Urban Mobility: Transforming Minibus-Taxi Operations in Johannesburg

Informal Transportation in the Global South

Characteristics of the Informal Transportation Sector

While there is no precise, agreed upon definition of what constitutes informal transportation, most definitions place it as a privately-owned counterpart to formal public transportation systems which benefits from relaxed or non-existing regulatory frameworks (Salazar-Ferro 2015). They often lack official necessary permits for market entry or do not meet fitness standards which ensure that vehicles fulfill required safety standards (Cervero 2000). However, even some which are registered are still considered informal by some planners as they are not integrated in a governmental transportation plan.

The organizational and operational characteristics of informal transportation services provided vary widely between cities as the regulatory frameworks, physical extent of cities, presence of other transportation modes, and population densities differ (Cervero 2000). In terms of ownership, informal transportation businesses tend to be privately-owned by individuals, cooperatives, or small, medium and large companies. However, sometimes they are even owned and run by government officials as side businesses (Behrens et all. 2016). Their daily operations are conducted by owners who also function as drivers, owners who hire and manage drivers, or owners who lease their cars to drivers in exchange for a fee or a part of the daily earnings. Often informal transportation services such as vehicle rotation on routes is managed and coordinated by operators associations. In terms of the fleet, operators deploy a range of vehicles from 3 wheelers to shared sedan taxis, mini buses and full-size conventional buses (Wilkinson 2008).

Strengths and Weaknesses of the Informal Transportation Sector

The informal transportation sector is in many cases what keeps cities of the Global South moving. Studies have shown that 99% of households in the poorest African countries do not own a car and have to rely on public transportation for access to schools, hospitals, and employment opportunities (Cervero 2000). In cities where official public transportation systems are non-existent or unreliable people have to rely on informal public transportation to fulfill their mobility needs which cannot be met through walking or cycling, making informal transportation systems’ expanded geographic coverage one of their main advantages. Other benefits of informal transportation systems is their demand-responsiveness. Through their adaptability and flexibility in terms of frequencies or schedules they are able to quickly respond to changes in demand (Behrens et al. 2016).

From an economic perspective, informal transportation services create employment opportunities directly for the drivers or indirectly for the mechanic workshops, petrol stations, and spare part manufacturers, among others, thereby positively affecting the economy. Additionally, informal service providers are considered as entrepreneurs who contribute to economic development by satisfying their own and their families’ needs as well as re-investing the profits they make in their business in the transportation sector or in other sectors (Behrens et al. 2016).

Despite all of the advantages associated with informal transportation they exhibit a number of negative externalities which make them problematic for planners and the authorities. Safety is a prime concern. Often on their quest to increase their profits by increasing the number of passengers, drivers exhibit aggressive and dangerous driving behavior compromising the safety of passengers. Informal transportation modes exhibit a relatively poor safety record. The cutthroat competition for customers additionally leads to disruptive operational inefficiencies such as competing on prime routes while other routes remain unserved or driving excessively long routes forcing commuters to spend longer times in traffic. These practices, in addition to the unrestricted market entry often lead to an oversupply of service providers significantly contributing to chronic traffic congestion in cities.

Lastly, harmful business practices such as lack of investment in vehicle maintenance and replacement mean vehicles are often old and decrepit, uncomfortable for passengers, and an environmental disaster in terms of their air pollutants emissions (Cervero 2000 and Wilkinson 2008).

The different forms of formalization

Despite the significant role they play for urban mobility in the Global South, informal modes of transportation are often viewed as an obstacle to modernization of public transportation services, and therefore require transformation. This transformation should focus on their business structure and organization on the one hand, and operations, such as the routes, schedules frequencies and fleets, on the other (Salazar-Ferro 2015). Approaches to this transformation vary widely. While some researchers believe processes of self-regulation by informal operators’ associations can tackle problems associated with informal transportation, others claim that associations are more likely to respond to the demands of their own members and ignore those of passengers with the lack of public oversight. Additionally, self-regulation in specific issues such as the rights to operate on specific routes may not be the answer as it is often enforced through violent means such as attacks on rival operators (Wilkinson 2008).

