A User’s Guide to Habitat III: A Reading of Egyptian Urbanism from the Perspective of the Habitat Agendas

A User’s Guide for the Third United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Development (Habitat III).

An Egyptian citizen does not need to obtain an entry visa to travel to Quito, the capital of Ecuador, where the Third United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Development or (Habitat III) was held from the 17th – 20th of October. This conference witnessed the adoption of the New Urban Agenda by the Member States. This non-binding agenda sets out a vision for cities, or what the participating countries hope that cities will be like in 2030. It is a vision of cities that have overcome poverty and inequality, where an individual enjoys a decent life and adequate housing as his inalienable rights, without any discrimination on the grounds of gender, race, religion, or social class, and within a framework of an inclusive and growing economy in a sustainable environment (UN, 2016).

This New Urban Agenda is considered the second of its kind after the UN inaugurated “the 1996 Habitat Agenda” as a reference document for urban development. Within the context of the New Urban Agenda, the Egyptian government and some civil society organizations concerned with Egyptian urbanism are endeavoring to address the Agenda in light of local changes, as well as regional and global variables. Therefore, TADAMUN aims in this article to shed light on Egyptian urbanism, through an examination of urban policies and legislations to better understand the extent of the influence of the 1996 Habitat Agenda on its development. Then, we will reflect on the implications of the New Urban Agenda on future urban policies and strategies in Egypt, and their impact on the urban reality experienced by its citizens.

Forty Years Ago

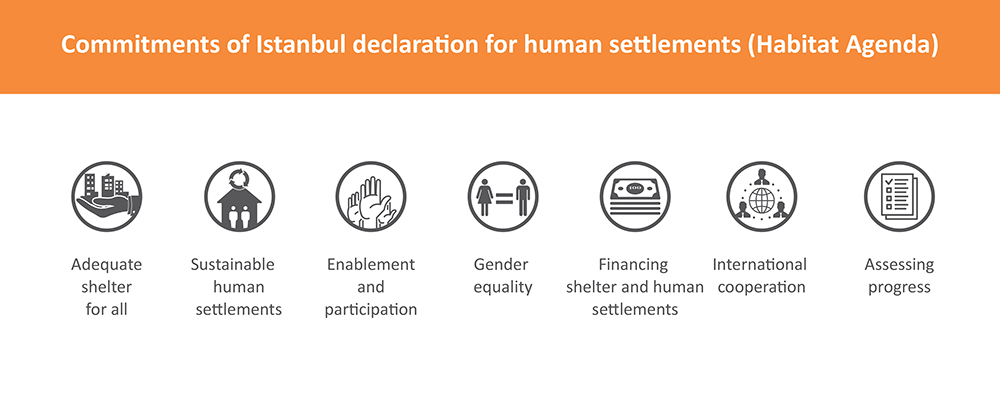

The story of Habitat conferences started in Vancouver in Canada in 1976, when the first United Nations Conference on Human Settlements “Habitat I” was held. The conference issued the Vancouver Declaration on Human Settlements, which clarified the urban challenges that were facing the international community. These challenges were: “the inequitable economic growth; social, economic ecological and environmental deterioration; World population growth; uncontrolled urbanization; rural backwardness and dispersion; and international involuntary migration.” The Declaration put forth an action plan that included several axes to confront these challenges, which were: development policies and strategies; urban planning; shelter, infrastructure and services; land; public participation; institutions and management (United Nations Habitat, 1976). The outcomes of the first conference included establishing the UN-Habitat program in 1977, and it was decided to hold Habitat Conferences once every twenty years (United Nations Habitat, 2012). In 1996, Habitat II was held in Istanbul, Turkey and the Istanbul Declaration on Human Settlements was issued, or what is commonly known as “The Habitat Agenda”, in order to cope with the development of urban challenges and their increasing complexity. The Agenda contained seven key commitments, which included: adequate shelter for all; sustainable human settlements; enablement and participation; gender equality; financing shelter and human settlements; international cooperation; and assessing progress (United Nations Habitat, 1996).1 In 2001, the United Nations General Assembly invited member states that participated in the first – and last – special session conducted to monitor and evaluate the implementation of the Habitat Agenda.

Egypt and the Habitat Agenda

Egypt ratified, as a member of the Group of 77 and China, the Vancouver and Istanbul declarations.2 In parallel, the urban policies and strategies in Egypt have been developing over the last several decades. In view of the non-binding nature of the Habitat Agendas, we will review the previous commitments to determine where the urban policies and practices in Egypt stand with respect to the Habitat Agenda, analyze if the Agenda has had an impact on Egyptian urbanism, and assess the extent to which Egypt has succeeded in confronting local challenges related to these commitments.

