A User’s Guide to the Sustainable Development Goals

Egypt’s National Assessment of Progress Towards Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a new set of goals, targets, and indicators published by the United Nations to define global development priorities for the 2015 – 2030 period. The SDGs take the place of and build upon the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which set global development priorities for the 2000 – 2015 period. Unlike the preceding MDGs, which were defined by a small group of experts, the SDGs are the result of the largest consultation process in UN history (Ford 2015). Following the Rio+20 UN Conference on Sustainable Development in 2012, the UN created an open working group with representatives from 70 countries to develop a draft agenda. The UN also launched a series of ‘global conversations’—11 thematic and 83 national consultations with governments, civil society organizations, activists, academics, the private sector, and others; and door-to-door surveys—and an online ‘My World’ survey, which asked people to identify what they would like to see in the goals. The open working group presented a draft agenda incorporating their priorities and the findings of the ‘global conversations’ and ‘My World’ survey to the UN in late 2014, and this agenda formed the basis for intergovernmental negotiations from January to August 2015. In September 2015, after seven months of negotiations, the UN General Assembly unanimously adopted Resolution 70/1 “Transforming Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development,” which lays out its 17 goals and 169 targets, or sub-goals.

The Sustainable Development Goals. (Source: United Nations, 2015).

The SDGs are aspirational, broad, and are quite vague on accountability and implementation. Still, the SDGs create a space for public policy activists, urbanists and others working on urban issues to weigh in on national development plans and urge their governments to enact policies that favor sustainability and the rights of disenfranchised groups. The ambitious and daunting goal that leads off the UN document, “End Poverty in All its Forms Everywhere” offers a clear opportunity for rights advocates across the world.

What is New?

The SDGs are essentially a second iteration of the MDGs, but with major differences in process and scope. The deliberations to define the SDGs, as described above, were significantly more inclusive and participatory than the development of the MDGs. Regarding scope, the SDGs contain more than twice as many goals as the preceding MDGs and address a much wider range of issue areas, from gender equality to climate change. The MDGs (Figure 2) set goals aimed at making incremental, quantifiable improvements—i.e. halving the proportion of people whose income is less than $1 a day—while the SDGs (Figure 1) aim to reach a statistical zero on most targets, such as poverty, hunger, and preventable child deaths. This means that governments cannot focus on making aggregate improvements at the national level: they must make improvements among the poorest and hardest to reach communities. The SDGs devote more attention to uniquely urban issues than the MDGs did and include, for the first time, a stand-alone cities goal: Goal 11, to “make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable.” The SDGs also contain more detailed environmental objectives than the MDGs.

The Millennium Development Goals. (Source: United Nations Development Program, 2000).

Consensus or Jousting Arena?

While the 2030 Agenda has attracted praise for its more inclusive design process, skeptics have questioned the need to incorporate so many objectives in one document and wondered about the conflicts and hurdles this may pose to its implementation (Beattie, 2014; Sandbu, 2015). Some argue that the all-inclusive process simply led to a set of goals representing too many interests within the development industry (Beattie 2014). Too broad a scope may have compromised the feasibility of the document and diluted its focus.1 How can countries be expected to make meaningful improvements on so many fronts? How will countries prioritize these goals? Is propagating a single set of targets to drive government policy across the entire world worth doing at all (Beattie, 2014; Sandbu, 2015)?

The Post-2015 Agenda’s sheer bulk, its complexity, and the multi-faceted interaction among its elements may certainly confound anyone examining the SDGs’ 17 goals and 169 targets. More importantly, the SDGs are exceedingly vague when it comes to implementation. The document provides little in the way of mechanisms for action, responsibilities of specific actors, accountability, or enforcement measures.