Generally, three types of approaches can be distinguished for the transformation of informal public transportation systems (Salazar-Ferro 2015). The first attempts the city-wide and often immediate transformation of the city through the replacement of informal modes of transportation with new or existing formal modes. The second approach focuses on the gradual transformation on a corridor-by-corridor basis. In this approach a dual system is created where formalized informal transportation runs alongside informal modes. This reform can be as aggressive as the complete substitution of informal modes to the formalization of operators through the creation of operating companies. Lastly, the transformation can come about by reorganizing informal modes through upgrading the informal fleet in fleet renewal schemes, introducing regulations regarding operations or business structure, or similar interventions (ibid). The case study we have chosen for this article falls within the second family of approaches in which the City of Johannesburg planned to substitute the services of minibuses on a major corridor with a BRT system, while incorporating existing informal mini bus operators in the operations of the planned BRT route.

Case study: Johannesburg

History of Informal Transportation Johannesburg

Johannesburg, located in the Gauteng Province is the province’s political capital and home to about 4 million people (McCaul and Ntuli 2011). Even though it is the economic center of South Africa, the city exhibits extreme income inequalities and 63% do not own a car (Allen 2011). Despite the presence of formal public transportation buses, South Africa’s privately owned 15-seat minibus taxis, also known as “combis” thrive. 2003 statistics estimate that there are 130,000 minibus taxis throughout South Africa, with 60% of commuters using their services (Venter 2013).

The development of public transportation in Johannesburg was shaped by the apartheid system, which existed between 1948 and 1994, and the spatial planning policies it produced. Under the apartheid system African workers were housed in townships approximately 25-30 km away from the central business district and white areas to limit the interaction between them, but close enough to offer their services as labor in the central areas. During that time public transportation services, associated with low-income non-white populations were sporadic and unpredictable. State-run buses and train routes and schedules were rigid and made every day commuting time-consuming, tiring and expensive. Informal transportation systems, thus, evolved as a demand-driven response to the people’s need for reliable transportation services to access areas in which they could not reside, but which they needed to access to work. When the first modes of minibuses emerged in South Africa prior to 1977 they were operating illegally, as existing apartheid laws hindered non-white males from obtaining the formal requirements for issuing taxi operating licenses (Woolf and Joubert, 2013). As a result non-whites who owned a car started giving people lifts in exchange for a small fee. This sometimes landed drivers and passengers alike in prison. Non-white entrepreneurs, nevertheless, found ways to circumvent the laws and to operate minibuses. After the 1976 Uprising the Road Transportation Act of 1977 permitted the use of 9-seater minuses to be used as shared taxis (Behrens et al. 2016). The Transport Deregulation Act of 1988, which further facilitated the entry of new operators, led to a 2500% increase in the number of minibus-taxis between 1985 and 1990, particularly in new areas, informal settlements, and residential areas not served by buses or trains (McCaul and Ntuli 2011).

The deregulation act has led to an oversupply of minibus-taxis paving the way for cut-throat competition between drivers resulting in poor vehicle and driving standards. This competition against the backdrop of the absence of any formal mechanisms for the coordination between drivers or the allocation of routes led to the emergence of voluntary area-based operators associations. To join an association a driver would have to pay a fee in exchange of the rights to operate on a specific route. In that sense associations did not function as representative bodies for the rights and interests of their members but rather as a mechanism to enforce ‘property rights’ to the routes since they were not enforced by the state. This arrangement was accompanied by the use of violence to settle disputes. Intense rivalries often led to full-fledged gang warfare. In Johannesburg there have been cases where operators have boarded the back-seats of rivals’ minibus-taxis and shot them in the back in what has been dubbed “death from the back seat strategy” (Ceervero 2000). In 1993, 330 deaths were attributed to taxi violence. This has led to the perception of the minibus-taxi industry as dangerous, illegal and operating with impunity (Venter 2013).