Firstly, we cannot properly evaluate the Egyptian situation from the perspective of each commitment separately because the commitments are all interconnected. In doing this, we risk losing connections that are necessary in clarifying the role of the agenda as a global charter in impacting Egyptian urbanism. However, we will review what has become of the urban reality in Egypt at the present time, and understand whether or not the urban agenda has had an effect on it and what, if any, is this effect.

Egyptian Legislation

Egyptian legislation witnessed important changes in the last decade. Egypt went through two constitutional changes after 2011, through which the constitution went through relatively positive developments regarding public rights, freedoms and duties, where Articles 68 and 78 respectively recognize the right to access information and the right to adequate housing for the first time. In the 2014 constitution, Article 63 prohibits arbitrary forced displacement of citizens, in addition to the inclusion of a paragraph in Article 78 focusing on the informal settlements.3 It can be said that these amendments were not a direct outcome of the Habitat Agenda, which called for adequate shelter for everyone, as these amendments were made 18 years after the 1996 Habitat Agenda. Most notably, the article relating to the right to adequate housing was added to the Egyptian Constitution after the topic was raised by one of those concerned with issues of urbanism in the committee for preparing the constitution; in other words, it was the result of the effect of the urbanism movement in Egypt after 2011. However it is worth mentioning that these constitutional articles have yet to be translated into laws that can be implemented. Prior to that, the Unified Building Law No. (119/2008) was issued, where sustainable urban development was introduced and defined in its second article, stating that achieving it is the main goal of the development of strategic plans at various levels. It is possible to think that the article is related to the second commitment of the Agenda concerned with providing sustainable human settlements, but we have to bear in mind that this law – similar to the Constitutional articles above – came 12 years after the launch of the Habitat Agenda, and after the term “sustainable development” had become prevalent worldwide.

It may seem that the Habitat Agenda does have an impact on the formulation of Egyptian legislation concerned with physical planning, but the time gap between the issuance of the Agenda and these legislations brings the question whether that effect was due to the direct adoption of the Agenda by the government, or due to the spreading of the concepts and terms of the Agenda on the world stage, which imposed the adoption on the government in order to keep up with the global change. The answer to this question is related to the extent to which these legislations are translated into policies and strategies and their actual implementation. In the next section we will review the extent to which sustainable urban development was achieved, the provision of adequate housing, and the focus on informal settlements, and to what extent the empowerment and participation mentioned in the commitments of the Habitat Agenda has been achieved.

Urban Policies and Strategies

The second article of the Unified Building Law No. (119/2008) defined sustainable urban development as “managing urban development through optimal exploitation of the available natural resources, so as to satisfy the requirements of the current generations, without compromising the opportunities of future generations.” But the policies of the state do not reflect that it is striving to achieve sustainable urban development to date. The national development policy in Egypt in the past decades was significantly targeting cities, resulting in a noticeable development lag in villages and rural areas. Cities receive the greater share of financial resources, while rural areas were not similarly privileged and national development programs significantly deprived rural areas of the central administration’s limited resources. This is a result of their inferior political power in the hierarchy of the local administration. As such, human settlements have not seen the comprehensive development that was recommended by the Habitat Agenda in 1996. However, the state launched in 2007 – 11 years after the issuance of the agenda – a national program for the development of the most deprived villages, funded by local and international donors.

