A User’s Guide to Habitat III: Its History, Challenges, and Ambitions

Next month, the Third United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Development will be held in Quito, Ecuador. Representatives from UN Member States and tens of thousands of dedicated urbanists are heading to the Ecuadorian capital with an ambitious mandate: to set a new agenda for the world’s rapidly urbanizing metropolitan areas. The UN-led global cities summit, referred to as Habitat III, comes at a time of historic levels of interest in sustainability and equity. The UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) adopted by all UN Member States in September 2015 and the COP-21 Paris Climate Agreement signed by 179 states three months later attest to a prevailing sense of urgency to ensure that cities grow inclusively, humanely, and sustainably. Habitat III’s organizers hope that this momentum will continue throughout the conference and conclude with an agreed-upon set of policies, principles, and commitments for wrestling the challenges facing cities in the 21st century.

Much has been said and written on Habitat III but throughout the flurry of dialogue on the conference’s ambitious goals and vision, it can be difficult to locate the opportunities for organizations and individuals outside of the UN apparatus to become more involved. For this reason, we hope this guide about Habitat III’s history, structure, planning, process, and avenues for engagement will help fellow urbanists, civil society advocates, NGOs, community groups, and citizens in Egypt and abroad make their voices heard at this momentous summit and in the policies and agendas that will follow.

The History of Habitat III: Vancouver and Istanbul

The UN global summit on cities and human settlements happens only once every 20 years. Habitat III is the third summit in the series, as its name suggests. The UN convened the first global cities summit in 1976, after rural-to-urban migration during the 1960s and early 70s precipitated an urban population boom which many governments, particularly in the developing world, were ill-equipped to face. Informal housing settlements, often characterized by inadequate living conditions and poor provision of basic services, quickly grew within metropolitan areas and nearby marginal expansions. A number of governments, unsure of how to cope with sudden, unplanned urbanization and the related issues of poverty and inequality, tried to expel residents from squatter settlements by force, yet this did not solve these problems (TADAMUN 2015).

The UN General Assembly gathered various member states and civil society organizations in Vancouver, Canada to kick-start a dialogue on best practices for tackling the challenges of rapid unplanned urbanization. This first conference produced the “Vancouver Declaration on Human Settlements” and also established the UN Centre for Human Settlements, which went on to become the UN Human Settlements Program, or UN-Habitat. The Declaration contained 74 recommendations for governments to adopt at the national level. It recognized that numerous human settlements around the world subjected residents to poor and increasingly deteriorating living conditions, without access to basic services or necessary infrastructure. It attributed these conditions to inequitable economic development, environmental, social, and economic challenges, demographic growth, deteriorating situations in rural areas, and involuntary migration due to political or economic conditions (TADAMUN 2015). Despite the Vancouver Declaration’s focus on the complex interplay of forces contributing to urban problems, the initiatives that governments adopted following the conference tended to approach urbanization from a purely technical standpoint. Governments across the globe, particularly in the developing world, focused their efforts on infrastructure, mega-projects, and the production of additional housing units, neglecting the prevailing social, political, economic, and historic context shaping the world’s changing cities (TADAMUN 2015).

Twenty years later in 1996, UN-Habitat convened the second UN cities summit in Istanbul, Turkey. Habitat II affirmed many of the takeaways from Habitat I, but added a few key developments. Whereas Habitat I was largely limited to UN member state representatives and select members of civil society, Habitat II expanded the base of the conference participants to include a number of local authorities and administrations, civil society organizations, academics, and private sector representatives. The conference produced the “Istanbul Declaration on Human Settlements,” or the “Habitat Agenda,” which adopted a focus on the issue of sustainable development and confirmed the provision of adequate housing for all as a goal. It suggested a number of strategies for addressing urban conditions, including: strategic planning, increased domestic/international financial investment, and strengthening of local government (UN-Habitat 2012). The Habitat Agenda also called for increased participation of community-based organizations, the private sector, professionals, and academics (UN-Habitat 2012).