Minibus-taxis in Johannesburg traffic – Photo by: itdp

Passengers waiting to board minibus-taxis – Photo by: Rafiq Sarlie

Minibus-Taxi Industry Formalization Attempts

Since the mid-1990s and the country’s transition to a post-apartheid regime, South African transportation policy had two main goals. Firstly, to prioritize public transportation provision and non-motorized transportation over the use of private vehicles to serve the mobility needs of disadvantaged segments of society. Secondly, the implementation of effective demand management strategies, such as dis-incentivizing the use of private vehicles, and promoting public transportation oriented land-use patterns (Wilkinson 2010).

At the same time the government recognized the need to effectively engage with the minibus industry and set up a National Taxi Task Team to make recommendations on the regulation and formalization of the sector on the administrative, financial, and industrial relations levels. The planned reform included the legalization of the industry to tackle the oversupply of minibus-taxis through the registration of previously unregistered operators and the temporary prohibition of issuing new licenses. The financial formalization initiated through the Taxi Recapitalization Programme (TRP) aimed to curb the oversupply of minibuses while enhancing safety records by financially assisting owners to replace 16-seater minibus-taxis with newer 18-35 seaters. In order to qualify for the scheme, owners had to financially formalize, i.e register for taxation. While the program was successful as it managed to upgrade about 44,000 old vehicles in 2011, it was criticized for leading to a loss in jobs, increase in fare prices and creating demand for lower-fared “illegal” informal services. Lastly, the Industrial relations formalization aimed at the democratization of the sector as the government pushed for the formation of the National Taxi Council (SANTACO) to have a single industry representative body to carry out the negotiations. However, competition within the industry and power dynamics hindered it from becoming a truly representative body (Venter 2003). Yet, and despite these efforts, there were no visible improvements made to public transportation systems.

The Planning of Rea Vaya

Finally, South Africa’s hosting of the FIFA World Cup in 2010 acted as a necessary catalyst for improving public transportation and presented an opportunity to leverage funding to fast-track the planned investments (Schalekamp 2010). Therefore, in 2006 the National Department of Transport (NDot) launched a policy program to upgrade passenger transportation systems in the country. The Rapid Public Transport Network Programme aimed to renovate public transportation by implementing integrated BRT networks (Schalekamp et al. 2008). As the implementation of these networks would replace a significant portion of existing minibus routes, the policy specified the integration of informal operators in the new network. Nationally, 12 cities were included in the strategy to upgrade and integrate modes of public transportation, nine out of which were to host World Cup games. A supportive legislative framework was adapted to that end. NDoT’s Public Transport Strategy which was approved by the cabinet in 2007 encouraged capable municipal transport departments to implement, manage and regulate integrated quality networks with dedicated rights of way (MCCAUL and NTULI 2011). Additionally, NDoT prepared the National Land Transport Act which provides a framework for integrated transportation planning by the local authorities and included sections which enable BRT systems (Wilkinson 2010 and McCaul and Ntuli, 2011).