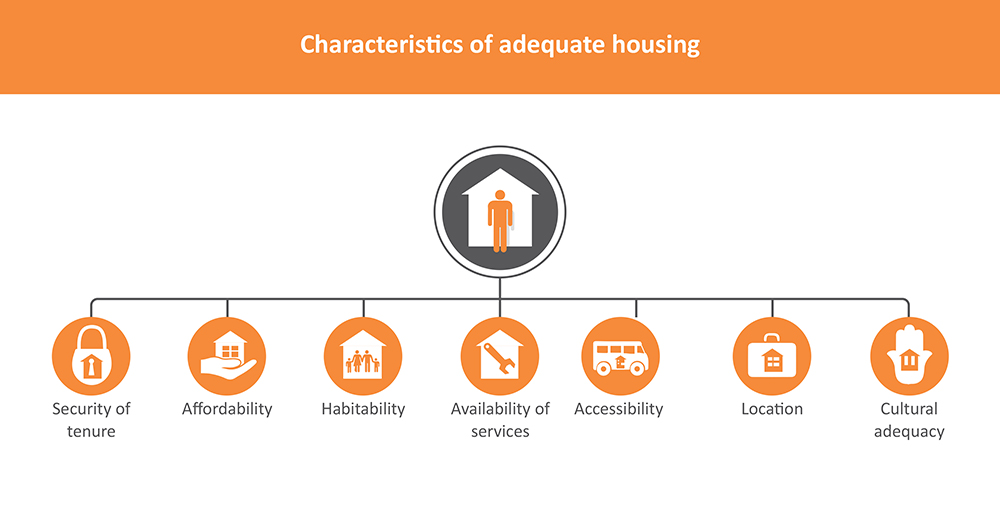

When we focus on urban development, we find that there is also great disparity between Cairo and other governorates – and even between the various districts in Cairo – whereby Cairo gets a large percentage of the development allocations because of the centralized nature of the state and centralized planning. This is the centralization which the Habitat Agenda called for its reversal to ensure a balanced development between the different regions, and equity in the distribution of public resources.4 This centralization also led to the mismanagement of land, for instead of it being used to satisfy the needs of the present and future generations for housing, it was used to maximize the profits and revenues of the State. The practice of building new urban communities in the desert, which has been official state policy for several decades and led by the New Urban Communities Authority, illustrates how poor this policy has been.5 It has been criticized by current officials in the Egyptian government, such as Deputy Minister of Housing (Dr. Ahmed Darwish) as well as the current coordinator of the International Alliance for Habitat in Egypt (Joseph Shaklah). The mismanagement of land in Egypt stems primarily from the philosophy of “land is a financial resource”. In other words, this philosophy rests on exploiting the most abundant resource in Egypt – namely the land – as a means to finance the budget deficit and to increase public resources. On the other hand, the urban development strategy adopted in Egypt generally, and in new cities in particular, depends on the philosophy of “modern housing”, where the State assumes that providing housing units built using the most modern building materials is sufficient to provide adequate housing, as is mentioned in the Arab Republic of Egypt National Report in 2016. This is also in contradiction to the concept of adequate housing adopted by Habitat Agenda and agreed upon internationally in the Universal Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. According to the modern literature on urbanism, the individual should be the focus of development, the provision of adequate housing is more than just housing units, and land has a social function for the community as a whole, and particularly for those with the greatest need (Habitat International Coalition – Housing and Land Rights Network, 2016).

Characteristics of adequate housing according to the United Nations – High Commissioner for Human Rights (Graphics: TADAMUN Initiative)

As for the urbanism of existing cities, the policy followed is that of detailed strategic development plans, which are prepared by the General Organization for Physical Planning. Those plans are supposed to reflect the needs of the inhabitants and try to use the available resources to satisfy them, but the preparation process is not carried out through public participation as recommended by the Habitat Agenda in the enablement and participation procedure. According to Article 14 of the Unified Building Law (119/2008), citizens, civil society representatives other parties who are all development partners should be invited during the process of preparation of the plan through advertising in two widely read newspapers and organizing public hearings. However, the code does not mandate the approval of the citizens or the civil society of the plan. The approval of the Local Popular Council only (the only elected form of local governance in Egypt, residents elect members of the council for their municipality, but they have been defunct since 2012) is sufficient. These hearings essentially depend on the will of the decision makers to listen to the citizens and to take their opinions and comments into consideration. Some hearings have the sole aim of informing the citizens of the decisions that have already been taken by the officials, while others are for discussion, where all parties exchange their opinions and suggestions. But, at the end of the day, the results of those hearings are non-binding to the decision makers. Finally there are hearings that are characterized by debates and voting for a particular decision that is reached during the hearings and the decision is usually binding to the executive authorities. However, the actual experience of such hearings in practice indicate that many of them do not result in the actual integration of the citizens and the community in the urban planning process. Many of them turn into a sham process solely aiming to satisfy one of the requirements for plan preparation. For example, a survey of a random sample regarding the hearing held in the town of Ghanayem in Assiut showed that only about 10% of the respondents were aware that a strategic plan for their town was being prepared, and that only about 7% of the respondents were aware of the hearing.6

As for the informal settlements in existing cities, these were dealt with reactively. Before the Habitat Agenda for the year 1996 was issued, in 1993 the State launched a national program for the development of informal settlements as a reaction to the displacement of people from their homes which had collapsed due to the 1992 Cairo earthquake, and to the spread of Islamic movements in Imbaba, Giza.