Doubtless, progress has been made in some areas since Habitat II. Over 100 countries have adopted constitutional rights to adequate housing (Citiscope 2015) and global poverty levels have declined (UCLG N.d.). But whatever progress has been made over the past 20 years is overshadowed by daunting new challenges that have arisen. Most importantly, urban inequality has increased as cities house a growing share of the world’s poor (UCLG N.d.). According to the UN’s own estimates, nearly 1 billion people worldwide currently live in informal settlements without access to basic services such as sanitation and clean water (UN-Habitat 2012) and by 2050 the world’s urban population will nearly double (UN-Habitat III Secretariat 2016). Additionally, two-thirds of migrants moving from rural to urban areas in Africa are believed to be moving straight into informal settlements (UCLG N.d).

The Habitat II agenda has been criticized for of its scant attention to implementing, monitoring, and enforcing its stated goals and policy prescriptions. Following the second conference, the UN recommended that countries establish National Habitat Committees involving a wide range of stakeholders to collect and analyze data, assess programs, specify best practices, and compile this information into national reports (Cities Alliance 2015). Many countries did not establish such committees. Egypt established a National Habitat Committee in 2014, which will be further discussed in TADAMUN’s upcoming article in this series. Other organizations undertook efforts to satisfy monitoring needs “… but neither individually nor collectively allowed for a consistent monitoring of the Habitat Agenda across countries and over time. In addition, the review of progress on the Habitat Agenda has been deemed especially insufficient” (Cities Alliance 2015, 24). The Habitat II Agenda has also been criticized for promoting a “disembodied” view of the city—as a separate assemblage of parts rather than a whole unit. This fractured vision of urban areas precludes comprehensive and harmonious planning and development policies, coordinated both vertically and horizontally among government administrations. “The inherent limitations of this view are all too evident when one considers how overlapping and conflicting jurisdictions or local, regional, and national authorities result in weak urban governance and management. The results are plain to see; costly inefficiencies, poorly defined projects, unsustainable development—problems cities cannot afford, especially when undergoing rapid urbanization” (UN-Habitat 2012, 1).

Alongside these shortcomings, the authors of the Habitat II agenda failed to incorporate a key principle of sustainable and equitable urbanization into their vision for the world’s urban areas: the right to the city. The right to the city is defined as “the right of all inhabitants, present and future, permanent and temporary to use, occupy, and produce just, inclusive, and sustainable cities, defined as a common good essential to a full and decent life” (Global Platform for the Right to the City 2016b). It pertains less to an individual human right or any particular urban policy, and more to an ideal—an aspiration for the kinds of cities and towns we should try to achieve. It is an idea that places people at the center of the planning, building, and governing of human settlements, and a belief that cities belong to the people who live in them. It is the right of all citizens to utilize urban space to its fullest potential for living, working, or playing; the right of all people to have a say in envisioning and creating their city’s future to conform to their needs and aspirations. The principal components of the right to the city are: 1) spatially just resource distribution; 2) political agency; and 3) socio-cultural diversity (Global Platform for the Right to the City 2016b). For an in-depth overview of the right to the city, see the World Charter for the Right to the City from 2004.

‘Right to the city’ advocates argue that the new Urban Agenda must follow a human-rights approach with the right to the city as its cornerstone (Global Platform for the Right to the City 2016b). This approach prioritizes taking measures to overcome inequality, segregation, discrimination, and lack of opportunities. A New Urban Agenda grounded in the right to the city would democratize land management and institutionalize support for the social production of land (Pascual 2015). It would put into place mechanisms for participatory planning and budgeting, or enforce already existing mechanisms (Pascual 2015). The absence of the right to the city in a New Urban Agenda will contribute to the development of more urban policies that further concentrate wealth and power into a few hands, ignore the contributions that local communities make to the city, and result in urban areas characterized by poverty, exclusion, and environmental degradation (Pascual 2015).

Many of the advocates working today to include the right to the city in the New Urban Agenda are the same people who tried to do so unsuccessfully during the Habitat II process. They have encountered resistance once again this time around. The right to the city has been a source of tension in the Habitat III negotiations, so much so that it actually led to the breakdown of talks at the third Preparatory Committee meeting leading up to the conference. Fortunately, member state representatives and advocates emerged Saturday 10 September 2016 from a round of emergency negotiations and reached a consensus on the contentious issue.