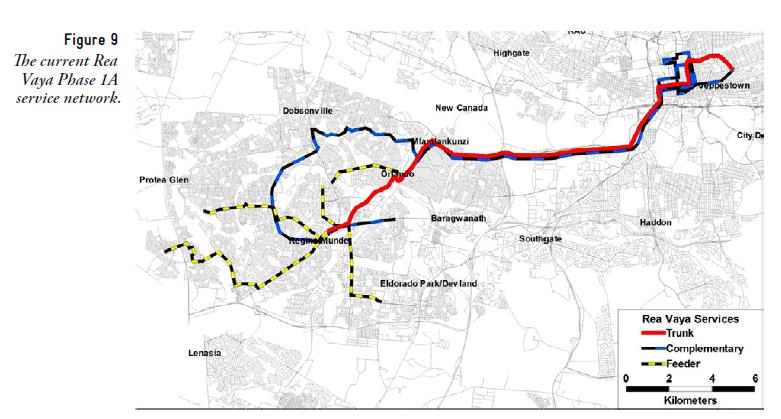

As such, the City of Johannesburg embarked on a mission to design and implement Africa’s first BRT system. Drawing lessons from the TransMilenio experience in Columbia, South African decision makers wanted to provide the system with a strong identity and brand image and have therefore given it the name of Rea Vaya meaning ‘We are going’ (Allen 2011). Phase 1A of Rea Vaya covered the busiest corridor of the city linking the city center to Soweto, the renowned densely-populated township. It consists of 27 stations and motorized and non-motorized feeder routes which serves neighborhoods and connects them to the main routes for BRT (Venter 2013). Construction of the roads and stations, as well as the transitional operating costs was funded primarily through the national Public Transport Infrastructure and Systems Grant (PTIS) given to the city by the central government (Allen 2011).

Implementation: Stakeholder Engagement and Negotiation Process

Planners of Rea Vaya were committed to engaging with minibus-taxi operators to reach an agreement that ensures the desired improvements in bus operations meet the demands of the informal operators. As expected, this proved to be a challenging process with this complex engagement taking place amidst opposition from operators not involved in the process who sometimes resorted to violence against those who were.

Prior to the formal negotiations, the city initiated months of engagement with bus and minibus-taxi operators potentially affected by the introduction of Rea Vaya. It was important to ensure their willingness to participate in any formal negotiations as the concept of formal bus service was contentious and had to be carefully presented. Initial discussions with the two largest taxi operators ‘Top Six Taxi Management’ and ‘Johannesburg Regional Taxi Council’ took place in 2006, followed by a study tour to Bogota, Colombia and Guayaquil, Ecuador. The city delegation was led by the Member of the Mayoral Committee of Transport and included the two operators, as well as two potentially affected bus companies, the privately-owned Putco and the city-owned Metrobus. The purpose of the visit was to showcase the concept of BRT to the bus and minibus-taxi operators and to enhance the municipality’s knowledge of system implementation possibilities in Johannesburg (McCaul and Ntuli 2011).

This was followed by the challenging task of identifying other potentially affected stakeholders. Upon the completion of this task, the 18 identified taxi associations were invited to form the Taxi Steering Committee (TSC) as a representative body to negotiate with the city. As per the request of TSC, the city agreed to pay for a technical expert to represent the committee’s interests and provided TSC with office space (McCauli and Ntuli 2011). Additionally, representatives from the 18 associations took part in a second visit to South America in 2007. Part of the engagement efforts included awareness-raising workshops and roadshows held by the city and the TSC to introduce the planned roll-out of the BRT to individual taxi association members and other operators on other affected and unaffected routes. This was done with the aim to persuade them to cooperate with the city rather than resist any engagement efforts which was the historical response to any changes in transportation sector reform (McCauli and Ntuli 2011 and Allen, 2011). These efforts culminated in a memorandum of agreement signed October 2007 where the two taxi umbrella bodies, Top Six Taxi Management and the Regional Taxi Council, confirmed their willingness and commitment to be involved in negotiations and identified the framework in which the negotiations will unfold. However, they withheld their full support for the Rea Vaya project until specific details become clear (Venter 2013).

In August 2008 the Phase 1A design was finalized. The priorities of the city and the TSC was to identify operators directly affected by the implementation of Rea Vaya and persuade them to agree on the process to be used in the negotiations to form a minibus-taxi-operators-owned bus operating company to operate the Rea Vaya. To that end TSC launched a registration process for the affected operators to indicate their interest in participation. Additionally, the city increased the resources it dedicated for technical, legal and financial advisers supporting the TSC. Additionally, it was agreed that negotiations will be facilitated by an independent mediator, who was jointly selected by the TSC and the city (McCauli and Ntuli 2011).