Then once again in 2008, the State reacted to another incident in a Cairo informal area, the rockslide in Al-Duwiqa neighbourhood in Manshiyyat Nāṣir. In reaction to this disaster, the Egyptian state established the Informal Settlements Development Facility (ISDF) in the same year in order to “identify the slum areas, develop them, establish the necessary design for their urban planning, and provide them with basic facilities, such as water and sanitation and electricity” (ISDF, 2008). Through the ISDF, informal settlements country-wide were classified into unsafe areas and unplanned areas, this classification still holds today, and informal settlements are dealt with in accordance to it. We can also say that placing informal settlements on the list of priorities of the government was not due to the effect of the Habitat Agenda, but came as a response to local changes happening to the Egyptian urbanity. Currently the ISDF follows the approach of “Human-centered Development”, where the Egyptian citizen takes priority in development. This started during the time of the Ministry of State for Urban Renewal and Informal Settlements, which lasted for one year only (2014 to 2015). This approach was very evident in the way the ministry – and currently the ISDF –dealt with the issue of the Maspero Triangle, where the minister at that time – Dr. Laila Iskandar – met with the people and civil society on more than one occasion to discuss the development of the area. However, obstacles concerning the mechanisms of funding and legal forms of tenure stand in the way of moving forward in the implementation of that project which the ISDF considers one of the most successful projects for the development of informal settlements.

On a different note, the Egyptian government has launched a Sustainable Development Strategy: Egypt Vision 2030 (SDS) after the universal Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) had been announced, which makes us wonder whether the Egyptian government is now keeping up with global documents. However, the Egypt Vision 2030 did not include any mechanisms for the implementation of the strategy, and none has been prepared so far. The TADAMUN Initiative has analyzed the SDS and its position regarding the United Nations SDGs in a series of articles – which are available here.

Development Projects

Development projects can be considered the application of urban policies and strategies on the ground. Urban development projects in Egypt are divided into housing and infrastructure projects, projects that support local urban policies and local administration, and others for the development of informal settlements. The State established social housing projects in new and existing cities. However, most of these projects, as we mentioned earlier, have not achieved adequate housing for citizens. The State tried to improve some of the services rendered to citizens within the existing cities through local development programs, but the limited financial resources allocated to local authorities – which did not exceed 12% of the State expenditure in 2011/2012 – hindered the desired development.7 This was due to the centrality of the urban administration, which once again conflicted with the Habitat Agenda, as state expenditure on the local administrations is usually in the range of 20-40% of their public resources. The projects that support local urban policies and local administration were carried out through cooperation between the Egyptian government and UN-Habitat and the German Technical Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ) in particular. Examples of such projects are the Participatory Development Program in Urban Areas (PDP) and the establishment of urban upgrading units within the governorates, with financial and technical support from the GIZ as well as the project of Strategic Urban Planning for Small Cities in collaboration with UN-Habitat. Such projects, in their abstract framework, can be considered a direct outcome of the Habitat Agenda, particularly in terms of the Agenda’s recommendation to increase international cooperation. But on the other hand, there are significant shortcomings in the local administration which impede the achievement of sustainable development. For example, the Urban Upgrading Unit was established in Cairo Governorate in 2007, with the financial and technical support of the GIZ, which also assisted in the capacity building of its staff. But, several years later, when the Agency started re-assessing this Unit, it was discovered that its role within the governorate was not clear, in addition to obstacles in communicating with other departments within the governorate. The goal here is not to minimize the merit of the Unit, but to point out that international cooperation is not “Aladdin’s lamp”, for even if the international parties follow global agendas this does not necessarily mean that the values of those agendas have been achieved on the ground.

The projects for the development of informal settlements in Egypt was and remains linked to a handful of successful experiments, that have not been adopted at the national level, rather than linked to global agendas and conventions. Al-Salam district in Al- Ismailia in 1979, was developed based on the model of “Site and Services” with funding from the US Agency for International Development (USAID) (Clifford Culpin and Partners, 1983).8 Masakin Zinhum area was developed with funding from the Egyptian government based on the model of (in-situ development)) and several projects for the development of informal settlements had been carried out during the past four decades.9 However, the decisive point is not the number of projects, but the extent to which the conditions of ordinary citizens living in those areas had improved. We cannot answer this question with any degree of certainty, as the follow-up studies and evaluation of projects are not performed as required, and this also goes against the Habitat Agenda.