Habitat III Structure and Process

Two main UN bodies are in charge of the Habitat III process and planning for the conference: the Habitat III Secretariat and the Habitat III Bureau. The Habitat III Secretariat is the official coordinating party. It prepares for major events like Preparatory Committees (PrepComs) and liaises with other UN agencies and civil society groups (Citiscope 2015b). The head of the Secretariat is Joan Clos, Executive Director of UN-Habitat. The Bureau is a group of 10 individuals representing 10 UN member states.1 This group acts in conjunction with the Habitat III Secretariat, and facilitates negotiations and plenaries at events like PrepComs (Citiscope 2015b).

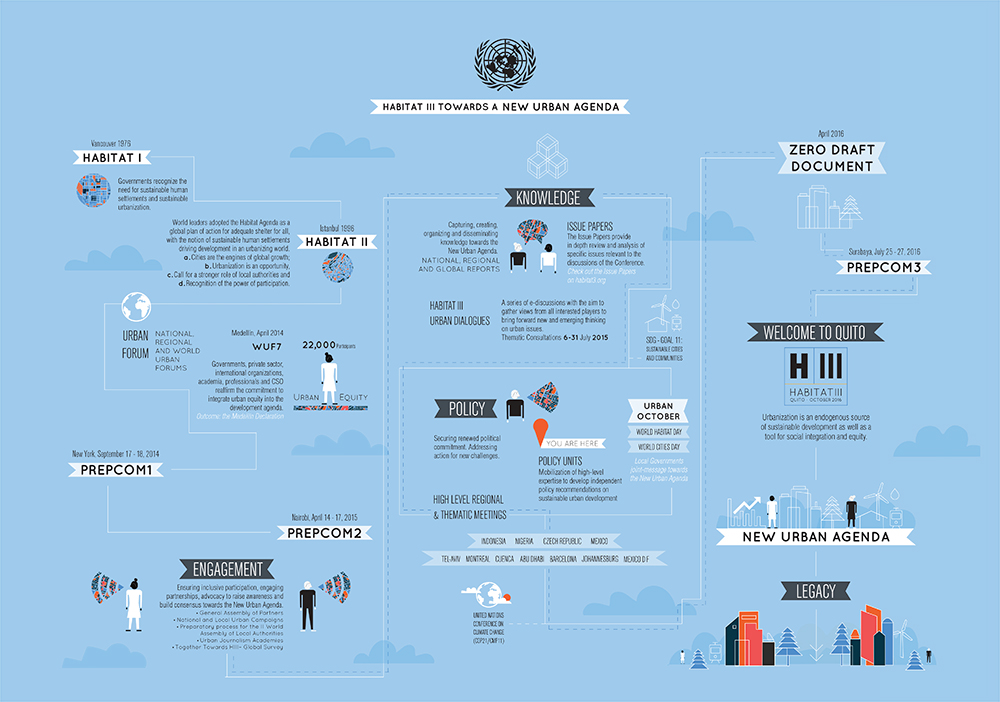

Habitat III Towards a New Urban Agenda (UN-Habitat, n.d.)

The preparation process for Habitat III began well over two years before the conference was set to convene. The main components of the Habitat III process included PrepComs, regional and thematic meetings, issue papers, policy units, and intersessional sessions (which brought together government representatives with civil society and others in a series of official meetings to consider the New Urban Agenda). UN-Habitat convened three major meetings of member state representatives called Preparatory Committees, or PrepComs, to plan for the conference. PrepCom 1 met in September 2014 at UN headquarters in New York and established national committees charged with preparing reports on urbanization and related issues in each member state. PrepCom 2 took place in Nairobi, Kenya, in April 2016 and defined the official dates and location of the Habitat III conference. At PrepCom 3, in Surabaya, Indonesia, in July 2016, delegates from 116 countries worked over three days of formal talks to reach a consensus on a draft of New Urban Agenda. The talks broke down over two contentious issues: whether to include a reference to the “right to the city” in the document and the future standing of UN-Habitat (Scruggs 2016).