Admittedly, this weakness is inherent of the very scope of the endeavor. It is inconceivable for any organization, or a consortium of official and non-official groups in this case, to be specific when attempting to create a truly global agenda. But the very scope of the endeavor also endows it with undeniable authority. The SDGs derive their power, in part, from their universal support: all 193 countries in the UN General Assembly signed on to the 2030 Agenda, making a formal commitment to achieve the ambitious goals over the next fifteen years. The document would not have been so universally adopted if it required governments to cede too much control, and, while some countries would still have signed on, many countries would have refused. Since it is a non-binding agenda—states signed on via a UN General Assembly resolution and General Assembly resolutions do not create legal obligations under the UN Charter—the 2030 agenda suggests that the SDGs are to be implemented through a “global partnership,” featuring not only governments but also civil society and the private sector.

The scale and ambition of the new Agenda requires a revitalized Global Partnership to ensure its implementation. We fully commit to this. This Partnership will work in a spirit of global solidarity, in particular solidarity with the poorest and with people in vulnerable situations. It will facilitate an intensive global engagement in support of implementation of all the Goals and targets, bringing together Governments, the private sector, civil society, the United Nations system and other actors and mobilizing all available resources (United Nations 2014, 10).

It is not clear what the UN has in mind when it suggests a “Revitalized Global Partnership” for implementation. What it seems to imply is that if everyone works hard together, including governments and civil society, businesses and workers, the employed and the disenfranchised, the planet will somehow be able to achieve peace, advance welfare, and protect the environment. If this is so, then the whole document is left wide open for criticism as impractical and utopian. But the SDGs are not a plan for action, as they claim to be. They are an arena for jousting, a set of rules for bargaining, a moral ground for pressuring, a floodlight on trouble, and a soapbox for public policy advocates. They erect the stadium, set up the tent, put up the signs, and invite everyone to the match.

There is much in the SDGs that public policy advocates can use in pursuit of their objectives, probably intentionally so, since a diverse set of actors drafted the final document. Far from being a new international treaty, the 2030 Agenda is an “inspirational” document, albeit one that advocates collaborative implementation and detailed monitoring and assessment. Although technically nonbinding, the SDGs can go a long way to create the practice, habit, and process of collaboration required for such an ambitious mission.

Global Partnership

In the UN Preamble for the SDGs, the authors make it clear that civil society groups have a role to play in both the implementation and the monitoring of activities related to the new global agenda. When governments develop SDG-focused national action plans, (and almost all governments do), advocacy groups will take note and track those plans and associated government policies and actions. The UN’s hopes for a “Global Partnership” can only work if environmentalists, community groups, philanthropic organizations, labor groups, and advocates for responsible urbanism, such as TADAMUN, join the agenda and work to implement it. The UN has thus given public policy advocates a forum through which to speak with a clear and legitimate voice. The idea of a “Global Partnership” also makes a statement about governance. By telling governments that they are partners with civil society, the UN may not be simply painting a rosy picture of collaboration and harmony but proposing a new political climate – although the authors did their best to downplay this point.

A Chance for Urban Advocacy

For organizations and advocates doing work to promote the welfare of vulnerable groups and the sustainability of cities, the SDGs have much to offer. Goal 11—to make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable—is solely dedicated to the future of cities and their inhabitants. Its targets are particularly relevant to the work that TADAMUN and other similar initiatives are already undertaking, and emphasize the importance of the Right to the City, and the Right to Adequate Housing.

Target 11.1, for example, explicitly makes the right to adequate housing the focus of housing initiatives. It defends the rights of those living in informal settlements to upgrade their homes and to receive basic services, rather than to have their homes demolished and be forcibly relocated elsewhere:

By 2030, ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services and upgrade slums (SDG Target 11.1).

Beyond Goal 11, throughout the other SDGs there are targets that are directly related to the most pressing development imperatives concerning urbanists. Target 2.3, for example, is a powerful statement for defending people’s rights to land and productive resources:

By 2030, double the agricultural productivity and incomes of small-scale food producers, in particular women, indigenous peoples, family farmers, pastoralists and fishers, including through secure and equal access to land, other productive resources and inputs, knowledge, financial services, markets and opportunities for value addition and non-farm employment SDG (Target 2.3).

The document also builds a case for national and international investment in anti-poverty programs and disaster aversion mechanisms.