In August 2009 negotiations with the taxi representatives started and tackled many issues such as the process by which affected operators can become shareholders in the newly-formed operating company, as well as the compensation of drivers for the loss of income. The latter was expected due to the rollout of Rea Vaya services or the drivers’ inability to operate given the intimidation and harassment from other drivers as a result of their participation in the negotiations. Another issue discussed was the employment of displaced taxi drivers (McCauli and Ntuli 2011). Negotiations lasted for 14 months and included five framework agreements, such as the ‘Participation Framework Agreement’ that detailed the process of becoming a shareholder in the operating company and the qualifying documents.

Rea Vaya was launched on August 31, 2009 as scheduled prior to the end of the negotiations. Initially, BRT operations were run by a temporary bus operating company. A contract was finally signed on September 28, 2010, marking the end of the negotiation process (Venter 2013). Under the agreement, 313 taxi operators gave up their businesses and agreed to give up their 585 minibus-taxi vehicles for scrapping under the Taxi Recapitalization Program. The scrapping allowance they would receive upon turning in their old vehicles would be invested as working capital in the operators-owned operating company, PioTrans (McCauli and Ntuli 2011). In exchange the operators became co-owners or employees of PioTrans with the right to run route services for Rea Vaya. They signed a 12-year contract in which PioTrans is paid based on the distance travelled as set by the city rather than number of passengers carried. Under this agreement the city assumed all financial risk in case of low demand on the new service. By February 2011, the 313 minibus operators organized into 9 taxi operator investment companies to become shareholders in the new bus operating company PioTrans that was formed to replace the temporary operating company (Allen 2011).

Resistance to Rea Vaya

Despite the city’s efforts in reaching agreements, there have been moments of widespread and visible opposition to the rollout of Rea Vaya, in particular from unaffected minibus-taxi operators at the regional level who felt that those involved got a better deal. The months preceding the launch of Phase 1A saw multiple protests with minibus-taxi drivers blocking roads out of fear for their livelihoods. Given the experience drivers had with previous government schemes they were reluctant to believe government promises that legitimate jobs will not be compromised. A taxi association even went as far as to file a court application to stop the launch. However, the system was launched as scheduled. Protests took on a violent form as three days after the launch a gunman opened fire on a BRT bus leaving two injured. In response, the police went on a massive raid and buses and stations were guarded by police and army personnel for months following the incident (Venter 2013).

Results

The implementation of Rea Vaya has been considered a success on a number of levels. Importantly, by compensating the operators based on the distance travelled rather than the ridership, financial gains were decoupled from speeding and overloading to serve more customers. This dis-incentivized erratic driving behavior, making BRT a safer travel mode. Additionally, a passenger interview survey conducted in October 2010 showed that it also was a more desirable transportation mode, as the results indicated that Rea Vaya is attracting passengers who would have otherwise used private cars for reaching their destinations (McCauli and Ntuli, 2011).

From the operators’ point of view, the deal has made them better off as they have secured a 12-year contract and they have become shareholders of a modern BRT company. Loss of income has been a concern for the 585 displaced minibus-taxi drivers whose vehicles have been given up for scrapping. However, they have been offered chances to obtain employment with Rea Vaya, and 414 drivers were registered in the employment database in 2011, in addition to the 200 already employed by the temporary bus operating company as drivers (McCauli and Ntuli 2011). According to statistics, employment in Rea Vaya has secured the drivers significantly higher salaries with a combined increase in minibus-taxi drivers’ earnings of EUR 1.89m per year (ibid). Additionally, Phase 1A of Rea Vaya has created 6,800 permanent jobs, mostly in the construction phase of the project, in addition to 830 permanent positions (ibid). Lastly, the agreement has drawn together a number of historically-competing operators into one operating company fostering cooperation.

Conclusion

Rea Vaya was conceptualized to address historical inequalities and provide citizens with a fast, safe and reliable mode of transportation. Thanks to government subsidies fares for the new system are kept low, only 1R more than minibus taxis, to be affordable. When calculated, the benefits from safer road travel, faster travel time and decreased carbon emissions amounted to USD 980mn from the launch of Rea Vaya until 2015. Nonetheless, the implementation of BRT has been criticized by industry experts. The chief executive of the South African National Taxi Council (Santaco) claims that the minibus-taxi industry will remain to be the most accessible and used mode of private transportation with an estimated 15 million daily passengers. Others have noted that instead of implementing a new system the government should have focused on resolving the issues within the minibus-taxi industry.