UN member states hosted a total of 11 regional and thematic meetings between September 2015 and April 2016. These meetings were selected in response to proposals from member states and culminated in “final declarations,” which, according to Habit III, are considered “official inputs” in the Habitat process. Members of TADAMUN, participated in two side events at the Habitat III Thematic Meeting on Informal Settlements held in Pretoria, South Africa 7-8 April 2016 organized by the Agence Française de Développement (AFD) and the African Urban Research Initiative (AURI). These side events were a venue for civil society and professionals to discuss the manifestation of the discussed thematic issues alongside the formulation of the declarations by representatives of member states. The AFD panel focused on the improvement of the living conditions of informal settlement dwellers through promoting urban inclusion, knowledge production and recognition in policy, planning and legislation, with examples from Egypt and South Africa. Whereas the AURI panel discussed spatial inequality and aimed to bring policy makers into conversation with researchers from the AURI network to discuss recent work on the topic, its consequences and policy options in African cities.

The organizers of Habitat III solicited ‘expert’ input into the Habitat III process through issue papers and policy units. Development professionals from various UN agencies and the World Bank penned the brief issue papers covering the six thematic issues deemed most important for the Habitat process: 1) social cohesion and equity: livable cities; 2) urban frameworks; 3) spatial development; 4) urban economy; 5) urban ecology and environment; and 6) urban housing and basic services. The papers were submitted to the Habitat III Secretariat in May 2015 and became the basis for online thematic discussions open to stakeholders starting in July 2015. The issue papers were used to guide discussions among 10 policy units—groups of independent experts, who, following the discussions, provided formal input into the content and implementation of the New Urban Agenda. 2

Between April and July 2016, the UN convened 4 intersessional processes. These included three days of informal intergovernmental negotiations of UN member states in May, June, and July, and two days of hearings with local authorities’ associations and civil society stakeholders in May and June. During the hearings in May, local authorities representing cities from across the globe expressed discontent with their official status as mere “observers” of the Habitat III process (American Planning Association 2016). TADAMUN participated in the non-governmental stakeholder hearings during the June intersessional process, discussed in greater detail in the following section.

The first draft of the New Urban Agenda, known as the “Zero Draft,” was released in May 2016. The Habitat III Bureau and the Habitat III Secretariat were the ones to ultimately write the document. Subsequent political negotiations resulted in several iterations of the draft. After the breakdown in negotiations at PrepCom 3, the UN scheduled emergency negotiations for Friday 9 September. The talks were reportedly successful and, following 38 hours of non-stop negotiations, UN member state representatives reached a consensus (Scruggs 2016). The new draft of the New Urban Agenda is available here. This draft is likely to be adopted by states in Quito (Scruggs 2016).

Avenues for Civil Society Engagement in Habitat III

Participation in the actual conference in Quito is only open to individuals and organizations accredited by the Habitat III Secretariat. UN member state representatives receive accreditation through their national delegations. Civil society organizations may gain accreditation one of two ways: first, by being accredited to Habitat II in 1996 or to the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) and second, by applying for special accreditation. The deadline for special accreditation closed on May 1, 2016. Fortunately, attending the actual conference is not the only way to get involved.

The General Assembly of Partners

Non-governmental stakeholders can weigh-in on the Habitat III process and the New Urban Agenda by joining the General Assembly of Partners (GAP). The GAP is a sort of stakeholder umbrella group, administered by the Habitat III organizers to coordinate civil society input via 16 Partner Constituent Groups (PCG).3 The membership of each PCG consists of organizations—NGOs, grass-roots organizations, philanthropies, educational institutions, businesses—and individuals representing a specific sector or group, and two co-chairs, elected by the members. The co-chairs facilitate dialogue within their respective constituent groups on priorities for the content and direction of the New Urban Agenda through in-person meetings and virtual conferences. Members of PCGs may also communicate directly with their group chairs via email or over the phone, and send ideas and talking points to them for their meetings with the larger GAP general assembly. The specific protocol whereby PCGs coordinate member input is based on a voting system (a comprehensive description of the process is outlined in the General Assembly of Partners Constitution and By-Laws).