Urban Movements in Egypt

From another perspective of the State’s activities, the urban movements in Egypt developed from being just a human rights movement concerned mainly with the issues of forced evictions to a more integrated form (what we mean by urban movements is the local initiatives concerned with urban issues that arose from the civil society). A new urban movement appeared in Egypt – since 2011 – that is trying to reform the State’s methodology in dealing with Egyptian physical planning. This movement works both theoretically and practically in parallel at the local level which the State is unable to deal with or cannot perceive. Several initiatives specialized in Egyptian physical planning have emerged, some of them investigate the problems of urbanization theoretically, criticize the State’s policies in dealing with them, and offer theoretical solutions to those problems, such as 10 Tooba: Applied Research on the Built Environment and TADAMUN: Cairo Urban Solidarity Initiative. Others actually implement urban interventions, such as Megawra: Built Environment Collective, Cairo Lab for Urban Studies, Training and Environmental Research (Cluster) and Takween Integrated Community Development. A percentage of these urban movements have had an impact on the formulation of articles of the constitution, which were previously mentioned in A Constitutional Approach to Urban Egypt, in cooperation with human rights organizations, such as the Land and Housing Rights Network, the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, the Egyptian Center for Civil and Legislative Reform and the Egyptian Center for Economic and Social Rights. These movements also played a role in the negotiations for the development of Maspero triangle, such as the Madd Platform, which is the organization that presented an alternative report to the United Nations’ Universal Periodic Review in 2014. These movements also contributed in providing some services in informal settlements such as Manshiyyat Nāṣir, Izbit Khairallah and others.10

These movements arose through the efforts of urban practitioners who had acquired theoretical and practical knowledge through their exposure to developmental experiences in various countries, and who tried to bring that knowledge to the Egyptian urbanity. These practitioners had gained the theoretical knowledge by studying international literature on urbanization, especially since sociology and urban economy are not taught in Egyptian Universities specializing in urbanity at the undergraduate stages in a manner that allows the development of the understanding of the urban system in its comprehensive framework. As for the practical knowledge, the practitioners acquired it through their exposure to global experiences or through their implementation of international urban literature by adapting it to suit Egyptian urbanism. In most cases, this urban movement is financially supported by local and international donors, which often follow international conventions, including the 1996 Habitat Agenda. However, we could not find a comment or critique of the agenda by the urban movement in Egypt, except the articles published by the Habitat International Coalition in Egypt to comment on the importance of the agenda for Egypt, and where Egypt stands vis-a-vis that agenda. Of course we cannot say for sure that the Agenda has no impact whatsoever on the urban movement, but we find that the Habitat Agenda did not have a key or direct role in the emergence of this movement. However, we can understand the relationship between the urban movement and the Agenda through the international literature concerning urbanism. We can say that the principles and commitments of the Agenda were what all development partners unanimously agreed upon in the contentions on urban literature. The philosophy of the Agenda becomes apparent here in its being a benchmark to guide the orientations of different parties and a document to monitor their activities, without disregarding the fact that it is non-binding. Through this philosophy we can also understand the impact of the Agenda on the financial support of the urban movement. The benchmark for donors is often based on those agendas that, although non-binding, cannot be breached overtly, but the main drive is their own ideologies and policies. We find, for example, that the GIZ supports participatory development programs and local administration in particular. Here we find another important factor that affects the urban movement in Egypt which is international financial support, which may or may not be linked to global agendas. Many of the global hot issues or issues of priority, such as, for example, inequality and refugee issues are reflected in the international agendas of donor agencies, and certainly impact the directions in which financial grants are directed. So, we can say that the Agenda is one of several factors that affect the financial support given to the urban movement in Egypt, but we cannot state with any certainty the extent of the influence of such factors specifically.

