and are often perceived as dangerous due to drivers’ erratic driving. Announcements and plans to connect new cities such as Shaykh Zayid and 6th of October City (West of Greater Cairo) to downtown Cairo through electric rail and/or the metro have not materialized. As a result, private cars are a precondition for easy mobility between the new cities and Cairo, making them suitable and convenient for mostly wealthy residents who own private cars. In addition to their limited accessibility to non-car owners, the new cities constitute a burden on Cairo’s existing transportation network. Despite the success of some of the cities in establishing an economic base, they have not emerged as independent from Cairo. This is reflected in a significant portion of the new cities’ population commuting to and from Cairo, with an estimated 238,000 trips to 6th of October City and Shaykh Zayid City on a daily basis which adds to the city’s congestion and environmental pollution (GOPP 2012).

Lack of Strategic Planning

Current transportation projects and plans seem rather ad-hoc and ill-thought-out, and without serious evaluation of feasibility studies (Sims 2010). The lack of long-term strategic planning can be attributed to a number of factors. In an interview with Dr. Ahmed Mosa, transportation planning expert, explains that transportation planning in Cairo is based on the 1991/2001 study of the metro line by French engineering group SYSTRA, as well as the 2002 Cairo Regional Area Transport Study (CREATS) by JICA.3 However, the execution of the projects in the plan are almost impossible due to the lack of a single entity that can plan and prioritize the projects which are then awarded to another agency for execution. With both the MoT and the Cairo Governorate as planners and service providers, the planning and execution roles become blurred and long-term integrated strategic planning becomes difficult.

The other issue relates to funding as formal operators primarily rely on state budget for funding. They usually compete with other ministries and departments for the state’s limited funds, making funding limited. As a result, long-term strategic planning is made difficult and operators are focused on the day-to-day operations rather than on long-term plans.

Lastly, a World Bank Report (2000) iterates that there is little capacity in the current administrative structure for strategic long-term transportation planning. Specifically, the report claims that staff of the Traffic Police is extensive but undertrained, while Traffic Bureaus are understaffed. Discussions with the academic community have revealed that the inadequate staffing is a budget and commitment problem rather than a structural or institutional one as Egypt’s educational system produces many qualified traffic engineers, which are not currently utilized (Ibid).

Government Reform Efforts

Calls from international donor organizations for institutional reform and the creation of a coordinating mother agency have long existed. They first surfaced in 1987 and then again in the 1990s and 2000s in a number of studies (DRTPC 2009). However, efforts to create a single supervisory coordinating agency have been in vain as it is difficult to bring the multiple agencies which need to be coordinated and which fall under various authorities as previously illustrated under a single supervisory entity (Ibid).

The creation of the Greater Cairo Transport Regulatory Authority (GCTRA) is a case in point. GCTRA was created by a Presidential Decree in November 2012, as a result of a JICA recommendation. The Transport Regulatory Authority is tasked with overseeing transport issues in the GCR, and ensuring effective coordination and efficiency in planning and implementing investments in the sector. Despite having been created over four years ago, the authority has only been conducting stakeholder meetings and analyses thus far. It is likely that this is the case because a portion of the new authority’s mandate overlaps with activities of existing bodies. The Minister of Transportation, Dr. Galal Said, announced that the ministry has recognized this problem and that the authority will be activated by a new Presidential Decree to assume its responsibilities. As some transportation experts have iterated in a number of transportation conferences which took place this year, such as Egypt Urban Futures or Sustainable Transport in Egypt, GCTRA’s position in the public administration structure as a subsidiary of the MoT is an obstacle to it having an effective role, as GCTRA’s work will necessitate it to assume the responsibilities of other entities on the same hierarchical level as the MoT. This will make those institutions unlikely to cede their responsibilities to the new entity. Some, therefore, believe it is necessary for the entity to be affiliated to an even higher entity in the hierarchical governance structure, such as the cabinet or the presidency.

TADAMUN’s Vision

It is unrealistic to expect that we can achieve the right to adequate urban mobility in the GCR without significantly increasing the investments in the sector. However, it is also necessary to treat transportation problems as more than only technical problems, which require investment-intensive technical solutions, and to view transportation problems also as political challenges. The mobility problems facing Greater Cairo – and most Egyptian cities – are largely related to how priorities are set, decisions are made, and plans are implemented. Currently, transport solutions are piecemeal and ad-hoc. There are no clear criteria upon which priorities are set or funds allocated. Despite the heavy reliance on public transportation and walking as the major mode of mobility in the city, investments keep flowing to accommodate the private car. Of the national budget spending on transportation for 2015/2016, only 18% was allocated to public transportation (metro, buses and trams), whereas 24% went to local roads and bridges. Are those the best decisions to promote the right to adequate urban mobility and create an accessible city for all, regardless of physical or financial ability, age or gender? Similarly, out of the public transport budget a whopping 91.8% is spent on the underground metro with only 8.2% going to public buses. How and why these investment decisions are made remains unclear.

This comes as no surprise given the lack of true democratic representation and the high degree of centralization, which leaves planners, academics and architects with little room to determine the outcomes of planning processes with the authorities. Central decisions are often made with little regard to societal, economic and environmental criteria with little input from stakeholders and insufficient attention paid to alternative solutions (World Bank 2000). Indeed, often redevelopment and transportation projects are kept as “secret” and only appear when their physical construction begins (Sims 2010). It is, therefore, important to establish transparent decision-making processes with clear criteria, such as cost-effectiveness, economic and social returns, and environmental impacts to set planning and investment priorities (World Bank 2006). It is equally important to encourage the participation of all stakeholders in the decision-making process to ensure truly integrated planning.

1. For more on the integration of transport services: Eighteenth Annual Report and Resolutions of the Council of Ministers, 1971.

2. Interview conducted with Dr. Ahmed Mosa on November 17, 2016.

3. Interview conducted with Dr. Ahmed Mosa on November 17, 2016.

Works Cited

Cascetta, Ennio, Francesca Pagliara, and Andrea Papola. 2007. “Governance Of Urban Mobility: Complex Systems And Integrated Policies.” Advances In Complex Systems, 10 (2), 339-354.

Cook, David B. 1985. “Transport Problems in Cairo”. In The Expanding Metropolis: Coping with the Urban Growth of Cairo, edited by Ahmet Evin. Singapore: Concept Media/Aga Khan Award for Architecture.

General Organization of Physical Planning (GOPP). 2012. “Greater Cairo Urban Planning Strategy.”

Metge, Hubert. 2000. World Bank urban transport strategy review: The case of Cairo, Egypt. Washington DC: World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/937421468262537412/World-Bank-urban-transport-strategy-review-the-case-of-Cairo-Egypt-executive-summary

Sims, David. 2010. Understanding Cairo: The Logic of a City Out of Control. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.

Development Research and Technological Planning Centre (DRTPC). 2009. “Research Study on Urban Mobility in Greater Cairo: Trends and Perspectives.” https://planbleu.org/sites/default/files/publications/greater_cairo_final_report_0.pdf

World Bank. 2000. “Cairo Urban Transport Note.”

World Bank. 2006. “Greater Cairo: a Proposed Urban Transport Strategy.” http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/892401468258874851/Egypt-Greater-Cairo-a-proposed-urban-transport-strategy

Comments