The PCG chairs, along with the president and vice president of the GAP have convened five times, most recently on October 2nd for the final time before attending the conference in Quito. Leading up to the conference, the GAP has been active in analyzing and commenting on the numerous iterations of the Zero Draft of the New Urban Agenda (as have many other, non-UN affiliated groups). Many of the PCGs have submitted official feedback to the various drafts of the New Urban Agenda, and these feedback documents are displayed on the official Habitat III website. The GAP also published an outcome document “Partnerships for the New Urban Agenda,” offering recommendations for “the implementation of the New Urban Agenda, role of multi-stakeholder partnerships in that process, and the mechanics of such partnerships” (General Assembly of Partners 2016). How exactly GAP input and feedback on the Habitat III process and outcome document is incorporated into official negotiations is not entirely clear, but constituent group chairs will be attending the conference in Quito and the official conference program includes various assemblies and roundtables for each PCG.

Organizations and individuals may register and join the GAP through the constituent group with which they identify. Membership is open to all stakeholders (groups and individuals) with an interest in sustainable urbanization. To access the GAP registration system, please click here. For more information on individual PCGs and the contact information of the co-chairs, please click here here.

Habitat III National Committees

Organizations and individuals who are citizens of countries actively engaged in the Habitat III official negotiations may also be able to participate or weigh-in directly with their countries’ national delegations. However, individual member states are in charge of selecting members for their countries’ national committees. Accordingly, avenues of participation for civil society and individuals through national Habitat III committees will vary country to country. For example, the US Department of State and Department of Housing and Urban Development are taking a leading role in the United States Habitat III Committee, but the committee is comprised of over 40 organizations representing federal government agencies, regional and local governments, as well as civil society, academia, philanthropy, and the private sector. In countries where public participation in government is quite low, national Habitat III delegations may also be less inclusive. With no established guidelines from the UN regarding the composition or process for national Habitat III committees or national reports, member states face little to no pressure to form diverse and pluralistic national delegations.

The Urban Thinkers Campus Initiative

The World Urban Campaign (WUC), an initiative coordinated by UN-Habitat, convened a series of 16 “Urban Thinkers Campuses” between June 2015 and February 2016, designed to gather broad stakeholder input from non-governmental organizations and individuals.4 The Urban Thinkers Campuses consisted of meetings with 12 constituent groups, whose input WUC incorporated into an outcome document, The City We Need 2.0 . This document contributed to the Habitat III negotiations, but, again, it is not clear precisely how its recommendations were incorporated into the New Urban Agenda drafting and negotiations process.

Civil Society-led Initiatives

NGOs, philanthropies, academia, community groups, activists, and others with an interest in sustainable urbanization are making use of the buzz Habitat III has generated to engage around issues of sustainability, equality, and urbanization in a wide variety of ways. Members of TADAMUN, for example, participated in a panel discussion on the New Urban Agenda in Western Asia hosted by the Ford Foundation in collaboration with the Habitat III Secretariat 16 June 2016. This panel brought together development professionals, scholars, and urbanists from Egypt, Lebanon, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates to discuss key considerations and concerns for the New Urban Agenda in cities in the Middle East and North Africa. Panelists drew on their own experiences to share insights on the challenges that weak or inefficient government poses to the implementation of sustainable and just urban policies; the urgent need to equip urban residents with the tools and resources they need to be resilient to the damaging effects of climate change; the underlying social, political, and economic drivers of urban inequality; the often unjust and inequitable distribution of public goods, resources, and services in cities like Cairo; among other topics of paramount importance to urban dwellers throughout the region. This panel discussion was part of a larger series of urban breakfasts held by the Habitat III Secretariat to address key priorities to take account in the New Urban Agenda. The Ford Foundation hosted a number of these breakfast panels, including one every morning during the week of June 6 to coincide with the UN-Habitat civil society intersessional process that week. TADAMUN also participated in an urban breakfast that week co-hosted by the Ford Foundation and the UN Major Group for Children and Youth.