Egypt Travels to Quito

The international conventions, such as “The New Urban Agenda” – although they are non-binding – continue to possess the glamor that makes the Egyptian government and civil society keen on participating in the events of Habitat III, each for his own reasons. But the United Nations placed conditions on the participation of Member States, the most important of which was preparing the “Arab Republic of Egypt National Report”, published in English only. This report included the Egyptian urban challenges for the New Urban Agenda, which include challenges relating to the demographics, urban planning and land, the environment and urbanization, governance and urban legislation, the urban economy, and finally to housing and basic services. The other requirement was the formation of a National Habitat Committee, to strengthen the communication between key partners on the national level. The National Report mentioned that the committee was formed by the decree of the Minister of Housing No. 33, year 2014; a number of ministries and other development partners were represented to review the National Report.11 However, the Habitat International Coalition coordinator in Egypt described the report as a government report because it had been prepared by the Ministry of Housing, Utilities and Urban Communities, and a National Habitat Committee had not been formed. One of the shortcomings of the National Report however, was that the ISDF did not participate in its preparation, although the report contains a section on informal settlements. Among other preparations arranged by the Egyptian state was establishing the first “Egypt Urban Forum” (EUF) in 2015, through the collaboration between the Ministry of Housing and the Ministry of Urban Renewal and Informal Settlements – before the latter was dismantled – and the United Nations Human Settlements Programme, with the aim “to strengthen the existing urban institutional landscape at the national level and pave the way towards a greater integration of Egypt on the global urban development scene” (EUF, 2015). Several civil society organizations were invited to the forum to present their activities, projects, and the urban challenges that they face. We can say that the participation of civil society was present, but what is not clear is how the existing urban institutional landscape at the national level was strengthened. The second part of the goal of the conference was mainly part of the Egyptian preparations for Habitat III. First of all, the forum website was launched in English only (Borham, 2015), which made one researcher (urban researcher) wonder For Whom is the Conference (Borham, 2015)? But Arabic translation of the contents was added to the site later on. The Conference Report was in English also, and soon the reason became clear because the report has been sent to Quito and work is currently underway on the Arabic version. It seems that the purpose of these preparations was the crystallization of the Egyptian urban challenges so that they would be taken into consideration, with the other participating countries, to develop an international urban agenda. But we have concerns about the presentation of the urban challenges in the National Report, on the part of the government and the civil society. As it seems that the government, when formulating the National Report, lacked the understanding of the various dimensions involved in the challenges mentioned, moreover it still uses the language of numbers only. When informal settlements were mentioned, it was pointed out that the lack of a precise definition of those areas is one of the challenges that hinder their development. Yet despite this, the term “slums” and the term “informal settlements” were both used interchangeably, without clarifying the difference between the meanings of the two terms, not to mention the negative connotation of the term “slums”.

At first glance it seems that the government understands the problem of the lack of a specific definition, which is an issue that we have to bypass and deal with the actual problems of each area separately. But the government then defined such areas quite generally, using terms that refer only to the physical problems (housing, services, and infrastructure) of those areas and to highlight their negative aspects. It is important to realize that providing definitions and terminologies should not entail that the specific problems of each area become glossed-over or vague. Each area should be dealt with as one that has specific characteristics and qualities, and should be described as such, regardless of the general terminology applied to it.

Also, with respect to housing challenges, the report mentioned that the State in its quest towards providing adequate housing for all builds social housing projects and provides housing units for low and middle income.12 However, residential units are not synonymous with the concept of adequate housing (Habitat International Coalition – Housing and Land Rights Network, 2016), the components of which were defined and agreed upon in the Right to Adequate Housing report issued by the United Nations.

With respect to the civil society, it seems that the government had not invited it to the preparations for Egypt’s participation in Habitat III. In return, the civil society in Egypt did not provide any obvious contributions in the drafting of urban challenges in Egypt, similar to the parallel reports submitted by the international civil society, such as the (The City we Need), and the statement of the Brazilian civil society about the New Urban Agenda which was translated by TADAMUN initiative. However, one cannot overlook the initiative of ten organizations from Egyptian civil society to draft a report parallel to the National Report, to assess Egyptian Urbanism in relation to the commitments of Istanbul Agenda in line with the directions of the United Nations in drafting reports. Indeed among those organizations that met were TADAMUN, 10 Tooba, and Habitat International Coalition. In this meeting it was agreed that the parallel report should contain the same provisions as the National Report. Those provisions were divided among the organizations, but the initiative did not succeed because of the complexities of the evaluation, which required human and material resources that were not available to civil society (Habitat International Coalition – Housing and Land Rights Network, 2016).

It is also worth noting the “Project Supporting Habitat III: The Implementation of the New Urban Agenda in Egypt”, which was launched by the GIZ in collaboration with the Ministry of Housing to promote the participation of Egypt in Habitat III. The theory of the project can be summarized in the fact that the absence of coordination between development partners disrupts the building of a better urban environment. The project believes that understanding the different roles of partners could lead to more effective urban development. Therefore, the project works to gather many of the development partners from civil society, especially academics, practitioners and urban researchers to be part of this project, in order to chart the road map for the implementation of the recommendations of the New Urban Agenda in Egypt. The project views the “New Urban Agenda” as an opportunity to create an urban dialogue, which consequently will enable many of the development partners to engage and support the government in implementing the recommendations of the agenda at the national and local levels. However, we hope that the project ends with the actual implementation of the New Urban Agenda and not just with the charting of a road map.