By 2030, build the resilience of the poor and those in vulnerable situations and reduce their exposure and vulnerability to climate-related extreme events and other economic, social and environmental shocks and disasters (SDG Target 1.5).

Target 1.4 articulates the right of the poor to basic services and accessible finance.

By 2030, ensure that all men and women, in particular the poor and the vulnerable, have equal rights to economic resources, as well as access to basic services, ownership and control over land and other forms of property, inheritance, natural resources, appropriate new technology and financial services, including microfinance (SDG Target 1.4).

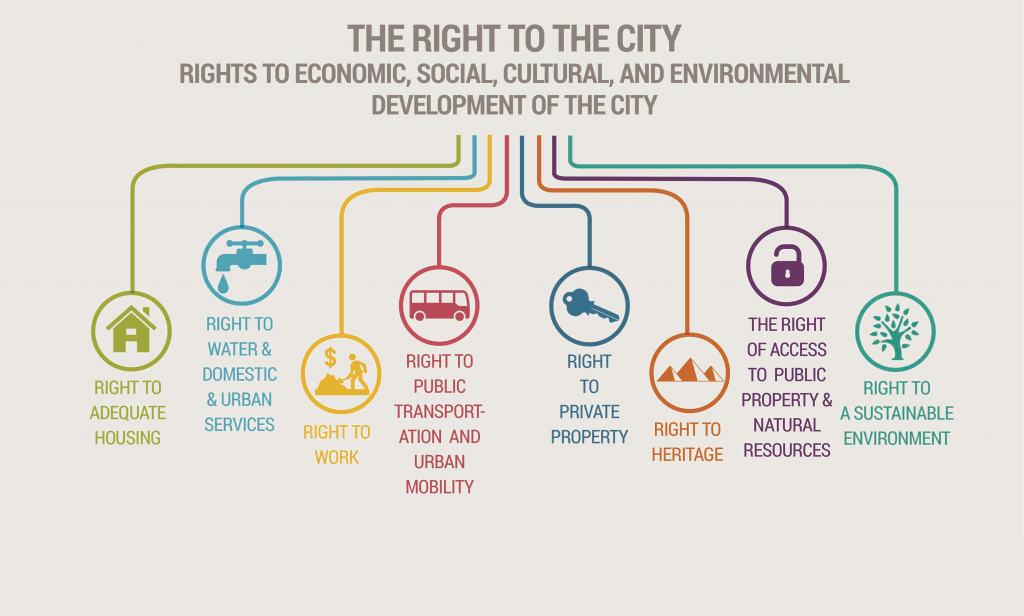

SDGs and the Right to the City

As mentioned above, throughout the SDGs there is a clear endorsement of some elements of the Right to the City. Goal 11 advocates the right of all city dwellers to live in decent conditions and to shape the form and future of their environment. Just like the rest of the SDGs, the Right to the City is a multi-faceted concept rooted in community participation and in the belief that people in elected or non-elected office should base their actions on the needs of all members of society, and not the powerful ones alone. Article 23 of the Constitution of Ecuador (2008) captures the spirit of the Right to the City:

Persons have the right to fully enjoy the city and its public spaces, on the basis of principles of sustainability, social justice, respect for different urban cultures and a balance between the urban and rural sectors.

Exercising the right to the city is based on the democratic management of the city, with respect to the social and environmental function of property and the city and with the full exercise of citizenship (Constitution of Ecuador 2008).

In defending the Right to the City, one not only promotes a future of equity and sustainability, but also lays the groundwork for a new relationship among government, the private sector, and civil society. If this idea gains more traction, the 2030 Agenda may help alter the current modes of authority and production, establishing new methods and habits of reasoning, debate, and action. It is perhaps too much to hope for many countries to follow in the footsteps of Brazil, which in June 2001 integrated several of the basic concepts of the Right to the City into Federal law.2 But if more nations were to follow Brazil, or if more cities were to adopt executive measures bolstering such a right, a momentum could be built for advocates elsewhere to demand similar action. When Henri Lefebvre, a French Marxist sociologist started advocating the Right to the City in 1968, few could have foretold that his ideas would not only drift into the mainstream, but into UN thinking on urban matters (Lamarca 2009). At the very least, the SDGs are a powerful international endorsement of basic tenets of the Right to the City, and provide a critical platform on which advocates may stand when defending this right.