Others with an interest in the New Urban Agenda have joined forces around specific debates in the Habitat III process. As we already mentioned, the right to the city has arisen as a point of controversy in Habitat III talks. To advocate the right to the city as a central component in emerging development policies at all levels, over 100 organizations from all over the world came together under the banner of the Global Platform for the Right to the City (GPR2C). In the year leading up to Habitat III, the GPR2C has been working steadily with its member organizations to promote dialogue on the inclusion of a comprehensive right to the city in the New Urban Agenda. In May 2015, GPR2C sent this letter to Ana Moreno, Habitat III Secretariat Coordinator suggesting a list of experts for the Habitat III process policy units. Members of the group also attended the Second Latin American and Caribbean Forum on Adequate Housing, where they engaged a number of high-level housing and urban development government officials as well as local government officials on topics such as security of tenure, affordable housing, access to urban land (Global Platform for the Right to the City 2016). The event concluded with a set of recommendations for the New Urban Agenda contents including guiding principles and key actions for national and local policy (Global Platform for the Right to the City 2016).

In addition to participating in events, GPR2C launched a media campaign promoting the right to the city. They are active on Facebook and Twitter, and launched an online petition, Global Call for the Inclusion of the Right to the City in the New Urban Agenda. They even produced a short documentary on YouTube titled “Two Worlds, One City,” which follows the lives of two women living in the same city to highlight the disparity in access to and quality of public space that characterizes their lived experiences.

GPR2C also coordinated efforts for their member organizations to participate in UN-Habitat’s various online stakeholder participation platforms—encouraging them to nominate experts for the policy units and contribute to the Urban Thinkers Campus virtual sessions. They publicized and promoted a statement released by a coalition of Brazilian civil society organizations, many of whom are members of GPR2C, on the content of the Zero Draft of the New Urban Agenda. The statement offers a series of pointed critiques on the Zero Draft’s consideration of the right to the city and its related topics, including its approach to the treatment of marginalized citizens, silence on the social function of property, and absence of implementable mechanisms for transparency and democratic urban management. TADAMUN translated this statement into Arabic and it can be found here.

Final Thoughts

Habitat III and the forthcoming New Urban Agenda is all about cities and towns—human settlements at the local level. But, as is clear from much of the information in this brief, UN member states are the principal players in the Habitat III process. The conference organizers have facilitated significant non-governmental stakeholder and local government administrations engagement processes, but ultimately the Habitat III Secretariat and Bureau are responsible for writing the New Urban Agenda. At the conference, member state representatives will be the ones voting in the negotiations, and the potential success of the New Urban Agenda depends directly on member state buy-in.

But that is not to say that everyone with a stake in the Habitat III process is at the mercy of national governments and their voting power. In early September, the General Assembly reached a consensus and agreed to include the right to the city into the Zero Draft of the New Urban Agenda. The New Urban Agenda was never conceived as a binding charter, but it is being developed at the same time as other international efforts with more authority over their signatories. UN Member States have already signed on to the Paris Climate Agreement and the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals which share some of the important priorities of the Habitat III’s New Urban Agenda. The most obvious policy convergence is SDG Goal 11: to make cities and human settlement inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable. Habitat III is widely referred to as the first implementation conference on the 2030 development agenda and its shared objectives with the SDGs, for example, may be called upon to encourage earnest commitments on the part of national governments. Together, these three global processes my complement each other, reinforce their commonalities, and move the international community towards a more sustainable, just, and equitable future.

Whatever the outcome of Habitat III, the New Urban Agenda will have an impact on orienting the UN, donor organizations, official development assistance, and various governments in their treatment of urban areas in the coming decades. Any new urban development paradigm designed to take on urban challenges with their increasing complexity must recognize that cities can be a source of enormous good for the world where residents can live with dignity, security, equality, and hope.

Habitat III will need to focus far more on member state implementation and accountability to avoid the shortcomings of the previous conference in Istanbul and deepen sustainable and equitable urban development after everyone returns home from Quito. The priorities of the New Urban Agenda need to become ‘normalized’ and commonly accepted policy and it will take civil society and a range of governmental and non-governmental actors to forge that path. TADAMUN will participate in some of the proceedings in Quito and we plan to address these issues as well as Egypt’s role in Habitat III and implementing the New Urban Agenda in forthcoming briefs. Stay tuned.