Egypt after Quito

Quito is considered the starting point of the “New Urban Agenda”, the final draft of which was developed during the period of preparations. Before we contemplate our aspirations beyond Quito, we must pause a while to determine the nature of that Agenda. We see it as a universal document, ratified by member States, through which the United Nations aims to gain the political commitment of the participating countries towards urban issues, and in return these countries prove their presence in the international scene of development, thus gaining some kind of legitimacy. Therefore, the criticisms directed at it that it is impractical and utopian (Beattie 2014, Sandbu 2015) are refuted. That is why we believe that we should put the agenda in its correct context so that we can visualize our expectations realistically. This agenda, for example, will not bring back the informal settlements that were demolished and their residents forcibly evicted n Brazil, or in any other city, in order to build the facilities for the last Olympic Games, (Phillips, 2016).

The New Urban Agenda also includes general principles that few would disagree with. It is criticized because it lacks rural development, which is considered a regressive step in the direction of the comprehensive development of human settlements. The significance here is that probably the reason behind curtailing the agenda is to reduce the political commitment, which is what the countries participating in Habitat wanted.

On the other hand, the agenda is published every twenty years. Egyptian urban challenges have become more complex over time, because they were dealt with ineffectively. Twenty years ago, the informal sector was not controlling the Egyptian economy – as well as many developing countries – to the same extent. Hence the dimensions of these challenges have changed, as well as the institutional factors constituting them, among which are the policies and legislation. We cannot ascertain the impact of the Habitat Agenda or the New Urban Agenda on Egyptian urbanity, as the influential players have become so numerous now as to exceed the breadth of our knowledge not to mention the non-linearity of expectations. But we can say that the issuance of the agenda every twenty years makes it essential that the United Nations periodically reviews and evaluates the extent of commitment of the countries in implementing the agenda, as this will be a kind of continuous pressure to ensure the commitment to the principles of the agenda; in fact, the agenda recommended in paragraph 166 that the member States and the concerned organizations should submit, voluntarily, periodical reports on the implementation of the New Urban Agenda every four years. Otherwise, the agenda will only be an evaluation of the preceding twenty years. On the other hand, civil society must monitor their respective governments’ implementation of the agenda as a third party that can influence the future negotiations, because the implementation of the agenda is primarily dependent on the political commitment of the countries. Without the follow-up on that commitment by various parties, the agenda can become mere ink on paper. It is clear that these agendas, for example, are incapable of compelling the Egyptian government, or any of the governments, to provide adequate housing.

Works Cited

Borhām, A. (2015). Al-Mo’tamar liman? [The conference, for who?]. Al-Shurūk Newspaper. Retrieved on October 2, 2016.

Egypt News. (2007). Iftitāḥ Wiḥdat Taṭwīr al-‘Ashwāiyyāt bi-moḥāfazit al-Qāhira [Opening of the Urban Upgrading Unit in Cairo Governorate].

Habitat International Coalition – Housing and Land Rights Network. (2016). Egypt’s Urban Challenges in Light of Habitat III. Land Times. Retrieve on October 2, 2016.

Habitat International Coalition – Housing and Land Rights Network. (2016). Social Function. Land Times. Retrieved on October 2, 2016.

Habitat International Coalition – Housing and Land Rights Network. (2016). Egyptian NGOs, Thinking outside the Habitat III Box. Land Times. Retrieved on October 5, 2016.

Egyptian Urban Forum. (2015). ‘An al-Muntada al-Misrī al-Ḥadarī [About the Egyptian Urban Forum]. Retrieved on October 3, 2016

Fārūk, A. (2010). Ḥarīk Hā’il yaltahim thilth Sūq al-Tūnisī bil Qāhira [Huge Fire ravaged Sūq al-Tūnisī in Cairo]. Al-Ahrām Daily

TADAMUN. (2015). Coming Up Short: Egyptian Government Approaches to Informal Areas. Retrieved on: Ocober 9, 2016. .

Phillips, D. (2016). Rio 2016: Favela residents being evicted days ahead of Olympics. The Independent.

Ḥussein, D. (2015). My City, whose responsibility? Mada Masr. Retrieved on October 9, 2016.

Informal Settlements Development Fund. (2008).`An al-Ṣundūq [About the Fund].

Culpin C. and Partners. (1983). Urban projects manual. (F. Davidson, & G. Payne, Eds.) Liverpool: Liverpool university press in association with Fairstead press.

Nada, M. (2015). Galsit al-maw`il al-Thālith fi al-Muntada al-Ḥadarī al-Misrī [Habitat III session at the Egyptian Urban Forum]. The Egyptian Urban Forum. Cairo.

Khalifa, M. A. (2015). Evolution of informal settlements upgrading strategies in Egypt: from negligence to participatory development. Ain Shams Engineering Journal, 1-9.

Mohyī, M. (2015). The Maspero Triangle: Necessary Demolition or Forced Eviction? Mada Masr. Retrieved on October 2, 2016.