If we look beyond the criticism pertaining to whether or not BRT should have been implemented to begin with, we will find that Egypt can draw two main lessons from the South African experience. Firstly, it has been remarkable in showing that a real transformation in public transportation systems – and reform in general – can only be achieved with a strong political will (McCauli and Ntuli 2011). In Johannesburg, city and national politicians have united in support of the reform and translated this will into supportive legislative frameworks which led to that end. This is not the case in Egypt where government plans and efforts remain uncoordinated.

Secondly, and more importantly, the City of Johannesburg demonstrated that a transformative change will not come about from a top down, regulatory approach but will only be achieved through a thorough stakeholder engagement that allows governments to identify the tools through which informal operators can be drawn to formalize (Venter 2013).

Transportation Economist Bongani Kupe who was part of the negotiation team between the city and the minibus-taxi industry noted that the insecurity that is associated with informality is not an incentive for informal operators to formalize, instead their ability to make profit in the new system is what drew them to participate in the project. A participatory decision-making progress was key to achieving results that benefit commuters and operators alike.

Works Cited

Allen, Heather. 2011. Africa’s First Full Rapid Bus System: the Rea Vaya Bus System in Johannesburg, Republic of South Africa. Nairobi: UN-Habitat.

https://use.metropolis.org/system/images/1518/original/GRHS.2013.Case_.Study_.Johannesburg.South_.Africa.pdf

Behrens, Rodger, Dorothy McCormick and David Mfinanga. 2016. Paratransit in African cities: operations, regulation and reform. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Cervero, Robert. 2000. Informal transport in the developing world (1st ed.). Nairobi: United Nations Centre for Human Settlements (Habitat).

McCaul, Colleen and Simphiwe Ntuli. 2011. Negotiating the Deal to Enable the First Rea Vaya Bus Operating Company: Agreements, Experiences and Lesson. Eschborn, Germany: Desutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ). https://www.sutp.org/files/contents/documents/resources/C_Case-Studies/GIZ_SUTP_CS_Negotiating-the-Deal-Rea-Vaya_EN.pdf

Salazar Ferro, Pablo. 2015. “The Challenge of Finding a Role for Paratransit Services in the Global South.” Paper presented at Energy, Climate, and Air Quality Challenges: The Role of Urban Transport Policies in Developing Countries, Istanbul, Turkey, February 2-5, 2015. http://www.codatu.org/wp-content/uploads/Pablo-Salazar-Ferro.pdf

Schalekamp, Herrie and Rodger Behrens. 2010. “Regulating Minibus-Taxis: A Critical Review of Progress and a Possible Way Forward.” In Proceedings of the 29th Southern African Transport Conference, Pretoria, South Africa. https://bit.ly/2teC8Bc

Venter, Christoffel. 2013. “The lurch towards formalisation: Lessons from the implementation of BRT in Johannesburg, South Africa.” Research In Transportation Economics, 39(1), 114-120. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2012.06.003

Wilkinson, Peter. 2008. “Formalising Paratransit Operations in African Cities: Constructing a Research Agenda.” Paper presented at the 27th Annual Southern African Transport Conference, Pretoria, South Africa, July 7-11, 2008.

Wilkinson, Peter. 2010. “Incorporating Informal Operations in Public Transport System Transformation: the Case of Cape Town, South Africa.” Brazilian Journal of Urban Management 2(1), p. 85-95. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/1931/193114459007.pdf

Woolf, S.E and J.W. Joubert. 2013. “A people-centred view on paratransit in South Africa.” Cities, 35, 284-293. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2013.04.005

الصورة الرئيسة من قبل: AfricanGoals2010

Featured Photo By: AfricanGoals2010

Comments