Conclusion

The true merit of the SDGs is not that they tell us exhaustively what we need to get done over the next fifteen years, but that they bring about a paradigm shift by imagining new and perhaps untested ways of doing things. The energy they bring to the debate on human development and priorities for the coming development era is considerable. All 193 member states have endorsed the SDGs at least once (the UN General Assembly unanimously adopted Resolution 70/1), and this nearly universal endorsement imbues the goals with an authority upon which nations and citizens alike can build a plan to achieve at least some of the SDG’s grand promise. In writing this document, the UN knew that they could only achieve relative commitments from governments, not absolute promises. In doing so, the document’s authors left a void in the middle, a space between reality and aspiration to be filled. And it is conceivable that they expected advocates to step in and fill the void. As governments begin and continue the process of articulating national development plans for the next 5, 10, and 15 years, the SDGs will provide a powerful set of priorities, which advocates may make use of to hold their governments accountable.

The Egyptian government, for example, has launched Egypt Vision 2030, and articulated a number of sustainable development plans addressing the SDGs specifically, such as this May 2015 document published by the Ministry of Planning, Monitoring, and Administrative Reform. Although Egypt Vision 2030 pays lip service to the SDGs, it is unlikely with the track record of the Egyptian government’s urban development policies that the essence and ultimate purpose of the SDGs – increasing social justice – are highly prioritized. For example, the government’s urban development policies continue to funnel public investments to the unaffordable, new cities that are sparsely inhabited, with little support left for the debilitating urban cores that house the vast majority of the population. However, despite its shortcomings – which will be further discussed in future TADAMUN articles – the Egyptian government’s sustainable development agenda gives activists and public policy advocates a clearer understanding of the government’s development vision, which they can compare to the SDGs the government committed to in front of the international community.

Though the agenda is non-binding, the SDGs carry the UN’s moral power. The tangible effects of the new agenda will emerge through practice, through the formation of new habits and memories, and through the aspirational work of all those involved. Over the years, the UN has been active in peace keeping, humanitarian assistance, environmental monitoring, and arms control with laudable but incomplete success. Now it is launching an attempt to shape the next generation of global development that clearly exceeds its authority, but perhaps not its prestige; that clearly exceeds its resources, but not its insight; that clearly exceeds its power of implementation, but – hopefully – not its power to inspire.

Will it work out? No one knows. But the agenda has been set, the arena specified, and the players have been named.

Works Cited

Beattie, Alan. 2014. “New UN Development Goals, Still Missing the Point.” Financial Times. 21 August. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

Ford, Liz. 2015. “Sustainable Development Goals: All You Need to Know.” The Guardian. 19 January. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

Lamarca, Melissa García. 2009. “The Right to the City: Reflections on Theory and Practice.” polisblog.org. November. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

Sandbu, Martin. 2015. “Critics Question Success of UN’s Millennium Development Goals.” Financial Times. 15 September. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

United Nations. 2015. “Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.” Sustainabledevelopment.un.org. Retrieved 2 April, 2016.

Footnotes

1. Critics tend to characterize the UN global development agendas, including the recent one, as impractical and utopian. See for example Alan Beattie (2014) and Martin Sandbu (2015).

2.Brazil’s 2001 City Statute regulates the chapters on urban policy in Brazil’s 1988 constitution and defines general guidelines by which federal, state, and local governments must abide to ensure democratic city management and the recognition of the social function of urban property and the city. It provides an extensive set of mechanisms by which governments may protect urban residents’ right to the city, such as progressive property and land taxes; compulsory parceling and building; and expropriation/sanction. It also provides for the establishment of Special Social Interest Zones (ZEIS). For more information on the City Statute, see this Cities Alliance commentary.

Comments