Amnesty International. (2009). Burried Alive: Trapped by Poverty and Neglect in Cairo’s Informal Settlements. Amnesty International. London.

UN-Habitat. (1976). The UN conference on Human Settlements (Habitat I). The Vancouver Declaration on Human Settlements (p. 54). United Nations. Vancouver.

UN-Habitat. (1996). United Nations Conference on Human Settlements (Habitat II). The Habitat Agenda. United Nations. Istanbul.

UN-Habitat. (2012). History, Mandate and Role in the UN System. Retrieved on October 2, 2016.

Egyptian Ministry of Exterior. (2016). Irshadāt al-Safar: al:Ikwador [Travel Guidance: Ecuador].

Ministry of Housing, Utilities and Urban Communities. (2016). Arab Republic of Egypt National Report

1. To find out more about the history of the two conferences, please refer to the first article in the series of articles A User’s Guide to the Third United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Development (Habitat III).

2. (Group 77 and China) is the largest grouping of developing countries in the United Nations, through which a platform is provided for those countries to formulate and promote their ideas, their common economic interests, and reinforce their positions and their negotiating capacity on all economic levels within the United Nations system, as well as strengthening the international cooperation among group members. The Group had been established on the fifteenth of June in 1964.

3. 3Article 63: “All forms and types of arbitrary forced displacement of citizens shall be prohibited and shall be a crime that does not lapse by prescription.” (Egyptian Constitution 2014)

Article 68: “Information, data, statistics and official documents are the property of the People and the disclosure thereof from their various sources is a right guaranteed by the State for all citizens. The State is committed to provide and make them available to citizens in a transparent manner. The Law shall regulate the rules for obtaining them and terms for their availability and confidentiality; the rules for their deposit and storage; and the rules for and filing complaints against the refusal to provide them. The Law shall also impose penalties for withholding information or deliberately providing wrong information. The State institutions shall deposit official documents with the National Library and Archives once they are no longer in use. The State institutions shall also protect, and secure such documents against loss or damage, as well as restoring and digitizing them using all modern means and instruments according to the Law.” (Egyptian Constitution 2014)

Article 78: “The State shall ensure the citizens’ right to adequate, safe and healthy housing in a manner which preserves human dignity and achieves social justice. The State shall devise a national housing plan which upholds the environmental particularity and ensures the contribution of personal and collaborative initiatives in its implementation. The State shall also regulate the use of State lands and provide them with basic utilities within the framework of comprehensive urban planning which serves cities and villages and a population distribution strategy. This is to be applied in a manner serving the public interest, improving the quality of life for citizens and safeguards the rights of future generations. The State shall also devise a comprehensive national plan to address the problem of unplanned slums, which includes re-planning, provision of infrastructure and utilities, and improvement of the quality of life and public health. In addition, the State shall guarantee the provision of resources necessary for implementing such plan within a specified period of time.” (Egyptian Constitution 2014)

4.For more information about spatial inequality in the distribution of resources, please refer to the TADAMUN Initiative article about Spatial Inequality in Cairo.

5. For more information about the analysis of the State policy in building new cities, the effect on Egyptian urbanity and the worsening of spatial injustice, please refer to the TADAMUN Initiative article about New Cities.

6. To find out more about community participation in development between law and practice, please refer to the TADAMUN Initiative article about Public Hearings.

7. The two TADAMUN Initiative articles: Why did the Revolution Stop at the Municipal Level? and Who Pays for Local Administration?, dealt in detail with the role of municipalities in development within the framework of the Egyptian central government.

8. (Site and Service) is a method and approach to urban development that depends on partnership between government and the citizens. The role of the government is limited to subdividing the land, selling it to the citizens, and providing the plots of land with the basic services and infrastructure through the proceeds of the selling, the citizens will assume the costs of building their homes.

9. (In-situ development) is another method of urban development. It aims to gradually improve and develop the existing buildings and infrastructure in the informal settlement until it reaches an acceptable level, while avoiding the destruction of the urban fabric, or the displacement of the citizens to another area or to another location in the same region (TADAMUN 2015).

10. Cairo Urban Initiatives Platform is a website that includes all initiatives that is related to Egyptian urbanity in any way. http://www.cuipcairo.org/

11. TADAMUN Initiative was not able to obtain a copy of the decree, and thus we do not know who the members of that committee are

12. The shadow Ministry of Housing presented the Guide for Social Justice and Urbanity in 2013, where the housing market in Egypt was analyzed, also how the social housing does not reach the targeted income groups.

Comments