Works cited

American Planning Association (2016). “The Road to Habitat III.” Series of Online Updates on the Habitat III process. N.d. Accessed 2 September, 2016.

Cities Alliance (2015). “Sustainable Development Goals and Habitat III: Opportunities for a Successful New Urban Agenda.” Discussion Paper #3. November. Accessed 5 September, 2016.

Citiscope (2015b). “Who are the Habitat III Major Players?” Informational piece in Citiscope’s Toward Habitat III series. N.d. Accessed 2 September, 2016.

Citiscope (2015c). “What is the New Urban Agenda?” Informational piece in Citiscope’s Toward Habitat III series. N.d. Accessed 2 September, 2016.

General Assembly of Partners (2016). “Partnerships for The New Urban Agenda.” A Position Paper of the GAP towards Habitat III. May. Accessed 2 September, 2016.

Global Platform for the Right to the City (2016a). “UN Receives Online Suggestions for Habitat III until Friday (31).” Online statement. N.d. Accessed 3 September, 2016.

Global Platform for the Right to the City (2016b). “What’s the Right to the City? Inputs for the New Urban Agenda.” Informational Packet on the Right to the City. N.d. Accessed 30 August 2016.

Pascual, Isabel (2015). “A Needed Cornerstone for Habitat III: The Right to the City.” Citiscope. 15 February. Accessed 2 September, 2016.

Scruggs, Greg (2016). “Final Burst of Talks Results in Consensus on Draft New Urban Agenda.” Citiscope. 11 September. Accessed 11 September, 2016.

Scruggs, Greg (2016b). “For the New Urban Agenda, It’s Now or Never.” Citiscope. 7 September. Accessed 8 September, 2016.

TADAMUN (2015). “The First Egyptian Urban Forum: Is There Anything New?” 16 June.

UN-Habitat (2012). “Habitat III Partners Consultation Paper #1.” UCLG.org. 10 July. Accessed 6 September 2016.

UN-Habitat (1996). “Report of the United Nations Conference on Human Settlements (Habitat II).” 7 August. Accessed 7 September 2016.

UN-Habitat (1976). “The Vancouver Declaration on Human Settlements.” June. Accessed 7 September 2016.

World Urban Campaign (2016). “The City We Need: Towards a New Urban Paradigm.” UN-Habitat. N.d. Accessed 5 September, 2016.

1. The 10 member states, selected for geographic balance are: 1) Chad, 2) Chile, 3) Czech Republic, 4) Ecuador, 5) France, 6) Germany, 7) Indonesia, 8) Senegal, 9) Slovakia, and 10) the United Arab Emirates.

2. The policy units include: 1) the right to the city and cities for all; 2) socio-cultural urban framework; 3) national urban policies; 4) urban governance, capacity, and institutional development; 5) municipal finance and local fiscal systems; 6) urban spatial strategies: land market and segregation; 7) urban economic development strategies; 8) urban ecology and resilience; 9) urban services and technology; and 10) housing policies.

3. The Partner Constituent Groups include: 1) local and sub-national authorities; 2) research and academia; 3) civil society organizations; 4) grass roots organizations; 5) women; 6) parliamentarians; 7) children and youth; 8) business and industries; 9) foundations and philanthropies; 10) professionals; 11) trade unions and workers; 12) farmers; 13) indigenous people; 14) media; 15) older persons; and 16) persons with disabilities.

4. The World Urban Campaign (WUC) is an advocacy and partnership platform coordinated by UN-Habitat. Its stated objective is to “raise awareness about positive urban change in order to achieve green, productive, safe, healthy, inclusive, and well planned cities.” 136 organization comprise the WUC, including partners such as Oxfam, United Cities and Local Governments, Cities Alliance, Communitas, and Habitat for Humanity. It is a part of UN-Habitat’s work program and acts as an advisory body to UN-Habitat’s Executive Director.

Featured image Source: UN-Habitat Official Website

Comments